Abstract

Paphiopedilum armeniacum, Paphiopedilum wenshanense and Paphiopedilum emersonii are critically endangered wild orchids. Their populations are under severe threat, with a dramatic decline in the number of their natural distribution sites. Ex situ conservation and artificial breeding are the keys to maintaining the population to ensure the success of ex situ conservation and field return in the future. The habitat characteristics and soil nutrient information of the last remaining wild distribution sites of the three species were studied. ITS high-throughput sequencing was used to reveal the composition and structure of the soil fungal community, analyze its diversity and functional characteristics, and reveal its relationship with soil nutrients. The three species preferred to grow on low-lying, ventilated and shaded declivities with good water drainage. There were significant differences in soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and available phosphorus among the three species. There were 336 fungal species detected in the samples. On average, there were different dominant groups in the soil fungal communities of the three species. The functional groups of soil fungi within their habitats were dominated by saprophytic fungi and ectomycorrhizae, with significant differences in diversity and structure. The co-occurrence network of habitat soil fungi was mainly positive. Soil pH significantly affected soil fungal diversity within their habitats of the three paphiopedilum species. The study confirmed that the dominant groups of soil fungi were significantly correlated with soil nutrients. The three species exhibit comparable habitat inclinations, yet they display substantial variations in the composition, structure, and diversity of soil fungi. The fungal functional group is characterized by a rich presence of saprophytic fungi, a proliferation of ectomycorrhizae, and a modest occurrence of orchid mycorrhizae. The symbiotic interactions among the soil fungi associated with these three species are well-coordinated, enhancing their resilience against challenging environmental conditions. There is a significant correlation between soil environmental factors and the composition of soil fungal communities, with pH emerging as a pivotal factor regulating fungal diversity. Our research into the habitat traits and soil fungal ecosystems of the three wild Paphiopedilum species has established a cornerstone for prospective ex situ conservation measures and the eventual reestablishment of these species in their native landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Orchidaceae is among the largest families of higher plants and is recognized as one of the most morphologically diverse plant families in nature. There are approximately 25,000 to 35,000 species of Orchidaceae distributed across 800 genera worldwide1,2. Orchid organs are highly specialized, diverse, and adaptable to various environments, being widely distributed across different terrestrial ecosystems, with the exception of polar regions and extreme arid deserts3,4. These plants possess specialized mycorrhizal communities and unique pollination mechanisms5, rendering them extremely sensitive to habitat changes6,7. Furthermore, orchids hold significant ornamental value and medicinal properties8, establishing them as “flagship” species within their ecological contexts9. Currently, wild orchids are under significant pressure to survive due to severe anthropogenic activities and the effects of global climate change. All wild orchids worldwide are protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which explicitly prohibits their trade10. The genus Paphiopedilum, belonging to the Orchidaceae family, is characterized by its large, slipper-shaped lips on the petals11,12. The shape of the flower resembles the slippers worn by noble European women during the Middle Ages, which has led to its common name, the slipper orchid. This group represents the most ornamental category within the Orchidaceae family and is highly regarded among international floral enthusiasts. As a result, this topic has attracted the attention of numerous scientific researchers and flower aficionados worldwide13. Due to their ornamental value, the wild populations of Paphiopedilum are vulnerable to predatory mining and the smuggling trade14. This group of plants encounters considerable challenges in reproducing in the wild, resulting in a rapid decline in both species diversity and population numbers, with some species potentially facing extinction15. Currently, all Paphiopedilum species are listed on the CITES List and the IUCN Red List of endangered species. In China, they are also included in the State Key Wild Plant Protection List, underscoring their rarity among globally endangered plant groups16. Southwest China serves as both the origin and differentiation center for Paphiopedilum, as well as a distribution hotspot. However, a recent survey has revealed that wild Paphiopedilum plants in Southwest China are experiencing severe damage, particularly species such as Paphiopedilum armeniacum (P. armeniacum), Paphiopedilum wenshanense (P. wenshanense), and Paphiopedilum emersonii (P. emersonii), which are among the most endangered17. Currently, fewer than ten natural distribution sites for these three Paphiopedilum species have been identified, and their habitats are at significant risk of degradation and loss. These species are classified as having small populations on China’s wild plant protection list, which indicates an imminent risk of extinction in their natural environments. This classification underscores the urgency and priority of conservation efforts.

Understanding the ecological habits of orchids is essential for effective scientific conservation efforts, particularly for the ex situ conservation of endangered species18,19. In their natural environment, orchid seeds are small, and their germ is underdeveloped and nutrient-poor; thus, seed germination relies on the assistance of fungi that provide critical resources such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus20. The entire growth cycle of orchids is contingent upon the presence of compatible mycorrhizal fungi in the soil, whether specialized or generalist. Given the significant dependence of Orchidaceae on mycorrhizal fungi, it can be inferred that their spatial distribution is largely influenced by the distribution of microorganisms in the habitat soil. Consequently, the composition of fungi in the habitat soil emerges as a key characteristic of the ecological habits of Orchidaceae plants21,22. Evidence suggests that alterations in mycorrhizal fungal communities, driven by habitat conditions, can directly or indirectly influence the distribution dynamics of terrestrial orchids21,23. Some introduction experiments indicate that orchid seeds can germinate outside areas where orchids are densely distributed, suggesting that these seeds may recruit fungi from the surrounding soil to establish symbiosis, germinate, and grow24,25. This process may gradually lead to the formation of a microbial community centered around the orchid roots. The varying demands for fungal community composition during different growth stages of orchids can alter the original composition of the fungal community. Therefore, the soil fungal community in the habitat may serve as the source of orchid mycorrhizal fungi, while the growth of orchids may also contribute to changes in the structure of the soil fungal community in their habitat26,27. Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated that areas adjacent to orchid growth are hotspots for fungal spore germination and the establishment of new plants28. However, most current studies have concentrated on the endophytic fungi and rhizosphere fungal communities of orchids, while largely neglecting the fungal communities present in the surrounding soil29,30,31,32. This lack of understanding regarding the sources and processes involved in the construction of orchid mycorrhizal fungal communities hinders the development of simulated environments for ex situ conservation. Currently, the dwindling numbers of remaining wild populations and habitat degradation make it challenging to ensure the successful supplementation of seedlings, placing the survival of wild populations in jeopardy. In this context, it is both necessary and urgent to create an appropriate habitat for the growth of Paphiopedilum in a controlled artificial environment, thereby expanding its population size and ultimately facilitating its return to the wild. To achieve success, it is essential to thoroughly investigate the soil fungal communities in the last remaining habitats of the three Paphiopedilum species, including their spatial variations and responses to the biotic environment.

Considering the unique growth environments of the three Paphiopedilum species, this study posits that these species share certain similarities in habitat preferences while also exhibiting distinct differences. Such differences contribute to variations in soil nutrients, soil fungal community structure, diversity, and the functional groups of soil fungi associated with each species. Uncovering these differences is crucial for understanding the ecological adaptability of the three Paphiopedilum species. In this study, P. armeniacum, P. wenshanense, and P. emersonii were selected as research subjects to comprehensively investigate the environmental characteristics of their remaining habitats. Soil samples were collected from the habitats of these three Paphiopedilum populations, and high-throughput sequencing methods were employed to analyze the soil fungi present. This analysis aimed to clarify the composition and structure of the fungal community, identify fungal functional groups, and assess fungal community diversity. The study revealed dynamic changes in soil fungi within the Paphiopedilum habitats and provided preliminary insights into how the fungal community structure responds to the biotic environment. This research addresses a gap in the understanding of habitat characteristics for the wild populations of these species. Additionally, the findings may serve as a reference for ex situ conservation, artificial breeding environment selection, and the cultivation of these plants.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive investigation of the natural distribution of three Paphiopedilum species, selecting three sites with optimal growth and no anthropogenic disturbances for each species (Fig. 1). P. armeniacum is found in Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province; P. wenshanense is located in Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan Province; and P. emersonii is situated at the junction of Guizhou Province and Guangxi Province. Initially, we observed the last known habitats of the Paphiopedilum species, recording data on latitude, longitude, altitude, slope, aspect, and vegetation type. Sampling was conducted 10 cm outside the dense distribution areas of the Paphiopedilum species. We established the direction of potential seed dispersal as the sampling direction, extracting 20 g of soil samples in three directions at a depth of 5 cm. Soil fungal samples were collected from 27 habitats across the three species. Prior to sampling, the air environment was disinfected with 75% medical alcohol to eliminate undecomposed litter. To ensure the collection of representative soil samples, the soil was transferred to a 4 °C refrigerator within 12 h post-sampling to minimize DNA degradation. For meta-barcode analysis, a small quantity of soil (< 250 mg) was placed in BashingBead™ Lysis Tubes (Zymo Research, Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, UK) to preserve environmental DNA for subsequent extraction and amplification. Soil nutrient test samples were collected following the aforementioned sampling method, with 200 g of soil (from a depth of 0 to 10 cm) obtained from each habitat, placed in sampling bags, and returned to the laboratory33,34.

Soil nutrient analysis

The soil physiochemical properties were analyzed according to Bao and are described briefly as follows35. The pH was determined by the water: soil = 2.5:1 extraction pH meter (PHS-3G) method. The water content was determined by the 105 °C drying–weighing method. The organic carbon content was determined by the KCr2O7-H2SO4 external heating method. Total nitrogen was determined by the semimicro Kjeldahl method; total phosphorus was determined by the HClO4-H2SO4 digestion-molybdenum antimony colorimetric method. Total potassium was determined by NaOH melting-flame spectrophotometry. Available phosphorus was determined by a 0.03 mol/L NH4F-0.025 mol/L HCl extraction-molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric method. Available potassium was extracted by a 1 mol/L neutral NH4OAC-flame photometer. Ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen were determined by a 2 mol/L KCl extraction-continuous flow analyzer. The soil enzyme activities were determined using an enzyme analysis kit (Yangling Xinhua Ecological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanxi, China).

Habitat soil fungal sequencing

DNA was extracted from the samples by the CTAB method, and the extracted DNA was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR extraction was performed using barcode primers and high-fidelity enzymes. The following primer sequences were used: 5’-AAGCTCGTAGTTGAATTTCG-3’ and 5’-CCCAACTATCCCTATTAATCAT-3’36,37. The PCR products were mixed and detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The quantified PCR products were subjected to Illumina HiSeq sequencing. First, Trimmomatic (version 0.33)38 was used to filter the quality of the original data, and then Cutadapt (version 1.9.1) was used to identify and remove the primer sequences39. Subsequently, USEARCH (version 10) was used to splice the double-end reads and remove the chimeras (UCHIME, version 8.1)40. Chimeric sequences were removed to finally obtain high-quality sequences, and the characteristic sequences were taxonomically annotated using the simple Bayes classifier with UNITE as the reference database41.

Data analysis

Soil nutrient difference analysis

The soil nutrients of the three Paphiopedilum species were statistically analyzed by SPSS 22.0. Univariate analysis of variance was used to analyze the means. When the variance analysis results of soil nutrients between different species were significant at the p < 0.05 level, the least significant difference (LSD) test was used to compare the mean values of the soil variables.

Analysis of fungal community structure in the habitat

FLASH (v.1.2.7) was used to merge forward and reverse double-ended sequences from the MiSeq platform. A paired-end reading was obtained for each sample based on a unique barcode sequence. QIIME software was used to remove data clutter, and 97% similarity was used as the standard to divide operational taxonomic units. Usearch was used to remove chimeras, and the RDP classifier Bayesian algorithm was used to perform taxonomic analysis on representative OTU sequences. Species classification was performed using the fungal database Unite8.0/Fungi (Unite Release 8.0) for comparison and identification.

In this study, the abundance of fungal species was analyzed based on the Euclidean distance algorithm, and the FUNGuild online database platform was used to predict the function of soil fungi in three Paphiopedilum species. The Chao1 index, ACE index, Shannon index and Simpson index were used to represent the alpha diversity index, and a t test was used to determine significant differences. ANOSIM was used to verify the reliability of the species grouping. Beta diversity was analyzed by nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) calculated by the Bray‒Curtis distance, and the results were subjected to the Adonis nonparametric variance test. The above analysis was implemented using the BioCloud platform (https://www.biocloud.net/).

To effectively reveal the symbiotic network relationships of the soil fungi in the three Paphiopedilum habitats, the soil fungal species data of the Paphiopedilum plant habitats were filtered under conditions of a relative abundance ≥ 0.1% and at least three sampling points. Spearman correlation was performed on the filtered data set, and a correlation coefficient (ρ) ≥ 0.5 and p < 0.01 were selected to construct the network. The main topological attributes of the network were calculated by using the “igraph” package of R software, and the nodes were calculated and visualized with Gephi software.

The Mantel test was used to explore the effects of habitat soil nutrients on fungal diversity. db-RDA was used to reveal the effects of habitat soil nutrients on soil fungal community changes. Spearman correlation analysis was used to reveal the correlation between habitat soil nutrients and dominant habitat soil fungal groups. The analysis and mapping were achieved using the “vegan” package, “ggcor” package, and “corrplot” package of R software.

Results

Habitat information and soil nutrient characteristics

A habitat survey of three wild Paphiopedilum species revealed that P. armeniacum grows in mountain shrubs at altitudes of approximately 1700–2000 m, typically on slopes ranging from 30° to 55° (Table 1). P. emersonii is found in evergreen and deciduous broad-leaved mixed forests at altitudes of approximately 300–800 m in karst low-mountain hills, where it thrives on very steep slopes of 75° to 90°. P. wenshanense is located in shrubs on both normal and karst landforms, at altitudes of approximately 1500–1600 m. The three species share similar habitat preferences, favoring shady slopes, particularly those facing north and northwest, as well as negative terrain features such as tree roots, stone pits, and stone crevices.

Soil nutrient analysis for the three Paphiopedilum species was conducted using one-way analysis of variance (Table 2). The results indicated no significant differences in total nitrogen, total phosphorus, total potassium, organic matter, available potassium, or pH among the three species. However, the content of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen in the soil of P. emersonii was significantly greater than that in the soil of P. wenshanense. Additionally, the available phosphorus levels in the soils of P. emersonii and P. armeniacum were significantly higher than those found in the soil of P. wenshanense.

Species dilution curve and Venn diagram

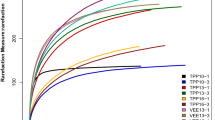

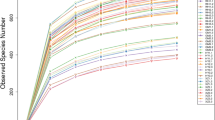

The dilution curve effectively reflects the sequencing depth of the sample sequence. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, at a similarity threshold of 97%, the soil fungal dilution curves for the three Paphiopedilum species exhibited a decreasing trend, suggesting that the sample size adequately represents the soil fungal community within the plant habitat as a whole. A total of 2,161,515 pairs of reads were obtained from 27 fungal habitat samples. Following quality control and the splicing of paired-end reads, a total of 2,154,184 clean reads were generated. Each sample produced a minimum of 79,308 clean reads, with an average of 79,785 clean reads. High-throughput sequencing analysis was conducted based on the 97% similarity tag classification, serving as the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) standard, resulting in the identification of 1,068 operable units. Among these, 452 unique OTUs were identified in the soil of P. emersonii (Fig. 2B), followed by P. wenshanense (n = 232) and P. armeniacum (n = 211). There were 65 OTUs shared between the habitat soils of P. wenshanense and P. armeniacum, 25 OTUs shared between P. armeniacum and P. emersonii, and 46 OTUs shared between P. emersonii and P. wenshanense. Furthermore, 37 common OTUs were identified across the three Paphiopedilum habitat soils.

According to the species annotation presented in Table 3, a total of 336 fungal species were identified, belonging to 11 phyla, 30 classes, 74 orders, 157 families, and 272 genera. In the soil of P. emersonii, 230 fungal species were identified across 10 phyla, 26 classes, 62 orders, 127 families, and 202 genera. In the soil of P. armeniacum, 138 fungal species were identified, representing 9 phyla, 21 classes, 44 orders, 86 families, and 116 genera. Finally, in the soil of P. wenshanense, 145 fungal species were identified, comprising 7 phyla, 21 classes, 52 orders, 98 families, and 126 genera.

Fungi composition and functional group composition in the habitat soil of three paphiopedilum

Figure 3 illustrates the relative abundance of fungal groups in the habitat soil of three Paphiopedilum species at both the phylum and genus levels. In the soil of P. wenshanense, Calcarisporiellomycota emerged as the dominant fungal group, whereas no distinct dominant group was identified in the soil of P. armeniacum. Conversely, the habitat of P. emersonii exhibited dominant fungal groups, including Kickxellomycota, Entorrhizomycota, Olpidiomycota, and Rozellomycota. At the genus level, the habitat soil of P. wenshanense was characterized by the presence of unclassified Sordariomycetes, Sebacina, unclassified Basidiomycota, Boletus, unclassified Boletaceae, Archaeorhizomyces, and other prevalent fungi. In the soil fungal habitat of P. armeniacum, unclassified Thelephoraceae, Hygrocybe, unclassified Serendipitaceae, unclassified Ascomycota, Tomentella, and unclassified Agaricomycetes were identified. The soil of P. emersonii contained Acremonium, unclassified Fungi, unclassified Chaetothyriales, Apodus, unidentified fungi, unclassified Hypocreales, and various other soil fungi.

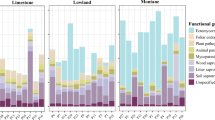

Based on the ecological role of fungi in the environment, we conducted a functional classification and annotation of soil fungi associated with three Paphiopedilum species using the FUNGuild microecological tool. The functions of soil fungi can be categorized into three types based on their nutritional modes: saprophytic, symbiotic, and pathogenic nutrition. In the soils of the three Paphiopedilum species, saprophytic and symbiotic fungi were predominant (Fig. 4A). Notably, the relative abundance of these two nutritional types in the soil of P. armeniacum constituted 98%, while they represented over 80% in the habitats of P. wenshanense and P. emersonii. The fungal functional groups were further classified into ten categories based on their environmental resource absorption (Fig. 4B). These categories included Undefined Saprotroph, Ectomycorrhizal, Undefined-Biotroph, Soil Saprotroph, Fungal Parasite, Wood Saprotroph, Plant Saprotroph, Animal Pathogen, Plant Pathogen, and Orchid Mycorrhizal. Among these, undefined saprophytic fungi and ectomycorrhizal fungi comprised a significant proportion of the soil fungal communities associated with the three Paphiopedilum species, playing crucial ecological roles. In the habitat soil of P. armeniacum, undefined saprophytic fungi, ectomycorrhizal fungi, and undefined biotrophic fungi dominated, accounting for over 95% of the relative abundance, along with some orchid mycorrhizal and animal pathogenic fungi. The primary fungal functional groups in the soil habitat of P. wenshanense included saprophytic fungi, animal pathogens, plant parasitic fungi, plant saprophytic fungi, wood saprophytic fungi, and plant pathogens, among other dominant groups. Similarly, the soil fungal functional groups associated with P. emersonii were diverse, with relatively comparable relative abundances.

Diversity analysis

The alpha diversity analysis of the habitat soil fungal communities associated with the three Paphiopedilum species revealed no significant differences in the ACE and Chao1 indices, indicating that the community abundance of habitat soil fungi was similar among the three species (Fig. 5). However, the Simpson and Shannon indices for P. emersonii were significantly greater than those for both P. armeniacum and P. wenshanense. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in the four diversity indices between P. armeniacum and P. wenshanense.

To clarify the overall differences in the soil fungal community structure among the three Paphiopedilum species, the beta diversity was analyzed via nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on the Bray‒Curtis distance (based on fungal abundance and species presence or absence). Prior to this, to verify the reliability of species as a grouping unit, we used permutational MANOVA. The results showed that the differences in the habitat soil fungal community structure among the three Paphiopedilum species were significantly greater than the intraspecific differences, indicating that the grouping results were reliable (Fig. 6). The R values were 0.214 and 0.388 at the phylum and genus levels, respectively, indicating that the grouping method explained 21.4% and 38.8% of the sample differences, respectively.

Figure 7 presents the results of the NMDS analysis, with the ordination axis set to 2. The stress values (strees) of the soil fungal community associated with the three Paphiopedilum species, assessed at both the phylum and genus classification levels, were found to be less than 0.2, indicating that the results possess explanatory significance. Specifically, the stress values at the phylum and genus levels were 0.0071 and 0.159 (Fig. 7), respectively, suggesting that the differences in the habitat soil fungal community structure among the three Paphiopedilum species are more pronounced at the phylum level.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis (NMDS) at the (a) gate level and (b) genus level. Each point in the figure represents a sample; different colors represent different groups; the elliptical ring represents a 95% confidence ellipse. When the stress is less than 0.1, it can be considered a good sort; when the stress is less than 0.05, it has good representativeness. It is generally believed that when the stress is less than 0.2, NMDS analysis has a certain reliability. The closer the sample is to the coordinate diagram, the greater the similarity.

Soil fungal co-occurrence network of three Paphiopedilum species

To investigate the potential interactions among soil fungi associated with three Paphiopedilum species and the alterations in their co-occurrence networks, we constructed an OTU-level co-occurrence network based on random matrix theory. A consistent threshold (r > 0.6, p < 0.01) was applied for network construction, allowing for a comparative analysis of the changes in the co-occurrence networks. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the habitat soil fungal co-occurrence network of P. emersonii comprised 74 nodes and 606 edges, with 93.56% of the correlations being positive and only 6.44% negative (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the co-occurrence network of soil fungi in the habitat of P. armeniacum contained 77 nodes and 479 edges, with positive correlations accounting for 70.56% and negative correlations for 29.44% (Fig. 8B). The soil fungal co-occurrence network in the habitat of P. wenshanense was the smallest, featuring only 53 nodes and 183 edges; here, positive correlations represented 87.43% while negative correlations constituted 12.57% (Fig. 8C). This study indicates that the co-occurrence networks of soil fungi associated with P. emersonii and P. armeniacum exhibit a high degree of modularity and a substantial proportion of positive interactions. This suggests that these fungal networks contain modules that are resilient to changes in the external environment. Such a symbiotic model may play a crucial role in maintaining community structure, enabling resistance to adverse environmental conditions, and facilitating the effective degradation of organic matter.

Soil fungal co-occurrence network of three Paphiopedilum species in habitats. Each node represents an OTU, and the connection of the nodes represents a strong correlation (Spearman’s r > 0.6), p < 0.01 adjusted by fdr. The edges between the nodes represent a significant correlation between the two OTUs. The red edge indicates a positive correlation, and the green edge indicates a negative correlation.

Relationships between habitat soil fungi and soil nutrients of three paphiopedilum species

The correlation between soil nutrients and their effect on fungal alpha diversity was analyzed using the Mantel test. The results indicated (Fig. 9A) several significant correlations among the soil nutrient factors. Total nitrogen content in the soil was significantly positively correlated with organic carbon, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, and available phosphorus, while total phosphorus exhibited a significant positive correlation with available phosphorus. Conversely, available potassium showed a significant negative correlation with total phosphorus, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, and available phosphorus, and soil pH was significantly negatively correlated with total potassium. Furthermore, soil pH significantly influenced the Shannon and Simpson indices of soil fungi. Redundancy analysis was conducted with soil nutrients, utilizing the ten most dominant fungal taxa as response variables. The results demonstrated that the first axis (Fig. 9B) accounted for 60.41% of the variance, while the second axis explained 20.29% of the variance, together accounting for 80.70% of the changes in the horizontal distribution of the dominant fungal groups, with total nitrogen, organic carbon, and alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen identified as the most significant factors.

Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was employed to elucidate the associations between soil nutrients and dominant fungal groups (Fig. 10). In the P. emersonii habitat, total potassium was significantly negatively correlated with Rozellomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Ascomycota, while it was significantly positively correlated with Basidiomycota. Alkaline nitrogen was significantly negatively correlated with unclassified fungi and Chytridiomycota, whereas pH was significantly positively correlated with both unclassified fungi and Chytridiomycota. In the P. armeniacum habitats, the Rozellomycota, Basidiomycota, and Ascomycota phyla exhibited significant correlations with all nutrient factors, with the exception of total potassium. The abundance of Rozellomycota was found to be negatively correlated with available potassium while simultaneously being positively correlated with total potassium. Conversely, Basidiomycota showed a positive correlation with available potassium but a negative correlation with the other nutrient factors. Similarly, the abundance of Ascomycota was negatively correlated with available potassium and positively correlated with the other phyla. Additionally, a negative correlation was observed between unclassified fungi and total potassium. In the P. wenshanense habitat, unclassified fungi, Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, and Chytridiomycota were significantly correlated with total nitrogen, total phosphorus, organic carbon, alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium, while not showing significant correlations with the remaining factors. Notably, the abundance of Mortierellomycota was significantly negatively correlated with both organic carbon and available potassium, whereas Glomeromycota abundance was significantly negatively correlated with pH.

Discussion

Ex situ conservation, a critical strategy for mitigating the risk of orchid extinction, has consistently played a vital role in biodiversity conservation42,43. However, the efficacy of ex situ conservation is contingent upon a comprehensive understanding of the ecological habits of the species, as well as the ecological and biological characteristics of their living environments. This is particularly true for species such as orchids, which are highly reliant on fungal symbiosis; thus, elucidating the characteristics of their habitat soil environment is a prerequisite for successful ex situ conservation. While some studies have examined the habitats of wild orchids, most have focused on distribution patterns, habitat preferences, and habitat evaluations, often neglecting the specific habitat characteristics essential to orchids44,45,46,47. In this study, targeted sampling methods were employed to investigate the habitats of wild populations of Paphiopedilum species. The study revealed the habitat characteristics, soil nutrients, and soil fungal microbial community structures of three rare and endangered Paphiopedilum species, while also exploring the interrelationships among these factors. This information will be instrumental in constructing simulated environments and selecting sites for future field reintroductions in ex situ conservation efforts.

The results indicated that the three species of Paphiopedilum preferred to thrive in low-lying areas characterized by high vegetation canopy density and ventilation. The relative humidity of these habitats was notably high, which enhanced the resilience of Paphiopedilum species to arid climatic conditions. However, this unfavorable terrain may also impede population dispersal. The physical and chemical properties of the soil across the three species of Paphiopedilum were largely similar, with the exception of significant differences in available nitrogen and phosphorus, potentially linked to the pronounced topographic heterogeneity in the region. A survey revealed that these species are confined to a narrow distribution within the mountainous areas of Southwest China. This region features both karst and non-karst landforms, a variety of soil-forming bedrock, an intricate distribution of soil types, and considerable climate variability, resulting in spatial and temporal heterogeneity48. The complexity of this environmental backdrop has led to variations in soil nutrients within the habitats of Paphiopedilum species, which may contribute to significant differences in soil nutrient levels at various distribution points for the same species49,50,51. Furthermore, the soil fungal community serves as a crucial factor influencing plant growth and distribution, acting as a key intermediary that indirectly affects these processes. Its composition and structure are often dictated by prevailing environmental conditions52,53.

In this study, the number of soil-specific operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in the habitat of P. emersonii was greater than that observed in the other two species of Paphiopedilum. This finding indicates a higher diversity of soil-specific fungi in the P. emersonii habitat, suggesting a relationship between habitat characteristics and fungal diversity. A survey revealed that the habitat of P. emersonii primarily consists of humus soil, which is rich in fungal populations. In contrast, P. wenshanense and P. armeniacum are found in high-elevation areas of Yunnan (1500–2000 m above sea level), where the subtropical mountain monsoon climate is characterized by prolonged sunshine and low relative humidity, factors that limit the diversity of soil fungi. The composition and structure of the fungal communities associated with the three Paphiopedilum species exhibited differences at both the phylum and genus levels, with distinct dominant fungal groups identified. These compositional differences may arise from two primary factors: first, the mycorrhizal characteristics of different Paphiopedilum species may selectively favor fungal groups that form symbiotic relationships, thereby altering the fungal community structure in the habitat soil through mechanisms such as alternation, antagonism, and competition during the growth process54,55,56. On the other hand, there are notable differences in the growth environments of various Paphiopedilum species. In particular, the environmental heterogeneity resulting from geographical distribution serves as a direct environmental factor influencing the composition of fungal communities in these habitats57,58. To adapt to their surroundings, fungi employ different nutritional strategies, which represent a survival mechanism that enables them to thrive under varying living conditions59,60. In this study, saprophytic fungi and ectomycorrhizal fungi were found to be dominant in the soil of the three Paphiopedilum species, thereby providing a substantial material basis and symbiotic fungal resources essential for plant survival. It is widely accepted that the diversity of fungal functional groups in the soil correlates with environmental complexity61,62, which may be linked to the specific habitat preferences of Paphiopedilum species. This group of plants thrives in environments characterized by high vegetation canopy density, good ventilation, and appropriate shading, often growing in rock joints or humus layers near the bases of other woody plants. Such habitats inherently foster a rich presence of saprophytic fungi and ectomycorrhizal fungi, playing a crucial ecological role in promoting plant growth and facilitating nutrient cycling63,64,65,66. Ectomycorrhizal groups may serve as the initial catalyst for the germination of Paphiopedilum seeds and represent the primary source of heterotrophic fungi during the early stages of Paphiopedilum species development. Saprophytic fungi enhance the cycling of habitat materials, improve soil texture, and increase both water and air permeability67,68, thereby creating nutritional conditions and habitat characteristics that are more favorable for the growth of Paphiopedilum species. Additionally, we observed a small presence of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in the habitat soil. Previous research69 has indicated that when the fungal community in the habitat soil provides the foundational material for orchid mycorrhizal fungi, these mycorrhizal fungi can establish themselves within the habitat soil alongside the growth of Paphiopedilum, further facilitating the germination of orchid seeds70,71.

The alpha diversity index is a crucial metric for assessing community characteristics in ecology and biological sciences. This study demonstrated that the habitat soil fungal diversity indices of three Paphiopedilum species align with the observed number of fungal-specific operational taxonomic units (OTUs), indicating a correlation between fungal community diversity and the quantity of fungal-specific OTUs. Beta diversity highlights the variations in community structure across a gradient or the directional changes within a specific range of that gradient72,73. Furthermore, this study confirmed significant differences in the habitat soil fungal community structure among the three Paphiopedilum species. Despite the close genetic relationships among these species15, variations in their historical geographical distributions and habitat conditions likely contribute to the observed differences in soil fungal community structures, reflecting distinct habitat selection preferences among the three Paphiopedilum species. A microbial co-occurrence network serves as a powerful tool for elucidating the coexistence relationships among microorganisms. This study demonstrated that the soil fungal habitats of the three Paphiopedilum species were predominantly characterized by positive symbiotic interactions, with a markedly small proportion of negative symbiotic interactions. This finding contrasts sharply with the results of biological co-occurrence network analyses conducted on other research subjects74,75. We hypothesize that the soil fungal communities in these habitats have reached a mature state, allowing for the harmonious coexistence of numerous fungi that collectively fulfill biological roles76,77,78. This is further evidenced by the diversity of soil fungal functional groups associated with the three Paphiopedilum species. Additionally, we propose that this model of positive effect-based microbial coexistence enhances the ability of soil microorganisms to withstand adverse environmental conditions, thereby providing essential nutrients for Paphiopedilum species in extreme environments79. However, this hypothesis requires further validation.

The fungal community, which plays a crucial role in the soil environment, is also influenced by soil nutrients80,81,82,83,84,85. This study elucidates the effects of habitat-related nutrient changes on the soil fungal community structure associated with three Paphiopedilum species. The Mantel test indicated that pH significantly influences the diversity of the soil fungal communities across these species. Soil pH affects diversity by directly impacting the survival, competition, growth, and reproductive efficiency of soil fungi86. Furthermore, soil pH serves as an indirect indicator of variations in overall environmental conditions87. Liu et al. established that soil pH is a significant predictor of soil fungal groups in Southwest China88. Although this study revealed a direct correlation between soil pH values and nutrient availability, it could not confirm the direct or indirect effects on orchids. However, it can be inferred that soil pH influences the distribution and growth of orchids by affecting the efficiency of soil nutrient supply and the dynamic structure of soil fungi. In future ex situ conservation efforts for Paphiopedilum species, monitoring soil pH should be prioritized. Additionally, this study identified relationships between dominant fungal groups and soil nutrients, noting that the compositions of the dominant habitat soil fungal groups associated with the three Paphiopedilum species were complex. The identified fungal groups include Rozellomycota, Olpidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, Kickxellomycota, Glomeromycota, Entorrhizomycota, Chytridiomycota, Calcarisporielomycota, Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, among others. Most of these groups exhibited significant associations with soil nutrients, corroborating findings from previous research89,90. This suggests that fluctuations in soil properties can lead to changes in fungal community structure. Furthermore, fungi are crucial microorganisms in soil, playing a vital role in the material and energy cycles within soil systems, as well as in improving soil structure through the decomposition of organic matter and the release of nutrients. The habitat soil samples in this study were all collected from a specific orchid habitat. While the correlation between habitat soil nutrients and fungal communities was established, quantifying the influence of orchid species and habitat soil on the soil fungi remains a challenge and an area for further investigation in future research. Nonetheless, the findings regarding soil nutrients and fungal communities in these habitats can provide valuable scientific insights for future ex situ conservation measures.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that the three species of Paphiopedilum thrived in low-lying, shaded, and well-ventilated environments, characterized by highly heterogeneous habitat conditions. While no significant differences in soil nutrients were observed among the different species, notable variability in soil nutrients was evident at various distribution points within the same species. Analysis of the soil fungal community structure across the habitats revealed significant differences in community composition among the three Paphiopedilum species; specifically, the habitat of P. emersonii exhibited a greater number of unique operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and fungal species. Furthermore, the soil fungal functional groups associated with the three Paphiopedilum species were largely similar, primarily consisting of saprophytic, symbiotic, and pathotrophic fungi. This included Undefined Saprotroph, Ectomycorrhizal, Undefined Biotroph, Soil Saprotroph, Fungal Parasite, Wood Saprotroph, and Plant Saprophytic fungi. Significant differences in soil fungal communities were noted among the three Paphiopedilum species, with the Simpson and Shannon indices for P. emersonii being significantly higher than those for the other two species. Additionally, microbial co-occurrence network analysis revealed that the symbiosis among soil fungi in the three Paphiopedilum species was predominantly positive, with P. emersonii demonstrating a higher degree of modularity in its symbiotic network. Nutrient levels significantly influenced the Shannon and Simpson indices across the three Paphiopedilum species, with soil nutrients accounting for 80.70% of the horizontal variations observed in the dominant soil fungal groups. The primary groups of soil fungi within each Paphiopedilum habitat were significantly correlated with soil nutrients, suggesting an interactive relationship between soil nutrients and soil fungal communities.

Data availability

Raw amplicon sequence data related to this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) under Bioproject PRJNA888962. Given that the study’s subject (P. armeniacum, P. emersonii, P.wenshanense) belongs to rare or endangered species in the IUCN standard. We collected their habitat soil with the permission of the local conservation authority, and there was no damage to the plants.

References

Herrera, H., García, R. I., Meneses, C., Pereira, G. & Arriagada, C. Orchid mycorrhizal interactions on the Pacific Side of the Andes from Chile. A review. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nut. 19(1), 187–202 (2019).

Chengru, L. et al. A review for the breeding of orchids: current achievements and prospects. Hortic. Plant. J. 7(05), 380–392 (2021).

Chase, M. W. et al. Updated classification of Orchidaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 177(2), 151–174 (2015).

Kull, T. & Hutchings, M. J. A comparative analysis of decline in the distribution ranges of orchid species in Estonia and the United Kingdom. Biol. Conserv. 129(1), 31–39 (2006).

Vishwakarma, S. K., Singh, N. & Kumaria, S. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the PAL genes from the orchids Apostasia Shenzhenica, Dendrobium catenatum and Phalaenopsis Equestris. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41(4), 1295–1308 (2023).

Fernandez, M., Kaur, J. & Sharma, J. Co-occurring epiphytic orchids have specialized mycorrhizal fungal niches that are also linked to ontogeny. Mycorrhiza. 33(1–2), 87–105 (2023).

Mennicken, S., Paula, C., Vogt-Schilb, H. & Jersakova, J. Diversity of Mycorrhizal Fungi in Temperate Orchid species: comparison of Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent methods. J. Fungi. 10(2), 92–92 (2024).

Bazzicalupo, M., Calevo, J., Smeriglio, A. & Cornara, L. Traditional, therapeutic uses and Phytochemistry of Terrestrial European orchids and implications for Conservation. Plants-Basel. 12(2), 257 (2023).

Vladan, D. et al. Patterns of distribution, abundance and composition of forest terrestrial orchids. Biodivers. Conserv. 29(prepublish), 4111–4134 (2020).

Wraith, J., Norman, P. & Pickering, C. Orchid conservation and research: an analysis of gaps and priorities for globally red listed species. Ambio. 49(10), 1601–1611 (2020).

Tian, F. et al. Isolation and identification of beneficial orchid mycorrhizal fungi in Paphiopedilum barbigerum (Orchidaceae). Plant. Signal. Behav. 17(1), 2005882 (2022).

Tsai, C. C., Liao, P. C., Ko, Y. Z., Chen, C. H. & Chiang, Y. C. Phylogeny and historical Biogeography of Paphiopedilum Pfitzer (Orchidaceae) based on Nuclear and Plastid DNA. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 126 (2020).

Zeng, S. et al. Asymbiotic seed germination, seedling development and reintroduction of Paphiopedilum Wardii Sumerh., an endangered terrestrial orchid. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam. 138, 198–209 (2012).

Wen-Ke, Y., Tai-Qiang, L., Shi-Mao, W., Patrick, M. F. & Jiang-Yun, G. Ex situ seed baiting to isolate germination-enhancing fungi for assisted colonization in Paphiopedilum Spicerianum, a critically endangered orchid in China. Glob Ecol. Conserv. 23, e01147 (2020).

Tsai, C., Liao, P., Ko, Y., Chen, C. & Chiang, Y. Phylogeny and historical Biogeography of Paphiopedilum Pfitzer (Orchidaceae) based on Nuclear and Plastid DNA. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 126 (2020).

Waud, M., Busschaert, P., Lievens, B. & Jacquemyn, H. Specificity and localised distribution of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil may contribute to co-existence of orchid species. Fungal Ecol. 20, 155–165 (2016).

Ye, P. et al. Geographical distribution and relationship with environmental factors of Paphiopedilum Subgenus Brachypetalum Hallier (Orchidaceae) Taxa in Southwest China. Diversity. 13(12), 634 (2021).

Dove, A. et al. Fungal Community Composition at the last remaining wild site of Yellow Early Marsh Orchid (Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp. Ochroleuca). Microorganisms. 11(8), 2124 (2023).

Reiter, N., Lawrie, A. C. & Linde, C. C. Matching symbiotic associations of an endangered orchid to habitat to improve conservation outcomes. Ann. Bot-London. 122(6), 947–959 (2018).

Jacquemyn, H. et al. Mycorrhizal associations and Trophic modes in coexisting orchids: an ecological continuum between auto- and Mixotrophy. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1497 (2017).

Favre-Godal, Q., Gourguillon, L., Lordel-Madeleine, S., Gindro, K. & Choisy, P. Orchids and their mycorrhizal fungi: an insufficiently explored relationship. Mycorrhiza. 30(1), 5–22 (2020).

Xing, X. et al. Similarity in mycorrhizal communities associating with two widespread terrestrial orchids decays with distance. J. Biogeogr. 47(2), 421–433 (2020).

Johnson, L. J. A. N., Gónzalez Chávez, M. D. C. A., Carrillo González, R., Porras Alfaro, A. & Mueller, G. M. Vanilla aerial and terrestrial roots host rich communities of orchid mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal fungi. Plants People Planet. 3(5), 541–552 (2021).

Vogt-Schilb, H. et al. Altered rhizoctonia assemblages in grasslands on ex-arable land support germination of mycorrhizal generalist, not specialist orchids. New. Phytol. 227(4), 1200–1212 (2020).

Kendon, J. P. et al. Recovery of mycorrhizal fungi from wild collected protocorms of Madagascan endemic orchid Aerangis Ellisii (B.S. Williams) Schltr. And their use in seed germination in vitro. Mycorrhiza. 30(5), 567–576 (2020).

Cavagnaro, T. R. Soil moisture legacy effects: impacts on soil nutrients, plants and mycorrhizal responsiveness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 95, 173–179 (2016).

Shen, C., Wang, J., He, J. Z., Yu, F. H. & Ge, Y. Plant Diversity enhances soil fungal diversity and Microbial Resistance to Plant Invasion. Appl. Environ. Microb. 87(11), e00251–21 (2021).

Mujica, M. I. et al. Relationship between soil nutrients and mycorrhizal associations of two Bipinnula species (Orchidaceae) from central Chile. Ann. Bot-London. 118(1), 149–158 (2016).

Mennicken, S. et al. Orchid–mycorrhizal fungi interactions reveal a duality in their network structure in two European regions differing in climate. Mol. Ecol. 32(12), 3308–3321 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Variation in mycorrhizal communities and the level of mycoheterotrophy in grassland and forest populations of Neottia ovata(Orchidaceae). Funct. Ecol. 37(7), 1948–1961 (2023).

Yokoya, K. et al. Fungal Diversity of Selected HabitatSpecific Cynorkis Species (Orchidaceae) in the Central Highlands of Madagascar. Microorganisms. 9(4), 792 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. The structure and diversity of bacteria and fungi in the roots and rhizosphere soil of three different species of Geodorum. BMC Genom. 25(1), 222–222 (2024).

Bosso, L. et al. Plant pathogens but not antagonists change in soil fungal communities across a land abandonment gradient in a Mediterranean landscape. Acta Oecol. 78, 1–6 (2017).

Yunfeng, J., Xiuqin, Y. & Fubin, W. Composition and spatial distribution of Soil Mesofauna along an Elevation gradient on the North Slope of the Changbai Mountains. China Pedosphere. 25(6), 811–824 (2015).

BAO, S. D. Agrochemical Analysis of soil (China Agriculture, 2000).

Dai, M. et al. Negative and positive contributions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal taxa to wheat production and nutrient uptake efficiency in organic and conventional systems in the Canadian prairie. Soil Biol. Biochem. 74, 156–166 (2014).

De Beenhouwer, M. et al. Changing soil characteristics alter the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi communities of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) in Ethiopia across a management intensity gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 91, 133–139 (2015).

Bolger, A. M., Loe, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 30(15), 2114–2120 (2014).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17(1), 10–12 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 10(10), 996–998 (2013).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinf. (Oxford England). 27(16), 2194–2200 (2011).

Zhou, Q. et al. Mesophytic and less-disturbed mountainous habitats are important for in situ conservation of rare and endangered plants. Glob Ecol. Conserv. 44, e2488 (2023).

Abeli, T. et al. Ex situ collections and their potential for the restoration of extinct plants. Conserv. Biol. 34(2), 303–313 (2020).

Qiu, L. et al. Contrasting range changes of terrestrial orchids under future climate change in China. Sci. Total Environ. 895, 165128 (2023).

Koju, L. et al. Spatial patterns, underlying drivers and conservation priorities of orchids in the central Himalaya. Biol. Conserv. 283, 110121 (2023).

Parra-Sanchez, E., Freckleton, R. P., Hethcoat, M. G., Ochoa-Quintero, J. M. & Edwards, D. P. Transformation of natural habitat disrupts biogeographical patterns of orchid diversity. Biol. Conserv. 292, 110538 (2024).

Hussain, K. et al. Temperature, topography, woody vegetation cover and anthropogenic disturbance shape the orchids distribution in the western Himalaya. S Afr. J. Bot. 166, 344–359 (2024).

He, Y., Wang, L., Niu, Z. & Nath, B. Vegetation recovery and recent degradation in different karst landforms of southwest China over the past two decades using GEE satellite archives. Ecol. Inf. 68, 101555 (2022).

Netherway, T. et al. Pervasive associations between dark septate endophytic fungi with tree root and soil microbiomes across Europe. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 159 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. A highly conserved core bacterial microbiota with nitrogen-fixation capacity inhabits the xylem sap in maize plants. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 3361 (2022).

Singh, B. K. et al. Relationship between assemblages of mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria on grass roots. Environ. Microbiol. 10(2), 534–541 (2008).

Boddy, L. & Hiscox, J. Fungal Ecology: principles and mechanisms of colonization and competition by Saprotrophic Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 4(6), 293–308 (2016).

John, N. K. Variation in Plant Response to Native and ExoticArbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Ecology. 84(9), 2292–2301 (2003).

Causevic, S. et al. Niche availability and competitive loss by facilitation control proliferation of bacterial strains intended for soil microbiome interventions. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 2557 (2024).

Hu, L. et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 2738 (2018).

Svenningsen, N. B. et al. Suppression of the activity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi by the soil microbiota. ISME J. 12(5), 1296–1307 (2018).

Kivlin, S. N., Winston, G. C., Goulden, M. L. & Treseder, K. K. Environmental filtering affects soil fungal community composition more than dispersal limitation at regional scales. Fungal Ecol. 12, 14–25 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Climate and geochemistry at different altitudes influence soil fungal community aggregation patterns in alpine grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 881, 163375 (2023).

Zheng, Z. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities associated with two dominant species differ in their responses to long-term nitrogen addition in temperate grasslands. Funct. Ecol. 32(6), 1575–1588 (2018).

Gilchrist, M. A., Sulsky, D. L. & Pringle, A. Identifying fitness andoptimal life-history strategies for an asexual filamentous fungus. Evolution 60(5), 970–979 (2006).

Chen, W. et al. Soil microbial network complexity predicts ecosystem function along elevation gradients on the Tibetan Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 172, 108766 (2022).

Jiao, S., Lu, Y. & Wei, G. Soil multitrophic network complexity enhances the link between biodiversity and multifunctionality in agricultural systems. Global Change Biol. 28(1), 140–153 (2022).

Murat, C. et al. Pezizomycetes genomes reveal the molecular basis of ectomycorrhizal truffle lifestyle. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2(12), 1956–1965 (2018).

Kadowaki, K. et al. Mycorrhizal fungi mediate the direction and strength of plant-soil feedbacks differently between arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal communities. Commun. Biol. 1, 196 (2018).

Anthony, M. A. et al. Fungal community composition predicts forest carbon storage at a continental scale. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 2385–2385 (2024).

Cahanovitc, R., Livne-Luzon, S., Angel, R. & Klein, T. Ectomycorrhizal fungi mediate belowground carbon transfer between pines and oaks. ISME J. 16(5), 1420–1429 (2022).

Kang, P. et al. Soil saprophytic fungi could be used as an important ecological indicator for land management in desert steppe. Ecol. Indic. 150, 110224 (2023).

Francioli, D. et al. Plant functional group drives the community structure of saprophytic fungi in a grassland biodiversity experiment. Plant. Soil. 461(1–2), 91–105 (2021).

Jacquemyn, H. et al. Habitat-driven variation in mycorrhizal communities in the terrestrial orchid genus Dactylorhiza. Sci. Rep-UK. 6(1), 37182 (2016).

Tsulsiyah, B., Farida, T., Sutra, C. L. & Semiarti, E. Important role of Mycorrhiza for seed germination and growth of Dendrobium Orchids. J. Trop. Biodivers. Biotechnol. 6(2), 60805 (2021).

Darmawati, I. A. P., Astarini, I. A., Yuswanti, H. & Fitriani, Y. Pollination compatibility of Dendrobium spp. orchids from Bali, Indonesia, and the effects of adding organic matters on seed germination under in vitro culture. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 22(5), 2554–2559 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. Integrated biogeography of planktonic and sedimentary bacterial communities in the Yangtze River. Microbiome 6(1), 1–14 (2018).

Anderson, M. J. et al. Navigating the multiple meanings of beta diversity: a roadmap for the practicing ecologist. Ecol. Lett. 14(1), 19–28 (2011).

Qiao, Y. et al. Core species impact plant health by enhancing soil microbial cooperation and network complexity during community coalescence. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 188, 109231 (2024).

Zhai, C. et al. Soil microbial diversity and network complexity drive the ecosystem multifunctionality of temperate grasslands under changing precipitation. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167217 (2024).

Ma, B. et al. Earth microbial co-occurrence network reveals interconnection pattern across microbiomes. Microbiome 8(1), 1–12 (2020).

Ji, L. et al. The Preliminary Research on shifts in Maize Rhizosphere Soil Microbial communities and Symbiotic Networks under different fertilizer sources. Agronomy. 13(8), 2111 (2023).

Saha, S. et al. Microbial Symbiosis: A Network towards Biomethanation. Trends Microbiol. 28(12), 968–984 (2020).

Ge, J., Li, D., Ding, J., Xiao, X. & Liang, Y. Microbial coexistence in the rhizosphere and the promotion of plant stress resistance: a review. Environ. Res. 222, 115298 (2023).

Jing, X. et al. Soil microbial carbon and nutrient constraints are driven more by climate and soil physicochemical properties than by nutrient addition in forest ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 141, 107657 (2020).

Zhong, Z. et al. Adaptive pathways of soil microorganisms to stoichiometric imbalances regulate microbial respiration following afforestation in the Loess Plateau, China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 151, 108048 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Temporal and spatial variation of soil microorganisms and nutrient under white clover cover. Soil Tillage. Res. 202, 104666 (2020).

Coonan, E. C. et al. Microorganisms and nutrient stoichiometry as mediators of soil organic matter dynamics. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 117(3), 273–298 (2020).

Bosso, L., Scelza, R., Testa, A., Cristinzio, G. & Rao, M. A. Depletion of Pentachlorophenol Contamination in an agricultural soil treated with byssochlamys Nivea, Scopulariopsis Brumptii and Urban Waste Compost: A Laboratory Microcosm Study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 226(6), 1–9 (2015).

He, D. et al. Composition of the soil fungal community is more sensitive to phosphorus than nitrogen addition in the alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Biol. Fert Soils. 52(8), 1059–1072 (2016).

Kang, E. et al. Soil pH and nutrients shape the vertical distribution of microbial communities in an alpine wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 774, 145780 (2021).

Naz, M. et al. The soil pH and heavy metals revealed their impact on soil microbial community. J. Environ. Manage. 321, 115770 (2022).

Liu, D., Liu, G., Chen, L., Wang, J. & Zhang, L. Soil pH determines fungal diversity along an elevation gradient in Southwestern China. Sci. China Life Sci. 61(6), 718–726 (2018).

Zhang, T., Wang, N. & Yu, L. Soil fungal community composition differs significantly among the Antarctic, Arctic, and Tibetan Plateau. Extremophiles. 24(6), 821–829 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of plants and soil microorganisms on organic carbon and the relationship between carbon and nitrogen in constructed wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut R. 30(22), 62249–62261 (2023).

Funding

The project was commissioned by National Natural Foundation, China. Project Number: 32360101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li Tian wrote the main manuscript text and Feng Liu and Yang Zhang prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Mingtai An reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We complied with all relevant institutional, national and international guidelines in experimental research and field studies on plants. Material sampling done with permission by the Department of Wildlife Conservation and Nature Reserve Management of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, L., An, M., Liu, F. et al. Fungal community characteristics of the last remaining habitat of three paphiopedilum species in China. Sci Rep 14, 24737 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75185-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75185-8