Abstract

Green consumption is a crucial pathway towards achieving global sustainability goals. Product-oriented green advertisements can effectively stimulate consumers’ latent needs and convert them into eventual purchasing intentions and behaviors, thereby promoting green consumption. Given that neuromarketing methods facilitate the understanding of consumers’ decision-making processes, this study combines prospect theory and need fulfillment theory, employing event-related potentials (ERPs) as measures to explore changes in consumers’ cognitive resources and emotional arousal levels when confronted with green products and advertising information. This enables inference regarding consumers’ acceptance of purchasing and their psychological processes. Behavioral results indicated that message framing influences consumers’ purchases, with consumers consuming more green in response to negatively framed advertisements. EEG results indicated that matching positive framing with utilitarian green products was effective in increasing consumers’ cognitive attention in the early cognitive stage. In the late stage of cognition negative frames stimulated consumers’ mood swings more, and the influence of product type depended on the role of message frames, and the consumption motivation induced by the product, whose influence was overridden by external evaluations such as message frames. These research findings provide an explanation for the impact of frame information on consumers’ purchasing decisions at different stages, assisting marketers in devising diverse promotional strategies based on product characteristics to foster the development and practice of green consumption. This will further embed the concept of green consumption advocated by organizations such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and Greenpeace into the public consciousness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Promoting green consumption serves as a vital pathway towards achieving global sustainable development goals. By guiding consumers to choose green products and services, we can effectively drive the sustainable growth of industries. Encouraging green consumption not only contributes to long-term economic development but also constitutes a necessary measure for protecting the Earth’s environment and building a sustainable future1. As environmentalism increasingly permeates consumer culture, the public’s environmental awareness has significantly heightened, with a growing number of consumers embracing the concept of green consumption. However, the benefits of green consumption often do not directly revert to individual consumers but exert a greater influence on other consumers or society as a whole. Additionally, the higher price premium of green products makes it challenging for consumers to accept them2. Although an increasing number of individuals possess values and attitudes aligned with green consumption, the conversion of such attitudes into corresponding purchasing behaviors remains relatively low. Convincing consumers to adopt sustainable consumption and embrace a healthy lifestyle is a relatively difficult process3. Consequently, researching how to prompt consumers to transition from a green consumption attitude to green purchasing behavior becomes an important current issue.

Previous studies have found that persuasive communication strategies can greatly influence consumers’ transition from a positive attitude towards green consumption to actual purchasing behavior4. One such communication strategy widely employed in green advertising is message framing5,6,7, which effectively assists consumers in making choices, evaluations, and decisions8. In green advertising, positive frame message highlights the environmental benefits associated with purchasing green products. This includes emphasizing the environmental advantages, resource conservation, and sustainability of green products, presenting their value through positive language and imagery9. Positive frame advertisements evoke positive emotions and attitudes in consumers, increasing their identification with and willingness to purchase green products. On the other hand, negative frame message accentuates the potential environmental harm associated with not purchasing green products. It may shed light on the environmental damage and excessive resource consumption caused by conventional products, thereby stimulating consumers’ attention and concern, and subsequently enhancing their demand for and willingness to purchase green products10.Message framing biases are associated with attention mechanisms11, and discrepancies exist in the processing intricacies. When detailed processing is not heavily emphasized, positive-framed message may possess greater persuasiveness, whereas the opposite holds true when detailed processing is emphasized12. Negative framing exhibits its most persuasive effect in self-referencing appeals6. Banks (1995) posits that, in cases where consumers perceive message as more credible and important, negative framing may exert a stronger influence compared to positive framing13. White (2011) argued that loss- (gain-) framed messages pairings activate more concrete (abstract) thinking stereotypes, thus improving processing fluency14. Nabi (2019) found that loss- (gain-) framed messages can elicit positive and negative emotions15, and emotions can facilitate the connection between advertising message framing and attitude or behavioral effects16. Arie (2011) found that gain-framed message was more persuasive than loss-framed message, but only when the message was personalized to increase self-relevance5. Research on green product promotion has revealed that negative framing is more effective than positive framing10. Currently, scholars have also employed neuro-marketing methods to investigate framing effects. Yang (2015), employing eye-tracking techniques, found that message framing does not have a moderating effect on purchase intention17. Zubair et al. (2020), utilizing event-related potential techniques, discovered that purchase preferences under positive framing surpass those under negative and neutral framing18.

Some scholars argue that negative framing is more effective in green communication10, while others contend that positive framing is more effective18. The conflicting results from previous research are likely due to the fact that earlier studies focused solely on consumers’ perceptions and evaluations of message framing, overlooking the significant influence of the attributes of green products themselves on consumers’ purchasing decisions in real-life situations19. In green consumption, it is not possible to simply judge which message framing is superior, but rather to consider the combined effects of multiple factors, such as message framing, product type, brand image, price, and consumers’ personal values. Furthermore, although previous research has underscored the importance of message framing in promoting green consumption, there has been insufficient attention to the micro-level aspect of consumers’ cognitive processing of different frames, making it challenging to explain the micro-level psychological processes through which message framing influences purchase decisions. In fact, most consumer behavior decisions occur unconsciously20. Dual-process theory posits that cognitive processes can be categorized into two types: System 1, which is an unconscious and automatic process, and System 2, which is a conscious and controlled process21. Previous message framing research has primarily focused on the perspective of conscious control, often neglecting consumers’ automatic and unconscious processing.

To address the aforementioned practical and theoretical considerations, this study integrates prospect theory and need fulfillment theory to examine how message framing and product types jointly influence consumers’ purchase decisions in the context of green consumption. Prospect Theory posits that individuals’ attitudes towards potential losses and gains are asymmetrical during the decision-making process22. Specifically, individuals are more sensitive to potential losses than potential gains, a phenomenon known as “loss aversion.” Message framing can influence people’s perceptions and evaluations of message outcomes and consequently affect their choices and decisions. Setting positive or negative message frames can yield positive or negative effects9. Prospect Theory emphasizes individuals’ cognitive evaluation of the consequences and outcomes of external choices. However, in the actual process of consumption, consumers’ intrinsic needs and motivations are also crucial. Need Fulfillment Theory asserts that individuals’ behaviors are driven by the pursuit of fulfilling various needs. It emphasizes the impact of individuals’ needs on purchasing and usage behavior and posits that satisfying these needs is the driving force behind individual behavior23. In other words, during the process of purchase and usage, consumers choose products that are perceived to most effectively satisfy their needs. Hedonic and utilitarian products differ in the benefits and functions they provide, which correspond to different intrinsic needs and motivations of consumers. Hedonic products are typically associated with individuals’ emotional needs and self-fulfillment. These products can provide pleasurable experiences, enhance individuals’ emotional states, and fulfill their desires for enjoyment and pleasure24. Consumers’ motivation to purchase and use hedonic products is driven by seeking pleasure, stimulation, entertainment, and emotional satisfaction. Utilitarian products, on the other hand, emphasize functionality and practical use. Consumers’ motivation to purchase and use utilitarian products is more closely linked to practical needs and goal-oriented considerations25. In contrast to hedonic products, utilitarian products represent mostly utilitarian functionalities, where the features of the product are directly and objectively linked to its practicality26. Hence, the difference between utilitarian and hedonic products lies in the disparity between objective and subjective attributes27. Noble’s (2005) study showed that the different functionalities of hedonic and utilitarian products play an important role in consumers’ shopping decision-making process. The connection between the characteristics of utilitarian products and their practicality simplifies the product information, while the subjective nature associated with hedonic products encourages consumers to pursue subjective impressions and reduces reliance on the product itself28. When making decisions about utilitarian products, consumers engage in analytical information processing based on product information29, focusing more on product features and consumer knowledge of the product30. However, when making choices about hedonic products, consumers do not engage in extensive information decision-making processes31. They primarily evaluate the product as a whole, and the final decision involves an emotional process rather than a cognitive one32.Existing research has demonstrated that the attributes of hedonic and utilitarian products have a significant impact on consumers’ purchase decisions in the context of green consumption19.

Current research in green consumption lacks studies combining prospect theory, which emphasizes external choices, with need fulfillment theory, focusing on internal drivers. Furthermore, effective green advertising should consider not only product impacts but also persuasive communication strategies (e.g., message framing) to guide consumers’ environmental values. Therefore, this study explores the combined influence of message framing and product attributes on consumer decision-making from both internal and external perspectives. Previous studies on the relationship between message frames and product types have typically been based on a conscious control perspective. Therefore, this study employs the field of neuromarketing to delve into the micro psychological processes through which these two variables jointly influence purchasing decisions. Neuromarketing is an interdisciplinary field that utilizes neuroscience methods to study consumer behavior. Its aim is to reveal the neural mechanisms underlying consumer decision-making, explore the true motivations driving consumer behavior, and provide support for the development of effective marketing strategies33. Event-related potentials (ERPs), a research tool widely employed in the field of neuromarketing, based on electroencephalogram (EEG) technology, effectively capture underlying emotions and preferences in consumers’ decision-making processes34,35,36.

Participants typically undergo electroencephalography (EEG) recordings while being exposed to different stimuli (e.g., advertising messages or product images), which enables the observation of their brain’s ERP (event-related potential) responses. Event-related potential technology captures the brain’s response to stimuli such as advertisements, brands, or products in a precise and accurate manner, helping to reveal consumers’ cognitive processing and emotional responses to different marketing strategies. By analyzing changes in ERP components (e.g., P2, LPP, etc.), researchers are able to decipher consumers’ attention, emotional responses, and cognitive processing to different product stimuli. The P2 component is believed to be related to consumer attention and therefore can reflect consumers’ attention, interest in marketing stimuli37.The P2 component is the ERP component produced during early cognitive processes, and its intensity is particularly pronounced in the frontal regions of the brain, where the waveform trend is positive and arises around 200ms post-stimulus38. In the domain of neuromarketing research, the study of the P2 component primarily focuses on consumers’ attention bias and attentional capture during purchase decision-making20. Huang et al. (2006) found that negative stimuli elicited higher P2 amplitudes and had shorter latencies compared to positive stimuli, indicating an automatic attention bias39.This phenomenon is also evident in consumer decision-making, where consumers spontaneously alter their attention bias based on the positive and negative valence of stimuli. Generally, negative events require faster action preparation than positive events, thus the negative attentional bias in social environments can ensure consumers’ advantage40. Wang (2020) discovered that satisfying products elicited larger P2 amplitudes compared to dissatisfying products, indicating that consumers allocate more attention to satisfying products during the early stages of consumption41. In our study, since changes in product and message frames affect consumer purchase behavior, we hypothesize that these two factors may cause changes in consumers’ cognitive attention and are explored early by focusing on the P2 component.

In neuromarketing research, LPP (Late Positive Potential) is also a recurring ERP component, which is usually closely related to consumers’ affective responses to advertisements or other marketing stimuli. The LPP component emerges as a positive peak in the ERP waveform between 500 and 800 milliseconds after stimulus onset. It represents one of the late-stage cognitive ERP components and is primarily distributed in the central and parietal regions of the brain. Its role is to elucidate the emotional arousal experienced by consumers and shed light on the deep cognitive processing and cognitive resource allocation during purchase decision-making. This effect is likely associated with the activation of brain regions related to emotions. Research indicates that approximately 500 milliseconds after stimulus onset, pleasant or unpleasant images elicit a positive and enhanced waveform42. Furthermore, the late LPP waveform signifies an increased positivity towards highly arousing stimuli43. Previous studies have shown that the magnitude of the LPP component can reflect the level of emotional arousal evoked by the stimuli, with highly arousing stimuli (such as emotional images or words) eliciting larger LPP amplitudes compared to neutral stimuli44. The LPP is thought to reflect the processing and activation of emotionally relevant stimuli, and thus may well capture changes in the degree of emotional arousal induced by product type and message framing.

From existing research findings, it is evident that the event-related potential (ERP) method has the capability to accurately capture neurophysiological changes in the brain during cognitive processes. This method provides an objective reflection of the neural mechanisms underlying consumer behavior, thereby facilitating a better understanding of the neural processes involved in green consumption and purchase acceptance. The P2 component is predominantly elicited during the early stages of decision-making, representing unconscious perceptual processes and serving as a physiological indicator of attentional resource allocation influenced by stimulus materials. On the other hand, the LPP component is sensitive to motivation-driven emotional arousal and serves as a physiological indicator of emotional processes in the context of green consumer purchasing decisions.

Adjustments in advertising message expression and variations in product types can activate the neural system involved in cognition and emotion. To date, research on green consumption has primarily focused on purchase intentions and behaviors, neglecting the automatic processing aspect. Consequently, this study combines the dual-process theory with the prospect theory and the need fulfillment theory to investigate the psychological conflicts and emotional arousal experienced by consumers when confronted with different types of green products and advertising message expressions, thereby inferring consumers’ unconscious psychological processes. The innovation of this study is the first in-depth examination of the neural mechanisms of message framing and product type on consumers. The objective of this study is to explore how different product types, under different message frames, jointly influence consumers’ cognitive processing and purchase decisions. By assessing consumers’ perceptual differences and cognitive evaluations of message frames and product types, this study aims to investigate purchase decisions in the context of green consumption. On one hand, it can provide a theoretical basis for advertising design of different types of green products by integrating the prospect theory and the need fulfillment theory in the exploration of purchase decisions in green consumption. On the other hand, it can assist marketing practitioners in better predicting consumer behavior, enabling them to select appropriate message framing strategies based on product types and consumers’ psychological characteristics, thereby promoting the development and practice of green consumption and fostering the widespread acceptance of the concept of green consumption advocated by organizations such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and Greenpeace.

Methods

Participants

The ERP experiment involved averaging the EEG data across multiple decision trials from the participants. Previous research has suggested that the optimal number of participants for EEG experiments falls between 19 and 30 individuals45. In our study, we recruited 25 participants (11 males and 14 females) from the subject pool at the Center for Psychology and Behavior at Jianghan University, consisting of undergraduate and graduate students with an average age of 23.44 ± 2.2 years. The college years represent a crucial period for the formation of consumer values, which can significantly influence future purchasing decisions. Three participants with considerable artifacts in their EEG data were excluded, leaving a total of 22 participants (10 males and 12 females) with an average age of 23.37 ± 2.03 years for data analysis. None of the participants reported any neurological or psychiatric disorders. Prior to the experiment, all participants provided written informed consent. This study has obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Jianghan University.

Materials

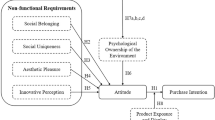

In our study, we selected 60 green products from various high-selling categories as the stimulus materials. These product categories included home appliances, electronic devices, furniture and textiles, and everyday household items. A questionnaire on green product categories was conducted by 24 volunteers who did not participate in the subsequent ERP experiment to screen the experimental materials. The participants rated the utilitarian and hedonic values of the products using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (purely utilitarian) to 7 (purely hedonic). Based on the questionnaire results, the 10 products with the highest scores were designated as hedonic green products (M = 6.996, SD = 5.636), while the 10 products with the lowest scores were designated as utilitarian green products (M = 2.589, SD = 1.789). The stimulus material samples are presented in Fig. 1, with examples of utilitarian green products including biodegradable eco-bags and unbleached toilet paper, and examples of hedonic green products including eco-material pendants and eco-material bracelets. A paired-sample t-test was conducted to compare the average ratings between the two product groups, revealing a significant difference (t = -11.15, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.27). Building upon the selected 20 green products, additional images of the same product category were included to meet the requirements of the ERP experiment in terms of trial repetitions and signal-to-noise ratio. As a result, there were a total of 30 images for each category: 30 for hedonic green products and 30 for utilitarian green products. The content of the advertisements for different frames was developed based on relevant research by Zubair (2020)18. The positive frame advertisement stated, “Purchasing this product contributes to environmental protection,” while the negative frame advertisement stated, “Not purchasing this product hinders environmental protection.” Examples of the experimental stimuli can be found in Fig. 1. All images and information were developed by the authors and evaluated and approved by five experts from the Center for Psychology and Behavior at Jianghan University.

Procedures

The experimental stimuli were presented using the Presentation software developed by Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc. This software is a powerful and programmable application for experimental development and control. The entire experimental procedure consisted of 240 trials. The experiment employed a 2 (product category: hedonic, utilitarian) x 2 (message frame: negative frame, positive frame) within-subjects design. The product category included hedonic green products and utilitarian green products, while the message frame consisted of a positive frame (“purchasing this product benefits the environment”) and a negative frame (“not purchasing this product is detrimental to the environment”). A total of 240 trials were pseudorandomly assigned to four blocks, with each block containing four consecutive trials that did not include all frame conditions for each product. Participants were comfortably seated in a dimly lit and sound-reduced room, positioned 100 centimeters away from the computer screen. Prior to the experiment, participants were briefly introduced to the concept of green products and the environmental benefits of purchasing them, using a priming paradigm to immerse them in the context. Each participant had 10 practice trials to familiarize themselves with the task before the formal experiment. The formal experiment was divided into four blocks, with each block consisting of 60 trials. After completing each block, participants had a 3-minute break before proceeding to the next block. As shown in Fig. 2, during the experiment, after the beginning of each experiment, participants successively viewed the fixation point picture of 1000 ms, product picture of 2000ms, message picture of 2000ms, and finally, the picture of 2000ms was asked to choose whether to accept or not, and the participants judged and selected the key “z” for “acceptable” or the key “x” for “Unacceptable”. In this study, we marked the appearance of the message frame images and record it for subsequent analysis. In this study, when the message frame picture appeared, mark was marked and recorded for subsequent analysis. In addition to this, before the formal experiment, we allow the subjects to practice extensively to ensure that they are familiar with the procedure and to check that they can effectively receive all the experimental information. The formal experiment begins with the subject’s consent.

Data acquisition and analysis

EEG data was recorded using a BrainAmp amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany) and a cap containing 64 Ag/AgCl electrodes, with a sampling rate of 500 Hz. The impedance between the scalp and electrodes at each site was kept below 10kΩ. FCz electrode as reference electrode, and an electrode was placed below the right eye to record vertical eye movements (VEOG). ERPs were analyzed using the BrainVision Analyzer 2.1 (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany). The TP9 and TP10 electrode sites were selected, and the method of two-sided mastoid re-referencing was employed. The signals were then filtered using a third order IIR Butterworth filter with a frequency range from 0.5 to 40 Hz to remove the high-frequency and low-frequency noise. Additionally, a bandpass filter at 49–51 Hz was used to eliminate electrical interference. Following this, each participant’s data was manually inspected for poor electrode channels, which were confirmed by an expert, and replaced accordingly. Considering the assumption of steady-state, the filtered data was segmented into four periods based on the “mark” in the experimental procedure: 200 milliseconds before the beginning of each condition stimulus (pre-stimulus), and 1,000 milliseconds after the stimulus (post-stimulus). By using a stringent automatic suppression program, noise periods were detected with a voltage threshold of (\pm) 100 µV, confirmed by an expert, and excluded from the data. The data was then subjected to Independent Component Analysis (ICA), and manual removal of components with artifacts such as blinks, eye movements, and electromyographic activity was done by an expert. The baseline correction of all epochs was accomplished by subtracting the signal’s average across a 200ms pre-stimulus portion from the entire signal46. After that, the ERP for each condition and region was derived by averaging the epochs for each condition. For the purpose of this study, the P2 and LPP components were chosen. Each individual’s P2 amplitude was calculated by averaging between 190 and 250 milliseconds, and their LPP amplitude by averaging between 600 and 800 milliseconds. These values were then used for statistical analysis.Our hypotheses regarding the P2 and LPP were focused on specific time windows and electrode regions based on prior literature. We did not conduct an exploratory analysis across all time points and electrodes. This a priori selection of regions minimizes the risk of spurious findings associated with multiple comparisons.Therefore, multiple comparison correction was not used in this study.

The P2 component was observed in the frontal and central brain regions. For the analysis, six electrodes (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4) were selected47.Repeated measures ANOVA was performed on the mean voltage values within the time window using 2 (product type: hedonic, utilitarian) x 2 (message frames: negative frames, positive frames) x 6 (electrodes: F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4).The LPP component appeared in the central and parietal brain regions4. For the analysis, nine electrodes (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, P4) were selected. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed on the mean voltage values within the time window using 2 (product type: hedonic, utilitarian) x 2 (message frame: negative frame, positive frame) x 9 (electrodes: F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, P4).

Results

Behavioral results

The participants’ purchase rates under each condition are depicted in Fig. 3. The purchase rate for utilitarian green products in the positive frame condition (M = 0.361, SE = 0.164), hedonic green products in the positive frame condition (M = 0.431, SE = 0.161), utilitarian green products in the negative frame condition (M = 0.601, SE = 0.153), and hedonic green products in the negative frame condition (M = 0.575, SE = 0.164).

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on purchase rates revealed a significant main effect of product type (F(1, 21) = 5.259, p = 0.032, ηp2 = 0.200). Pairwise comparisons showed that the purchase rate for hedonic green products (M = 0.504, SE = 0.005) was significantly higher than that for utilitarian green products (M = 0.481, SE = 0.007). Furthermore, a significant main effect of message frame was found (F(1, 21) = 9.076, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.302), with pairwise comparisons indicating that the purchase rate in the negative frame condition (M = 0.589, SE = 0.032) was significantly higher than that in the positive frame condition (M = 0.396, SE = 0.032). An interaction effect between product type and message frame was also significant (F(1, 21) = 4.571, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.179). Simple effects analysis revealed that under the positive frame condition, participants showed a significantly higher purchase rate for hedonic products (M = 0.431, SE = 0.034) compared to utilitarian products (M = 0.361, SE = 0.035, p = 0.017).

ERPs results

The electrodes Fz in the frontal lobe, Cz in the central lobe, and Pz in the parietal lobe were selected to plot the EEG waveforms in the time window of -200 to 1000 ms (see Fig. 4). The waveform plot shows that the P2 amplitude differs in the 190-250ms time window for the four conditions. To further analyze these differences, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on the grand average P2 amplitudes (190-250ms) across the six electrode sites using the R programming language.

The results showed a significant main effect of electrode (F(5, 17) = 4.274, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.557) on the P2 component. However, the main effects of product type (F(1, 21) = 1.829, p = 0.191, ηp2 = 0.080) and message frame (F(1, 21) = 1.230, p = 0.280 > 0.05, ηp2 = 0.055) were not significant. The interaction effects between electrode and product type (F(5, 17) = 0.439, p = 0.815, ηp2 = 0.114) and electrode and message frame (F(5, 17) = 0.566, p = 0.725, ηp2 = 0.143) were also not significant. However, a significant interaction effect was found between product type and message frame (F(1, 21) = 10.366, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.330).

Subsequently, simple effects analyses were conducted to examine the interaction between message frame and product type. Controlling for the message frame condition, the simple effects analysis revealed that under the positive frame condition, the P2 amplitude (2.254 ± 0.666µV) induced by utilitarian green products was significantly higher than the P2 amplitude (1.456 ± 0.577µV) induced by hedonic green products (p = 0.007). However, under the negative frame condition, there was no significant difference in P2 amplitude between product types. Controlling for the product type condition, the simple effects analysis showed that for hedonic green products, the P2 amplitude (2.148 ± 0.545µV) induced by the negative frame was significantly higher than the P2 amplitude (1.456 ± 0.577µV) induced by the positive frame (p = 0.003). However, for utilitarian green products, there was no significant difference in P2 amplitude between message frames.

The waveform plot shows that the LPP amplitude differs in the 600-800ms time window for the four conditions. To further analyze the amplitude differences among the four conditions, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted in R language on the grand average LPP amplitudes (600-800ms) of the nine electrode sites. The main effect of electrode was significant (F(8, 14) = 6.800, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.795), indicating differential activation across electrode sites. The main effect of product type was not significant (F(1, 21) = 0.392, p = 0.538, η2p = 0.018), suggesting no significant differences between hedonic green products and utilitarian green products. The main effect of message frame was significant (F(1, 21) = 7.178, p = 0.014, η2p = 0.255), indicating a significant effect of positive and negative frames. The LPP amplitude (0.847 ± 0.323µV) induced by the negative frame was significantly higher than the LPP amplitude (0.339 ± 0.280µV) induced by the positive frame (p = 0.014). The interaction effect between electrode and product type was not significant (F(8, 14) = 1.573, p = 0.215, ηp2 = 0.473), and the interaction effect between electrode and message frame was marginally significant (F(8, 14) = 2.519, p = 0.063 < 0.1, ηp2 = 0.590). The interaction effect between product type and message frame was not significant (F(1, 21) = 0.373, p = 0.548, ηp2 = 0.017). Since the main effect of electrode was significant, further analysis was conducted to examine the differences in LPP activation across brain regions. The average LPP amplitudes of the F3, Fz, and F4 electrodes were combined to represent the frontal region, the C3, Cz, and C4 electrodes were combined to represent the central region, and the P3, Pz, and P4 electrodes were combined to represent the parietal region. Subsequently, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on the LPP amplitudes of these three brain regions. The main effect of brain region was significant (F(2, 20) = 10.259, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.506). The LPP amplitude (1.097 ± 0.283µV) in the parietal region was significantly higher than the LPP amplitude in the central region (0.691 ± 0.295µV, p = 0.014) and the frontal region (-0.009 ± 0.343µV, p < 0.001). Additionally, the LPP amplitude in the central region (0.691 ± 0.295µV) was significantly higher than the frontal region (-0.009 ± 0.343µV, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The current study revealed a significant interactive effect of product type and message frame on the P2 component. Based on the Dual-Process Theory, the P2 component reflects cognitive processes in the early stages, and is considered an ERP component that reflects attention allocation and selection. The P2 component induced by positive frame after utilitarian green products is significantly higher than that induced by positive frame after hedonic green products, while the P2 component induced by negative frame has no significant difference between different products.

Different types of green products are associated with distinct consumer motivations. According to the need fulfillment theory, hedonic green products are more in line with the emotional and hedonic consumption motivation, causing hedonic attitudes48. Utilitarian green products are more in line with functional and rational consumption motives, causing a functional attitude49, and have clear environmental protection functions and advantages. After the positive framing of utilitarian green products, consumers may pay more attention to the content in this message framing and attract more consumers’ attention50, thus triggering a stronger P2 response. For the negative message frame, it may cause the consumer’s defense, avoidance and other negative reactions, so different types of products in this case, P2 components may not be significantly different. Previous research has found that during the early cognitive stage, consumers tend to generate pleasant and approach-oriented emotional associations with hedonic green products, leading to the automatic allocation of more attentional resources and greater involvement. The P2 component elicited by hedonic green products is significantly higher than that elicited by utilitarian green products19.However, the above study did not consider the influence of message framing.

In addition, P2 components induced by negative frame were significantly higher than those induced by positive frame after hedonic green products. There was no significant difference in P2 components induced by message framing after utilitarian green products. This may be attributed to the fact that the negative frame elicits negative emotions and increases consumers’ focus on risks and uncertainties, leading them to exert greater cognitive effort when evaluating and choosing utilitarian green products51. Furthermore, according to the need fulfillment theory, hedonic green products align more with consumers’ emotional motivations and experiential needs52. While functional attributes are often cited as primary decision drivers, consumer choices are frequently influenced by a complex interplay of both functional and hedonic attributes. Consumers may rationalize hedonic choices by emphasizing functional justifications, so choosing products based solely on hedonic attributes may cause stronger feelings of guilt and anxiety53. Additionally, negative-framed advertising increases consumers’ sense of uncertainty and risk perception, and also triggers consumer anxiety4. On the other hand, utilitarian green products are perceived as more utilitarian and functional, which mitigates and offsets the risk perception and potential anxiety induced by negative-framed advertising, making utilitarian green products more easily accepted by consumers49. Therefore, positive frames are more suitable for promoting utilitarian green products as they generate higher consumer willingness to choose such products. Conversely, negative frames are more suitable for promoting hedonic green products, as they elicit higher tendencies for risk avoidance. In the marketing of green products, companies can select appropriate message frame advertising strategies based on the product type and consumers’ psychological characteristics. For instance, for utilitarian green products, marketers can use positive-framed advertising to emphasize their positive environmental effects and economic benefits, thus increasing consumers’ attention to the products. On the other hand, for hedonic green products, marketers can highlight their environmental significance and potential personal and social losses under negative-framed advertising, thereby increasing consumers’ purchase intention.

Based on dual-process theory, the LPP component that emerges in the later stages of cognitive processing is closely associated with evaluative and categorization processes. Research in neuromarketing has shown that the LPP component is linked to the cognitive processes involved in evaluative categorization during purchase decisions, specifically in the later stages of cognitive processing prior to making a purchase decision54,55. Simultaneously, the LPP component is closely related to emotional arousal and is sensitive to motivational emotions, thus reflecting consumers’ underlying motivations56,57.

The LPP components in our study showed a significant effect of electrodes on LPP components in the later stages of cognitive processing, suggesting differences in LPP components measured by electrodes in different brain regions. This is because the LPP component undergoes temporal changes during the electroencephalogram process, and different brain regions exhibit varying levels of activation44. Therefore, in our study, multiple electrodes were analyzed to obtain comprehensive and accurate results. The study revealed that different brain regions exhibited different levels of activation and contributions to the LPP component. The parietal region showed the highest level of activation and the most significant contribution to the LPP component, followed by the central region, and the frontal region exhibited the weakest contribution. This confirms that the LPP component dynamically changes with the deepening of consumers’ emotional experiences, and different brain regions are involved in different stages of emotional experience58. The parietal region is closely associated with consumers’ emotional experiences and pleasure sensations59. This demonstrates that the context and content of the study effectively elicit consumers’ emotional responses and experiences. In our study, the central and frontal regions also participated in consumers’ emotional experience processes, although to a lesser extent than the parietal region. The central region is related to consumers’ self-awareness and self-referencing60, while the frontal region is associated with consumers’ cognitive control and decision-making60. Therefore, in the later stages of emotional experience, consumers’ self-awareness and decision-making processes also come into play. The significant differences in LPP among the three brain regions indicate that consumers’ emotional experiences are dynamic processes that involve initial emotional arousal and subsequent self-regulation, and different brain regions play different roles at different stages61. This provides important insights for studying the process and mechanisms of consumers’ emotional changes, and suggests that researchers should pay attention to the relative contributions of different brain regions during different stages of emotional experience to obtain more in-depth conclusions.

The main effect of message framing was significant, with the LPP component elicited by the negative frame significantly higher than that elicited by the positive frame. This finding suggests that in the late cognitive stage, the negative frame can evoke a higher LPP component, indicating a deeper emotional experience in consumers. The negative frame contains greater uncertainty and risk, thus more effectively stimulating emotional fluctuations in consumers. The LPP component primarily reflects the intensity of emotional experience and affective changes61, and a higher LPP indicates a stronger emotional response in consumers. Therefore, this study reveals that the LPP under the influence of negative frame advertising is higher, indicating a deeper level of emotional experience and greater emotional changes in consumers. The promotion of green products relies not only on consumers’ cognitive awareness but also on their emotional experience. Thus, the negative frame can elicit a deeper emotional experience, which is valuable for promoting green consumption decisions. Furthermore, this result aligns with previous research by Maheswaran (1990) and others, suggesting that negative frame information may be more persuasive during the late cognitive stage when detailed processing is emphasized12. Regarding the LPP component, there was no significant main effect of product type, indicating that the two types of products do not directly influence consumers’ emotional experience. This may be due to the influence of product type depending on the role of message framing. In the late cognitive stage, the impact of product-induced consumer motivation is overshadowed by external evaluations such as message framing, highlighting the importance of advertising in green consumption. Marketing professionals can influence consumers’ emotional changes and drive their green consumption behavior by selecting appropriately designed advertisements with negative frames.

This study has made significant contributions to the theoretical framework of consumer behavior in the field of green consumption. It is the first to integrate prospect theory and need fulfillment theory and apply them to the context of green consumption, confirming the roles of message framing and product type in consumers’ green consumption decisions. It provides support for the application of prospect theory and need fulfillment theory in the domain of green consumption and enriches their application in marketing. Furthermore, this study expands the application of neuromarketing methods in the marketing field, particularly in understanding consumers’ green consumption decisions. By employing neuroscience methods, the research reveals the neural mechanisms underlying consumers’ green consumption decision-making processes, thus providing important insights for related studies.

The findings of this study can assist businesses in their marketing of green products by selecting appropriate message framing strategies based on product type and consumer psychological characteristics. For instance, for utilitarian green products, companies can emphasize their positive environmental effects and economic benefits to increase consumer attention. On the other hand, for hedonic green products, companies can highlight the environmental significance under negative framing and the potential personal and societal losses to enhance consumer purchase intention. When formulating green consumption policies and promotional measures, governments can adjust their message framing strategies based on the results of this study. Utilizing negative message framing in promotions can increase consumer attention and cognitive engagement, thus enhancing public persuasiveness. When faced with green product advertisements or purchasing decisions, consumers should focus on the actual effectiveness and environmental value of the products, rather than solely relying on message framing. In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights for governments, businesses, and consumers in the promotion and purchase of green products.

We must acknowledge that this study has some limitations. Firstly, we only investigated hedonic and utilitarian green products, while the types of green products can be further categorized from different perspectives, such as egoistic green products and altruistic green products. Additionally, we did not explore the distinction between green and non-green product types. Therefore, future research should expand the range of product types. Secondly, our study was conducted in mainland China, and it is necessary to consider cultural differences and variations in product preferences among consumers in different regions. Thus, future research should include participants from diverse regions to explore the neural mechanisms of green consumption decision-making among different populations. Lastly, we employed event-related potential (ERP) research methodology, and participants’ performance in experimental conditions may differ from real-life scenarios. Future research could integrate various research methods to enhance external validity and provide more comprehensive insights into promoting green consumption.

Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the influence of green product types and message frame advertising on consumer purchasing decisions and their neural basis. In terms of behavioral outcomes, negative frames were found to capture more attention and interest from consumers. Compared to positive frames, consumers were more inclined to choose green products under negative frames to reduce or avoid the negative environmental impacts. Regarding the neuroelectric results, the matching between positive frames and utilitarian green products effectively increased consumers’ attention distribution in the early stage of cognition. On the other hand, under negative frame advertising, hedonic products garnered attention due to their focus on emotional experiences and the guilt-induced emotions they evoked. Negative frames were also more likely to induce psychological discomfort, which triggered attention towards hedonic green products. In the late stage of cognition, consumers’ emotional experiences constitute a dynamic process, ranging from initial emotional arousal to subsequent self-regulation. Different brain regions play different roles during different stages. The higher LPP component induced by negative frames indicates a deeper emotional experience among consumers. Negative frames encompass greater uncertainty and risk, which effectively stimulate consumers’ emotional fluctuations. Furthermore, the influence of product types depends on the role of message frames. In the late stage of cognition, the impact of consumers’ consumption motives, triggered by products, is covered by external evaluations such as message frames, underscoring the importance of advertising in green consumption.

Data availability

Data available on request due to restrictions e.g. privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zhao, G. et al. Mapping the knowledge of green consumption: a meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 44937–44950 (2020).

Defeng Yang, Yue Lu, Wenting Zhu, & Chenting Su. Going green: how different advertising appeals impact green consumption behavior. J. Bus. Res. 68, 2663–2675 (2015).

McGuire, L. & Beattie, G. Talking green and acting green are two different things: An experimental investigation of the relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes and low carbon consumer choice. Semiotica2019, 99–125 (2019).

Zubair, M. et al. Message framing and self-conscious emotions help to understand pro-environment consumer purchase intention: an ERP study. Sci. Rep. 10, 18304 (2020).

Arie, D., Alexander, R. & Suzanne, P. The persuasive effects of framing messages on fruit and vegetable consumption according to regulatory focus theory. Psychol. Health 26(8), 1036–1048.(2011).

Peggy Sue Loroz. The interaction of message frames and reference points in prosocial persuasive appeals. Psychol. Mark. (2007).

Ceren Ekebas Turedi, Elika Kordrostami, Ilgım Dara Benoit. The impact of message framing and perceived consumer effectiveness on green ads. J. Consum. Mark. (2021).

Montgomery, C. & Stone, G. Revisiting Consumer Environmental responsibility: a five nation cross-cultural analysis and comparison of consumer ecological opinions and behaviors. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. (2009).

Tsai, S.-P. Message framing strategy for Brand Communication. J. Advert. Res. 47, 364–377 (2007).

Olsen, M. C., Slotegraaf, R. J. & Chandukala, S. R. Green Claims and Message frames: how Green New products Change brand attitude. J. Mark. 78, 119–137 (2014).

Hamutal Kreiner, Eyal Gamliel. The role of attention in Attribute Framing. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. (2018).

Maheswaran, D. & Meyers-Levy, J. The influence of message framing and issue involvement. J. Mark. Res. 27, 361–367 (1990).

Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. (1995).

Katherine White, Rhiannon Macdonnell, Darren W. Dahl. It’s the mind-set that matters: the role of Construal Level and Message Framing in Influencing Consumer Efficacy and Conservation behaviors. J. Mark. Res. (2011).

Robin L. Nabi, Nathan Walter, Neekaan Oshidary, Camille G. Endacott, Jessica Love-Nichols, Z. J. Lew, Alex Aune. Can emotions capture the elusive gain-loss framing Effect? A Meta-analysis. Commun. Res. (2020).

Helena Bilandzic, Anja Kalch, Jens Soentgen. Effects of goal framing and emotions on perceived threat and willingness to sacrifice for Climate Change. Sci. Commun. (2017).

Shu-Fei Yang. An eye-tracking study of the Elaboration Likelihood Model in online shopping. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. (2015).

Zubair, M., Wang, X., Iqbal, S., Awais, M. & Wang, R. Attentional and emotional brain response to message framing in context of green marketing. Heliyon 6, e04912 (2020).

Qiang Wei et al. Influence of utilitarian and hedonic attributes on willingness to Pay Green product premiums and neural mechanisms in China: an ERP Study. Sustainability 15, 2403 (2023).

Ozkara, B. Y. & Bagozzi, R. The use of event related potentials brain methods in the study of conscious and unconscious consumer decision making processes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 58, 102202 (2021).

Brakel, L. A. W. & Shevrin, H. Freud’s dual process theory and the place of the a-rational. Behav. Brain Sci. 26, 527–528 (2003).

Harrington, N. G. & Kerr, A. M. Rethinking risk: Prospect Theory Application in Health Message Framing Research. Health Commun. 32, 131–141 (2017).

Pincus, J. D. Well-being as need fulfillment: implications for theory, methods, and practice. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-023-09758-z (2023).

Mcknight, P. & Sechrest, L. The use and misuse of the term ‘experience’ in contemporary psychology: a reanalysis of the experience–performance relationship. Philos. Psychol. 16, 431–460 (2003).

Michal, S. & Myers, J. G. Donations to Charity as Purchase incentives: how well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 24, 434–446 (1998).

Labarge, M. C. et al. Competitive Paper Session: Hedonic Consumption. Adv. Consum. Res. 31, págs. 316–328 (2004).

Verhagen, T., Boter, J. & Adelaar, T. The effect of product type on consumer preferences for website content elements: an empirical study. J. Comput. Commun. 16, 139–170 (2010).

Noble, S. M., Griffith, D. A. & Weinberger, M. G. Consumer derived utilitarian value and channel utilization in a multi-channel retail context. J. Bus. Res. 58, 1643–1651 (2005).

Bridges, E. & Florsheim, R. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: the online experience. J. Bus. Res. 61, 309–314 (2008).

Park, C. & Moon, B. J. The relationship between product involvement and product knowledge: moderating roles of product type and product knowledge type. Psychol. Amp Mark. 20, 977–997 (2010).

Kapferer, J. N. & Laurent, G. Consumer’S involvement Profile: new empirical results. Adv. Consum. Res. 12, 290–295 (1985).

To, P. L., Liao, C. & Lin, T. H. Shopping motivations on internet: a study based on utilitarian and hedonic value. Technovation 27, 774–787 (2007).

Morin, C. Neuromarketing: The New Science of Consumer Behavior. Society 48, 131–135 (2011).

Yoon, E. Y., Humphreys, G. W., Kumar, S. & Rotshtein, P. The neural selection and integration of actions and objects: an fMRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 2268–2279 (2012).

Smidts, A. et al. Advancing consumer neuroscience. Mark. Lett. 25, 257–267 (2014).

Camerer, C. & Yoon, C. Introduction to the Journal of Marketing Research Special Issue on Neuroscience and Marketing. J. Mark. Res. 52, 423–426 (2015).

Wei, Q. et al. The influence of Tourist attraction type on product price perception and neural mechanism in Tourism Consumption: an ERP Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 3787–3803 (2023).

Shang, Q., Jin, J., Pei, G., Wang, C. & Qiu, J. Low-order webpage layout in Online Shopping facilitates Purchase decisions: evidence from event-related potentials. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 29–39 (2020).

Huang, Y.-X. & Luo, Y.-J. Temporal course of emotional negativity bias: An ERP study. Neurosci. Lett. 398, 91–96 (2006).

Carretié, L., Mercado, F., Tapia, M. & Hinojosa, J. A. Emotion, attention, and the ‘negativity bias’, studied through event-related potentials. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 41, 75–85 (2001)

Wang, C., Fu, W., Jin, J., Shang, Q. & Zhang, X. Differential effects of Monetary and Social rewards on product online rating decisions in E-Commerce in China. Front. Psychol. 11, 1440 (2020).

Lifshitz, K. THE AVERAGED EVOKED CORTICAL RESPONSE TO COMPLEX VISUAL STIMULI. Psychophysiology 3, 55–68 (2010).

Cuthbert, B. N., Schupp, H. T., Bradley, M. M., Birbaumer, N. & Lang, P. J. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. Biol. Psychol. 52, 95–111 (2000).

Psychophysiology 57, (2020).

Shi, J., Guo, J. & Fung, R. Y. K. decision support system for purchasing management of seasonal products: a capital-constrained retailer perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 80, 171–182 (2017).

Dini, H., Simonetti, A., Bigne, E. & Bruni, L. E. EEG theta and N400 responses to congruent versus incongruent brand logos. Sci. Rep. 12, 4490 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. The processing of perceptual similarity with different features or spatial relations as revealed by P2/P300 amplitude. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 95, 379–387 (2015).

Lyons, S. J. & Wien, A. H. Evoking premiumness: how color-product congruency influences premium evaluations. Food Qual. Prefer. 64, 103–110 (2018).

Palazon, M. & Delgado-Ballester, E. The role of product-Premium Fit in determining the effectiveness of hedonic and utilitarian premiums: PRODUCT-PREMIUM FIT IN HEDONIC AND UTILITARIAN PREMIUMS. Psychol. Mark. 30, 985–995 (2013).

Ding, Z. et al. Factors affecting low-carbon consumption behavior of urban residents: a comprehensive review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 132, 3–15 (2018).

Saygılı, M. & Yalçıntekin, T. The effect of hedonic value, utilitarian value, and customer satisfaction in predicting repurchase intention and willingness to pay a price premium for smartwatch brands. Management 26, 179–195 (2021).

Okada, E. M. Justification effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. J. Mark. Res. 42, 43–53 (2005).

Chitturi, R., Raghunathan, R. & Mahajan, V. Form versus function: how the intensities of specific emotions evoked in functional versus Hedonic Trade-Offs Mediate Product preferences. J. Mark. Res. 44, 702–714 (2007).

Neurosci. Res. (2017).

Electron. Commer. Res. (2016).

Yen, N.-S., Chen, K.-H. & Liu, E. H. Emotional modulation of the late positive potential (LPP) generalizes to Chinese individuals. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 75, 319–325 (2010).

van Hooff, J. C., Crawford, H. & van Vugt, M. The wandering mind of men: ERP evidence for gender differences in attention bias towards attractive opposite sex faces. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 6, 477–485 (2011).

Fu, H. et al. Don’t trick me: an event-related potentials investigation of how price deception decreases consumer purchase intention. Neurosci. Lett. 713, 134522 (2019).

Blood, A. J. & Zatorre, R. J. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 11818–11823 (2001).

Koechlin, E., Ody, C. & Kouneiher, F. The Architecture of Cognitive Control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science 302, 1181–1185 (2003).

Liu, Y., Huang, H., McGinnis-Deweese, M., Keil, A. & Ding, M. Neural substrate of the late positive potential in emotional Processing. J. Neurosci. 32, 14563–14572 (2012).

Funding

This study was funded by the Hubei University Teaching Research Project (Grant No. 2021290) and the Hubei Provincial Education Department Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (Grant No. 21G078) and Jianghan University Graduate Student Research and Innovation Fund Project (Grant No. KYCXJJ202331).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. and D.L. designed the experiment. D.L., A.B., Y.C., and S.L. prepared the experiment and collected behavioral and ERP data. D.L., J.Z. and S.C. processed and analyzed data. Q.W. and D.L wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of Jianghan University (JY202303 2023.3.15).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Q., Bao, A., Lv, D. et al. The influence of message frame and product type on green consumer purchase decisions : an ERPs study. Sci Rep 14, 23232 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75056-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75056-2

This article is cited by

-

Research on the influencing factors of consumption behavior of agricultural organic waste derivatives

Scientific Reports (2025)