Abstract

There has been an increasing focus on the interplay between physical frailty and cognitive impairment, as both conditions pose significant risks for life-threatening health complications and are receiving considerable attention in global geriatric health initiatives. A recent consensus introduces “cognitive frailty,” denoting the co-existence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment without dementia. This study aims to ascertain the prevalence of cognitive frailty and investigate the factors contributing to gender differentials of cognitive frailty among older adults in India. This study has used the data from the nationally representative survey Longitudinal Ageing Study in India 2017–18. This study included a sample of 13,946 males and 14,989 females aged 60 and above. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted. A proportion test was employed to assess gender disparities and determine the statistical significance of risk factors. Furthermore, multivariate decomposition analysis was performed to identify the extent to which various covariates contribute to explaining the gender differences observed in cognitive frailty. The overall prevalence of cognitive frailty was 4.4%. There was a significant gender difference in cognitive frailty among older adults in India (Difference: 4.3%; p-value < 0.001] with 2.1% (95% CI: 1.8–2.3) older males and 6.4% (95% CI: 6.0-6.8) older females suffering from cognitive frailty. The considerable gender gap in cognitive frailty would be reduced if women had similar levels of education (37% reduction) than men. Results highlight that increasing age, being a woman (AOR: 1.61; 95% CI: 1.33–1.95), out-of-wedlock, less education and non-working status (AOR:2.19; 95% CI: 1.71–2.80) were significantly associated with cognitive frailty. Poor nutritional status, and depression are also prone among the cognitively frail participants. Gender sensitive interventions improving education access for women are crucial. Developing countries like India urgently require a multidimensional approach to ensure appropriate and comprehensive healthcare for the elderly population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing has become a crucial public health concern worldwide1. In India, the population aged 60 years and above numbered 149 million individuals in 2022, constituting approximately 10.5% of the total population. Estimates suggest that by 2050, this demographic will double, with older adults representing 20.8% of the population, totalling an estimated 347 million2. As the population ages, healthcare systems around the world will encounter considerable challenges in preserving the functional independence of older adults. This demographic shift will have significant implications, not only for individuals but also for societies at large3.

Cognitive functioning is determined by the ability to live a purposeful life, remembered skills, language, thought, memory, executive function, orientation, attention and perception4. ‘Cognitive ageing’ refers to the gradual and longitudinal changes in the cognitive functions that occur alongside ageing5. It is important to recognize that cognitive ageing is a natural and lifelong process experienced by every individual6. In contrast, ‘cognitive impairment’ occurs when an individual faces difficulties in remembering, learning new things, concentrating, or making decisions that impact daily life7. Cognitive impairment is often overlooked in older adults, despite being a prevalent and occasionally reversible health issue linked to ageing8. Nonetheless, the deterioration in cognitive abilities among older adults is associated with adverse physical and psychological changes, such as malnutrition, disability, poor quality of life, depression and increased mortality rates6,8,9,10,11,12.

Frailty, often referred to as a ‘geriatric giant’, is also highly associated with several sociodemographic factors13,14, including poor nutrition15,16, insufficient physical activity17, and low psychosocial health18,19. This condition has been demonstrated to correlate with various adverse outcomes, including cognitive impairment, disability, falls, hospitalization, and mortality15,20. It is a transitional stage of life from being physically healthy and independent to a dependent older adult21. In India, the high prevalence of frailty in the elderly population among the older population is well documented22,23,24. Among the six low- and middle-income countries studied (India, Ghana, Russia, China, Mexico, and South Africa), India exhibited the highest prevalence of frailty cases.

Cognitive impairment is one of the major significant concerns for older individuals, with studies consistently identifying it as one of the most feared aspects of ageing25. The International Consensus Panel has proposed that geriatricians acknowledge a newly identified syndrome termed “cognitive frailty”26, which is defined as the coexistence of cognitive impairment and physical frailty without dementia. Epidemiological evidence suggests that the combination of frailty and cognitive impairment may worsen an individual’s vulnerability and influence the subsequent decline in healthy life expectancy27. Cognitive impairment is a key factor in the concept of frailty in the elderly, with both physiological and pathological implications28,29. This decline can lead to neurocognitive disorders and is influenced by various factors, making it a potential marker for cognitive frailty.

Research indicates that although cognitive fragility is relatively low in older individuals, it is nonetheless a substantial issue due to its detrimental effects. Cognitive frailty is associated with increased risks of falls, hospitalization, reduced quality of life, and higher mortality rates30,31. It is a robust predictor of the development of both overall dementia and specifically vascular dementia30. Panza et al. identified several potential neurobiological mechanisms that may contribute to cognitive frailty, including vascular conditions, muscle loss (sarcopenia), metabolic issues, nutritional deficiencies, psychological influences, and inflammatory processes32. As individuals age, the prevalence of cognitive frailty rises due to diminished capacity for daily activities and deterioration in brain function33. Weight loss and vitamin deficiencies can contribute to physical frailty. Research has demonstrated that the incidence of malnutrition is alarmingly high among elderly individuals experiencing cognitive frailty34,35,36. Higher levels of education are linked to slower rates of cognitive impairment as people age37,38. Older adults who experience depression are more likely to develop cognitive frailty39. Research suggests that engaging in moderate physical activities for at least a year can help slow the progression of cognitive frailty in older adults who are sedentary40.

Based on the above-mentioned background, we have developed a conceptual framework that has been summarized in Fig. 1. This conceptual framework presents a comprehensive model for understanding the factors that contribute to cognitive frailty. The framework identifies individual, health, behavioural, and household factors that influence cognitive frailty among older adults, ultimately leading to health outcomes like falls, disability, and death. The model provides a comprehensive theoretical basis for studying the complex interplay of these multifaceted factors in the development of cognitive frailty in older adults.

Prior studies have found a strong connection between cognitive impairment and physical frailty in older adults, as these two conditions often exist together41,42. According to the Fried criteria15, frailty is defined by the presence of at least three out of five specific criteria: unintentional weight loss, slow walking speed, muscle weakness, low physical activity, and exhaustion. Cognitive frailty, therefore, can be viewed as encompassing six components: the five aforementioned frailty criteria and cognitive impairment. These six components reflect various pathophysiological mechanisms of cognitive frailty, and it is important to note that not all older adults diagnosed with cognitive frailty will exhibit the same combination of these components.

Understanding gender differences in cognitive frailty is also essential because men and women may experience aging and cognitive decline differently due to biological, social, and cultural factors. Previous studies have shown that women often have a higher prevalence of both frailty and cognitive impairment compared to men, potentially due to longer life expectancy and differential exposure to risk factors43,44. In India, gender disparities are further influenced by societal norms, access to education, and healthcare utilization. Investigating these differences can provide valuable insights into the specific needs of older adults in India, allowing for the development of gender-sensitive interventions and policies aimed at reducing cognitive frailty and improving overall quality of life.

Thus, It is important to understand how the components of cognitive frailty contribute to disability among older adults, as well as the gender differences in these effects, in order to develop effective interventions that can help delay functional decline in this population. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive investigation into cognitive frailty among the elderly population in India has been undertaken. Thus, the present study aims to assess the prevalence of cognitive frailty and its associated risk factors among older adults in India. The objective of this study also aims to explore the gender differences in cognitive frailty among older adults in India along with exploring the factors contributing to this gender gap.

Materials and methods

Data source

The study utilized data from the of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) wave-1, conducted between April 2017 and December 2018, as part of the Global Health and Retirement Study (HRS). LASI is a large-scale longitudinal survey representative at both national and state levels, focusing on aging and health among individuals aged 45 and above, as well as their spouses regardless of age. It collected comprehensive data on physical and mental health, social security, and economic well-being with the collaboration of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) provided essential guidance and ethical approval for conducting the LASI. Participants were provided with detailed information brochures outlining the objectives, privacy protection measures, and health assessment safety protocols of the survey. In accordance with ethical standards, consent forms were administered to all participants. The survey utilized a multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling approach, employing three-stage sampling designs for rural areas and four-stage designs for urban areas45.

Study sample

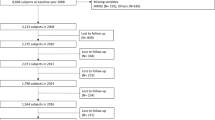

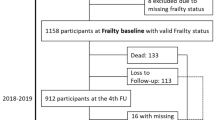

This research utilized de-identified data derived from LASI, wave 1 survey. The total individual sample size 73,396 aged 45 and above and their spouses irrespective of their ages without any missing data in age reporting. Individuals below the age of 60 years were excluded, as the study specially focused on the older adults aged 60 and above. The dependent variable, cognitive frailty in older adults, was measured using anthropometric measurements. Respondents with incomplete anthropometric data were excluded from the analysis. Also, information on any of the other explanatory variables such as working status, religion, caste, self-rated health, etc., consists of missing values, that had been dropped. Hence, a total of 28,935 (13,946 males and 14,989 females) individuals aged 60 and above constituted the analytical sample of our study. Figure 2 provides a detailed flowchart of the sample selection process for this study.

Outcome variable

Assessment of physical frailty

Physical frailty was assessed using the modified Frailty Phenotype Scale15. These components have been considered to prepare the scale:

-

(i)

Weight loss: Unintentional weight loss was evaluated by asking individuals, “Have you experienced weight loss in the last 12 months due to insufficient food in your household?” Those who responded “Yes” were coded as “1” to indicate weight loss, while those who answered “No” were coded as “0.“.

-

(ii)

Exhaustion: Participants were asked two questions derived from the scale of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) regarding their frequency of experiencing feelings of exertion and fatigue over the past week. Responses were coded as “1” for “three or more days” and “0” for “less than three days.“.

-

(iii)

Grip strength: This survey assessed handgrip strength using a handheld Smedley’s Hand Dynamometer. The final grip strength was determined by calculating the average score (in Kg) from two consecutive trials of the dominant hand. Individuals scoring in the bottom quintile were classified as having weak grip strength, which was adjusted for body mass index and gender. Low grip strength was coded as “1” for “yes” and “0” for “no” otherwise.

-

(iv)

Slow Walk time: In LASI, respondents were instructed to walk a distance of 4 m twice at their usual walking pace. The time taken by each individual to complete the walk was recorded in seconds, and the average time (in seconds) was calculated. Individuals in the bottom quintile of time values, adjusted for gender and median height, were categorized as slow walkers. “Yes” was coded as “1” to indicate slow walking, while “No” was coded as “0” for other responses.

-

(v)

Lesser Physical activity: In LASI, individuals were queried about their physical activity with the question, “How often do you engage in sports or vigorous activities, such as going to a health center or gym, swimming, running or jogging, cycling, or performing tasks like heavy lifting, digging with a spade or shovel, farm work, chopping, fast bicycling, or cycling with loads?” Low physical activity was defined as “One to three times a month, hardly ever, or never = 1,” while “once a week or more than once a week = 0” indicated higher activity levels.

Dichotomous variables were established for each of the five components, and a frailty score was computed by summing up all the variables. The frailty score ranges from 0 to 5. Individuals meeting three or more criteria were classified as having physical frailty (PF), while those meeting fewer than three were categorized as non-physically frail (NPF) in this study15.

Assessment of cognitive impairment

Cognitive impairment was evaluated across five main domains: memory (assessed through immediate and delayed word recall), orientation (based on time and place), arithmetic ability (including serial sevens, backward counting, and computation), executive functioning (evaluated with paper folding and pentagon drawing tasks), and object naming. The composite score ranges from 0 to 43, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning. In this study, cognitive impairment (CoI) was identified as scores below the 10th percentile, indicating lower cognitive functioning, while scores above this threshold were categorized as non-cognitive impairment (NCoI)45,46.

Operationalization of cognitive frailty

Cognitive frailty was assessed based on the definition proposed by a consensus panel organized by the International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG) in Toulouse, France on April 16, 201326,47. In this study, cognitive frailty was categorized as the coexistence of both physical frailty (PF) and cognitive impairment (CoI), and others (non-physical frailty and non-cognitive frailty) have been classified as ‘robust’.

Explanatory variables

Main group variable

Gender was categorized as male, female and was considered as the main group variable in the present analysis.

Individual factors

Age was coded as 60–60 years, 70–79 years, and 80 years and above. Education was coded as no education, primary, secondary and above. Working status was coded as working, never worked, earlier worked but currently not working. Marital status was coded as currently in marital union, widowed, and others (divorced/separated/deserted/never married/live in relationship)48. Living arrangement was cod ed as living alone, living with spouse, living with children and spouse, living with children and others, living with others. Social participation was assessed with the question, “Do you belong to any organizations, religious groups, clubs, or societies?” Responses were coded as either yes or no.

Health factors

Self-rated health was categorized as good, including responses of excellent, very good, and good, while poor encompassed fair and poor ratings. Depression was evaluated utilizing the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), employing a four-point scale. Participants were asked ten questions about their experiences over the past week, covering topics such as trouble concentrating, feeling depressed, low energy, fearfulness, loneliness, bothersome thoughts, and feelings of exertion. The scale included seven items related to negative symptoms and three items related to positive symptoms. For negative symptoms, a score of ‘0’ was assigned to responses indicating “rarely or never (< 1 day)” or “sometimes (1 or 2 days)”, while higher categories were coded as ‘1’. Conversely, for positive symptoms, this scoring was reversed. The composite score of Depression scale ranges from 0 to 10. Respondent with a score of four or more was coded as yes (have depression symptoms) and less than four coded as no49,50.

Nutritional status measured utilized the body mass index (BMI), and classification of BMI follows as underweight (below 18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), and overweight (25 and above)51. Presence of chronic disease was coded as 0 “no chronic disease”, 1 “any one chronic disease”, and 2+ “presence of 2 or more chronic diseases or multimorbidity”52. Chronic pain was categorized as yes and no. History of fall status was coded and yes and no.

Behavioural factors

Tobacco consumption used the question “ever smoked or used smokeless tobacco?” and response was coded as yes and no. Alcohol consumption was assessed by asking the question, “Have you ever consumed any alcoholic beverages?“, and the responses were coded as either yes or no. Physical activity was assessed using two questions from the LASI survey. It was categorized into four levels: “never” (hardly ever or never engaged), “light” (one to three times a month), “moderate” (engaged in moderate activities every day, more than once a week, or once a week), and “vigorous” (engaged in vigorous activities every day, more than once a week, or once a week).

Household factors

Using the consumption expenditure data of the household, the monthly per-capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile had been calculated. The sample household were canvassed using 11 and 29 questions on food and non-food expenditures respectively. Food spending data was gathered for last seven days, and for non-food items expenses was collected for last 30 days to the survey date. The monthly per-capita consumption expenditure is measured and mostly utilized to summaries consumptions by the sampled households. The continuous variable was then classified into five quintiles i.e., poorest, poorer middle richer richest. Religion was categorized into three groups: Hindu, Muslim, and Others. Caste was classified into four groups: Scheduled Tribes (ST), Scheduled Castes (SC), Other Backward Class (OBC), and None of them. SC and ST groups are among the most disadvantaged and discriminated socio-economic groups in India. Regions were coded as North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South. Place of residence was coded as rural ‘0’ and urban ‘1’.

Statistical analysis

In this study we used univariate statistical analysis to report the descriptive statistic of the study population. To estimate the observed prevalence of cognitive frailty by individual, health and behavioral and household factors, the bivariate analysis was carried out. A proportion test was used to evaluate the gender differentials and the level of significance53. Further, multivariate logistic regression analysis utilized to determine the factors for cognitive frailty among older adults within a multivariate framework. The standard equation of logistic regression model is as follows:

Here in this equation, Pi denotes the probability that the ith individual suffers from cognitive frailty. The statistical analysis was conducted on a sample adhering to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The analyses utilized a complete case analysis method, considering the selected variables, and the calculations were adjusted to accommodate survey weights. The estimates were presented in an unadjusted (uOR) only for the main grouped variable and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). In this study, the odds ratio of greater than 1 for a particular category of the explanatory variable indicates higher odds of cognitive frailty given the effect for all other explanatory variables remain constant.

A multivariate decomposition analysis was employed to discern the contributions of covariates in elucidating the variations among groups in average predictions54. The focus of the decomposition analysis was to find variables that influence the difference in cognitive frailty between male and female.

In multivariate decomposition analysis, two contributing effects are identified: compositional differences (endowments), denoted as ‘E’, and the effects of characteristics, which represent differences in coefficients or behavioural responses ‘C’ for the selected explanatory variables55. The observed disparities in cognitive frailty can be decomposed into two components: characteristics (or endowments) and coefficients (or effects of characteristics), thereby gaining a deeper understanding of the underlying factors56. In the non-linear model, the dependent variable is a function of a linear combination of predictors and regression coefficients:

where Y denotes the n*1 dependent variable vector, X an n*K matrix of independent variables, and a K*1 vector of coefficients.

The proportion difference in Y between male A and female B of cognitive frailty can be decomposed as:

For the log odds of cognitive frailty, the proportion of the model is written as

The component ‘E’ represents the difference attributed to changes in endowment, typically referred to as the explained component. Conversely, the ‘C’ component signifies the difference attributed to changes in coefficients (behavioral), often termed the unexplained component (Table 1).

Three decomposition models were constructed. The first decomposition considered work, economic factors and educational attainment; the second decomposition took socio-demographic characteristics into account along with the first model; the third decomposition included health-related factors such as self-rated health, and chronic conditions, in addition to the factors considered in the second decomposition. Additionally, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was applied for post-estimation of the adjusted logistic regression model to assess the model’s goodness-of-fit. All the analysis were carried out using Stata version 17 and Microsoft Excel.

Ethics approval

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Central Ethics Committee on Human Research (CECHR) provided the requisite guidance, guidelines, and ethics approval for the implementation of the LASI survey. All methodologies employed in this survey adhered strictly to these pertinent guidelines.

Consent to participate

The survey agencies responsible for conducting the field survey for data collection obtained prior informed consent, both signed and oral, from eligible respondents for both interviews and biomarker tests, in accordance with Human Subjects Protection protocols. All participants received detailed explanations regarding the purposes of the study.

Results

Background characteristics of the study population

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the study population by gender. A sample of 28,935 older adults aged 60 and above surveyed across India is analyzed in the study. About 13,946 (48%) males and 14,989 (52%) females were included in the analysis. A higher proportion of older adults belonged to the young-old cohort. More than half of the older adults had no education or primary not completed. However, it was higher among older females (72.6%) than older males (38.8%). Nearly 44% of older males and one-fifth of older females were working. About 3% of older males and 9% of older females were living alone, and around 6% of older males and 4% of older females were engaged in social participation. Among the respondents 46% if older males and half of older females reported poor self-rated health. While 35% of males never engaged in physical activity, the same was lower in older females (30% never engaged in physical activity). Moreover, depression was more prevalent among older females (32%) compared to the older male. Nearly one-fourth of older adults in the study population experienced multimorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic diseases. Additionally, 28% of older adults belonged to SC and ST caste groups. The majority of study participants were Hindu (82.5%) and belonged to rural areas (73.4%).

Prevalence of cognitive frailty among older male and female in India

Table 3 depicts the bivariate distribution of male and female older adults with cognitive frailty by selected explanatory. Overall, the prevalence of cognitive frailty was significantly higher among older females (6.4%; CI: 6.0-6.8) than males (2.1%; CI: 1.8–2.3) (p < 0.001). A higher proportion of older females had developed cognitive frailty across all age groups than their male counterparts. Females with no education had a much higher prevalence (8.3%; CI: 7.8–8.9) compared to males (4.3%; CI: 3.7–4.9). Cognitive frailty was lowest among those with secondary and higher education for both genders, but females still showed a slight advantage in this group. Females who had never worked (5.6%; CI: 5.1–6.2) or were not currently working (9.4%; CI: 8.5–10.2) had a higher prevalence of cognitive frailty than males in similar circumstances. Widowed females (9.1%; CI: 8.4–9.8) were also more affected than widowed males (3.7%; CI:2.9–4.5). Older females living alone (7.3%, CI: 5.8–8.9) or with others (13.8%; CI: 11.7–15.9) had notably higher prevalence of cognitive frailty than males. Cognitive frailty rates among females were higher in rural areas (7.5%; CI: 7.0-8.1) compared to urban areas (3.7%; CI: 3.2–4.3), showing a greater disparity than observed in males. Coming to the poorest quintile household, we observed that 9.4% of older females suffered from cognitive frailty compared to 3.3% among males.

Cognitive frailty across states of India

Nationally, about 4.37% of the older adults reported cognitive frailty. Older adults in the state of Arunachal Pradesh (9.4%) had the highest percentage of cognitive frailty, followed by West Bengal (8.6%). Gendered differences were observed in terms of cognitive frailty across states. For instance, one in ten females suffered from cognitive frailty, whereas the prevalence among males was around 1.3%. The gender gap in cognitive frailty was higher in West Bengal (8.1% difference), followed by Lakshadweep (7.6%) and Uttar Pradesh (7.1%). Among the northeastern states Manipur, Nagaland and Mizoram reported a lower prevalence of cognitive frailty than the national average. In the state of Kerala, home to the highest percentage of older adults aged 60 years and above in India57, around 2.4% of all older adults developed cognitive frailty, and this was higher among females (Appendix Figure S1).

Likelihood of cognitive frailty among Indian older adults aged 60 and above

Table 4 presents the logistic regression estimates for cognitive frailty among older adults in India. As mentioned earlier, the odds ratio of greater than 1 for a given category of the explanatory variable denotes higher odds of cognitive frailty, given effect of all other independent variables remains constant. We found that older females had higher odds [AOR: 1.61; CI: 1.33,1.95] of cognitive frailty than older males in the study. Moreover, Oldest-old adults [AOR: 3.08; CI: 2.55,3.71] had higher odds of cognitive frailty compared to young-old adults. Among older adults who never worked [AOR:2.19; CI: 1.71,2.80] had the higher likelihood to suffer from cognitive frailty than who were working. Older adults who attended secondary and above years of schooling were at lower risk [AOR:0.14; CI: 0.09,0.20] of suffering from cognitive frailty compared to those who never attended school. Older adults living with their children and spouse had significantly lower odds [AOR: 0.64, CI: 0.29,1.43] of cognitive frailty than older adults living alone. Older adults who reported poor self-rated health had higher odds [AOR: 1.74; CI: 1.50,2.02] than their counterparts. Underweight older adults have a higher likelihood of cognitive frailty (AOR:2.01; CI:1.77,2.28), while overweight individuals are less likely to experience it (AOR:0.53; CI:0.44,0.64) compared to those with normal weight. Older adults engaged in moderate level of physical activity in their regular life [AOR:0.52; CI:0.45,0.61] had a lower chance to suffer from those who never engaged in physical activity. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for the logistic regression model produced a chi-square value of 13.86 with a p-value of 0.0854, indicating a good fit to the data and supporting the validity of the results.

Adjusted for control variables, age, education, nutrition and wealth status by gender-classified marginal probabilities were also estimated for cognitive frailty incidence among older adults and were shown in Appendix Figure S2. It became evident that older females exhibited a greater susceptibility to cognitive frailty compared to older males across various age brackets. Estimates revealed that as years of educational attainment increased, the likelihood of older females developing cognitive frailty decreased significantly, falling below that of older males. Additionally, improvements in nutritional status resulted in a reduction in the risk of cognitive frailty for both male and female older adults.

Contributing factors in explaining gender differential in cognitive frailty

Table 5 shows results from three different decomposition models. Model 1, the education, work and economic model, shows that differences in endowments explain about 39% of the gender gap in the prevalence of cognitive frailty among older adults. Educational attainment made a large contribution to differences in cognitive frailty among both males and females (36.1%). Model 2, considering education, work and economic and socio-demographic factors together, suggests that nearly 45% of the gender gap in cognitive frailty in due to differences in those characteristics. Overall, sociodemographic factors contributed to around 12% (of 45.4%) of the gender differential in cognitive frailty among older adults. As we shifted from Model 1 to Model 2, the contribution of educational attainment in differences in cognitive frailty decreased from 36 to 33.4% (see Appendix Table S1). While in Model 3, in which health-related and behavioral factors were added to the factors in Model 2, the total endowment effect increased to 66.4%, largely reducing the “unexplained” contribution (33.6%). Overall, health-related and behavioral factors contributed to around 20.1% of the gender differential in cognitive frailty (Model 3). The contribution of educational attainment to cognitive frailty again drops to 26.3%. However, the negative coefficient shows that if males had the same distribution of education attainment as females, the gender gap in the cognitive frailty would increase. The results of the full decomposition model are presented in Appendix Table S1.

Discussion

Cognitive frailty is one of the most significant and emerging concerns in the study of geriatric healthcare. Older adults experiencing the coexistence of physical frailty and cognitive impairments necessitate mandatory care and significant time from family members to uphold their quality of life31,58,59. Based on the definition by Kelaiditi et al. (2013), this study identified 2.1% of older males and 6.4% of older females had cognitive frailty. Multiple studies have utilized and operationalized diverse definitions, revealing the prevalence of cognitive frailty to range between 1% and 12% among participants60,61. Hence, comparing the current findings with existing studies proves to be challenging. The main findings of this study were that (1) increased age, being female, out-of-wedlock and lower educational status; (2) being the underweight and poor self-rated health status; and (3) depression may increase the risk of cognitive frailty among the older adults. These novel findings enable a comprehensive understanding of a holistic relationship between individual, socio-demographic, health determinants, as well as behavioral characteristics, with cognitive frailty.

Significantly, our data revealed notable gender differences, with older women exhibiting a higher prevalence of cognitive frailty compared to older males. This observation is consistent with certain prior studies indicating that women tend to have a greater coexistence of cognitive impairment and physical frailty62,63. This result was consistent with prior studies, signifying that women have higher morbidity than men due to acute and chronic physical and psychological disorders, and even after eliminating factors associated with reproduction, the discrepancies in morbidity persisted64,65,66. Moreover, the evaluation of functional health, encompassing assessments of difficulties in performing activities of daily living like eating, dressing, bathing, and using the restroom, revealed notable advantages for males than females67,68. Likewise, in line with previous research, our study indicates that older females experience a greater impact from physical restrictions, such as difficulties in activities in daily living and instrumental activities compared to male counterparts. The better cognitive functioning observed in men compared to women could underlie numerous healthier lifestyle choices, potentially leading to reduced vulnerability to cognitive frailty in older males compared to their women counterparts69,70,71. Additionally, due to higher widowhood rates, social isolation and loneliness among older females are considered the most concerning issue in geriatric studies72,73. Several explanations have been documented on the gender variations in cognitive frailty. For example, women are more likely to develop arthritis, osteoporosis, related fractures and depression. all of which can detrimentally impact both mental and physical health66,74,75. On the other hand, females typically have a greater life-expectancy compared to males, which increase their susceptibility to experiencing diminished health status during their later ages63.

There are well-established recommendations supported by robust evidence indicating that both physical frailty syndrome76 and cognitive impairment12 exhibit a significant correlation with advancing age. The current study sheds light on the importance of age as a substantial predictor of cognitive frailty. As such, it underscores the critical need for early screening, assessment, and intervention for cognitive frailty among older individuals. By addressing cognitive frailty in its early stages, interventions can be implemented to alleviate the risk of future disability and other adverse outcomes, ultimately promoting healthier aging trajectories.

The findings from this study show that the incidence of cognitive frailty was higher among those with no formal education than those with higher education, which was in line with some previous studies30. Also, it was noticed that providing equalizing access to education would reduce gender gaps in cognitive frailty by almost 37%. Prior studies indicate that higher education can enhance cognitive abilities among older individuals77,78. The association between education and cognitive frailty could be affected by various pathways. The brain reserve capacity theory specifies that well-educated people probably have greater brain reserve capacity than their counterparts which might be associated with better cognition ability in educated people 79. Moreover, educated individuals may be more inclined to seek emotional support compared to their less educated counterparts, which can contribute to positive changes in brain structure and function, further enhancing cognitive abilities80. Education consistently serves as a vital instrument for enhancing public health and well-being, as it fosters awareness and alleviating the burden on healthcare systems81. Highly educated people may follow healthy lifestyles linked to better cognition82.

Marital status and working status are also critical individual factors associated with human health and longevity. Our study reported that out-of-wedlock (single, divorced, separated and/or widowed) were more likely to experience cognitive frailty than those were currently in the marital union, and a significant association of physical frailty syndrome and cognitive impairment with marital status83,84. The results indicated that individuals who were employed exhibited a lower prevalence of cognitive frailty compared to those who were unemployed. Consistent with prior research, this finding aligns with studies demonstrating that employment status correlates with enhanced cognitive functions and reduced frailty risks85,86.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, this study utilized cross-sectional data, which could only determine association and not causation and effect. A few of the important predictors were self-reported, such as self-rated health. Self-reporting of the data of chronic conditions and health issues could have been affected by recall bias87. Secondly, LASI survey excluded individuals who were institutionalized or bedridden, who may have cognitive impairment and heightened vulnerability to cognitive frailty. Despite a few limitations, the study has some considerable strengths too. The study’s strengths included the use of a large population-based dataset, repeated measures, and the use of validated questionnaires to assess both frailty and cognitive functions among older adults. Another strength of the study is the assessment of cognitive frailty differentials between older men and women. This finding may hold significant medical implications for preventing and reversing cognitive frailty in older Indian adults.

Conclusion

This study contributes to a better understanding of cognitive frailty among older adults in India. The results found that equalizing access to education and work would reduce gender gaps in cognitive frailty by almost 37%. Concluding remarks support the hypothesis that the female gender is positively associated with higher prevalence of coexisting physical frailty and cognitive impairments88. Therefore, addressing gender-related inequalities in education and work status shall be promoted. Gender sensitive interventions improving education access among the female gender would bring relevant and desired results. There is a need to develop interventions focusing on building an informal support group at the community level for widows. Based on evidence from this study it seems that preventing cognitive frailty in the older adults may also be accomplished by addressing lifestyle risk factors, such as improving physical activity and social participation among them. Additionally, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of cognitive frailty and provides direction for future research. Prospective studies should focus on community-based early intervention strategies to integrate physical and cognitive functions for older adults.

Data availability

The datasets used in the study are publicly available and the data request can be put through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities in daily living

- CoI:

-

Cognitive impairment

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities in daily living

- LASI:

-

Longitudinal Ageing Study in India

- MoHFW:

-

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

- MPCE:

-

Monthly per capita consumption expenditure

- NPF:

-

Non-physical frailty

- NCoI:

-

Non-cognitive impairment

- PF:

-

Physical frailty

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3. (2022).

International Institute for Population Sciences, United Nations Population Fund. India Ageing Report 2023, Caring for Our Elders: Institutional Responses [Internet]. New Delhi, India: United Nations Population Fund; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/20230926_india_ageing_report_2023_web_version_.pdf

Wang, C., Zhang, J., Hu, C. & Wang, Y. Prevalence and risk factors for cognitive frailty in aging hypertensive patients in China. Brain Sci. 11(8), 1018 (2021).

Sugar, J., Riekse, R. J., Holstege, H. & Faber, M. A. Introduction to Aging: A Positive, Interdisciplinary Approach (Springer, 2014).

Karlawish, J. & Powell, T. Definition of cognitive aging. Gerontologist 55(2), 176 (2015).

Obisesan, T. O. & Gillum, R. Cognitive function, social integration and mortality in a U.S. national cohort study of older adults. BMC Geriatr. 9(1), 33 (2009).

CDC. Cognitive impairment: the impact on health in Iowa; 2011 [Internet]. United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/cognitive_impairment/cogimp_ia_final.pdf

Si, T., Xing, G. & Han, Y. Subjective cognitive decline and related cognitive deficits. Front. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00247 (2020).

Fick, D. M. Promoting cognitive health: Some good news and a brief summary of the institute of medicine report cognitive aging: Progress in understanding and opportunities for action. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 42(7), 4–6 (2016).

Hill, N. L. et al. Subjective cognitive impairment and quality of life: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 29(12), 1965–1977 (2017).

Esteban-Cornejo, I. et al. Cognitive frailty and mortality in a national cohort of older adults: The role of physical activity. Mayo Clin. Proc. 94(7), 1180–1189 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling Chinese populations aged over 55 years: A meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 21(1), 10 (2021).

Szanton, S. L., Seplaki, C. L., Thorpe, R. J., Allen, J. K. & Fried, L. P. Socioeconomic status is associated with frailty: The women’s health and aging studies. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 64(01), 63–67 (2010).

Gu, D., Yang, F. & Sautter, J. Socioeconomic status as a moderator between frailty and mortality at old ages. BMC Geriatr. 16(1), 151 (2016).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 56(3), M146-156 (2001).

Walston, J., Buta, B. & Xue, Q. L. Frailty screening and interventions: Considerations for clinical practice. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 34(1), 25–38 (2018).

Tribess, S., Virtuoso Júnior, J. S. & de Oliveira, R. J. Physical activity as a predictor of absence of frailty in the elderly. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 58(3), 341–347 (2012).

Mhaoláin, A. M. N. et al. Frailty, depression, and anxiety in later life. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24(8), 1265–1274 (2012).

Desrichard, O., Vallet, F., Agrigoroaei, S., Fagot, D. & Spini, D. Frailty in aging and its influence on perceived stress exposure and stress-related symptoms: Evidence from the Swiss Vivre/Leben/Vivere study. Eur. J. Ageing 15(4), 331–338 (2018).

Sacha, J., Sacha, M., Soboń, J., Borysiuk, Z. & Feusette, P. Is it time to begin a public campaign concerning frailty and pre-frailty? A review article. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00484 (2017).

Fillit, H. & Butler, R. N. The frailty identity crisis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57(2), 348–352 (2009).

Das, S. & Chandel, S. Frailty pattern among the elderly rural women of India (2018).

Dasgupta, A. et al. How frail are our elderly? An assessment with Tilburg frailty indicator (TFI) in a rural elderly population of West Bengal. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 8(7), 2242–2248 (2019).

Kendhapedi, K. K. & Devasenapathy, N. Prevalence and factors associated with frailty among community-dwelling older people in rural Thanjavur district of South India: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9(10), e032904 (2019).

Murman, D. L. The impact of age on cognition. Semin. Hear. 36(3), 111–121 (2015).

Kelaiditi, E. et al. Cognitive frailty: Rational and definition from an. J. Nutr. Health Aging 17(9), 726–734 (2013).

Alencar, M. A., Dias, J. M. D., Figueiredo, L. C. & Dias, R. C. Frailty and cognitive impairment among community-dwelling elderly. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 71(6), 362–367 (2013).

Brigola, A. G. et al. Relationship between cognition and frailty in elderly: A systematic review. Dement. Neuropsychol. 9(2), 110–119 (2015).

Krolak-Salmon, P. Cognition et fragilité chez la personne âgée. cah année gerontol 4(1), 13–16 (2012).

Solfrizzi, V. et al. Reversible cognitive frailty, dementia, and all-cause mortality. The Italian longitudinal study on aging. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18(1), 89–89 (2017).

Rivan, N. F. M. et al. Cognitive frailty is a robust predictor of falls, injuries, and disability among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 25(21), 593 (2021).

Panza, F. et al. Different cognitive frailty models and health- and cognitive-related outcomes in older age: From epidemiology to prevention. J. Alzheimers Dis. 62(3), 993–1012 (2018).

Rivan, N. F. M. et al. Cognitive frailty among Malaysian older adults: Baseline findings from the LRGS TUA cohort study. CIA 25(14), 1343–1352 (2019).

Chye, L. et al. Strong relationship between malnutrition and cognitive frailty in the Singapore longitudinal ageing studies (SLAS-1 and SLAS-2). J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 5(2), 142–148 (2018).

Dominguez, L. J. & Barbagallo, M. The relevance of nutrition for the concept of cognitive frailty. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 20(1), 61 (2017).

Seesen, M., Sirikul, W., Ruangsuriya, J., Griffiths, J. & Siviroj, P. Cognitive frailty in Thai community-dwelling elderly: Prevalence and its association with malnutrition. Nutrients 13(12), 4239 (2021).

Brigola, A. G. et al. Limited formal education is strongly associated with lower cognitive status, functional disability and frailty status in older adults. Dement. Neuropsychol. 13, 216–224 (2019).

Zahodne, L. B., Stern, Y. & Manly, J. J. Differing effects of education on cognitive decline in diverse elders with low versus high educational attainment. Neuropsychology 29(4), 649–657 (2015).

Kwan, R. Y. C. et al. Cognitive frailty and its association with nutrition and depression in community-dwelling older people. J. Nutr. Health Aging 23(10), 943–948 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Effect of 24-month physical activity on cognitive frailty and the role of inflammation: the LIFE randomized clinical trial. BMC Med. 16(1), 185 (2018).

Shimada, H. et al. Combined prevalence of frailty and mild cognitive impairment in a population of elderly Japanese people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 14(7), 518–524 (2013).

Robertson, D. A., Savva, G. M. & Kenny, R. A. Frailty and cognitive impairment: A review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 12(4), 840–851 (2013).

Mielke, N., Schneider, A., Huscher, D., Ebert, N. & Schaeffner, E. Gender differences in frailty transition and its prediction in community-dwelling old adults. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7341 (2022).

Park, C. & Ko, F. C. The science of frailty: Sex differences. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 37(4), 625–638 (2021).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), The University of, Southern California (USC). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017–18, India Report [Internet]. Mumbai, India; 2020. Available from https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_compressed.pdf.

Pandav, R., Fillenbaum, G., Ratcliff, G., Dodge, H. & Ganguli, M. Sensitivity and specificity of cognitive and functional screening instruments for dementia: The Indo-US dementia epidemiology study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50(3), 554–61 (2002).

Ruan, Q. et al. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing Res. Rev. 1(20), 1–10 (2015).

Aditi, S., Singh, S. K., Jaiswal, A. K. & Verma, M. Is there a ubiquitous association between sleep disorder and frailty? Findings from LASI (2017–18). BMC Geriatr. 23(1), 429 (2023).

Pengpid, S. & Peltzer, K. Utilization of complementary and traditional medicine practitioners among middle-aged and older adults in India: results of a national survey in 2017–2018. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 15(21), 262 (2021).

Kumar, S., Nakulan, A., Thoppil, S. P., Parassery, R. P. & Kunnukattil, S. S. Screening for depression among community-dwelling elders: Usefulness of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 38(5), 483–485 (2016).

Khan, J., Chattopadhyay, A. & Shaw, S. Assessment of nutritional status using anthropometric index among older adult and elderly population in India. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 13015 (2023).

Keetile, M., Navaneetham, K. & Letamo, G. Prevalence and correlates of multimorbidity among adults in Botswana: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 15(9), e0239334 (2020).

Fan,C., Wang, L. & Wei, L Comparing two tests for two rates: The American statistician. 71(3) Get Access [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2016.1246263

Powers, D., Yoshioka, H. & Yun, M. S. mvdcmp: Multivariate decomposition for nonlinear response models. Stata J. 11(4), 556–576 (2011).

Tiruneh, S. A., Lakew, A. M., Yigizaw, S. T., Sisay, M. M. & Tessema, Z. T. Trends and determinants of home delivery in Ethiopia: Further multivariate decomposition analysis of 2005–2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Surveys. BMJ Open 10(9), e034786 (2020).

Debie, A., Lakew, A. M., Tamirat, K. S., Amare, G. & Tesema, G. A. Complete vaccination service utilization inequalities among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: A multivariate decomposition analyses. Int. J. Equity Health 19(1), 65 (2020).

Registrar General of India. Census of India, 2011: Provisional population tables (Government of India, 2011).

Verma, M., Grover, S., Singh, T., Dahiya, N. & Nehra, R. Screening for cognitive impairment among the elderly attending the noncommunicable diseases clinics in a rural area of Punjab, North India. Asian J. Psychiatr. 50, 102001 (2020).

Miyamura, K. et al. Frailty syndrome and cognitive impairment in older adults: Systematic review of the literature. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 27, e3202 (2019).

Sugimoto, T. et al. Epidemiological and clinical significance of cognitive frailty: A mini review. Ageing Res. Rev. 1(44), 1–7 (2018).

Vatanabe, I. P. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on cognitive frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Risk and associated factors. Aging Ment. Health 26(3), 464–476 (2022).

Das, S. Cognitive frailty among community-dwelling rural elderly population of West Bengal in India. Asian J. Psychiatr. 70, 103025 (2022).

Hubbard, R. E. Sex differences in frailty. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. Geriatr. 41, 41–53 (2015).

Boerma, T., Hosseinpoor, A. R., Verdes, E. & Chatterji, S. A global assessment of the gender gap in self-reported health with survey data from 59 countries. BMC Public Health 16(1), 675 (2016).

Nathanson, C. A. Illness and the feminine role: A theoretical review. Soc. Sci. Med. (1967) 9(2), 57–62 (1975).

Waldron, I. Sex differences in illness incidence, prognosis and mortality: Issues and evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 17(16), 1107–1123 (1983).

Alexandre, TdaS. et al. Gender differences in incidence and determinants of disability in activities of daily living among elderly individuals: SABE study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 55(2), 431–437 (2012).

Al Hazzouri, Z. A., Sibai, A. M., Chaaya, M., Mahfoud, Z. & Yount, K. M. Gender differences in physical disability among older adults in underprivileged communities in Lebanon. J. Aging Health 23(2), 367–382 (2010).

Mohan, D., Iype, T., Varghese, S., Usha, A. & Mohan, M. A cross-sectional study to assess prevalence and factors associated with mild cognitive impairment among older adults in an urban area of Kerala, South India. BMJ Open 9(3), e025473 (2019).

Lee, Y. & Shinkai, S. Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea and Japan. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20(6), 576–586 (2005).

Sharma, M. & Pradhan, M. R. Socioeconomic inequality in cognitive impairment among India’s older adults and its determinants: A decomposition analysis. BMC Geriatr. 23(1), 7 (2023).

Cohen-Mansfield, J. & Parpura-Gill, A. Loneliness in older persons: A theoretical model and empirical findings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 19(2), 279–294 (2007).

Hawkley, L. C., Burleson, M. H., Berntson, G. G. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85(1), 105–120 (2003).

Dhak, B. & Mutharayappa, R. Gender differential in disease burden: Its role to explain gender differential in mortality. Working Papers [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2024 Feb 20]; Available from https://ideas.repec.org//p/sch/wpaper/221.html

Joshi, R. et al. Chronic diseases now a leading cause of death in rural India—Mortality data from the Andhra Pradesh Rural Health Initiative. Int. J. Epidemiol. 35(6), 1522–1529 (2006).

Hanlon, P. et al. Frailty measurement, prevalence, incidence, and clinical implications in people with diabetes: A systematic review and study-level meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 1(3), e106–e116 (2020).

Wilson, R. S. et al. Educational attainment and cognitive decline in old age. Neurology 72(5), 460–5 (2009).

Wu, F. et al. Social-economic status and cognitive performance among Chinese aged 50 years and older. PLOS One 11(11), e0166986 (2016).

Schmand, B., Smit, J. H., Geerlings, M. I. & Lindeboom, J. The effects of intelligence and education on the development of dementia. A test of the brain reserve hypothesis. Psychol. Med. 27(6), 1337–1344 (1997).

Beydoun, M. A. et al. Serum nutritional biomarkers and their associations with sleep among US Adults in recent national surveys. PLOS One 9(8), e103490 (2014).

Hahn, R. A. & Truman, B. I. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int. J. Health Serv. 45(4), 657–678 (2015).

Nutakor, J. A. et al. Association between socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning among older adults in Ghana. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36(5), 756–765 (2021).

Feng, L. et al. Marital status and cognitive impairment among community-dwelling Chinese older adults: The role of gender and social engagement. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 4(3), 375–384 (2014).

Biritwum, R. B. et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with frailty and disability in older adults from China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa. Maturitas 1(91), 8–18 (2016).

Van Der Linden, B. W. A. et al. Life-course circumstances and frailty in old age within different european welfare regimes: A longitudinal study with SHARE. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 75(6), 1326–1335 (2020).

Muhammad, T., Govindu, M. & Srivastava, S. Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 21(1), 85 (2021).

Jager, K. J. et al. Where to look for the most frequent biases?. Nephrology (Carlton) 25(6), 435–441 (2020).

Ma, L., Zhang, L., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Tang, Z. & Chan, P. Cognitive frailty in China: Results from China comprehensive geriatric assessment study. Front. Med. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 21]; 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00174 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and A.A. contributed to the conception and design of the study. M.S. conducted the analysis and I.G. and A.C. wrote the first draft. A.C. critically revised and supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors made contributions to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study does not involve the collection of information from subjects. Consent to participate is not applicable since the study is a secondary data analysis based on LASI data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, M., Anand, A., Chattopadhyay, A. et al. Gender differentials in cognitive frailty among older adults in India: a multivariate decomposition approach. Sci Rep 14, 24597 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74584-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74584-1