Abstract

The relationship between magnesium deficiency and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) remains unclear. This study aimed to examine the association between the magnesium depletion score (MDS) and the risk of MASLD, as well as explore potential underlying mechanisms. Data from 12,024 participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2018 were analyzed. MDS was calculated based on the use of diuretics and proton pump inhibitors, kidney function, and alcohol consumption. MASLD was defined using the fatty liver index. Logistic regression, restricted cubic spline analysis, and mediation analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between MDS and MASLD and to identify potential mediators. A higher MDS was significantly associated with an increased risk of MASLD (OR = 2.00, 95% CI [1.47, 2.74] for MDS 3 vs. 0). A dose-response relationship between MDS and MASLD risk was observed. Neutrophils, albumin, and white blood cells partially were identified as partial mediators of the association, with albumin exhibiting the highest mediating effect (14.05%). Elevated MDS is significantly associated with an increased risk of MASLD in U.S. adults. Inflammation and albumin may serve as potential mediators of this relationship. These findings underscore the importance of addressing magnesium deficiency in the prevention and management of MASLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a prevalent chronic liver disorder characterized by excessive fat accumulation in hepatocytes and is closely associated with metabolic dysfunction1. In recent years, the rising prevalence of NAFLD has transformed it into a significant global public health concern2. To more accurately reflect the metabolic characteristics of NAFLD, international expert consensus proposed a new definition and diagnostic criteria under the term “metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease” (MASLD)3.

Magnesium, an essential trace element, playing a critical role in over 300 enzymatic reactions and physiological processes within the human body. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a correlation between low magnesium intake and metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes4. Furthermore, animal studies have found that magnesium deficiency may induce hepatic steatosis and inflammation5. Mechanistically, magnesium is essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis, reducing inflammation, and exerting antioxidant effects. By inhibiting the production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), magnesium mitigates oxidative stress, a major contributor to the pathogenesis of MASLD. Magnesium deficiency may exacerbate oxidative damage in the liver, elevate inflammatory cytokine levels, and harm hepatocytes6; Furthermore, low magnesium levels are associated with impaired glucose and fat metabolism, promoting fat accumulation in the liver, and contributing to insulin resistance, a primary driver of MASLD7. Magnesium deficiency may lead to excessive fatty acids accumulation, worsening hepatic steatosis and accelerating the progression of MASLD8. While previous cross-sectional studies have reported an inverse relationship between serum magnesium levels and the incidence of NAFLD9,10, no studies to date have explored the association between magnesium levels and the incidence of MASLD.

The magnesium depletion score (MDS) is a novel metric designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of magnesium status in the body. By incorporating variables such as the use of diuretics and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), kidney function, and alcohol consumption, MDS offers a more holistic reflection of magnesium levels11. Previous studies have demonstrated a link between MDS and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis12,13, but no studies have yet examined the relationship between MDS and MASLD.

Magnesium deficiency has been shown to activate the innate immune response and increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines14, Additionally, magnesium plays a crucial role in protein synthesis15. Common biomarkers such as neutrophils, white blood cells (WBC), and albumin are often used to assess inflammation and nutritional status. Previous studies have found that neutrophils were associated with the severity of NAFLD16, elevated WBC count was a risk factor for NAFLD17, and decreased albumin levels suggested a poor prognosis of NAFLD18. However, the potential roles of these indicators in the relationship between MDS and MASLD have not been fully elucidated.

This study, therefore, aims to utilize data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to explore the relationship between MDS and the risk of MASLD, while also exploring the potential mediating effects of neutrophils, WBC, and albumin. The findings are expected to offer new insights and evidence for the prevention and treatment of MASLD.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

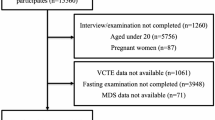

The NHANES is a population-based, cross-sectional survey designed to collect data on the health and nutrition of the U.S. household population. The project began in the early 1960s and is undertaken every two years, visiting 15 counties in the United States with a complicated, multistage, probability sampling method to select a nationally representative sample of around 5,000 individuals. The NHANES website collected information regarding the research design, interviews, demographics, dietary assessment, physical examination, and laboratory data design (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm ). This NHANES study was approved by the NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) Ethics Review Board. Informed consent forms were signed by participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Data for 70,190 participants from NHANES cycles 2005–2018 were initially included. Participants lacking MASLD diagnostic information (n = 55,090) or for whom MDS could not be calculated (n = 781) were excluded. Additionally, participants with missing covariate values (n = 2,295) were further excluded. Ultimately, the final analysis included 12,023 individuals, consisting of 6,219 females and 5,804 males (Fig. 1).

Definition of MASLD

The initial stage of MASLD is characterized by abnormal accumulation of fat in liver tissue. While liver biopsy has historically been considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing MASLD and assessing its severity, the limitations of histological staging, particularly in evaluating fibrosis, have restricted its widespread use in MASLD management19. Noninvasive methods, such as serum biomarker testing and imaging techniques like vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) are now more commonly used to evaluate hepatic steatosis20. The fatty Liver Index (FLI), developed by CE Ruhl et al., has been validated in various studies and shown to exhibit good sensitivity and specificity21,22,23. In large-scale epidemiologic studies, FLI is often preferred over imaging due to its convenience.

In this study, MASLD status was primarily assessed using the FLI score. An FLI ≥ 30 demonstrated a sensitivity of 71.2% for diagnosing MASLD, while an FLI ≥ 60 had a positive predictive value of 69.7% 24. To maximize diagnostic sensitivity and include as large a population as possible, a cut-off value of 30 was used for MASLD diagnosis25.

The specific calculation formula for FLI was as follows:

MASLD was defined as FLI ≥ 30, and excluded other liver diseases associated with the aforementioned factors including: (1) excessive alcohol use; (2) hepatitis B/C virus infection; (3) pharmacological agents associated with steatosis (e.g.: amiodarone, methotrexate, tamoxifen, aspirin, ibuprofen, nrtis (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors), protease inhibitors, valproic acid, carbamazepine, fluorouracil, irinotecan, glucocorticoids); (4) iron overload.

Calculation of the magnesium depletion score

Magnesium depletion was assessed using the MDS, which ranges from 0 to 5. The MDS was calculated by summing the points assigned for four factors: (1) diuretic use (current use for 1 point), (2) proton pump inhibitors (PPI) use (current use for 1 point), (3) kidney function [60 mL/ (min·1.73 m2) ≤ estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 90 mL/(min · 1.73 m2) for 1 point; eGFR < 60 mL/(min·1.73 m2) for 2 points], and (4) alcohol drinking (heavy drinker for 1 point). In the NHANES, current use of diuretics and PPIs was defined as self-reported use over the past 30 days. Heavy drinkers were defined as > 1 drink/d for women and > 2 drinks/d for men26. The Food Patterns Equivalents Database defines alcoholic drinks as beers, wines, distilled spirits (such as brandy, gin, rum, vodka, and whiskey), cordials, and liqueurs. A standard drink was defined as a drink with 14 g (0.6 fluid ounces) of ethanol27.

Covariates

In addition, demographic and serologic indicators were included in the analysis, such as age, sex, race, education, poverty status, marital status, smoking status, white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil count, and albumin levels. NHANES collects data via questionnaires and examinations on people’s personal information, lifestyles, and physical conditions of health. Education level was categorized as “lower than high school”, “high school” and “higher than high school”. Ethnicity was classified into “Mexican American”, “Non-Hispanic Black”, “Non-Hispanic White”, “other Hispanic” and “other race”. Marital was divided into “Divorced”, “Living with partner”, “Married”, “Never married”, “Separated”, and “Widowed”.

Statistical analyses

Given that the NHANES used a complicated, multistage probability sampling methodology to choose representative individuals, sample weights were applied in all analyses to generate nationally representative estimates. Clinical information consists of continuous variables and categorical variables. Continuous variables with normal distributions were provided as mean (interquartile range [Standard Deviation, SD]); categorical variables were presented as percentages and standard error (SE). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used as the normality test. Independent t tests, Welch t tests, and White non-parametric t tests were used for continuous variables. Pearson’s X2 test and Fisher’s exact test of independence were used to compare the proportions of dichotomous variables.

We constructed multivariate logistic regression models to analyze the correlation between MDS and MASLD based on clinical experience and with reference to relevant literature. Multivariable model was adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and smoking, and an additional model was adjusted for BMI (≤ 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–25 kg/m2, > 25 kg/m2) based on multivariable model. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was conducted to characterize dose-response relation-ships. Considering the potential interactions between WBC, neutrophils, albumin and MASLD, we conducted a causal mediation analysis to obtain a rationalization of the causal assumptions between the MDS and MASLD. Subgroup and multiplicative interaction tests were conducted according to sex, age, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and smoking.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Survey package in R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Result

Basic characteristic of participants

A total of 12,024 participants were included in the study (Fig. 1). As shown in Table 1, in the overall population, there was a higher percentage of non-Hispanic White ethnicity, and the majority of participants received a higher than high school education. The proportion of MASLD and non-MASLD patients with an MDS of 0 was 36.26% and 47.05%, respectively, and the proportion of patients with an MDS of 5 was the least, at 0.01% and 0.02%, respectively. Compared with non-MASLD participants, MASLD patients had a higher proportion of males, senior age (≥ 65years), lower WBC and albumin, and higher Neutrophils (all p < 0.001).

The association between the MDS and MASLD

Table 2 shows the relationship between MDS and MASLD. In the univariable model, elevated MDS were positively associated with the risk of MASLD, with patients with MDS of 1, 2, 3, and 4 having a 1.25, 1.97, 3.19, and 2.40 times risk of MASLD compared to those with MDS of 0, respectively (all p ≤ 0.001). In the multivariable model, adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio, and smoking, MDS remained associated with MASLD risk, though the strength of the association was slightly reduced. When further adjusted for BMI, MDS continued to show a positive correlation with MASLD (MDS = 2: OR = 1.41, 95% CI [1.13, 1.77], p = 0.07; MDS = 3: OR = 2.00, 95% CI [1.47, 2.74], p < 0.001). Notably, in both the univariable and multivariable models, no statistically significant association was observed between an MDS of 5 and MASLD risk (Table 2).

To further clarify the dose-response relationship between MDS and MASLD, we constructed a RCS model. MDS were positively associated with MASLD risk, with the highest risk observed at an MDS of 3 when no covariates were adjusted (p-overall < 0.001, p-non-linear = 0.035) (Fig. 2A). In the multivariable model, increased MDS showed a linear relationship with MASLD risk (p-overall < 0.001, p-nonlinear = 0.193) (Fig. 2B).

RCS model between MDS and the risk of MASLD. (A) was unadjusted; (B) was adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and smoking, Abbreviations: RCS, Restricted cubic spline; MDS, magnesium depletion score; MASLD, Metabolic Dysfunction associated Steatotic Liver Disease; OR, Odds ratio.

Analysis of potential causal mediators between MDS and MASLD

We further analyzed potential causal mediators of MDS and MASLD. In Univariable and multivariable logistics regression models, elevated neutrophils and WBC were associated with an increased MASLD risk, whereas elevated albumin was a protective factor for MASLD (Table 3).

Further mediation analyses were performed to assess the role of neutrophils, albumin, and WBC in association with MDS and MASLD. Neutrophils, albumin, and WBC can all mediate the association between MDS and MASLD, with albumin mediating the highest proportion of the association (14.05%), while neutrophils and WBC had a mediating effect of 12.27% and 12.44%, respectively (Fig. 3).

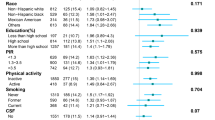

Subgroup and interaction analysis between MDS and MASLD

In subgroup analyses, elevated MDS remained consistently associated with the risk of MASLD, and this result remained stable across age, sex, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio, and smoking. However, there was no statistically significant association observed between MDS and the risk of MASLD in patients who were currently smoking (Fig. 4).

Interaction analyses showed an interaction between age and MDS, with a 1-point increase in MDS associated with a 12% increased risk of developing MASLD among participants aged ≥ 65 years (OR = 1.12, 95%CI [1.02, 1.22], p = 0.0196); Among participants aged < 65 years, patients with elevated MDS have higher risk of MASLD (OR = 1.34, 95%CI [1.22, 1.49], p < 0.0001). No interaction of MDS with gender, race, education, income was observed (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative study of the U.S. adult population, it was found that higher MDS were significantly associated with an increased risk of MASLD. Compared to participants with an MDS of 0, those with MDS of 1, 2, 3, and 4 had a 1.19-, 1.63-, 2.33-, and 1.79-fold higher risk of MASLD, respectively. In a multivariable model, when further adjusted for BMI, a positive trend can be seen despite the decline in the correlation between MDS and MASLD, which might be attributed to data bias, as the small number of participants with MDS scores of 4 and 5 resulted in a lack of statistical significance. The restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a linear dose-response relationship between MDS and MASLD risk (p-nonlinear = 0.13). Mediation analyses showed that neutrophils, albumin, and WBC partially mediated the association between MDS and MASLD, with albumin having the highest mediating effect (14.05%). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the positive association between MDS and MASLD remained consistent across age, sex, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio, and smoking status, with the exception of current smokers. Additionally, a significant interaction was observed between age and MDS (p-interaction = 0.03), with a 1-point increase in MDS associated with a 12% and 34% higher risk of MASLD among participants aged ≥ 65 years and < 65 years, respectively.

Our findings are consistent with previous epidemiological studies that have reported an inverse association between magnesium intake or serum magnesium levels and the risk of NAFLD9,10. The observed association between higher MDS and increased MASLD risk in our study is biologically plausible. Magnesium deficiency may contribute to the development and progression of MASLD through several potential mechanisms, including inflammation, insulin resistance, and dysregulation of lipid metabolism28. Magnesium is recognized for its anti-inflammatory properties, and deficiency has been linked to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), both of which play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of MASLD29,30. Additionally, magnesium is essential for maintaining insulin sensitivity, and its deficiency may lead to insulin resistance, a key factor in the development of MASLD31. Furthermore, magnesium deficiency may impair lipid metabolism by increasing triglyceride synthesis and reducing fatty acid oxidation, thereby contributing to hepatic steatosis32.

Our mediation analyses revealed that neutrophils and WBC partially mediated the association between MDS and MASLD, highlighting the importance of inflammation in the relationship between magnesium deficiency and MASLD. Magnesium deficiency has been shown to activate the innate immune response, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can result in neutrophil infiltration and activation in the liver14,33. Once activated, neutrophils release reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, causing hepatocellular damage and exacerbating liver injury34. Additionally, magnesium deficiency may enhance the recruitment and activation of other inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, contributing to the overall inflammatory milieu in the liver33. The chronic low-grade inflammation induced by magnesium deficiency may accelerate the progression of MASLD and increase the risk of advanced liver fibrosis35.

Albumin, synthesized by the liver, is a crucial marker of hepatic synthetic function. Our mediation analysis showed that albumin had the highest mediating effect (14.05%) in the association between MDS and MASLD. This suggests that magnesium deficiency may influence risk of MASLD by affecting albumin synthesis, which reflects the extent of liver damage. Magnesium plays a key role in protein synthesis15, and its deficiency may hinder the liver’s ability to produce albumin. As MASLD progresses, liver damage and dysfunction become more pronounced, leading to a decline in albumin levels. The reduced albumin synthesis in the setting of magnesium deficiency may serve as an indicator of the severity of liver injury and contribute to the progression of MASLD. Moreover, albumin possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and its decrease could exacerbate oxidative stress and inflammation within the liver, creating a vicious cycle that promotes MASLD development36.

The subgroup and interaction analyses provide further insights into the intricate relationship between MDS and MASLD. Notably, the association between MDS and MASLD was not statistically significant among current smokers, suggesting that smoking may confound the relationship. Smoking has been identified as a risk factor for MASLD, and may contribute to disease development and progression through various mechanisms, such as insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation37,38. Moreover, smoking has been shown to deplete magnesium levels, possibly due to increased urinary excretion of magnesium39. The interaction between smoking and magnesium deficiency in the pathogenesis of MASLD requires further investigation, as these factors may have synergistic effects on the development and progression of the disease.

Age was found to be a significant effect modifier in the association between MDS and MASLD. The weakened association among participants aged ≥ 65 years suggests that age is a crucial modulating factor. This finding may be attributed to the unique physiological state and nutritional status of the elderly population. Aging is associated with a decline in magnesium absorption and an increase in urinary magnesium excretion, leading to a higher risk of magnesium deficiency40. Additionally, older adults often have multiple comorbidities and take medications that can affect magnesium homeostasis41. The complex interplay between age-related factors and magnesium status may contribute to the attenuated association between MDS and MASLD in the elderly population.

Furthermore, the nutritional status of older adults may influence the relationship between MDS and MASLD. Malnutrition is prevalent among the elderly, and may lead to deficiencies in various micronutrients, including magnesium42,43. Poor nutritional status may further contribute to the development and progression of MASLD through mechanisms, such as increased oxidative stress and inflammation44. The potential interaction between magnesium deficiency and malnutrition in the context of MASLD in the elderly population requires further exploration.

The present study has several strengths and innovations. First, we utilized data from the NHANES, a nationally representative survey of the US population with a large sample size, which enhances the generalizability of our findings45. Second, we applied the MDS, a novel and comprehensive indicator of magnesium depletion that integrates multiple clinical factors, offering a more holistic assessment of magnesium deficiency compared to single measures like serum magnesium levels46. Third, adjustments were made for a broad range of covariates, including demographic characteristics and biochemical parameters thereby improving the robustness of our results. Fourth, mediation analyses were conducted to explore the potential mediating effects of inflammation and albumin on the association between MDS and MASLD, alongside interaction analyses to investigate the modulating roles of age and smoking. These analyses provide valuable insights into mechanisms linking MDS and MASLD47.

However, our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of a causal relationship between MDS and MASLD48. Future prospective cohort studies are necessary to validate these findings and clarify the temporal sequence of the association. Additionally, the absences of liver biopsy data, which is the gold standard for assessing liver histology, is a notable limitation49. Future research should incorporate both imaging and histological evaluations for a comprehensive assessment of MASLD. Moreover, we lacked direct measures of magnesium status, such as serum magnesium concentration, which is an important indicator of magnesium nutritional status50. Including serum magnesium measurements in future studies would provide valuable insights into the relationship between MDS and MASLD. Furthermore, MASLD diagnosis in our study was based on a FLI threshold of ≥ 30, which increases diagnostic sensitivity but reduced specificity. In an effort to maximize the inclusion of high-risk individuals for MASLD in this large epidemiologic analysis, this cut-off was employed.

Future research should also aim to elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which MDS contributes to the development and progression of MASLD. Understanding these pathways could guide the creation of more targeted prevention and treatment strategies51. Furthermore, clinical trials investigating the effects and safety of magnesium supplementation in the prevention and management of MASLD are warranted52. Such studies would provide valuable evidence to guide clinical practice and public health interventions aimed at reducing the burden of MASLD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a significant association between higher MDS and increased risk of MASLD in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. These findings highlight the potential role of magnesium deficiency in the pathogenesis of MASLD and suggest that addressing magnesium depletion may be a promising strategy for the prevention and management of this increasingly prevalent condition. Further research is needed to confirm our findings, elucidate the underlying mechanisms, and explore the therapeutic potential of magnesium supplementation in the context of MASLD.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript will be made publicly and freely available without restriction at the NHANES Internet website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

References

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 64, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28431 (2016).

Estes, C. et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016–2030. J. Hepatol. 69, 896–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036 (2018).

Eslam, M. et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 73, 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039 (2020).

Sarrafzadegan, N., Khosravi-Boroujeni, H., Lotfizadeh, M., Pourmogaddas, A. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. Magnesium status and the metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 32, 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.09.014 (2016).

Zheltova, A. A., Kharitonova, M. V., Iezhitsa, I. N. & Spasov, A. A. Magnesium deficiency and oxidative stress: An update. Biomed. (Taipei). 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.7603/s40681-016-0020-6 (2016).

Arancibia-Hernández, Y. L., Hernández-Cruz, E. Y., Pedraza-Chaverri, J. & Magnesium Mg(2+)) Deficiency, Not Well-recognized non-infectious pandemic: Origin and consequence of chronic inflammatory and oxidative stress-Associated diseases. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 57, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.33594/000000603 (2023).

Hosseini Dastgerdi, A., Ghanbari Rad, M. & Soltani, N. The therapeutic effects of Magnesium in insulin secretion and insulin resistance. Adv. Biomed. Res. 11, 54. https://doi.org/10.4103/abr.abr_366_21 (2022).

Dai, W., Wang, K., Zhen, X., Huang, Z. & Liu, L. Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate attenuates acute alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis in a zebrafish model by regulating lipid metabolism and ER stress. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 19, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-022-00655-7 (2022).

Eshraghian, A., Nikeghbalian, S., Geramizadeh, B. & Malek-Hosseini, S. A. Serum magnesium concentration is independently associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 6, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640617707863 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Intakes of magnesium, calcium and risk of fatty liver disease and prediabetes. Public. Health Nutr. 21, 2088–2095. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980018000642 (2018).

Van Laecke, S. Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia. Acta Clin. Belg. 74, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2018.1516173 (2019).

Tangvoraphonkchai, K. & Davenport, A. Magnesium and Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 25, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2018.02.010 (2018).

Orchard, T. S. et al. Magnesium intake, bone mineral density, and fractures: Results from the women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99, 926–933. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.067488 (2014).

Bussière, F. I., Tridon, A., Zimowska, W., Mazur, A. & Rayssiguier, Y. Increase in complement component C3 is an early response to experimental magnesium deficiency in rats. Life Sci. 73, 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00291-1 (2003).

Rubin, A. H., Terasaki, M. & Sanui, H. Major intracellular cations and growth control: Correspondence among magnesium content, protein synthesis, and the onset of DNA synthesis in BALB/c3T3 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 76, 3917–3921. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.76.8.3917 (1979).

Alkhouri, N. et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio: A new marker for predicting steatohepatitis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 32, 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02639.x (2012).

Shobi, V., Adeseye, A., Billy, B. & Medhat, K. Hemochromatosis, alcoholism and unhealthy dietary fat: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-02610-7 (2021).

Takahashi, H. et al. Association of Serum Albumin Levels and long-term prognosis in patients with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092014 (2023).

Li, J., Delamarre, A., Wong, V. W. & de Lédinghen, V. Diagnosis and assessment of disease severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 12, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/ueg2.12491 (2024).

EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical practice guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 81, 492–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.04.031 (2024).

Ruhl, C. E. & Everhart, J. E. Fatty liver indices in the multiethnic United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 41, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13012 (2015).

Ma, N. et al. Environmental exposures are important risk factors for advanced liver fibrosis in African American adults. JHEP Rep. 5, 100696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100696 (2023).

Tan, Z. et al. Trends in oxidative balance score and prevalence of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2018. Nutrients. 15https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234931 (2023).

Han, A. L. Validation of fatty liver index as a marker for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00811-2 (2022).

Abdelhameed, F. et al. Non-invasive scores and serum biomarkers for fatty liver in the era of metabolic dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A comprehensive review from NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD. Curr. Obes. Rep. 13, 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-024-00574-z (2024).

US Department of Health and Human Services; US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services. December (2015). http://www.health.gov/

Drinking Patterns and Their Definitions. Alcohol Res. 39, 17–18 (2018).

Yuan, S. et al. Lifestyle and metabolic factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Mendelian randomization study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 37, 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-022-00868-3 (2022).

Mazur, A. et al. Magnesium and the inflammatory response: Potential physiopathological implications. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 458, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.031 (2007).

Almoznino-Sarafian, D. et al. Magnesium and C-reactive protein in heart failure: An anti-inflammatory effect of magnesium administration? Eur. J. Nutr. 46, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-007-0655-x (2007).

Guerrero-Romero, F. & Rodríguez-Morán, M. Hypomagnesemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 22, 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.644 (2006).

Rayssiguier, Y., Gueux, E. & Weiser, D. Effect of magnesium deficiency on lipid metabolism in rats fed a high carbohydrate diet. J. Nutr. 111, 1876–1883. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/111.11.1876 (1981).

Yang, J. et al. Discovery of isoliquiritigenin analogues that reverse acute hepatitis by inhibiting macrophage polarization. Bioorg. Chem. 114, 105043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105043 (2021).

Ibarra-Lara Mde, L. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) downregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in an experimental model of myocardial infarction. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2015-0356 (2016).

Matsui, T. [Magnesium and liver]. Clin. Calcium. 22, 1181–1187 (2012).

Arroyo, V., García-Martinez, R. & Salvatella, X. Human serum albumin, systemic inflammation, and cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 61, 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.012 (2014).

Sinha, N. & Dabla, P. K. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in hypertension-a current review. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 11, 132–142. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573402111666150529130922 (2015).

Kim, C. H., Park, J. Y., Lee, K. U., Kim, J. H. & Kim, H. K. Fatty liver is an independent risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes in Korean adults. Diabet. Med. 25, 476–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02410.x (2008).

Wang, M. et al. Magnesium intake and all-cause mortality after stroke: A cohort study. Nutr. J. 22, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-023-00886-1 (2023).

Barbagallo, M., Belvedere, M. & Dominguez, L. J. Magnesium homeostasis and aging. Magnes Res. 22, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1684/mrh.2009.0187 (2009).

Khow, K. S., Lau, S. Y., Li, J. Y. & Yong, T. Y. Diuretic-associated electrolyte disorders in the elderly: Risk factors, impact, management and prevention. Curr. Drug Saf. 9, 2–15. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574886308666140109112730 (2014).

Volkert, D. et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 38, 10–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024 (2019).

Barbagallo, M., Veronese, N. & Dominguez, L. J. Magnesium in aging, Health and diseases. Nutrients. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020463 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Updated mechanisms of MASLD pathogenesis. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02108-x (2024).

Zipf, G. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. 1, 1–37 (2013).

Costello, R. B. et al. Perspective: The case for an evidence-based reference interval for serum magnesium: The time has come. Adv. Nutr. 7, 977–993. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.012765 (2016).

VanderWeele, T. J. Mediation analysis: A practitioner’s guide. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 37, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021402 (2016).

Sedgwick, P. Cross sectional studies: Advantages and disadvantages. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2276 (2014).

Brunt, E. M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pros and cons of histologic systems of evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010097 (2016).

Workinger, J. L., Doyle, R. P. & Bortz, J. Challenges in the diagnosis of magnesium status. Nutrients. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091202 (2018).

Noureddin, M. & Sanyal, A. J. Pathogenesis of NASH: The impact of multiple pathways. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 17, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-018-0425-7 (2018).

Schwalfenberg, G. K. & Genuis, S. J. The importance of magnesium in clinical healthcare. Scientifica (Cairo). 2017 (4179326). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4179326 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the NHANES research team for collecting, managing, and providing access to the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This NHANES study was approved by the NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) Ethics Review Board. Informed consent forms were signed by participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, F., Li, Y., Wang, Y. et al. Association between magnesium depletion score and the risk of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease: a cross sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 24627 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75274-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75274-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypomagnesemia: exploring its multifaceted health impacts and associations with blood pressure regulation and metabolic syndrome

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)

-

Association between magnesium depletion score and prostate cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)