Abstract

Mosaic ceramics are not limited to use solely as building materials, they also possess artistic value. Artists can create images by arranging and combining mosaic ceramics, resulting in a perfect fusion of large-scale public art for external walls and ceramic materials. However, the current approach for artists to create mosaic ceramic exterior wall art images involves manual laying and assembling of individual mosaic ceramics. This manual process suffers from issues such as low efficiency, eye fatigue, selection errors, and the risk of high-altitude operations. These challenges significantly impact the quality and efficiency of creating mosaic ceramic exterior wall art image images. To address these problems, this paper proposes an automatic mosaic ceramic art image stitching method based on subpixel edge fitting positioning and collaborative operation of multiple robotic arms. Additionally, a new U + I type conveying method is designed for efficient and space-saving transportation of mosaic ceramics. Experimental results demonstrate a high success rate of recognition, absorption, and placement of multi-color mosaic ceramics using this method reaching 95.45%, with a positioning error within 0.5 mm. The method can also adapt to varying levels of light intensity or noise interference. This approach effectively enhances the quality and efficiency of creating mosaic ceramic exterior wall art images and promotes the development of mosaic ceramic exterior wall public art creation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mosaic ceramic exterior wall art images are created by arranging and combining mosaic ceramics into art image works1. Throughout history, artists have produced numerous world-famous mosaic ceramic art pieces in this form, such as the Mona Lisa of Galilee and the Nile Family in the 4-th century AD Rome2. Traditional exterior wall paintings are prone to aging and can lose their artistic value over time. In contrast, mosaic ceramic exterior wall art images, as fundamental elements, can maintain their excellent artistic effect for many years. This durability is primarily due to the insulation3, heat resistance4 and other properties inherent in ceramic materials, enabling them to withstand external natural conditions such as long-term sunlight and rain immersion5,6. Artists widely appreciate these beautiful, classic, and long-lasting mosaic ceramic art images as an ideal fusion of art and ceramics. However, the traditional method for creating mosaic ceramic art images involves manually arranging and laying individual mosaic ceramics on the exterior walls of buildings, commonly known as the “direct method”. This technique requires artists to possess highly stable skills, making it difficult to consistently ensure the quality of the final artworks7,8,9. Additionally, the “direct method” is time-consuming and often entails working at elevated heights, which poses safety risks. Moreover, mosaic ceramics come in various colors, and human eyes are prone to making incorrect choices when observing them, further affecting the efficiency of art creation10,11. In addition to the “direct method”, artists have proposed the “indirect method”, which involves pre-laying mosaic ceramics into small units and subsequently assembling and placing these units on the exterior wall to achieve large-scale artistic creations12. However, both the direct and indirect methods rely on manual operation13,14, making them labor-intensive and subject to issues such as fatigue, inaccurate judgment, and incorrect operations15,16,17. These factors ultimately impact the efficiency and quality of artists’ creations18,19. An effective solution to address these challenges is to employ robotic arms to pre-assemble and embed mosaic ceramics into modular images, which are then laid on the exterior wall. This process takes place on a flat surface, ensuring safety and efficiency compared to working at high altitudes. Therefore, achieving automation, precision, and rapid tiling of mosaic ceramic art image creation is key to improving the efficiency and quality of artists’ work.

To achieve automation, precision, and rapid tiling of mosaic ceramic art patterns, researchers have conducted extensive related work. Kaya et al.20 proposed an automatic generation method for square ceramic tile images used in tile tiling. This method determines tile direction and supports tile feature detection by generating images without overlapping tiles, facilitating dataset extraction or embedding. While it effectively maintains image integrity, it does not achieve automatic tiling of mosaic ceramic images. Hung et al.21 developed a robot recognition system. This system achieved automatic image stitching and successfully applied it to the Six degrees of freedom Ultimate Puma 500 industrial robot for glass mosaic splicing in any plane. Although the paving speed and flexibility were improved, motion stability and accuracy remained insufficient. Oral et al.22 proposed an algorithm for mosaic tiling-based splicing algorithm and a robot control algorithm. They also designed and manufactured a four-degree-of-freedom Cartesian robot for mosaic ceramics, that supports reading relevant data including dxf format and calculating the position of image components. The robot can be driven by a motor and pulley on a flat surface, with a cylinder in the Z-axis direction guiding the robotic arm’s placement of mosaic ceramic images. However, this method has low motion accuracy and a low degree of automation, failing to meet the automation and precision placement requirements of mosaic ceramics. Additionally, Museros et al.23 proposed a two-dimensional object shape recognition theory that calculates the similarity between shapes and colors of different image objects to achieve intelligent and automated placement. While this method can identify various regular or irregular patterns, it requires a large training dataset, leading to long preparation times and high technical costs. To address the time and cost challenges of tiling, Han et al.24 proposed a method for accelerating map generation based on map position, similar to human sorting methods. This approach locates image blocks based on image edges and adjacent block shapes, determines the shape based on the position of each tile, and achieves high-speed mosaic ceramic tiling while preserving the artistic creation effect of mosaic ceramics25,26. However, this method exhibits low computational efficiency when tiling high-resolution mosaic ceramic art images and only tile one color of mosaic ceramic at a time, making it challenging to meet the requirements and in need of further improvement.

Although the methods have essentially addressed the issue of low efficiency in manually laying of mosaic ceramics, they all rely on traditional mechanical equipment to complete the tiling process. However, the automation and system integration levels of this tiling equipment is inadequate. Moreover, these methods and equipment exhibit low recognition and positioning accuracy when laying mosaic ceramics, failing to meet the requirements of automation, precision, and fast laying in mosaic ceramic art image creation. Particularly, the characteristics of having multiple color categories, small volume, high similarity, and smooth, reflective surfaces pose challenges that existing methods cannot effectively overcome.

Consequently, the need for an efficient method to tile multi-color mosaic ceramics has become imperative. Thus, this article proposes an automatic tiling method for multi-color mosaic ceramic art images based on subpixel edge fitting positioning and collaborative operation of multiple robotic arms. Additionally, a tiling system platform is designed to enable the simultaneous control of multiple robotic arms for collaborative operations and real-time detection of the laying effect. This advancement significantly enhances the efficiency and accuracy of laying mosaic ceramic art images, meeting the high-quality creative demands of artists for mosaic ceramic exterior wall art images.

Mosaic ceramic tiling system

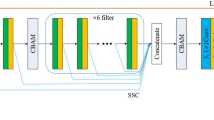

The mosaic ceramic tiling system described in this paper comprises multiple Link Hou robotic arms, U + I conveyor belts, encoders, industrial CCD cameras, coaxial light sources, gantry frames, flange connectors, suction nozzles, tiling boards, and other components, as shown in Fig. 1. The tiling process for mosaic ceramics is accomplished through the collaborative operation of these robotic arms. The I-type conveyor belt transports multi-color mosaic ceramic raw materials, while the U-type conveyor belt carries the tiling boards. The collaborative operation of multiple robotic arms significantly enhances tiling efficiency. Each robotic arm is equipped an encoder to identify, locate, and grasp the mosaic ceramics from the U-shaped conveyor belt. The robotic arm accurately places the mosaic ceramics in the corresponding grid on the tiling board according to specific requirements. The image acquisition equipment employs high-resolution, high-definition, and high-precision MV-E series industrial cameras. In addition to the multiple robotic arms, this system also incorporates an innovative U + I conveyor belt structure composed of U-shaped and linear I-shaped components. This U + I conveyor belt structure not only saves space but also facilitates the collaborative operation of multiple robotic arms.

In the process of mosaic ceramic paving, several steps are implemented to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of placing multi-color mosaic ceramics. First, each mechanical arm is programmed to recognize and grasp only one color of mosaic ceramic, ensuring clear operation of each arm. Second, the tool coordinate system of the manipulator is calibrated to align with the user coordinate system. As the suction cup in the tiling system is coaxial with the six axes of the manipulator, aligning the center of the suction cup with the six-axis external reference point during installation ensures proper alignment. It is essential to maintain consistency in the origin of the tool coordinate system and calibrate the X reference point, aligning the X positive direction with the movement direction of the conveyor belt. Finally, for improved robustness of the manipulator, the linear I-type conveyor belt is divided into a photographing area and multiple capture areas by combining the industrial CCD camera and encoder. The schematic diagram illustrating the principle of mosaic ceramic tracking on the conveyor belt is shown in Fig. 2.

In this system, the encoder is used to calibrate the pulse quantity. The calibration process involves the following steps: first, the encoder ensures the stability of conveyor belt transmission. The calibration line is then positioned at point P1 while in a static state. After selecting the calibrated user coordinate system, the manipulator’s end is moved to point P1, and its position is recorded. Subsequently, the conveyor belt is started, moving the calibration line to point P2. The manipulator is moved again, and the position is recorded. The pulse equivalent of the encoder is obtained by calculating the recorded point information twice, completing the calibration of the grasp region. The encoder provides real-time pulse positions for both points, P1 in the recognition area and P2 in the grasping area. When the mosaic ceramic reaches the grasping area, the conveyor belt stops running. At this point, the pulse module sends a grasping signal to the mechanical arm, determining the central point position of the mosaic ceramic and waiting for the next step. Similarly, the U-type conveyor belt operates in a manner akin to the straight I-type conveyor belt.

Mosaic ceramic visual inspection system

Figure 3 depicts the flowchart of mosaic ceramic inspection within the mosaic ceramic automatic laying system. The main detection workflow unfolds as follows. First, an industrial camera captures mosaic ceramic images in the photography area and subsequent analysis and processing are conducted on these images. The obtained images are then transformed into the Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) color space. The HSV color model is preferred over Red-Green-Blue (RGB) models as it can more effectively highlight the color and contour features of ceramics, facilitating the subsequent acquisition of target mosaic ceramics. Layered and subpixel edge detection methods are employed to identify the color and position of mosaic ceramic pieces, generating a dataset. The position recognition process involves correcting image distortion with a calibration plate, followed by enhancing image edges using an algorithm to accurately determine the center position of the mosaic ceramic pieces. After identifying the center point of the mosaic ceramic, the position of the mosaic ceramic needs to be calibrated to obtain its contour coordinates, and the position identification of the mosaic ceramic is realized through point-to-point pixel transformation. Finally, the point position information in the dataset is transmitted to the robotic arm. Finally, the point information in the dataset is transmitted to the robotic arm.

Composition of the visual system

Figure 4 illustrates the working principal diagram of the machine vision system, consisting of three parts: image acquisition, image transmission, and image processing. In this system, multi-color mosaic ceramics arrive at the designated area from the conveyor belt. Initially, the illumination intensity of the LED coaxial light source is adjusted, and images of mosaic ceramics are captured using a CCD camera. The image containing the target mosaic ceramic in then transferred to the computer for segmentation, recognition, and position calibration processing. Finally, a dataset containing ceramic parameter information is generated and transmitted to the robotic arm, which operates based on the provided target parameter information.

Preprocessing of mosaic ceramic images

In the process of acquiring mosaic ceramic images, noise may arise due to factors such as unusual equipment vibration, changes in environmental lighting, and imperfections in recording equipment and transmission media. This noise often manifests as isolated pixels or blocks, introducing undesired interference in the image data. Therefore, preliminary image processing is necessary. This paper employs median filtering, a nonlinear filtering technique based on sorting theory. The principle of median filtering is to replace the value of a pixel in a digital image with the median value of its neighboring pixels, resulting in a smoother representation closer to the true image, effectively mitigating noise. This method preserves signal edges during the filtering process, enhances the clarity of image contours, and improves the accuracy of subsequent matching and positioning. The output of two-dimensional median filtering can be expressed as:

Where, f (x, y), G (x, y) are the original image and processed image, respectively, and W is a two-dimensional template, usually 3*3, 5*5 region.

To make precise distinctions between different colors of mosaic ceramics, obtaining a comprehensive dataset containing all possible mosaic ceramic colors is crucial, as it significantly impacts subsequent recognition. It is necessary to convert as many mosaic ceramics as possible from RGB to HSV color space. The purpose is to achieve color recognition in HSV color space, especially to distinguish different colors through the H channel (hue). HSV color space can effectively simulate human color perception, in which the hue is the main dimension used to distinguish colors, and the system can effectively identify different colors according to the hue range. The hue calculation equation is shown below, from which it can be seen that hue can express various colors:

Where r, g, b is the RGB coordinates of a certain color and their values are real numbers between 0 and 1. max, min are the maximum and minimum values in r, g, b respectively.

To improve the sensitivity of the system to the target color, we grayscale the image. A mask is generated to highlight specific color regions by setting pixels that match a specific color range to white and pixels that do not match to black. This makes it easier for the system to identify and extract these regions, reduces the complexity of the image, and excludes redundant and interfering information. In the process of graying RGB images, large errors will occur and Gamma correction is required. The specific algorithm is as follows:

Where Gray is the gray value of the image and R, G, B is the RGB value of the image.

This study selects over 20 mosaic ceramic images captured under diverse lighting conditions, using grayscale histograms to filter and record the grayscale value range corresponding to different types of mosaic ceramic colors. The obtained sample data are then saved. By generating a dataset based on the type and grayscale interval of the collected data, it serves as the starting point for the color recognition task of the system. Our extensive dataset obtained from a large number of images provides accurate color features for subsequent tasks, minimizing the impact of lighting variations and improving recognition accuracy.

Position calibration of mosaic ceramics

Following image preprocessing, a digital model is constructed utilizing spatial data to accurately position mosaic ceramics within the image. Concurrently, an investigation into the mathematical and logical correlations between the image and the world coordinate system is conducted, facilitating the mapping of the digital model’s location within the image to the corresponding world coordinate system. This connection involves a transition from image coordinates to world coordinates, transforming the information contained in the image into the format required by the robotic arm. In addition, the hierarchical structure and background functions of image representation can be further simplified into low-level and high-level image processing.

Initially, we obtain rough position information of mosaic ceramics through image processing algorithms, such as preprocessing and feature filtering. However, directly extracting the center coordinates may result in insufficient positional accuracy, necessitating further refinement of these images. Edge information, characterized by drastic changes in pixel grayscale, serves as an essential image feature. Extracting edges is beneficial for identifying the position of mosaic ceramics and completing their position calibration. Therefore, this paper proposes an edge detection method based on the XLD operator, using a canny filter to extract subpixel accurate edges and describe the contour in extended line descriptions (XLD). By replacing Gaussian filtering with median filtering, we preserve more edge information and extract smoother edges. In the experiment, it was observed that cluster noise caused by lighting and other factors could generate distorted XLD contours. To address this issue, we screen all XLD contours and complete the unclosed XLD contours to obtain a complete mosaic ceramic contour. During this process, some of the contours may exhibit irregularities. Using this irregular contour to obtain the center point coordinates \(\:{O}_{1}\) may result in angle and distance deviations from the true center point, which directly affects the laying accuracy of mosaic ceramics. Therefore, we leverage the shape characteristics of ceramics by matching the digital model region based on the position generation rules of all contours with each ceramic region in the image, and we find the center point \(\:{O}_{2}\) in the digital model region. This approach allows us to control the direction of the error. Then, the coordinate points in the image are obtained through weighted average calculation with the center point \(\:{O}_{1}\) following contour recognition, namely the expected suction point \(\:{O}_{3}\) of the robotic arm. This point offers higher accuracy compared to \(\:{O}_{1}\) and facilitates error analysis for further optimization. As shown in Fig. 5 (a–f), the mathematical model is generated based on the edge contour of mosaic ceramics extracted by XLD. By obtaining the center coordinates of the model area, the position coordinates of mosaic ceramics can be accurately determined. The black cross mark in Fig. 5 (a) is the coordinate point corresponding to the center position of the identified mosaic ceramics.

To establish the connection between images and world coordinates, we use MATLAB for the quick and convenient identification of the dot calibration board. Taking the dot calibration board as an example, we obtain the relevant camera parameters through calibration. This paper does not require a specific calibration board, as the parameters can be read from a file for any type of calibration board. However, to acquire camera parameter information during calibration, the calibration board needs to be imaged multiple times within the shooting range. This enables the calibration assistant to recognize the calibration board from various positions within the field of view. There are two purposes for using camera parameters: one is to generate a distortion matrix to reduce image distortion and improve image coordinate accuracy; the second is to calibrate the camera type and initial parameters set in the data model. The focal length and optical center parameter matrices \(\:{}_{r\:}{}^{l\:}R\) and \(\:{}_{t\:}{}^{l\:}T\) of the industrial camera are expressed as:

Since this paper employs the calibration board as the calculation standard, the positional relationship between the dots is known. Thus, we can select any two dots on the calibration board. We first calculate their coordinate relationships in the image, and then use operators to perform point-to-point pixel transformations, converting the image coordinate relationships into world coordinate relationships. This logical relationship is dependent on the camera’s parameter settings. When the camera is fixed, the coordinates of any point in the obtained image can be determined through this logical transformation. Similarly, the robotic arm only needs to synchronize the coordinates of any point within the camera’s range with the coordinate file of that point in the image. This allows the robotic arm to obtain the coordinates of all points and move to the target position.

Mosaic ceramic tiling experiment

Identification and positioning of targets

In this study, we conducted a tiling experiment of mosaic ceramics using multiple robotic arms for collaborative operation. This experiment involved the calibration, acquisition, and conversion of the camera coordinate system and the world coordinate system. To verify the feasibility of this approach, we selected multiple blue mosaic ceramics with similar colors, including blue light 80%, blue light 60%, blue light 40%, blue dark 50%, and blue dark 25%. The experiment is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Before the experiment, the internal parameters of the camera were checked. These parameters encompass six values (f, k, Sx, Sy, Cx, Cy), where f and k represent the focal length and radial distortion of the camera, respectively, with a calibration value of k set to 0.0. Sx and Sy denote the desired pixel’s digital logical connection, while Cx and Cy correspond to the image’s center points. The external parameters of the camera were obtained through the pose conversion method of the calibration board to complete the camera calibration. Image processing was then carried out, as shown in Fig. 6. Figure 6 (a1,a2) illustrate scattered mosaic ceramic images collected by the machine vision detection system. The visual inspection system intuitively displays the number of ceramics and the identified color data in a graphical window, as shown in Fig. 6(b1). For the experiment, blue Mosaic ceramic images with varying color depths were used as datasets, labeled as blue 1, blue 2, blue 3 and blue 4, as shown in Fig. 6 (c–f).

Finally, the image feature points were used to calibrate the target coordinate system and the world coordinate system. This calibration was achieved by determining the corresponding angles of the image feature points and the rotation translation of their corresponding points, followed by the inverse calculation of the homogeneous transformation matrix. The homogeneous transformation matrix consists of two corresponding components:

Where \(\:{}_{a\:}{}^{k\:}R\) and \(\:{}_{b\:}{}^{k\:}T\) represent the rotation matrix and translation matrix respectively.

By applying the matrix transformation to the mosaic ceramic target, the predicted results of mosaic ceramic placement can be obtained. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the left side shows the position of the target mosaic ceramic before placement in the experiment, and the right side shows the predicted position of the mosaic ceramic after placement.

The affine transformation matrix of mosaic ceramics is presented in Table 1, where H represents the rotation and translation matrix of the two groups of mosaic ceramic affine transformation results in Fig. 7(a-f).

The matrix is then converted into motion instructions that the robotic arm can comprehend. These instructions are automatically saved as files and input into the robotic arm’s program. The execution program of the robotic arm is initiated, and the success rate of grasping and placing mosaic ceramics is observed. To further evaluate the system, multiple experiments were conducted by altering the positions of the mosaic ceramics. The experimental results were then statistically analyzed using evaluation criteria such as target identification, placement success rate, location deviation, and error rate. Specifically, the location deviation (LD) and error rate (ER) of the detected mosaic ceramic are respectively expressed as:

Analysis and optimization of experimental results

Taking a 2-megapixel industrial camera as an example, the actual size of a single pixel is approximately 0.084 millimeters, which implies that the edge error is less than 0.1 mm. As the mosaic ceramic is farther away from the center of the camera, the error of the center point recognition will increase. According to the results of the mosaic ceramic tiling experiments in Table 2, the number of center point pixel offset LD (pixel), multiplied by 0.084, can be calculated that the positioning error of the end of the robotic arm are within 0.5 mm, the target recognition success rate reaches 92.9%, and the tiling success rate (PSR) is 85.7%. These results validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. The reason for analyzing the error is due to overexposure of the original image caused the reflective area of some mosaic ceramics to exceed 50%. Additionally, defects on the ceramic surface and excessive edge polishing contributed to the errors. Although overexposure leads to an increase in the reflective area of some of the mosaic ceramics and affects the dynamic range of the image, this has a limited effect on the recognition accuracy. The angle of the camera also slightly affected the extraction of ceramic edges, resulting in positioning deviations. Enhancing the pixel quality of industrial cameras can address the issue of edge extraction deviations. Furthermore, the experiment demonstrated that as long as the camera captures a complete image of the mosaic ceramics, the thickness of the ceramics has a minimal impact on ceramic edge detection, less than 10 pixels.

To examine the impact of light intensity on the recognition and grasping of target mosaic ceramics by the robotic arm, we adjusted the camera position and light brightness. Six positions within the workspace of the robotic arm were selected as experimental samples to test its grasping ability. The positional accuracy is defined as the distance between the actual position of the robotic arm end effector and the center position of the ceramic in different environments, serving as a quantitative measure of the robotic arm’s grasping performance. The average illuminance of the LED lights was adjusted to compare the effect of different brightness on the experiment for the same scene. The average illuminance equation is shown below:

Where Eav is the average illuminance, N is the individual luminaire luminous flux, ø is the number of luminaires, CU is the space utilization coefficient, and in this paper, CU is taken to be 0.4 according to the indoor reference value, MF is the maintenance factor, and in this paper, MF is taken to be 0.77, and m2 is the area.

The ambient brightness was divided into four levels (a, b, c, and d) in descending order of light intensity, as illustrated in Fig. 8 (a–d). We explored the impact of environmental brightness on the detection results of mosaic ceramics by artificially altering the brightness in the same scene. The experimental results shown in Fig. 8 (e) demonstrate that although the noise appearing in the images differs, each image detects the same grasping pose within the specified value range. The results also indicate that the relationship between the success rate of mosaic ceramic placement (PSR) and the light intensity follows an inverted U-shaped curve. It was observed that when the lighting intensity ranged between levels b and c, the laying error accuracy of mosaic ceramics was minimized, and the success rate was the highest. This suggests that the proposed method exhibits strong applicability and can adapt to the influence of uneven lighting or noise within a certain range.

After adjusting the lighting intensity to the appropriate level, the robotic arm is employed to lay five different colors of mosaic ceramics in a ratio of 1:2:2:3:3:3, forming an image of the letter “M” as illustrated in Fig. 9. To facilitate the observation of placement errors, the robotic arm follows a door type motion trajectory during the laying process. Figure 9(a–d) demonstrate the precise placement of the mosaic ceramics in the grid gaps of the paving board by the robotic arm.

In Fig. 9, the end of the robotic arm is connected to an air pump and a suction nozzle through a soft conduit. The target mosaic ceramic is then gently sucked into place using airflow. By using the suction nozzle instead of the robotic arm’s grasp mosaic ceramics, the issue of unstable gripping caused by poor contact or non-vertical force is mitigated. Moreover, the suction method only requires the center of the robotic arm’s end to be parallel to the ceramic surface, thus improving the fault tolerance during mosaic ceramic placement. Table 3 presents the experimental results data for mosaic ceramic tiling. It is evident from Table 3 that the average success rate of mosaic ceramic absorption is 96%. In the color recognition step, the method in this paper can quickly and accurately identify the tile color. Individual tile tiling errors in the experiment may be due to the accuracy of the robot or other external factors. The experiment further validates the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed automatic tiling method for mosaic ceramic art images.

After the mosaic ceramics tiling process is completed, the next step involves applying a small vibration treatment to the tiling board. This treatment ensures that any poorly placed mosaic ceramics are completely filled into the corresponding grid on the tiling board. Once the visual detection system confirms the completion of the tiling board filling, a signal is sent to the encoder. The conveyor belt is then controlled to continue its movement, transporting these tiling boards to the vibration device. The boards undergo vibration and manual inspection before being forwarded to the next stage of the process. In actual production, you can add a conveyor belt, vibration belt or through artificial vibration to improve the mosaic ceramic paving production process, and further improve the overall efficiency of mosaic ceramic tile paving.

Conclusion

To enhance the quality and efficiency of mosaic ceramic art images, this paper presents an automatic, precise, and rapid tiling method for multi-color mosaic ceramics. This innovative approach leverages the collaborative operation of multiple robotic arms to accurately place mosaic ceramic particles of various colors. Additionally, a novel U + I type conveying system is employed for the efficient transportation of ceramic pieces, significantly improving the overall workflow and precision of the tiling process. By combining subpixel edge fitting positioning with the collaborative operation of robotic arms on a U + I paving platform, this method achieves high efficiency and space-saving advantages. This approach involves pre-assembling mosaic ceramics according to the artist’s requirements, creating the desired artistic images, and subsequently applying these images to the exterior walls of large buildings. Compared to manual and semi-automatic tiling methods, this technique offers superior accuracy, speed, and automation, effectively ensuring the quality and efficiency of artists’ creations, thereby driving the advancement of mosaic ceramic art.

The experimental results further support the effectiveness of this system, with a remarkable success rate of 95.45% for mosaic ceramic placement and positioning errors within 0.5 mm. Additionally, this method exhibits remarkable adaptability to changes in light intensity. The experimental findings indicate promising industrial prospects for this approach, as it has the potential to overcome the current challenges of low efficiency and comprised quality in mosaic ceramic art image placement.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dong, G. et al. Research on automatic mosaic ceramic tiling method based on color matching. Ceram. Int. 47, 31451–31456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.021 (2021).

Neri, E., Morvan, C., Colomban, P., Guerra, M. F. & Prigent, V. Late roman and byzantine mosaic opaque glass-ceramics tesserae (5th-9th century). Ceram. Int. 42, 18859–18869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.09.033 (2016).

Han, M., Kang, D. & Yoon, K. Efficient paper mosaic rendering on mobile devices based on position-based tiling. J. Real-Time Image Proc. 9, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11554-013-037 (2014).

Doyle, L., Anderson, F., Choy, E. & Mould, D. Automated pebble mosaic stylization of images. Comp. Vis. Media 5, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41095-019-0129-0 (2019).

Dabhekar, K., More, S. R. & Khedikar, I. Study of partial replacement of coarse aggregate by mosaic tile chips. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 7. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12521.31849 (2021).

Pachta, V., Marinou, P. & Stefanidou, M. Development and testing of repair mortars for floor mosaic substrates. J. Build. Eng. 20, 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.08.019 (2018).

Miriello, D. et al. Compositional study of mortars and pigments from the Mosaico Della Sala dei Draghi E dei Delfini in the archaeological site of Kaulonía (Southern Calabria, Magna Graecia, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 9, 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-015-0285-9 (2017).

Peganant, P. & Koomsap, P. Improving decision making in product flow-based tiling automation for custom mosaic design. Assem. Autom. 37, 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/aa-07-2016-085 (2017).

Museros, L. & Escrig, M. T. A qualitative theory for shape representation. Intell. Artif. 8. https://doi.org/10.4114/ia.v8i23.801 (2004).

Cichocka, M. O., Bolhuis, M., Van Heijst, S. E. & Conesa-Boj, S. Robust Fabrication of Large-Area in- and Out-of-Plane Cross-Section Samples of Layered Materials with Ultramicrotomy. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1912.06003 (2019).

Cayiroglu, I. & Demir, B. E. Computer assisted glass mosaic tiling automation. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 28, 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2012.02.008 (2012).

Oral, A. & Erzincanlı, F. Computer-assisted robotic tiling of mosaics. Robotica 22, 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263574703005484 (2004).

Oral, A. Patterning automation of square mosaics using computer assisted SCARA robot. Robotica 27, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263574708005304 (2009).

Liu, C. H., Jeyaprakash, N. & Yang, C. H. Material characterization and defect detection of additively manufactured ceramic teeth using non-destructive techniques. Ceram. Int. 47, 7017–7031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.11.052 (2021).

Dong, G. et al. A rapid detection method for the surface defects of mosaic ceramic tiles. Ceram. Int. 48, 15462–15469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.02.080 (2022).

Tout, K., Meguenani, A., Urban, J. P. & Cudel, C. Automated vision system for magnetic particle inspection of crankshafts using convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 112, 3307–3326. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00170-020-06467-4 (2021).

Chen, R. S., Lu, K. Y., Yu, S. C., Tzeng, H. W. & Chang, C. C. A case study in the design of BTO/CTO shop floor control system. Inf. Manag. 41, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00003-X (2003).

Zahmani, M. H. & Atmani, B. A Data Mining based dispatching rules selection system for the job shop scheduling problem. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 18, 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219686719500021 (2019).

Banerjee, C., Doppalapudi, T. K., Pasiliao, E. & Mukherjee, T. Deep feature learning for intrinsic signature based camera discrimination. Big Data Min. Anal. 5, 206–227. https://doi.org/10.26599/BDMA.2022.9020006 (2022).

Kaya, B., Berkay, A. & Erzincanli, F. Robot assisted tiling of glass mosaics with image processing. Ind. Robot. Int. J. 32, 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/01439910510614655 (2005).

Hung, S. C., Liu, T. Y. & Tsai, W. H. A new approach to automatic generation of tile mosaic images for data hiding applications. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 41, 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1109/78.193202 (2002).

Oral, A. & Inal, E. P. Marble mosaic tiling automation with a four degrees of freedom cartesian robot. Rob. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 25, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2008.04.003 (2009).

Museros, L., Falomir, Z., Velasco, F., Gonzalez-Abril, L. & Martí I. 2D qualitative shape matching applied to ceramic mosaic assembly. J. Intell. Manuf. 23, 1973–1983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-011-0524-6 (2012).

Han, M., Kang, D. & Yoon, K. Efficient paper mosaic rendering on mobile devices based on position-based tiling. J. Real-Time Image Proc. 9, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11554-013-0371-0 (2014).

Dong, G. et al. Application of machine vision-based NDT technology in ceramic surface defect detection—a review. Mater. Test. 64, 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1515/mt-2021-2012 (2022).

Falomir, Z., Museros, L., Gonzalez-Abril, L. & Velasco, F. Measures of similarity between qualitative descriptions of shape, colour and size applied to mosaic assembling. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 24, 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2013.01.013 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, Project No. 2021YFB4001501, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Project No.62461029, the Fund of Science and Technology Program of Jingdezhen City, Project No. 2023GY001-13, the Fund of Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou City, Project No.SL2023A04J01572, and the Fund of Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, Project No. 2023A1515110166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P.D. wrote the manuscripts, made the ideas, conceived the experiments and acquired the funding, R.Y. wrote the manuscript, collected and analyzed the experimental data, and revised the manuscript, X.Z.X., X.Y.K., N.S.W., X.Y.C., H.F., Z.X.W. reviewed and edited the manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, G., You, R., Xu, X. et al. Automatic tiling method for mosaic ceramic art images based on subpixel edge fitting localization and collaborative operation of multiple manipulators. Sci Rep 14, 23215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74567-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74567-2