Abstract

Lake Burlan, a lentic ecosystem artificially created by untreated runoff from adjacent rice fields, is located in the Amazon region within the dry forests of northern Peru. This body of water plays a fundamental role in agriculture and recreational activities in the area, which are fundamental to the local economy. This research aimed to evaluate the water quality of Lake Burlan using the Water Quality Index of Peru (WQI-PE). In addition, both spatial and depth variations of limnological parameters and trace elements were determined. The WQI-PE was calculated at seven sampling stations at two depths (surface level and one meter), using 18 limnological parameters and nine trace elements. The WQI-PE assessment indicated that the lake water quality ranged from poor to fair for both depths. Statistical analysis showed that nine limnological parameters and five trace elements showed spatial differences across seven sampling stations, while three limnological parameters and two trace elements showed depth-dependent variations. Concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead were in exceedance of the national and international standards on environmental water quality. Therefore, the water quality of Lake Burlan is affected mainly by the impact of the surrounding rice fields and recreational activities. This research establishes a starting point for future monitoring to assist in the implementation of prevention and mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lakes are aqueous formations located within a cavity in the continental land surface1. They are among the most important water resources, mostly used for human consumption and recreation, constituting about 0.3% of surface water sources2. Lakes originate both naturally and artificially. The latter are bodies of water created by excavation in the ground, thanks to human activities such as mining or agriculture3,4. Another type of artificial lake is the so-called reservoir. Forming these is one of the human activities that most modify aquatic ecosystems and is based on damming the waters of a river5. Artificial lakes are mostly created to increase the availability of drinking and irrigation water, generate energy, research, recreation, or as a refuge for wildlife, among others5,6. These types of ecosystems are of great economic and ecological importance. Economically, they favor recreational activities, aquaculture, and agriculture, while ecologically, they favor the reduction of climate change and the formation of natural landscapes as biological reserves7,8,9. However, like any aquatic ecosystem, it also faces environmental problems related to anthropogenic activities. Some of these problems are eutrophication, water pollution, and loss of biodiversity5,9.

The development of various anthropogenic activities around lakes can cause a constant input of pollutants, reducing water quality10. Among these activities, agriculture and its excessive dependence on agrochemicals stand out, causing the lentic ecosystems to be considerably affected11,12. Rice cultivation is one of the main crops globally, a staple in the daily diet, so it contributes greatly to altering aquatic ecosystems13. This alteration is due to the excessive use of agrochemicals in rice fields, releasing an avalanche of elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium14,15. In addition, the release of trace elements such as zinc, cadmium, lead, nickel, and arsenic affect the quality of water and the organisms present16,17.

In this context, applying tools that help verify and confirm water bodies deterioration is essential. In recent years, water quality indices (WQI) have become indispensable tools for assessing the quality of water resources18,19. Using a numerical value, this instrument helps to determine the quality of different water bodies over space and time. The WQI allows the categorization of water quality from “bad” to “good” based mainly on the assessment of physicochemical and biological parameters20. One of the most comprehensive indices, the one proposed by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME-WQI)21. Based on this index, the National Water Authority (ANA) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation of Peru proposed the Water Quality Index of Perú (WQI-PE)22. This instrument, which is the one approved by the Peruvian state to determine water quality, uses three key factors (range, frequency, and magnitude) generating values ranging from 0 to 100, divided into five water quality ranges23.

Lake Burlan, an artificial lake, is one of the main recreational centers in the Amazon region. It is significant for the economic and social development of the district and the protection of biodiversity. Its used as a water source for agricultural activities and its recreational value make it a strategic resource for local development. Burlan Lake was formed by water from the drainage of the neighboring rice fields in the late 1990s24,25. Urbanization, agriculture, and recreational activity have affected the lake’s water quality.

Our research aims to address important knowledge gaps about the physical and chemical characteristics of Burlan Lake. The present investigation sought to determine the water quality of an inter-Andean artificial lake in the northern Peruvian region using the WQI-PE, using limnological parameters and trace elements. At the same time, the spatial and depth variation of limnological parameters and trace elements was determined. Finally, water quality was compared with national and international standards.

Materials and methods

Study area

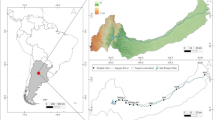

Lake Burlan is located in the district of Bagua Grande, province of Utcubamba in the Amazon region, whose approximate population is 50,000 inhabitants26. It is located at an altitude of 420 m.a.s.l., with coordinates 5°47’13.14” S and 78°22’58.80” W. This lake covers an area of 45.93 hectares and an approximate maximum depth of 8 m25,27. The climate is dry and warm, with an average annual temperature of 25.19 °C and an average annual precipitation of 65.63 mm28. Seasonal variations in temperature and precipitation are moderate; in the dry season, the minimum temperature is 19.58 °C, and the maximum is 30.46 °C, with minimum precipitation of 26.53 mm and maximum precipitation of 45.96 mm. During the wet season, the minimum temperature is 20.21 °C, and the maximum is 30.51 °C, with minimum precipitation of 52.30 mm and maximum of 134.61 mm (Fig. 1).

Location and sampling stations in Lake Burlan. The coordinates of the stations can be found in material supplementary (Supplementary Table S1). The map was created with ArcGIS (version 10.5), using the ArcGoogle tool to integrate the “Google Satellite” base map, while the national, provincial and district boundaries were obtained from the Peruvian National Geographic Institute (IGN) database at a scale of 1:100,000 (https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/limites-departamentales).

The area is noted for the rapid growth of the agricultural frontier, which has created new areas for agriculture and urban development29. The main crop in the area is rice, given that the Amazon region is one of the main rice producers in Peru, with an estimated production of 60,100 tons in 202030. On the other hand, recreational activities such as boating and jet skiing are developed in Lake Burlan and its surroundings. There are also restaurants on the eastern shore of the lake. Other activities include sport fishing for species such as carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver (Menidia sp.), tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) or cashca (Pseudorinelepis genibarbis); and bird watching such as the green kingfisher (Chloroceryle americana), creole duck (Cairina moschata), coot (Fulica sp.)31,32.

Precipitation, along with stationary effluent from rice fields and sewage, constitutes Lake Burlan’s main source of water. Due to its topography, Lake Burlan has limited effluent flow to the southwest. This topographic feature restricts surface water outflow, resulting in water loss through infiltration into the subsoil as recharge of subway aquifers. In addition, natural filtration and biodiversity in the area are critical due to the presence of a 10.3-hectare cattail/wetland zone in the lake.

Methodology used

The zigzag methodology was applied to establish the sampling stations using a west-east direction, given that point SE1 is the deeper point and is close to the wharf33. The stations were previously established in the office phase with the help of QGIS v 3.16 software. They were confirmed in the field with a Garmin Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver, model Oregon 650. The sampling stations were selected considering several criteria: station SE1 was selected because of its maximum depth of 7.8 m and proximity to recreational activities. On the other hand, sampling stations SE2, SE4, SE5, SE6 and SE7 were selected because of their proximity to the rice fields, which discharge their waters into the lake. Finally, station SE3 is characterized by small crop fields other than rice (Fig. 1).

A single sampling was carried out in August 2020 at the seven sampling stations, taking samples at surface level and 1 m depth using a Van Dorne bottle. Water samples were collected in triplicate at each sampling station and by depth. Physicochemical parameters such as pH, temperature (Temp), electrical conductivity (E.C.), dissolved oxygen (DO), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured in triplicate in situ using SI Analytics Handylab 680 multi-parameter equipment at two depths (surface and 1 m).

Process of preservation and transfer of water samples

For the parameters alkalinity (Alka), hardness (Hard), chlorides (Cl-), nitrates (NO3−), nitrites (NO2−), total phosphorus (TP), total solids (TS), ammonium (NH3), sulfates (SO42−), turbidity (Turbi), the samples were preserved and transferred to a 1-liter polyethylene bottle at 4 °C34. In the case of chlorophyll parameters, samples were transferred to a 500 ml amber polyethylene bottle. Finally, for trace element samples, 500 ml polyethylene bottles treated with a 1 M nitrite acid solution at 10% were used for sample storage35.

Sample processing

Sample processing was performed at the Soil and Water Research Laboratory (LABISAG) of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza (UNTRM), accredited under ISO 17025:2017. For alkalinity, hardness and chlorides were determined by titration with hydrochloric acid (HCL), EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and silver nitrate (AgNO3), respectively, applying the methodology of APHA, AWWA AND WEF34. For NO3−, NO2− and TP were determined using the methodology of HACH36. For TS, NH3 y SO42− were determined using the methodology established by APHA, AWWA AND WEF34. For turbidity, a HACH turbidity meter, model 2100Q, was used according to the methodology established by APHA, AWWA and WEF34.

The analysis of chlorophyll a, b, and c was conducted on 47 mm Whatman GF/F glass microfiber filters. The final filter volume was used to determine the chlorophyll content by using 90% acetone, a dark-extracting solvent, following the criteria specified in MAGRAMA37. The concentration of chlorophyll a, b, and c was determined using a Thermo Scientific UV-VIS spectrophotometer, model Genesys 10 S UV-Vis, and the formulas of Jeffrey and Humphrey38, which are widely accepted in the field.

Trace elements such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), mercury (Hg), nickel (Ni), lead (Pb), selenium (Se), zinc (Zn) and barium (Ba) were determined using Atomic Emission Spectroscopy applying the methodology of APHA, AWWA AND WEF34. A microwave plasma atomic emission spectrometer (MP-AES), Agilent Technologies brand, model 4100 MP-AES, equipped with a standard torch, an Inert OneNeb nebulizer and a double-pass glass cyclonic spray chamber was used. To obtain nitrogen from the air required in the process, an Agilent Technologies model Agilent 4107 nitrogen generator was used. The pump speed was set at 15 rpm during the whole process. Before reading the samples, the spectrometer was configured, the consumption time was set to 12 s, the torch stabilization time to 12 s and the rinsing time to 30 s. The reading time used was 5 s. The spectral intensity was determined as the mean of 3 repeated readings per sample to ensure accuracy. The following detection wavelengths were chosen to quantify each element: 193.695 nm for As, 228.802 nm for Cd, 324.754 nm for Cu, 253.652 nm for Hg, 352.454 nm for Ni, 405.781 nm for Pb, 196.026 nm for Se, 213.857 nm for Zn and 455.403 nm for Ba. Before taking the readings, standard solutions of each element at different concentrations were used to calibrate the equipment. The solutions were prepared from a stock solution of 1000 mg/L of Agilent brand in the spectrometry area of LABISAG. After each reading, the equipment recovered the concentration and the intensity without enriching the samples. The detection limits, quantification limits and recovery each element trace it can see in material supplementary (Supplementary Table S2).

Water quality index calculation

The determination of the WQI-PE in Lake Burlan was carried out following the methodology established by the ANA23. It is important to specify that the parameters used to determine the WQI-PE were the following: Chlorophyll a, TP, NH3, DO, pH, ST, SDT, As, Hg, Pb and Zn. These parameters were contrasted with what is established in the Environmental Water Quality Standards (ECA-water) for Category 4: Conservation of the aquatic environment, Subcategory E1: Lakes and lagoons, except for the heavy metal Cd, which was compared with Category 1: Population and Recreational Subcategory A: Surface water intended for the production of drinking water, given that this parameter is not considered in Category 439. It should be taken into account that when only one monitoring is performed per year, the scope is equal to the frequency. To calculate the WQI-PE at each sampling point, Eq. (1) was applied:

Where: WQI-PE: Water quality index Peru. F1: Scope is the ratio between the parameters that do not comply with the ECA-Water to the total number of parameters evaluated. It is calculated using the Eq. (2):

F2: Frequency is the ratio of parameters not complying with the RCT-Water to the total number of parameters evaluated. As there was only one sampling, F1 is equal to F2. F3: Amplitude, which is the ratio of the normalized sum of surplus. It is calculated using the Eq. (3).

Where: NSE: Normalized Sum of Excess. The surplus is the value that represents the difference between the ECA value and the data value concerning the ECA - Water value. It is calculated using the Eq. (4).

GIS mapping procedure

We used ArcGIS 10.5 software (student version) to create the water quality maps of Lake Burlan. WQI-PE data was collected at sampling points (.shp), both at surface level (a) and at one-meter depth (b) according to their respective coordinates (Supplementary Table S1). To create raster surfaces (.tif) with a resolution of 1 m, Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation was employed. As demonstrated in recent studies in other regions40,41, this method provided a detailed representation of the spatial distribution of water quality parameters. The IDW interpolation method is more reliable than other methods, as it is calculated using inverse distance functions in which the opposite distance defines the weights and then normalized so that the sum equals one42.

Development of quality maps

The generated water quality maps were reclassified using the “Reclassify” tool of ArcGIS. This classification was based on the WQI-PE water quality classification proposed by the ANA23 (Supplementary Table S3). The water quality data established by the WQI-PE were assigned to each sampling point for each of the established depths.

Data analysis

Initially, descriptive statistics were used to analyze and describe the essential characteristics of the limnological parameters and trace elements at the two depth levels. The descriptive characteristics include each parameter’s minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation values. Statistical methods were selected using Bartlett’s test of equality of variances and Shapiro-Wilk test of normality. In addition, a two-sample comparison statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test to determine if there are significant differences between depths43.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to identify the most influential variables across spatial and depth parameters and trace elements of the lake44. In this study, PCA was applied to a set of crucial limnological variables and trace elements relevant to water quality and their potential to explain observed differences in the vertical and spatial profile of the lake. The cumulative variance criterion determined the number of principal components to retain. Principal components that together exceed 70% of the total variation of the original variables were retained, ensuring that the most important features of the data were captured.

The graphical representation of the PCA (biplot) can be used to determine relationships between limnological variables and trace elements to better understand the results45. Subsequently, a PERMANOVA was carried out to assess whether the groups defined by the PCA showed significant dissimilar differences. The PERMANOVA detects spatial and depth variations in water based on permutations using Euclidean distance46. All statistical analyses were performed at a significance level of P < 0.05 with R software v. 4.3.147.

The average concentration of trace elements present in the water sample was compared with the Peruvian Environmental Water Quality Standard (ECA), specifically for the category of conservation of the aquatic environment (C4) and the category of extraction and cultivation of hydrobiological species in lakes or lagoons (C2)39; The Canadian Standard for the Protection of Aquatic Life (CCME), established by the Ministers of the Environment48; the U.S. standard established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulations49; and the standard established by the European Union for environmental quality in water policy (EQS)50.

Results

Water quality index WQI-PE

The WQI-PE analysis revealed a value of 43, indicating that Lake Burlan has generally poor water quality. Surface sampling stations SE1, SE2, SE4 and SE5 had poor water quality, in contrast to stations SE3, SE6 and SE7, which had fair water quality. The one-meter depth sampling stations SE1, SE2, SE4 and SE5 had poor water quality, in contrast to stations SE3, SE6 and SE7, which had water of fair quality (Supplementary Table S4). These results suggest no difference in water quality according to depth (Fig. 2). This behavior is confirmed by the Student’s t-test, which found no statistically significant differences in water quality between the surface and 1 m depth (t = 0.857; p = 0.572). However, it is important to note that the average value of WQI-PE was slightly higher at the surface (45) than at 1 m depth (44).

Descriptive statistics of the parameters analyzed at two depths

Alka, TS, NO3−, SO42− variables represent the highest dispersion at the surface level, given their Standard Deviation (SD) values. While, at one meter depth TS, Hard, SO42− and NO3− represent the variable with the highest dispersion. It can be observed that the concentration of Alka, Cl−, NO3−, As and Hg are higher at surface level in contrast to one meter depth, where the value decreases. The opposite is true for Hard, Pb and Se, which are lower at surface level, but increase at a depth of one meter (Table 1).

Spatial stratum variation of all parameters

From the parameters evaluated in the water for both depths, six principal components (PC) were selected, which explained 73.28% of the total variance. The value of each parameter per component was evaluated, considering a strong correlation (r ≥ ± 0.60)51. It is reported that Chl a, Chl b, Chl c, Alka, Cl−, NO3−, Cd are the parameters with the highest significant weight for CP1; for CP2, pH, DO, NO2−, TP, and Zn; for CP3, Temp; for CP4, As; for CP5, Hg; and CP6, Pb (Table 2).

The PCA biplot explained 35.06% of the total variance of the Lake Burlan data. PC1 explained 20.68%, and PC2 explained 14.36% of the data variance. It is observed that the limnological parameters of Chl b, Chl c, Alka, Cl−, NO3− are positively related to Cd and Ni and negatively related to Ba. On the other hand, Chl a, NH3, E.C., and turbi are positively related to Se and negatively related to DO, pH, Hg, and Pb. While As correlates positively with Temp and negatively with Turbi and E.C. Finally, Cu correlates negatively with TS. It is worth mentioning that Zn does not correlate with any limnological variable (Fig. 3).

There are differences in the spatial variation since the ellipses of the stations are not clustered. It is found that SE1 has some influence NO3−, while SE2 has a greater influence on the parameters Chl b, Chl c, Alka, Cd and Cl−, which are strongly positively correlated with each other. Stations SE3 and SE4, do not differ from each other having a greater influence of the parameters Pb, Hg, As, Temp, NO2−, TP, TDS, Hard, DO and pH. It is worth mentioning that TDS and Hard; DO and pH; and TP and NO2−, correlate positively with each other, respectively. SE5 has a more significant influence of the parameters SO42−, Cu, Ba, Zn, Chl a and Se, with only the latter two parameters correlating positively. Stations SE6 and SE7 are grouped; however, the only parameter with some influence in these stations is SO42−. Finally, there is a strong negative correlation between TS and Cu, as well as between Hard and SO42−, and a strong positive correlation between E.C. and Turbi (Fig. 4a). Regarding the variation by depth, no distinct groupings can be distinguished (Fig. 4b).

PERMANOVA analysis of the concentration of limnological parameters and trace elements present in the water indicates significant differences at the spatial level (F = 4.61; p = 0.001), while at the depth level, there are no significant differences (F = 2.42; p = 0.062). Since the p-value is close to 0.05, there could be a trend toward significance. However, it is insufficient to conclude with high confidence that the groups are significantly different.

Comparison of parameters against international and national standards

The average concentration of trace elements in each of the stations according to depth was compared with the national ECA standards, and with the international standards CCME (Canada), EPA (US) and EQS (EU). It is observed that As, Cd, Hg and Pb are above the established limits in most of the sampling stations (Fig. 5). It is worth mentioning that each regulation prioritizes some parameters, such as the EPA regulation, which does not include As or Zn.

Comparison of the averages of: (a) As, (b) Cd, (c) Hg, (d) Pb and (e) Zn, with national and international standards. In (b) the EPA and EQS standards have the same maximum limit of 0.005 mg/L for the element Cd; in (c) the CCME, EQS and ECA standards have the maximum limit of 0.001 mg/L, while the EPA standard doubles this maximum limit (0.002 mg/L); in (d) the ECA standard establishes a maximum limit of 0.0025 mg/L for Pb, which is half the maximum limit indicated by the CCME standard (0.005 mg/L); this is why some of the lines indicating the limits overlap in the figures.

Discussion

Water quality index WQI-PE

The assessment of water quality in Lake Burlan, using nine limnological parameters and five trace elements established by the WQI-PE23, gave an average result of 43 points, which classifies the waters of Lake Burlan in the “poor” quality category. Anthropogenic activities and seasonal variations are determining factors in water quality degradation in lentic ecosystems, as observed in Lake Burlan. Among the anthropogenic activities that most affect water quality are livestock, mining, agriculture, and recreational10. The results obtained in Lake Burlan align with previous studies in other water bodies, both natural and artificial, with similar effects caused by anthropogenic activities. For example, Lake Hawassa in Ethiopia, the Amaluza and Mazar reservoirs in Ecuador, and the Luis León dam in Mexico have been rated between “poor” and “fair” quality categories, mainly due to intensive agriculture and untreated domestic discharges, causing eutrophication problems52,53,54.

Regarding seasonal variations, investigations in Doldi Lake and the twin Tikkar Taal lakes in India have shown that water quality is characterized as “good” or “excellent” during the dry season. In the wet season, with increased rainfall, there is an increase in surface and groundwater flow and runoff, leaching soils and increasing sediment and pollutant load in water bodies, reducing their quality55,56. Likewise, this deterioration is intensified by anthropogenic activities such as recreational or agriculture, causing an increase in total coliforms and chemical oxygen demand (COD)55.

In Lake Burlan, water quality does not currently appear to vary over depth. This agrees with what has been observed in other studies, where no differences in quality are observed at different depths56. However, changes in water quality are evident when different sampling stations are analyzed. In our study, this is evident where stations SE1, SE2, SE4, and SE5 have poor quality, and stations SE3, SE6, and SE7 have fair quality. This behavior occurs at both depths. Given that lake quality is influenced by various factors, both natural and anthropogenic, it is essential to implement urgent measures to mitigate these impacts22. Among these measures is the need to establish preventive monitoring programs, immediate intervention initiatives directed at the source of contamination, and the development of easily applied instruments to know water quality, such as WQI23.

Spatial stratum dynamics of the parameters evaluated in Lake Burlan

Eutrophication in Lake Burlan, as in other freshwater bodies, poses significant ecological challenges due to excessive nutrient enrichment, leading to algal blooms, decreased oxygen levels, and impairment of aquatic life33,57,58. Chl a indicates the state of eutrophication in which aquatic ecosystems are found and the possible human impacts that influence that trophic state. The study’s mean concentration of Chl a varied between 0.0032 and 0.0039 mg/L. This differs from the results obtained in a high Andean lake in northern Peru, Lake Pomacochas, where high concentrations of Chl a were identified during the dry season, influenced by waste from livestock and agricultural activities33. Similarly, Lake Wuli presented high concentrations of Chl a due to agricultural activities, reducing water quality58.

In Lake Burlan, a positive relationship between E.C. and Chl a occurs. The E.C. affects the composition and density of phytoplankton since the higher the EC, the more nutrients can be assumed, increasing Chl a concentration57. On the other hand, Chl a and DO have a negative relationship. Similar results to ours have been seen in studies. It is worth mentioning that DO and Chl a vary with depth, as turbidity limits light penetration, and, thus, the photosynthesis process57,59. This behavior is rooted in temperature, which, when lower, increases DO but limits algae growth60.

The concentration of NH3, NO3−, Pb, Cd, and As in Lake Burlan can be attributed to the influence of agriculture found in the surrounding areas, especially rice crops, which discharge their water into the lake61,62. NO3− and NH3 are present in this type of water, as they are major components of fertilizers, especially NH363. Likewise, due to the need for long periods of flooding to develop rice crops, these waters are contaminated by trace elements related to agrochemicals and become reservoirs of these pollutants64. On the other hand, given the location of the lake in an inter-Andean valley, its presence may also be due to the natural origin of geochemical sources, especially As, a very common element in Andean areas65,66.

In Lake Burlan, high concentrations of trace elements such as Cd, Pb, As, and Hg were found at both depths, but were higher at 1 m depth. For natural water bodies, depth is not a determining factor for contamination, depending more on temporal variations63. However, there can be significant differences in artificial water bodies depending on depth for trace elements such as Ba, Zn, Ni, and Pb due to hydrogeomorphological modifications67. In both cases, it is normal to have a higher concentration of trace elements in the deeper parts of water bodies, especially in sediments. These trace elements can be released back into the water column due to various factors, such as temperature, depth, water movement due to wind or sediment movement due to water input from irrigation canals or streams62. In shallow lakes, there is a risk of high As concentrations in water because As mobilization increases with high temperatures. Temperature can potentially change arsenic release rates from sediments68,69. Although the research did not consider the study of sediments, the study of sediments would strengthen the knowledge of the origin of trace elements in Lake Burlan62,70.

Of note is the negative relationship between TS and Cu in Lake Burlan during the dry season. Most studies mention a positive relationship between these two parameters, especially during the wet season71,72. However, the behavior of these parameters in Lake Burlan may be due to using copper sulfate as fertilizer for the surrounding rice crops73.

Comparison of trace elements with water quality standards

Using national and international standards is justified in evaluating water quality for different uses (human consumption, recreation, agriculture, among others), complementing WQIs74. One of the most widely used WQIs is the one developed by the CCME of Canada, which provides realistic results compared to raw data. Furthermore, it considers all parameters that determine water quality to have the same degree of importance; however, it can only be applied when regulations on water quality parameters are available75. Although the CCME approach requires a laborious process and a robust monitoring network, when combined with a Regional Specific Objective (RSO), it provides a suitable methodology to assess changes in water quality due to prevailing anthropogenic influences in areas near water resources76. To establish the limits of the standards, several studies have been carried out and developed using different WQIs, which have helped identify the levels of contamination in different water bodies77.

When comparing the concentrations of As, Hg, and Pb with national and international standards, they were observed to exceed the limits established by all standards. In the case of Cd, the limits of the Canadian standard are not exceeded, although, in SE2, the limits of all standards are exceeded. Finally, Zn is the only trace element below the limits established by national and international standards. Lake Burlan was characterized by poor water quality according to the WQI-PE, evidenced by the failure to comply with national and international standards by exceeding the established limits. Similar results were obtained in high Andean springs in Peru that presented high levels of As, Sb, and Pb, not complying with the limits established by the WHO and Peruvian standards for both times of the year78.

Non-compliance with national and international standards, and thus poor water quality in Lake Burlan, is mainly due to anthropogenic activities such as agriculture and recreational. These two activities contribute significantly to the overexploitation of water resources, degradation of aquatic ecosystems, acceleration of the eutrophication process, and overall reduction of water quality4,79. To better understand water quality, organic and microbiological parameters should also be included and compared with national and international standards. Anthropogenic activities also influence these parameters since the increase of organic compounds in water, such as thermotolerant coliforms, derived from human and animal feces, or nitrogenous compounds, such as ammonium, cause the increase of chemical oxygen demand and biochemical oxygen demand55. Therefore, future monitoring of Lake Burlan should include these parameters.

Conclusion

Water quality in Lake Burlan is poor to fair, likely attributed to the presence of rice crops in the areas surrounding this lentic ecosystem. The high concentrations of Chl a, NO3−, As, Pb and Hg, mainly due to the use of agrochemicals in the crops, are the causes of the water quality found. This water quality is mainly influenced by spatial variations, but not by variations in depth. For future research, depth profiling should be performed for the most important analytes as a follow-up study. On the other hand, it can be said that the levels of the compared trace elements, As, Hg, Pb and Cd, generally exceed the national and international standards used. It is worth mentioning that these standards establish different levels for the same trace element, so care must be taken when using them. By establishing the pollutants that reach the ecosystem, regional and national environmental authorities can implement restrictive measures and control measures to prevent the continuous impacts to of this water resource by agricultural and recreational activities. In order to continue expanding the knowledge of Lake Burlan, it isnecessary to continue carrying out monitoring that also includes parameters such as DBO5, fats and oils or total coliforms, among others.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wetzel, R. G. Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems (Academic Press Elservier, 2001).

Vasistha, P. & Ganguly, R. Water quality assessment of natural lakes and its importance: An overview. Mater. Today Proc. 32, 544–552 (2020).

Oberholster, P. J., Botha, A. M. & Cloete, T. E. Toxic cyanobacterial blooms in a shallow, artificially mixed urban lake in Colorado, USA. Lakes Reserv. Sci. Policy Manag Sustain. Use 11, 111–123 (2006).

Xu, T. et al. Water quality of Lake Erhai in Southwest China and its projected status in the near future. Water (Switzerland) 16, 972 (2024).

Sotomayor, G. et al. Limnological characteristics and relationships with primary productivity in two high andean hydroelectric reservoirs in ecuador. Water 16, 2012 (2024).

Kazanci, N., Plasa, R. H., Neubert, E. & İzbirak, A. On the limnology of Lake Köycegiz (SW Anatolia). Zool. Middle East. 6, 109–126 (1992).

AbuDalo, M. et al. First assessment of water quality of an artificial lake for fish culture and irrigation: A case study of water reuse in water shortage area across the Middle East. Aquac Res. 52, 1267–1281 (2021).

Al-Khawaldeh, M. A., Al-Habahbeh, O. M., Al-Kasasbeh, R. T. & Al-Adwan, R. S. Mitigating the carbon footprint in Jordan by designing an artificial lake system to improve domestic tourism. Results Eng. 20, 101579 (2023).

Yang, H., Wang, J., Li, J., Zhou, H. & Liu, Z. Modelling impacts of water diversion on water quality in an urban artificial lake. Environ. Pollut. 276, 116694 (2021).

Bhateria, R. & Jain, D. Water quality assessment of lake water: A review. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2, 161–173 (2016).

Lin, Y. et al. Long-term remote sensing monitoring on LUCC around Chaohu Lake with new information of algal bloom and flood submerging. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 102, 102413 (2021).

Qiu, L., Van Dijk, M. P. & Wang, H. Water pollution and environmental governance of the Tai and Chao Lake Basins in China in an international perspective. J. Water Resour. Prot. 07, 830–842 (2015).

Sharma, S., Kaur, I. & Nagpal, A. K. Contamination of rice crop with potentially toxic elements and associated human health risks—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 12282–12299 (2021).

Carlson, R. E. A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 361–369 (1977).

Varol, M. & Tokatlı, C. Impact of paddy fields on water quality of Gala Lake (Turkey): An important migratory bird stopover habitat. Environ. Pollut. 287, 117640 (2021).

Mao, L. et al. Factors controlling the accumulation and ecological risk of trace metal(loid)s in river sediments in agricultural field. Chemosphere. 243, 125359 (2020).

Calvo, S., Romo, S., Soria, J. & Picó, Y. Pesticide contamination in water and sediment of the aquatic systems of the Natural Park of the Albufera of Valencia (Spain) during the rice cultivation period. Sci. Total Environ. 774, 145009 (2021).

Gaytán Alarcón, A. P., González Elizondo, M. S., Vergara Gómez, I., Díaz Lagos, M. & Alarcón Herrera, M. T. Water quality indices in México and Colombia. Evolution, criteria and challenges. Rev. Ing. Investig Y Desarro. 21, 5–22 (2021).

Rana, R. & Ganguly, R. Water quality indices: Challenges and applications—An overview. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 1–11 (2020).

Tyagi, S., Sharma, B., Singh, P. & Dobhal, R. Water quality assessment in terms of water quality index. Am. J. Water Resour. 1, 34–38 (2013).

Dao, V., Urban, W. & Hazra, S. B. Introducing the modification of Canadian Water Quality Index. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 11, 100457 (2020).

Leiva-Tafur, D. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of physicochemical parameters and toxic elements in Lake Pomacochas, Amazonas, Peru. Front. Environ. Sci. 10 (2022).

ANA. Metodología para la determinación del índice de calidad de agua ICA-PE aplicado a los cuerpos de aguas continentales superficiales (Autoridad Nacional del Agua, 2018).

Alva Cruz, R. R. Zonificación Ecológica y Económica del departamento de Amazonas: Evaluación de los recursos turísticos. 64–65 (2010).

Rascón, J. & Corroto, F. Evolución fisicoquímica Y De las bacterias del azufre en microcosmos de diferentes sistemas acuáticos de la Región Amazonas. Tayacaja 3, 25–39 (2020).

INEI. Resultados definitivos censo Región Amazonas (2018).

Maco García, J. Tipos De Ambientes acuáticos De La Amazonía peruana. Folia Amaz. 15, 131–140 (2006).

SENAMHI. Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú. Lima, Perú (2023). http://www.senamhi.gob.pe

Polo Escobar, B. R., Chávez Santos, R. & Mori Ramírez, P. O. Ramírez Carhuatocto, G. Potencialidades Del sector agrario: Condición necesaria en la generación de empleo en la región Amazonas-Perú. Rev. Ciencias Soc. 27, 326–339 (2021).

INEI & Perú Panorama Económico Departamental (2020).

Mincetur. Pertur Amazonas Plan estratégico regional de turismo 2020–2029 (2019).

Rodríguez Achung, F. et al. Zonificación ecológica y económica del departamento de Amazonas 164–165 (2010).

Rascón, J., Corroto, F., Leiva-Tafur, D. & Gamarra Torres, O. A. Variaciones limnológicas espaciotemporales de un lago altoandino tropical Al Norte De Perú. Ecol. Austral 31, 343–356 (2021).

APHA, AWWA & WEF. Standard Methods: For the Examination of Water and Waste Water. (American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation, 2017).

EPA. Method 3050B - Acid digestion of sediments, sludges, and soils. (1996).

HACH. Manual de análisis de agua (HACH COMPANY, 2000).

MAGRAMA. Protocolo de Análisis y Cálculo de Métricas de Fitoplancton en Lagos y Embalses (2013).

Jeffrey, S. W. & Humphrey, G. F. 1New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochem. und Physiol. Der Pflanz. 167, 191–194 (1975).

MINAM. Decreto Supremo N° 004-2017-MINAM. Aprueban Estandares de Calidad Ambiental (ECA) para Agua y establecen disposiciones complementarias (2017).

Khouni, I., Louhichi, G. & Ghrabi, A. Use of GIS based inverse distance weighted interpolation to assess surface water quality: case of Wadi El Bey, Tunisia. Environ. Technol. Innov. 24, 101892 (2021).

Selmane, T., Dougha, M., Djerbouai, S., djemiat, D. & Lemouari, N. Groundwater quality evaluation based on water quality indices (WQI) using GIS: Maadher plain of Hodna, Northern Algeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 30087–30106 (2023).

Ly, S., Charles, C. & Degré, A. Different methods for spatial interpolation of rainfall data for operational hydrology and hydrological modeling at watershed scale. A review. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 17, 392–406 (2013).

Balzarini, M., Di Rienzo, J. & Tablada, M. Introducción A La bioestadística: Aplicaciones con InfoStat (Editorial Brujas, 2013).

Najar, I. A. & Khan, A. B. Assessment of water quality and identification of pollution sources of three lakes in Kashmir, India, using multivariate analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 66, 2367–2378 (2012).

Thioulouse, J. et al. Multivariate analysis of ecological data with ade4. Multivar. Anal. Ecol. Data ade4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8850-1 (2018).

Anderson, M. J. & Walsh, D. C. I. PERMANOVA ANOSIM, and the mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 83, 557–574 (2013).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2023).

CCME. A protocol for the derivation of water quality guidelines for the protection of aquatic life (2007).

EPA. National primary drinking water guidelines (2017).

EU. Directive 2008/105/EC: Water environmental quality standards (2008).

Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish J. Emerg. Med. 18, 91–93 (2018).

Basanta, K., Das & Ebrahim, A. Heavy metals in the water of a developing town of Dhubri District of Assam, India. Int. J. Pharm. Drug Anal. 11, 38–41 (2023).

Rubio-Arias, H., Contreras-Caraveo, M., Quintana, R. M., Saucedo-Teran, R. A. & Pinales-Munguia, A. An overall water quality index (WQI) for a man-made aquatic reservoir in Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 9, 1687–1698 (2012).

Teshome, F. B. Seasonal water quality index and suitability of the water body to designated uses at the eastern catchment of Lake Hawassa. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 279–290 (2020).

Kumar, R., Singh, S. & Sharma, R. C. Application of WQI for assessment of water quality of high altitude lake Dodi Tal, Garhwal Himalaya, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 5, 1033–1042 (2019).

Vasistha, P. & Ganguly, R. Assessment of spatio-temporal variations in lake water body using indexing method. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 41856–41875 (2020).

Lencha, S. M., Tränckner, J. & Dananto, M. Assessing the water quality of lake hawassa Ethiopia—Trophic state and suitability for anthropogenic uses—Applying common water quality indices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18, 8904 (2021).

Wang, J., Fu, Z., Qiao, H. & Liu, F. Assessment of eutrophication and water quality in the estuarine area of Lake Wuli, Lake Taihu, China. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 1392–1402 (2019).

Pizarro, J., Vergara, P. M., Cerda, S. & Briones, D. Cooling and eutrophication of southern Chilean lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 541, 683–691 (2016).

Whitehead, P. G., Wilby, R. L., Battarbee, R. W., Kernan, M. & Wade, A. J. A review of the potential impacts of climate change on surface water quality. Hydrol. Sci. J. 54, 101–123 (2009).

Rashid, A. et al. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: Environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 13, 1521 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Occurrence, risk, and source of heavy metals in lake water columns and sediment cores in Jianghan Plain, Central China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20, 3676 (2023).

Yang, Y., Meng, Z. & Jiao, W. Hydrological and pollution processes in mining area of Fenhe River Basin in China. Environ. Pollut. 234, 743–750 (2018).

Arslan, H. et al. Evaluation of heavy metal contamination and pollution indices through geostatistical methods in groundwater in Bafra Plain, Turkey. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03713-4 (2021).

Arcentales-Ríos, R. et al. Assessment of metals, emerging contaminants, and physicochemical characteristics in the drinking water and wastewater of Cuenca, Ecuador. J. Trace Elem. Min. 2, 100030 (2022).

Ordoñez, O. F. et al. Genome comparison of two Exiguobacterium strains from high altitude andean lakes with different arsenic resistance: Identification and 3D modeling of the Acr3 efflux pump. Front. Environ. Sci. 3, 50 (2015).

Canpolat, Ö., Varol, M., Okan, Ö. Ö., Eriş, K. K. & Çağlar, M. A comparison of trace element concentrations in surface and deep water of the Keban Dam Lake (Turkey) and associated health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 190, 110012 (2020).

Barrett, P. M. et al. Contrasting arsenic cycling in strongly and weakly stratified contaminated lakes: Evidence for temperature control on sediment–water arsenic fluxes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 1333–1346 (2019).

Zeng, L. et al. Temperature and dissolved Oxygen Drive Arsenic mobility at the sediment—Water interface in the Lake Taihu. Toxics 12, 471 (2024).

Mohammed, A., Seid, K. & Woldegbreal, B. Heavy Metals Accumulation in Water and Human Health Risk Assessment via the Consumption of Labeobarbus intermedius Samples from Borkena River, Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 4210574 (2023). (2023).

Beck, H. J. & Birch, G. F. Spatial and temporal variance of metal and suspended solids relationships in urban stormwater-implications for monitoring. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 223, 1005–1015 (2012).

Murillo-Delgado, J. O. et al. Chemical speciation of selected toxic metals and multivariate statistical techniques used to assess water quality of tropical Mexican Lake Chapala. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 418 (2021).

Gamarra-Torres, O. A. et al. 1Fuentes de contaminación estacionales en la cuenca del río Utcubamba, región Amazonas, Perú. Arnaldoa 25, 179–194 (2018).

Gitau, M. W., Chen, J. & Ma, Z. Water Quality indices as tools for decision making and management. Water Resour. Manag. 30, 2591–2610 (2016).

Ismail, A. H. & Robescu, D. Assessment of water quality of the Danube river using water quality indices technique. Environ. Eng. Manag J. 18, 1727–1737 (2019).

de Rosemond, S., Duro, D. C. & Dubé, M. Comparative analysis of regional water quality in Canada using the water quality index. Environ. Monit. Assess. 156, 223–240 (2009).

Tyagi, S., Sharma, B., Singh, P. & Dobhal, R. Water quality assessment in terms of water quality index. Am. J. Water Resour. 1, 34–38 (2020).

Choque-Quispe, D. et al. Insights from water quality of high andean springs for human consumption in Peru. Water (Switzerland) 13, 2650 (2021).

Agustina, A., Aprinica, N. P. I., Muliadiasa, I. K. & Astina, M. A. Construction of kedisan pier to increase tourist visits and water quality in Lake Batur, Bali. J. Pijar Mipa 19, 88–91 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out thanks to the project CUI N° 2262173 “Creación de los Servicios de un Laboratorio para el manejo de Recursos Hídricos en la Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza, región Amazonas” - WATER RESOURCES, and project CUI N° 2590373 “Mejoramiento del Servicio de Promoción de la Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica en el Centro de Investigación para la Conservación y Restauración de Aguas y Suelos “CICRAS” de la UNTRM” executed by the Research Institute for the Sustainable Development of Ceja de Selva (INDES-CES) of the National University Toribio Rodriguez de Mendoza of Amazonas (UNTRM), which were financed by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) of Peru. This research was also financed by the Vice-Rectorate of Research of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas (UNTRM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR: Writing—Original Draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation. LTCR: Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Methodology. SHV: Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Formal Analysis. CSCG: Writing—Review & Editing, Investigation. JCAO: Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition. RSL: Writing—Review & Editing, Conceptualization. JOSL: Writing—Review & Editing, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rascón, J., Cotrina Rioja, L.T., Huaman Vilca, S. et al. Evaluation of the water quality of an artificial inter-andean lake in northern Peru. Sci Rep 14, 23793 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74648-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74648-2