Abstract

This study analysed the relationship between the structured and unstructured activities of preschoolers and their mental and physical health, and also investigated the predicted changes in mental and physical health by reallocating activity time. This cross-sectional study was carried out with 324 preschoolers. Video recording and SOPARC activity observation system was used for the division of structured and unstructured activities. An accelerometer sensor was used to measure activity intensity. The SDQ psychological questionnaire was adopted to collect data on internalizing difficulties, externalizing difficulties, total difficulties and pro-social behaviours. Physical indices including body shape (height, weight, BMI), and physical fitness (upper and lower limb strength, flexibility, agility, and balance) were collected using Chinese toddler physical fitness measurement tools. Component data and isotemporal reallocation analyses were conducted using R Studio (Version 4.2). A total of 308 preschoolers (160 boys; aged 4.50 ± 0.93 years) were included in the data analysis. The activities composition, adjusted for sex, area, mental level (for mental indicators), or age (for physical indicators), was significantly correlated with various measurement indicators (p < 0.05). Specifically, structured (β=-0.87, p < 0.05) and unstructured (β=-1.24, p < 0.05) moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) were significantly positive correlated with internalizing difficulties, while structured MVPA was significantly positively correlated with body shape (β = 2.17, p < 0.05). Replacing structured light physical activity (LPA) with 10 min of structured MVPA has a positive effect on internalizing difficulties (SMD=-1.28, 95%CI: -2.30 to -0.27) and body shape (SMD = 1.76, 95%CI: 0.37 to 3.15). When the total replacement time reaches 25 min, the benefits become even more pronounced. Structured and unstructured MVPA are both beneficial to preschoolers’ mental and physical health, with the incorporation of MVPA for over 25 min in structured activities and supplementary unstructured MVPA yielding even greater benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mental and physical health of preschoolers constitutes a major public health issue confronting the world1. Mental health problems affect 10–20% of children and adolescents globally2, and approximately 20% of preschoolers in European countries are overweight or obese, while the figure reaches as high as 30% in North America3. Furthermore, there is mounting evidence that preschoolers’ mental or physical issues directly impact their healthy lives in adulthood4,5.

Although previous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have reported that increasing physical activity (PA) is a beneficial means to improve the mental and physical health of preschoolers6,7,8, further isotemporal reallocation studies have found that within a 24-hour period, different activity behaviours (light physical activity (LPA), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), sedentary behaviour (SB), sleep (SP)) exhibit varying health benefits (such as improved fitness9,10,11,12, executive functions13,14, fundamental movement skills15, fat percentage16, sleep quality17, mental problems18) when they substitute for each other. More specifically, increasing MVPA time and reducing SB time can significantly enhance the preschoolers’ physical fitness11 and mitigate mental problems18 of preschoolers. However, in reality, the effects of preschoolers’ PA in daily life cannot be solely categorized based on the intensity of the activity, as they vary across different scenarios.

Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO)19, the National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE)20, and the National Physical Activity Plan Alliance (NPAPA)21 classify PA into structured PA (including school physical education, school/club sports programs, and active-after-school care) and unstructured PA (such as active travel, active play, informal games, recess, lunch, etc.), based on activity scenarios or content. They emphasize the significance of both structured and unstructured activities for preschoolers in meeting their health requirements. Several controlled experiments and systematic reviews have found that structured PA can not only enhance fundamental motor skills22 and physical fitness23 in preschoolers, but also alleviate social and mental issues24. Furthermore, there is evidence that unstructured PA can effectively improve the mental health of preschoolers25. However, earlier randomized controlled trials found that there was a compensatory effect between daily structured and unstructured activities, and total physical activity did not increase in the absence of autonomous motivation26. Therefore, exploring the health benefits of different proportions or doses of structured and unstructured activities from a time dimension can provide more scientifically feasible solutions in practical teaching or guidance, which is of great value.

However, there is currently no research exploring the health benefits of structured and unstructured activities for preschoolers from a time dimension. Therefore, this study uses a compositional and isotemporal reallocation model to investigate the impact of different proportions or doses of structured and unstructured activities on the mental and physical health of preschoolers from a time dimension. It aims to enrich and improve the research system of structured and unstructured activities for children.

Methods

The sample size was estimated based on the variability of physical activity, with α = 0.05 (i.e., 95%CI), t = 1.96, r = 0.1 (error rate), S = 16.4 (population standard deviation), \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\)=32.7 (population mean), deff=2 (design effect), and a 50% loss rate reserved27. The calculation indicated that the sample size should be no less than 290 individuals, and 308 individuals were actually recruited.

Participants

In this study, a cluster-stratified sampling method was utilized to divide the sample into three tiers according to Jiangxi Province’s 2021 per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ranking of China28. One municipality was randomly selected from each stratum, totalling three municipalities (Yingtan, Pingxiang, and Ganzhou). Within each municipality, three kindergartens were chosen, amounting to a total of nine kindergartens. The participants were preschooler aged three to six years old, and a total of 358 preschoolers were recruited.

The inclusion criteria for this study were that the parents of the participating preschoolers must complete the SDQ psychological questionnaire, and the participating preschoolers must complete all physical activity measurements, physical health tests, and satisfy the requirement of at least one day of video recording. To avoid potential additional effects stemming from developmental delay, we excluded preschoolers who exhibited physical and cognitive dysfunction, with a Gesell Developmental Quotient (DQ) score of less than 75.

A total of 324 preschoolers met the inclusion criteria. After testing, one sample was missing from video observation, four samples were invalidated in the PA test, six samples were missing from the psychological questionnaire test, and five samples were missing from the physical fitness test. Finally, a total of 308 valid samples (160 boys; aged 4.50 ± 0.93 years) were obtained, representing a sample validity of 95.06%.

All parents gave written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (research clinical review [2020] No. (125)). During the research period, the COVID-19 epidemic was raging. The research followed the local prevention and control requirements and obtained the permission of the local education bureau and kindergarten. The government approval document is: Jiangxi Provincial Sports Bureau Document (Gan Ti Qun Zi [2021] No. 1). The test process is carried out strictly in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines/regulations.

Materials and methods

Structured-unstructured activity Behaviour Measurement

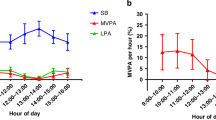

Physical activity level measurements

Preschoolers’ PA levels were measured using a triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph GT3X-BT, Pensacola, FL, USA) device. Participants wore them for five consecutive working days, 5 × 24 h in total. The instrument was initially set up and distributed to the children prior to testing. At the time of distribution, a parent-teacher conference was held to explain in detail the content of the test and the precautions to be taken, and to inform the preschooler that the device should be worn continuously (except for bathing and swimming time) until the end of the test. The device was worn on the right side of the preschooler’s iliac crest through an elasticated belt. Staff members checked the device wearing in the kindergarten every day and kept a record (Fig. 1). The device was collected by the researchers one day after the test. The data were downloaded and analysed using ActiLife (Version 6.13.4) with a sampling interval of 15 s29. Unworn time was calculated using the Choi algorithm, and the effective wearing time for the day was limited to at least 480 min30. If unworn time was due to sleep, time was recategorized as sleep. SB, LPA and MVPA were calculated concerning the Butte cut-off settings (SB: Counts ≤ 239, LPA: 240 ≤ Counts ≤ 2119, MVPA: Counts ≥ 2120)29.

Behavioural assessment of structured-unstructured activity behaviour

Information on structured and unstructured behavioural characteristics of preschoolers was collected with the help of video observations. Observation videos were recorded using a motion camera, DJI Osmo 4 K-X3/FC350H (produced by DJI, Shenzhen, China), for five working days. The video recording parameters are set to 1080p and 60hz31.

The observation in the kindergarten adopts the method of fixed-position installation of motion cameras, with one motion camera installed in each room of the indoor areas and two to three sets installed in each outdoor area, for a total of eight to 28 sets in each kindergarten. Indoor areas included classrooms, gymnasiums, art rooms, reading rooms, music and dance rooms, halls, etc., and the cameras were positioned at an angle between the ceiling and the wall, allowed for a complete view of the entire room (Fig. 2-left). The outdoor areas was installed at high points providing a full view of the outdoor area, such as the facade of the school building, a fence, a flagpole, etc. (Fig. 2-right).

Outside the kindergarten setting (such as at home), the motion camera was secured to the front of the participant’s preschooler’s chest using a sports harness. he wearing time begins when the preschoolers leave the kindergarten and continues until before bedtime each day, resuming the next morning when they wake up until they enter the kindergarten again. The total wearing time includes all the time outside the kindergarten for five working days. Prior to the start of the test, the research staff held a parents’ meeting with the assistance of the kindergarten teachers to explain in detail the content of the test and the precautions parents should take, informing them that the device should be worn at all times except for bathing and sleeping, and requested parents to help with putting on and removing the device during the test.

At the end of the test, two trained researchers assessed the preschooler’s structured and unstructured behaviours by playing back the video on a computer and utilizing the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC)32 as a structured-unstructured behavioural rating criterion. Any disagreement between the two researchers was then referred to the evaluation committee for further discussion and final determination. The evaluation process is for researchers to identify a labelled preschooler and follow his/her daily activities through videos. During the observation period, a table that can record continuous events is created according to the coding in SOPARC. The table includes the ID of the observed child, activity content, the start and end time of each activity, and whether the activity is structured or unstructured.

The results of the preschooler’s structured-unstructured behavioural trait ratings were imported into ActiLife (Version 6.13.4) in the form of time ranges for the measurement of structured and unstructured activity behaviour levels. There were 7 observations containing SP with 6 structured-unstructured activity behaviour indicators (including structured LPA, structured MVPA, structured SB, unstructured LPA, unstructured MVPA, unstructured SB).

Mental health measurement

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)33 was used to assess the mental health status of preschoolers. The questionnaire has 25 questions in total, and each selection is scored on a three-point scale (0 = Never, 1 = Sometimes, and 2 = Always). For example, question: your child can empathize with others. Options: never, sometimes, always.

Among the 25 questions, every 5 questions refer to a psychological issue, namely emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and pro-social behaviour. Among them, emotional symptoms and peer problems belong to SDQ-Internalizing Difficulties, while conduct problems and hyperactivity belong to SDQ-Externalizing Difficulties.

The scores of SDQ-Internalizing Difficulties and SDQ-Externalizing Difficulties are added up to obtain the SDQ-Total-Difficulties Score. When the SDQ-Total-Difficulties score ranges from 0 to 15, the psychological rating is normal; when the score is between 16 and 19, the psychological rating is borderline; and when the score falls within the range of 20 to 40, the psychological rating is abnormal.

The Chinese translated version of the SDQ scale has been used in the Chinese population, and the internal consistency of the SDQ scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.784) is good34. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this study is 0.741.

Physical health measurement

All the testing instruments were those of the “5th National Physical Fitness Monitoring of China” (produced by Jianmin, Beijing, China), and the testing standard is “China National Physical Fitness Measurement Standard (Revised in 2023)” (Early Childhood Section)35. The test items include: (1) body shape: height (cm), weight (kg), Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2); (2) physical fitness: grip strength (kg), standing long jump (cm), sitting forward bending (cm), two-legged continuous jump (s), 15-metre obstacle running (s), walking on the balance beam (s). The scores of all test indicators are based on a percentage system, in which the body shape score = height score × 0.2 + BMI score × 0.1, and the physical fitness score = grip strength × 0.1 + standing long jump × 0.1 + seating forward bending × 0.1 + two-legged continuous jump × 0.15 + 15-metre obstacle running × 0.1 + walking on the balance beam × 0.15.

Statistical analyses

Demographic information statistics

By using independent samples and ANOVA tests for demographic information, we aim to identify factors with significant differences. These significant factors will then be used as adjustment variables in the component analysis. The collected data are normally distributed, with the data format presented as Mean (M) ± Standard Deviation (SD). A P-value of less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) is considered statistically significant. The statistical software used for this analysis is SPSS Statistics 26.0 (produced by IBM, Chicago, USA).

Compositional data and regression modeling

Using R Studio (version 4.2), we conducted compositional data analysis utilizing the compositions package (version 2.0–8), rebcompositions package (version 2.4.1), zcompositions package (version 1.5.0–3), and lmtest package (version 0.9–40). All program codes are provided in the supplementary file. The compositional makeup (structured LPA, structured MVPA, structured SB, unstructured LPA, unstructured MVPA, unstructured SB, sleep) was described in terms of central tendency (the geometric mean). Linear adjustments were made to ensure that the total time for all components summed up to 24 h, or 1440 min9.

Dispersion analysis is employed to quantify the degree of variability or dispersion among the variables in the component data. This degree of dispersion is typically captured by a variance-covariance matrix, where the smaller the variances (diagonal elements) and covariances (off-diagonal elements) are, the less variability there is within and between the variables, respectively36. However, when discussing correlation specifically, closer covariance values to 0 indicate weaker correlations between variables, whereas larger absolute covariance values (in the context of standardizing for variance) would suggest stronger correlations. Note that the strength of correlation does not directly translate to the overall variability of the data, but rather to the degree of linear relationship between variables37.

A multiple linear regression model was employed to investigate the relationship between each component (explanatory variable) and each health indicator (dependent variable). Prior to inclusion in the regression model, each component was transformed using isometric logratio (ILR) to form a set of 6 ILR coordinates38. Additionally, covariates (variables found to be significant during demographic analysis) were included as adjustment variables in the calculations. Furthermore, to ensure the validity of the research hypotheses, the linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and outlier observations of the ILR multiple linear regression model were thoroughly examined. The significance of the each composition (i.e., the set of ILR coordinates) was examined with the “car::ANOVA()” function, which uses Wald chi- squared to calculate Type II tests, according to the principle of marginality, testing each covariate after all others39.

Isotemporal reallocation analysis

Using the aforementioned ILR multiple linear regression model, we aim to predict the differences in the outcome variables when a fixed duration (10 min) is reallocated between two activity behaviours, while the remaining activity components remain constant. This was achieved by creating a new series of activity compositions to simulate a 10-min reallocation between all pairs of activity behaviours, using the average composite of samples as the baseline or starting composite. The new compositions were represented as sets of ILR coordinates, and each composition was subtracted from the mean ILR coordinates to obtain the ILR differences. These ILR differences were used to determine the estimated difference (95% CI) for all outcomes. Ten minutes was determined as the minimum threshold for activity to impact health40, and thus, this study chose to use 10 min as the duration for reallocation to identify the minimal benefits derived from the reallocation of various activities.

Furthermore, we repeated the modeling process for those models where the 10-minute reallocation significantly impacted the outcome indicators. The dose-response relationship of mutual reallocation of movement behaviours and outcome indicators was explored in increments of five minutes and continued for longer periods, up to 30 min41.

Results

Participants information and covariate screening

After statistical analysis of participants’ information (Table 1), it was found that sex was a relevant factor for hyperactivity (t = 2.36, P = 0.02), externalizing difficulties (t = 2.34, P = 0.02), pro-sociality (t=-2.11, P = 0.04), height (t = 2.18, P = 0.03), weight (t = 1.16, P = 0.01), BMI (t = 2.15, P = 0.03), grip strength (t = 5.99, P < 0.001), standing long jump (t = 3.35, P = 0.001), and sitting forward bending (t=-3.94, P < 0.001). Therefore, sex will be used as a covariate for the above outcome indicators when establishing a linear regression model in the follow-up.

The area is a relevant factor for emotional symptoms (t=-2.05, P = 0.04), pro-sociality (t = 3.31, P = 0.001), grip strength (t=-5.34, P < 0.001), 15-metre obstacle running (t = 4.05, P < 0.001), walking on the balance beam (t = 2.99, P = 0.003), and physical fitness score (t=-2.21, P = 0.03). Therefore, area will be used as a covariate for the above outcome indicators when establishing a linear regression model in the follow-up.

Age is a relevant factor for height (F = 0.38, P < 0.001), weight (F = 35.44, P < 0.001), grip strength (F = 25.36, P < 0.001), standing long jump (F = 72.29, P < 0.001), two-legged continuous jump (F = 29.20, P < 0.001), 15-metre obstacle running (F = 40.95, P < 0.001), walking on the balance beam (F = 17.77, P < 0.001), body shape score (F = 4.19, P = 0.006), and physical fitness score (F = 4.48, P = 0.004). Therefore, age will be used as a covariate for the above outcome indicators when establishing a linear regression model in the follow-up.

The mental level is a relevant factor for emotional symptoms (F = 134.93, P < 0.001), peer problems (F = 33.37, P < 0.001), internalizing difficulties (F = 156.07, P < 0.001), conduct problems (F = 77.42, P < 0.001), hyperactivity (F = 35.16, P < 0.001), externalizing difficulties (F = 87.96, P < 0.001), and SDQ-Total-Difficulties (F = 208.78, P < 0.001). Therefore, mental level will be used as a covariate for the above outcome indicators when establishing a linear regression model in the follow-up.

Compositional analysis result

Dispersion analysis result

According to the variation matrix (Table 2), In structured PA, the structured MVPA and structured SB have the largest variance (2.52), indicating that these two activities have low correlation; while the structured MVPA and structured LPA have the smallest variance (0.72), indicating that these two activities have high correlation. In unstructured PA, the unstructured MVPA and unstructured SB have the largest variance (2.04), indicating that these two activities have low correlation; while the unstructured MVPA and unstructured LPA have the smallest variance (0.54), indicating that these two activities have high correlation.

Sleep exhibits high variance with other activity behaviours, therefore, sleep behaviour has low correlation with other activities and is not easily influenced.

Compositional analysis

Based on the previous screening of covariates, we used different adjustment variables for different outcome indicators. The final multiple linear regression models established all had significant model fitness (except BMI) (Table 3).

The results showed that in structured activities, structured MVPA was positively correlated with emotional symptoms (β=-0.74, P = 0.01), internalising difficulties (β=-0.87, P = 0.03), height (β = 2.89, P = 0.01), and body shape score (β = 2.17, P = 0.01). Structured LPA was negatively correlated with emotional symptoms (β = 1.09, P = 0.01), internalising difficulties (β = 1.52, P = 0.01), total difficulties (β = 1.74, P = 0.04), height (β=-3.53, P = 0.01), body shape score (β=-2.92, P = 0.008), and 15-meter obstacle running (β = 0.72, P = 0.04). Structured SB was negatively correlated with pro-sociality (β=-1.61, P = 0.04), height (β=-2.60, P = 0.04), grip strength (β=-1.54, P = 0.01), standing long jump (β=-10.53, P = 0.01), seating forward bending (β=-3.73, P = 0.01), and physical fitness score (β=-6.43, P = 0.01).

In unstructured activities, unstructured MVPA was positively correlated with emotional symptoms (β=-0.92, P = 0.01) and internalising difficulties (β=-1.24, P = 0.01). Unstructured LPA was negatively correlated with emotional symptoms (β = 0.90, P = 0.03). Unstructured SB was negatively correlated with emotional symptoms (β = 1.12, P < 0.001), internalising difficulties (β = 1.55, P < 0.001), height (β=-3.60, P = 0.003), body shape score (β=-2.24, P = 0.01), and standing long jump (β=-10.54, P = 0.01).

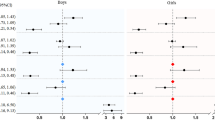

Isotemporal reallocation analysis result

Changes in preschooliers’ mental and physical as a result of 10-min isotemporal reallocation

Table 4 presents the estimated differences in mental and physical outcomes for reallocations of 10 min between time-use behaviours. Replacing 10 min of structured SB (SMD=-0.55, 95%CI: -1.08 to -0.01; SMD = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.18 to 1.64), structured LPA (SMD=-1.28, 95%CI: -2.30 to -0.27; SMD = 1.76, 95%CI: 0.37 to 3.15), unstructured SB (SMD=-0.63, 95%CI: -1.17 to -0.08; SMD = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.21 to 1.71), unstructured LPA (SMD=-0.66, 95%CI: -1.18 to -0.14; SMD = 1.09, 95%CI: 0.37 to 1.81), and sleep (SMD=-0.60, 95%CI: -1.14 to -0.06; SMD = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.19 to 1.67) with 10 min of structured MVPA can significantly improve internalizing difficulties and body shape in preschoolers.

Replacing 10 min of structured LPA with 10 min of unstructured MVPA can effectively improve internalizing difficulties (SMD=-0.80, 95%CI: -1.31 to -0.29), total difficulties (SMD=-0.94, 95%CI: -1.76 to -0.12), body shape (SMD = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.30 to 1.69), and physical fitness (SMD = 1.52, 95%CI: 0.06 to 2.98) in preschoolers.

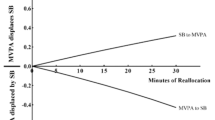

The dose-response benefits of reallocating structured MVPA time to other physical activity behaviours

Among the significant results based on 10-minute reallocations, structured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was found to be more effective in reallocating time compared to other reallocation models. Therefore, models were constructed sequentially with a 5-minute increment up to 30 min of reallocation, to obtain the health dose-response benefits of replacing other activities with structured MVPA time.

As shown in Fig. 3, the time reallocation of structured MVPA is associated with lower internalizing difficulties and better body shape scores. The more time other activities allocate to structured MVPA, the better the improvement effect. Among them, increasing structured MVPA time and reducing structured LPA time have significantly better effects on improving internalizing difficulties and body shape scores of preschoolers than other activity reallocations. Moreover, when the reallocation time reaches 25 min, there is a more significant improvement in benefits.

On the contrary, if structured MVPA is replaced by other activities, there is a downward trend in internalizing difficulties and body shape scores. Moreover, this deterioration occurs faster than the benefits gained from increasing structured MVPA time.

Discussion

This study not only analyses the relationship between structured and unstructured activities and the mental and physical health of preschoolers, but also determines the different health benefits of reallocation between structured and unstructured activities through the redistribution of time.

The relationship between different activities and mental and physical health of preschoolers

The relationship between different activities and mental health of preschoolers

The results of this study showed that both structured and unstructured MVPA had a positive effect on reducing emotional symptoms (β=-0.74, P = 0.01; β=-0.87, P = 0.03) and internalizing difficulties among preschoolers (β=-0.92, P = 0.01; β=-1.24, P = 0.01). These findings are consistent with previous studies, suggesting that more active children tend to exhibit better emotional health42,43. Research believes that preschoolers engaging in MVPA are in a state of extreme excitement or full activity44. During this process, the brain increases the secretion of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, which can greatly improve emotional45. Children in a better emotional state will behave more actively46. It can thus be inferred that there is a spiral relationship between the two, mutually reinforcing each other. By comparing the correlation coefficients, it can be observed that unstructured MVPA may have a more pronounced effect in ameliorating internalizing difficulties among preschoolers compared to structured MVPA (unstructured β: -1.24 > structured β: -0.87). In unstructured activities, children autonomously choose the content of their activities, largely satisfying their own interests and passions47. Systematic review studies have further demonstrated that unstructured play activities can improve mental issues among preschoolers25, emphasizing the potential for these activities to have an even more positive impact on addressing mental health concerns in this age group.

On the other hand, the results of this study showed that there were some negative impacts of structured and unstructured activities on the mental health of preschoolers. Structured LPA (β = 1.09, P = 0.01), unstructured SB (β = 1.12, P < 0.001) and LPA (β = 0.90, P = 0.03) had a negative effect on the emotional symptoms of preschoolers. Studies have found that children lacking in MVPA have significant deficiencies in self-efficacy, independence and sense of achievement48. Moreover, the decrease of serotonin secretion further aggravates emotional symptoms in preschoolers49. Coupled with the lack of positive play and interaction with teachers, and without the relief from peers or caregivers, insufficient activities and deterioration of emotional symptoms will further continue in a vicious cycle50. Therefore, how to mobilize such preschoolers to participate in more active groups or games is worthy of further study.

In addition, this study did not find that 24-hour activity behaviour was related to conduct problems, hyperactivity, and externalizing difficulties in preschoolers. The fundamental reason is that mental problems such as conduct problems, hyperactivity, and externalizing difficulties are actually manifested in the form of activities. For example, hyperactive children usually show long-term MVPA in real life51. Therefore, activity behaviour may not be used as a relevant indicator of externalizing difficulties in preschoolers.

The relationship between different activities and physical health of preschoolers

Unlike mental indicators, for the physical indicators, only structured MVPA had a positive effect on body shape in preschoolers. Previous studies have supported the favourable effect of MVPA on preschoolers’ body52,53. And this study further found that structured MVPA had a significant positive effect on preschoolers’ body shape, while unstructured MVPA did not show a significant effect. It is suggested that the health effects of MVPA on preschoolers’ fitness are mainly due to structured activity components with specific purposes and clear rules. In contrast, the more random unstructured activity component with no specific purpose and diverse forms and rules did not play a significant role, which may be related to the clustering characteristics of unstructured MVPA. Due to the constraints of the structured activity programme in kindergartens, preschoolers’ unstructured activities often take place in between lessons of short duration, and unstructured MVPA occurs sporadically and briefly on top of unstructured LPA, which needs to be accumulated over a longer period of time in order to have a significant benefit on physical health54,55.

Unfortunately, the results of this study did not show a correlation between either structured or unstructured MVPA and the physical fitness of preschoolers. Similar studies have consistently indicated that MVPA can effectively promote physical health in preschoolers, including cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, agility, and flexibility12. The reason for the results of this study may be that by categorizing MVPA into structured and unstructured types, the cumulative health benefits of MVPA were weakened. Additionally, during the period of this study, COVID-19 was prevalent, and kindergartens significantly reduced sports skill-based physical education classes to avoid excessive cross-contact between classes, instead increasing indoor music clapping or calisthenics classes. This further diminished the impact of MVPA on physical fitness.

In addition, SB or LPA has been shown to have negative outcomes with emotional difficulties and depression in preschoolers7,56. This study further found that unstructured SB, structured LPA, and unstructured LPA had significant negative effects on preschoolers’ emotional problems. Specifically, SB generated during unstructured activities in real contexts is mostly free and undisciplined screen time conducted by preschoolers, who are not able to filter and carry out educationally meaningful screen content, and are more attracted by the form and have difficulty in receiving positive guidance57. The cause of the negative effects of structured LPA and unstructured LPA in preschoolers may be related to the inhibition of MVPA effects. The relatively fixed daily activity time of preschoolers was accompanied by a relative increase in the proportion of LPA and a relative decrease in the proportion of MVPA, which suppressed the dosage effect of MVPA on preschoolers’ mental.

The relationship between the reallocation of time on different activities and mental and physical health of preschoolers

Results of the isotemporal reallocation model show that. Both internalizing difficulties and body shape were significantly improved in preschoolers using 10 min structured MVPA isotemporal reallocation for structured LPA, structured SB in structured activity behaviour. From the results of this study, it is critical that preschoolers’ interactive and physical education programmes, as the main carriers of structured MVPA, rationally allocate the activity time for their different intensity contents. For the interactive curriculum, the creation of structured MVPA signalled that preschooler invested a higher level of energy in interacting with their teachers or peers. This MVPA is directly linked to preschoolers’ internalising difficulties58. Meanwhile, SB was restricted during the interactive sessions. When SB was controlled, MVPA showed a significant correlation with internalisation difficulties59. Therefore, how to increase preschoolers’ motivation during interactive sessions is an effective way to improve preschoolers’ internalising difficulties. And for preschoolers’ physical education curriculum system. With a relatively fixed curriculum time, increasing the relative proportion of structured MVPA in structured PA and decreasing the relative proportion of structured LPA and structured SB remains an optimal solution for improving preschoolers’ bodies. Among the other isotemporal reallocations for structured MVPA, both unstructured SB and unstructured LPA and SP, preschoolers’ internalising difficulties were significantly reduced and body shape was significantly enhanced. This further illustrates the importance of S-MVPA for preschoolers’ body and mind. The trend of isotemporal reallocation effect shows that the amount of health effect of structured MVPA on preschoolers’ body and mind gradually increased with the increase of reallocation time. A rapid decline was observed at reverse reallocation. This trend is consistent with the previous trend of MVPA-based isotemporal reallocation, which shows an asymmetry of isotemporal reallocation benefits9,60,61. Meanwhile, when the time of structured MVPA reallocation for structured LPA was increased to 25 min, the internalising difficulties score and body shape score of preschoolers showed a sharp inflection point. This suggests that 25 min may be the “health threshold” for structured MVPA isotemporal reallocation and structured LPA.

Advantages and limitations

The varying proportions or doses of structured and unstructured activities have distinct health benefits for preschoolers’ mental and physical health. However, there is a lack of research evidence in this area. Therefore, this study is the first to reveal the impact of structured and unstructured activities on preschoolers’ mental and physical health within a 24-hour activity pattern using compositional data analysis and isotemporal reallocation modelling. The findings of this study fill the gap in current research and simultaneously provide a more health-beneficial intervention strategy.

While this study rigorously adhered to the study design and employed scientific and detailed statistical analyses to create models, there are certain limitations to be acknowledged. On one hand, the regional characteristics and environmental backgrounds of the sample participants may limit the generalizability of the study findings, suggesting a need for broader sample representation. On the other hand, this study analysed cross-sectional data results, necessitating longitudinal research to establish causal relationships between structured and unstructured activity behaviours and the physical and mental health of preschoolers. On the other hand, this study is a cross-sectional study, and further longitudinal research and randomized controlled trials are needed to establish a causal relationship between structured and unstructured physical activity behaviours and preschoolers’ mental and physical health. Additionally, observational studies cannot control for all potential confounding variables, thus posing a risk of residual confounding.

Conclusion

Structured MVPA can effectively improve emotional symptoms, internalizing difficulties, and body shape among preschoolers. Meanwhile, Unstructured MVPA demonstrates superior results in ameliorating emotional symptoms and internalizing difficulties. By maintaining the duration of structured activities and increasing the proportion of MVPA within these activities, while simultaneously decreasing the proportion of LPA or SB, it is possible to effectively optimize preschool curricula, leading to improved internalizing difficulties and physical outcomes. Ideally, this transition should occur for a duration of over 25 min. Additionally, incorporating unstructured MVPA into curricula can further alleviate internalizing difficulties among preschoolers. It is recommended that teachers and caregivers encourage preschoolers to engage in vigorous activities as much as possible during their academic life, rather than waiting, instructing them how to do it, limiting risks, or engaging in other activities that hinder the development of MVPA.

Data availability

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- S-PA:

-

Structured physical activity

- US-PA:

-

Unstructured physical activity

- LPA:

-

Light-intensity physical activity

- S-LPA:

-

Structured light-intensity physical activity

- US-LPA:

-

Unstructured light-intensity physical activity

- MVPA:

-

Moderate to vigorous physical activity

- S-MVPA:

-

Structured moderate to vigorous physical activity

- US -MVPA:

-

Unstructured moderate to vigorous physical activity

- SB:

-

Sedentary behaviour

- S-SB:

-

Structured sedentary behaviour

- US-SB:

-

Unstructured sedentary behaviour

- SP:

-

Sleep

- SOPARC:

-

System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- DQ:

-

Developmental Quotient

- EDI:

-

Equity, Diversity, Inclusion

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- M:

-

Mean

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SMD:

-

Standard Mean Difference

- CI:

-

Credible Intervals

References

Mackie, P. & Sim, F. Improving the health of children and young people: the World Health Organization Global Schools Health Initiative twenty-three years on. Public. Health 159, A1–A3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.012 (2018).

Kieling, C. et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 378, 1515–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60827-1 (2011).

Wang, Y. & Lim, H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 24, 176–188. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.688195 (2012).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6, 168–176 (2007).

Must, A. & Strauss, R. S. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord 23(Suppl 2), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0800852 (1999).

Yang, L., Corpeleijn, E. & Hartman, E. A prospective analysis of physical activity and mental health in children: the GECKO drenthe cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 20, 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-023-01506-1 (2023).

O’Brien, K., Agostino, J., Ciszek, K. & Douglas, K. A. Physical activity and risk of behavioural and mental health disorders in kindergarten children: analysis of a series of cross-sectional complete enumeration (census) surveys. BMJ Open. 10, e034847. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034847 (2020).

Fitzgerald, S. A., Fitzgerald, H. T., Fitzgerald, N. M., Fitzgerald, T. R. & Fitzgerald, D. A. Somatic, psychological and economic benefits of regular physical activity beginning in childhood. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 58, 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15879 (2022).

Lemos, L. et al. 24-hour movement behaviors and fitness in preschoolers: a compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 31, 1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13938 (2021).

Bezerra, T. A. et al. 24-hour movement behaviour and executive function in preschoolers: a compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 21, 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1795274 (2021).

Fairclough, S. J. et al. Fitness, fatness and the reallocation of time between children’s daily movement behaviours: an analysis of compositional data. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phy. 14 ARTN 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0521-z. (2017).

Song, H. et al. 24-H movement behaviors and physical fitness in preschoolers: a compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 22, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2024.03.002 (2024).

Lau, P. W. C. et al. 24-Hour movement behaviors and executive functions in preschoolers: a compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. Child. Dev. 95, e110–e121. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14013 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Reallocation of time between preschoolers’ 24-h movement behaviours and executive functions: a compositional data analysis. J. Sports Sci. 41, 1187–1195. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2023.2260632 (2023).

Mota, J. G. et al. Twenty-four-hour movement behaviours and fundamental movement skills in preschool children: a compositional and isotemporal substitution analysis. J. Sports Sci. 38, 2071–2079. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1770415 (2020).

Fu, J. et al. Relationship between 24-h activity behavior and body fat percentage in preschool children: based on compositional data and isotemporal substitution analysis. Bmc Public. Health. 24, 1063. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18570-2 (2024).

St Laurent, C. W., Burkart, S., Rodheim, K., Marcotte, R. & Spencer, R. M. C. Cross-sectional associations of 24-hour sedentary time, physical activity, and sleep duration compositions with sleep quality and habits in preschoolers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197148 (2020).

Chang, Z. & Wang, S. Research on the Isochronous substitution benefit of activity behavior on the mental health of 3–6 year old preschool children. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 37, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2022.03.018 (2022).

World Health, O. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of age (World Health Organization, 2019).

Clark, J. E. et al. Active Start: A Statement of Physical Activity Guidelines for Children Birth to Five Years (ERIC, 2002).

Katzmarzyk, P. T. et al. Results from the United States 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Activity Health 15, S422–S424 (2018).

Chen, D. et al. Effects of structured and unstructured interventions on fundamental motor skills in preschool children: a meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health 12, 1345566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1345566 (2024).

Mačak, D. et al. The effects of daily physical activity intervention on physical fitness in preschool children. J. Sports Sci. 40, 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1978250 (2022).

Yu, C. C. W., Wong, S. W. L., Lo, F. S. F., So, R. C. H. & Chan, D. F. Y. Study protocol: a randomized controlled trial study on the effect of a game-based exercise training program on promoting physical fitness and mental health in children with autism spectrum disorder. BMC Psychiatry 18, 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1635-9 (2018).

Lee, R. L. T. et al. Systematic review of the impact of unstructured play interventions to improve young children’s physical, social, and emotional wellbeing. Nurs. Health Sci. 22, 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12732 (2020).

Wasenius, N. et al. Unfavorable influence of structured exercise program on total leisure-time physical activity. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 24, 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12015 (2014).

Minghui, Q. et al. Research progress on the influence of physical activity on cognitive ability and its mechanism. Sports Sci. 34, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.2014.09.001 (2014).

Province, P. s. G. o. J. (People’s Government of Jiangxi Province, 2022).

Butte, N. F. et al. Prediction of energy expenditure and physical activity in preschoolers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 46, 1216–1226. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000209 (2014).

Choi, L., Liu, Z., Matthews, C. E. & Buchowski, M. S. Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed61a3 (2011).

Howe, C. A., Clevenger, K. A., Plow, B., Porter, S. & Sinha, G. Using video direct observation to assess children’s physical activity during recess. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 30, 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2017-0203 (2018).

McKenzie, T. L., Cohen, D. A., Sehgal, A., Williamson, S. & Golinelli, D. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. J. Phys. Act. Health 3(Suppl 1), S208-s222 (2006).

Ferreira, T. et al. The strengths and difficulties Questionnaire: an examination of factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity using multitrait-multirater data. Psychol. Assess. 33, 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000961 (2021).

Jianhua, K., Yasong, D. & Liming, X. Reliability and validity of the Shanghai norm of the strengths and difficulties Questionnaire (parent version). Shanghai Psychiatry 01, 25–28 (2005).

China, G. A. o. S. (General Administration of Sport of China, 2023).

Aitchison, J. The statistical analysis of compositional data. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 44, 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1982.tb01195.x (2018).

Chastin, S. F., Palarea-Albaladejo, J., Dontje, M. L. & Skelton, D. A. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS ONE. 10, e0139984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139984 (2015).

Pawlowsky-Glahn, V., Egozcue, J. J. & Tolosana-Delgado, R. Modeling and Analysis of Compositional data (Wiley, 2015).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression (Sage, 2018).

in Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health (World Health Organization Copyright © World Health Organization 2010., 2010).

Dumuid, D. et al. The compositional isotemporal substitution model: a method for estimating changes in a health outcome for reallocation of time between sleep, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 28, 846–857. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280217737805 (2019).

Bell, S. L., Audrey, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, A. & Campbell, R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Associations of emotional/behavioral problems with accelerometer-measured sedentary behavior, physical activity and step counts in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Public. Health. 10, 981128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.981128 (2022).

World Health, O. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour (World Health Organization, 2020).

Voss, M. W., Nagamatsu, L. S., Liu-Ambrose, T. & Kramer, A. F. Exercise, brain, and cognition across the life span. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 111, 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00210.2011 (2011).

Kopp, P. M., Möhler, E. & Gröpel, P. Physical activity and mental health in school-aged children: a prospective two-wave study during the easing of the COVID-19 restrictions. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment Health. 18, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00695-8 (2024).

Coffino, J. R. & Bailey, C. The Anji play ecology of early learning. Child. Educ. 95, 3–9 (2019).

Paluska, S. A. & Schwenk, T. L. Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. Sports Med. 29, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003 (2000).

Wipfli, B., Landers, D., Nagoshi, C. & Ringenbach, S. An examination of serotonin and psychological variables in the relationship between exercise and mental health. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 21, 474–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01049.x (2011).

Zink, J. et al. Patterns of objectively measured sedentary time and emotional disorder symptoms among Youth. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 47, 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsac014 (2022).

Yu, C. L. et al. Motor competence moderates relationship between moderate to vigorous physical activity and resting EEG in children with ADHD. Ment. Health. Phys. Act. 17, 100302 (2019).

Elmesmari, R., Martin, A., Reilly, J. J. & Paton, J. Y. Comparison of accelerometer measured levels of physical activity and sedentary time between obese and non-obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 18, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1031-0 (2018).

Guanggao, Z. et al. The effect of physical activity on the physical growth of preschool children. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 41, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.16099/j.sus.2017.04.011 (2017).

Holman, R. M., Carson, V. & Janssen, I. Does the fractionalization of daily physical activity (sporadic vs. bouts) impact cardiometabolic risk factors in children and youth? PLoS ONE. 6, e25733. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025733 (2011).

Minghui, Q., Chunyi, F., Yi, Z., Longkai, L. & Peijie, C. A dose-effect relationship study of physical activity and physical fitness in preschool children with different cluster characteristics. Sports Sci. 40, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.202003004 (2020).

Rodríguez-Hernández, A., Cruz-Sánchez Ede, L., Feu, S. & Martínez-Santos, R. [Inactivity, obesity and mental health in the Spanish population from 4 to 15 years of age]. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 85, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1135-57272011000400006 (2011).

Robidoux, H., Ellington, E., Lauerer, J. S. & Time The impact of Digital Technology on children and strategies in Care. J. Psychosoc Nurs. Ment Health Serv. 57, 15–20. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20191016-04 (2019).

Tang, Y., Algurén, B., Pelletier, C., Naylor, P. J. & Faulkner, G. Physical literacy for communities (PL4C): physical literacy, physical activity and associations with wellbeing. BMC Public. Health 23, 1266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16050-7 (2023).

Page, A. S., Cooper, A. R., Griew, P. & Jago, R. Children’s screen viewing is related to psychological difficulties irrespective of physical activity. Pediatrics 126, e1011-1017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1154 (2010).

Kuzik, N., Naylor, P. J., Spence, J. C. & Carson, V. Movement behaviours and physical, cognitive, and social-emotional development in preschool-aged children: cross-sectional associations using compositional analyses. PLoS ONE 15, e0237945. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237945 (2020).

Fairclough, S. J. et al. Fitness, fatness and the reallocation of time between children’s daily movement behaviours: an analysis of compositional data. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 14, 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0521-z (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Nanchang University, Jiangxi Sports Science Medical Centre, Jiangxi Normal University, and Beijing Sport University for their invaluable support in this research endeavour. Furthermore, we extend our deepest appreciation to the National Social Science Foundation and Jiangxi Provincial Foundation for their generous financial support. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge all the esteemed authors for their commendable contributions to this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (21BTY088), the 14th Five-Year Plan of Social Science in Jiangxi Province (22TY20D), the Special Project for Postgraduate Students’ Innovation in Jiangxi Province (YC2021-S024), and the Special Project for Postgraduate Students’ Innovation in Jiangxi Province (YC2022-S031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C. wrote the article, and G.Z. revised it. J.F., S.S., L.S., and Z.H. provided ideas for the modifications, and R.C., X.H., T.J., Y.L., and F.S. assisted in the use of the software. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. ID number: research clinical review [2020] No. (125). The government approval document: Jiangxi Provincial Sports Bureau Document. ID number: Gan Ti Qun Zi [2021] No. 1.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Zhao, G., Fu, J. et al. Structured-unstructured activity behaviours on preschoolers’ mental and physical health: a compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. Sci Rep 14, 24219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74882-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74882-8