Abstract

In recent years, industrial gas flow has been obtained from the bauxite gas reservoir in the southwestern Ordos Basin, which has made the identification of aluminium-bearing rock reservoirs a popular topic. To accelerate the exploration and development of this type of gas reservoir, major element testing, rock thin section identification and principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted, and a method for rapid and accurate identification of bauxite reservoirs via conventional logging was established. The test results clearly revealed the vertical stratification of major elements and three lithologies in the aluminium (Al)-bearing rock series in the study area. The log response characteristics of effective gas reservoirs were summarized, providing a basis for subsequent research on identifying effective bauxite reservoirs via mathematical dimensionality reduction of logging curves. The porosity comparison of strata with different lithologies suggests that dissolution pores are more developed in Al-rich layers, providing insight for identifying effective reservoirs by Al2O3 content. On the basis of the above findings, a lithological identification chart of Al-bearing rock series was established via principal component analysis (PCA), and an effective bauxite reservoir logging identification model based on Al2O3 content prediction was developed. The results show that using the dimensionality reduction method for principal component analysis of logging curves with overlapping information can avoid model distortion caused by multicollinearity. The research results can be used to identify bauxite reservoirs quickly and accurately without other test data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breakthroughs have recently been made in natural gas exploration of bauxite on the southern margin of the Ordos Basin1,2; these breakthroughs have greatly expanded the field of natural gas exploration and demonstrated the potential of large-scale reserves and broad exploration prospects of bauxite. In the past, because of their wide distribution, poor physical properties and strong capping ability, aluminium (Al)-bearing rocks and dark mudstone deposited in the transitional facies of the late Palaeozoic sea and land were regarded as the direct cap of the lower Palaeozoic weathering crust gas reservoir in the Ordos Basin3,4,5. The industrial breakthrough of bauxite, as a new type of natural gas reservoir, has fundamentally changed the traditional geological understanding that Al-bearing rock can only cap and cannot form an effective reservoir. Presently, the identification of gas reservoirs is becoming a popular topic of study in the efficient exploration and development of bauxite series.

At present, in the absence of coring, geophysical logging is usually used to identify effective reservoirs6,7. Conventional log intersection and superposition charts are considered the broadest and most low-cost methods for log-based reservoir identification8,9. However, this approach has limitations and challenges for bauxite reservoirs. The sedimentary and diagenetic processes of bauxite reservoirs exhibit significant complexity10, resulting in a more intricate rock composition, strong heterogeneity, and substantial interference and overlapping log information. First, bauxite may contain a variety of mineral components with varying contents such as hydrodiaspore, diaspore, anatase, haematite, siderite, kaolinite, illite, etc.11,12,13. The response characteristics of these minerals on the log differ significantly, contributing to the complexity of the bauxite rock response. Second, the development of bauxite reservoirs may entail the superposition and alternation of multiple diagenetic stages14, leading to considerable vertical and lateral heterogeneity in Al-bearing rock sequences, encompassing lithological variations and porosity fluctuations. In particular, abrupt lithological changes vertically result in overlapping logging responses, thereby increasing the complexity of lithological identification. Owing to the presence of multiple solutions for log responses and potential overlap in response characteristics, a single type of log response may correspond to various geological phenomena or rock types. Additionally, distinct rock types and pore structures may also exhibit similar response characteristics on the log curve. For example, in conventional clastic rock logs, a high clay content in nonreservoir strata can lead to increased natural gamma-rays as well as heightened density but reduced resistivity15,16. However, within Al-bearing rocks, a mudstone section with high contents of heavy minerals and potassium at the bottom of an aluminous formation can show the same response characteristics as a bauxite gas reservoir. If the conventional intersection diagram is used directly, the mudstone at the bottom is often mistaken as an effective reservoir, which is unfavourable for the exploration and development of bauxite gas reservoirs.

As a mathematical statistical method, principal component analysis (PCA) can reduce the dimension and concentrate the stratum geophysical information while largely maintaining the original information17,18,19. Since the 1980s, Schlumberger has researched the use of well log data for automated electrofacies zoning of wells through PCA, facilitating geological sequence determination, reservoir zonation, and well-to-well correlation20. PCA has been widely used in well logging identification and evaluation of oil and gas reservoirs in recent years. According to the characteristics of the diverse lithology and complex components of glutenite in Dongying hollow, Gao and Li established a lithological recognition method and porosity evaluation model for tight sandstone based on PCA, which successfully improved the accuracy of porosity logging evaluations of a tight glutenite reservoir21. Jahan et al. successfully identified different fault patterns in the Upper, Middle, and Lower Bakken members and the Three Forks Formation by integrating multiple attributes of seismic data through PCA. The results of fault cuts correlated well with those from missing well log Sect22. Karimi et al. used PCA to identify a carbonate reservoir in the Middle East and extended an automatic well-to-well correlation approach, and noted that PCA is beneficial for increasing well-to-well correlation accuracy by reducing the dependency of well-to-well correlation parameters and feature extraction from log data23. Li et al. reconstructed missing essential neutron and sonic logs from coal seam logs via coalbed methane well logging (density, resistivity, gamma ray, spontaneous potential, and calliper logs) via PCA and compared them with empirical methods, neural network models, and multivariate regression methods24. The results revealed that the key logging curves reconstructed based on PCA were more reliable in evaluating the coalbed methane content. In view of the failure of fracture characterization and classification in volcanic reservoirs with well logging data, Ge et al. proposed a method for identifying the degree of fracture development on the basis of the combination of PCA and multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis, which successfully predicted the degree of fracture development of volcanic reservoirs in the Tarim Basin25. In summary, the PCA method is now highly recognized for the types of reservoirs that have been discovered and produced at scale.

In this study, the authors aim to utilize the PCA method, which has proven successful in other reservoirs, to derive a parameter or model that serves as a highly indicative indicator of effective gas reservoirs for the Longdong area in the Ordos Basin. This paper first provides a comprehensive overview of the essential characteristics of Al-bearing rock layers through an analysis of geochemistry, rock minerals, and logging features. This study identifies diaspore as the characteristic mineral of an effective gas-bearing reservoir and emphasizes the importance of the aluminium oxide content as a key parameter. The conventional logging curves are subsequently dimensionally reduced via the PCA method to derive a new uncorrelated variable (principal component). On the basis of the relationships among lithology, the Al2O3 content, and the principal components obtained via PCA, a lithological division chart and an effective reservoir identification model based on PCA are established. The lithological division method uses 2 principal components derived from 8 conventional logging curves to preliminarily identify potential reservoirs. A reservoir identification model with a reasonable goodness of fit eliminates multicollinearity in direct linear regression. Moreover, the weight coefficient assigned to each variable reflects genuine geological principles, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent research endeavours. Verified by production test data, the method based on PCA processing constitutes an effective and rapid approach for the identification of bauxite gas reservoirs without other test data during exploration and development.

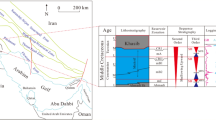

Geological background

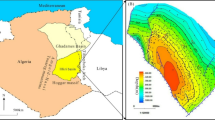

The study area is situated in the southwestern Ordos Basin and spans two tectonic units: the Tianhuan depression and the Yishan slope (Fig. 1a). At the end of the Ordovician, influenced by the Caledonian Movement, the North China epicontinental basin was uplifted to become land, causing a sedimentary hiatus of approximately 130 million years from the Middle Ordovician to the Early Carboniferous, and the absence of Silurian to Devonian strata. During this period, carbonate rocks of the Ordovician Majiagou Formation were exposed to the surface and gave rise to karst landforms. At the end of the Carboniferous Benxi Age, seawater from the Qinqi sea and the North China sea invaded the central palaeouplift in the central and western parts of the Ordos basin, and the Ordos area subsided and received new deposits. Nevertheless, owing to its location in the karst highlands, the Longdong area has not received the depositions of the Benxi Formation. In the early Permian Taiyuan stage, the transgression expanded, and the Longdong area deposited Taiyuan Formation strata.

From the Carboniferous to Permian, the North China Block was located in the low and middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. It had mainly tropical and subtropical summer wet ecosystems, as well as equatorial tropical ever-wet ecosystems. The Lower Palaeozoic karst system developed due to high temperatures, rainfall, and the rise and fall of sea level. These factors provided favourable drainage structures for the weathering and leaching of the original upper Palaeozoic deposits. Moreover, the rise and fall of sea level caused ferrallitization and gleization of the original sediments from the Carboniferous to the Permian, which led to the formation of Al-bearing rock series on the basin margin.

The Palaeozoic strata in the study area include the lower Palaeozoic Cambrian system (the Maozhuang Formation, Xuzhuang Formation, Zhangxia Formation, and the Sanshanzi Formation), the Ordovician system (the Majiagou Formation only) and the upper Palaeozoic Permian system (the Taiyuan Formation, Shansi Formation, Shihezi Formation, and Shiqianfeng Formation). The bauxite reservoir discussed in this paper is in the Taiyuan Formation of the upper Palaeozoic Permian system. The Taiyuan Formation is within a transitional sedimentary environment, and features coal seams, carbonaceous mudstone, mudstone containing limestone, and the Al-bearing rock series (Fig. 1b). The bauxite reservoir discussed in this paper is located in the middle stratum of this aluminous rock series (Fig. 1b). The Al-bearing rocks show significant vertical variation in element enrichment due to weathering and leaching. To identify the gas reservoirs in the Al-bearing rock series efficiently and accurately on the basis of the predicted principal element content, a regression relationship was established between conventional logging and principal element content via tests, core observations, cuttings, and conventional logging data.

Methods

Major element test

Owing to the comprehensive effects of palaeostructure, palaeolatitude and palaeoclimate, a bauxite-rich stratum with a bean-shaped oolitic structure and diaspore formed26,27,28. Under the transformation of palaeokarst14,29, the soluble components in the bean-shaped oolitic structure dissolved to form intragrain soluble pores, matrix soluble pores and residual lattice pores, causing bauxite to become a favourable place for oil and gas storage. Therefore, the distribution of bauxite reservoirs is largely controlled by the content of diaspore minerals. The layer with a high diaspore content, well-developed bean-shaped ooids, and detritus is usually the main effective reservoir with good porosity. In contrast, clay rock with a low content of aluminium and without ooids and detritus cannot be used as an effective reservoir because of its weak karst corrosion and poor physical properties.

The primary chemical components play crucial roles in the origin, formation, and evolutionary processes of rocks. Specifically, they offer valuable insights into sedimentation and diagenesis. This test utilized the continuous variation in major elements along the vertical well section to preliminarily determine the mineral composition of the Al-bearing rock and aid in understanding pore formation as well as the relationship between porosity and aluminium mineral content. The concentrations of major element oxides were determined by 36 inductively coupled plasma (ICP) measurements. The samples were obtained from Well LD58 in the study area. After grinding and sieving procedures, these samples underwent high-temperature chemical treatment to enable dissolution, yielding a 40-millilitre solution for further analysis.

X-ray diffraction analysis

While bauxite rocks present higher aluminium contents, clay rocks also exhibit significant concentrations of aluminium. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis not only reveals the source minerals responsible for aluminium but also provides insights into the enrichment mechanisms based on longitudinal variations in mineral composition. After the XRD patterns were obtained, the sample X-ray diffraction data were compared with the standard mineral data for qualitative analysis. The Rietveld full-spectrum fitting method was used for semiquantitative analysis, with specific methods and steps described in the literature30. Twenty-three core samples were acquired from the well section for X-ray diffraction analysis. Preprocessing and testing of all the rock samples were performed at the Continental Dynamics Key Laboratory at Northwestern University. A D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer from Bruker AXS in Germany was utilized to perform this test, with instrument parameters including a Lynx XE array detector, a Cu target, a ceramic X-ray tube, a voltage of 40 kV, and a current of 40 mA. Continuous scanning mode was adopted, with a range of angles of − 110 to 168° (2θ), an angle accuracy of 0.0001°, a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning speed of 0.2 s per step.

Principal component analysis

PCA is in a category of unsupervised learning in machine learning. The core concept is to calculate new variables by linear transformation of multiple variables. The new variables are called principal components (PCs), and they are uncorrelated with each other and ranked in order of importance from the largest to the smallest18,20,23,31. Through PCA, dimension reduction, noise removal and simplification of data can be achieved through dimensionality reduction. Multiple logging indices are transformed into a few principal components, each of which reflects most of the original logging information, to show the essential relationship between the logging and geological information to the greatest extent by using fewer variables. The above concept of PCA can be visualized through an illustration via only two parameters, as shown in Fig. 2. Three genes can be classified into two principal components, PC1 and PC2. For a more extensive set of log parameters, the mathematics remains unchanged, but visualizing the geometry is challenging32.

The PCA method involves three key steps33,34 (Fig. 2). First, the data sets are standardized by standard deviation normalization method to obtain a standardized matrix. The covariances between standardized variables are subsequently calculated. The main diagonal represents the covariance of the identical variable, whereas the upper and lower triangles of the matrix denote the covariance between distinct values. Finally, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors are derived from the covariance matrix to reveal the underlying patterns in the data. Once eigenvectors are obtained from the covariance matrix, they are arranged in descending order of significance. Typically, the first two components contain maximum variances of the data of interest needed for evaluation35,36. In this study, eight conventional well logs, including gamma ray (GR), compensated neutron log (CNL), density (DEN), uranium (U), thorium (TH), acoustic time (AC), resistivity (R), and potassium (K) logs, were selected as source data. The Z-score standard deviation was employed to standardize these logs and calculate their covariance matrix. Following the core principles of PC extraction, multiple uncorrelated principal components with decreasing importance could be extracted.

Results

Major element contents

The results of major element tests of 36 rock samples are shown in Fig. 3. The major elements clearly stratify in the vertical direction. The well sections from 4038.6 to 4141.2 m and 4042.8 to 4045.2 m have low contents of Al2O3, TiO2, and K2O and high contents of SiO2. The well sections from 4041.2 to 4042.8 m and 4045.8 to 4051.1 m have high contents of Al2O3 and TiO2 and low contents of K2O and SiO2. The well section from 4051.1 to 4060 m has low contents of Al2O3 and TiO2 and high contents of K2O and SiO2.

The vertical chemical composition of the Al-bearing layer reflects the degree of weathering and leaching37,38,39,40. During chemical weathering, alkali metals and alkaline earth metals in high-aluminium-containing sections are typically dealkalized and leached to the lower layer because of their strong activity, resulting in a high content of K in the lower layer. Al2O3 and TiO2 showed an evident positive correlation, whereas Al2O3 and SiO2 showed an evident negative correlation (Fig. 4). During bauxite mineralization, the inactive elements, Al and Ti, exhibit the geochemical behaviour of comigration and coenrichment. In the chemical weathering process, Al and Si are initially enriched by dealkalization, and then continuous leaching and desilication cause Si to migrate downwards, resulting in the accumulation of Si at the bottom of the formation.

The Al-bearing rock series can be divided into seven types (Fig. 5) on the basis of the contents of silicon oxide (SiO2), aluminium + titanium oxide (Al2O3 + TiO2), and ferric oxide (Fe2O3): Fe-poor bauxite, bauxite, ferruginous bauxite, bauxitic ferruginous ore, clayey bauxite, clayey iron rock, and bauxitic clay41,42. Table 1 shows the mineral composition characteristics of the different lithologies. Only three of the seven classes shown in Fig. 5 are present in the study area: Fe-poor bauxite (for simplification, hereinafter referred to as bauxite), clayey bauxite, and bauxitic clay.

XRD mineral content

The results of the whole-rock X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 6) indicate that diaspore and clay minerals are the main composition in Al-bearing rock, with diaspore accounting for 36.6–94.1% of the total composition, which is predominantly found in the middle strata at depths ranging from 4043 to 4055 m, where it exceeds 70%. The high Al2O3 content in Al-bearing rocks is caused mainly by the diaspore. Clay minerals were mostly detected in the upper and lower parts (shallower than 4043 m and deeper than 4055 m, respectively) of the aluminous series, ranging from 2.1 to 35.7% (Fig. 6). In addition, minor occurrences of potassium feldspar, pyrite, and anatase were observed. The results indicate that kaolinite, montmorillonite, chlorite, and illite are the main clay minerals present in this Al-bearing rock series. Kaolinite contents range from 1.3 to 24.3%, chlorite contents range from 0.7 to 19.3%, and illite contents range from 0.2 to 6.9%. The presence of significant amounts of illite below 4055 m again indicates that the soluble K was leached to the lower strata to form illite, which was enriched at the bottom.

Logging response

On the basis of the above test data, a log value comparison of different intervals with varying levels of aluminum contents within the Al-bearing rock series of the Taiyuan Formation indicates that favourable gas formations with higher aluminium contents generally present high GR, high CNL, high DEN, high U, high TH, low AC, low R, and low K values (Table 2; Fig. 7).

Figure 7 presents a comprehensive illustration of the correlation between the Al2O3 content and each logging value, providing valuable insights into the relationship between the diaspore content and logging value. The data clearly indicate that an increase in diaspore content corresponds to a significant increase in U, Th, CNL, and GR values. Particularly noteworthy is the strong correlation observed between the GR values and the Al content, highlighting the influence of diaspore on GR. Furthermore, there is a clear negative correlation between the K logging value and the Al content. Additionally, the resistivity logging value consistently shows a negative correlation with increasing Al content; as the Al content increases, the resistivity decreases accordingly. Moreover, when AC and DEN are analyzed in relation to the Al content, it becomes evident that there is no obvious correlation between them.

The radioactivity of bauxite is very low, but the Al-rich well section shows a high GR on the log curve. The accumulation of radioactive U and Th in bauxite due to its strong adsorption is not the reason why the gamma value is high in well logs, because aluminous rock in the lower section of the Al-bearing rock series is stronger in terms of adsorption but lower in U and Th contents. Notably, the anatase content in the bauxite layer is always positively correlated with diaspore; anatase often coexists with highly radioactive U and Th and is the key to bauxite formation, resulting in high gamma values in the log curve. However, radioactive K is not enriched in the Al-rich layer, which is directly related to the downwards leaching migration of K+ during the late evolution of the aluminous rock.

There are two main reasons for the high neutron response values in the highly aluminized strata. On the one hand, the oolites and detritus developed in bauxite often undergo strong transformation in the late diagenetic stage and form dissolution pores. Dissolution is more common during diagenesis when bean-shaped oolites and detritus are developed in reservoirs, thus leading to a higher porosity and higher content of hydrogen-containing fluid and CNL. On the other hand, bauxite inevitably contains a large amount of diaspore, and the H in its crystal structure also results in a high CNL value.

In summary, GR, CNL, U and Th are the main log curves that respond significantly to bauxite with high aluminium contents. In addition, owing to the presence of various metal minerals, such as diaspore, anatase, and pyrite, the log curves of the bauxite layer are characterized by high density. Moreover, dissolution pores in the highly aluminized strata result in low resistivity. On the one hand, the formation water content is relatively high in the strata featuring developed pores, which constitutes the primary cause of the low resistivity. On the other hand, the intervals with developed pores are frequently those with high aluminium contents. Owing to the presence of metal elements such as Al, to a certain extent, the conductivity of the rock matrix is also increased, thereby resulting in a low resistivity. A log identification standard for Al-bearing formations is established on the basis of the Al2O3 content and conventional logging data.

In the well bauxite deposits developed in the study area, clayey rocks are generally distributed at the top and bottom of the Al-bearing formations. Compared with bauxite, clay rocks have evident differences in GR, CNL, U, Th, R and other log curves. The K content of clay rock developed at the bottom is significantly different from that of clay rock developed at the top, which is directly related to the downwards leaching migration of K+ during the late evolution of the Al-bearing rock. Clayey bauxite and bauxitic clay rock are transitional lithologies between clay and bauxite. Clayey bauxite has higher natural GR, CNL, R, U, and TH values and lower AC and K values than bauxitic clay rock. According to the degree of dissolution pore development, the bauxite layer should be the first choice for effective gas reservoirs, followed by clayey bauxite and bauxitic clay rock.

On the basis of the above analysis, bauxite deposits with higher concentrations of alumina can serve as more effective reservoirs, whereas clayey bauxite and bauxitic clay with high clay contents tend to have poorer reservoir properties. To further support this view, Fig. 8 presents the core photograph, thin section, and porosity data from Well LD58 in the study area, illustrating the physical characteristics of all types of rocks.

Reservoir porosity

The porosity data from conventional tests were sourced from the Changqing Oilfield. Figure 8 clearly shows patterns of vertical variation in aluminium content and porosity throughout the different rock layers of Well LD58. For the clayey bauxite and bauxitic clay layers in the upper well Sect. (4042–4045.2 m), the relatively dense core has an Al2O3 content of less than 40.0% and an average porosity of 7.74%. Although clumps and clastic layers are distributed throughout, there is no significant dissolution, and pyrite and siderite nodules can sometimes be observed. In the bauxite formation (4045.2–4053.5 m), the core is characterized by porous structural features. The slide deformation observed in the thin section of the rock suggests that local slip and collapse occurred during the early or middle stage of sediment-consolidated diagenesis, as the sediments were not yet fully consolidated. The oolites and beans were extensively dissolved, and residual oolitic and clastic materials developed, creating pores of various sizes. This well section contains a significant reservoir in the Al-bearing rock series, and the Al2O3 content is high, with an average of 60%, up to 75%. The average porosity of the bauxite layer is 15.66%, with a maximum value of 28.7%. The development of secondary dissolution pores that contribute significantly to porosity indicates that bauxite underwent chemical dissolution during diagenesis. Eventually, it led to the leaching of soluble elements and the enrichment of Al. In the lower well Sect. (4053.5–4057.8 m), the clayey bauxite and bauxitic clay rocks are dominated by clay minerals, with an average Al2O3 content of 40.0% and a porosity of 7.75%. The particles exhibit flattening and elongation along the surface, and sedimentary lamination is well developed. The thin section shows that the breccia is microcrystalline bauxite with subangular shapes, indicating that the previously formed bauxite rock underwent some transportation and abrasion again, but the corners were not completely rounded, and some original shapes were retained. Secondary dissolution pores are developed in this layer, but aluminium ions or other Al-containing substances in the fluid reprecipitated under appropriate conditions, forming diaspore and completely filling the original dissolution pore space, resulting in poorly developed pores in this section.

Figure 8 shows that bauxite deposits with higher Al2O3 concentrations exhibit improved porosity due to mineral dissolution. In contrast, rocks with high clay contents tend to have lower porosities, making it difficult for hydrocarbons to migrate and accumulate. The above segmented structure of the bauxite series is closely related to sea level rise and fall. The entire sedimentary environment of the late Palaeozoic North China landmass was an epicontinental sea. When the sea level fell, the original sediment was exposed to the surface and subjected to weathering, leaching, activation and migration of soluble elements, and enrichment of relatively stable elements such as aluminium, resulting in an increase in the Al2O3 content and the formation of dissolution pores. When the sea level rose, the sediment was under water and was exposed to a reducing environment. Silicification occurred, aluminium was replaced, and the aluminium content decreased to form a clay layer with high silicon and low aluminium contents. Owing to the limited circulation of water, dissolution pores did not develop. Therefore, alumina-rich bauxite clearly serves as a more effective reservoir than clay-rich rocks. To summarize, the data presented in Fig. 7 provide ample evidence that supports our main thesis, which is that a high alumina concentration is a critical factor in determining the effectiveness of oil reservoirs. Precisely, when the Al2O3 content within the reservoir rock exceeds 60%, distinct dissolution pores are generated within the rock, and this type of reservoir consistently exhibits a relatively high hydrocarbon content in gas logging. Consequently, these reservoirs can be initially recognized as effective ones. With this insight, we can better predict and optimize the exploration of bauxite gas resources, thereby improving the efficiency of our energy sector.

Principal component

After linear dimension reduction of the standardized data, a total of 8 principal components (PCs) were generated (Table 3); the eigenvalues of Components 1 and 2 (denoted Y1 and Y2, respectively) were both greater than 1, and were 4.417 and 2.041, respectively. The contribution ratios of Y1 and Y2 were 55.217% and 25.509%, respectively. Specifically, Y1 and Y2 account for 80.726% of the total variables, indicating that these two components are sufficient to represent formation logging information with less loss of data information and can better show the essential trend44. Therefore, the first two components are used as the main components.

Combined with the weight coefficient (feature vector), the two principal components Y1 and Y2 can be expressed as follows:

By comparing the weight coefficients of the logging standard values, it can be inferred that the first component, Y1, predominantly reflects lithologic information on the basis of its higher weights for GR, U and TH. Similarly, the second component, Y2, primarily represents pore information as indicated by its higher weights for AC and DEN.

Discussion

Lithological division and identification

According to the lithological identification results from the cross plot from Well LD58 (Fig. 9), the distribution of log data of different lithologies has a large overlap zone, and there is no clear boundary between different lithologies. On the basis of Eqs. (1) and (2), the major element test data from 31 Al-bearing rock samples were used to conduct PCA. During PCA-based lithological identification, only Al-bearing rock samples were utilized, as siliceous rocks and carbonaceous mudstones could be identified without requiring special treatment. The PCA results, the principal components of Y1 and Y2 and the comprehensive score Y of the 8 conventional log curves produced the correlations shown in Fig. 10.

The results show that the principal component Y1 and comprehensive score Y increase linearly with increasing aluminium content, whereas Y2 tends to decrease with increasing aluminium content. The lithology shows evident linear zonation in the Y-Y1 chart. Bauxite is distributed mainly in the Y1 ≥ 2 and Y ≥ 1 regions, clay bauxite is distributed in the 2 > Y1≥ − 0.5 and 1 > Y ≥ − 0.5 regions, bauxitic clay rock is distributed in the − 0.5 > Y1≥ − 2 and − 0.5 > Y≥ − 1 regions, and clay rock is located in the Y1 < − 2 and Y< − 1 regions. The lithology presents evident two-dimensional zoning in the Y-Y2 and Y1-Y2 charts. Owing to some overlap of Y2 for different lithologies, the lithology can be divided according to Y2 as an alternative scheme. An effective bauxite gas reservoir has the highest Y and Y1 and the lowest Y2, whereas clay rock has the lowest Y and Y1 and the highest Y2.

Al2O3 content prediction and reservoir location

The linear regression model of the Al2O3 content (TAL) and principal components Y1 and Y2 is as follows:

According to the standardized processing and the Eqs. (1) and (2), the expression of each logging value is further rewritten as follows:

Equation (4) shows that the Al2O3 content of the bauxite gas reservoir is negatively correlated with AC, R and K and positively correlated with CNL, DEN, GR, TH and U, which is consistent with the well logging geological response characteristics of bauxite reservoirs mentioned previously.

Figure 11 shows the results with and without PCA. By comparison, the Al2O3 content calculated via the regression model based on PCA is in good agreement with the test results. The fitting coefficient is 0.93 (Fig. 11a), which indicates that the model has a good effect on predicting the Al2O3 content and can be used to accurately indicate favourable reservoir strata with high aluminium contents. Compared with PCA, direct multiple linear regression of log data and the Al2O3 content is a more concise mathematical statistical method, and its fitting formula is as follows:

According to the principle of least squares, the corresponding fitting coefficient βi and its intercept β0 from the different log curves can be obtained via the Cholisky decomposition method:

The fitting degree (R2) between the predicted value and the measured value was 0.949 (Fig. 11b), surpassing the accuracy of the regression algorithm based on PCA. The log values, such as GR, U, Th, etc., exhibit inherent correlations that necessitate the assessment of multicollinearity in the linear regression model. Each independent variable (Eq. (5)) in the regression model was regressed against other independent variables, and subsequently, tolerance (T) and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were computed (Table 4). The results indicate that the established regression model without PCA demonstrates multicollinearity, as evidenced by a tolerance value below 0.1 and a VIF exceeding 10. As geological researchers, we not only strive for enhanced model accuracy but also emphasize the geological interpretation of independent variables. However, the weight coefficients of Eq. (6) were not consistent with the geological significance of each log curve. As seen from our major element test, the Al2O3 content is highly positively correlated with U, and the correlation coefficient reaches 0.66, whereas the coefficient of U is negative (− 0.165) according to the multiple regression results. Moreover, an effective reservoir is closely related to the leaching of soluble K+, which indicates that the Al content should be negatively correlated with the K content, but the coefficient of K in the regression in Eq. (6) is positive (+ 0.170). The above problems are caused by the strong correlation among the logs, which leads to serious multicollinearity among the logging variables. Therefore, multiple regression as a statistical method to address the relationships among variables is feasible, but it does not provide a reasonable interpretation of logging geology.

In addition to dimension reduction and linear regression, we employed random forest (RF), decision tree classifier (DTC), and support vector machine (SVM) algorithms to predict the Al2O3 content (Fig. 12). The findings compared with those in Fig. 11 illustrate that various approaches result in distinct errors and levels of fit. The SVM algorithm with higher complexity has a relatively low R2 value; the remaining three algorithms demonstrate a relatively high level of goodness-of-fit. Among them, the PCA regression method may yield slightly lower R2 values than the RF, linear regression, and DTC methods because of its non-100% contribution degree. Notably, this study aims to identify an algorithm capable of rapidly and effectively identifying potential reservoirs while providing information for subsequent logging data mining and geological research. Therefore, it is crucial not only to achieve high data accuracy but also to ensure that the model reflects geological phenomena and laws. Although the DTC, RF, and linear regression algorithms achieved relatively high data accuracy, as expected by mathematicians, geologists prefer visually interpretable models that are suitable for geological research with reasonable accuracy. The PCA-based formula for the Al2O3 content yields relatively accurate predicted values; its advantage over the RF, DTC, and SVM algorithms lies in the fact that the relationship between the source data and target data is not a black box–i.e., the correlation between the Al2O3 content and well logging data can be visualized. Consequently, for field applications and geological research purposes, the PCA-based regression equation in reservoirs is more applicable.

Application effect

The above research results are applied to lithological identification of the bauxite-bearing formation of the Taiyuan layer in Well LD58. Coal seams and carbonaceous mudstones can be identified directly according to acoustic wave and density curves. The lithology of the aluminous rocks is determined based on the boundary values of Y, Y1, and Y2 corresponding to different lithologies in Fig. 10. For example, in well sections from 4043.2 to 4044.7 m and 4046.3 to 4053.7 m in Fig. 13, where Y1 ≥ 2 and Y ≥ 1, the lithology is identified as bauxite according to Fig. 10; similarly, in well sections from 4040.1 to 4043.2 m and 4053.7 to 4055.2 m in Fig. 13, where 2 > Y1≥ − 0.5 and 1 > Y ≥ − 0.5, the lithology is classified as clayey bauxite. The principal components of Y1 and Y2 and the composite score Y of conventional log curves have evident stratification characteristics (Fig. 13).

In Fig. 13, the sixth, seventh and eighth tracks represent the principal components of Y1 and Y2 and the comprehensive score Y, respectively. The lithological identification results, which are based on the Al2O3 content and PCs of the interpretation chart (Fig. 10), are shown in the last track. The Al-bearing layer of the Taiyuan formation in LD58 can be divided into 10 intervals. Two bauxite deposits from 4043.2 m to 4044.7 m and 4046.3 m to 4053.7 m are identified. Compared with ICP, both regression analyses with and without PCA demonstrated variations in the Al content in the strata; however, the application of PCA to the bauxite layer yielded more precise regression results, which indicates that this method has a good ability to identify the lithology of the Al-bearing layer in the Longdong area.

According to the Al2O3 content prediction equation, another well (LD47) was selected for lithological identification and reservoir prediction (Fig. 14). The sixth track is the predicted content of Al2O3 via PCA. On the basis of the corresponding relationship between the Al2O3 content and the degree of pore development (Fig. 8), the high-aluminium section with an Al2O3 content exceeding 60% is preliminarily determined as an effective reservoir (the red part in the sixth track). The seventh track is the result of gas logging, and its high value in the red well section of the sixth track represents the potential gas zone with a relatively high hydrocarbon content, which further validates the effectiveness of the reservoir prediction on the basis of the Al2O3 content. The prediction results of the Al2O3 content via PCA reveal that there are two high aluminium contents at the bottom of the Taiyuan Formation (P1t) in Well LD47: one from 4101.4 ~ 4105.8 m and the other from 4112.4 ~ 4119.8 m. The gas logging data obtained from these two intervals demonstrate excellent characteristics, with a peak value of 86.8149% and a base value of 2.4753%, which aligns remarkably well with the predicted Al-rich segments.

The production test curves of the two potential intervals are presented in Fig. 15, which confirms the reliability of the regression model established in this study for effectively identifying reservoirs in Al-bearing formations. The perforated interval was set at 4103 ~ 4106 and 4113 ~ 4115 m. The annulus volume fracturing technique was employed to achieve a high production industrial gas flow rate of 67.3832 × 104 m3/day (AOF). A trial production period of 45 days was conducted, with initial oil and casing pressures of 26.72 and 26.75 MPa, respectively. In the initial stage, production was carried out at 30,000 m3/day, with rapid decreases in oil pressure and casing pressure. After 35 days, the production allocation was adjusted to 20,000 m3/day. Throughout the trial production period, a decrease in liquid production was accompanied by an increase in chlorine content, indicating a favourable flowback effect. Posttest production analysis revealed daily decreases of 0.19 MPa and 0.20 MPa for the casing pressure and oil pressure, respectively. The cumulative gas production reached 1,245,166 m3, whereas the cumulative water production reached only 73.6 m3.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Major elements have regular stratification in the vertical direction. During bauxite mineralization, the comigration and coenrichment of the inactive elements, Al and Ti, led to an evident positive correlation between Al2O3 and TiO2. Leaching and desilication caused an evident negative correlation between Al2O3 and SiO2, and Si was enriched at the bottom of the Al-bearing formation. The soluble K was leached to the lower strata to form illite, which was enriched at the bottom. According to the Al2O3 content, aluminous rock can be divided into clay rock, bauxitic clay rock, clayey bauxite and bauxite.

-

(2)

A bauxite deposit with a high aluminium content is an effective gas reservoir with dissolved pores, showing the characteristics of “five high and three low” (high GR, CNL, DEN, U and TH and low AC, R and K). The lithological boundary of Al-bearing rock is not very clear in conventional log cross plots. The four lithologies can be clearly divided into Y-Y1 charts, Y-Y2 charts and Y1-Y2 charts on the basis of linear dimension reduction. Moreover, the effective bauxite reservoir has the highest Y and Y1 and the lowest Y2. However, more tests and well log data are needed to further define the boundaries of Y, Y1, and Y2 for Al-bearing lithologies in the database that the division chart referenced.

-

(3)

The prediction model of the Al2O3 content established via regression based on PCA not only reasonably fits the test results but also reflects the variation characteristics of the Al content in Al-bearing rocks with respect to logging values, avoiding the phenomenon of “value true but meaning false” caused by the multicollinearity of multiple regression. The lithological identification chart and the major element content prediction equation established in this paper have good applicability to the identification of effective bauxite gas reservoirs.

Data availability

The data sets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fu, J. H. et al. Breakthrough in the exploration of bauxite gas reservoir in Longdong area of the Ordos basin and its petroleum geological implications. Nat. Gas Ind. 41 (11), 1–11 (2021).

Meng, W. G. et al. Research on gas accumulation characteristics of aluminiferous rock series of Taiyuan Formation in Well Ninggu 3 and its geological significance, Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 26 (3), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7703.2021.03.007 (2021).

Yu, H. Z. et al. The formation of the dense sandstone cap in the Well 2, Tarim Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 31 (5), 133–135. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-0747.2004.05.037 (2004).

Cheng, F. Q., Jin, Q., Liu, W. H. & Chen, M. J. Formation of source-mixed gas reservoir in Ordovician weathering crust in the central gas-field of Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 28 (1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0253-2697.2007.01.007 (2007).

Yu, H. Y. et al. Gas and water distribution of Ordovician Majiagou formation in northwest of Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 43 (3), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1876-3804(16)30050-7 (2016).

Si, Z. W. et al. Research on well logging evaluation method of igneous reservoir in Nanpu 5 structure. Energy Sources Part. A. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1798565 (2020).

Lu, S. Y., Deng, R., Song, L. H. & Wu, S. L. Identification and logging evaluation of poor reservoirs in X Oilfield. Open. Geosci. 13 (1), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1515/geo-2020-0280 (2021).

Liu, W. K. et al. XGBoost formation thickness identification based on logging data. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 918384. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.918384 (2022).

Anees, A. et al. Identification of favorable zones of gas accumulation via fault distribution and sedimentary facies: insights from Hangjinqi area, northern Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 822670. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.822670 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Genetic mechanism of the large Carboniferous Aiyutou karstic bauxite in North China Craton. Acta Petrol. Sin. 39 (2), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.18654/1000-0569/2023.02.20 (2023).

Liu, X. F. et al. Mineralogical characteristic of bauxite samples from Napo Bauxite deposit, Guangxi province, China. Smart Sci. Explor. Min. 1 & 2, 120–122 (2010).

Laskou, M. D. Geochemical and mineralogical characteristics of the bauxite deposits of western Greece. Mineral. Explor. Sustainable Dev. 1 & 2, 93–96 (2003).

Singh, B. P. Petrographical, mineralogical, and geochemical characteristics of the Palaeocene lateritic bauxite deposits of Kachchh Basin, Western India. Geol. J. 54 (4), 2588–2607. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.3313 (2019).

Mondillo, N. et al. Petrographic and geochemical features of the B3 bauxite horizon (Cenomanian-Turonian) in the Parnassos-Ghiona area: a contribution towards the genesis of the Greek karst bauxites. Ore Geol. Rev. 143, 104759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2022.104759 (2022).

Zhu, L. Q. et al. Well logging evaluation of fine-grained hydrate-bearing sediment reservoirs: considering the effect of clay content. Pet. Sci. 20 (2), 879–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2022.09.018 (2023).

Cheng, C. et al. Advances in logging evaluation of shale distribution in clastic rocks. Prog Geophys. 36 (3), 1052–1061 (2021).

Pasadakis, N. Determination of the continuity in oil reservoirs using principal component. Pet. Sci. Technol. 20 (9–10), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1081/LFT-120003699 (2002).

Jolliffe, I. T. & Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 374, 20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202 (2016).

Chen, Y. J. & Hao, Y. J. Integrating principle component analysis and weighted support vector machine for stock trading signals prediction. Neurocomputing. 321, 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.08.077 (2018).

Wolf, M. & Pelissier-Combescure, J. Faciolog-automatic electrofacies determination. SPWLA 23rd Annual Logging Symposium, Corpus Christi, Texas, SPWLA-1982-FF (1982).

Gao, Y. & Li, Z. X. Interpretation of porosity for tight glutenite based on principal component analysis. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 34 (4), 716–724. https://doi.org/10.14027/j.cnki.cjxb.2016.04.012 (2016).

Jahan, I. C., Castagna, J., Murphy, M. & Kayali, M. A. Fault detection using principal component analysis of seismic attributes in the Bakken formation, Williston basin, north Dakota, USA. Interpretation-A J. Subsurface Charact. 5 (3), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2016-0209.1 (2017).

Karimi, A. M., Sadeghnejad, S. & Rezghi, M. Well-to-well correlation and identifying lithological boundaries by principal component analysis of well-logs. Comput. Geosci. 157, 104942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2021.104942 (2021).

Li, W., Chen, T. J., Song, X., Gong, T. Q. & Liu, M. Y. Reconstruction of critical coalbed methane logs with principal component regression model: a case study. Energy Explor. Exploit. 38 (4), 1178–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144598720909470 (2020).

Ge, X. M., Fan, Y. R., Zhu, X. J., Deng, S. G. & Wang, Y. analysis (KPCA) A Method to differentiate degree of volcanic reservoir fracture development using conventional well logging data-an application of kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) and multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MFDFA). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 7 (12), 4972–4978. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2319392 (2015).

Nesbitt, H. W. & Young, G. M. Early proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nat 299(21), 715–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/299715a0 (1982).

Yang, S. J. et al. Mineralogical and geochemical features of karst bauxites from Poci (western Henan, China), implications for parental affinity and bauxitization. Ore Geol. Rev. 105, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2018.12.028 (2019).

Zhao, L. H. et al. Genetic mechanism of super-large karst bauxite in the northern North China Craton: constrained by diaspore in-situ compositional analysis and pyrite sulfur isotopic compositions. Chem. Geol. 622, 121388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121388 (2023).

Jiu, B., Huang, W. H., Mu, N. N. & Li, Y. Types and controlling factors of ordovician paleokarst carbonate reservoirs in the southeastern Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 198, 108162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.108162 (2021).

Andrade, F. R. D., Polo, L. A., Janasi, V. D. & Carvalho, F. M. D. Volcanic glass in cretaceous dacites and rhyolites of the Parana Magmatic Province, southern Brazil: characterization and quantification by XRD-Rietveld. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. (SI). 355, 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.08.008 (2017).

Beattie, J. R. & Esmonde-White, F. W. L. Exploration of principal component analysis: deriving principal component analysis visually using spectra. Appl. Spectrosc. 75 (4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702820987847 (2021).

Lim, J. S. Multivariate statistical techniques including PCA and rule-based systems for well log correlation. Dev. Petrol. Sci. 51, 673–688 (2003).

Kumar, T., Kumar, S. N. & Rao, G. S. Automatic lithology modelling of coal beds using the joint interpretation of principal component analysis (PCA) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT). J. Earth Syst. Sci. 132(10), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-022-02018-5 (2023).

Saucier, A. & Muller, H. Using principal component analysis to enhance the generalized multifractal analysis approach to textural segmentation: theory and application to microresistivity well logs. Phys. (Amsterdam Neth). 309 (3–4), 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(02)00611-8 (2002).

Chen, C., Gao, G., Ramirez, B. A., Vink, J. C. & Girardi, A. M. Assisted history matching of channelized models by use of pluri-principal-component analysis. SPE J. 21 (5), 1793–1812. https://doi.org/10.2118/173192-PA (2016).

Khanal, A., Khoshghadam, M., John, W. L. & Nikolaou, M. New forecasting method for liquid rich shale gas condensate reservoirs with data driven approach using principal component analysis. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 38, 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2017.01.014 (2017).

Mongelli, G. Growth of hematite and boehmite in concretions from ancient karst bauxite: clue for past climate. Catena. 50 (1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(02)00067-X (2002).

Mongelli, G., Boni, M. & Buccione, R. Geochemistry of the apulian karst bauxites (Southern Italy): chemical fractionation and parental affinities. Ore Geol. Rev. 63, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2014.04.012 (2014).

Sinisi, R. Mineralogical and geochemical features of cretaceous bauxite from San Giovanni Rotondo (Apulia, Southern Italy): a provenance tool. Miner. 8 (12), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8120567 (2018).

Abedini, A., Mongelli, G. & Khosravi, M. Geochemistry of the early Jurassic Soleiman Kandi Karst Bauxite deposit, Irano-Himalayan belt, NW Iran: constraints on bauxite genesis and the distribution of critical raw materials. J. Geochem. Explor. 241, 107056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2022.107056 (2022).

Bárdossy, G. Karst bauxites: bauxite deposits on carbonate rock. Dev. Econ. Geol. 14, 1–441 (1982).

Bárdossy, G. & Aleva, G. J. J. Lateritic bauxites. Dev. Econ. Geol. 27, 1–624 (1990).

Krasnova, A. V. & Rostovtseva, Y. V. Bauxite reservoirs at the contact zone between Paleozoic and mesozoic deposits of the west siberian plate. Mosc. Univ. Geol. Bull. 76 (1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.3103/S014587522101004X (2021).

Hu, H., Zeng, H. Y., Liang, H. B. & Tang, Y. Q. Application of PCA-LVQ neural network Model in lithology identification by logging data in Panzhuang Area. Pak J. Stat. 30(6), 1219–1230 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors express special gratitude to the Petrochina Changqing Oilfield Company for providing basic data and support for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and J.G. wrote the main manuscript text. Z.M. provided the rock samples and some data information. All authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Guo, J., Ma, Z. et al. Rapid identification of an effective bauxite gas reservoir by principal component analysis. Sci Rep 14, 23466 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74611-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74611-1