Abstract

In recent years, with the application of Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud technology in smart industrialization, Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has become an emerging hot topic. The increasing amount of data and device numbers in IIoT poses significant challenges to its security issues, making anomaly detection particularly important. Existing methods for anomaly detection in the IIoT often fall short when dealing with data imbalance, and the huge amount of IIoT data makes feature selection challenging and computationally intensive. In this paper, we propose an optimal deep learning model for anomaly detection in IIoT. Firstly, by setting different thresholds of eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for feature selection, features with importance above the given threshold are retained, while those below are ignored. Different thresholds yield different numbers of features. This approach not only secures effective features but also reduces the feature dimensionality, thereby decreasing the consumption of computational resources. Secondly, an optimized loss function is designed to study its impact on model performance in terms of handling imbalanced data, highly similar categories, and model training. We select the optimal threshold and loss function, which are part of our optimal model, by comparing metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, False Alarm Rate (FAR), Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), and Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve (AUC-PR) values. Finally, combining the optimal threshold and loss function, we propose a model named MIX_LSTM for anomaly detection in IIoT. Experiments are conducted using the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD datasets. The proposed MIX_LSTM model can achieve 0.084 FAR, 0.984 AUC-ROC, and 0.988 AUC-PR values in the binary anomaly detection experiment on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. In the NSL-KDD dataset, it can achieve 0.028 FAR, 0.967 AUC-ROC, and 0.962 AUC-PR values. By comparing the evaluation indicators, the model shows good performance in detecting abnormal attacks in the Industrial Internet of Things compared with traditional deep learning models, machine learning models and existing technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), an extension of Internet of Things (IoT) technology, has permeated various industries such as healthcare, autonomous driving, and home appliances, revolutionizing our lifestyle and industrial structure1. IIoT comprises not just connected devices and sensors but also builds a multidimensional complex system covering the physical layer, transport layer, and application layer, achieving seamless integration of intelligent computing, physical processing, and network communication. With ongoing technological advancements, the application of IIoT is expanding, being utilized for special purposes like real-time perception, dynamic control, and information services2. The core of IIoT lies in connecting everything via the internet, exchanging messages and signals through various protocols and networks. Common communication protocols, such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Modbus Transmission Control Protocol (Modbus TCP), and Long Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN), support communication and data transmission between devices3,4. However, the increase in communication devices and frequency has led to the generation of large and complex data in IIoT, such as videos, commands, images, etc. Moreover, with the diversity of communication protocols and applications, the big data generated faces threats of network and physical attacks from different level systems. Securing the data in IIoT networks has become one of our unavoidable challenges. To mitigate losses from malicious attacks in IIoT and enhance the performance of anomaly detection in processing IIoT data is an urgent issue to address.

A key problem in anomaly detection is the rarity of anomaly attacks, leading to imbalanced class distribution and a significant disparity between positive and negative samples. Traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques depend on large labeled databases for training anomaly detection models, making it challenging to enhance detection performance due to the aforementioned issues5. Another critical issue is the high dimensionality of IIoT data, making it a daunting task to extract reliable and representative features from vast, complex high-dimensional data for anomaly detection. Traditional feature extraction methods, like Principal Component Analysis (PCA)6, might yield poorer detection results when extracting representative features from nonlinear and imbalanced datasets. Apart from traditional methods, new approaches have been proposed by researchers and have made further breakthroughs in the field of anomaly detection. Researchers have made initial progress by constructing different autoencoders to re-encode high-dimensional features into lower dimensions7. Autoencoder (AE) technology8, widely researched for its primary purpose of reconstructing original input data, has achieved relatively good results in reducing dimensions and preserving features of the original data. However, AE cannot guarantee the complete retention of all most representative features during feature reduction, as they might overlook the potential attributes of features when processing imbalanced data, leading to the loss of some critical features.

While these technologies have improved the accuracy of anomaly detection to some extent, the performance of the False Alarm Rate (FAR) remains suboptimal, especially when dealing with data characterized by imbalanced classes and high feature dimensions. Therefore, proposing an optimal strategy to address the limitations of existing technologies is necessary. This involves developing methods to tackle the issue of class imbalance and optimizing the feature extraction process to achieve higher-performance anomaly detection.

To address the various challenges of anomaly detection in IIoT networks, we conducted in-depth exploration in feature extraction, loss function optimization, and model construction. Our research makes the following contributions:

-

1.

Proposing the use of the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model9 for feature extraction in complex IIoT data, obtaining importance scores for each feature. Different numbers of features are obtained by setting various feature importance thresholds, with the best feature set evaluated using multiple metrics.

-

2.

Introducing an optimized loss function to address the class imbalance in IIoT data. This loss function enhances anomaly detection performance by setting weights to balance the importance between classes.

-

3.

Designing the MIX_LSTM model, based on the traditional deep learning long short-term memory (LSTM) model, aiming to achieve superior anomaly detection performance.

Related work

In recent years, researchers have made significant efforts to solve the problem of anomaly detection in networks, conducting extensive studies in wireless networks10,11, IoT12, cloud-edge services13,14, and blockchain networks15,16. However, traditional methods have shown limitations in effectively detecting anomalies in the IIoT, thus underscoring the critical need for designing robust anomaly detection models tailored to current IIoT applications. Initially, some researchers proposed using various machine learning techniques to address these challenges. For instance, Alrashdi et al.17 introduced an Anomaly Detection- Internet of Things (AD-IoT) system to address threats in smart city IoT networks, a model based on random forest machine learning methods. This model achieved a precision of 0.79 on the attack category in the UNSW-NB15 dataset, indicating room for improvement in anomaly detection.

However, machine learning struggles with automatic hyperparameter tuning and effectively capturing complex relationships in high-dimensional IIoT data. To overcome these limitations, some researchers have shifted towards deep learning, achieving satisfactory results. Abusitta et al.12 proposed an anomaly detection method based on autoencoders, utilizing denoising autoencoders for important feature representation, combined with Support Vector Machine (SVM) and binary logistic regression classifiers. This method, integrating deep and machine learning, achieved an average accuracy of 94.6% on the Demand Side Management System Operator Security (DS2OS) traffic traces dataset, showing good performance but not utilizing representative datasets from IIoT. Li et al.18 proposed a decomposition-aggregation architecture by analyzing energy consumption of system subcomponents like CPU, network, and disk, and used a dual deep learning (DL) model, demonstrating strong performance in hardware simulations.

Compared to traditional deep learning models, more researchers are opting for deep learning variants to solve problems, achieving commendable results. Altunay et al.1 proposed three distinct models for detecting intrusions in IIoT networks. They utilized convolutional neural networks (CNN), LSTM, and a combined CNN + LSTM deep learning architecture generated from these networks. The performance of their models was evaluated using the UNSW-NB15 and X-IIoTID datasets. Their model achieved 93.21% binary classification accuracy on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, comparable to our model, but did not provide comprehensive performance metrics such as test set FAR, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), and Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve (AUC-PR). Zhou et al.19 and colleagues addressed the challenges of data dimension reduction and feature extraction in IIoT by introducing a Variational Long Short-Term Memory (VLSTM) learning model for smart anomaly detection based on reconstructed feature representation. This model first learned low-dimensional feature representations from high-dimensional data through encoding and decoding, defined three quantified loss functions, and finally trained the model using LSTM. They evaluated their proposed model framework using the UNSW-NB15 dataset, achieving a FAR of 0.117, while our FAR reached 0.084.

In the field of intrusion detection research in the industrial Internet of Things, current technologies mostly use PCA or deep learning technology to perform dimensionality reduction experiments, but there are few literatures analyzing the specific impact of dimensionality reduction data on model performance. Therefore, this study aims to make a basic exploration of dimensionality reduction effects by using the XGBoost machine learning method. At the same time, in order to deal with the problem of data imbalance and improve the clarity of the decision boundary of the model, this study also attempts to improve the detection accuracy by optimizing the weight loss function.

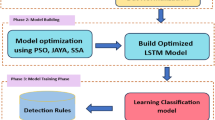

Methods

In this section, we delve into the detailed steps of the proposed optimal anomaly detection model. Initially, data preprocessing is conducted on two public datasets, UNSW_NB15 and NSL-KDD. During the preprocessing process, duplicate data of both features and labels are deleted, and data rows with empty label columns are deleted. Empty values in character and numeric features are filled with ‘---’ and 0, and character features are one-hot encoded20. Feature selection is then performed on the encoded data by adjusting the XGBoost threshold, followed by inputting this data into our designed MIX_LSTM model for training. Visualization of the dataset and the distribution of positive and negative samples during training is achieved using t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), aiding researchers in better observing and understanding the data21. Concurrently, the trend changes in model training accuracy and loss are presented, along with the confusion matrix, and the plotting of Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision–Recall (PR) curves. This approach helps to more intuitively display the performance advantages of the proposed method. Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed approach.

Feature extraction based on XGBoost

XGBoost is an efficient, flexible, and lightweight algorithm widely applied in machine learning, especially in fields like data mining and recommendation systems. Its fundamental concept involves the second-order Taylor expansion of the target function, utilizing second-order derivative information of the function to train tree models22. Moreover, it incorporates the complexity of tree models as a regularization term in the optimization objective, enhancing the generalization ability of the learned model. Hence, it is also known as gradient boosting decision trees. Let \(\:\zeta\:\) be the target function, \(\:{f}_{t}\) the feature parameters of the \(\:t\) tree, and \(\:\varOmega\:\left({f}_{t}\right)\) the model’s complexity. The second-order Taylor series of the target function \(\:\zeta\:\) at the \(\:t\) iteration is given by:

where \(\:{g}_{i}\) and \(\:{h}_{i}\) denote first and second-order gradients, respectively.

Similar to information gain and Gini index in decision trees, gain is used during model training to determine the best splitting node:

where \(\:{I}_{L}\) and \(\:{I}_{R}\) represent the samples in the left and right nodes after splitting, and \(\:I=\:{I}_{L}{\cup\:I}_{R}\); \(\:{\left({\sum}_{i\in\:{I}_{L}}{g}_{i}\right)}^{2}/\left({\sum}_{i\in\:{I}_{L}}{h}_{i}+\:\lambda\:\right)\) and \(\:{\left({\sum}_{i\in\:{I}_{R}}{g}_{i}\right)}^{2}/\left({\sum}_{i\in\:{I}_{R}}{h}_{i}+\:\lambda\:\right)\) represent the information scores of the left subtree and right subtree respectively; \(\:{\left({\sum}_{i\in\:I}{g}_{i}\right)}^{2}/\left({\sum}_{i\in\:I}{h}_{i}+\:\lambda\:\right)\) is the current indivisible information score; \(\:\lambda\:\) and \(\:\gamma\:\) are penalty parameters. Each tree split’s gain score is denoted by ‘gain’, and the importance score of features is calculated by the average gain across all features. The average gain is the total gain of all trees divided by the number of splits for each feature. In XGBoost, features with importance scores above a given threshold are retained, while those below are disregarded. By setting different thresholds, various numbers of features are obtained. The feature selection results for both datasets are shown in Table 1.

Loss function selection

To optimize model performance, we conducted a study on loss functions, comparing five common loss functions: Class Balanced Loss, Cross Entropy Loss, Focal Loss, Multi Dice Loss, and Multi Tversky Loss. Particular emphasis was placed on an in-depth study and optimization of Class Balanced Loss, which yielded the best results in subsequent experiments.

Class Balanced Loss23 is typically used to address the issue of class imbalance by re-weighting training samples, assigning higher weights to less frequent classes to balance the importance of each class. The aim of this loss function is to improve the prediction accuracy for classes with fewer samples, thereby enhancing the overall performance of the model. Our comprehensive study of this loss function began with the calculation of class frequency, given by:

where \(\:class\_count\left[i\right]\) represents the number of samples in class \(\:i\) within the target, and \(\:len\left(target\right)\) is the total number of samples in the target. This is followed by the calculation of the effective number:

where \(\:\beta\:\) is a hyper parameter used to adjust the distribution of weights. Here is the calculation of category weights, the weight applied to each category:

In the formula below, we adjusted the weights for all classes except the 0th class. By redistributing weights, the model’s classification performance on imbalanced class samples can be further improved.

The calculation formula for the optimized Weight Class Balanced Loss is as follows:

where \(\:y\) represents the true class labels of each sample, and \(\:output\left[i\right]\) is the model’s prediction output for each class.

Cross Entropy Loss, a common loss function for classification problems, measures the discrepancy between two probability distributions, that is, the difference between the probability distribution output by the model and the distribution of the actual labels. For binary classification and multi-classification problems, its formula is defined as follows:

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) are the true labels, \(\:{p}_{i}\) are the predicted probabilities, and \(\:C\) is the number of classes.

Focal Loss, proposed by Lin et al.24 in 2017, is tailored for class imbalance and difficult sample learning, particularly in tasks like object detection and image segmentation. Its formula is:

where \(\:{\alpha}_{t}\) is the class weight, \(\:{p}_{t}\) is the predicted probability, and \(\:{\upgamma\:}\) is an adjustable factor controlling the handling of easy and difficult samples.

Multi Dice Loss, used to measure the overlap between predictions and true labels, has the following loss calculation formula:

where \(\:p\) represents model predictions, \(\:t\) represents true labels. The \(\:intersection\) represents the part shared by the model prediction and the true label, while the \(\:union\) represents the sum of the two. \(\:\varepsilon\:\) is a small constant to prevent division by zero.

Multi Tversky Loss, a variant of Dice Loss, introduces two parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) to balance the weights of True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). Its formula is:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) adjust the importance of different classes, and \(\:\varepsilon\:\) is a small constant to avoid division by zero.

In our experiments, we compared the performances of these six loss functions on the same network structure and datasets, aiming to identify the optimal loss function for our model.

MIX_LSTM model

In this paper, we designed the MIX_LSTM model based on LSTM to detect anomalies in IIoT. The model utilizes a variant of LSTM, namely Bidirectional LSTM, which, unlike traditional LSTM, can consider both past and future information. Forward LSTM captures past information while backward LSTM captures future information, providing a more comprehensive and rich sequence representation.

Figure 2 shows the model structure. From left to right, the first part is the data input, which is the data after XGBoost feature selection. Next is the multi-layer Bidirectional LSTM module in the middle, which shows the structure of one, two and three layers of Bidirectional LSTM respectively. By stacking multiple Bidirectional LSTM layers layer by layer, the network can gradually learn to extract higher-order and more abstract features, thereby more comprehensively expressing the information of the input data. After splicing the outputs of all Bidirectional LSTM modules together, the final classification processing is performed through the fully connected layer on the right. The fully connected layer is responsible for mapping deep features to predetermined output categories to achieve accurate data classification and analysis.

LSTM is a specialized form of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), first introduced in 1997, effectively addressing the problem of vanishing gradients in model training25. LSTM typically consists of a candidate cell state \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{C}}_{t}\), cell state \(\:{C}_{t}\), hidden state \(\:{h}_{t}\), and three gates (input, output, and forget). Here, \(\:{h}_{t}\) is the network’s output, while the size of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{C}}_{t}\) is determined by the user. The gates in LSTM manage the writing, reading, and resetting of sequential data26. Notably, each gate’s final output undergoes processing through a sigmoid function, constraining the values between 0 and 12. The details of these units are as described in formulas (12) and (13).

where \(\:{\omega}_{xhc}\) and \(\:{\omega}_{hhc}\) are weight matrices, and \(\:{b}_{c}\) is the bias.

\(\:{C}_{t}\) represents the current time step’s cell state; \(\:{F}_{t}\) is the output of the forget gate, controlling the extent to which information from the previous time step is forgotten; \(\:{I}_{t}\) is the output of the input gate, controlling the degree of current time step information inclusion; and \(\:\odot\:\) denotes element-wise multiplication. This is key to mitigating the problem of gradient vanishing.

In LSTM, the forget gate plays a pivotal role. Controlled by the sigmoid activation function, the output of the forget gate is restricted between 0 and 1, determining which information from the previous time step’s memory state should be retained or forgotten. This mechanism allows the LSTM network to maintain and update important memories over a long period while selectively discarding irrelevant information, as illustrated in the following formula:

where \(\:{\chi}_{t}\) is the input at the current time step, \(\:{h}_{t-1}\) is the hidden state from the previous time step, \(\:{\omega}_{xf}\) and \(\:{\omega}_{hf}\) are weights, and \(\:{b}_{f}\) is the bias.

The input gate is the second gate in LSTM, playing a crucial role in controlling the degree to which the current time step’s input data updates \(\:{C}_{t}\). By regulating the influx of new data, the network can selectively update \(\:{C}_{t}\), better memorizing and ignoring certain parts of the input data. Its formula is as follows:

where \(\:{\omega}_{xi}\) and \(\:{\omega}_{hi}\) are the weight parameters of the input gate, and \(\:{b}_{i}\) is the bias.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed MIX_LSTM, various metrics like precision, F1 score, recall, FAR, AUC-ROC, AUC-PR, and accuracy are employed, as elaborated in27. These metrics depend on four terms: true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false negative (FN), and false positive (FP). These correspond to the count of actual attack vectors correctly classified as attacks, actual legitimate vectors correctly identified as legitimate, actual attack vectors misclassified as legitimate, and actual legitimate vectors misclassified as attacks, respectively. Notably, FAR represents the false alarm rate in detecting network traffic anomalies, a crucial aspect in anomaly detection. A higher FAR indicates poorer detection performance. AUC represents the classifier’s ability to distinguish between positive and negative cases, especially important for evaluating classifier performance in imbalanced samples. In this study, AUC and FAR are considered two crucial indicators for assessing anomaly detection performance in imbalanced IIoT datasets19.

In addition to these classic evaluation metrics, we have also introduced Negative Predictive Value (NPV) and Specificity, which indicate the model’s ability to correctly detect negative (normal) samples. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is a measure for evaluating the performance of binary classification models, particularly suitable for assessing models in imbalanced datasets.

Experiments and results

In this section, we first provide a detailed description of the data set preprocessing and experimental environment. Then we selected the optimal threshold and loss function as the components of the model according to the experimental results, and finally compared the proposed model MIX_LSTM with the traditional deep learning and machine learning models.

Data preprocessing

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed anomaly detection model, experiments were conducted using two publicly available datasets, detailed as follows.

The UNSW-NB15 dataset28 originated from raw network data packets generated by the IXIA PerfectStorm tool at the University of New South Wales Canberra Cyber Range Lab. This dataset aims to create a mix of realistic modern normal activities and synthetic contemporary attack behaviors. The attack types in this dataset include Fuzzers, Analysis, Backdoors, DoS (Denial of Service), Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode and Worms, which are like the attacks that may be encountered in the industrial IoT environment. For IIoT environments, this diverse set of attack scenarios provides an ideal benchmark for testing and evaluating the effectiveness of anomaly detection systems, especially in the face of various potential cybersecurity challenges. It contains 42 features and was initially divided into training and testing sets. In our experiments, we split the original training set of the UNSW-NB15 dataset into 70% for training and 30% for validation. The distribution of data volumes and the positive-negative sample distribution in the training, validation, and testing sets of the UNSW-NB15 dataset are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

The NSL-KDD dataset29 was created in 2009. The attack types include DOS, R2L (Remote to Local attack), U2R (User to Root attack) and Probe (Probing attack). It is widely used in network anomaly detection experiments. More and more researchers choose to experiment with the NSL-KDD dataset to compare various anomaly detection methods. In the IIoT environment, security threats to devices and networks are diverse, and NSL-KDD provides a multi-dimensional perspective to evaluate and improve anomaly detection systems, especially when dealing with unknown attacks or new attack patterns. The NSL-KDD dataset includes four pre-divided datasets: KDDTrain+, KDDTrain+ 20, KDDTest+, and KDDTest− 21. We selected KDDTrain+ and KDDTest+ as our training and testing sets, respectively. Similarly, 30% of the training set was divided as a validation set, with its data volume distribution and positive-negative sample distribution illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6.

As observed from the positive and negative sample distributions in Figs. 4 and 6, the UNSW-NB15 dataset is more imbalanced compared to the NSL-KDD dataset, indicating more significant challenges faced. For data preprocessing, we employed the classic one-hot encoding method30 to process non-numeric features in the datasets. This encoding approach aids in achieving better classification results.

Experiment set up

The experimental section was implemented using the Python programming language. The running and testing environment included an AMD Ryzen 9 5950 × 16-Core Processor, NVIDIA Corporation GA102GL [RTX A6000], with 32.0 GB of RAM, on the Linux kali 6.1.0-kali7-amd64 operating system, and PyTorch version 2.0.1 + gpu. The MIX_LSTM model was trained on the NSL-KDD dataset with 30 epochs, using a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 128, with the Adam optimizer. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the model was trained for 10 epochs, with the same learning rate of 0.001 and batch size of 128, also utilizing the Adam optimizer.

To evaluate the performance of MIX_LSTM, it was compared with state-of-the-art references19. Furthermore, to assess MIX_LSTM’s performance more thoroughly, it was compared with traditional machine learning models like MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) and conventional deep learning models like CNN and LSTM. Additionally, it was compared with hybrid deep learning models such as CNN_LSTM and MIX_CNN_LSTM. The parameters of the MIX_LSTM model is shown in Table 2, including parameters for the LSTM and fully connected layers. It should be noted that there are 4 Linear layers in the given FC layers. The first three Linear layers gradually reduce the dimension of the output features. This is to allow the model to gradually extract and compress more critical feature information, while avoiding jumping directly from the high-dimensional space to the final classification output. Such a gradual reduction can help the model learn more effective feature representations and perform smoother feature conversions. Each Linear layer is followed by BatchNorm, ReLU, and Dropout. This configuration helps to enhance the stability and nonlinear processing capabilities of the model during training, prevent overfitting, and enhance the model’s generalization ability on new data. Such a multi-layer design not only improves the learning ability of the model, but also enhances its generalization ability, making the model more robust when processing unseen data.

Selection of number of features based on XGBoost technology

To obtain the optimal model, on the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD datasets, the XGBoost technique was utilized. We observed the experimental results under different thresholds by adjusting them. The specific threshold selection is shown in Table 1. Figures 7 and 8a and b illustrate the accuracy and loss curves under different thresholds on the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD training sets, while (c) and (d) show these curves on the validation sets.

To select the optimal threshold, we first considered the AUC-ROC and AUC-PR values. The ROC provides a comprehensive assessment of classification performance, while the PR curve focuses more on class recognition accuracy in imbalanced datasets. Therefore, we used ROC and PR as two crucial indicators for selecting the best threshold. The area under the curve (AUC) measures the performance of the ROC curve; a larger AUC value indicates better classifier performance. In the PR curve, the Average Precision (AP) represents the area under the curve, describing the relationship between precision and recall. The ROC and PR curves for various thresholds on the UNSW-NB15 test set are shown in Fig. 9a and b, with the highest AUC value being 0.985 and the highest AP value being 0.989, both corresponding to a threshold of 0.002 and a feature count of 31. For the NSL-KDD test set, as shown in Fig. 10a and b, the highest AUC value is 0.967, and the highest AP value is 0.963, both corresponding to a threshold of 0.003 and a feature count of 23.

To further determine the threshold selection, we comprehensively compared various evaluation metrics, such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, Specificity, F1 Score, NPV, AUC-ROC, MCC, AUC-PR, and FAR. Figure 11a and b display the performance at different thresholds for the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD test sets. In anomaly detection, the FAR value is of particular importance, with a smaller FAR indicating better performance. In the UNSW-NB15 test set, the minimum FAR value is 0.084, corresponding to a threshold of 0.002. Therefore, in the UNSW-NB15 dataset, our final chosen threshold is 0.002, corresponding to 31 features. In the NSL-KDD test set, the minimum FAR value is 0.028, corresponding to thresholds of 0.005 and 0. However, when the threshold is 0.005 and 0, the corresponding AUC values are 0.918 and 0.877, and AP values are 0.918 and 0.883, respectively. Due to the lower AUC and AP, and considering the model’s overall optimal performance, we selected the threshold with an FAR of 0.029, which is only 0.001 higher but has the highest AUC and PR values. Therefore, in the NSL-KDD dataset, our final chosen threshold is 0.003, corresponding to 23 features.

Selection of optimal loss function

For consistency with the purpose of feature extraction, we compared the following five loss functions: Class Balanced Loss, Cross Entropy Loss, Focal Loss, Multi Dice Loss, and Multi Tversky Loss, as well as our proposed optimized loss function, Weight Class Balanced Loss. The loss function that performs best overall will be selected as a component of the optimal model. This experiment was conducted under the premise of the determined optimal thresholds, with the UNSW-NB15 dataset having 31 features and the NSL-KDD dataset having 23 features. Figures 12 and 13a and b showcase the accuracy and loss curves under different loss functions for the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD training sets, while (c) and (d) display these curves on the validation sets.

Similarly, to choose the optimal loss function, we compared the AUC-ROC and AUC-PR values among various loss functions. For the UNSW-NB15 test set, the ROC and PR curves for different loss functions are shown in Fig. 14a and b. The highest AUC value was 0.985, and the highest AP value was 0.989, corresponding to the Weight Class Balanced Loss, Class Balanced Loss, Cross Entropy Loss, and Focal Loss. To select the best loss function, further experiments were needed. For the NSL-KDD test set, as depicted in Fig. 15a and b, the highest AUC value was 0.967 and the highest AP value was 0.963, both corresponding to the Weight Class Balanced Loss. Thus, this loss function was initially identified as the most optimal.

In the UNSW-NB15 test set, the Weight Class Balanced Loss, Class Balanced Loss, Cross Entropy Loss, and Focal Loss all shared the same AUC and AP values. To pick the most suitable loss function for anomaly detection, we focused on the size of the FAR value. Figure 16a displays the performance of different loss functions on the UNSW-NB15 test set. Among these, our proposed optimized loss function, Weight Class Balanced Loss, had the smallest FAR value of 0.084, significantly lower than the others. Therefore, this loss function was chosen as the optimal one, demonstrating its effectiveness in controlling the false alarm rate in anomaly detection tasks. Figure 16b shows the performance of different loss functions on the NSL-KDD test set. The lowest FAR value of 0.027 corresponded to the Multi Tversky Loss. However, its AUC and PR values were only 0.762 and 0.841, respectively. The Weight Class Balanced Loss had a slightly higher FAR of 0.029, but its AUC and PR values reached 0.967 and 0.963, significantly higher than those of the Multi Tversky Loss. Thus, from an overall performance perspective, the Weight Class Balanced Loss was the more appropriate choice as the optimal loss function.

The performance of MIX_LSTM model

After determining the threshold selection and loss function for each data set, we conduct experiments based on this to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed model. First, the performance of the proposed MIX_LSTM model was evaluated using confusion matrices. Figure 17a and b present the binary classification results of MIX_LSTM on the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD test sets. The numbers in the confusion matrix include the true positive rate and false negative rate for classifying malicious intrusions. The numbers on the diagonal represent the count of correctly classified samples, while those off the diagonal indicate misclassified samples. The analysis of the confusion matrices revealed that MIX_LSTM performed well on both datasets.

Figures 18 and 19 show the loss and accuracy curves of the MIX_LSTM model on the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD training and validation sets. Observations indicate that both the minimum loss value and maximum accuracy value occurred in the final stages of training iterations, suggesting that the model had reached a state of convergence.

Figures 20 and 21 illustrate the distribution trends of positive and negative samples in different layers of the MIX_LSTM neural network for the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD test sets. From parts (a) of Figs. 20 and 21, it is evident that at the initial entry into the first layer of LSTM, positive and negative samples are mixed, indicating the model’s inability to effectively distinguish between classes at this stage. However, parts (b) of Figs. 20 and 21, showing the post-fully connected layer distribution of samples, reveal a clear spatial distinction, indicating good classification effectiveness. The t-SNE visualizations help us understand the overall distribution and patterns of the data more intuitively, thereby enhancing our comprehension of the model’s capability to differentiate classes.

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed MIX_LSTM model, we designed four deep learning models and one machine learning model, MLP, for comparative experiments. These deep learning models include traditional ones like CNN and LSTM, as well as hybrid models such as CNN_LSTM and MIX_CNN_LSTM. Figures 22 and 23a and b display the accuracy and loss curves of different models on the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD training sets, while (c) and (d) show these curves on the validation sets. Figures 22 and 23 support the superior performance of MIX_LSTM in anomaly detection compared to other models.

Figures 24 and 25 present the ROC and PR curves for the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD test sets, clearly demonstrating the performance advantage of the MIX_LSTM model. From Fig. 24a and b, the model’s AUC value is observed to be 0.985 and AP value 0.989, slightly higher than those of LSTM-related deep learning models, significantly higher than traditional machine learning models, and far exceeding the CNN model. This indicates that models based on LSTM exhibit superior performance in handling anomaly detection problems. Figure 25a and b show that the MIX_LSTM model maintains consistent performance across different datasets, while other models that previously performed similarly to MIX_LSTM show variations on the NSL-KDD set. For example, MIX_CNN_LSTM achieved AUC and AP values of 0.983 and 0.987, respectively, on the UNSW-NB15 test set, but only 0.931 and 0.929 on the NSL-KDD test set. This suggests that MIX_LSTM’s robustness is superior to other models.

To further highlight the performance of MIX_LSTM, we compared it with advanced techniques. In related work, VLSTM model proposed by Zhou et al.19, a hybrid CNN + LSTM model by Altunay et al.1, and the AD-IoT method by Alrashdi et al.17 was contrasted, as shown in Fig. 26. MIX_LSTM demonstrated high performance on the UNSW-NB15 test set with a precision of 0.932, recall of 0.942, F1 score of 0.937, FAR of 0.084, AUC-ROC of 0.985, and MCC of 0.858. Graphical analysis reveals that MIX_LSTM outperforms other models and methods in terms of precision, F1 score, FAR, and AUC-ROC. However, the recall of MIX_LSTM is slightly lower compared to other models such as MIX_CNN_LSTM, CNN, and VLSTM, indicating a weaker performance in correctly identifying positive samples. Notably, MIX_LSTM achieves the lowest FAR and the highest MCC, suggesting its superior performance in reducing false positives and overall classification effectiveness.

The challenges faced by MIX_LSTM on the NSL-KDD dataset is somewhat greater compared to the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Figure 27 shows the anomaly detection performance of different models on the NSL-KDD test set. AUC-ROC and AUC-PR reflect the overall performance of the model, with our proposed model achieving 0.967 and 0.963 on these two metrics, respectively. Additionally, its accuracy, F1 score, MCC, and FAR values are 0.823, 0.821, 0.685, and 0.029, leading ahead of deep learning and machine learning methods. Its precision is 0.970, slightly lower than CNN’s 1, but CNN performs poorly on other metrics, indicating inferior overall performance. Besides comparisons with deep learning and machine learning, we also contrasted with existing technologies. Li et al.31 proposed a multi-CNN fusion method for addressing malicious intrusions in IIoT, validated as a high-precision, low-complexity classification method on the NSL-KDD dataset. Vinayakumar et al.27 proposed a highly scalable and hybrid deep neural networks (DNN) framework, known as scale-hybrid-IDS-AlertNet, focusing on the impact of the number of layers in DNN models on classification effectiveness. We chose their best-performing result in terms of layer number for our comparative experiment. Metrics marked as NULL in Fig. 27 indicate values not provided in the respective studies. According to the data analysis, the proposed model slightly lags behind the Multi-CNN model in accuracy and F1 score. However, the proposed model’s FAR of 0.029 is significantly lower than Multi-CNN’s 0.135, crucial in anomaly detection. Simultaneously, our model’s precision outperforms the Multi-CNN model. Compared to the DNN model, our model excels in all metrics, demonstrating better performance.

Scalability analysis of MIX_LSTM model

The model has a training time of 748.371 s, a model size of 8.221 MB, a CPU memory usage of 1.839GB, and a test time of 1.711 s on the NSL-KDD dataset. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the training time is 443.204 s, the model size is 10.721 MB, the CPU memory usage is 1.861GB, and the test time is 6.907 s. These parameters reflect the resource requirements and efficiency of the model when processing different datasets.

Further discussing the computational overhead or resource requirements of the intrusion detection system, longer training time and larger model size may lead to slow system response, especially in real-time monitoring environments that require fast response. The longer training time (748.371 s) and shorter test time (1.711 s) of MIX_LSTM on the NSL-KDD dataset may indicate that although the model training process is complex and time-consuming, the model can respond quickly in actual use and is suitable for scenarios that require fast decision-making. MIX_LSTM showed relatively short training time (443.204 s) and long test time (6.907 s) on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. This may indicate that the model is efficient to train, but may take more time to process data in actual detection, which may affect its application in high-speed network environments.

In addition, model size and memory usage will also affect the operating efficiency of the system, especially in resource-limited settings. The MIX_LSTM model size and memory usage are relatively moderate on both datasets, indicating that these models may run well in resource-limited environments, but the slightly larger model (10.721 MB) on the UNSW-NB15 dataset may lead to slightly higher resource consumption.

Conclusion

In this paper, we investigated methods to explore the optimal deep learning model to address issues of data imbalance and high feature dimensionality in IIoT data. The model was validated using IIoT related datasets for anomaly detection within IIoT, achieving satisfactory detection performance.

We introduced the machine learning method XGBoost for feature selection by setting different thresholds. Features with importance scores higher than the given threshold were retained, while those below were disregarded, allowing for varying numbers of features to be obtained. However, when using XGBoost for feature selection, the feature subset space that needs to be traversed is too large, which will take up more computing resources. Additionally, we compared five different loss functions and our proposed optimized loss function to assess their impact on model performance. These loss functions were designed to address issues such as imbalanced data, highly similar categories, and model training. By comparing metrics such as FAR, AUC-ROC, and AUC-PR values, we selected the most optimal thresholds and loss functions as integral parts of the optimal model. Ultimately, we proposed a model named MIX_LSTM, which was compared with deep learning, machine learning, and existing advanced technologies using the UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD datasets. The experimental results indicated that the proposed optimal model MIX_LSTM effectively resolves the problems of data imbalance and high feature dimensionality in IIoT data, achieving superior anomaly detection performance.

In future research, we realize that data imbalance and high dimensionality of features are still a challenge in IIoT anomaly detection tasks. At the same time, there is still room for improvement in the performance of the framework proposed in this study. We plan to test the model on different datasets to verify its generalization ability and ability to adapt to different environments. At the same time, we will also explore other feature selection methods, such as information gain-based or game theory-based selection techniques, to reduce the complexity of model training and improve the accuracy of prediction. We expect that the developed models and methods can be widely used in various fields, thereby achieving broader social and economic benefits.

Data availability

The UNSW-NB15 dataset analyzed during the current study is available in the following link: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/unsw-nb15-dataset. The NSL-KDD dataset analyzed during the current study is available in the following link: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html.

References

Altunay, H. C. & Albayrak, Z. A hybrid CNN+LSTM-based intrusion detection system for industrial IoT networks. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J.38, 101322 (2023).

Nizam, H., Zafar, S., Lv, Z., Wang, F. & Hu, X. Real-time deep anomaly detection framework for multivariate time-series data in industrial IoT. IEEE Sens. J.22, 22836–22849 (2022).

Özarpa, C., Aydin, M. A. & Avci, I. International security standards for critical oil, gas, and electricity infrastructures in smart cities: A survey study. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 4 Vol. 183 (eds Ben Ahmed, M. et al.) 1167–1179 (Springer, 2021).

Munirathinam, S. Industry 4.0: Industrial Internet of Things (IIOT). In Advances in Computers vol. 117 129–164 (Elsevier, 2020).

Wang, T., Xu, J., Zhang, W., Gu, Z. & Zhong, H. Self-adaptive cloud monitoring with online anomaly detection. Future Gener. Comput. Syst.80, 89–101 (2018).

Wold, S., Esbensen, K. & Geladi, P. Principal Component Analysis.

Yin, C., Zhang, S., Wang, J. & Xiong, N. N. Anomaly detection based on convolutional recurrent autoencoder for IoT time series. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst.52, 112–122 (2022).

Kingma, D. Stochastic Gradient VB and the Variational Auto-Encoder.

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (ACM, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

Rahman, A. et al. Network anomaly detection in 5G networks. Math. Model. Eng. Probl.9, 397–404 (2022).

Abd Algani, Y. M. et al. Analyze the anomalous behavior of wireless networking using the big data analytics. Meas. Sens.23, 100407 (2022).

Abusitta, A. et al. Deep learning-enabled anomaly detection for IoT systems. Internet Things21, 100656 (2023).

Sinha, S., Tomar, D. S. & Pateriya, R. K. Anomaly detection for edge computing: A systematic literature review. 040015 (Raipur (CG), India, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0133550.

Bacchiani, L. et al. Low-latency anomaly detection on the edge-cloud continuum for industry 4.0 applications: The SEAWALL case study. IEEE Internet Things Mag.5, 32–37 (2022).

Martin, K., Rahouti, M., Ayyash, M. & Alsmadi, I. Anomaly detection in blockchain using network representation and machine learning. Secur. Priv.5, e192 (2022).

Ul Hassan, M., Rehmani, M. H. & Chen, J. Anomaly detection in blockchain networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor.25, 289–318 (2023).

Alrashdi, I. et al. AD-IoT: Anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart city using machine learning. In 2019 IEEE 9th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) 0305–0310 (IEEE, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCWC.2019.8666450.

Li, F., Shi, Y., Shinde, A., Ye, J. & Song, W. Enhanced cyber-physical security in Internet of Things through energy auditing. IEEE Internet Things J.6, 5224–5231 (2019).

Zhou, X., Hu, Y., Liang, W., Ma, J. & Jin, Q. Variational LSTM enhanced anomaly detection for industrial big data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform.17, 3469–3477 (2021).

Hussein, A. Y., Falcarin, P. & Sadiq, A. T. Enhancement performance of random forest algorithm via one hot encoding for IoT IDS. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. PEN9, 579 (2021).

Arora, S., Hu, W. & Kothari, P. K. An analysis of the t-SNE algorithm for data visualization. Preprint at arXiv:1803.01768 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. Improving protein-protein interactions prediction accuracy using XGBoost feature selection and stacked ensemble classifier. Comput. Biol. Med.123, 103899 (2020).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations.

Lin, T.-Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection.

Palangi, H., Ward, R. & Deng, L. Distributed compressive sensing: A deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Signal Process.64, 4504–4518 (2016).

Smagulova, K. & James, A. P. Overview of long short-term memory neural networks. In Deep Learning Classifiers with Memristive Networks Vol. 14 (ed. James, A. P.) 139–153 (Springer, 2020).

Vinayakumar, R. et al. Deep learning approach for intelligent intrusion detection system. IEEE Access7, 41525–41550 (2019).

Moustafa, N. & Slay, J. The evaluation of network anomaly detection systems: Statistical analysis of the UNSW-NB15 data set and the comparison with the KDD99 data set. Inf. Secur. J. Glob. Perspect.25, 18–31 (2016).

Tavallaee, M., Bagheri, E., Lu, W. & Ghorbani, A. A. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications 1–6 (IEEE, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/CISDA.2009.5356528.

Kumar, P., Gupta, G. P. & Tripathi, R. TP2SF: A trustworthy privacy-preserving secured framework for sustainable smart cities by leveraging blockchain and machine learning. J. Syst. Archit.115, 101954 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Robust detection for network intrusion of industrial IoT based on multi-CNN fusion. Measurement154, 107450 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.62262019), the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No.823RC488, No.623RC481, No.620RC603), the Haikou Science and Technology Plan Project of China (No.2022-016), Special Support Plan for High level Talents in Zhejiang Province (No.2021R52019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. and L.Z.W. designed the research, conceived the experiments and drafted the manuscript; H.J. and L.S.Z collected datasets and performed part of experiments; L.H.X. provided guidance of this research and edited the manuscript; All of the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Li, Z., Huang, J. et al. An effective method for anomaly detection in industrial Internet of Things using XGBoost and LSTM. Sci Rep 14, 23969 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74822-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74822-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing SDN security with deep learning and F-balanced cross-entropy for DDoS detection

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Hybxlstm: a hybrid xLSTM-XGBoost model for securing O-RAN against backdoor attacks

Computing (2025)

-

Addressing smart city security: machine and deep learning methodology combining feature selection and two-tier cooperative framework tuned by metaheuristics

Cluster Computing (2025)