Abstract

Most simulations of electric field driven bioeffects have considered spherical cellular geometries or probed symmetrical structures for simplicity. This work assesses cellular transmembrane potential build-up and electroporation in a Jurkat cell that includes the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, both of which have complex shapes, in response to external nanosecond electric pulses. The simulations are based on a time-domain nodal analysis that incorporates membrane poration utilizing the Smoluchowski model with angular-dependent changes in membrane conductivity. Consistent with prior experimental reports, the simulations show that the ER requires the largest electric field for electroporation, while the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is the easiest membrane to porate. Our results suggest that the experimentally observed increase in intracellular calcium could be due to a calcium induced calcium release (CICR) process that is initiated by outer cell membrane breakdown. Repeated pulsing and/or using multiple electrodes are shown to create a stronger poration. The role of mutual coupling, screening, and proximity effects in bringing about electric field modifications is also probed. Finally, while including greater geometric details might refine predictions, the qualitative trends are expected to remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electroporation (EP) primarily involves the increased permeability of both the outer and the intracellular membranes of biological cells upon exposure to external electric pulses of sufficient duration and intensity1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Studies of electroporation in cells have a long history, and several reports of numerical simulations can be found in the literature11,12,13,14. Other more microscopic treatments that better include the inherent physics of the method have also been discussed15,16,17. The method is an effective non-viral approach for transfection that is independent of cell surface receptors. Other secondary EP induced influences pertain to transport of ions, macromolecules, and genes or drugs for chemotherapeutics18,19,20. Other downstream electric-field induced responses include increases in reactive oxygen species21,22,23,24, capacitive cellular entry of calcium that can disrupt intracellular calcium homeostasis and trigger a cascade of other events25,26,27,28, changes in the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (TMP), opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP)29,30, and adverse effects on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) dynamics. A large influx of Ca2+ after EP can also deplete intracellular ATP and/or inhibit ATP production in mitochondria31. Pulsed electric fields have also been used for cell fusion32, microorganism inactivation33,34, and triggering of immunogenic processes35,36.

Reversible and irreversible EP are the two common modalities. Reversible EP is used to deliver impermeant molecules into cells37,38, and avoid permanent cell damage. Irreversible EP is an efficient ablation modality for treating tumors, especially those unsuitable for surgery or thermal ablation because of their anatomic location39,40. High field electric pulses are also increasingly applied in cardiac ablation to treat arrhythmias41. High-frequency irreversible electroporation (H-FIRE) can effectively treat tumors while mitigating pain and muscle contractions42,43,44,45.

The present study seeks to quantitatively assess the degree of EP at three specific membranes commonly encountered in the cellular structure driven by nanosecond electric pulsing: the cell plasma membrane, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, and the mitochondrial membrane. All three membranes mentioned above control or influence calcium flux, and upon EP could lead to the introduction of supraphysiological concentrations of calcium in cells. Numerical simulations on such aspects have been reported in the literature26,46,47,48. For example, membrane poration would provide a way to induce Ca overload, which has been shown to be a novel cancer treatment modality49. Hence, the ER and the mitochondrion have been included as relevant organelles of interest in this study. Though the nucleus was represented by a sphere inside the ER surface, the process of electroporation in the nucleus was not included. This represents a modest first step and other organelles such as poration at the nucleus, golgi apparatus, etc. could be included in subsequent analyses.

Though calcium ions diffuse freely through pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane under normal homeostasis, their flow across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), requires ion channels or transporters. However, it is quite likely that an external electric field can porate the IMM50, as we recently predicted. Calcium entry could then follow, leading to ATP depletion, which can trigger a cell death pathway. In fact, calcium EP has been proposed as an inexpensive and efficient cancer treatment modality49. Furthermore, many characteristics of tumor cells (e.g., evasion of apoptosis, limitless replication, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, and metastases), are also regulated or altered by calcium51,52.

Despite the conjecture and some promising reports53,54,55, realistic analysis and predictive modeling of EP, including three-dimensional cellular structural geometries and appropriate details of the inherent microstructure, has not been carried out to the best of our knowledge. Most simulations of electric field driven bioeffects, barring a few exceptions56,57,58,59, have relied on spherical cells for simplicity. In biology, spherical shapes are uncommon with protoplasts, murine myeloma cells60, and Streptococcus61 being rare examples of near-symmetric structures. A recent study, however, modeled the buildup of TMPs at the mitochondrion with its two membranes, including random geometric features of the cristae, within a Jurkat50. Here we attempt to go beyond the approximations and simplifications that have been used in the past. The goal is to develop a realistic, physics-based comprehensive simulation for electroporation taking account of a cell with some of its organelles, their realistic shapes, microscopic features such as the mitochondrial cristae, with eventual inclusion of multi-cellular treatments. The present contribution is a modest step in this direction.

The numerical analyses of EP within the ER due to nanosecond electric pulses (NEPs) has been underreported in the literature, though De Angelis et al.62 did report on EP of the endoplasmic reticulum. The utility of ultrashort pulses in penetrating the outer plasma membranes of biological cells and causing EP at organelles was first shown by Schoenbach et al.9 and later expanded to other bioeffects63,64,65. It is thus conceivable that NEPs may be able to cause EP in both the ER and the mitochondrion. Furthermore, since the spatial distance between the ER and the mitochondrion is relatively small, mutual coupling and screening of the internal electric fields are likely to be important and needs to be probed.

In this contribution, we undertake the modest task of predicting the temporal evolution of TMP in response to an externally applied electric pulse. A three-dimensional (3D) structure is utilized for more realistic predictions. Time-dependent calculations using COMSOL were carried out to analyze the spatiotemporal development of the electric fields and the resulting EP at the outer plasma membrane and membranes surrounding the ER, the IMM and OMM. Our predicted results for EP at the ER are also compared to the report by De Angelis62, and exhibit good agreement. The details are discussed in the Results section. We account for changes in the membrane conductivity and the dynamic evolution of pore radii for self-consistency. Details of the simulation method used for the analyses are given next. Thereafter, the results are obtained, and an assessment of the predicted behaviors are presented. Finally, the conclusions, implications, and future research directions are discussed.

Methods

Modeling EP in irregularly shaped cells and/or organelles presents challenges since it requires accounting for the complex geometries and the disparate length scales and curvatures of their features. Any scheme for such a numerical study must be easily amenable to changes in shape, electrode positions, and cell densities, with acceptable accuracy; while allowing user-specified additions in cell number and degree of heterogeneity. Rather than develop analytical electric field models, we used the COMSOL Multiphysics suite to efficiently address these challenges. The generalized field solvers and dynamic meshing in COMSOL facilitate changes in the size or shape of cells or multi-electrode positions without placing heavy computational and analytical burden for each modification. The capability to use any arbitrary geometry would also allow for including data gathered from bio-medical images in future analyses.

As in our previous study50, the self-consistent calculations of EP involved several repetitive steps. First, the spatial distribution of voltage values at a set of discrete nodes within the entire simulation volume was obtained from the field solvers50. This then yielded a spatiotemporal electric field distribution (and hence, the TMPs) that would drive EP. The simulation model was thus based on a distributed circuit representation of a cell, its membrane, the various organelles and surrounding aqueous regions64,66,67,68,69,70. Membrane poration was incorporated by using the Smoluchowski model for time- and angular-dependent changes in membrane conductivity. The membrane conductivity was then updated using the local pore density distributions with details given elsewhere50,71,72.

It may be mentioned that using complete distributions n(ρ,θ,φ,t)73,74,75, which describe pores in four-dimensional space, is computationally intensive. Intricate geometries involving curved surfaces, or double membranes separated by a few nanometers, require fine spatial resolution, which increases the number of grid points, making the full pore-radius dependent calculations through the Smoluchowski equation very time consuming. Consequently, we have applied an asymptotic model of electroporation50,76,77 with a variable membrane tension78,79 to reduce computational expense. The time domain simulations used a 0.1 ns step, with COMSOL’s “Weak Form Boundary PDE” feature to solve the relevant partial differential equations50.

As already discussed, since high levels of cell calcium concentrations can lead to apoptosis80 and given that the ER is a calcium storage site81, it became germane to incorporate an appropriate COMSOL-based model of the ER. For completeness, the presence of mitochondrion as an additional sub-cellular structure was also included into the current analyses, thus enabling an assessment of proximity effects and electric field screening. While the mitochondrial structure with details of the cristae have been implemented and discussed previously50, the geometric construction for the ER requires some discussion. Confocal microscopy has obtained realistic three-dimensional (3D) geometrical representations of ER morphology, with reports of a threshold around 88 kV/cm for significant electroporation in the folds of the ER62. Furthermore, since calcium is mainly stored in the smooth ER82, we primarily focused on accurately modeling the smooth ER.

Blackstone et al.83,84 proposed an ER model consisting of a network of sheets and tubules in which tubules branch off from the surface of the rough ER and extend into a complex network where they intersect and continue branching out into the cell. Figure 1(a) of Goyal and Blackstone84 shows that the rough ER surrounds the nucleus in a series of stacked “sheets”, whereas the tubules come off the surface of the rough ER exterior. The tubules intersect at three-way junctions before branching out into the cell in a complex network. To simplify the geometry to a degree, we disentangled the geometric complexities by only modeling the first layer of smooth ER tubules coming off the surface of the rough ER membrane before the tubules intersect and branch out into the cell. This allowed us to simulate electroporation in the ER tubules without requiring substantial computational resources. The tubules were modeled as cylindrical objects branching off the outer rough ER membrane in a curved shape. Tubule location and orientation were chosen in a pseudo-random manner based on a built-in random function generator to accurately model the branching nature of the tubule structure. Figure 1(a) shows the geometry created to represent this. As shown, many cylindrical tubules branch off a spherical surface representing the outer membrane of the rough ER. Thus, the ER geometry of Fig. 1(a) is similar to that shown in Fig. 1 of Goyal and Blackstone84, without including the inner details or the nucleus sub-areas. Figure 1(b) shows the geometry used to represent the mitochondrion consisting of a double membrane in which the cristae are folded into the inner portion of the organelle.

(a) Smooth ER geometry featuring cylindrical tubules coming off the surface of the rough endoplasmic reticulum. (b) Mitochondrion geometry featuring a double membrane with cylindrical cristae structures extending into the mitochondrion. This figure is similar to that shown previously by our group50.

Previous studies have reported the electrical (including permittivity and conductivity) and physical properties (membrane thickness and size) of the ER and mitochondrion62,84,85,86,87,88. Additionally, there are well established parameters for the electrical characteristics and physical size of typical Jurkat cells89,90,91,92,93 and for the electrical characteristics of typical copper electrodes94. Table 1 provides the values used to model this system.

We modeled the Jurkat cell as an ellipsoid with a major axis of 7 μm and length of 5 μm along the minor axes in the transverse directions50. Cells were placed in a “block” of suspension medium with dimensions of 20 μm × 20 μm × 20 μm. Finally, simulations were performed for each organelle individually and for both organelles together to probe individual and collective effects. In simulations for analysis of the individual ER or the mitochondrion, the organelles were placed at the cell center. For simulations of both organelles, the mitochondrion was offset from the center by 4 μm in the negative x-direction and the ER offset from the center by 2.5 μm in the positive x-direction.

Electroporation experiments have been carried out using needle electrodes95, which enhance local electric fields and thus aid poration. Needle electrodes can penetrate the skin, while also affecting a smaller area of tissue than patch electrodes, which makes them ideal for clinical treatments involving electroporation. Using multiple pairs of needle electrodes also permits sequential pulsing, which leads to a stronger and more uniform electroporation treatment across a larger tissue fraction. In this study, we modeled needle electrode tips by using conductive disks in the suspension medium, and thus our modeling was for in vitro conditions. Figure 2 shows two geometrical needle electrode models developed for the electroporation simulations. The top and bottom electrodes were positive and negative, with the zero node/potential taken to the center of the box. In this context, Neal et al.95 used a much larger electrode diameter than presented here (0.5 mm diameter versus 5 μm diameter). However, the shape is representative and could scale as required. The use of smaller electrodes here, leading to nonuniform electric fields drivers, is of interest in its own right, as local field enhancement can be a desirable feature for augmenting the bio-effects. In this context, the use of bio-compatible nanoparticles in the literature74,96,97 is precisely aimed at the creation of such inhomogeneities and locally enhanced electric fields.

Results

A previous COMSOL-based electroporation study of the ER with structure generated using 3D confocal microscopy62 showed that ~ 88 kV/cm was needed for EP in the folds of the ER. This is rather high compared to experimental work establishing that electroporation can occur at 0.1 kV/cm for larger human cells (e.g., muscle cells), or 1–2 kV/cm for microsecond pulse durations for smaller bacterial cells98,99,100. One might start by expecting the induced TMP (Vmem) to vary with the radius (R) of a spherical bioentity based on the Schwan Eq. 104: Vmem= (3/2) E R cos(θ) [1-exp(-t/τm)], where E is the local electric field, t the time, and τm the membrane charging time which roughly scales as: τm ~ R εm/d, where εm and d are the permittivity and thickness of the membrane102,103. Hence, at very small times Vmem~ (3/2) E cos(θ) {(t d)/εm}. However, such a simplified analysis could be inaccurate since it is based on the following assumptions: (i) Near zero membrane conductivities102, (ii) a spherical shape for the cell and all its organelles, and (iii) a concentric structure as has often been assumed104. In reality, analytic formulations are not possible, especially with non-spherical structures that are positioned off-center. Furthermore, the geometric intricacies and potential shielding by other organelles and cells can alter simple-minded relationships. Only finite-element based numerical analyses, as done here, can furnish a correct solution. Also, it may be mentioned that we were not aiming for a match with actual experiments, but rather to look for similar qualitative trends. Given that many aspects of the overall complicated cell structure were not included in the present model, one cannot hope to get a close comparison to mimic a real experiment. Nonetheless, our contribution pushes the boundaries for modeling, and we will aim for even more realistic simulations in the future.

Previous experiments27 have shown that the mitochondrial electroporative response depends on the rise-time of the applied pulse. This was hypothesized to arise from the higher displacement currents associated with a faster rising electric pulse. Other reports also indicate similar pulse-dependent bio-outcomes105. Our prior modeling established that nanosecond excitation could rapidly induce large TMPs in the mitochondrion50. Here for the simulations, we chose a 100 ns pulse with 20 ns rise and fall times and a 60 ns ON-time for the field stimulus.

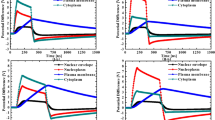

We first discuss EP of a Jurkat cell containing a mitochondrion and the ER. For these simulations, one pair of electrodes was pulsed using a 100 ns pulse-width (as discussed above) for applied fields of 25 kV/cm, 75 kV/cm, and 125 kV/cm. TMP was then taken at a point on each surface normal to the applied electric field to ensure consistency in the calculations. Figure 3 shows the time-dependent TMP over a 150 ns duration at four locations: (i) the inner mitochondrial membrane (TMP-IMM), (ii) the outer mitochondrial membrane (TMP-OMM), (iii) the cell membrane (TMP-CM), and (iv) the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (TMP-ER).

Evolution of the transmembrane potential (TMP) in Volts over a 150 ns duration for points on the surface of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), cell membrane (CM), and the ER membrane (ER), with all points taken normal to the applied fields. (a) Points along the geometry that were chosen. Results for electric fields of (b) 25 kV/cm, (c) 75 kV/cm, and (d) 125 kV/cm.

The reduction in TMP of the cell membrane (CM) at ~ 0.0375 µs during the 25 kV/cm field in Fig. 3(b) indicates the onset of poration, which corresponds to the effective membrane shorting. The IMM exhibits a slight onset of EP earlier at ~ 0.03 µs with an imperceptible dip in the TMP. However, the growth and poration rates are small; hence, the TMP remains nearly flat until the pulse begins to turn off at 0.08 µs. In comparison, the OMM and the ER membranes do not porate at 25 kV/cm. For the 75 kV/cm case [Fig. 3(c)], the CM exhibits a stronger EP characteristic with a sharper fall-off in the TMP starting at ~ 0.022 µs, after an overshoot up to ~ 2.2 V. Furthermore, the TMP of the IMM increases sharply and begins to fall as EP begins. The IMM response is predicted to be faster than the CM characteristic. Additionally, the OMM exhibits signs of EP with a reduction in TMP at ~ 0.022 µs, similar in time to the dynamic onset at the CM. These results qualitatively agree with experimental observations of reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential in Jurkat cells30. However, an important distinction between possible indications of electroporation based on measured data and the simulation results reported here needs to be clarified. Here, the only quantity being tracked and predicted is the time-dependent variation in TMP values. A flattening of such a curve, or even a negative slope over certain time intervals, only points to possible poration at the local level. The pore formation, however, may be small in terms of its density, or the total area, and thus might not have tangible effects on measurable molecular transport. For example, the outflows of ions or the uptake of molecules such as propidium iodide (PI), which is a common marker for poration, might not be picked up in experiments. Furthermore, given the time needed for motion and flow in or out of cells, nothing would likely be discerned over one or even a few nanosecond pulses. Finally, cellular response could even occur after an initial strong pulse as has recently been shown by Asadipour et al.106, or might require a train of multiple pulses.

Moreover, experimental results30 could not definitively conclude whether the nanosecond electric pulses induced decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential resulted from the direct electroporation of the inner mitochondrial membrane, the formation of mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pores, or from some other permeabilization mechanism. However, mitochondrial poration could be a likely cause. The ER, however, is predicted to undergo negligible poration despite the higher 75 kV/cm field. At 125 kV/cm, ER is predicted to reach a TMP greater than 1 V, which most likely corresponds to the cusp of EP initiation107,108. However, the TMP does not appear to decrease much (or perhaps the effect is masked by the start of the pulse decay). This result is on the same order of magnitude as a previous report62, indicating that the EP threshold for the ER is much higher. Our result could loosely be compared with a report by De Angelis et al.62. They reported TMP at the ER crossing the poration threshold of 1 V at an externally applied electric field of 130 kV/cm. Here, we predict similar results for electric fields of 125 kV/cm. It should be kept in mind, however, that the simulation reported by De Angelis et al.62 did not account for the complicated three-dimensional geometry that we employ in the present calculations. The present result, however, is indirectly suggestive of the observed calcium release process in cells subjected to external electric pulsing109,110,111. Since the ER itself is not likely to be easily porated, the observed increase in cellular calcium might arise from plasma membrane poration, possibly followed by CICR.

Next, the mitochondrion and ER were simulated separately inside a Jurkat cell at a 75 kV/cm field to study the EP response of each organelle. For these studies, each organelle was placed in the center of the cell and the needle electrode geometry [cf., Fig. 2(a)]. A stimulus in the z-dimension applied for the single pulse case, while the three-electrode pair geometry [cf., Fig. 2(b)] was chosen for applying a pulse in the x, y, and z dimensions for the three sequential pulsing case. Simulation results for the local electric field developed in the IMM [Fig. 4(a)], and on the OMM surface [Fig. 4(b)] are shown. The applied field was taken to be along the z-axis. The associated voltage profile at 50 ns (midway through the 100 ns applied pulse) is shown in Fig. 5(a), while Fig. 5(b) gives the electric field magnitudes with finer resolution in the y-z plane. Figure 4(a) shows that field enhancement occurs at the tips of the mitochondrial cristae normal to the applied field. The high fields occur only at the cristae tips for structures oriented along the z-direction, but much lower fields occur at cristae that are otherwise aligned. Furthermore, the electric field decreases slightly near the polar caps at the top and bottom surfaces of the mitochondrion in Fig. 4(b). As we show later, this occurs due to strong electroporation at these regions that leads to electrical shorting. The cross-sectional view of the voltage profile in Fig. 5(a) reveals large gradients at the cristae tip pointing along the z-axis. In Fig. 5(b), the field collapse in the IMM cristae is not predicted to be as large. This is due to the smaller size of the cristae, which does not translate into a large porated area.

Applying multiple pulses can be expected to induce additional effects. For probing this situation, we considered three sequential 100 ns, 75 kV/cm pulses along the z-, x-, and y-directions of a mitochondrion, respectively. A 50 ns snapshot of the internal field on the IMM surface in Fig. 6(a) is identical to the snapshot in Fig. 4(a). Figure 6(b) and 6(c) show the field after 150 ns and 250 ns. Each successive applied pulse is seen to increase the electric fields. Here it may be mentioned that repetition rates in practice tend to be somewhat lower than used here. For example, typical application of bipolar pulses in the H-FIRE protocol could involve a 2 µs – 5 µs – 2 µs burst repeated until 100 µs of on-time, with about a 5 µs delay between pulses39,43,45. Another slightly higher repetition rate was used by Kiełbik et al.112, while Pakhomov et al.113, applied repetition rates of up to 4 MHz, which translate into a time scale of 0.25 µs. Here, our value at 0.1 µs is shorter, but not by a large amount.

Figure 7(a) and Fig. 7(b) show simulated pore densities (on a logarithmic scale) for a single pulse [along the z-axis as in Fig. 4(a)] and a sequence of three successive non-overlapping pulses applied along the z-, x- and y- directions, respectively, at the 300 ns time instant. As expected, a single pulse along the z-axis induces the highest poration at the polar caps with levels reaching above 1016 m− 2. The remaining regions are comparatively less porated with densities from 109 to 1012 m− 2. Figure 7(b) predicts that applying three successive pulses can cause both substantially higher pore formation and more uniform poration throughout the organelle compared to a single pulse. This ability to reach different regions and spatial positions through repetitive pulsing is critical for cancer treatments, which require affecting the entire tumor volume. Studies of repetitive pulsing, clever electrode geometries, and multi-pronged applicators114,115 have indicated that multi-pronged electrode configurations and judicious pulse sequencing would enhance the degree of cellular uptake.

A similar trend of more effective TMP build-up also occurred in the ER. We simulated an ER exposed to a single 100 ns, 75 kV/cm pulse along the z-direction, and then three non-overlapping successive 100 ns, 75 kV/cm pulses applied along the z-, x-, and y- axes (as assessed for the mitochondrion). Figure 8 shows the electric field on the surface of the ER after 50 ns due to the single pulse. The field is highest in a ring near the “poles” of the ER membrane (at the top and bottom of the ER) with respect to the z-axis, indicating poration at these locations. However, the complex cylindrical structure of the tubules makes it difficult for high fields to build up within these sub-structures, and hence, the electric fields in the tubules generally lower than at the membrane surface. This indicates the difficulty in reaching a critical TMP in the ER tubules.

Previous studies observed that high applied fields were required to porate the complicated tubular structures of the ER62. Figure 9(a) shows a logarithmic pore density profile on the ER surface after 300 ns following the start of a single 100 ns, 75 kV/cm applied pulse; Fig. 9(b) assesses portion for three, non-overlapping successive 100 ns, 75 kV/cm pulses. As with the mitochondrion, greater pore formation was predicted across membranes for sequential pulses applied in the three mutually orthogonal directions than with a single pulse alone. Furthermore, less poration was predicted in the tubules than on the surface of the ER membrane, due to the complex structure and bends in the tubules.

Progressing toward adequately modeling electroporation dynamics in a full cell requires placing organelles close to one another. This naturally raises the issue of mutual coupling, and the possibility of electric field modifications due to screening effects. To probe this aspect, a comprehensive calculation was carried out with both the mitochondrion and the ER placed together in a Jurkat cell and exposed to three sequential 100 ns, 75 kV/cm pulses applied along the z-, x-, and y- axes. Figure 10 shows the simulated pore density on a logarithmic scale. As expected, screening occurs between the organelles, which reduces the poration over portions of the cell that have the ER and mitochondrion lying near each other. The greatest poration, on the other hand, is predicted to occur on the membrane surfaces of each organelle along the common axes that are closest to the electrodes. Furthermore, very low pore formation is predicted in the smooth ER, in keeping with previous results.

In this context, it may be mentioned that electrical stimulation is usually used for targeted killing of tumor cells. Thus, instead of a single cell, one would typically have a collection of cells, or part of a diseased tissue or organ. In such a situation, it becomes imperative to ensure that the entire tumor mass is effectively treated by the electrical exposure. So then, use of multiple pulsing at a fixed location might not be optimal since the same localized spot would continually be getting treated. If the electrical stimulation was being used for electrochemotherapy, it would be more advantageous to porate and ensure drug uptake from different sides and regions of the affected tissue/organ. This was the reason and essence behind choosing the different orientations in our simulations. Obviously, for a more realistic and meaningful analysis, at least a multi-cell, multi-pronged analysis would become necessary. Use could also be made of nanoparticles that function as distributed electrodes for better and more efficient outcomes68,116.

We note that placing both organelles inside the cell necessitated offsetting each from the cell center for positional accommodation. This put each organelle at a slightly different distance from the straight path joining the centers of the electrode pair oriented in the x-y plane. As a result, the ER remained unaffected along the y- and z- directions, with the electric fields from both pairs of electrodes in the x-z and y-z planes threading between the organelles. The mitochondrion was less affected by the location shift, most likely due to its smaller size. In any event, Fig. 10 shows that screening occurs with lower poration predicted over regions of the surfaces where the ER and mitochondrion face each other. Finally, the mitochondrion exhibits a more well-rounded overall pore density over the entire surface, whereas the ER would likely have a small EP patch only over a small region furthest removed from the mitochondrion and in closest proximity to an electrode.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, simulation work at probing time-dependent electroporation via nanosecond pulses in a cancer cell with inclusion of organelles such as the ER and mitochondrion has not been reported in the literature. This aspect represents a new feature. Next, both the ER and mitochondrion are entities that have connections to calcium. The ER has an abundant supply of calcium that could load a cell via electroporation. On the other hand, increased calcium levels are critical to the mitochondria and can trigger cell death. Since the cellular calcium concentrations can be modulated by electroporative means, such modeling becomes technologically important via the calcium connection. Novel cancer modalities based on “calcium electroporation” have already been studied49. Based on such simulation work, optimizing parameters to efficiently kill tumor cells could be envisioned, and would have a very positive impact in biomedical engineering and bio-physics based cancer treatment.

Most simulations of electric field driven bioeffects, barring a few exceptions56,57,58,59, have used spherical cellular geometries or simple symmetrical structures for simplicity. However, realistically assessing cellular responses, especially including organelles with complex shapes such as the ER and mitochondria, make simple representations grossly inadequate. The present contribution takes a modest first step towards realistic numerical studies of a single cell containing multiple sub-cellular organelles with complex geometric structures, which can be extended and incorporate more organelles including details of electroporation at the nucleus, the golgi apparatus etc. We chose NEPs because they have been hypothesized to allow for electric field penetration into cells to affect organelles. A simulation technique based on a time-domain nodal analysis that incorporates membrane poration utilizing the Smoluchowski model with angular-dependent change in membrane conductivity was used. Details of the geometric structures of the ER and mitochondria were included.

The present calculations led to the following results/predictions: (i) The relative electric field thresholds for membrane poration at the cell membrane, the IMM and OMM, and the membranes of the smooth ER were all determined. Of these, the ER required the largest field for possible electroporation. (ii) Simulation results obtained here show that it is much easier to porate the cell membrane than the ER membrane, suggesting that the experimentally observed increases in intracellular calcium could likely result from the CICR process initiated by the breakdown of the cell membrane. Previous reports conjectured that ER membrane poration might directly cause the experimentally observed increases in cellular calcium66,110. However, our results support CICR. (iii) The present simulation results show that mitochondrial poration can occur at about the same (or slightly lower) applied fields than the plasma membrane. Of the two membranes, the IMM was predicted to porate more easily than the OMM, in line with previous experimental trends27. (iv) Multiple pulsing was probed to evaluate possible advantages for killing tumors in tissues (particularly in a larger volume). A single electrode (or prong) or individual pulse was shown to have a limited effect. We determined that applying three non-overlapping pulses in three mutually orthogonal directions induced stronger TMP build-up than a single pulse for both the ER and the mitochondrion. This supports the hypothesis that multi-pronged electrode applicators can maximize therapeutic benefits114. While the studies by Heller at al.114,115 employed needles of larger diameter, the inherent physics remains the same though some quantitative differences may possibly arise. In any event, here we have similarly shown the advantage of multi-pronged electrode applicators through simulations. (v) Screening and mutual coupling was studied through comprehensive simulations of both the smooth ER and the mitochondrion in a Jurkat cell. The electric field modifications led to highly nonuniform development of the TMP. The regions near and facing the external electrodes developed the largest TMP, while regions of individual organelles lying close to each other had lower TMPs. This demonstrated the spatial nonuniformities inherent in creating the electric fields and resulting variations in the degree of bioeffects. This also underscored the importance of applying multiple pulses, either simultaneously or in a non-overlapping manner, with electrodes distributed spatially to maximize the desired effects and improve treatment efficacy of electroporation. While more compete models may change the details of these simulations, the general trends would remain since all relevant biophysics has been included here.

As a final note, possible improvements and further use of our work in bioengineering could be carried out to include a number of additional features. The basic continuum analysis that hinges on an approach employing the Smoluchowski theory with self-consistent electric field calculations would continue to apply. However, extensions could include: (i) adding other organelles (e.g., including details of electroporation at the nucleus, the golgi apparatus, etc.), (ii) including ion flow, (iii) increasing the scope to probe tissues rather than a single cell, (iv) coupling local heating, as was done in one of our previous contributions66, (v) taking data made available from actual discretized images to refine the accuracy of geometric structures used in the calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kinosita, K. & Tsong, T. Y. Voltage-induced pore formation and hemolysis of human erythrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 471, 227–242 (1977).

Zimmermann, U. Electric field-mediated fusion and related electrical phenomena. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Biomembr. 694, 227–277 (1982).

Arnold, W. M. & Zimmermann, U. Electric field-induced fusion and rotation of cells. In Biological Membranes 389–454 (1984).

Neumann, E. & Rosenheck, K. Permeability changes induced by electric impulses in vesicular membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 10, 279–290 (1972).

Mir, L. et al. Electrochemotherapy, a new antitumor treatment: first clinical trial. C. R. Acad. Sci. 313, 613–618 (1991).

Kotnik, T., Rems, L., Tarek, M. & Miklavčič, D. Membrane electroporation and electropermeabilization: mechanisms and models. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 48, 63–91 (2019).

Chizmadzhev, Y. A., Arakelyan, V. B. & Pastuhenko, V. F. Electric breakdown of bilayer lipid membranes. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 104, 63–70 (1979).

Hibino, M., Shigemori, M., Itoh, H., Nagayama, K. & Kinosita, K. Membrane conductance of an electroporated cell analyzed by submicrosecond imaging of transmembrane potential. Biophys. J. 59, 209–220 (1991).

Schoenbach, K. H., Beebe, S. J. & Buescher, E. S. Intracellular effect of ultrashort electrical pulses. Bioelectromagnetics 22, 440–448 (2001).

Wilhelm, C., Winterhalter, M., Zimmermann, U. & Benz, R. Kinetics of pore size during irreversible electrical breakdown of lipid bilayer membranes. Biophys. J. 64, 121–128 (1993).

Gowrishankar, T. R., Esser, A. T., Vasilkoski, A., Smith, K. C. & Weaaver, J. C. Microdosimetry for conventional and supra-electroporation in cells with organelles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 341, 1266–1276 (2006).

Smith, K. C., Gowrishankar, T. R., Esser, A. T., Stewart, D. A. & Weaver, J. C. The spatially distributed dynamic transmembrane voltage of cells and organelles due to 10 ns pulses: meshed transport networks. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 34, 1394–1404 (2006).

Esser, A. T., Smith, K. C., Gowrishankar, T. R., Vasilkoski, Z. & Weaver, J. C. Mechanisms for the intracellular manipulation of organelles by conventional electroporation. Biophys. J. 98, 2506–2514 (2010).

Retelj, L., Pucihar, G. & Miklavcic, D. Electroporation of intracellular liposomes using nanosecond electric pulses-A theoretical study. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60, 2624–2635 (2013).

Ho, M. C., Levine, Z. A. & Vernier, P. T. Nanoscale, electric field-driven water bridges in vacuum gaps and lipid bilayers. J. Membr. Biol. 246, 793–801 (2013).

Böckmann, R. A., de Groot, B. L., Kakorin, S., Neumann, E. & Grubmüller, H. Kinetics, statistics, and energetics of lipid membrane electroporation studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 95, 1837–1850 (2008).

Marracino, P. et al. Electric-driven membrane poration: a rationale for water role in the kinetics of pore formation. Bioelectrochemistry 143, 107987 (2022).

Neumann, E., Schaefer-Ridder, M., Wang, Y. & Hofschneider, P. H. Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by electroporation in high electric fields. EMBO J. 1, 841–845 (1982).

Okino, M. & Mohri, H. Effects of a high-voltage electrical impulse and an anticancer drug on in vivo growing tumors. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 78, 1319–1321 (1987).

Mir, L. M., Orlowski, S., Belehradek, J. & Paoletti, C. Electrochemotherapy potentiation of antitumour effect of bleomycin by local electric pulses. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 27, 68–72 (1991).

Gabriel, B. & Teissié, J. Generation of reactive-oxygen species induced by electropermeabilization of Chinese hamster ovary cells and their consequence on cell viability. Eur. J. Biochem. 223, 25–33 (1994).

Breton, M. & Mir, L. M. Investigation of the chemical mechanisms involved in the electropulsation of membranes at the molecular level. Bioelectrochemistry 119, 76–83 (2018).

Szlasa, W. et al. Oxidative effects during irreversible electroporation of melanoma cells—in vitro study. Molecules 26, 154 (2021).

Pakhomova, O. N. et al. Oxidative effects of nanosecond pulsed electric field exposure in cells and cell-free media. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 527, 55–64 (2012).

Putney, J. W. Capacitative calcium entry: sensing the calcium stores. J. Cell Biol. 169, 381–382 (2005).

Berridge, M. J., Bootman, M. D. & Roderick, H. L. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 517–529 (2003).

Beebe, S. J., Chen, Y. J., Sain, N. M., Schoenbach, K. H. & Xiao, S. Transient features in nanosecond pulsed electric fields differentially modulate mitochondria and viability. PLoS ONE 7, e51349 (2012).

Pakhomova, O. N., Gregory, B., Semenov, I. & Pakhomov, A. G. Calcium-mediated pore expansion and cell death following nanoelectroporation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1838, 2547–2554 (2014).

Beebe, S. J. Considering effects of nanosecond pulsed electric fields on proteins. Bioelectrochemistry 103, 52–59 (2015).

Napotnik, T. B., Wu, Y., Gundersen, M. A., Miklavčič, D. & Vernier, P. T. Nanosecond electric pulses cause mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in Jurkat cells. Bioelectromagnetics 33, 257–264 (2011).

Hansen, E. L. et al. Dose-dependent ATP depletion and cancer cell death following calcium electroporation, relative effect of calcium concentration and electric field strength. PLoS ONE 10, 122973 (2015).

Jordan, C. A., Neumann, E. & Sowers, A. E. Electroporation and Electrofusion in Cell Biology (Springer, 2013).

Garner, A. L. Pulsed electric field inactivation of microorganisms: from fundamental biophysics to synergistic treatments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 7917–7929 (2019).

Schoenbach, K. H., Joshi, R. P., Stark, R. H., Dobbs, F. C. & Beebe, S. J. Bacterial decontamination of liquids with pulsed electric fields. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 7, 637–645 (2000).

Go, E. J. et al. Combination of irreversible electroporation and STING agonist for effective cancer immunotherapy. Cancers 12, 3123 (2020).

McDaniel, A. et al. Nano-pulse stimulation TM therapy (NPSTM) is superior to cryoablation in clearing murine melanoma tumors. Front. Oncol. 12, 948472 (2023).

Campana, L. G. et al. Electrochemotherapy – emerging applications technical advances, new indications, combined approaches, and multi-institutional collaboration. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 45, 92–102 (2019).

Lambricht, L. et al. Clinical potential of electroporation for gene therapy and DNA vaccine delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13, 295–310 (2015).

Geboers, B. et al. Meijerink. M. R. High-voltage electrical pulses in oncology: irreversible electroporation, electrochemotherapy, gene electrotransfer, electrofusion, and electroimmunotherapy. Radiology 295, 254–272 (2020).

Sugrue, A. et al. Irreversible electroporation for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 16, 349–360 (2018).

Bradley, C. J. & Haines, D. E. Pulsed field ablation for pulmonary vein isolation in the treatment of atrial fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophys. 31, 2136–2147 (2020).

Arena, C. B. et al. High-frequency irreversible electroporation (H-fire) for non-thermal ablation without muscle contraction. Biomed. Eng. Online 10, 102 (2011).

O’Brien, T. J. et al. Experimental high-frequency irreversible electroporation using a single-needle delivery approach for nonthermal pancreatic ablation in vivo. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 30, 854–862 (2019).

Sano, M. B. et al. V. bursts of bipolar microsecond pulses inhibit tumor growth. Sci. Rep. 5, 14999 (2015).

Ringel-Scaia, V. M. et al. High-frequency irreversible electroporation is an effective tumor ablation strategy that induces immunologic cell death and promotes systemic anti-tumor immunity. EBioMedicine 44, 112-125 (2019).

Carafoli, E. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 1115–1122 (2002).

Bootman, M. D., Berridge, M. J. & Lipp, P. Cooking with calcium: the recipes for composing global signals from elementary events. Cell 91, 367–373 (1997).

Berridge, M. J., Bootman, M. D. & Lipp, P. Calcium—a life and death signal. Nature 395, 645–648 (1998).

Frandsen, S. K., Vissing, M. & Gehl J. A. comprehensive review of calcium electroporation—a novel cancer treatment modality. Cancers 12, 290 (2020).

Milestone, W., Baker, C., Garner, A. L. & Joshi, R. P. Electroporation from mitochondria to cell clusters: model development toward analyzing electrically driven bioeffects over a large spatial range. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 244701 (2023).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100, 57–70 (2000).

Prevarskaya, N., Ouadid-Ahidouch, H., Skryma, R. & Shuba, Y. Remodelling of Ca2+ transport in cancer: how it contributes to cancer hallmarks? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130097 (2014).

Staresinic, B. et al. Effect of calcium electroporation on tumour vasculature. Sci. Rep. 8, 9412 (2018).

Frandsen, S. K., Gibot, L., Madi, M., Gehl, J. & Rols, M. P. Calcium electroporation: evidence for differential effects in normal and malignant cell lines, evaluated in a 3D spheroid model. PLoS ONE 10, 0144028 (2015).

Falk, H. et al. Calcium electroporation induces tumor eradication, long-lasting immunity and cytokine responses in the CT26 colon cancer mouse model. OncoImmunology 6, e1301332 (2017).

Kotnik, T. & Miklavčič, D. Analytical description of transmembrane voltage induced by electric fields on spheroidal cells. Biophys. J. 79, 670–679 (2000).

Bernhardt, J. & Pauly, H. On the generation of potential differences across the membranes of ellipsoidal cells in an alternating electrical field. Biophysik 10, 89–98 (1973).

Nath, S., Sinha, K. P. & Thaokar, R. M. Development of transmembrane potential in concentric spherical, confocal spheroidal, and bispherical vesicles subjected to nanosecond-pulse electric field. Phys. Rev. E 101, 062407 (2020).

Pucihar, G., Kotnik, T., Valič, B. & Miklavčič, D. Numerical determination of transmembrane voltage induced on irregularly shaped cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 34, 642–652 (2006).

Gimsa, J. & Wachner, D. A polarization model overcoming the geometric restrictions of the laplace solution for spheroidal cells: obtaining new equations for field-induced forces and transmembrane potential. Biophys. J. 77, 1316–1326 (1999).

Batzing, B. L. Microbiology: An Introduction (Thompson Learning, 2002).

De Angelis, A. et al. Liberti. M, confocal microscopy improves 3D microdosimetry applied to nanoporation experiments targeting endoplasmic reticulum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 552261 (2020).

Beebe, S. J., Joshi, R. P., Schoenbach, K. H. & Xiao, S. Ultrashort Electric Pulse Effects in Biology and Medicine (Springer, 2021).

Joshi, R. P. & Schoenbach, K. H. Bioelectric effects of intense ultrashort pulses. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 38, 255–304 (2010).

Joshi, R. P. & Schoenbach, K. H. Electric fields in biological cell and membranes. In Electromagnetic Fields in Biological Systems 71–114 (CRC Press, 2011).

Milestone, W., Hu, Q., Loveless, A. M., Garner, A. L. & Joshi, R. P. Modeling coupled single cell electroporation and thermal effects from nanosecond electric pulse trains. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 094701 (2022).

Joshi, R. P. & Hu, Q. Analysis of cell membrane permeabilization mechanics and pore shape due to ultrashort electrical pulsing. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 48, 837–844 (2010).

Milestone, W., Hu, Q., Garner, A. L. & Joshi, R. P. Sinusoidal RF simulations for optimized electroporation protocols. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 174702 (2023).

Hu, Q. et al. Simulations of transient membrane behavior in cells subjected to a high-intensity ultrashort electric pulse. Phys. Rev. E 71, 031914 (2005).

Joshi, R. P., Hu, Q. & Schoenbach, K. H. Modeling studies of cell response to ultrashort, high-intensity electric fields—implications for intracellular manipulation. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 32, 1677–1686 (2004).

Neu, J. C. & Krassowska, W. Asymptotic model of electroporation. Phys. Rev. E 59, 3471–3482 (1999).

Neu, J. C. & Krassowska, W. Modeling postshock evolution of large electropores. Phys. Rev. E 67, 021915 (2003).

Hu, Q. & Joshi, R. P. Transmembrane voltage analyses in spheroidal cells in response to an intense ultrashort electrical pulse. Phys. Rev. E 79, 011901 (2009).

Hu, Q. & Joshi, R. P. Continuum analysis to assess field enhancements for tailoring electroporation driven by monopolar or bipolar pulsing based on nonuniformly distributed nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. E 103, 022402 (2021).

Joshi, R. P., Song, J. & Sridhara, V. Aspects of lipid membrane bio-responses to subnanosecond, ultrahigh voltage pulsing. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 16, 1243–1250 (2009).

Krassowska, W. & Filev, P. D. Modeling electroporation in a single cell. Biophys. J. 92, 404–417 (2007).

DeBruin, K. A. & Krassowska, W. Modeling electroporation in a single cell. I. effects of field strength and rest potential. Biophys. J. 77, 1213–1224 (1999).

Mukherjee, P., Nathamgari, S. S. P., Kessler, A. & Espinosa, H. D. Combined numerical and experimental investigation of localized electroporation-based cell transfection and sampling. ACS Nano 12, 12118-12128 (2018).

Neu, W. K. & Neu, J. C. Theory of electroporation. In Cardiac Bioelectric Therapy 133–161 (Springer, 2009).

Orrenius, S., McCabe, M. J. & Nicotera, P. Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of cytotoxicity and programmed cell death. Toxicol. Lett. 64–65, 357–364 (1992).

Koch, G. L. The endoplasmic reticulum and calcium storage. BioEssays 12, 527–531 (1990).

Bardo, S., Cavazzini, M. G. & Emptage, N. The role of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store in the plasticity of central neurons. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 78–84 (2006).

Park, S. H. & Blackstone, C. Further assembly required: construction and dynamics of the endoplasmic reticulum network. EMBO Rep. 11, 515–521 (2010).

Goyal, U. & Blackstone, C. Untangling the web: mechanisms underlying ER network formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 1833, 2492–2498 (2013).

Qiu, H., Xiao, S. & Joshi, R. P. Simulations of voltage transients across intracellular mitochondrial membranes due to nanosecond electrical pulses. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 42, 3113–3120 (2014).

Schwarz, D. S. & Blower, M. D. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 79–94 (2015).

Joubert, F. & Puff, N. Mitochondrial cristae architecture and functions: lessons from minimal model systems. Membranes 11, 465 (2021).

Mitra, K., Ubarretxena-Belandia, I., Taguchi, T., Warren, G. & Engelman, D. M. Modulation of the bilayer thickness of exocytic pathway membranes by membrane proteins rather than cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 4083–4088 (2004).

Denzi, A. et al. Assessment of cytoplasm conductivity by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 1595–1603 (2015).

Pierro, V., De Vita, A., Croce, R. P. & Pinto, I. M. Membrane heating in living tissues exposed to nonthermal pulsed EM fields. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 42, 2236–2244 (2014).

Joshi, R. P. & Schoenbach, K. H. Electroporation dynamics in biological cells subjected to ultrafast electrical pulses: a numerical simulation study. Phys. Rev. E 62, 1025–1033 (2000).

Pucihar, G., Kotnik, T., Kandušer, M. & Miklavčič, D. The influence of medium conductivity on electropermeabilization and survival of cells in vitro. Bioelectrochemistry 54, 107–115 (2001).

Rosenbluth, M. J., Lam, W. A. & Fletcher, D. A. Force microscopy of nonadherent cells: a comparison of leukemia cell deformability. Biophys. J. 90, 2994–3003 (2006).

National Bureau of Standards. Circular of the Bureau of Standards No. 31 3rd Edition: Copper Wire Tables (Government Printing Office, 1914).

Neal, R. et al. Treatment of breast cancer through the application of irreversible electroporation using a novel minimally invasive single needle electrode. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 295–301 (2010).

Miklavčič, D., Novickij, V., Kranj, M., Polajzer, T., Meglic, S. H., Batista Napotnik,T., Romih, R. & Lisjak, D. Bioelectrochemistry 132, 107440 (2019).

Ghorbel, A., André, F. M., Mir, L. M. & García-Sánchez, T. Electrophoresis-assisted accumulation of conductive nanoparticles for the enhancement of cell electropermeabilization. Bioelectrochemistry 137, 107642 (2021).

Wang, M., Orwar, O., Olofsson, J. & Weber, S. G. Single-cell electroporation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 397, 3235–3248 (2010).

Teissié, J. & Rols, M. P. An experimental evaluation of the critical potential difference inducing cell membrane electropermeabilization. Biophys. J. 65, 409–413 (1993).

Rols, M. P. Electropermeabilization, a physical method for the delivery of therapeutic molecules into cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1758, 423–428 (2006).

Pauly, H. & Schwan, H. P. Über die impedanz einer suspension Von Kugelförmigen Teilchen Mit Einer Schale. Z. für Nat. B 14, 125–131 (1959).

Kotnik, T., Miklavčič, D. & Slivnik, T. Time course of transmembrane voltage induced by time-varying electric fields—a method for theoretical analysis and its application. Bioelectrochem. Bioenergy 45, 3–16 (1998).

Kotnik, T., Bobanovic´, F. & Miklavčič, D. Sensitivity of transmembrane voltage induced by applied electric fields—a theoretical analysis. Bioelectrochem. Bioenergy 43, 285–291 (1997).

Timoshkin, I. V., MacGregor, S. J., Fouracre, R. A., Crichton, B. H. & Anderson, J. G. Transient electrical field across cellular membranes: pulsed electric field treatment of microbial cells. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 39, 596–603 (2006).

Novickij, V., Rembiałkowska, N., Szlasa, W. & Kulbacka, J. Does the shape of the electric pulse matter in electroporation? Front. Oncol. 12, 958128 (2022).

Asadipour, K., Zhou, C., Yi, V., Beebe, S. J. & Xiao, S. Ultra-low intensity post-pulse affects cellular responses caused by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. Bioengineering 19, 1069 (2023).

Guo, F., Qian, K., Li, X. & Deng, H. Simulation study of cell transmembrane potential and electroporation induced by time-varying magnetic fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 81, 103117 (2022).

Vasilkoski, Z., Esser, A. T., Gowrishankar, T. R. & Weaver, J. C. Membrane electroporation: the absolute rate equation and nanosecond time scale pore creation. Phys. Rev. E 74, 021904 (2006).

Vernier, P. T., Sun, Y. & Gundersen, M. A. Nanoelectropulse-driven membrane perturbation and small molecule permeabilization. BMC Cell Biol. 7, 37 (2006).

Vernier, P. T. et al. Calcium bursts induced by nanosecond electric pulses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 310, 286–295 (2003).

Craviso, G. L., Choe, S., Chatterjee, P., Chatterjee, I. & Vernier, P. T. Nanosecond electric pulses: a novel stimulus for triggering Ca2+ influx into chromaffin cells via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 30, 1259–1265 (2010).

Kiełbik, A. et al. Effects of high-frequency nanosecond pulses on prostate cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 15835 (2021).

Pakhomov, A. G. et al. Excitation and electroporation by MHz bursts of nanosecond stimuli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 518, 759–764 (2019).

Heller, R., Cruz, Y., Heller, L. C., Gilbert, R. A. & Jaroszeski, M. J. Electrically mediated delivery of plasmid DNA to the skin, using a multielectrode array. Hum. Gene Ther. 21, 357–362 (2010).

Gilbert, R. A., Jaroszeski, M. J. & Heller, R. Novel electrode designs for electrochemotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1334, 9–14 (1997).

Niculescu, A. G. & Grumezescu, A. M. Novel tumor-targeting nanoparticles for cancer treatment-A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5253 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Support from the U.S. Office of Naval Research under grant N00014-21-2055 is gratefully acknowledged. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein. Also, one of us (RPJ) acknowledges useful discussion with T. Batista Napotnik (University of Ljubljana).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: R. P. Joshi, W. Milestone, C. Baker, M. Baker, A. L. Garner; data collection: C. Baker, A. Willis; analysis and interpretation of results: R. P. Joshi, W. Milestone, C. Baker, A. Willis, M. Baker, A. L. Garner; draft manuscript preparation: R. P. Joshi, C. Baker, A. Willis, M. Baker, A. L. Garner. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, C., Willis, A., Milestone, W. et al. Numerical assessments of geometry, proximity and multi-electrode effects on electroporation in mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum to nanosecond electric pulses. Sci Rep 14, 23854 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74659-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74659-z