Abstract

Carbon with depleted d13C (down to − 25.6‰ VPDB) found in > 3.7 billion year old metamorphic sediments from the Isua Supracrustal Belt, Southwestern Greenland, has been proposed to represent the oldest remains of life on Earth. Graphitic inclusions within garnet porphyroblasts from this locality have been shown to associate with elements consistent with biogenic remains. In this report, we focus on certain liquid inclusions found in the Isua garnets, characterizing their chemical composition using atomic force microscopy, AFM-based infrared spectroscopy, optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry. Our results show that the liquid inclusions contain functional groups consisting of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in a configuration similar to amide functional groups. We suspect that the amide groups formed from N, O and C-containing volatile components that were released from the original kerogenous material enclosed in the garnets, as this was graphitized during thermal maturation. This is consistent with the observed inclusion assemblage of solid graphitic and viscous fluid inclusions alike. Our observations are compatible with the inclusions forming from biogenic precursor material, and when considered alongside previous reports on the carbonaceous material in the Isua metamorphic sediments, these and our study collectively indicate that the carbonaceous material in the Isua metasediments represents the oldest traces of life on Earth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Identification and characterization of biogenic remains in the oldest rocks on Earth have implications for the timing and early evolution of life on Earth1. Structural evidence (e.g. stromatolites, microfossils) is among the more compelling types of evidence for life preserved in rocks, the oldest of which appear in the ~ 3.5 billion years old (Ga) rock units of the Pilbara Craton, Australia2,3, and the Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa4,5. Older evidence of biological activity is harder to come by due to the scarcity of Eoarchean (> 3.6 Ga) terranes. Furthermore, the deformation and metamorphism experienced by the few Eoarchean terranes that do exist obscure most structural or morphological biogenic traces that might be present, making interpretation of such structures contentious6,7. In other cases, reports of structures in Eoarchean cherts reminiscent of microorganisms have been suggested to be formed through abiotic processes8,9,10.

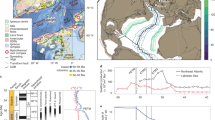

The ≥ 3.7 Ga rocks of the Isua Supracrustal Belt (ISB) (Fig. 1a) are among the oldest supracrustal rocks on the planet11. Graphite-rich layers are found in finely laminated metasediments (Fig. 1b), indicating slow pelagic deposition in an oceanic setting12. Previous studies have shown that the graphite in the metasediments display characteristics consistent with biogenicity in the form of low carbon isotope ratios12,13,14, nanostructural domains within the graphite crystals14, and identification of oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorous functional groups in the graphite found as inclusions within garnet porphyroblasts in the ISB (Fig. 1c)15. The occurrence of the graphite as fine, discrete horizons within a metamorphosed oceanic sediment further suggests that the graphite was originally deposited as organic detritus on the sea floor13. A more detailed description of the geology of the ISB is found in the supplementary text.

Isua Supracrustal Belt graphite inclusions. (a) Regional map of the ISB. Sampling location marked by a black square. Location of ISB in Greenland indicated on the smaller map. (b) Metapelite rocks within the Garbenschiefer unit display light intervals of turbidite deposition and black intervals of pelagic deposition of carbon-rich sediments. (c) Photomicrographs of thin section of garnet-biotite-epidote schist show layers of graphite enclosed within the garnets, which have often subsequently been rotated. Red arrows indicate straight layers of graphite preserved inside the garnet crystal. Subfigures (a) and (b) adapted with permission from Ref.15.

Previous studies also identified fluid inclusions occurring alongside the solid graphite within garnets in the ISB metasediments15. In this study, we characterize the chemistry of residues of these liquid inclusions left on fresh fracture surfaces by atomic force microscopy (AFM), AFM coupled with infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR), scanning electron microscopy energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDXS), optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy (O-PTIR), Raman spectroscopy, and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) and evaluate their formation history and relation to the solid graphitic inclusions.

Results

Dried-up inclusion residues

Resinous µm-sized domains with lobate or dendritic appearances are observed coating fracture surfaces of eight different garnet porphyroblasts after we cracked these open (cf. “Materials and methods”), some garnets containing several domains (Supplementary Fig. S1a–j). Their adherence to newly exposed surfaces on fractured garnets suggest that they originated as pressurized inclusions, and their morphologies suggest the that they were ejected as fluids that splashed out on the surface of the fragments. The fractures likely ran along the inclusions in part due to the presence of high pressure fluids here. Upon ejection, the most volatile fractions rapidly evaporated, leaving a viscous, resinous dried-up residue. The exposed viscous inclusion residues are often spatially associated with solid graphitic inclusions (e.g. Supplementary Fig. S1a, d).

Our AFM analyses yield images of high spatial and topographic resolution of the viscous residues derived from the liquid inclusions (Fig. 2). The AFM images show that the dried-up residues vary in thickness, and generally possess thicker edges and inward-facing lobes bounding centers which are depressed by 20–40 nm relative to the bounding lobes. Based on the AFM images, the estimated volumes of the dried-up liquid inclusion residues, after decompression and evaporation of the most volatile fractions from the original inclusions, range from 0.64 to 58.7 ± 10.0 μm3 (Supplementary Table S1).

Liquid inclusion residues. Photomicrograph (a), AFM image (b) and AFM height profile (c) of inclusion residue shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a. Red arrows in (a) indicate enclosed sedimentary layers of graphitic material. Photomicrograph (d), AFM image (e) and AFM heigh profile (f) of inclusion residue shown in Supplementary Fig. S1b. White outline in (a) and (d) indicates area of AFM images. Points in (b) and (e) labelled SX.X indicate position of AFM-IR spectrum acquisition, and red squares indicate position of AFM-IR maps (Supplementary Fig. S4). R1 in (b) refers to point of acquisition of Raman spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S3). Green and blue lines indicate positions of height profiles.

Raman point spectra and maps (Supplementary Fig. S3) reveal graphite-related peaks (~ 1580 cm− 1 G-peak, ~ 1370 cm− 1 lattice disorder D-peak and ~ 2750 cm− 1 2D-peak)16 along with garnet-related peaks (908 cm− 1)17. The graphite-related peaks were observed on the dried-up liquid inclusion residues, on the solid graphitic inclusions and to a lesser extent on the barren garnet surface. It is likely that the graphite Raman peaks observed in the dried-up liquid inclusion residues arise from solid graphitic inclusions present beneath the surface, as the spatial distribution of the graphite-like peaks does not always correlate with the occurrence of the residues (e.g. Supplementary Fig. S3b,c). The presence of graphite-related Raman shift peaks in the dried-up liquid inclusion residues thus probably arise because of a close spatial relationship with the solid graphite inclusions. The Raman spectral characteristics of the graphite probed with the Raman laser shows D-peak/G-peak intensity ratios averaging 0.22 ± 0.10 (1 σ, n = 10), indicating high degree of metamorphic graphitization18.

Presence of amide groups

Infrared spectra were recorded with high spatial resolution with AFM-IR such that spectra from the dried-up liquid inclusions could be directly compared to background spectra recorded on the barren garnet surface (Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Figs. S4–S7). IR absorption from the dried-up liquid inclusions was ubiquitously characterized by a sharp peak at 1280 cm− 1 and a broader peak centered around 1660 cm− 1. These two peaks are observed in nearly all the dried-up liquid inclusion residues examined and are the only peaks which are unambiguously unique to the residues. AFM-IR absorption intensity maps (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Figs. S4–S6) further show clear association of the 1280 cm− 1 and 1660 cm− 1 vibrations with the dried-up liquid inclusion residues. O-PTIR-based IR maps also highlight the presence of the ~ 1660 cm− 1 peak along a band of solid graphitic inclusions (Fig. 3d), supporting that the two types of inclusions are genetically related. Little to no absorption was observed in the 2800–3600 cm− 1 region of most spectra (however cf. Supplementary Fig. S5 and supplementary text), suggesting low amounts of O–H and C–H groups19. The low amount of hydrogenous groups may be due to hydrogen escape from the inclusions through the garnet lattices20,21, or by immediate evaporation of the more volatile (hydrogen bearing) fractions during opening of the garnet crystal. Discussions of the AFM-IR detection limits and possible contaminants are found in the supplementary text.

IR absorption analyses of liquid inclusion residues and solid graphitic inclusions. (a) AFM-IR spectra recorded on and next to dried-up liquid inclusion residues in garnets (cf. Fig. 2 for locations). Two vibrational bands around 1280 cm− 1 and 1660 cm− 1 are readily apparent (even more so in the garnet background-subtracted spectra S1.1–S1.2 and S2.2–S2.1). The grey-shaded area indicates the region of the spectrum in which the OPO power significantly drops; the recorded intensities in this region thus carry no spectral information. (b,c) AFM-IR maps of absorption intensities at around 1280 cm− 1 recorded on the dried-up liquid inclusion residues further show this signal is confined to the residues (cf. Fig. 2 for location; corresponding maps of 1660 cm− 1 peak intensities are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4). O-PTIR map (d) of 1653 cm− 1 IR absorption intensity shows how this signal is observed along a line of solid graphitic inclusions (see Supplementary Fig. S1a for location). IR absorption intensities in (b–d) are not to scale.

IR absorption peaks at 1660 cm− 1 or 1280 cm− 1 are uncommon in kerogens. Principal component analyses of large datasets of IR spectra of kerogens have identified absorption bands centered around 1640 cm− 1 and 1240 cm− 1 as the most important bands for predicting the amount of nitrogen in natural sedimentary kerogen, reflecting two of the typical three amide IR bands22. These two bands are roughly comparable to our observed peaks, the absorption frequencies apparently shifted to higher wavenumbers. A large, complex, cross-linked geopolymer such as kerogen is likely to yield IR absorption bands deviating from the band positions known for smaller organic molecules with well-constrained structures, due to a more complex chemical coordination environment, and perhaps especially so in our samples, given the apparent diminished amounts of hydrogen. Our ToF-SIMS data (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. S9–S11) is consistent with the presence of C-, H-, O- and N-containing chemical species in the dried-up liquid inclusion. Thus, the 1660 cm− 1 absorption peak could be ascribed to C=O stretch from an amide-associated carbonyl group23,24, and the 1280 cm− 1 can be ascribed to the amide C–N stretch band present in this region24, these two bands respectively representing the amide I and III bands typically associated with amides. The amide II N–H bending band19 was not observed in the samples. The absence of the amide II band is likely due to the generally diminished amounts of hydrogen in the samples. As such, the AFM-IR and ToF-SIMS data obtained from the dried-up liquid inclusion residues are individually and collectively consistent with the presence of some type of C, N and O-containing compound in a configuration similar to that of amide functional groups, displaying infrared vibrational patterns consistent with amide bands I and III.

ToF-SIMS images of liquid inclusion residue. The inclusion residue (cf. Supplementary Fig. S1b for optical photomicrograph) can be made out in the high spatial resolution total ion map (a)—note that the two right-most lobes observed in Supplementary Fig. S1b are not discernible on the ToF-SIMS map. High mass resolution (low spatial resolution) ion maps (same area as in a) shown a CxHy contaminant signal covering the surface indiscriminately (b), while CxHyOz+ species (c) and NOx+ species (d) are observed in the inclusion residue only. The intensity variation in (b) is reflecting the topography of the surface, with areas closer to the extractor yielding higher secondary ion counts.

Discussion

Amide vibrational bands are typically associated with IR spectra of proteins25. Nitrogenous organic compounds including amides have been identified using synchrotron-based X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) in organic fossils from the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool cherts, Pilbara, Australia26, from the equally old Buck Reef cherts of Barberton, South Africa27, and from the 1.88 Ga Gunflint chert from North America28, and they have been observed in microorganisms artificially matured at temperatures of 250 degrees C and 250 bars pressure29. These studies indicate that nitrogenous biological compounds can be preserved with some fidelity, in rocks affected by moderately high temperatures and pressure. However, considering the thermal history of the ISB rocks, the samples studied here are unlikely to contain preserved nitrogenous domains of proteinaceous remains30,31. Based on the IR spectra of the dried-up inclusion residues, their chemistry is much more simple than that observed with XANES in aforementioned organic microfossils26,27,28, and no biological compounds were observed in any recognizable condition in the dried-up inclusion residues, which is most easily explained by the material being ancient, in a thermally altered state and thus not contaminated with recent biomatter.

Origin of amides

Formation of volatiles such as CO2, CO, CH4, H2 and H2O is an essential process during thermal maturation and graphitization of sedimentary organic matter and kerogens and is important in the formation of oil from source rock kerogens32,33. Nitrogen is also devolatilized from kerogen during thermal maturation, with amino groups having been shown to be released from kerogens at temperatures below 510 °C34. Nitrogen is found in relatively high abundances in clays and correspondingly in micas in metamorphic rocks in the form of ammonium, as it may substitute for potassium ions35. Ammonium abundances in ISB have been shown to correlate with the graphite-rich sedimentary fractions in schists36, and the nitrogen contents in the metasediments have been observed correlating with potassium concentrations37. While the direct biomarker potential of nitrogen in graphite and graphitic sediments has been questioned38, the sheer abundance of nitrogen observed in the ISB detrital metasediments is most easily reconciled with the degradation of biogenic matter36,39. Stepped-combustion/pyrolysis studies of graphite from various lithologies of the ISB, including detrital metasediments, indicate that the majority of intercalated and strongly bound nitrogen in graphite may have been incorporated via diffusion from the potassic minerals of the rock40.

The garnet inclusions studied here represent a system less open to diffusion, and any intercalation or substitution of nitrogen from surrounding minerals would have to have taken place prior to enclosure in the garnets. If the carbonaceous material was enclosed in the garnets prior to being fully graphitized, it is likely that the volatiles subsequently released from the material during thermal maturation would remain inside the garnets, forming the fluid inclusions observed in this study. As such, thermal evolution and graphitization of the enclosed carbonaceous material could yield an inclusion assemblage consisting both of liquid and solid graphitic inclusions.

Abiotic formation of amides in natural sedimentary environments has been documented by previous studies and suggested to be the product of Maillard condensation reactions between sugars and amino acids resulting in amides as well as N-heterocyclic compounds41. A different reaction pathway describes the amidation of esters with sedimentary ammonium42, resulting in the formation of alkyl amides. Additional abiotic pathways for amide formation includes condensation of amines and carboxylic acids under hydrothermal conditions43, and similar reactions are thought to have produced abiotic amide compounds observed in some carbonaceous chondrites44,45. Thus, amide-like compounds are readily produced from reactions between carbonaceous and nitrogenous compounds. The volatiles constituting the liquid inclusions within the garnets studied here would have likely been a mixture of carbonaceous and nitrogenous compounds, as these are commonly released during thermal maturation of kerogens32. The amides observed here could thus be part of the equilibrium product between these volatile components, formed from abiotic condensation of volatiles of a biotic kerogenous source.

Fluid hydrocarbon inclusions have been reported from the Archean Kaapvaal (South Africa) and Pilbara cratons46,47. Furthermore, fluid inclusions in Archean and younger rocks have shown oil preservation at temperatures of up to 350–450 °C48,49. Our observations here indicate that fluid inclusions may remain inside mineral grains in spite being heated above 500 °C.

Multiple organic sulfur compounds have been reported from fluid inclusions found in barites (BaSO4) in the 3.5 Ga hot-spring formations of the Dresser Formation, Pilbara, which were ascribed to abiotic and biotic sources alike50. Although no amides were recovered from the Dresser barites, N2 was observed in some of the inclusions. This compositional discrepancy between the compounds observed in the Dresser barites and the inclusion assemblage observed in the ISB metapelites may be ascribed to vastly different depositional environments and taphonomic histories.

Biogenicity of inclusion assemblage

The graphite co-occurring with the liquid inclusions studied here has been suggested to have a biogenic origin in multiple previous studies12,13,14,15,51. The carbonaceous inclusion assemblage would have originated as organic detritus, which was subsequently kerogenized and graphitized. Multiple abiotic mechanisms are known to yield graphite with biogenic-like isotopic signatures without invoking biological precursor materials52. Disproportionation of siderite (FeCO3) into magnetite (Fe3O4), carbon dioxide and graphite can explain the presence of graphite in some parts of the ISB, where graphite occurs in close association with siderite and magnetite53,54. However, no magnetite or siderite is observed in our samples, and disproportionation of siderite can therefore not account for the presence of graphite in our samples. Similarly, graphite can precipitate from CO2–CH4–H2O-rich hydrothermal fluids at temperatures as low as 500 °C55, which has been demonstrated for the occurrence of graphite in the Eoarchean Akilia gneisses56, 150 km SW of the ISB. Graphite has also been observed as precipitates within fluid inclusions57, and as such could also explain the observed assemblage of a solid graphitic fraction occurring alongside a liquid fraction in the ISB garnets. Although there are no immediate indications in the sample of pervasive hydrothermal fluid migration, such as secondary veining, hydrothermal precipitation cannot be ruled out. However, considering the occurrence of the graphite as discrete, contiguous horizons parallel to the sedimentary bedding features of the metapelite, it is more likely that the graphite precursor material was deposited as part of a sedimentary sequence as fine, pelagic detritus.

Previous studies have suggested a biogenic origin for the graphite hosted in the ISB detrital metasediments12,13,14,15,51 primarily on account of its isotopic and elemental composition and its mode of occurrence. The current study further indicates the presence of nitrogen and oxygen in association with the graphite, occurring as part of an assemblage of both liquid carbonaceous and graphitic inclusions. We consider the most likely scenario for emplacement of such an assemblage as resulting from the enclosure of detrital organic material within the garnets prior to the complete graphitization of it. The amide signal may be a result of the reaction between carbonaceous, hydrous, and nitrogenous volatiles released from the organic matter as it was thermally matured. As such, our results are compatible with a biogenic precursor for the carbonaceous material observed in ISB detrital sediments. When considered together, the multiple lines of evidence, in the shape of low carbon isotope ratios12,14, nanostructural characteristics14, mode of occurrence as pelagic deposits in a marine detrital sediment12,13,58, and the abundance of nitrogen occurring in the sediment matrix36,37 and in the graphite itself15,40, represents compelling evidence that the graphitic and carbonaceous matter present in the ISB rocks constitutes remains of Eoarchean marine life forms.

Materials and methods

Material sampling and preparation

The garnets (sample #030048 of Ref.15) are from a block of minimally-deformed metamorphosed detrital sediments sampled 4 m along strike from the image in Fig. 1b. Garnets were chosen for this study because of their low internal diffusivity and mechanical robustness. The garnets were liberated from the metapelite using Selfrag® high voltage power pulse technology to separate the rock into its component crystals, after which the garnets were identified and picked out by hand. The garnets were 0.5–2 mm in diameter. Garnets were cleaved by squeezing between two glass slides, which had been cleaned accordingly: washing with soap, followed by ethanol, and then demineralized, ultrapure Milli-Q® water, before finally being exposed to UV-generated ozone for 10–20 min. Prior to crushing, the garnets were painted with silver paint (Agar, G3790 Conductive Silver Paint) such that the fresh fracture surface of the garnets could easily be identified after cleaving them. The cleaved garnets were transferred directly onto adhesive tape on AFM sample discs without touching the garnet fragments.

Optical microscopy

Reflected light photomicrographs were taken through a Zeiss Axio Imager.A1m microscope fitted with Zeiss lenses with a Zeiss Axiocam 208 color camera.

AFM imaging

AFM images were captured in air using an Asylum Research MFP3D AFM in AC mode. The tips used were Olympus AC240 silicon probes with a spring constant of 2 nN nm− 1 and a resonance frequency of 70 kHz.

AFM analyses did not leave physical traces on the inclusion samples, but marks resulting from AFM-IR analyses were observed (see supplementary text).

The height profiles shown are flattened, assuming a steady, uniform garnet substrate surface topography underneath the dried-up liquid inclusion residues. The garnet surfaces exhibit a conchoidal topography.

SEM-EDXS

SEM image was captured using an FEI Quanta 650 F Scanning Electron Microscope. The image was taken using a 10 kV electron acceleration voltage in low vacuum mode with a large field detector at a working distance of 10.7 mm.

The SEM was fitted with two Bruker 30 mm2 Energy Dispersive Spectrometers for elemental EDXS analysis.

AFM-IR

AFM-IR analyses were performed on an Anasys NanoIR2 system in air in contact mode using custom Anasys NanoIR NIR2 tips (spring constants between 0.07 and 0.4 nN nm− 1). The NanoIR2 system uses an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) covering the IR range from 900 to 3600 cm− 1. The IR signal was optimized through alignment of the OPO and the AFM tip typically at 3–4 points throughout the spectrum range. The spectral resolution of the single spectrum data was 4 cm− 1, with each point in the spectrum representing the average signal from 256 OPO pulses. The spectra shown in the study are subjected to a Savitzky–Golay filter (polynomial order of 3 and 6 side points). For the IR intensity mapping, each pixel represents the intensity at the given wavenumber averaged over 16 OPO pulses. The maps were recorded at a scan rate of 0.1 Hz.

The OPO was not capable of covering the whole range 900–3600 cm− 1 without switching between two sets of crystals. The switch between one nonlinear crystal setup to the other takes place at 2235 cm− 1, around which wavenumber the power drops, as one crystal setup loses power and the subsequent setup picks up power. This drop in power results in loss of spectral information in the region ∼2235–2380 cm− 1, as indicated by a greyed-out area in the spectra. The recorded absorption intensities in this region thus carries no significant spectral information.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra in Supplementary Fig. S3c were recorded on a Thermo Fisher™ DXR® Raman microscope fitted with a 455 nm laser. The ‘R1’ and ‘adjacent garnet’ spectra were acquired at 3 mW and 5 mW laser power, respectively. Both spectra were averaged over 3 acquisitions 10 s exposure time at the same spot through a 50× objective.

Raman shift intensity maps (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b) were recorded using a mIRage® O-PTIR microspectroscope (Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.) (see “O-PTIR mIRage” section).

ToF-SIMS

ToF-SIMS analyses were performed on fresh-fracture surfaces of the garnets in a ToF-SIMS IV instrument (ION-TOF GmbH) using a 25 keV Bi3+ beam operated at 0.1 pA. Before the analyses the surfaces were pre-cleaned by sputtering using a 10 keV C60+ beam operated at 1.3 nA for 10 s. Analyses were performed in two different modes: high mass resolution mode (∼ 5000–7000 m/Δm resolution at m/z 30) covering a m/z range of 0–2000 and high spatial resolution mode (Δl ∼ 500 nm, ∼ 200 m/Δm at m/z 30) covering a m/z range of 0–800. Several 80 by 80 μm to 200 by 200 μm areas covering the dried-up liquid inclusion residue and the surrounding area were analyzed. As the samples were insulating, the sample surface was flooded with electrons for charge compensation.

O-PTIR mIRage

Optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy (O-PTIR) combined Raman spectroscopy was carried out on a mIRage® microspectroscope (Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp., Santa Barbara, USA). The PTIR software (vers. 4.3.7478) of the same manufacturer was used for data acquisition and processing.

O-PTIR spectroscopy operates in reflection mode, i.e. contactless, and couples broadly tunable pulsed IR laser sources covering the standard IR spectral range with a short wavelength visible laser and results in submicron IR spectroscopy. Since the probe laser (QCL 532 nm) can simultaneously act as a Raman excitation source, O-PTIR can provide simultaneous IR and Raman spectroscopic analysis of the same sample location at the same resolution. O-PTIR excites the molecular vibrations of the sample in the spectral range of 800–1800 cm− 1.

For IR measurements, first a background calibration was employed. For this, the whole spectral range was collected 30 times on a silicone cantilever and the average was saved as background data. This procedure allows the subtraction of background noise from the actual IR signals. Both IR and Raman measurements were done at room temperature (21–25 °C) and at a humidity of less than 0.5%. For IR measurements, the power of IR laser was set to 10 or 22% at a pulse rate of 100 kHz, a pulse width of 500 ns and a duty cycle of 5%. The power of the probe laser was set to 0.5%. Data was collected at a spectral resolution of 6.6 cm− 1 with a point density of 2 cm− 1/pt. The sweep speed was set to 100 cm− 1. The data was averaged 2–3 times.

For Raman measurements the probe power was set to 6–10% and data was collected with a resolution of 1800 points at a point density of 0.53 cm− 1/pt and an integration time of 5 s. Each presented Raman spectrum represents the average of 6–20 measurements.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Raw data files used to produce the figures and tables in this report is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Pearce, B. K. D., Tupper, A. S., Pudritz, R. E. & Higgs, P. G. Constraining the time interval for the origin of life on earth. Astrobiology. 18, 343–364 (2018).

Allwood, A. C., Walter, M. R., Kamber, B. S. & Marshall, C. P. Burch, I. W. Stromatolite reef from the early archaean era of Australia. Nature. 441, 714–718 (2006).

Djokic, T., Van Kranendonk, M. J., Campbell, K. A., Walter, M. R. & Ward, C. R. Earliest signs of life on land preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga hot spring deposits. Nat. Commun. 8, 15263 (2017).

Homann, M. Earliest life on earth: evidence from the Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa. Earth Sci. Rev. 196, (2019).

Tice, M. M. & Lowe, D. R. Photosynthetic microbial mats in the 3,416-Myr-old ocean. Nature. 431, 549–552 (2004).

Nutman, A. P., Bennett, V. C., Friend, C. R. L., Van Kranendonk, M. J. & Chivas, A. R. Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature. 537, 535–538 (2016).

Allwood, A. C., Rosing, M. T., Flannery, D. T., Hurowitz, J. A. & Heirwegh, C. M. Reassessing evidence of life in 3,700-million-year-old rocks of Greenland. Nature. 563, 241–244 (2018).

Dodd, M. S. et al. Evidence for early life in Earth’s oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates. Nature. 543, 60 (2017).

Papineau, D. et al. Metabolically diverse primordial microbial communities in Earth’s oldest seafloor-hydrothermal jasper. Sci. Adv. 8, 2296 (2022).

McMahon, S. Earth’s earliest and deepest purported fossils may be iron-mineralized chemical gardens. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 286, (2019).

Nutman, A. P., Friend, C. R. L. & Paxton, S. Detrital zircon sedimentary provenance ages for the Eoarchaean Isua supracrustal belt southern West Greenland: juxtaposition of an imbricated ca. 3700 Ma juvenile arc against an older complex with 3920–3760 ma components. Precambrian Res. 172, 212–233 (2009).

Rosing, M. T. 13C-depleted carbon microparticles in ≥ 3700-Ma sea-floor sedimentary rocks from west Greenland. Science. 283, 674–676 (1999).

Rosing, M. T. & Frei, R. U-rich archaean sea-floor sediments from Greenland—indications of > 3700 Ma oxygenic photosynthesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 217, 237–244 (2004).

Ohtomo, Y., Kakegawa, T., Ishida, A., Nagase, T. & Rosing, M. T. evidence for biogenic graphite in early archaean isua metasedimentary rocks. Nat. Geosci. 7, 25–28 (2014).

Hassenkam, T., Andersen, M. P., Dalby, K. N., Mackenzie, D. M. A. & Rosing, M. T. Elements of Eoarchean life trapped in mineral inclusions. Nature. 548, 78–81 (2017).

Ferrari, A. C. Raman spectroscopy of graphene and graphite: disorder, electron-phonon coupling, doping and nonadiabatic effects. Solid State Commun. 143, 47–57 (2007).

Kolesov, B. A. & Geiger, C. A. Raman spectra of silicate garnets. Phys. Chem. Miner. 25, 142–151 (1998).

Robert, A. M. et al. Evidence and origin of different types of sedimentary organic matter from a paleoproterozoic orogenic au deposit. Precambrian Res. 299, 319–338 (2017).

Williams, D. & Fleming, I. Spectroscopic Methods in Organic Chemistry (McGraw-Hill, 2008).

Blanchard, M. & Ingrin, J. Hydrogen diffusion in Dora Maira Pyrope. Phys. Chem. Miner. 31, 593–605 (2004).

Wang, L., Zhang, Y. & Essene, E. J. Diffusion of the hydrous component in pyrope. Am. Mineral. 81, 706–718 (1996).

Alaoui, G., Léger, M. N., Gagné, J. P. & Tremblay, L. Assessment of estuarine sediment and sedimentary organic matter properties by infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Chem. Geol. 286, 290–300 (2011).

Parker, F. S. Amides and amines. In Applications of Infrared Spectroscopy in Biochemistry, Biology, and Medicine (ed. Parker, F. S.) 165–172 (Springer US, 1971). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-1872-9_8

Smith, B. & Organic Nitrogen Compounds, V. I. I. Amides—the Rest of the story. Spectroscopy. 35, 10–15 (2020).

Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenergetics. 1767, 1073–1101 (2007).

Alleon, J. et al. Chemical nature of the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool microfossils. Geochem. Persp Lett. 37–42. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1817 (2018).

Alleon, J., Bernard, S., Olivier, N., Thomazo, C. & Marin-Carbonne, J. Inherited geochemical diversity of 3.4 Ga organic films from the Buck reef chert, South Africa. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1–7 (2021).

Alleon, J. et al. Molecular preservation of 1.88 Ga Gunflint organic microfossils as a function of temperature and mineralogy. Nat. Commun. 7, 11977 (2016).

Alleon, J. et al. Organic molecular heterogeneities can withstand diagenesis. Sci. Rep. 7, 1508 (2017).

Eglinton, G. & Logan, G. A. Molecular preservation. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 333, 315–328 (1991).

Briggs, D. E. G. & Summons, R. E. Ancient biomolecules: their origins, fossilization, and role in revealing the history of life. BioEssays. 36, 482–490 (2014).

Tissot, B. P. & Welte, D. H. Petroleum Formation and Occurrence (Springer, 1984).

Killops, S. D. & Killops, V. J. Introduction to Organic Geochemistry (Blackwell, 2005).

Kelemen, S. R., Freund, H., Gorbaty, M. L. & Kwiatek, P. J. Thermal chemistry of nitrogen in kerogen and low-rank coal. Energy Fuels. 13, 529–538 (1999).

Mysen, B. Nitrogen in the Earth: abundance and transport. Prog Earth Planet. Sci. 6, 38 (2019).

Honma, H. High ammonium contents in the 3800 Ma Isua supracrustal rocks, central West Greenland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 60, 2173–2178 (1996).

Stüeken, E. E., Boocock, T., Szilas, K., Mikhail, S. & Gardiner, N. J. Reconstructing nitrogen sources to earth’s earliest biosphere at 3.7 Ga. Front. Earth Sci. 9, (2021).

Stüeken, E. E. Nitrogen in ancient mud: a biosignature? Astrobiology 16, 730–735 (2016).

Stüeken, E. E., Szilas, K. & van Hinsberg, V. J. Evaluating the biosignature potential of nitrogen concentrations in graphite and associated K-silicates. Chem. Geol. 617, (2023).

Van Zuilen, M. A. et al. Nitrogen and Argon isotopic signatures in graphite from the 3.8-Ga-old Isua Supracrustal Belt, Southern West Greenland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 69, 1241–1252 (2005).

Jokic, A., Schulten, H. R., Cutler, J. N., Schnitzer, M. & Huang, P. M. A significant abiotic pathway for the formation of unknown nitrogen in nature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, (2004).

McKee, G. A. & Hatcher, P. G. Alkyl amides in two organic-rich anoxic sediments: a possible new abiotic route for N sequestration. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 74, 6436–6450 (2010).

Fu, X. et al. Direct synthesis of amides from amines and carboxylic acids under hydrothermal conditions. ACS Earth Space Chem. 4, 722–729 (2020).

Cooper, G. W. & Cronin, J. R. Linear and cyclic aliphatic carboxamides of the Murchison meteorite: hydrolyzable derivatives of amino acids and other carboxylic acids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 59, 1003–1015 (1995).

Rotelli, L. et al. The key role of meteorites in the formation of relevant prebiotic molecules in a formamide/water environment. Sci. Rep. 6, 38888 (2016).

Buick, R., Rasmussen, B. & Krapez, B. Archean oil: evidence for extensive hydrocarbon generation and migration 2.5–3.5 Ga. AAPG Bull. 82, 50–69 (1998).

Dutkiewicz, A., Rasmussen, B. & Buick, R. Oil preserved in fluid inclusions in archaean sandstones. Nature. 395, 885–888 (1998).

George, S. C. et al. Oil-bearing fluid inclusions from the Palaeoproterozoic: a review of biogeochemical results from time-capsules > 2.0 Ga old. Sci. China, Ser. D Earth Sci. 52, 1–11 (2009).

Hoffmann, C. F., Henley, R. W., Higgins, N. C., Solomon, M. & Summons, R. E. Biogenic hydrocarbons in fluid inclusions from the Aberfoyle tin-tungsten deposit. Chem. Geol. 70, 287–299 (1988).

Mißbach, H. et al. Ingredients for microbial life preserved in 3.5 billion-year-old fluid inclusions. Nat. Commun. 12, (2021).

Hassenkam, T. et al. Direct evidence for Eoarchean iron metabolism? Geobiology 19, 218–227 (2021).

Alleon, J. & Summons, R. E. Organic geochemical approaches to understanding early life. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 140, 103–112 (2019).

Van Zuilen, M. A., Lepland, A. & Arrhenius, G. Reassessing the evidence for the earliest traces of life. Nature. 418, 627–630 (2002).

Van Zuilen, M. A. et al. Graphite and carbonates in the 3.8 Ga old Isua Supracrustal Belt, southern West Greenland. Precambrian Res. 126, 331–348 (2003).

Luque, F. J. et al. Deposition of highly crystalline graphite from moderate-temperature fluids. Geology. 37, 275–278 (2009).

Lepland, A., Van Zuilen, M. A. & Philippot, P. Fluid-deposited graphite and its geobiological implications in early Archean gneiss from Akilia. Greenl. Geobiology. 9, 2–9 (2011).

Satish-Kumar, M. Graphite-bearing CO2-fluid inclusions in granulites: insights on graphite precipitation and carbon isotope evolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 69, 3841–3856 (2005).

Boyd, A. J., Rosing, M. T., Harding, M. A. R., Canfield, D. E. & Hassenkam, T. 3.7 billion year old detrital sediments in Greenland are consistent with active plate tectonics in the Eoarchean. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 201 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible through financial support provided by the Novo Nordisk foundation through the NERD program, grant number NNF21OC0068372 given to TH. SS was supported by Swedish National Space Agency (Contracts 137/19 and 2021- 00092).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MARH: Investigation (AFM, NanoIR, ToF-SIMS, SEM-EDXS, Raman spectroscopy), formal analysis, visualization, writing (original draft, review and editing). AJB: Investigation (ToF-SIMS, SEM-EDXS), writing (review and editing). SS: Investigation (ToF-SIMS), writing (review and editing). AS: Investigation (Raman spectroscopy), writing (review and editing). MS and PA: Investigation (O-PTIR), writing (review and editing). MTR: Conceptualization, methodology, resources. TH: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation (ToF-SIMS, O-PTIR), writing (review and editing), funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harding, M.A.R., Boyd, A.J., Siljeström, S. et al. Amide groups in 3.7 billion years old liquid inclusions. Sci Rep 14, 23189 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74571-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74571-6