Abstract

A study of velocity distribution function in Earth’s magnetosphere is conducted using high-resolution measurements from the Magnetospheric Multiscale Spacecraft (MMS). The analysis focuses on the AZ-non-Maxwellian distribution that is a complex velocity-space structure, exhibiting a power-law distribution of moments. By imposing constraints on the spectral indices of the AZ-velocity distribution, the most suitable distribution for modeling Earth’s magnetosphere is determined. The combined use of MMS data and analysis of velocity distribution provides new insights into the behavior of plasma particles and the velocity space structures responsible for energy dissipation in plasmas. Understanding particle distribution, behavior, and the influence of cold ions in Earth’s magnetosphere is crucial for advancing our knowledge of plasma physics and has practical implications for space weather and magnetospheric dynamics. Addressing the remaining uncertainties and challenges in measurements, analysis of non-Maxwellian distribution of ions is essential for a comprehensive understanding of space plasma environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Withinthe magnetospheric plasmas, particle populations span a wide energy spectrum, encompassing electron volt particles from the ionosphere and plasmasphere to highly energetic particles found in the radiation belts1. These varied particle assemblies coexist and engage in interactions facilitated by a range of plasma waves2. The magnetosphere of Earth contains numerous collections of cold ions and electrons that are lacking detailed characterization and leaving their full influence on the magnetospheric system, still not understood comprehensively. Cold plasma mainly comprises protons and electrons, forming the plasmasphere. This region is characterized by its low energy (< 100 eV) ions which drift with certain velocities within the magnetosphere. Other ions like He+ and heavier species contribute moderately. Cold ions have origin from the topside ionosphere flowing into the magnetosphere, including a mix of H+, He+, O+, and N+3. These ions contribute significantly to geospace dynamics to exhibit suprathermal outflows with accelerated velocities. Though not traditionally considered cold, the solar wind consists of primarily electrons and protons with temperatures around 10 eV4. Upon crossing the bow shock, temperatures in the magnetosheath rise before cooling off as they move to the nightside. This region serves as an entry mechanism for plasma into the magnetosphere. Cold ions significantly impact magnetospheric dynamics and influencing the plasma distribution, temperature, density, and mass profiles in different regions of the magnetosphere. Cold ions can be transformed into the hot magnetospheric plasma under certain conditions. Studies show that ionospheric outflows not only act as a source of plasma but also affect magnetospheric dynamics, influencing phenomena like the ring current, magnetotail behavior, and geomagnetic storms. Observing and measuring cold ions are the key challenges due to their low energies (below 100 eV). Improved measurement techniques are needed to fully understand their distribution and behavior. Despite progress, several unknowns persist, such as the exact mechanisms of ionospheric outflow, the balance between solar wind and ionospheric sources, and the influence of various factors like geomagnetic activity and solar conditions on plasma distribution.

The constituents of the plasma (such as electrons, negative/positive ions, etc.) constantly interact or collide with each other and move at varying velocities. Due to these interactions, the plasma particles may exchange their kinetic energy (K.E.) and momentum (P) to reach a thermal equilibrium. Maxwellian distribution is typically used for characterizing the plasma particles in a thermal equilibrium5,6. When the velocities of the plasma particles become higher than their thermal velocities, the conventional Maxwellian distribution cannot explain the behavior of high velocity plasma particles. Consequently, numerous non-Maxwellian distributions are suggested to model energetic particles, inspecting for composite plasma environments. The transition from Maxwellian to non-Maxwellian plasmas is due to the long-range particle interactions (such as gravitational, and Coulombic) that could be plausible possibility for the source of this phenomenon7,8and spatial fluctuation of physical parameters, including density, magnetic field strength and temperature, both in laboratory and astrophysical plasmas9. The external field might cause particle flows and turbulence that can be measured as quasi-steady state10and also responsible for this deviation. So, it is commonly observed in many space environments where plasma particles follow a non-Maxwellian distribution showing high energetic particles on the tails and significant changes on the shoulders and/or on top shoulders. The non-Maxwellian distribution has been used to give a satisfactory fitting for the magnetosheath electron11and solar wind proton12 data from the AMPTE satellite and CLUSTER, respectively.

More than 50 years ago, it was suggested that non-Maxwellian distributions are caused by wave-particle energy exchanges13, which are crucial in different laboratory14and space plasma events15. Wave-particle interactions are essential for various applications in laboratory plasmas, including beat wave acceleration, plasma heating from radio waves at ion and electron cyclotron frequencies, and transport losses due to edge turbulence16. In the realm of space, plasmas exhibit the formation of the magnetopause boundary layer, the generation of plasmaspheric hiss emissions, the electron-magnetic outer ozone chorus as well as the precipitation of particles leading to the occurrence of auroras, among other processes. Low-frequency waves interact with charged particles over broad spatial scales, distributing their energy across the magnetosphere. The interaction of ion cyclotron and whistler mode waves with particles in the Van Allen belt results the dispersion of energetic protons and electrons into the loss cone. This process contributes to the decay of the ring current during the recovery phase of a magnetic storm. Electrons can be precipitated through the pitch angle scattering, resulting from the cyclotron resonance between outer zone whistler mode chorus and trapped substorm electrons within the energy levels ranging from 10 to 100 keV13. Fluctuations in velocity space reflect another crucial aspect of plasma dynamics, and they accompany spatial changes in a weakly collisional plasma14.

The velocity distribution of particles in the magnetosphere and space plasmas perform an essential part in understanding the dynamic and complex nature of these environments. The velocity distribution of particles can influence the occurrence and properties of plasma waves and instabilities. Understanding these phenomena is vital for comprehending the energy transfer and wave-particle interactions in the magnetosphere2. Moreover, the velocity distribution affects the dynamics of fundamental processes and magnetic reconnection in space plasmas that releases magnetic energy and drives various space weather phenomena15. The study of velocity distribution provides new insights into the mechanisms that are responsible for the particle heating and acceleration, crucial for understanding the creation of high-energy particles in space plasmas16. Furthermore, the velocity distribution of solar wind particles governs the interaction with the Earth’s magnetosphere, influencing magnetospheric dynamics, geomagnetic storms, and substorms1. The velocity distribution of solar wind and magnetospheric particles affects the space weather phenomena, such as geomagnetic storms and auroras, which can have significant impact on technological systems4. Understanding the velocity distribution in magnetosphere and space plasmas is an interdisciplinary effort, involving the plasma physics, space physics, and astrophysics.

Vasyliunas17was the first who analyzed the electron energy spectrum of space plasma magnetic shoes and presented a kappa-distribution function for high-energy electron velocities. Later, a variety of non-thermal velocity distribution functions such as Cairns distribution18, two spectral index Vayliunas-Cairns distribution19, generalized Cairns-Tsallis distribution20, and (r, q)-distribution17were incorporated to model plasma wave dynamics. A more generalized three-parameter non-Maxwell AZ-velocity distribution21was proposed to study diverse linear and nonlinear waves in space plasmas, such as solar wind11, magnets12, and aurora belts22. The measurement of velocity space posed many challenges in both simulations and experiments with recent Vlasov simulations revealing the intricate nature of velocity space, mirroring observed patterns near real conditions21,23,24,25,26. In this paper, we focus on the findings of Kitamura et al27, who conducted ultrafast measurements for Earth’s magnetosphere using the Magnetospheric Multiscale Spacecraft (MMS) observations. These measurements have provided a quantitative assessment for energy transfer during interactions related to electromagnetic ion-cyclotron waves. We utilize the AZ-distribution to model ions in the Earth’s magnetosphere observed on September 01, 2015 at different time scales: 12:17:10–12:17:20 UT, 12:17:20 − 12:17:50, 12:21:30 − 12:21:57 UT, 12:21:58 − 12:22:00UT and 12:22:01–12:22:30UT using the highly accurate data of the Magnetospheric Multiscale Spacecraft (MMS1). The latter solves a vital research problem regarding the plasma dynamics resulting in dissipation and heating. Moreover, a key breakthrough in this paper is the implementation of the AZ-distribution which is newly invented distribution function generalizing the various velocity distribution functions for space plasmas. By adopting this distribution, one can fit different distributions by adjusting their spectral indices. Once we understand which kind of distribution occurs in space, we can easily understand the exact mechanism of wave particle interactions by simulations for space plasmas.

Theoretical methodology

Abid et al22. have introduced a generalized groundbreaking power-law distribution to model energetic particles in space plasmas, known as the Abid Zubair (AZ)-distribution. This distribution is essentially based on three parameters, and not only converges to a variety of non-Maxwellian distributions such as (r, q)-distribution, q-nonextensive distribution, Vasyliunas-Cairns distribution, kappa distribution under specific parameter conditions but also reproduces the Maxwellian distribution. The AZ-distribution function21,28 for th space plasma species (electrons and ions) can be represented by.

where \(\:{V}_{j}\) (\(\:{V}_{Tj}=\sqrt{{T}_{j}/{m}_{j}})\) is the fluid (thermal) speed with \(\:{T}_{j}\left({m}_{j}\right)\) is the temperature (mass) of the jth species. Three spectral indices \(\:\alpha\:\) (energetic particles representing the shoulder), q (superthermal particle in the tail along the velocity distribution curve) and r (representing superthermal particles on the broad-shoulder) hold the limitations \(\:\alpha\:>0\:\)\(\:q>1\:\)and\(\:\:q\left(r+1\right)>5/2\). The normalization constant of the AZ-distribution function29can be calculated by the formula28\(\:4\pi\:{\int\:}_{0}^{\infty\:}{f}_{j}\left({V}_{j}\right){{V}_{j}}^{2}{dV}_{j}={n}_{j},\) as

with

and

The specific values of the indices\(\:\:\alpha\:\), r and q in the AZ-distribution function (1) reproduce various distributions in the limiting cases as: (i) (r, q)-distribution17 for \(\:\alpha\:=0\), (ii) Vasyliunas-Cairns distribution19 for \(\:r\to\:0\) and \(\:q=\kappa\:+1\)(iii) Cairns distribution18 for \(\:q\to\:\infty\:\) and \(\:r\to\:0,\:\)(iv) kappa velocity distribution30 for \(\:\alpha\:\to\:0,\)\(\:r\to\:0,\) and \(\:q=\kappa\:+1\)(v) and finally the Maxwellian distribution6 for \(\:\alpha\:\to\:0,\)\(\:r\to\:0,\) and \(\:q\to\:\infty\:\).

MMS observation

The Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) spacecraft was launched into an elliptical equatorial orbit on March 12, 2015 with a geocentric apogee of 12 Earth radii (RE) and a perigee of 1.2RE27. The four MMS satellites are arranged in almost regular tetrahedral structure, each equipped similarly. The measurements conducted by the MMS exhibit changes in accuracy and time resolution compared to previous magnetospheric missions31. These measurements with high time resolution include particles, fields, and waves32. In this study, the measurements from Fast Plasma Investigation (FPI) instrument aboard MMS1 (https://lasp.colorado.edu/mms/sdc/public/about/browse-wrapper/) have been utilized. The FPI instrument is mounted on the MMS spacecraft which provides high time resolution measurement of the ion and electron velocity distributions (VDFs)27. The analysis in this study utilizes the data captured from 2015-09-01/12:17:07 UT to 2015-09-01/12:22:20 UT, referencing an event extracted from the recent work of Kitamura et al28. Using the FPI-DIST burst data, the ion velocity distributions are observed across different time intervals and measurement points are depicted by using xy slices (where the x-axis aligns with the data’s x-axis and y corresponds to the data’s y-axis).

Theoretical and observation results

The main objective of the work under consideration is to analyze the AZ-distribution for space plasmas. It is well-known that the velocity distribution function plays an essential part in studying the processes of instabilities in space plasmas. The generalized AZ-distribution is a suitable model for analyzing MMS data to gain insights into the behavior of energetic particles in the magnetosphere. This novel distribution function could be a groundbreaking invention to address current challenges in measuring velocity space distribution in simulations and experiments, as suggested by many authors21,23,24,25,26.

The behavior of the AZ-distribution function [as given by Eq. (1)] is displayed in Fig. 1, which is significantly influenced by the three spectral indices (α, r, and q): α affects the rate of high energetic particles on the shoulder, r impacts the presence of energetic particles on a broad-shoulder, and q influences the superthermality on the tail and width of the distribution. An appropriate choice of these indices may lead to reproduction of various non-Maxwellian distributions and even Maxwellian distribution as well. Note that thick solid black curve corresponds to q = 2.5, r= 1.5, and α = 0.0, representing the impact of high-energy particles on the broad shoulder. This aligns well with the (r, q)-distribution functio11,17. The dashed blue curve (q = 20, r= 0.0, and α = 0.5) represents the Vasyliunas-Cairns distribution function19, while the dotted-dashed red curve (q = 20, r= 0.0, and α = 0.2) represents the Cairns distribution function18. The higher values of α signify a stronger influence of high-energy particles on the distribution curve’s shoulder. The green dotted-dotted-dashed curve (q = 8, r= 0.0, and α = 0.1) indicates to the Kappa distribution function30, emphasizing the presence of energetic particles at the tail of the curve. Finally, the AZ-distribution converges to a Maxwellian distribution6, can be seen in Fig. 1 by small dashed magenta curve (q = 30, r = 0, and α = 0).

The behavior of normalized AZ-distribution function vs. the normalized velocity: thick solid black curve (q = 2.5, r = 1.5, and α = 0) represents the (r, q)-distribution, dashed blue curve (q = 20, r = 0.0, and α = 0.5) agrees with Vasyliunas-Cairns distribution, dotted dashed red curve (q = 20, r = 0.0, and α = 0.2) represents Cairns distribution, dotted-dotted dashed green curve (q = 8, r = 0, and α = 0.1) shows Kappa distribution function, and dotted magenta curve (q = 30, r = 0, and α = 0) represents the Maxwellian distribution.

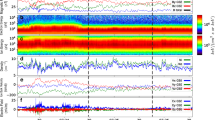

Figure 2 compares the results obtained by MMS data and theoretical AZ-distribution. It has been observed that distribution behavior is different during different time durations. Figure 2(a-c) and (d-f) shows the 3D and 2D ions velocity distributions at additional time ranges 12:17:10–12:17:19, 12:17:20 − 12:17:50 and 12:21:30 − 12:21:57 of the desired event (2015-09-01/12:17: 10 to 2015-09-01/12:22:30), respectively by adopting high resolution burst data of fast plasma investigation of MMS spacecraft. The ion velocity distribution is calculated by the field aligned coordinates (the axis aligns with the x-axis of the coordinates, and y corresponds to the y-axis of the coordinates). The bottom panel of Fig. 2(g-i) represents the behavior of the AZ-distribution function [as given by Eq. (1)] for varying the values of spectral indices \(\:\alpha\:,\:r\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q\). A comparison has been made between the velocity distribution curves obtained by the AZ-distribution function and those obtained by MMS data. Figure 2(d) shows that high energetic ions occur on the top shoulder of the distribution curve, qualitatively consistent with the result obtained by fixed values of spectral indices, such as\(\:\:\alpha\:=0.05\:,\:r=3.0\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q=3.0\). It has been shown that spectral index r is more prominent in this combination of spectral indices. The curve in Fig. 2(e) corresponds to MMS data during 12:17:20 − 12:17:50 almost agrees with the curve of Fig. 2(h) by using Eq. (1) for fixed values of spectral indices\(\:\:\alpha\:=0.2\:,\:r=0.1\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q=8.0\). It has been observed that during this particular part of the event [see Fig. 2(e)], the highly energetic particles appear on the tail of the distribution curves, which is further justified in Fig. 2(h) by AZ-distribution. The last column of Fig. 2 shows most likely a Maxwellian type of behavior both in observational and theoretical analyses. Figure 2(c) and Fig. 2(f) were generated by MMS data during 12:21:30 − 12:21:57 and same trend is found by Eq. (1) under the condition \(\:\alpha\:=0.0\:,\:r=0.3\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q=30\) [see Fig. 2(i)]. In a nutshell, Fig. 2 shows various ion distributions with different indices in space plasmas.

Ion velocity distribution functions obtained by MMS during different time intervals 12:17:10–12:17:19, 12:17:20 − 12:17:50 and 12:21:30 − 12:21:57 in the field aligned coordinate system for 3D (a-c), respectively. The (d-f) panel shows 2D curves for the same time intervals. Here, 2D panels are along the magnetic field direction, and (g-i) panel exhibits the AZ-distribution function curves under various limits of spectral indices.

Figure 3(a)-(c) is plotted by using MMS data from 12:21:58 − 12:22:00. It is observed that energetic ions appear more prominently on the shoulder of the distribution curve. It is additionally analyzed that the presence of energetic ions on the shoulder of the distribution curve appears only for 2 s. The AZ-distribution has produced the same result in Fig. 3(e) by using different value of three spectral indices (\(\:\alpha\:=0.25\:,\:r=0.0\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q=10\)). Figure 3(b-d) plotted during the 12:22:01–12:22:30 interval, the curve of ion distribution displays two peaks as shown in the Fig. 3(d), and AZ-distribution justifies this unique trend for the fixed values of spectral indices\(\:\:\alpha\:=1.3\:,\:r=0.15\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:q=7.0\) [see Fig. 3(f)].

Ion velocity distribution functions obtained by MMS during different time intervals 12:21:58 − 12:12:00 and 12:22:01–12:22:30 in the field-aligned coordinate system for 3D (a-b), respectively. The (c-d) panel shows 2D curves for the same time intervals. Here, 2D panels are along the magnetic field direction, and (e-f) panel exhibits the AZ-distribution function curves under various limits of spectral indices.

To conclude, we have analyzed ion velocity destitution in the magnetosphere of Earth by using data from MMS mission and a novel AZ-velocity-distribution. We have observed that energetic ions occur on the broad shoulder, shoulder, tail, and width of distribution curves during the EMIC wave event at 2015-09-01/12:17:10 to 2015-09-01/12:22:30 UT in the field-aligned coordinates. The transition of energetic ions on different regions of distribution curves occurs in one event. Applying various limitations on the spectral indices, one can justify the presence of AZ-velocity-distribution in the magnetosphere. The synergistic application of MMS datasets, innovative deployment of the AZ-distribution method, and the application of scaling theory to velocity introduce novel avenues for comprehending the behavior of plasma particles and the essential velocity space characteristics contributing to dissipation in plasmas.

Data availability

MMS data analyzed in the present study are publicly available via the MMS Science Data Center (SDC) (https://lasp.colorado.edu/ MMS/sdc/public/).

References

Russell, C. T. & Elphic, R. Initial ISEE magnetometer results: magnetopause observations. Space Sci. Rev. 22, 681–715 (1978).

Gary, S. P. Theory of Space Plasma Microinstabilities (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Stasiewicz, K. et al. Properties of fast magnetosonic shocklets at the bow shock. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30(24), 2241 (2003).

Schrijver, C. J. & Siscoe, G. L. Heliophysics: Space Storms and Radiation: Causes and Effects (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Krall, N. A. & Trivelpiece, A. W. Principles of Plasma Physics (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1973).

Chen, F. F. Introduction to Plasma Physics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Jiulin, D. Nonextensivity and the power-law distributions for the systems with self-gravitating long-range interactions. Astrophys. Space Sci. 312, 47–55 (2007).

Wu, J. & Chen, H. Fluctuation in nonextensive reaction–diffusion systems. Phys. Scr. 75, 722 (2007).

Zaheer, S., Murtaza, G. & Shah, H. Some electrostatic modes based on non-maxwellian distribution functions. Phys. Plasmas. 11, 2246–2255 (2004).

Treumann, R. A. Kinetic theoretical foundation of Lorentzian statistical mechanics. Phys. Scr. 59, 19 (1999).

Qureshi, M., Shi, J. & Ma, S. Landau damping in space plasmas with generalized (r, q) distribution function. Phys. Plasmas. 12, 122902 (2005).

Qureshi, M. N. S. et al. Solar wind particle distribution function fitted via the generalized kappa distribution function: Cluster observations. In AIP Conference Proceedings 679(1), 489–492 (American Institute of Physics, 2003).

Tsurutani, B. T. & Lakhina, G. S. Some basic concepts of wave-particle interactions in collisionless plasmas. Rev. Geophys. 35, 491–501 (1997).

Servidio, S. et al. Magnetospheric multiscale observation of plasma velocity-space cascade: Hermite representation and theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 205101 (2017).

Priest, E., & Forbes, T. Magnetic Reconnection: MHD Theory and Applications, 612 Cambridge (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Treumann, R. A. & Baumjohann, W. Collisionless magnetic reconnection in space plasmas. Front. Phys. 1, 31 (2013).

Rubab, N. & Murtaza, G. Dust-charge fluctuations with non-maxwellian distribution functions. Phys. Scr. 73, 178 (2006).

Cairns, R. et al. Electrostatic solitary structures in non-thermal plasmas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 2709–2712 (1995).

Abid, A., Ali, S., Du, J. & Mamun, A. Vasyliunas–Cairns distribution function for space plasma species. Phys. Plasmas. 22, 084507 (2015).

Williams, G., Kourakis, I., Verheest, F. & Hellberg, M. A. Re-examining the Cairns-Tsallis model for ion acoustic solitons. Phys. Rev. E. 88, 023103 (2013).

Parashar, T. N. & Matthaeus, W. H. Propinquity of current and vortex structures: effects on collisionless plasma heating. Astrophys. J. 832, 57 (2016).

Abid, A., Khan, M., Lu, Q. & Yap, S. A generalized AZ-non-Maxwellian velocity distribution function for space plasmas. Phys. Plasmas. 24, 033702 (2017).

Greco, A., Matthaeus, W., Servidio, S., Chuychai, P. & Dmitruk, P. Statistical analysis of discontinuities in solar wind ACE data and comparison with intermittent MHD turbulence. Astrophys. J. 691, L111 (2009).

Servidio, S., Valentini, F., Califano, F. & Veltri, P. Local kinetic effects in two-dimensional plasma turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 045001 (2012).

Greco, A., Valentini, F., Servidio, S. & Matthaeus, W. Inhomogeneous kinetic effects related to intermittent magnetic discontinuities. Phys. Rev. E. 86, 066405 (2012).

TenBarge, J. M. & Howes, G. Current sheets and collisionless damping in kinetic plasma turbulence. Astrophys. J. Lett. 771, L27 (2013).

Burch, J., Moore, T., Torbert, R. & Giles, B. Magnetospheric multiscale overview and science objectives. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 5–21 (2016).

Kitamura, N. et al. Direct measurements of two-way wave-particle energy transfer in a collisionless space plasma. Science. 361, 1000–1003 (2018).

Yao, G. & Du, J. Dust surface potential for the dusty plasma with negative ions and with a three-parameter non-maxwell velocity distribution. Europhys. Lett. 132, 40002 (2021).

Vasyliunas, V. M. Low-energy electrons on the day side of the magnetosphere. J. Phys. Res. 73, 7519–7523 (1968).

Pollock, C. et al. Fast plasma investigation for magnetospheric multiscale. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 331–406 (2016).

Hesse, M. et al. Theory and modeling for the magnetospheric multiscale mission. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 577–630 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The Funding for Joint Lab of Applied Plasma Technology (JL06120001H). The Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, has funded this project under grant no. (KEP-PhD: 72-130-1443). Data analysis were [in part] carried out on Cray XC50 at Center for Computational Astrophysics, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. Numerical computations were (in part) carried out on Cray XC50 at Center for Computational Astrophysics, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. A. Abid* and M. S. Hussain* contributed equally to this work.A. A. Abid and M. S. Hussain identified the event and implemented the formal analysis, conceptualization, investigation, methodology, visualization, software, validation, and writing—original draft by making comparison to the established theory. Amin Esmaeili and Abdullah Khan contributed to data curation, conceptualization, investigation, writing— review & editing. S. Ali and Yas Al- Hadeethi edited the manuscript, conceptualization, methodology and improved its theoretical part. M. Alharbi and Nada M. Bedaiwi writing— review & editing, conceptualization, validation and improved the quality of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abid, A.A., Hussain, M.S., Esmaeili, A. et al. Analyzing AZ-non-Maxwellian distributions in Earth’s magnetosphere: MMS observations. Sci Rep 14, 29468 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74965-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74965-6