Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is expected to help enterprises reduce costs and improve efficiency, but it may also threaten the employment of employees. It may form a substitution effect on employees’ jobs and might make them experience negative work emotions. Employees’ work emotions could then affect their innovative abilities, which in turn impacts the innovation ability and competitiveness of enterprises. Therefore, the impact of applying artificial intelligence technology on employees’ work well-being has become a pressing issue for businesses today. Through empirical analysis of 349 questionnaire responses, we found that employees’ STARA awareness negatively predicts their work affective well-being. Job stress mediates the relationship between STARA awareness and employees’ work affective well-being. Psychological resilience moderates the relationship between STARA awareness and job stress, moderates the indirect effect of STARA awareness on employees’ work affective well-being through job stress. Theoretical discussions and analyses of the mechanism through which STARA awareness affects employees’ work affective well-being were conducted based on the Conservation of Resources theory. In practice, we provide valuable insights for employees and enterprises to address the impact of AI, enhance work affective well-being, and strengthen enterprises’ innovation and competitiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the vigorous development of digital technology, the total digital economy of five major countries in the world, including the United States, China, Germany, Japan and South Korea, was $31trillion in 2022, accounting for 58% of GDP1. Digital technology is a combination of community, mobile, analysis, cloud, and Internet of Things technologies. Specific application forms include not only traditional information and communication technologies, but also new-generation technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, Internet of Things, and virtual reality2. ChatGPT was born in 2022, pushing artificial intelligence in digital technology to the forefront. Tang has defined that artificial intelligence refers to programs or machines that can autonomously learn, reason, solve problems, and make decisions3. McKinsey’s 2019 Global AI Survey report shows that 58% of respondents said that at least one business process or product service in their organization has artificial intelligence embedded in it4. At present, scholars have formed two views on the impact of the application of artificial intelligence on employee occupations. First, it may bring about a creative effect. Generally speaking, the use of automated mechanical equipment can help enterprises optimize production processes, improve production efficiency and product quality5, expand the scale of production and increase jobs or expand original jobs, thereby increasing labor demand6. Second, it may form a substitution effect. AI technology will have an impact on some job positions. Many positions are at high risk of being replaced by smart devices7. The application of artificial intelligence in the workplace can replace employees in many mechanical and repetitive tasks. It can help employees save time and energy to focus on innovative work8. At the same time, it can replace employees in some high-risk positions to protect their personal health and life safety9.

Whether AI technology is possible to bring substitution effect or creation effect, it is undeniable that the application of AI will have a profound impact on many employees’ employment positions, work forms and work content. Many studies have shown that technological or organizational changes will increase employees’ original workloads10 and impose new job skill requirements on employees11, thereby negatively affecting employee mood and even leading to negative emotions such as depression12. AI continues to optimize and develop, and its performance is increasingly excellent in reducing costs and increasing efficiency for enterprises, empowering innovation, improving services, and creating profits so that more and more enterprises are using AI technology. When employees perceive that AI technology poses a high threat to their career development, it will trigger their negative work emotional reactions13, which is likely to reduce employees’ work well-being.

Research theory and research hypotheses

Work affective well-being is categorized into psychological well-being, integrative well-being, and subjective well-being. Subjective well-being, grounded in the theory of happiness, refers to individuals’ cognitive evaluations and emotional experiences of life, emphasizing their subjective feelings of happiness14. Employee work affective well-being belongs to subjective happiness, reflecting people’s emotional responses to ongoing work events. Individuals who experience more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions are more likely to perceive themselves as happy during work15. Previous studies have shown a significant positive correlation between employee emotional management and organizational innovation performance16. The more positive employees’ emotions and the higher their work happiness, the more innovative behaviors they can be stimulated17. The innovation of enterprise employees is the key for enterprises to obtain competitive advantages18, and employees’ emotions directly predict innovative behavior19. The current impact that AI technology may have on corporate employees’ employment skills and career development, and changes in work affective well-being, has become a challenge that many employees and companies cannot ignore.

STARA awareness (Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms ) refers to employees’ perception of the threat posed by the introduction of AI technology into their work environment regarding their career development20. After the concept of STARA awareness was proposed, more and more scholars began to study the impact of AI technology on employee vocation, mainly focusing on its influence on employee behavior and psychology. The positive effects on employee behavior include employees making challenging evaluations, thereby increasing their participation and organizational commitment21,and stimulating employees’ career exploration behavior22. The negative effects on employee behavior include increasing employees’ turnover intention and knowledge hiding behavior23, and predicting lower employee change support willingness through organizational self-esteem24. The positive effects on employee psychology include increasing employees’ intrinsic work motivation, while the negative effects include negatively predicting employees’ job satisfaction and increasing their turnover intention23, and inducing employees’ feelings of job insecurity25.

Work affective well-being refers to individuals’ emotional reactions to their work. The more positive the emotional experiences during work, the higher the work affective well-being, whereas more negative emotional experiences lead to lower work affective well-being15. A joint survey by Oracle found that due to the adoption of AI technology by businesses, 51% of employees expressed significant concerns about the consequences such as skills obsolescence and unemployment, leading to negative emotions such as a sense of career threat, psychological anxiety and panic26. Moreover, research has shown that the application of AI technology can positively predict employees’ negative emotions13. After the introduction of AI technology into enterprises, employees in positions with a high risk of being replaced by AI are highly likely to perceive AI as a significant threat to their career development. This perception can lead to anxiety and other negative emotional responses, ultimately reducing the work well-being of these employees.

Enterprises’ adoption of AI technology is likely to increase employees’ job stress24. Job stress refers to employees’ severe discomfort when they are forced to deviate from normal or expected patterns in the workplace27. It is an employee’s response to resource loss in the workplace28. According to the conservation of resources theory, resources can be divided into four categories: material resources, energy resources, condition resources, and individual resources. When individuals face losses in these four categories, they invest new resources to supplement the original ones, resulting in a spiral of resource loss and increased stress29. The " substitution effect” of AI technology adopted by companies continuously impacts employees’ employment opportunities (conditional resources)30, skill knowledge (conditional resources)26, job income (material resources)31, and psychological capital (individual resources)32, causing perceived threats and losses. If employees invest more resources in coping with this situation, it is more likely to increase their job stress. STARA awareness refers to employees’ perception of threats to their job resources. The stronger this perception, the stronger their STARA awareness, the greater their job stress may be. Based on this, we propose H2: STARA awareness positively predicts job stress among employees.

According to the conservation of resources theory, employees facing resource loss and persistent job stress not only respond to the current sources of stress, such as investing more psychological capital (individual resources), time, and energy (energy resources) to handle their work but also remain vigilant about other potential stressors, additional resource losses, or exacerbation of existing resource losses. This increases their mental and physical health risks and further exacerbates job stress thereby reducing work affective well-being33. Job stress can reduce employees’ cognitive abilities, increase employee fatigue, and negatively impact on employees’ work performance and well-being34.When a company adopts AI technology to replace employees in performing certain tasks, it will exacerbate the loss of employees’ career resources, thereby increasing the threat of AI to these job resources. As employees’ STARA awareness increases, their job stress may also further intensify, which in turn is more likely to reduce their work affective well-being. In summary, we propose H2a: Job stress negatively predicts work affective well-being among employees. H2b: Job stress mediates the relationship between perceived STARA awareness and work affective well-being among employees.

The conservation of resources theory suggests that psychological resilience, as an important individual resource, plays a crucial role in the acquisition or loss of other resources. Psychological resilience refers to individuals’ ability to quickly recover or become stronger in the face of adversity and is an important component of positive psychological capital35, which serves as a beneficial resource for managing stress36. Studies have shown that people with lower psychological resilience are more likely to experience depressive and anxious emotions than those with higher psychological resilience, leading to higher job stress. Generally, psychological resilience and job stress are negatively correlated37. Hobfoll pointed out that employees with abundant psychological resilience resources are more capable of resisting stress or crisis38. Individuals with higher psychological resilience, when perceiving the potential career threats posed by AI technology, are more likely to maintain a more confident attitude, and face the potential negative impacts of AI on their work with a more positive and optimistic attitude. They are also better equipped to alleviate negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, reduce job stress, and effectively regulate their work affective well-being. Based on this, we propose H3a: Psychological resilience moderates the positive prediction of STARA awareness on job stress. H3b: Psychological resilience moderates the mediating effect of job stress on the relationship between STARA awareness and work affective well-being.

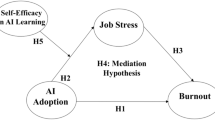

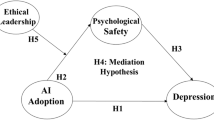

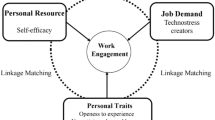

In conclusion, to explore the relationship between STARA awareness and employees’ work affective well- being, as well as the mediating role of job stress and the moderating role of psychological resilience, this study constructs a moderated mediation model for discussion. The aim is to explore the mechanism by which STARA awareness predicts employees’ work affective well-being and to provide practical references for how enterprises should respond to the impact of STARA awareness on employees’ emotions, improve employees’ work affective well-being, stimulate employees’ innovative behavior, and enhance enterprise competitiveness. The specific study model is shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participant

Research suggests that employees in production positions have the strongest STARA awareness in enterprises39. Therefore, this study collected relevant data from employees in the production departments of manufacturing enterprises undergoing digital transformation for our research.

The first author of this study obtained ethical approval from the Academic Committee of Liaoning Technical University, and all research methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. In this study, the employed staff were invited to provide data by filling out questionnaires online, using the professional online survey software “Questionnaire Star” to obtain informed consent and survey data from the participants. All surveys were anonymous, and all employed staff participating in the study did so voluntarily. The link shared with the employed staff included the survey questionnaire and instructions for completing. Upon clicking the link, employed staff were directed to the instructions page, which informed them that their participation in the survey would not have any direct impact on themselves, and that the data collected would be summarized and disclosed comprehensively after processing. Additionally, the page also provided brief information about the survey, including the definition of artificial intelligence used in this article, and lists some specific examples of the application of artificial intelligence technology in the production department of manufacturing companies. At the same time, this part also included confirmation questions about whether the production department of the company where the employee works adopts intelligent technological machines and equipment, and identity confirmation questions about whether the interviewed employee is an employee of the production department of the manufacturing company. If one of the interviewee’s answers is no, the questionnaire will be terminated immediately. If the employees’ answers are ‘yes’, they will enter the informed consent interface that includes their privacy and anonymity rights. Additionally, it informed participating employees that their participation was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. After reading the information, they clicked “I have read and understood the above information and agree to participate in the survey” to express their agreement, and then began to answer the formal questionnaire.

A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, with an initial recovery of 427 questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 94.89%. After screening, 349 valid questionnaires were retained, yielding a final effective response rate of 81.73%. Among the respondents, there were 185 males, accounting for 53.01%, and 164 females, accounting for 46.99%. In terms of age distribution, the main age group ranged from 21 to 49 years old, accounting for 78.80%. Regarding educational background, 13.75% had a junior high school education or below, 69.91% had a high school education or equivalent, and 16.34% had a college degree or above.

Measurement scales

In the measurement scales used in this study, all variables use mature scales from scholars’ research literature. All scales utilize the Likert 5 points scoring method, with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 5 indicating “strongly agree”.

STARA: STARA awareness selected the scale of Brougham and Haar’s study, which consists of 4 items20. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study is 0.849. Typical items include “I think my job may be replaced by artificial intelligence”.

Job Stress: Job stress adopts the scale developed by Lait and Wallace, consisting of 6 items40. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study is 0.888. Typical items include “I feel that work matters are beyond my control”.

Psychological Resilience: Psychological resilience consists of 9 items41, adopts the single-factor scale adapted by Siu et al. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study is 0.907. Typical items include “I can respond positively in very difficult situations” etc.

Work Affective Well-being: Work affective well-being adopts Huang Liang’s scale, consisting of 5 items42. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study is 0.860. Typical items include “My work makes me feel very relaxed”.

Control Variables: In the literature on employees’ work affective well-being, variables such as gender, age, education level, and years of work experience may affect employees’ work affective well-being24 42. Therefore, these variables are set as control variables.

Statistical analysis

This study utilized both SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 28.0 for data analysis. Specifically, AMOS 28.0 was employed for confirmatory factor analysis and testing for common method bias. SPSS 27.0 was used for descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and hierarchical regression analysis. The SPSS PROCESS macro was utilized to examine the mediation and moderation effects.

Results

Discriminant Validity Test and Common Method Bias Test

This study used confirmatory factor analysis to test the discriminant validity among the four main variables. The results of the four-factors model are as follows: χ2 = 300.434, df = 246, CFI = 0.986, TLI = 0.985, IFI = 0.986, SRMR = 0.039, RMSEA = 0.025. This indicates that the fit indices of the four factors are ideal, and the discriminant validity among the variables is satisfactory (as shown in Table 1). To further test the common method bias in this study, the widely used Harman single-factor test method is employed. The results show that the variance explained by the first principal component with an eigenvalue greater than 1 is 27.06%, which is less than 40% (the critical value). Given the limitations of the Harman single-factor test method, such as its lack of sensitivity, Podsakoff ‘s method is also employed43. In this method, an unmeasured common method latent factor is added to the original model to form a new model, and its fit with the original model is compared. As shown in Table 1, the fit indices of the five-factors model with the addition of the method factor (χ2 = 247.286, df = 222, CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.992, IFI = 0.994, SRMR = 0.032, RMSEA = 0.018) are superior to those of the four-factors model, albeit marginally. Overall, this indicates that there is no serious common method bias issue in this study.

Correlation analysis

Figure 2 is the Pearson correlation thermogram that illustrates significant negative correlations between STARA awareness and work affective well-being (r =-0.265, p < 0.01), indicating that a stronger awareness of STARA is associated with lower levels of work affective well-being. There is also a significant positive correlation between STARA awareness and job stress (r = 0.197, p < 0.01), suggesting that a stronger awareness of STARA is associated with higher levels of job stress. Furthermore, there is a significant negative correlation between job stress and work affective well-being (r = -0.190, p < 0.01), indicating that higher job stress is associated with lower levels of work affective well-being. Additionally, psychological resilience is correlated with STARA awareness, job stress, and work affective well-being at a significant level of 0.01 or higher. These results provide preliminary support for the overall hypotheses of this study.

Regression analysis direct effects

This study utilized hierarchical regression analysis to test each hypothesis. M5 and M6 examined the relationship between STARA awareness and work affective well-being. After controlling for variables such as gender, age, work years and education, STARA awareness significantly negatively predicted work affective well-being (β = -0.258, p < 0.001), supporting H1. M1 and M2 tested H2, where STARA awareness significantly positively predicted job stress (β = 0.202, p < 0.001), supporting H2. M7 directly verified that job stress negatively predicted work affective well-being (β = -0.186, p < 0.001), supporting H2a. (see in Table 2)

Mediation analysis

The mediation effect of job stress is demonstrated in M8 of Table 2. The mediation effect value of job stress between STARA awareness and work affective well-being is β= -0.140, p < 0.01, and it was tested using the Bootstrap method with SPSS PROCESS command. M4 was selected in the PROCESS command, with a 95% CI and 5000 bootstrap samples. The indirect effect of job stress in mediating the relationship between STARA awareness and work affective well-being did not include zero (Effect = -0.024, BootSE = 0.014, 95% CI = [-0.0563, -0.0030]), supporting H2b.

Moderation effects

Before examining the moderation effect of psychological resilience, variables were centralized, and interaction terms AI×RE were constructed. Subsequently, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. The results of the hierarchical regression analysis are presented in M3 and M4. (see in Table 2) After controlling for the main effects, the interaction term (STARA×PR) between STARA awareness and psychological resilience significantly influenced job stress (β = -0.194, p < 0.01), indicating that psychological resilience negatively moderates the positive relationship between STARA awareness and job stress. Therefore, hypothesis H3a is supported. To further clarify the moderation effect, a moderation plot was generated as shown in Fig. 3. When psychological resilience is low, the regression slope of job stress with STARA awareness (k = 0.416) is higher compared to when psychological resilience is high (k = 0.028). Thus, psychological resilience weakens the positive prediction of job stress by STARA awareness, and the stronger the psychological resilience, the weaker the positive prediction of job stress by STARA awareness.

Moderated Mediation

Based on the above data results, the mediation effect of job stress between STARA awareness and work affective well-being has been confirmed, and the moderating effect of psychological resilience on job stress has been validated. Therefore, further examination of the moderated mediation effect was conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS, following Hayes44.

When employees have low levels of psychological resilience, the indirect effect of STARA awareness on work affective well-being through job stress is -0.056, with a 95% CI of [-0.1367, -0.0071], indicating a significant mediating effect of job stress. However, when employees have high levels of psychological resilience, the indirect effect of STARA awareness on work affective well-being through job stress is -0.004, with a 95% CI of [-0.0287, 0.0164], showing a non-significant mediating effect of job stress. The difference in the indirect effects under conditions of high and low psychological resilience is 0.053, with a 95% CI difference of [0.0026, 0.1387]. This indicates that there is a significant difference in the mediating effect of job stress on employees’ work affective well-being when psychological resilience is at different levels, thus confirming H3b. (see in Table 3)

Conclusion

Summary of main findings

This study uses 349 samples to conduct an empirical analysis on the relationship between STARA awareness and employees’ work affective well-being, as well as the mediating mechanism of job stress and the moderating role of psychological resilience. Empirical data shows: (1) The STARA awareness negatively predicts employees’ work affective well-being. The stronger the awareness of STARA, the weaker the employees’ work affective well-being. (2) Job stress mediates the relationship between the STARA awareness and employees’ work affective well-being. The stronger the STARA awareness, the greater the job stress of employees, which in turn predicts lower work affective well-being. (3) Psychological resilience toughness negatively regulates the awareness of STARA and job stress. The stronger the psychological resilience, the weaker the positive prediction of STARA awareness on job stress.

Discussion

This study found that STARA awareness significantly and negatively predicts employees’ work affective well-being, meaning the higher the employee’s STARA awareness, the lower their work affective well-being. Due to the high efficiency and convenience of AI technology, more and more companies are using AI technology, which has impacted the employment of employees. Studies have shown that with the development of AI technology, a series of procedural and computational tasks are being replaced by AI, such as formalities, salary accounting45. Some employees are facing a sharp increase in the risk of unemployment, and their sense of occupational threat has also increased. According to the conservation of resources theory, resources are the key elements that employees value and achieve their career development goals. Employees facing the “substitution effect” of AI technology on their careers and the reshaping of their career development environment will be more likely to face an increase in the loss of their own resources and an increase in the perception of threats to their career development caused by artificial intelligence technology, and a sense of career crisis and psychological anxiety will also be more likely to increase20, and the probability of reduced work affective well-being will be higher.

This study reveals the mediating effect of job stress between STARA awareness and work affective well-being. According to the results of our survey data, the stronger the employee’s STARA awareness, the greater their job pressure and the lower their affective well-being at work. According to the theory of resource conservation, when enterprises introduce artificial intelligence technology, employees whose work resources are affected and threatened will have a higher awareness of STARA. At the same time, employees’ emotional resources to cope with job stress and work challenges will be damaged, and job stress will further increase33, employees’ negative emotions further increase, which predicts lower work well-being46. Existing research has shown that when stress levels are high, employees have self-doubt about their ability to complete tasks, reducing employees’ self-efficacy, which negatively predicts work well-being47; In addition, long-term job stress can also make employees feel disgusted with their work, and their affective well-being will weaken48. In summary, the higher the employee’s STARA awareness, job stress and negative emotions may also be positively related to it, and the employee’s work affective well-being may also be lower.

This study clarifies the moderating role of psychological resilience between STARA awareness and job stress. It is discovered by analyzing the data we collect that psychological resilience can weaken the positive prediction of STARA awareness on job stress; the stronger the psychological resilience, the weaker the positive prediction of STARA awareness on employee job stress. The American Psychological Association points out that psychological resilience refers to an individual’s “ability to bounce back” when faced with threats, adversities, tragedies and other life stresses and setbacks. Psychological resilience can give individuals a positive and optimistic attitude49 and a high level of psychological resources can change individuals’ cognitive evaluation of stress50, and has a positive effect in buffering and regulating stress. The higher the psychological resilience of employees, the weaker the positive prediction of their STARA awareness on job stress, and the weaker the negative prediction of job stress on work affective well-being.

Recommendations

The stronger the STARA awareness, the weaker the employees’ work affective well-being. Therefore, enterprises should take measures to reduce employees’ STARA awareness. Enterprises should actively publicize the challenges and opportunities brought by the development of AI technology to employees, clarify the integration links between AI technology and employees’ work, provide employees with a sufficient adaptation environment, and provide employees with opportunities and platforms for learning and utilizing AI technology, help employees establish a correct understanding of AI technology, quickly adapt to the changes in the work environment. For example, BAC.US and Astra Zeneca have used artificial intelligence technology to create virtual work reality scenarios for employees to conduct pre-job training for employees, helping them improve their skills and work efficiency. Walmart employees are learning how to work with cleaning and inventory counting robots and how to manage, operate and integrate these robotic processes into their jobs. These are all examples of using AI to help employees improve their skills. Not only can it increase employees’ awareness of the “instrumentality” and “partnership” of AI, it can also allow employees to understand the convenience and help that AI brings to their work, reduce employees’ STARA awareness, and improve their work affective well-being.

Enterprises should focus on relieving employees’ job stress. The stronger the STARA awareness, the more likely it is to reduce employees work affective well-being through job stress. Therefore, when introducing AI technology, enterprises should pay attention to changes in employees’ psychological status, take appropriate measures to alleviate employees’ negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression in a timely manner. At the same time, according to the conservation of resources theory, when the depletion of resources exceeds the replenishment of resources, it will threaten employees’ physical and mental health. Therefore, enterprises should actively replenish depleted work resources for employees in their daily management, or supplement other beneficial work resources to alleviate their job stress. For example, providing employees with a good environment for skills learning and career planning guidance. In Sweden, most employers make voluntary payments to “Job Boards” (private equity funds designed to help retrain unemployed workers). France has a similar system that requires employers to fund the vocational training system. The above examples show that companies can create a skill learning environment for employees by providing funds, improve work skills, and help employees re-employ.

Enterprises should focus on improving employees’ psychological resilience. This research has shown that high psychological resilience can weaken the positive impact of the STARA awareness on job stress and alleviate the negative impact of job stress on employees’ work affective well-being. Therefore, enterprises should carry out employees’ psychological resilience enhancement plans in their daily management to empower employees. For example, Alibaba provides employees with time management skills, emotional regulation methods and other resources to help them better balance their emotional state during their busy work. Tencent cooperates with a number of professional institutions through cooperation to set up psychological consultation hotline and face-to-face consultation services within the company. They all encourage employees to develop a positive attitude, remain optimistic and confident when facing difficulties and challenges, and enhance employees’ psychological resilience. The psychological resilience of employees has been improved, and employees can more calmly confront the impact of artificial intelligence, so that with the help of the company and their own efforts, they can achieve self-improvement in the AI era.

Limitations and directions of future research

This study has the following limitations and needs further research for improvement. (1) This research only investigated the data of employees in the production department of manufacturing enterprises and did not investigate the data of employees in other positions. Future research could investigate and analyze the employees’ work affective well-being in other companies and in other positions. (2) The sample data selected in this research are all self-evaluations by employees and have not been longitudinally collected. Future research can adopt hetero-evaluation and multi-time-point research methods to collect data to compensate for the survey design flaws in this research. (3) Future research can explore other mediating mechanisms, such as career growth, emotional exhaustion, performance pressure, and job reshaping, in the relationship between STARA awareness and employees’ work affective well-being. (4) This research only reveals that psychological resilience is a boundary condition for the impact of STARA awareness on employees’ work affective well-being. Future research can expand the boundary conditions, such as job autonomy, work vigor, and self-efficacy51.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Harvard Dataverse, DRAFT VERSION with the primary accession https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XDF4JB. In addition, you can also directly send an email to the corresponding author to obtain relevant data.

References

CAICT. Global Digital Economy White Paper. (2023). http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/202401/t20240109_469903.htm, 2024).

Hinterhuber, A., Vescovi, T. & Checchinato, F. Managing Digital Transformation Understanding the Strategic Process 13–66 (Routledge, 2021).

Tang, M. When conscientious employees meet intelligent machines: an integrative approach inspired by complementarity theory and role theory. Acad. Manag. J. 65, 1019–1054 (2022).

Yufei, M. & Wenxin, H. The impact of Artificial Intelligence Applications on Job Quality of Human Resource practitioners. Bus. Manage. J. 42, 92–108 (2020).

Branca, T. A. et al. The challenge of digitalization in the steel sector. Metals. 10, 288 (2020).

Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P. Automation and new tasks: how technology displaces and reinstates labor. J. Economic Perspect. 33, 3–30 (2019).

Frey, C. B. & Osborne, M. A. The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 114, 254–280 (2017).

Verma, S. & Singh, V. Impact of artificial intelligence-enabled job characteristics and perceived substitution crisis on innovative work behavior of employees from high-tech firms. Comput. Hum. Behav. 131, 107215 (2022).

Colla, V. et al. Introduction of symbiotic human-robot-cooperation in the steel sector: an example of social innovation. Matériaux Techniques. 105, 505 (2017).

van Hetty, I., Bakker, A. B. & Euwema, M. C. Explaining employees’ evaluations of organizational change with the job-demands resources model. Career Dev. Int. 14, 594–613 (2009).

Ďurčo, R., Pielesz, M. & Sakařová, D. In Industry 4.0 and the Road to Sustainable Steelmaking in Europe: Recasting the Future 113–127 (Springer, 2024).

Burgard, S. A., Brand, J. E. & House, J. S. Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 777–785 (2009).

Xiaomei, Z., Jingjing, R. & Qin, H. Will the application of Artificial Intelligence Technology trigger employees negative emotions? Based on the perspective of Resource Conservation Theory. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 28, 1285–1288. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.06.042 (2020).

Jianmin, S., Xiufeng, L. & Congcong, L. Concept evolution and measurement of work happiness. Hum. Resource Dev. China. 38–47. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2016.13.005 (2016).

Lin, Q. Measuring Affective Well-being. J. South. China Normal University (Social Sci. Ed.), 5, 137–142 (2011).

Xiuqing, Z. Research on the inhibiting mechanism of Employee Innovation Behavior from the perspective of negative emotion. Contemp. Economic Manage. 42, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.13253/j.cnki.ddjjgl.2020.12.009 (2020).

Shuli, S. & Fei, Z. Research on the impact mechanism of Work Happiness of Knowledge-based employees in the media industry on Innovation Performance. Mod. Communication(Journal Communication Univ. China). 40, 62–68 (2018).

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J. & Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 39, 1154–1184 (1996).

Wenli, Z., Yuandong, G. & Tianzhen, T. Influence of R&D personnel’s positive emotion on their creative behavior: the mediating effect of self-creativity efficacy and job involvement. Sci. Res. Manage. 41, 268–276. https://doi.org/10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2020.08.028 (2020).

Brougham, D. & Haar, J. Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): employees perceptions of our future workplace. J. Manage. Organ. 24, 239–257 (2018).

Ding, L. Employees challenge-hindrance appraisals toward STARA awareness and competitive productivity: a micro-level case. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 33, 2950–2969 (2021).

Presbitero, A. & Teng-Calleja, M. Job attitudes and career behaviors relating to employees’ perceived incorporation of artificial intelligence in the workplace: a career self-management perspective. Personnel Rev. 52, 1169–1187 (2023).

Brougham, D. & Haar, J. Technological disruption and employment: the influence on job insecurity and turnover intentions: a multi-country study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 161, 120276 (2020).

Guanglu, X. & Haotian, W. The Effect of Artificial Intelligence (AI) awareness on employees’ Career satisfaction: the role of job stress and goal orientations. Hum. Resource Dev. China. 40, 15–33. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2023.7.002 (2023).

Lingmont, D. N. & Alexiou, A. The contingent effect of job automating technology awareness on perceived job insecurity: exploring the moderating role of organizational culture. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 161, 120302 (2020).

Autor, D. H. Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. J. Economic Perspect. 29, 3–30 (2015).

Summers, T. P., DeNisi, A. S. & DeCotiis, T. Attitudinal and behavioural consequences of felt job stress and its antecedent factors: a field study using a new measure of felt stress. J. Social Behav. Personality. 4, 503 (1989).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513 (1989).

Hobfoll, S. E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421 (2001).

Li, S. & Zhen, T. How to embrace the advent of the generative AI era? Tsinghua Bus. Rev., 5, 6–15 (2023).

Jie, T., Wenkai, S. & Zhong, Z. Technological Transformation, the employment structure of the Mobile Population, and the Trend of Income polarization. Acad. Res. 3, 80–85 (2021).

Xizhou, T. & Jinyu, X. The influence of POS on Working behaviors of employees: empirical research on mediating role of Psychological Capital. Nankai Bus. Rev. 13, 23–29 (2010).

Han, Y., Chaudhury, T. & Sears, G. J. Does career resilience promote subjective well-being? Mediating effects of career success and work stress. J. Career Dev. 48, 338–353 (2021).

Lamb, S. & Kwok, K. C. A longitudinal investigation of work environment stressors on the performance and wellbeing of office workers. Appl. Ergon. 52, 104–111 (2016).

Den Hartigh, R. J. & Hill, Y. Conceptualizing and measuring psychological resilience: what can we learn from physics? New Ideas Psychol. 66, 100934 (2022).

Xixi, Z., Xinglin, H. & Bingcheng, W. Multiple realization paths of the trickle-down Effect of Leader Resilience. Nankai Bus. Rev. 27, 28–37 (2024).

Xiaojiao, L. Relationship of University teachers Mental Resilience and work stress. Univ. Educ. Sci. 4, 74–79 (2015).

Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C. & Geller, P. Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. J. Social Personal Relationships. 7, 465–478 (1990).

Gunglu, X. & Haotian, W. Research on the influence of Technological disruption awareness on EmployeesIntentions to engage in change-supportive behaviors: with the development of Artificial Intelligence as the background. East. China Economic Manage. 36, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.19629/j.cnki.34-1014/f.210803004 (2022).

Lait, J. & Wallace, J. E. Stress at work: a study of organizational-professional conflict and unmet expectations. Relations Industrielles. 57, 463–490 (2002).

Siu, O. L. et al. A study of resiliency among Chinese health care workers: capacity to cope with workplace stress. J. Res. Pers. 43, 770–776 (2009).

Liang, H. On the Dimensional structure of the employee Occupational Well-being in Chinese enterprises. J. Cent. Univ. Finance Econ. 10, 84–92 (2014).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879 (2003).

Hayes, A. F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 50, 1–22 (2015).

Ni, L. In the AI era, HR’s way of attack. Hum. Resour. 10, 28–30 (2017).

Shanming, Z., Xiaolu, Z., Kuang, L. & Yuanhua, Y. The effect of emotional abuse on College Students’ anxiety: the role of resilience and sense of security. Psychology:Techniques Appl. 10, 695–704. https://doi.org/10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2022.11.006 (2022).

Yi, S., Zhen, Z. W. & Stress Occupational Well-being of managers: the effect of self-efficacy and recovery experiences. Social Sci. Nanjing. 24–30. https://doi.org/10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2016.09.004 (2016).

Zhengang, Z., Wenyue, C., Baosheng, Y. & Yongjin, Y. A study of relationship between Workplace Telepressure and Affective Well-Bing at Work: the role of cognitive efficiency and resilience. Hum. Resource Dev. China. 40, 22–34. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2023.6.002 (2023).

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B. & Norman, S. M. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572 (2007).

Yaqiang, F. & Xuan, W. Relationship between Resil ience, stress cognitive Appraisal, Coping and Mental Heal th of teenage students. China J. Health Psychol. 21, 735–738. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2013.05.025 (2013).

Zhang, Y. & Chen, Y. Research trends and areas of focus on the Chinese Loess Plateau: a bibliometric analysis during 1991–2018. Catena. 194, 104798 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.J. and J.J. designed the research and questionnaire; G.J., J.J., H.L. collected and analyzed the questionnaire data; J.J. wrote and revised the manuscript; H.L. prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3; Tables 1, 2 and 3. The manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, G., Jiang, J. & Liao, H. The work affective well-being under the impact of AI. Sci Rep 14, 25483 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75113-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75113-w

This article is cited by

-

Invulnerability bias in perceptions of artificial intelligence’s future impact on employment

Scientific Reports (2025)