Abstract

The paleoenvironmental evolution of the Abrolhos Depression (AD) on the southern Abrolhos Shelf during the global post-Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) transgression is investigated through benthic foraminifera analysis. Downcore sediment samples (core DA03A-5B) collected at a depth of 63 m provide insights into the formation and paleoenvironmental variations of AD over the past 18 kyr BP. The core is divided into four biofacies based on foraminifera assemblages. At the base, the presence of carbonate concretions indicates a karstic surface, marking the initiation of the paleolagoon formation at approximately 13 kyr BP with low density of foraminifera, where species such as Elphidium sp. and Hanzawaia boueana (EH Biofacies) were more abundant. During the Younger Dryas (YD) (12.8–12.5 kyr BP), the AD exhibits two distinct phases: an initially confined lagoon environment with reduced circulation characterized by the dominance of the species Ammonia tepida (At Biofacies), followed by increased circulation characterized by higher density, richness, and diversity of benthic foraminifera. The end of the YD is identified by a significant biofacies change, indicative of a shallow marine environment, where the dominant species were A. tepida and Elphidium excavatum (AE Biofacies), supported by sedimentological and geochemical proxies. This paleoenvironmental shift is associated with Meltwater Pulse (MWP) -1B, suggesting a connection to a shallow marine environment. As sea levels continue to rise, the AD transitions into an open marine setting. However, around 8 kyr BP, a change occurs with the absence of A. tepida and the occurrence of planktonic and other benthic foraminifera typical of the outer shelf, indicating depths greater than 50 m (HQ Biofacies). The findings highlight the complex interplay between climate fluctuations, sea-level changes, and the formation of coastal environments during the LGM transgression. This study contributes to our understanding of paleoenvironmental dynamics, adding valuable insights to the evolutionary history of AD. The results emphasize the importance of integrating benthic foraminifera analysis, radiocarbon dating, and geochemical proxies to reconstruct paleoenvironments accurately. Overall, this research enhances our knowledge of global continental shelf evolution during the post-LGM transgression and provides valuable information for future paleoenvironmental studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Quaternary Period is characterized by substantial climatic fluctuations, including glacial and interglacial periods, leading to cycles of eustatic sea-level variations1. These variations are driven by transgressive and regressive processes, where sea level rises and falls, respectively. During the global last glacial maximum (~ 20.0 kyr BP), sea level was approximately 120 m below, exposing the continental shelf2,3,4,5. In general, during deglaciation periods, rates of sea-level rise were typically high6. However, post-last glacial maximum transgressions experienced intermittent periods of stillstands4. These stillstands facilitated the formation of coastal environments, subsequently drowned during meltwater pulses associated with higher rates of sea-level rise. Consequently, the inundation of the continental shelf during deglaciation led to a transformation from typically continental to coastal/estuarine, and eventually to open marine sedimentary environments7,8. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction serves as a valuable tool to investigate the sedimentary response to shelf/coastal flooding, with foraminiferal biofacies analysis being a key method employed.

The extensive usage of foraminifera in paleoceanographic research stems from their well-defined stratigraphic and geographic distributions, along with their well-documented ecological, biological, and taxonomic characteristics9,10. These characteristics enable detailed insights into sediment age and depositional circumstances11, thus contributing to a comprehensive understanding of past environmental conditions and Earth’s geological history.

The densities and distributions of benthic foraminifera are influenced by various environmental parameters, such as temperature, salinity, oxygen content, nutrient availability, and sediment type12,13,14,15,16,17. Changes in these parameters might reflect variations in foraminifera abundance, diversity, presence or absence of certain species, as well as the vertical distribution within sediment deposits and the composition of species assemblages15. Using benthic foraminifera assemblages, it is often possible to reconstruct paleoenvironmental conditions by estimating variations in specific environmental parameters15.

During the deglaciation post-last glacial maximum, a centennial event known as the Younger Dryas (YD) (12.9 to 11.7 kyr BP) marks a cooling temperature period that is also associated with a stillstand4. The establishment of coastal systems during the YD stillstand is described wordwide8,18,19,20.

The Abrolhos Depression (AD) is a morphological feature located in the southern Abrolhos Shelf, eastern Brazilian margin. The pionner work of Vicalvi et al.21 interpreted the AD as a Holocene paleolagoon, strictly connected to the sea through the Besnard Channel. Cetto et al.20, comparing geomorphological depth signatures and published sea-level curves, inferred that the formation of a barrier-lagoon system within of the AD had been occurred between the final phase of the Bølling-Allerød (B-A) interstadium and the end of the YD, favored by the stability of the accommodation space in a slowstand context. Contemporaneously, would be observed the development of clastic features of an inter-lagoonal delta around the mouths (e.g. barrier islands, sand banks and bars) and a proximal main depocenter, with low hydrodynamics and prone to accumulation of fine sediments from the continental drainage. According to those authors, this coastal system were abruptly drowned in face of the MWP-1B, imediatelly after the YD, evolving to an embayment of increased communication with the sea until the end of this eustatic pulse. This evolutionary timeline of AD was confirmed by the seismic and chronostratigraphic analyses of Bastos et al.8 and Cetto et al.7, which recorded a ravinement surface associated with an abrupt facies shift between the remanent lagoonal terrigenous muds and the upper mixed deposits of the transitional phase.

Adding the ecology of benthic foraminifera as an enlightening proxy, the main goal of this study is to refine the paleoenvironmenal reconstruction of the AD during the YD and in the following last stages of the deglaciation. We also aim to answer the following specific goals: (i) produce a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis of benthic foraminifera to accurately define the biofacies based on species distribution patterns; (ii) investigate the impact of meltwater pulse 1B (MWP 1B) on variations in biofacies and paleoenvironments; and (iii) establish correlations with available sedimentological and geochemical data in order to characterize the paleoenviroments. Furthermore, this research seeks to enhance existing models of paleoenvironmental and paleoecological evolution for the last deglaciation, focusing on the YD and MWP 1B. This investigation is based on a multiproxy approach including benthic foraminifera biofacies, sedimentology (grain size and composition), elemental analysis (C/N) and C, N isotope results. The sedimentary core was also radiocarbon dated.

Results

The benthic foraminifera analysis conducted along the sedimentary core collected at the AD (Fig. 1) show the occurrence of 85 taxa, including 69 species and 16 genera. This result represents a mixture of taxa such as rotaliids, miliolids, textulariids, spirillinids, hormosinids, nodosariids, polymorphinids, loftusiids, and vaginulinids. The main species found are shown in Fig. 2, which includes Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images.

In general, the benthic foraminiferal tests were well-preserved. The highest diversity of species was found in hyaline forms (61%), followed by porcelaneous (33%) and agglutinated (5%). Specimens that presented corroded, fragmented tests or even in a state of juvenile development were classified at the lowest possible taxonomic level. According to the frequency calculation, we have 7 constant taxa (f > 50%), 18 accessories (f = 50 − 26%), and 60 (f < 25%) which could be considered rare taxa throughout the downcore. The most frequent species from the base (288 cm) to the top (0 cm) are Elphidium excavatum and Ammonia tepida, followed by Elphidium poeyanum, Hanzawaia boueana, Quinqueloculina lamarckiana, Quinqueloculina venusta and Bolivina striatula.

Images of SEM of the main species of benthic foraminifera found downcore. The scale bar is 100 μm. (A) Ammonia tepida (sample 141 cm); (B) Nonionoides grateloupii (sample 71 cm); (C) Pseudononion japonicum (sample 71 cm); (D) Elphidium excavatum (sample 2 cm); (E) Bolivina striatula (sample 281 cm); (F) Cibicides fletcheri (sample 91 cm); (G) Elphidium crispum (sample 2 cm); (H-I) Neoeponides sp. (H. dorsal view; I. ventral view – sample 11 cm); (J) Bigenerina nodosaria (sample 2 cm); (K) Quinqueloculina lamarckiana (sample 11 cm); (L) Sigmamiliolinella australis (sample 101 cm); (M) Quinqueloculina venusta (sample 31 cm); (N-O) Hanzawaia boueana (N. dorsal view; O. ventral view – sample 2 cm); (P) Cornuspira involvens (sample 51 cm); (Q) Peneroplis planatus (sample 2 cm); (R) Rosalina floridana (sample 71 cm); and (S) Amphistegina radiata (sample 31 cm).

The density of foraminifera exhibited variations along the sediment downcore, revealing distinct patterns (Fig. 3). Towards the base (samples 288 –196 cm), density values dropped below 100 ind./cm³, with significant decreases in samples 288 and 261, reaching values below 10 ind./cm³. In the range of 191 –171 cm, densities remained consistently below 176 ind./cm³. Notably, the 161 –111 cm interval displayed substantial fluctuations, ranging from 353 to 3,354 ind./cm³. Among these, the 141 cm sample showed the highest density of 3,354 ind./cm³, dominated by the species A. tepida. On the other hand, the 101 cm sample exhibited a notable decline, measuring 736 ind./cm³. Densities between samples 91 –61 cm ranged from 1,581 to 1,907 ind./cm³. The 41 –21 cm interval presented the highest densities, ranging between 3,763 and 4,211 ind./cm³, implying a potential shift towards more favorable conditions. These findings elucidate the spatial distribution and temporal dynamics of foraminifera abundance along the sediment core, highlighting environmental fluctuations and potential ecological shifts.

Graph with compiled data from core DA03A_5B: Distribution of species with relative abundance > 1.4% identified; Ecological Indices: Density; Species Richness; Shannon Diversity; Equitability ; AE Index; Geochemical Data including values for CaCO3content, total organic matter content, and C/N ratio7; Sediment Textural Distribution (% gravel, sand, and mud)7; and Radiocarbon Dating (the depth of the 14C datings is reported as sum of core water depth (63 m) plus the sample depth)7.

Species richness values near the base (288 − 271 cm) ranged from 27 to 33 taxa, indicating higher diversity compared to the subsequent sedimentary package (261 − 121 cm) with values between 13 and 4 taxa. The topmost layer (111-2 cm) exhibited a wide range of species richness, ranging from 23 to 60 taxa, representing the highest values observed. Furthermore, Shannon diversity index revealed that the base of the core (288 − 261 cm) exhibited greater diversity (H’ < 1) compared to the next sedimentary section until the 111 cm sample (H’ = 1.7). From the 121 cm sample to the top of the core, diversity values were consistently higher (H’ > 2.65). Similarly, evenness indices (J’) followed the same pattern, with higher values observed near the base, lower values in the section of low diversity, and higher evenness near the top. These results suggest that the upper and lower sections of the studied downcore exhibit greater homogeneity in terms of the proportional distribution of species and specimens within the samples.

From the Ammonia-Elphidium index (AEI) data, it is possible to notice that the samples from 241 to 111 cm have the highest values, while the base and top of the core have the lowest values. The association of AEI with stress conditions due to lack of oxygen since the genus Ammonia is more tolerant to this condition than Elphidium (and Cribroelphidium)22. This analysis allows us to infer that the base and top of the core corroborate an environment with better oxygenation (oxic) and the range of samples from 241 cm to 111 cm have low oxygenation or even hypoxia.

The most abundant taxa from the base (288 cm) to the top (0 cm) of the core are A. tepida (40.6%) and E. excavatum (8.8%), followed by H. boueana (4.4%), Q. lamarckiana (2.2%), Bolivina spp. (2.0%), Neoeponides spp. (1.9%), Q. venusta (1.7%), Peneroplis planatus (1.5%), Cibicides spp. (1.6%) and Amphistegina spp. (1.4%). The genus Elphidium occurs in all samples, and represents on average 10–20% of the abundance of the assemblages of each core sample, except for the base that reaches up to 30% of abundance. On the other hand, has a relative abundance of < 10% at the base and top of the core, while in the range from 241 to 111 cm, it presents values > 60%.

The composition of the tests along the core is dominated by hyaline forms, except for samples 51 and 41 cm, which are dominated by porcelaneous forms.

The foraminifera assemblage at the base of the core demonstrates co-occurrence of both epifaunal and infaunal life strategies species. The foraminifera assemblage of the sedimentary package 241 –111 cm has a predominantly infaunal strategy (genus Ammonia)15. At the top of the core, the assemblages present a predominant epifaunal species. Species of planktonic foraminifera were also recorded, and are present with a relative abundance of 5% in the samples at the base (288 –251 cm) and the top (11 –2 cm).

Multivariate and biofacies analyzes

Species abundance values diversify according to changes in sedimentary facies and core depth. Therefore, it was possible to divide the core into biofacies based on benthic foraminifera assemblages. The similarity between the samples was analyzed, and calculated by the Bray-Curtis Similarity Index and an NMDS and a cluster analysis were based on this similarity matrix. The clusters showed four distinct biofacies. The biofacies were named using abbreviated forms that represent the most abundant genera and/or species present (Fig. 4).

The EH Biofacies gather samples from the base (288–251 cm), where the dominant species of this group are Elphidium sp. and H. boueana. The other taxa that are frequent in these Biofacies are C. excavatum, Neoeponides sp., Amphistegina sp., Cibicides sp., A. tepida, Pseudononion japonicum, and Elphidium crispum.

The At Biofacies gather samples from 241 to 111 cm, where the dominant species is A. tepida. The species also frequent in this group is E. excavatum.

The AE Biofacies brings together samples from 101 to 41 cm, where the dominant species are A. tepida and C. excavatum. The other taxa that are frequent in these biofacies are Q. venusta, Q. lamarckiana, Cornuspira involvens, Sigmamiliolinella australis, Cibicides fletcheri, P. planatus and Bolivina sp.

The HQ Biofacies gather the top samples (31 –2 cm), where the dominant species are H. boueana and Q. lamarckiana. The other taxa that are frequent in these biofacies are P. planatus, C. excavatum, Bigenerina nodosaria, Nonionoides grateloupii, Rosalina floridana, Q. venusta and Neoeponides sp.

Variation of isotope values

The isotopic values of Elphidium (and some Cribroelphidium) tests, referring to δ18O, exhibit a general variation ranging from − 0.62 to -1.78‰. Samples from the base of the downcore up to 111 cm show values ranging from − 1.08 to -1.78‰. In the range of 90 to 20 cm, the δ18O values demonstrate a greater amplitude, varying from − 0.68 to -1.15‰. At the top of the core, δ18O values are relatively similar, ranging between − 0.62 and − 0.64‰.

The isotopic values of δ13C vary in general between − 3.88 and − 0.02‰. Base values up to 81 cm vary between − 1.57 and − 3.88‰, concentrating lighter values of δ13C. And the values from 71 cm to the top vary between − 0.02 and + 0.09‰.

The results are summarized in Fig. 3.

Discussion

The identified benthic foraminiferal biota exhibited a dominance of individuals belonging to the genera Ammonia and Elphidium, which are commonly associated with mixohaline environments1. The taxa H. boueana, Q. lamarckiana, Bolivina spp., Neoeponides spp., Q. venusta, Peneroplis planatus, Cibicides spp., Amphisteginaspp., and rare planktonic foraminifera formed assemblages representing marine, coastal and continental shelf environments15,23 (see Table 1).

Biofacies EH–mixing processes

In the EH Biofacies, approximately 20% of the identified taxa are epifaunal and are commonly associated with foraminiferal assemblages found in reef environments. For example, the genus Amphistegina spp. thrives in warm waters (typically > 20 °C) with consolidated substrates or gravelly carbonates, often found in areas of the inner shelf and coral reefs. Epifaunal taxa such as Hanzawaia spp., Cibicides spp., and the species Elphidium crispumtypically inhabit sediments with higher sand content and can live on algae15. Furthermore, hyaline forms like Neoeponidesspp. can be found in deeper waters, even in the bathyal regions24.

The dominant taxa of this biofacies is Elphidium spp., which is common in sandy sediments on the inner shelf, as well as Ammonia sp. and Pseudononion japonicum, which may also be common in sandy sediments. The genera Ammonia and Elphidiumare generally more abundant on the inner shelf, in a study carried out by Eichler et al.25 this same distribution pattern was found in the southern portion of the Brazilian continental margin with the species P. japonicum (= Pseudononion atlanticum). The occurence of planktonic foraminifera (~ 5%) also indicates an inner shelf environment23,26,27.

The EH Biofacies shows a variation in mud and sand contents, however, there is an indication of an increase in sand content and a decrease in CaCO3, from the base of the core and the carbonate concretions towards the upper limit of the biofacies. This trend indicates an increase in energy and terrigenous input, while the C/N ratio indicates a marine environment28 and the AEI values point to an environment with well-oxygenated waters22.

The organisms observed in this biofacies could be attributed to an erosive process that occurred on the surface of carbonate concretions in an older (upper Pleistocene) environment. The foraminiferal assemblage indicates a marine environment within a climate range covering from temperate to tropical, characterized by a consolidated substrate and warm waters (> 20ºC) typical of inner shelf or reefs. The presence of secondary carbonate encrustations on the foraminiferal tests, as observed in the SEM images shown in Fig. 5, supports this hypothesis. Hence, it is plausible that a significant portion of the organisms identified in these biofacies represent a paleoenvironment distinct from the present. This is reinforced by the dating obtained along the core, with the base indicating an age of 48.5 kyr BP and the samples associated with this biofacies dating back to approximately 13.2 kyr BP7.

Concerning isotope analyses, in which this biofacies we have only three determined values, the values of the genus Elphidium do not have a clear trend and may be indicative of discontinuous variations in the environment.

Biofacies At–Lagoonal environment during YD

The At Biofacies presented an average of 70% of the specimens of the hyaline species A. tepida, a species that adapts to waters with a wide variation in salinity, such as lagoons and estuaries15. Furthermore, A. tepida is an opportunistic cosmopolitan species, tolerant to environmental changes to which other species do not resist22,29,30,31. In general, the samples from this biofacies shows a continuous occurrence of foraminifera biota with a predominance of typically mixohaline genera, such as Ammonia and Elphidium. Also, the entire biofacies has mud contents, on average, above ~ 80%, which is consistent with the characteristics of the assemblage found15.

Similar observation was made by Vicalvi et al. (1978) at the base of a core collected in the Abrolhos Depression (66.2 m dated at ~ 11.8 cal kyr BP.). The authors found a benthic foraminifera assemblage with around 95% of the specimens consisting of typically mixohaline species (Ammonia parkinsoniana, A. tepida and species of the Elphidiidae family, such as Cribroelphidium sp. and Elphidiumsp.), which is similar to the samples from this biofacies21. The chosen organisms for isotopic analysis (Elphidium) are typically found in shallow water environments, primarily on the continental shelf32, residing within the top 4 cm of sediment33. The results obtained reflect the pore water of the sediment.

In coastal environments influenced by continental inputs, temperature plays a crucial role in the δ18O composition of foraminiferal test, reflecting salinity variations34. The δ18O values observed in the At Biofacies samples indicate lower salinities and higher pore water temperatures within the sediment35. The carbon isotopic composition of foraminiferal tests in coastal waters is also influenced by salinity, with inland waters showing lower δ13C values compared to open sea waters34. It is important to highlight that for these biofacies, the number of available measurements is very low, therefore, a detailed/complete interpretation cannot be proposed.

Additionally, local primary productivity can lead to more positive δ13C values in carbonates formed in surface waters, while oxidation of organic matter in bottom waters results in higher negative δ13C values. The oxidation of terrestrial organic carbon can contribute to lighter δ13C values in the bottom waters, without a corresponding increase in the surface waters. Oxygen consumption due to the oxidation of isotopically lighter organic carbon from local productivity and terrigenous sources can result in hypoxia or anoxia. Negative carbon isotopic values in benthic foraminifera may indicate the occurrence of hypoxia or anoxia, regardless of the source of organic carbon36.

The AEI values increase drastically in this Biofacies, indicating a decrease in sediment oxygenation22, corroborating the isotopic values of δ13C found in foraminifera tests.

Within the At Biofacies two stages are observed concerning the ecological data of the foraminifera, and the sedimentological and geochemical results. The initial interval (between the samples 231–181 cm), according to the indicative limits of the origin of the organic matter defined by Meyers28, the C/N ratio data indicate the presence of plant fragments of predominantly terrestrial origin, that is, the contribution of organic matter from the terrestrial origin is proportionally greater than that from marine origin. Furthermore, the density of benthic foraminifera in this range does not exceed 200 ind./cm³. During this period, the environment probably went through stages of severe hypoxia or drastic decrease in salinity (due to the input of freshwater). Samples 211 cm and 201 cm did not present specimens of foraminifera and coincide with the highest organic matter contents (~ 25%) obtained along the core. This, suggests a more restricted environment with less circulation.

The upper interval of the At Biofacies (between the 170 –110 cm samples) presents signature values of a transitional environment according to the C/N ratio, which corroborates with the decrease of the terrigenous contribution. The sample at 141 cm has a relevant increase in sand content and foraminifera density (3,354 ind./cm³), with an assemblage dominated by A. tepida (> 80%). In addition, values of richness, diversity, CaCO3 and sand contents increase towards the upper limit of this biofacies.

Thus, we can infer that the end of At Biofacies and the beginning of the AE Biofacies mark the shelf drowning process, changing from a transitional environment to a marine environment. More specifically, this moment can be seen with the decrease in the dominance of A. tepida in the 111 cm sample (< 60%) and the increase in the relative abundance of the genera Cibicides, Quinqueloculina, Hanzawaia and Bolivina. The evolution of this Biofacies occurred in an interval dated from ~ 10.841 kyr BP (63.9 m) and ~ 10.681 kyr BP (63.5 m), when there was an almost uniform global sea level rise4.

Biofacies AE–Lagoonal to inner shelf environment-flooding after YD

The AE Biofacies gathers samples from 101 to 41 cm, where the dominant species are A. tepida and E. excavatum. Unlike the previous biofacies, the AEI values decrease (average ~ 40) in this sedimentary package, indicating increased oxygenation of the sediment. δ13C isotopic values follow a trend that indicates increased productivity in the environment, and δ18O values follow a trend that suggests gradual distancing from the continent and higher salinities35. Approximately 37% of the specimens from the AE Biofacies are represented by porcelaneous foraminifera, corroborating an environment with higher energy and increased oxygenation in the sediment15.

The other taxa that are frequent in AE Biofacies are Q. venusta, Q. lamarckiana, Cornuspira involvens, Sigmamiliolinella australis, Cibicides fletcheri, P. planatus, and Bolivinasp. which corroborates the hypothesis of a typically shallow carbonate shelf environment14.

The C/N ratio values indicate a predominantly marine environment from the 101 cm sample to the top of the downcore (AE and HQ Biofacies). And the samples show a gradual increase in CaCO3content, indicating a carbonate environment7. The richness of taxa increases along with the increase in CaCO3 content.

Biofacies HQ–Open marine environment

The HQ Biofacies does not show the genus Ammonia. Species of the genus Ammonia occur in the most marginal marine environments with > 80% mud/silt, from salt marshes and estuaries to subtidal habitats, also in inner shelf environments up to a limit of approximately 50 m15. The disappearance of the genus Ammonia may indicate a sign of a rise in sea level, which has shifted from the coastal marine environment to the open marine environment. The ecological indices point to an environment of high oxygenation that favors the epifaunal genus. The values of carbon and oxygen isotopes follow the same trend as those of the previous biofacies, which may indicate an increase in productivity and a gradual distance from the continent with higher salinities.

The benthic/planktonic foraminifera ratio still represents an inner platform zone with a relative abundance of less than 10% of planktonic foraminifera in the 11 cm and 2 cm samples23.

The average CaCO3 content exceeds 95% in the HQ Biofacies, characterizing a carbonate-dominated sedimentation environment. HQ Biofacies gathers the sedimentary package with the greatest diversity of benthic foraminifera in the core, typical of the Abrolhos carbonate platform37,38,39,40,41,42,43. In general, benthic foraminifera in Abrolhos are represented by coral reef-associated taxa, such as the genera H. boueana, P. planatus, Neoeponides sp. and species Rosalina floridana and Amphistegina radiata, among others, as well as the presence of the specie B. nodosaria, typical of the shelf environment and upper bathyal zone15,24.

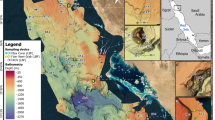

Abrolhos depression environmental evolution post-LGM

Biofacies analysis, together with an age and depth plot allowed the interpretation of the paleoenvironmental evolution of AD (Fig. 6). Correlating the calibrated C14dates from Cetto7with the relative sea-level curves of Abdul et al.44 and Blanchon45, this deposit would indicate a sea level around 65–66 m below the current level at ~ 13.0 kyr BP. According to Lambeck et al.4 it would be around 75 m below the current level. This would indicate that the depression region would already have marine influence after MWP-1 A, possibly setting up an environment with < 1 m of the water column (see the morphological and submersion maps from Cetto7 on Fig. 6B and C).

Previous works7,20,46,47,48 suggest that during the shelf exposure process in the LMG, a karst topography was formed in the ACS. This karst development can be attributed to the erosion and dissolution of carbonate depositional sequences formed during the Pleistocene interglacial periods. Therefore, the observed EH Biofacies develops over a karstic surface that was formed during subaerial exposure in the Late Pleistocene. EH Biofacies has carbonate concretions at 65.85 m dated to ~ 48.55 kyr BP and a wood fragment at 65.75 m dated to ~ 13.27 kyr BP (Fig. 6).With post-LMG transgression and subsequent sea level rise, this karst surface experiences erosion, particularly through the formation of a ravinament surface, influenced by oceanographic processes. The erosion of the carbonate deposit may have introduced reworked foraminifera tests, which are typically associated with a marine environment and do not align with the ~ 13.0 kyr BP dating. This highlights the pioneering nature of evaluating benthic foraminifera assemblages in these sedimentary facies on the karstic surface, contributing to the refinement of existing models proposed for the AD.

Thus, the area of the AD was flooded after MWP 1 A and the first deposit that represent a stillstand during YD period is the At Biofacies. This Biofacies exhibits dates near its lower and upper boundaries of ~ 12.597 cal kyr BP, and ~ 10.841 cal kyr BP, respectively, in a depth range from 63.3 to 63.9 m (Fig. 6). The At biofacies time interval is related to the YD stillstand stage and the onset of MWP 1B4,44,45. The MWP-1B event is considered to be the response of the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets collapse to the rapid warming at the end of the YD. Overall, this event resulted in a sea-level increase of about 14 ± 2 m at a rate of approximately 40 mm/year (~ 11.45–11.10 kyr BP)44.

The YD is a cooling event with a humid climate condition49,50,51. Considering the environment settings at the AD, the dated interval between 12.597 cal kyr BP (65.3 m) and 12.487 cal kyr BP (64.4 m) corresponds to the beginning (~ 12.5 Kyr BP) of the YD (Fig. 6) and the At Biofacies is, sedimentologically, dominated by terrigenous mud. The paleoecological information interpreted from the benthic foraminifera data presented herein indicates an environment that went through stages of severe hypoxia or drastic decrease in salinity (due to the supply of freshwater), as an environment with a very restricted marine influence, low circulation, like a confined lagoon, corroborating previous interpretations of Cetto et al.20, Cetto7 and Bastos et al.8.

Within the At Biofacies, a initial shift in environmental conditions takes place at the 141 cm sample, which corresponds to a depth of 64.4 m, with an approximate dating of 12.487 cal kyr BP (Fig. 6). This shift is marked by a relevant increase in the foraminifera density of a single species, A. tepida(> 80%), indicating possible marine incursion events favoring the reproduction of the species at first15,22,29,30,31. Moreover, towards the upper limit of At Biofacies (10.7 cal kyr BP), the foraminifera biota indicates an estuarine environment, with greater circulation. This shift in the foraminifera assemblage composition correlates with the MWP 1B onset, which triggered the total flooding of AD7,18,20.

From ~ 10.7 cal kyr BP onward, an increase in CaCO3 content is observed and the AD started to show foraminifera assemblages typical of a marine environment, mainly of a shallow carbonate platform. This is marked by the AE Biofacies. This biofacies defines the entire shelf flooding and the onset of a carbonate dominated sedimentation. That coincides with the abandonment of the reentrant conformation of AD, that had occurred when sea level covered the prominent marginal banks around this feature, around the ~ 40 m quota7,20.

The disappearance of the genus Ammonia and the appearance of planktonic foraminifera in HQ Biofacies indicates a deeper environment, with depths > 50 m. The biofacies changes occurs around 30–40 cm (~ 63.3 m), which corresponds to two radiocarbon dates: 7.2–6.5 cal kyr BP (63.4 m) and 6.8–6.2 cal kyr BP (63.3 m) (Fig. 6). This change in the foraminifera assemblage and biofacies could be the result of a steady sea-level rise, but could also be an evidence of rapid increase in sea-level rise rates. In this case, the ages are very close to another meltwater pulse proposed by Blanchon45, which is the MWP 1 C dated at ~ 8.0-7.6 kyr BP, triggering a sea-level rise of 5–9 m, at a rate of ~ 13–23 mm/yr. In northeastern Brazil, a rapid sea level rise of up to ~ 6.1 mm/year, between 8.3 and 7.0 cal kyr BP was also observed52. In the Abrolhos Shelf, other works have also suggested that the occurrence of drowned reefs at 20 m deep was the result of a rapid sea-level rise, which would correspond to MWP 1 C53,54.

The summarized data from the AD core and its biofacies related to the paleoclimatic and paleoceanographic events are represented by the Fig. 6.

(A) Relative Sea Level Oscillation Curve based on compiled data from Lambeck et al.4, Abdul et al.44, and Blanchon45; calibrated present-day dating from the core obtained by Cetto et al.7, as well as core T_4160 conducted by Vicalvi et al.21; highlighting the key global paleoceanographic events of this period and the Biofacies. (B and C) Maps estimate the Post-LGM submersion phases of AD during upper Pleistocene and Holocene eustatic events based on the present bottom morphology. (B) Drowning of Besnard Channel during MWP-1 A and instalation of a lagoon during the Younger Dryas. (C) Shift from a lagoon to an embayment during MWP-1B. Maps were produced by co-authors using ArcGIS Pro 3.2.0 using the same dataset published in Cetto7and Cetto et al.20.

Conclusion

The paleoenvironmental evolution of AD based on the distribution of benthic foraminifera in the present study contributed to the refinement of pre-existing models. This is due to the taxonomic level reached, which allowed the performance of statistical analyzes (such as NMDS, for example) to confirm the robustness of the foraminifera assemblages found and their characteristics as biofacies, the ecology of the identified taxa (genus and species level) and indices ecological data related to paleoceanographic and paleoclimate events during the Quaternary.

The base of the downcore points to the presence of carbonate concretions that can compose a karst ravine surface. The deposition of EH Biofacies occurs on this surface and points to the marine influence and the beginning of the formation of the paleolagoon around 13.0 kyr BP.

The formation of DA occurs during the YD and it presents two distinct phases in terms of sedimentation and circulation in the lagoon environment. At first, between 12.8 and 12.5 cal kyr BP. the lagoon is characteristically confined with less circulation and from around 12.5 kyr forwards there is an increase in the lagoon circulation marked by an increase in the density, richness, and diversity of benthic foraminifera.

The end of the YD is marked by a significant change in biofacies, where foraminifera assemblages indicate to a shallow marine environment (AE Biofacies), which is corroborated by all sedimentological and geochemical proxies. This paleoenvironmental change is associated with MWP-1B.

With the continuous rise in sea-level, the setting becomes to open marine environment, but there is still a change around 8.0 kyr BP which definitively marks the presence of organisms typical of the outer shelf, that is, depths greater than 50 m, as a result of the MWP-1 C.

Methods

The foraminiferal analyses herein were integrated with the set of sedimentological data (granulometry and composition), dating and geochemical composition of the organic matter presented by Cetto7. The sedimentary core (DA03A_5B) was collected by the author in the AD using a piston corer (Fig. 1, 24 S UTM 533781.04/7925606.24), planned using high resolution seismic data. The downcore length is 2.90 m and the core was collected at 63 m water depth.

Total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (C/N ratio) content

Total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (C/N ratio) content, analyzed in an Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS, Thermo Scientific ® Delta V system) coupled to an Elemental Analyzer (CHN, Thermo Scientific ® Flash EA1112 system) by dry combustion;

Chronology

Calibrated ages (years BP) of the core by the 14 C isotope dating method (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry - AMS) carried out at the Applied Isotope Studies Laboratory of the University of Georgia - USA, comprising bivalve mollusc shells without signs of reworking, wood fragments and calcareous concretions.

The radiocarbon ages were checked using the Calib 8.2 program55and reported in years BP (before 1950) in the 2σ confidence interval. The Marine20 curve56was used for the limestone samples, and the SH20 curve (South Hemisphere, Hogg et al.57) was used for the plant samples. For marine samples, the effect of the oceanic rectangle was considered according to the Marine20 curve, obtaining locally ΔR = -41 ± 109, calculated from the average of the 4 points closest to the practice area, comprising values reported by Oliveira et al.58, Alves et al.59 and Eastoe60. The same criteria were adopted for the recalibration of past dating data obtained by Vicalvi et al.21.

Sedimentological analyses

In the laboratory, the sediment downcore was opened lengthwise, measured, photographed, described, and sliced every 1 cm, and the subsamples were frozen. The faciological and textural characterization of the sediment was carried out at intervals of 5 cm from the lyophilized sediment, with representative aliquots destined for each type of sedimentological analysis. The granulometric classification of the coarse fraction of the sediment (sand + gravel) was obtained through the wet sieving method61in intervals of 0.5 phi. The content of the muddy fraction was obtained from the difference between the dry weight of the total aliquot and the sum of the contents accumulated in the set of sieves. The mean diameters were obtained from the Folk & Ward62method using the Gradistat software by Blott & Pye63, adopting the nominal classification proposed by Wentworth64. Textureally, the sediments were classified according to Folk65. The CaCO3content was evaluated separately in the coarse (gravel + sand) and fine (mud) fractions of the samples through the dissolution method with 10% HCl66. The total organic matter content (TOC) was obtained for an aliquot of ~ 1 g of the sample through the calcination method of the material in a muffle at 550ºC for 4 h67.

Benthic foraminiferal analysis

The data from the benthic foraminiferal assemblage came from 33 samples, taken downcore between 2.88 m and 0 m. A standardized volume of 20 cm3 of sediment was selected every 10 cm of the DA03A_5B core for foraminifera analysis. The samples were dried in an oven at 40 °C, weighed, soaked in water, washed under tap water through a 63 μm sieve, dried, and weighed again. Processed samples were split from 63 μm size fraction with a microsplitter to obtain at least 300 specimens of benthic foraminifera per sample.

All benthic foraminifera were picked up and included in the assemblage counts. A total of 85 taxa were identified, with 43 taxa contributing significantly to the total population (with relative abundances of more than 1% in at least two samples). The relative abundance of these 43 taxa was analyzed using Q-mode Varimax factor analysis, using the STATISTICA software package. The number of benthic foraminifera (BFN = number of benthic foraminifera/gram dry sediment) was calculated for each sample, as well as the percentage of agglutinated, porcelaneous, and calcareous hyaline tests. The microhabitat preference (epifaunal vs. infaunal) was recorded, based on specialized bibliography15.

Ammonia-elphidium index (AEI)

The Ammonia-Elphidium Index (AEI) was calculated to estimate the hypoxia levels throughout the study area. Both genera are resistant to hypoxic conditions, but Ammonia shows a greater resistance than Elphidium. This index has been used in the literature to study regions affected by hypoxia due to the large contribution of organic matter22.

The index is given by:

Where: NA = sum of Ammonia spp. relative abundances. NE = sum of Elphidium spp. and Cribroelphidium spp. relative abundances.

Stable isotope

Isotope analysis of δ18O oxygen and δ13C carbon in benthic foraminifera were carried out at the Stable Isotopes Laboratory (LES)/Center for Research in Geochronology and Isotopic Geochemistry (CPGeo) at the Institute of Geosciences of the University of São Paulo (IGc - USP).

For the analysis, approximately 30 specimens of the genus Elphidium (mainly E. excavatum) were separated from each sample. The foraminifera specimens were placed in 12 mL Exetainer® vials, capped with rubber septa. The flasks were evacuated with helium gas for 15 min. Then an excess of 100% phosphoric acid was dripped at 70 ° C. The CO2 resulting from the reaction with the acid was purified online in the gas-chromatographic column of the Finnigan Gas Bench II preparation module and analyzed with the Thermo Finnigan Delta V mass spectrometer (under a continuous flow of He). The raw δ18O and δ13C data were corrected using a set of three internal calcite standards, calibrated against the international standard NBS 19. The corrected delta values were expressed in parts per thousand, against the international reference Vienna PeeDee Belemnite (V-PDB).

Defined by the equation:

Where: X = 13C or 18O. R sample = corresponding ratio of 13C/12C or 18O/16O. R standard = corresponding to the V-PDB reference.

Data availability

Data is provided within this manuscript and supplementary material. Any other data will be available upon request.

References

Ribó, M., Goodwin, I. D., O’Brien, P. & Mortlock, T. Shelf sand supply determined by glacial-age sea-level modes, submerged coastlines and wave climate. Sci. Rep.10, 1, 462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57049-8 (2020).

Fairbanks, R. G. A. 17,000-year glacio-eustatic sea level record: influence of glacial melting rates on the younger Dryas event and deep-ocean circulation. Nature. 342, 6250, 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/342637a0 (1989).

Rabineau, M. et al. Paleo sea levels reconsidered from direct observation of paleoshoreline position during glacial Maxima (for the last 500,000 year). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.252 (1–2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.09.033 (2006).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.111 (43), 15296–15303. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411762111 (2014).

Vacchi, M. et al. Variability of the millennial sea-level histories along the western African coasts since the Last Glacial Maximum. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. EGU21-3019. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-3019 (2021).

Curray, J. R. Transgression and regression. Papers in marine geology. Shepard commemorate volume, Macmillan, 175–203. (1964).

Cetto, P. H. Registros estratigráficos e morfológicos da variabilidade eustática e paleoambiental pósúltimo máximo glacial na plataforma continental leste-sudeste do brasil. Programa de Pós Graduação em Oceanografia Ambiental, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Brasil. (2022).

Bastos, A. C. et al. Sedimentological and morphological evidences of meltwater pulse 1B in the Southwestern Atlantic Margin. Mar. Geol.450, 106850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2022.106850 (2022).

Sen Gupta, B. K. Modern Foraminifera. (Ed.) Kluwer Academic Publishers (1999).

Boltovskoy, E., Scott, D. B. & Medioli, F. S. Morphological variations of benthic foraminiferal tests in response to changes in ecological parameters: a review. J. Paleontol.65 (2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000020394 (1991).

Cushman, J. A. Foraminifera: their classification and economic use (No. 1). Cushman Laboratory for Foraminiferal Research (1928).

Boltovskoy, E., Giussani, G., Watanabe, S. & Wright, R. C. (eds) Atlas of Benthic Shelf Foraminifera of the Southwest Atlantic (Springer Nature, 1980).

Schönfeld, J. Benthic foraminifera and pore-water oxygen profiles: a re-assessment of species boundary conditions at the western Iberian margin. J. Foraminifer. Res.31 (2), 86–107. https://doi.org/10.2113/0310086 (2001).

Armstrong, H., & Brasier, M. Microfossils. John Wiley & Sons (2013).

Murray, J. W. Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Sousa, S. H. D. M. Foraminíferos planctônicos e bentônicos: da plataforma e talude continental do Atlântico Sudoeste, entre 19°-33° S. EDUSP (2012).

Hyams-Kaphzan, O., Almogi-Labin, A., Sivan, D. & Benjamini, C. Benthic foraminifera assemblage change along the southeastern Mediterranean inner shelf due to fall-off of Nile-derived siliciclastics. Neues Jahrbuch Fur Geologie Und Palaontologie-Abhandlungen. 248 (3), 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2008/0248-0315 (2008).

Green, A. N., Cooper, J. A. G. & Salzmann, L. Geomorphic and stratigraphic signals of postglacial meltwater pulses on continental shelves. Geology. 42 (2), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1130/G35052.1 (2014).

Lebrec, U., Riera, R., Paumard, V., O’Leary, M. J. & Lang, S. C. Morphology and distribution of submerged palaeoshorelines: insights from the North West Shelf of Australia. Earth Sci. Rev.224, 103864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103864 (2022).

Cetto, P. H., Bastos, A. C. & Ianniruberto, M. Morphological evidences of eustatic events in the last 14,000 years in a far-field site, East-Southeast Brazilian continental shelf. Mar. Geol.442, 106659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2021.106659 (2021).

Vicalvi, M. A., Costa, M. P. A. & Kowsmann, R. O. Depressão De Abrolhos: uma paleolaguna holocênica na plataforma continental leste brasileira. Bol. Tec. Petrobrás. 21 (4), 279–286 (1978).

Sen Gupta, B. K., Turner, E., Rabalais, N. N. & R., & Seasonal oxygen depletion in continental-shelf waters of Louisiana: historical record of benthic foraminifers. Geology. 24 (3), 227–230 (1996).

J Culver, S. New foraminiferal depth zonation of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Palaios. 69–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/3514545 (1988).

Holbourn, A., Henderson, A. S., MacLeod, N. & MacLeod, N. Atlas of Benthic ForaminiferaVol. 654 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Eichler, P. P. B., Rodrigues, A. R., Eichler, B. B., Braga, E. D. S. & Campos, E. J. D. tracing latitudinal gradient, river discharge and water masses along the subtropical south American coast using benthic foraminifera assemblages. Brazilian J. Biology. 72, 723–759. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842012000400010 (2012).

Hayward, B. W., Hollis, C. J. & Grenfell, H. R. Recent Elphidiidae (Foraminiferida) of the south-west Pacific and Fossil Elphidiidae of New Zealand (Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences, 1997).

De Rijk, S., Troelstra, S. R. & Rohling, E. J. Benthic foraminiferal distribution in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Foraminifer. Res.29 (2), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.29.2.93 (1999).

Meyers, P. A. Preservation of elemental and isotopic source identification of sedimentary organic matter. Chem. Geol.114 (3–4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90059-0 (1994).

Yanko, V., Kronfeld, J. & Flexer, A. Response of benthic foraminifera to various pollution sources: implications for pollution monitoring. J. Foraminifer. Res.24 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.24.1.1 (1994).

Alve, E. Benthic foraminiferal responses to estuarine pollution; a review. J. Foraminifer. Res.25 (3), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.25.3.190 (1995).

Culver, S. J. & Buzas, M. A. The effects of anthropogenic habitat disturbance, habitat destruction, and global warming on shallow marine benthic foraminifera. J. Foraminifer. Res.25 (3), 204–211. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.25.3.204 (1995).

Miller, A. A., Scott, D. B. & Medioli, F. S. Elphidium excavatum (Terquem); ecophenotypic versus subspecific variation. J. Foraminifer. Res.12 (2), 116–144. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.12.2.116 (1982).

Buzas, M. A. The distribution and abundance of foraminifera in Long Island Sound. Smithson. Miscellaneous Collections. 149 (1), 1–88 (1965).

Anderson, T. F. & Arthur, M. A. Stable isotopes of oxygen and carbon and their application to sedimentologic and paleoenvironmental problems. SEPM Soc. Sediment. Geol.https://doi.org/10.2110/scn.83.01.0000 (1983).

Thomas, E., Gapotchenko, T., Varekamp, J. C., Mecray, E. L. & Ten Brink, M. B. Benthic foraminifera and environmental changes in Long Island Sound. J. Coastal Res.16 (3), 641–655. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4300076 (2000).

McCorkle, D. C. & Emerson, S. R. The relationship between pore water carbon isotopic composition and bottom water oxygen concentration. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 52 (5), 1169–1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(88)90270-0 (1988).

Oliveira-Silva, P., Barbosa, C. F. & Soares-Gomes, A. Distribution of macrobenthic foraminifera on Brazilian Continental margin between 18ºS–23ºS. Brazilian J. Geol.35 (2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.25249/0375-7536.2005352209216 (2005).

De Araújo, H. A. B. & De Machado, J. Benthic foraminifera associated with the South Bahia Coral Reefs, Brazil. J. Foraminifer. Res.38 (1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.38.1.23 (2008).

Barbosa, C. F., de Freitas Prazeres, M., Ferreira, B. P. & Seoane, J. C. S. Foraminiferal assemblage and reef check census in coral reef health monitoring of East Brazilian margin. Mar. Micropaleontol.73 (1–2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2009.07.002 (2009).

de Jesus Machado, A. & de Araújo, H. A. B. Relação entre a microfauna de foraminíferos e a granulometria do sedimento do Complexo Recifal De Abrolhos, Bahia, a partir de análises multivariadas. Brazilian J. Geol.42 (3), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.25249/0375-7536.2012423547562 (2012).

Barbosa, C. F. et al. Foraminifer-based coral reef health assessment for southwestern Atlantic offshore archipelagos, Brazil. J. Foraminifer. Res.42 (2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.42.2.169 (2012).

Oliveira-Silva, P. et al. Sedimentary geochemistry and foraminiferal assemblages in coral reef assessment of Abrolhos, Southwest Atlantic. Mar. Micropaleontol.94, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2012.03.005 (2012).

Almeida, C. M. et al. Palaeoecology of a 3-kyr biosedimentary record of a coral reef-supporting carbonate shelf. Cont. Shelf Res.70, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2013.05.012 (2013).

Abdul, N. A., Mortlock, R. A., Wright, J. D. & Fairbanks, R. G. Younger Dryas sea level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados reef crest coral Acropora palmata. Paleoceanography. 31 (2), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015PA002847 (2016).

Blanchon, P. Back-stepping. Encyclopedia Mod. Coral Reefs:Structure, form and process, 77-84. (2011).

Bastos, A. C. et al. Shelf morphology as an indicator of sedimentary regimes: a synthesis from a mixed siliciclastic–carbonate shelf on the eastern Brazilian margin. J. S. Am. Earth Sci.63, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.07.003 (2015).

Bastos, A. C. et al. Origin and sedimentary evolution of sinkholes (buracas) in the Abrolhos continental shelf, Brazil. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.462, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.09.009 (2016).

D’Agostini, D. P., Bastos, A. C. & Dos Reis, A. T. The modern mixed carbonate–siliciclastic Abrolhos shelf: implications for a mixed depositional model. J. Sediment. Res.85 (2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2015.08 (2015).

Novello, V. F. et al. A high-resolution history of the South American Monsoon from last glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 44267. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44267 (2017).

Bouimetarhan, I. et al. Intermittent development of forest corridors in northeastern Brazil during the last deglaciation: climatic and ecologic evidence. Q. Sci. Rev.192, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.05.026 (2018).

Piacsek, P. et al. Reconstruction of vegetation and low latitude ocean-atmosphere dynamics of the past 130 kyr, based on south American montane pollen types. Glob. Planet Change. 201, 103477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2021.103477 (2021).

Boski, T. et al. Sea-level rise since 8.2 ka recorded in the sediments of the potengi–Jundiai Estuary, NE Brasil. Mar. Geol.365, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.04.003 (2015).

Vieira, F. V., Bastos, A. C. & Quaresma, V. S. Submerged reef and inter-reef morphology in the Western South Atlantic, Abrolhos Shelf (Brazil). Geomorphology. 442, 108917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2023.108917 (2023).

Cetto, P. H., Bastos, A. C., Menandro, P. S. & Webster J.MMWP-1 C and reef drowning: morphological evidence along the eastern Brazilian margin. Mar. Geol.469, 107243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2024.107243 (2024).

Stuiver, M., Reimer, P. J. & Reimer, R. W. CALIB 8.2 [WWW program] at http://calib.org, accessed 2021-6-6. (2021).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20 - the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon. 62 (4), 779–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.68 (2020).

Hogg, A. G. et al. SHCal20 Southern Hemisphere calibration, 0–55,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon. 62 (4), 759–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.59 (2020).

Oliveira, M. I. et al. Marine Reservoir corrections for the Brazilian Northern Coast using modern corals. Radiocarbon. 61 (2), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2018.145 (2019).

Alves, E. et al. Radiocarbon reservoir corrections on the Brazilian coast from pre-bomb marine shells. Quaternary Geochnology. 29, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.05.006 (2015).

Eastoe, C. J., Fish, S. & Fish, P. Reservoir corrections for marine samples from the South Atlantic coast, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Radiocarbon. 44 (1), 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033822200064742 (2002).

Tucker, M. E. Techniques in Sedimentology (Blackwells, 1988).

Folk, R. L. & Ward, W. C. Brazos River bar: a study in the significance of grain size parameters. J. Sediment. Res.27 (1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1306/74D70646-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D (1957).

Blott, S., Pye, K. & GRADISTAT A grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth. Surf. Proc. Land.26, 1237–1248. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.261 (2001).

Wentworth, C. K. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J. Geol.30 (5), 377–392 (1922). https://www.jstor.org/stable/30063207

Folk, R. L. The distinction between grain size and Mineral Composition in Sedimentary-Rock nomenclature. J. Geol.62 (4), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1086/626171 (1954).

Gross, M. G. Carbon Determination. In: Carver, R. E. Procedures in Sedimentary Petrology. Wiley Interscience, New York. (1971).

Mook, D. H. & Hoskin, C. M. Organic determination by ignition: caution advised. Estuar. Coastal. Shelf Sci.15 (6), 697–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7714(82)90080-4 (1982).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) for funding the IODP-Brasil project, and also to the Espirito Santo State Research Foundation for funding the PRONEX-GEOMAR project, enabling sample collection, and covering analysis costs. P.H. Cetto has a post-doc scholarship provided by PROFIX-FAPES grant. Special thanks to the Graduate Program in Environmental Oceanography at UFES (PPGOAm) for supporting the first author’s master’s degree research. The support of LUCCAR at UFES, funded by the MCT/FINEP/CT-INFRA – PROINFRA 01/2006 grant, and the assistance of Tadeu Zanardo in facilitating the SEM images are acknowledged. The authors appreciate the contributions of the Laboratory CPGeo at IGC-USP and Prof. Christian Millo (IO-USP) for conducting isotope analyses. Special thanks to Fabiana K. de Almeida for her valuable guidance and support throughout the research. We also extend our acknowledgments to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and discussion of the study. Material preparation and data collection were performed by P.H.C. and A.G.R. Geochemical analysis and grain size measurements were performed by P.H.C. Data analysis was performed by A.G.R., A.R.R., and P.H.C. Formal analysis and conceptualization of this manuscript were made by A.C.B., A.R.R., and A.G.R. A.C.B. acted as supervisor and grant coordinator. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruschi, A.G., Rodrigues, A.R., Cetto, P.H. et al. Pleistocene to early Holocene paleoenvironmental evolution of the Abrolhos depression (Brazil) based on benthic foraminifera. Sci Rep 14, 24443 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75223-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75223-5