Abstract

Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC) plays a crucial role in sustainable land management and regional planning. However, contemporary feature extraction approaches often prove inefficient at capturing critical data features, thereby complicating land cover categorization. In this research, we introduce a new feature extraction algorithm alongside a Segmented and Stratified Principal Component Analysis (SS-PCA) dimensionality reduction method based on correlation grouping. These methods are applied to UAV LiDAR and UAV HSI data collected from land use types (e.g., residential areas, agricultural lands) and specific species (e.g., tree species) in urban, agricultural, and natural environments to reflect the diversity of the study area and to demonstrate the ability of our methods to be applied in different classification scenarios. We utilize LiDAR and HSI data to extract 157 features, including intensity, height, Normalized Digital Surface Model (nDSM), spectral, texture, and index features, to identify the optimal feature subset. Subsequently, the best feature subset is inputted into a random forest classifier to classify the features. Our findings demonstrate that the SS-PCA method successfully enhances downscaled feature bands, reduces hyperspectral data noise, and improves classification accuracy (Overall Accuracy = 91.17%). Additionally, the CFW method effectively screens appropriate features, thereby increasing classification accuracy for LiDAR (Overall Accuracy = 78.10%), HIS (Overall Accuracy = 89.87%), and LiDAR + HIS (Overall Accuracy = 97.17%) data across various areas. Moreover, the integration of LiDAR and HSI data holds promise for significantly improving ground fine classification accuracy while mitigating issues such as the ‘salt and pepper noise’. Furthermore, among individual features, the LiDAR intensity feature emerges as critical for enhancing classification accuracy, while among single-class features, the HSI feature proves most influential in improving classification accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC) is a primary catalyst for various land-based chain reactions. LUCC impacts energy interconversion within the Earth, which subsequently influences regional climate conditions, the water cycle, ecosystem stability, and socio-economic factors1,2. Accurate land use information is crucial for sustainable land management3, ecological conservation4, urban and regional planning5, and natural disaster monitoring6, all of which are vital to human livelihoods. While mapping land use is recognized as essential for responsible land use, our understanding of land use coverage and dynamics remains limited7. The necessity for precise and detailed land use mapping is particularly pronounced in developing nations experiencing rapid population and economic growth, aiming to maximize the benefits of demographic dividends8. Airborne LiDAR and hyperspectral technologies have undergone significant advancements, and their combined utilization holds promise in effectively addressing these challenges.

With the rapid advancement of remote sensing technology and the emergence of hyperspectral sensors, the field of image analysis has seen significant progress. Hyperspectral images (HSI) offer a greater number of narrow-band imaging bands compared to conventional multispectral images, providing exceptional object identification and classification capabilities along with rich spectral information on land types9. Consequently, researchers increasingly utilize HSI for land use classification10. However, the high dimensionality of HSI poses challenges, prompting the extraction of information related to principal components, texture features, and narrow-band vegetation indices using remote sensing techniques to facilitate fine-scale land use classification11,12,13. For instance, Rodarmel and Shan14 employed principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of hyperspectral data and utilized a maximum likelihood classifier, achieving a maximum overall correct rate of 70%. Nevertheless, due to the subtle spectral differences between different land classes, classification results may be suboptimal. Classification based on vegetation indices can effectively amplify spectral differences and enhance subtle changes in spectral profiles to improve final classification accuracy15.

Historically, the structural information of various features has relied on field surveys, which are inefficient and costly. However, with the introduction of LiDAR technology, it has become possible to efficiently obtain structural information on diverse ground types and to classify them swiftly and effectively16. LiDAR not only provides vertical information about the ground but also intensity information. Traditionally, the primary objective of LiDAR classification has been to differentiate ground points from above-ground points17. Over time, numerous scholars have utilized LiDAR-derived information for height and intensity feature extraction to classify the extracted features. For instance, Michałowska and Rapiński18 extracted geometric, intensity, and waveform features from LiDAR data and successfully classified ground tree species using random forest and support vector machine classifiers. However, LiDAR alone cannot effectively capture semantic and textural information about ground features. Moreover, LiDAR point clouds exhibit discrete, irregular, and discontinuous characteristics, posing challenges for ground feature classification using single LiDAR point cloud data, which has yet to achieve significant success.

The absence of information in hyperspectral images regarding the size and elevation of various land types can result in misclassification and the oversight of phenomena such as 'the same spectrum but foreign object’ and 'the same objects but different spectrum’. While hyperspectral images have been successfully used to recognize land use/land cover (LULC) and other classes, integrating LiDAR data with hyperspectral data can provide additional spatial and structural characteristics that enhance classification accuracy, especially in complex landscapes. For instance, Hänsch and Hellwich19 employed a Random Forest (RF) classifier to classify urban land cover, achieving an overall accuracy of 65.90% by integrating Digital Surface Models (DSM), LiDAR intensity characteristics, and hyperspectral data. Similarly, Buján et al.20 combined orthophotos with LiDAR point cloud data for land use classification in rural areas, and the accuracy reaches 96.4%. Sankey et al.21 merged hyperspectral data with LiDAR point cloud data to distinguish land cover and tree species in the western United States, and the accuracy reaches 88%. However, the combination of these two datasets without feature optimization often results in redundant data and unreliable classification outcomes. Therefore, it is essential to optimize features extracted from both LiDAR and hyperspectral datasets to enhance classification accuracy and efficiency.

Extracting useful features from Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and LiDAR point cloud data is crucial for effectively increasing classification accuracy. However, this can result in a large number of segmented features22, potentially containing redundant data. Therefore, inputting all these features into the classifier for ground classification may not be the most optimal approach, underscoring the importance of effective feature subset extraction. To address these challenges, feature extraction methods are categorized into three primary types of algorithms: Filtering, Wrapper, and Embedding23. Among these, filtering algorithms and wrapper algorithms are most commonly utilized. Filtering algorithms select feature subsets based on the general performance of the features, without considering subsequent learners. For instance, Huang and He24 employed the Relief-F algorithm to effectively reduce the dimensionality of hyperspectral features and achieve good classification results. Building upon this, Ren et al.25 introduced the partitioned Relief-F technique, which also successfully reduces the dimensionality of hyperspectral features. However, the Relief-F algorithm may underestimate less prominent features as it does not consider data modeling techniques. In contrast, wrapper algorithms consider feature subsets based on the performance quality of the modeling algorithm. While wrapper algorithms rely heavily on the modeling algorithm to filter out the optimal feature subset, they are slower in efficiency compared to filtering algorithms. For example, Demarchi et al.26 combined recursive feature elimination (RFE) with random forest to extract 24 optimal features for hyperspectral data and LiDAR point cloud data with a kappa coefficient of 0.77. Almeida et al.27 utilized RFE to filter the two most important features of HSI and LiDAR data, achieving good classification results. Viinikka et al.28 extracted important features of HSI and LiDAR data using the support vector machine (SVM)-based RFE algorithm and effectively-identified European Poplar with an overall correct rate of 84%. Thus, selecting a minimum and the most effective subset of features from numerous features poses a significant challenge, highlighting the importance of employing appropriate feature extraction algorithms.

This study aims to investigate a fully automatic selection algorithm for multiple features of hyperspectral data and LiDAR point cloud data, along with a dimensionality reduction method for hyperspectral data. It also seeks to validate the applicability of a fine ground classification method based on the fusion of hyperspectral images obtained by UAV and LiDAR point cloud data. In this study, we address the issue of selecting too many principal component bands, which can lead to noise and diminish classification performance, by enhancing the dimensionality reduction approach of PCA based on inter-band correlation. Additionally, to tackle the problem of the high number of features in land use classification, we aim to extract high-quality feature subsets quickly to avoid the “Hughes” phenomenon. Considering that the filtered Relief-F algorithm may have information overlap and can only serve as an initial screening, and the RFE algorithm may not adequately consider model features, we propose a new feature extraction method called CFW. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of integrating UAV hyperspectral and LiDAR data for detailed land use/land cover (LULC) classification. We chose to classify land use types (e.g., residential areas, agricultural lands) and specific species (e.g., tree species) in urban, agricultural, and natural environments to reflect the diversity of the study area and to demonstrate the ability of our method to be applied in different classification scenarios. This method aims to effectively address the aforementioned problems. Although the fusion of hyperspectral data with LiDAR point cloud data for classification has been recognized, the unique objectives of this study are:

-

1.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the SS-PCA method in the dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral data, specifically focusing on its ability to preserve essential spectral information while reducing data complexity.

-

2.

To assess the performance of the CFW algorithm in selecting optimal feature subsets, thereby enhancing classification accuracy by leveraging the most relevant data features.

-

3.

To analyze the impact of specific LiDAR and hyperspectral characteristics, such as elevation data from LiDAR and spectral indices from HSI, on overall classification accuracy. This analysis will provide insights into the contributions of each data type in a multi-source remote sensing context.

Study area and data

Study area

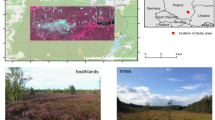

This study was conducted in Shizuishan City (106°23′E, 38°59′N), located in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of northern China (Fig. 1). Shizuishan City experiences a typical temperate continental climate with abundant heat, sunlight, minimal drought, and significant diurnal temperature variation, with an average annual temperature of 9.2 °C and average annual precipitation of 177 mm. The study area encompasses approximately 11.5 hectares, with elevations ranging from 1056 to 1062 m. The overall topography is characterized as flat and minimally undulating. Situated in a rural area, the study area is predominantly divided into residential zones and areas for crop cultivation. Considering the characteristics of the study area, eight distinct categories of features will be finely classified, including corn fields, buildings, areas of accumulated plastic boxes, aspen trees, roads, bare ground, low vegetation, and floating duckweed.

The location of the study area. This figure was generated using ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/arcgis-for-desktop).

The location of Verification Area I corresponds to Study Area I, covering approximately 2.1 hectares and primarily comprised of buildings, is depicted in Fig. 1b. Seven distinct categories of features, namely Building, Duckweed, Bare land, Plastic box, Road, and Scrubby vegetation, will be accurately categorized within the study area based on its feature characteristics.

Verification Area II is located in Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, East China (30°22′ to 31°11′N and 119°14′ to 120°29′E) (Fig. 1c). The verification area covers approximately 1.3 hectares and is predominantly characterized by tree concentration. Considering the feature characteristics of the study area, eleven types of features will be finely categorized, including Atropurpureum, Bamboo, Building, Eggplant, Ginkgo, Bare land, River, Road, Scrubby vegetation, Tea, and Torreya. In this study, Verification Area I and Verification Area II were utilized as validation areas for assessing the effectiveness of the proposed methodology.

The study area encompasses urban, agricultural, and natural environments and is highly diverse. To accurately reflect this diversity, we chose categories that encompassed both land use types (e.g., residential areas, agricultural lands) and specific species (e.g., different tree species). This choice ensures that our categories capture the full range of relevant features within the study area.

Remote sensing data and preprocessing

LiDAR data

On August 3, 2022, UAV-based LiDAR data for the study area were acquired using the GreenValley International LiAir220N (Table 1) system mounted on a DJI Matrice 300 RTK quadcopter (DJI, Shenzhen, China). The UAV was flown in a loop over the study area at an altitude of approximately 100 m and a speed of 7 m per second. The flight path ensured an 80% heading overlap and a 70% side overlap. Multiple echoes were recorded during the flight, resulting in an average point cloud density of more than 1700 points/m2. However, point clouds acquired using these sensors are inevitably contaminated with noise and contain outliers due to factors such as weather and inherent sensor noise. Therefore, in this study, the acquired point clouds were denoised based on LiDAR360 software and the Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN) algorithm was used to acquire the DEM of the study area.

Hyperspectral data

On August 3, 2022, hyperspectral data for the study area were acquired using a Cubert S185 (Table 2) hyperspectral sensor mounted on a DJI Matrice 300 RTK quadcopter (DJI, Shenzhen, China). To minimize the influence of sunlight on the hyperspectral data, data acquisition was conducted between 11:10 and 13:00, during which the sun’s elevation angle was the highest and the sunlight shadow was stable. Since the UAV hyperspectral image is being spliced with outward expansion at the edges, we need to crop the image data; and since the UAV acquired 138 bands, but the number of effective bands is 125, and bands exceeding 125 are considered noisy, we need to remove the noisy bands. Pre-processing of UAV hyperspectral data, including image cropping and atmospheric correction, is all performed in ENVI 5.3.

To mitigate the impact of dark currents and fiber optics on image quality, reflectance calibration of the sensor was performed before hyperspectral data acquisition. This involved sequentially capturing calibration images of a white calibration plate made of Poly Tetra Fluoroethylene (PTFE) material with 100% reflectance and a masked sensor in a light-free environment with 0% reflectance. Reflectance was calculated using these calibration images. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where \(I_{O}\) is the original hyperspectral image, \(I_{W}\) is the white calibration plate image with 100% reflectance, and \(I_{D}\) is the calibration image with 0 reflectance.

Method

Features construction

LiDAR features

LiDAR point cloud data is mostly composed of the following data: X, Y, Z, intensity data, echo count, GPS, and scan angle of the points. For extracting LiDAR features, two types of information are mostly used: the first is the height information of the points, and the second is the intensity information of the points returned. In this study, a total of 98 LiDAR features are calculated, including 42 intensity features and 56 height features.

Intensity features

Intensity is a measurement indicator that reflects the intensity of the LIDAR pulse echoes generated at a point. The intensity information has a great relationship with the material of the measured target and the roughness of the surface. Different measured targets will generate different echo intensities, and the intensity information can effectively separate the features. A total of 42 intensity features are calculated, and the specific intensity features are shown in Table 3.

Height features

Height variables are statistical parameters related to point cloud elevation values, and a total of 46 statistical variables related to height and 10 statistical variables related to point cloud density can be calculated, and the specific height characteristics are shown in Table 4.

nDSM

The original point cloud is filtered using LiDAR 360 software with the Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN) filtering method to eliminate noisy points and categorize the point cloud into ground and non-ground points. Ground and non-ground points are interpolated using the irregular triangular mesh method to create the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and Digital Surface Model (DSM) with a grid resolution of 0.01 m. The interpolated DEM and DSM undergo different operations to produce the Normalized Digital Surface Model (nDSM) as shown in Fig. 2.

Spectral features

Spectral reflectivity

Hyperspectral imaging provides higher spectral resolution and captures a more continuous spectral band compared to multispectral imaging, which mainly records electromagnetic wave reflection information within specific areas (Fig. 3). Increased spectral detail in hyperspectral data can more accurately highlight distinctions between different features due to their practical differences. On August 3, 2022, under clear and cloudless weather conditions, hyperspectral data consisting of 138 bands was collected during a flight at a height of 100 m and a speed of 7 m/s. An 80% heading overlap rate and a 70% side overlap rate were maintained. Influenced by the sensors, the bands beyond 125 bands are often subject to sudden fluctuations due to airborne gases, moisture, and particulate matter that can interfere with the spectral information, which can easily lead to problems with the quality of the acquired data, so we retain the first 125 bands.

Texture features

Texture is a visual attribute that characterizes homogeneous patterns within an image, encapsulating intrinsic properties shared by the surface of an object. It provides valuable information about the structural organization of the surface and its relationship with the surrounding environment. In ground information extraction, the occurrence of 'the same spectrum but foreign object’ increases with higher image resolutions. While high-resolution UAV imagery enhances the depiction of feature details and highlights differences between them, it also introduces spectral information loss. Consequently, relying solely on spectral data for ground class extraction may result in misclassification and feature omission. Texture features complement spectral information by describing surface characteristics and spatial relationships within remote sensing images, so we chose it to capture structural and vegetation differences between land cover types. They offer insights into the grayscale properties and spatial arrangement of features, aiding in the description of global scene attributes. Among various feature extraction methods, probabilistic statistical filtering stands out as a widely utilized approach for effectively extracting texture features. In this study, the first principal component of the original 125 bands of hyperspectral data was analyzed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Texture features were then computed from 3 × 3 to 15 × 15 windows using the HaralickTextureExtraction tool within the Orfeo ToolBox (OTB), a free and open-source remote sensing program. In the process of feature selection, During the feature selection process, it was found to be most efficient to use a step size of 1 and a kernel size of 5 × 5 size for feature computation. Results indicated that texture features extracted from 7 × 7 windows yielded optimal performance. Table 5 presents the estimation of eight higher-order parameters, nine advanced parameters, and seven simple parameters using the OTB program, providing comprehensive insights into the texture characteristics of the study area.

Spectral index features

Vegetation indices (VIs) play a crucial role in remote sensing analysis as they offer a robust representation of vegetation characteristics by combining spectral information from multiple bands. These indices are formed by linear and nonlinear combinations of spectral bands, and our choice of vegetation indices as spectral features is intended to capitalize on their ability to clearly highlight specific vegetation features. The specific vegetation indices (VIs) chosen for this study, such as NDVI, SAVI, and others, were selected based on their proven effectiveness in previous studies and their relevance to the specific vegetation types present in our study area. For example, NDVI was chosen due to its sensitivity to chlorophyll content, which is crucial for distinguishing between different vegetation categories. SAVI was included to mitigate the impact of soil brightness, making it particularly useful in areas with sparse vegetation. The combination of these indices provides complementary information. By integrating indices that emphasize different aspects of vegetation, such as canopy structure, chlorophyll content, and soil influence, our approach ensures more robust and accurate classification results. Numerous vegetation indices have been developed by researchers to cater to various application needs, leveraging the spectral characteristics of vegetation across different wavelengths. In this study, vegetation indices were generated using ENVI software, utilizing hyperspectral band wavelengths. A total of 27 vegetation indices were selected as spectral index features for the hyperspectral data analysis. Table 6 provides details of the specific vegetation indices calculated for this study.

Feature extraction

Hyperspectral data dimensionality reduction method based on segmented PCA

Hyperspectral sensors offer the advantage of capturing detailed spectral information about features; however, their high dimensionality can lead to the “Hughes” phenomenon. This phenomenon refers to the presence of numerous redundant bands in hyperspectral data, resulting in prolonged computation times and ineffective classification. To address this issue, low-information spectral bands are typically eliminated during data processing to reduce interference and improve classification efficiency while retaining maximum spectral information52. Various methods exist for the dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral image data, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Minimum Noise Fraction (MNF), Independent Component Analysis (ICA), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), among others. Among these, PCA is the most widely used method, and this paper adopts PCA for band dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral image data.

PCA works by transforming the original data characteristics and replacing the original variable indicators with a smaller set of integrated feature values. These new indicators are independent of each other and accurately represent the information conveyed by the original variables. However, classic PCA may not adequately capture the significant information of local bands, leading to the loss of important information and compromising classification accuracy. To address this limitation, Jia and Richards53 proposed the Segmented Principal Component Transform (S-PCT) method, which clusters hyperspectral data based on correlations exceeding a threshold value to select the most dominant components. While effective for overall classification, this approach may not perform well for fine classification due to strong inter-band correlations. To fully extract key information from hyperspectral images, this study introduces an improved version of S-PCT called SS-PCA (Segmented and Stratified PCA). SS-PCA enhances PCA by considering high correlations between bands. The hyperspectral data are first categorized according to the correlation coefficient, which is determined by the following particular formula:

where \(R_{ij}\) is the correlation between the i band and j band of the hyperspectral image, m and n represent the rows and columns of image elements, respectively, the numerator is calculated as the covariance of the two band vectors, and the denominator is the product of the two band vector variances.

Bands with correlation values exceeding 0.95 are grouped together to effectively extract key feature data from local bands. Subsequently, PCA analysis is conducted using OTB software on these grouped bands. The first two principal component bands of each group are selected because, according to conventional PCA dimensionality reduction methods, the majority of information is concentrated in these bands. Choosing more principal component bands may introduce significant noise, thereby reducing classification accuracy. In this study, the collected hyperspectral data were divided into four groups based on correlation coefficients among the 125 bands: bands 1 to 20, bands 21 to 53, bands 54 to 72, and bands 73 to 125. PCA analysis was performed on each group, and the first eight principal component bands from the analysis of the original 125 hyperspectral bands were retained for subsequent comparison studies.

ReliefF-Person algorithm

The Relief algorithm, introduced by Kira and Rendell54, was proposed as a method to reduce the dimensionality of feature data for binary classification problems. It assigns weights to features based on their relevance to the target type. In 1994, Kononenko extended this algorithm and introduced the ReliefF algorithm, a multivariate filtering feature extraction method. ReliefF addresses feature extraction and missing data handling in multi-category classification by evaluating the weights of each feature based on the principle of finding various types of nearest-neighbor samples for the current sample. While the features extracted using the ReliefF algorithm can adequately represent features with more information, there may be information overlap between features, resulting in increased data redundancy and slower data processing. To address this, this paper combines the Pearson correlation coefficient method to further screen the extracted features. A low correlation between features indicates low data redundancy between them. Consequently, features are further screened using the principle of feature preference: high weight and low association with others. This combined approach aims to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of feature extraction for classification tasks.

Assume that the training data set is \(S\), the number of nearest neighbor samples is \(k\), the number of iterations is \(n\) , the number of sampling times is \(m\), and the specific steps to determine the weights of each feature in the training data set \(S\) using the Relief F-Person algorithm are:

-

1.

Randomly select a sample from the training data set \(S\) and denote it as \(R\).

-

2.

Select \(k\) nearest neighbor samples (closest distance to \(R\)) from samples of the same class (same category label) as \(R\) and calculate the distance \(\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff\left( {f_{i} ,R,H_{j} } \right)\), and select \(k\) nearest neighbor samples from samples of different class (different category label) as \(R\) and calculate the distance \(\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff(f_{i} ,R,M_{j} \left( c \right))\).

-

3.

The weights corresponding to the feature are continuously updated according to Eq. (3) and calculated \(n\) times until all samples are calculated in turn to obtain the final weight \(W^{i} \left( {f_{i} } \right)\) of a single feature.

-

4.

The weight single iteration equation is

$$\begin{aligned} W^{i + 1} \left( {f_{i} } \right) & = W^{i} \left( {f_{i} } \right) - \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff\left( {f_{i} ,R,H_{j} } \right)/\left( {m*k} \right) \\ & \;\;\; + \mathop \sum \limits_{c \ne class\left( R \right)} \left[ {\frac{P\left( c \right)}{{1 - P\left( {class\left( R \right)} \right)}}*\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff(f_{i} ,R,M_{j} \left( c \right))} \right]/\left( {m*k} \right) \\ \end{aligned}$$(3)where \(class\left( R \right)\) denotes the class in which the sample \(R\) is located; \(P\left( c \right)\) denotes the probability of the target of class \(c\), which is generally divided by the number of samples of the target of that class by the total number of samples; \(P\left( {class\left( R \right)} \right)\) denotes the probability of the class in which \(R\) is located.

\(diff\left( {a,R_{1} ,R_{2} } \right)\) denotes the difference between the samples on \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\) on the feature \(f_{i}\), which is calculated as follows.

$$diff\left( {a,R_{1} ,R_{2} } \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {\frac{{\left| {R_{1} \left[ {f_{i} } \right]} \right| - \left| {R_{2} \left[ {f_{i} } \right]} \right|}}{{\max \left( {f_{i} } \right) - {\text{min}}\left( {f_{i} } \right)}}} \hfill & {if f_{i} is continuous} \hfill \\ 0 \hfill & {if f_{i} is discrete and R_{1} [f_{i} ] = R_{2} \left[ {f_{i} } \right]} \hfill \\ 1 \hfill & { if f_{i} is discrete and R_{1} [f_{i} ] \ne R_{2} \left[ {f_{i} } \right]} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(4)where \(R_{1} [f_{i} ]\) and \(R_{2} [f_{i} ]\) denote the sample values under samples \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\), respectively.

-

5.

The weights of all features are ranked and the Pearson correlation coefficient between any two features is computed sequentially and features with correlation coefficients < 0.5 are retained. The Pearson correlation coefficient formula is as follows:

$$r_{xy} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = 1}^{n} \left[ {\left( {x_{t} - \overline{x}} \right)\left( {y_{t} - \overline{y}} \right)} \right]}}{{\sqrt {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = 1}^{n} (x_{t} - \overline{x})^{2} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = 1}^{n} (y_{t} - \overline{y})^{2} } }}$$(5)where \(r_{xy}\) is the correlation coefficient between any two features x,y, \(\overline{x}\) is the average of all x, and \(\overline{y}\) is the average of all y.

Random Forest-Recursive Feature Elimination—Cross Validation algorithm

The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method was initially proposed by Guyon et al.55. This algorithm, classified as a greedy optimization algorithm and a representative of the Wrapper algorithm, operates by continuously adding or removing features to train the model and obtain the optimal subset of features. Initially, the algorithm selects all features for training the model, ranks their importance, retains the top features, retrains the model, and iterates this process until reaching the specified number of features or iterations, resulting in the ideal feature subset. In this study, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm-based feature extraction method is employed, utilizing the RF-RFE-CV approach. This choice is made to mitigate the impact of redundant information on the algorithm and enhance prediction accuracy. The specific steps involved are as follows:

-

1.

Inputting data sets and normalizing the data.

-

2.

Construct RF models to calculate feature importance and obtain feature rankings based on their importance scores.

-

3.

Remove the features with the minimum weight from the feature set according to STEP 2.

-

4.

Repeat STEP 3, iteratively, to find the optimal feature subset, using the cross-validation results.

-

5.

Record the cross-validation scores and retrain the remaining features to obtain the new feature ranking.

Combination Feature Weighting (CFW) algorithm

The filtering algorithm, while relatively simple, offers efficient computational efficiency and satisfactory results. However, one of its limitations is its inability to effectively eliminate redundant variables, which can lead to a decrease in classifier performance due to biased discriminative findings caused by redundant and noisy variables. To address this limitation, a correlation analysis is conducted on the selected candidate feature subset, followed by further filtering based on feature preference for low correlation. However, this preliminary evaluation may not fully utilize the potential of the selected features. To achieve the optimal feature subset, it is crucial to employ an effective feature search algorithm. In contrast to the filtering algorithm, the wrapper algorithm is more focused and evaluates a subset of features based on the learner’s performance. The wrapper algorithm aims to use the classifier’s recognition rate to assess feature performance and construct the final classification model using the chosen features. While the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method selects features solely based on their weights without considering the model’s performance, cross-validation can effectively address this issue by obtaining the ranking of each feature based on the model, performing model training and cross-validation on the selected feature subset, and ultimately selecting the subset with high ratings. To Integrate the advantages of both the filtering and wrapper algorithms, the proposed method combines the Relief algorithm with the Pearson correlation coefficient for initial feature pre-selection. This approach effectively eliminates irrelevant features by considering both feature weights and correlations, retaining only those that contribute to classification while reducing data redundancy. Furthermore, the wrapper algorithm based on Random Forest, termed RFE-CV, continuously reduces the search space using feature data, accurately assesses feature variables, filters out crucial features for classification, and builds the CFW algorithm. The key steps involved are as follows:

-

1.

A sample is randomly selected from the training data set S and noted as \(R\).

-

2.

Select \(k\) nearest neighbor samples (closest distance to \(R\)) from samples with the same class \(R\)(same category label) and calculate the distance \(\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff\left( {f_{i} ,R,H_{j} } \right)\), and select \(k\) nearest neighbor samples from samples with different class \(R\) (different category label) and calculate the distance \(\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{k} diff(f_{i} ,R,M_{j} \left( c \right))\).

-

3.

The weights corresponding to the feature are continuously updated according to the single iteration of the weights formula (Eq. 3), which is calculated n times until all samples are calculated in turn to obtain the final weight \(W^{i} \left( {f_{i} } \right)\) of a single feature.

-

4.

Sort by the weights \(W^{i} \left( {f_{i} } \right)\) and filter out the top 50% feature subset \(x_{i}\).

-

5.

Calculate the correlation coefficients between feature subsets \(x_{i}\) and filter out the feature subsets \(x_{k}\) with correlation coefficients less than 0.5.

-

6.

Use the feature subset \(x_{k}\) as the input of RFE algorithm and normalize it to improve the model convergence speed and accuracy, and briefly avoid the influence of outliers and extreme values by centralization.

-

7.

construct the RF model, set n_estimators = 40, max_depth = 12, max_features = 1, min_samples_leaf = 1, min_samples_split = 14,criterion = ‘gini’, random_state = 150. Output feature importance according to feature_importances.

-

8.

To rank the feature importance, set REF elimination step = 1, cross-validation rule cv = 10, average score index is prediction accuracy scoring = ‘accuracy’, if scoring ≥ max,then max = scoring, then take the current set as the optimal feature subset.

-

9.

Repeat step 8,iterate one by one, knowing that the set of feature subsets with the highest scoring value is found and identified as the optimal feature subset \(x_{j}\).

Classification method

Random forest

Breiman56 introduced the random forest technique as an ensemble learning classifier in 2001. This approach significantly enhances the model’s capacity for fitting and generalization. Another notable advantage is the algorithm’s efficiency in training, particularly with large datasets. Random forests can generate numerous trees simultaneously without the need for normative datasets, and each tree operates independently of the others. Additionally, internal tests conducted during the training process help assess the significance of predictor variables. Random forests have demonstrated high accuracy in various applications, including LiDAR and hyperspectral data fusion for categorization tasks. Therefore, this study utilizes the random forest approach for both classification and regression modeling.

Training set and test set partition

During the integration of field surveys with high-resolution UAV imagery, a stratified sampling approach was employed to ensure accurate classification, with 70% of the data allocated for training and 30% for testing. In the Study Area and Verification Area 1, both located within the same region where land cover types are relatively concentrated, preliminary surveys were conducted during UAV data acquisition to identify the locations of various land cover types. The high resolution of the UAV imagery allowed for the visual interpretation of the characteristics of the randomly selected points. For the Study Area, 15,000 points were randomly generated using ArcGIS 10.5, with 10,500 points used for training and 4500 for testing. Similarly, in Verification Area 1, 5000 points were generated, with 3500 used for training and 1500 for testing. In Verification Area 2, which contains 11 distinct land cover types, we initially used RTK to collect 100 GPS points for different vegetation types due to the difficulty of identifying certain tree species in UAV images. An additional 900 points were then randomly generated using ArcGIS 10.5, and these were verified through visual interpretation combined with the GPS data, resulting in a total of 1000 sample points. Verification Area 3 utilized a public dataset comprising 15 different land cover types, with a total of 15,029 samples, including 2832 training samples and 12,197 testing samples. The specific sample set is shown in Table 7 and the specific distribution is shown in Fig. 4.

Accuracy evaluation

Since the classification result map can only visualize the classification, the classification accuracy of remote sensing images aims to better evaluate the classification results of different experimental methods and combinations of experiments, this paper uses Overall Accuracy (OA), Recall, and F1 Score degrees for evaluation57. Where Ture Positive (TP) is the correctly predicted positive classification result, False Positive (TP) is the incorrectly predicted positive classification result, Ture Negative (TN) is the correctly predicted negative classification result and False Negative (FN) is the incorrectly predicted negative classification result. Due to the high resolution of the UAV imagery and the fact that the image crops were found to be well recognized through the field survey, ArcGIS 10.5 was used to generate 1500 random points within the study area. The feature types of the 1500 random points were determined using visual interpretation and fieldwork, of which 1050 points were used as a training set and 450 points were used as a validation set. Confusion matrix calculation was also executed and classification accuracy was discriminated.

where \(a_{c}\) is the number of true samples in class c, \(b_{c}\) is the number of samples predicted in class c, and n is the total number of samples.

Classification scheme

To compare the classification accuracy with different data and different algorithms, three different feature subsets, LiDAR, Hyperspectral, and LiDAR + Hyperspectral, were divided into no algorithm, using the ReliefF-P algorithm, using REF-CV algorithm and using CFW algorithm, and the classification results were compared and analyzed, and The specific flowchart is shown in Fig. 5. The feature selection algorithm as well as the random forest classifier in this study were performed in python.

Results

PCA dimensionality reduction classification

The original 125-band hyperspectral image data in this study were first classified using RF; after that, the original 125-band was downscaled using the conventional PCA downscaling method, and the first 8 principal components were taken and classified; finally, the 8 principal components obtained using the SS-PCA method were classified; the classification results are shown in Fig. 5. When compared to the outcomes of utilizing PCA classification, which is likewise impacted by the 'the same spectrum but foreign object’, the classification effect for aspen in the original hyperspectral images is poor, and the misclassification into low vegetation is more significant. In this study, in order to verify the effectiveness of SS-PCA, we chose the traditional PCA, Kernel Principal Component Analysis (KPCA), Minimum Noise Fraction Rotation (MNF) and Independent component analysis (ICA), and original hyperspectral image totaling six kinds of hyperspectral dimensionality reduction methods to compare with them, and the classification results are shown in Fig. 6.

In the comparative analysis of dimensionality reduction techniques for hyperspectral datasets, we evaluated the performance of PCA, K-PCA, MNF, ICA and our proposed SS-PCA method. The results, as shown in Table X, demonstrate that SS-PCA consistently outperforms the other methods in terms of overall accuracy (OA), precision, recall, and F-scores across various land cover classes. SS-PCA achieved the highest overall accuracy at 91.98%, outperforming K-PCA (89.82%), PCA (88.25%), MNF (88.17%), and ICA (81.53%). In particular, SS-PCA demonstrated superior performance in challenging land cover types such as buildings, scrubby vegetation, and roads, with F-scores of 94.03%, 88.02%, and 91.76% respectively. While ICA showed exceptional performance in classifying duckweed (with a perfect F-score of 100%), SS-PCA exhibited robust and balanced results across all classes, achieving high accuracy for both vegetation and non-vegetation classes. The superior performance of SS-PCA is likely due to its effective combination of dimensionality reduction and noise suppression, which is critical in handling the complexity of hyperspectral data. Overall, this analysis confirms that SS-PCA is the most effective dimensionality reduction method for enhancing classification accuracy in this study, making it a valuable tool for hyperspectral data analysis.

Comparison of classification accuracy based on different feature combinations

Feature extraction

Several techniques were employed to select features for LiDAR and HSI data, with Table 8 presenting the final selected feature dimensions. Notably, the S-PCA approach, as outlined in section “Features construction”, was utilized to compute the 8 primary component bands from the original hyperspectral data, rather than employing the original bands directly as features. The REF-CV algorithm selected the most features, resulting in 75 dimensions for the LiDAR + HSI feature set. Moreover, the number of features required for modeling significantly decreased after the initial feature screening by the ReliefF-P algorithm, enhancing the model’s generalizability. Lastly, the REF-CV algorithm was employed to identify the best feature subset from the initially screened features. The results indicate that the CFW algorithm effectively eliminated redundant features identified by the ReliefF-P algorithm, resulting in a 20.00% reduction in feature dimensionality.

Classification accuracy analysis

In this study, three optimal feature subsets were extracted using the LiDAR, HSI, and LiDAR + HSI algorithms based on their respective effectiveness and generalizability. Subsequently, the RF classifier was employed to classify the various feature subsets, and the classification accuracy of the different algorithms was compared to identify the best feature extraction model. Figure 9 and Table 9 present the specific classification results.

For the LiDAR data optimal feature subset screening, the best classification accuracy was achieved by 25 features extracted using the CFW algorithm, with an overall correct classification rate of 78.10%. Compared to the original LiDAR features, the overall classification accuracy improved by 3.67%, 2.00%, and 8.33% for the RP algorithm, REF-CV algorithm, and CFW algorithm, respectively. Additionally, the result plots of LiDAR data classification revealed certain misclassifications, such as the misclassification of building eaves as white birch due to similar height differences (Fig. 7a), and the misclassification of undulating roads as scrubby Vegetation (Fig. 7b).

For the HSI data optimal feature subset screening, the RFE-CV algorithm extracted 40 features, achieving the best classification accuracy with an overall correct classification rate of 90.74%. Compared to the original HSI features, the overall classification accuracy increased by 2.78%, 1.30%, and 0.87% for the REF-CV method, RP algorithm, and CFW algorithm, respectively. Examining the HSI data classification result map reveals several misclassification scenarios. Firstly, due to variations in sun angles, some low vegetation and aspens exhibit the same spectrum, leading to misclassification of white birch as scrubby vegetation (Fig. 8a). Secondly, the similarity in surface material between plastic boxes and buildings results in mutual misclassification between the two categories (Fig. 8b). Finally, the similarity in the spectrum between the road and buildings leads to the misclassification of the road as a building (Fig. 8c).

For LiDAR + HSI data, the optimal feature subset screening yielded 54 features using the CFW algorithm, achieving an overall correct classification rate of 97.17%. Compared to the original LiDAR + HSI features, the RP algorithm, and the REF-CV algorithm, the overall classification accuracy improved by 4.68%, 2.30%, and 2.08%, respectively. Furthermore, compared to using hyperspectral or LiDAR data alone, the classification accuracy increased by 7.30% and 19.07%, respectively. The classification results for LiDAR + HSI data (Figs. 9 and 10) demonstrate significantly higher accuracy compared to using LiDAR or HSI data alone. This combined approach effectively mitigates the misclassification scenarios observed previously. By leveraging the spatial and structural features from LiDAR data along with spectral information from HSI data, the classification accuracy is substantially enhanced, leading to more accurate and reliable classification results.

Classification results: (a) the map produced using HSI(Raw features); (b) the map produced using LiDAR(Raw features); (c) the map produced using LiDAR + HSI(Raw features); (d) the map produced using HSI(ReliefF-P); (e) the map produced using LiDAR(ReliefF-P); (f) the map produced using LiDAR + HSI(ReliefF-P); (g) the map produced using HSI(REF-CV); (h) the map produced using LiDAR(REF-CV); (i) the map produced using LiDAR + HSI(REF-CV); (j) the map produced using HSI(CFW); (k) the map produced using LiDAR(CFW); (l) the map produced using LiDAR + HSI(CFW);

Each map is labeled with a serial letter followed by the data type used (HSI, LiDAR, or LiDAR + HSI) and the method applied (Raw features, ReliefF-P, RFE-CV, or CFW).

To evaluate the significance of the differences in classification accuracy among the different methods (Raw data, ReliefF-P, RFE-CV, and CFW), we performed paired sample t-tests. The comparison results of overall accuracy (OA) are presented in the Table 10 below:

Based on the t-test results, we found that the comparisons between most methods are statistically significant (p-value < 0.05), as detailed below: The p-values between Raw data vs ReliefF-P; Raw data vs RFE-CV; Raw data vs CFW; ReliefF-P vs CFW and RFE-CV vs CFW are all less than 0,05, indicating significant differences in classification accuracy. Notably, the p-value between ReliefF-P and RFE-CV is 0.061, which is slightly above the significance level of 0.05, indicating that the difference is not statistically significant but is close.These statistical analysis results suggest that there are significant differences in classification accuracy among the methods used, thereby supporting the stability and robustness of our strategies.

Analysis of feature importance

To explore the importance of features from different data types, feature importance rankings were conducted using the RF classifier for classification. The optimal feature subset with the highest classification accuracy for each data type was selected for this analysis. In Fig. 11, the results indicate that the total weight of intensity features is 0.289, while the total weight of height features is 0.667. Among the intensity features, HAIH_70th has the highest weight, reaching 0.091, while among the height features, IH_10th has the lowest weight at 0.0173. This analysis suggests that, among the LiDAR features, the importance of height features surpasses that of intensity features and nDSM.

Figure 12 illustrates the importance of features from different data types. The analysis reveals that the total weight of vegetation index features is 0.571, followed by S-PCA features at 0.379, and texture features at 0.050. Among the vegetation index features, RENDVI has the highest weight, reaching 0.1, while among the texture features, DOV has the lowest weight at 0.003. This indicates that vegetation index features hold the most significance in terms of classification accuracy compared to SS-PCA features and texture features. Additionally, texture features exhibit the least influence on classification accuracy among the three types of features extracted from HSI data.

Figure 13 provides insights into the importance of features derived from LiDAR and HSI data. The analysis reveals that LiDAR features hold a weight of 0.402, with height features contributing the most at 0.323, followed by intensity features at 0.064, and nDSM at 0.015. On the other hand, HSI features carry a weight of 0.598, with vegetation index features being the most significant at 0.314, followed by S-PCA features at 0.270, and texture features at 0.014. Among the S-PCA features, S-PCA6 exhibits the highest weight at 0.087, while CS has the lowest weight at 0.001. Notably, in the LiDAR + HSI feature set, HSI features outweigh LiDAR features in terms of importance, indicating the greater significance of HSI data for classification accuracy in this combined dataset.

To evaluate potential multicollinearity and identify redundant features, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis(Fig. 14) on the 52 features used in this study. The results show that after applying the CFW for feature selection, high-correlation features were effectively reduced, leaving only those with lower correlation coefficients and important information. However, features related to point cloud intensity and height, such as Hmax, Hmean, and IAIH_60, displayed moderate correlations with coefficients between 0.4 and 0.5 (though not exceeding 0.5), indicating potential redundancy. These features could be considered for consolidation or removal in future iterations to improve model efficiency. In contrast, key vegetation indices like NDVI, LAI, and SR showed weak or near-zero correlations with other features, indicating that they provide unique information relevant to vegetation classification. These were retained to ensure a diverse set of features contributed to the model. This analysis informed our feature selection process, helping to reduce redundancy, mitigate multicollinearity, and improve the overall robustness and accuracy of the classification model.

Verification experiment

The results obtained demonstrate the superior effectiveness of the CFW algorithm in feature extraction, thereby enhancing classification accuracy. To verify the robustness and accuracy of the method, two different types of areas were selected for feasibility validation: Validation Area 1 is an area with a concentration of buildings, acquired at the same location and time as Study Area 1; Validation Area 2, a woodland-concentrated area located in the forested region of Anji County, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, with data acquisition conducted at 11:00 a.m. on March 20, 2023. Validation Area 3 is a public dataset (2013 Houston Data Set), the data set captured over the University of Houston campus and its neighboring regions is used in the experiment. The Houston HSI data set contains 144 spectral bands ranging from 380 to 1050 nm, and each band has 349 × 1905 pixels with 2.5-m spatial resolution. Meanwhile, the corresponding LiDAR data also are the size of 349 × 1905 with the height information of surface materials Features extracted by the CFW algorithm consistently yielded the highest accuracy classification results, as depicted in Table 9 and Fig. 13. These findings underscore the CFW method’s efficacy in efficiently screening features and subsequently enhancing classification results. Given that taller structures and aspen trees dominate Validation Area 1 and are relatively straightforward to identify, LiDAR and HSI achieved commendable classification accuracy. Moreover, the CFW algorithm demonstrated exceptional performance in accurately classifying all features in Validation Area 2, showcasing its capability to deliver superior accuracy. Validation area 3 utilizes a public dataset that includes only DSM data from LiDAR. Therefore, this study does not perform classification using LiDAR data alone. Instead, we applied the Combined Feature Weights (CFW) method to extract features and classify the HSI and HSI + LiDAR data. The final classification result achieved an accuracy of 89.43%, demonstrating the competitive performance of the CFW method compared to some advanced deep learning models. Furthermore, the combination of hyperspectral and LiDAR data yielded even better results, particularly in tree classification.

From the analysis of the three validation areas, it is evident that hyperspectral data consistently achieves higher classification accuracy compared to LiDAR data (Table 11 and Fig. 15). This superiority can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, hyperspectral data capture rich texture, radiometric, and spectral information, providing a comprehensive dataset for classification purposes. Secondly, hyperspectral data extraction typically results in a greater number of spectral features compared to LiDAR, allowing for more detailed feature classification. Thirdly, the analysis of feature importance indicates that hyperspectral features contribute more significantly to classification accuracy than LiDAR features. To further enhance classification accuracy, the CFW method effectively combines multiple types of features to select the optimal subset from a large pool of features. By leveraging the strengths of different data types and selecting the most informative features, the CFW method maximizes classification accuracy and improves the overall performance of the classification model.

Discussion

Hyperspectral dimensionality reduction classification

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) holds promise for ground classification due to its ability to capture detailed spectral information across a large number of narrow spectral bands. However, HSI data often suffers from noise and redundancy, leading to the “Hughes” phenomenon and impacting classification outcomes. PCA-based dimensionality reduction has been a common approach to address these challenges in ground classification tasks. To enhance PCA’s effectiveness in capturing subtle local information from HSI, several improved PCA algorithms have been proposed. Green et al.58 introduced the PCA-based maximum noise transform (MNF), which removes noise from HSI data by applying two PCA transforms in series and sorting images based on quality. Schölkopf et al.59 proposed Kernel PCA (KPCA) to address the complex structure of HSI data and achieve nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Zabalza et al.60 introduced a collapsing PCA algorithm that collapses spectral vectors into a matrix, effectively exploring subtle features in HSI data and improving classification accuracy. Kang et al.61 proposed an algorithm to obtain edge-preserving features (EPF) from HSI and then reduce dimensionality using PCA, achieving improved classification accuracy. In this study, an improved PCA algorithm called S-PCA is proposed, which groups original HSI data based on strong correlations and performs PCA transformation on the grouped data. The results demonstrate that S-PCA effectively extracts both global and fine local information from HSI, leading to improved ground classification accuracy. Specifically, the overall accuracy (OA) is enhanced by 5.48% compared to the original HSI data and by 2.92% compared to conventional PCA methods. However, further investigation is needed to determine the effectiveness of the proposed method for satellite or ground HSI data and whether varying the number of principal component bands in grouped PCA can further enhance classification accuracy.

Comparison of feature extraction methods

Feature extraction methods play a crucial role in mitigating the impact of data redundancy by extracting optimal subsets of features through various algorithms. These algorithms are typically categorized as filtering, wrapper, and embedding methods. Filtering and wrapper algorithms are widely employed, with filtering methods offering advantages such as simplicity, rapid training, independence from mathematical models, and ease of design and understanding. However, they may struggle to effectively eliminate redundant variables due to their reliance on feature relevance for weighting. On the other hand, wrapper algorithms consider feature interactions and can effectively remove redundant variables, although they are more reliant on mathematical models and have higher sample and time complexity for selecting optimal feature subsets. In this study, we demonstrate the effectiveness of both filtering and wrapper feature extraction methods. In LiDAR + HSI data, using ReliefF-P and RF-RFE-CV algorithms improved the classification accuracy by 2.38% and 2.6% (Table 12), respectively, over not applying feature extraction algorithms. These findings corroborate and enhance previous research efforts62,63,64,65, but also underscore the importance of employing representative feature extraction methods to enhance the classification accuracy and amplify spatiotemporal structure information of different land classes.

Two primary categories of feature ablation approach in remote sensing are feature extraction and feature extraction. While numerous features were extracted from LiDAR and HSI data in this study, the abundance of redundant data led to poor classification accuracy. This may be attributed to strong correlations between features, making it challenging to distinguish subtle differences among different land classes, or because certain features were ineffective at distinguishing between different land classes. Narrowing down the feature search space to select the most useful subset from a large pool of features presents a significant challenge16. Although the results of filtering and wrapper algorithms are promising, further research is needed to enhance feature extraction strategies. Therefore, we propose a fusion filtering and wrapper algorithm that deviates from existing methods in terms of its approach, design, and objective. This algorithm aims to effectively address strong feature correlations, select the smallest and most useful feature subset, and enhance classification accuracy. However, additional research is required to determine whether the proposed algorithm can effectively handle ground types with substantial variations in both spectral and structural features. Additionally, variations in terrain, landforms, classifier selection, classification accuracy assessment methodologies, and feature extraction may also contribute to poor classification accuracy and warrant further investigation.

Integration of LiDAR and HSI contributions

HSI data provides valuable spectral information about surface materials that can be distinguished based on their spectral signatures without requiring spatial structure information. However, one challenge with pure spectral analysis is distinguishing between materials with similar spectra or objects that exhibit different spectra. On the other hand, LiDAR data can differentiate between different land cover classes within the same land type at various elevations. Previous research has shown that fusing LiDAR and HSI data can enhance ground classification accuracy. For instance, Hang et al.66 achieved an urban land cover classification accuracy of 88% by integrating LiDAR and multispectral data. Similarly, Bigdeli et al.67 proposed a fuzzy multi-classifier system using fuzzy decision fusion to combine classifiers based on hyperspectral and LiDAR data fusion, resulting in improved classification accuracy.

In this study, we investigated the capability of UAV LiDAR and HSI data to perform combined classification of complex ground types. The results demonstrated that integrating these two datasets significantly improved ground classification accuracy, achieving an overall correct rate of up to 97.21%. This improvement was 18.79% and 6.87% higher than using LiDAR and HSI data individually (optimal feature subset), respectively. This indicates that HSI’s spectral data and LiDAR’s spatial structure data complement each other, allowing for a more detailed characterization of ground classes. Interestingly, we found that spectral features contributed more to ground classification accuracy than LiDAR features, which aligns with previous studies20,22. However, this contrasts with the findings of Zhang et al.68, whose results showed higher LiDAR-based classification accuracy than spectral classification accuracy for urban classification. LiDAR height features (e.g., HAIH_60th, HAIH_99th, Hmean, Hper_99th) provide critical vertical information about different land cover types, enabling the classification model to distinguish between vegetation and structures based on their vertical profiles. Additionally, LiDAR intensity features (e.g., IAIH_60th, IStdDev, IH_30th, IHIQ) offer insights into the surface materials by reflecting the return signal strength from various surfaces. When these height and intensity features are integrated with hyperspectral data, they complement the spectral information by adding spatial and structural details. This fusion of data enhances the model’s ability to accurately classify land cover types, improves edge detection, and introduces a valuable third dimension to the analysis, resulting in more precise and reliable classification outcomes. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in study areas and ground structures. In our study area, where ground structure features were relatively similar, spectral differences played a more significant role, making the combination of LiDAR and HSI more effective for ground classification.

Using the proposed CFW approach for optimal feature subset selection, we identified 25 LiDAR characteristics (including 11 intensity features, 1 nDSM, and 13 height features) and 27 HSI features (including 11 index features, 8 texture features, and 8 S-PCA bands) among the top 52 ideal features. This underscores the greater utility of HSI features compared to LiDAR features for fine-scale ground classification. While our study area was relatively small (8.10 hectares) and yielded promising results, future research could expand the study area and vary ground types to further evaluate the algorithm and feature selection using different datasets.

Conclusion

This study integrates UAV LiDAR and UAV Hyperspectral data and proposes novel algorithms, including the CFW algorithm combining filtered and wrapped algorithms, and an improved PCA dimensionality reduction method based on correlation grouping (SS-PCA). The investigation focuses on multi-source data fusion feature extraction and its application in ground fine classification. The key findings are summarized as follows: (1) the SS-PCA algorithm can effectively improve the classification accuracy (OA = 91.17%), It effectively reduces noise in hyperspectral data and increases the number of effective dimensionality reduction feature bands. (2) The CFW algorithm effectively screens optimal feature subsets for different feature types, thereby enhancing classification accuracy. In crop-intensive areas, the classification accuracy of LiDAR + HSI data reaches 97.17%; in building-concentrated areas, it reaches 97.86%; and in tree-concentrated areas, it reaches 94.28%. (3) Combining LiDAR and HSI data effectively enhances ground fine classification accuracy, mitigating issues such as the ‘salt and pepper noise’ and scenarios involving ‘the same spectrum but foreign object’ and ‘the same objects but different spectrum’ (4) Among single features, LiDAR intensity features play the most crucial role in improving classification accuracy. Among single class features, HSI features are the most important contributors to enhanced classification accuracy. The classification results show that methods integrating hyperspectral and LiDAR data have significant advantages in distinguishing between land use types and specific species. For example, the identification of different tree species provides valuable information for monitoring forest composition and health. At the same time, the differentiation of varying land use types is important for urban planning and agricultural practices. These results demonstrate the value of our chosen categories in practical applications. By integrating spectral and spatial information and optimally weighting features, our framework addresses the challenges associated with high-dimensional data and improves classification accuracy. The comprehensive evaluation and statistical validation of our method further underscore its robustness and reliability. Compared to state-of-the-art techniques, including deep learning models, our approach offers competitive advantages, particularly in terms of feature selection and dimensionality reduction.

Data availability

LiDAR data and HSI data used for this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

References

Charney, J., Stone, P. H. & Quirk, W. J. Drought in the sahara: a biogeophysical feedback mechanism. Science 187, 434–435. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.187.4175.434 (1975).

Schirpke, U., Leitinger, G., Tappeiner, U. & Tasser, E. SPA-LUCC: Developing land-use/cover scenarios in mountain landscapes. Ecol. Inform. 12, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.09.002 (2012).

Talukdar, S. et al. Land-use land-cover classification by machine learning classifiers for satellite observations—a review. Remote Sens.-Basel 12, 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12071135 (2020).

Wolter, P. T., Johnston, C. A. & Niemi, G. J. Land use land cover change in the U.S. Great Lakes Basin 1992 to 2001. J Great Lakes Res. 32, 607–628. https://doi.org/10.3394/0380-1330(2006)32[607:LULCCI]2.0.CO;2 (2006).

Pauleit, S. & Duhme, F. Assessing the environmental performance of land cover types for urban planning. Landscape Urban Plan 52, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00109-2 (2000).

Hansen, M. C. & Loveland, T. R. A review of large area monitoring of land cover change using Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 122, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2011.08.024 (2012).

Foody, G. M. Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 80, 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(01)00295-4 (2002).

Mallupattu, P. K. & Sreenivasula Reddy, J. R. Analysis of land use/land cover changes using remote sensing data and GIS at an urban area, Tirupati India. Sci. World J. 2013, e268623. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/268623 (2013).

Liu, E. et al. Identification of plant species in an alpine steppe of Northern Tibet using close-range hyperspectral imagery. Ecol. Inform. 61, 101213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101213 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Deep learning-based classification of hyperspectral data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 7, 2094–2107. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2329330 (2014).

Hong, S. M. et al. Monitoring the vertical distribution of HABs using hyperspectral imagery and deep learning models. Sci. Total Environ. 794, 148592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148592 (2021).

Rellier, G., Descombes, X., Falzon, F. & Zerubia, J. Texture feature analysis using a gauss-Markov model in hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 42, 1543–1551. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2004.830170 (2004).

Thenkabail, P. S. et al. Selection of hyperspectral narrowbands (HNBs) and composition of hyperspectral twoband vegetation indices (HVIs) for biophysical characterization and discrimination of crop types using field reflectance and hyperion/EO-1 Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 6, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2013.2252601 (2013).

Rodarmel, C. & Shan, J. Principal Component analysis for hyperspectral image classification. Surv. Land Inf. Syst. 62, 14 (2002).

Oldeland, J. et al. Combining vegetation indices, constrained ordination and fuzzy classification for mapping semi-natural vegetation units from hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 1155–1166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2010.01.003 (2010).

Guo, X. et al. Regional mapping of vegetation structure for biodiversity monitoring using airborne lidar data. Ecol. Inform. 38, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2017.01.005 (2017).

Cobby, D. M., Mason, D. C. & Davenport, I. J. Image processing of airborne scanning laser altimetry data for improved river flood modelling. ISPRS J Photogramm. 56, 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2716(01)00039-9 (2001).

Michałowska, M. & Rapiński, J. A review of tree species classification based on airborne LiDAR data and applied classifiers. Remote Sens.-Basel 13, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13030353 (2021).

Hänsch, R. & Hellwich, O. Fusion of multispectral LiDAR, hyperspectral, and RGB data for urban land cover classification. Ieee Geosci. Remote Sens. 18, 366–370. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2020.2972955 (2021).

Buján, S. et al. Land use classification from lidar data and ortho-images in a rural area. Photogramm. Rec. 27, 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9730.2012.00698.x (2012).

Sankey, T., Donager, J., McVay, J. & Sankey, J. B. UAV lidar and hyperspectral fusion for forest monitoring in the southwestern USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 195, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.04.007 (2017).

Dalponte, M., Bruzzone, L. & Gianelle, D. Tree species classification in the Southern Alps based on the fusion of very high geometrical resolution multispectral/hyperspectral images and LiDAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 123, 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2012.03.013 (2012).

Chandrashekar, G. & Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 40, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2013.11.024 (2014).

Huang, R. & He, M. Band selection based on feature weighting for classification of hyperspectral data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. 2, 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2005.844658 (2005).

Ren, J. et al. Partitioned relief-F method for dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral images. Remote Sens.-Basel 12, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12071104 (2020).

Demarchi, L. et al. Recursive feature elimination and random forest classification of natura 2000 grasslands in lowland river valleys of Poland based on airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR data fusion. Remote Sens.-Basel 12, 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111842 (2020).

de Almeida, C. T. et al. Combining LiDAR and hyperspectral data for aboveground biomass modeling in the Brazilian Amazon using different regression algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111323 (2019).

Viinikka, A., Hurskainen, P., Keski-Saari, S. et al. Detecting European aspen (Populus tremula L.) in boreal forests using airborne hyperspectral and airborne laser scanning data. Remote Sens.-Basel 12, 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12162610 (2020).

Gitelson, A. A., Merzlyak, M. N. & Chivkunova, O. B. Optical properties and nondestructive estimation of anthocyanin content in plant leaves. Photochem. Photobiol. 74, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074%3c0038:OPANEO%3e2.0.CO;2 (2001).

Kaufman, Y. J. & Tanre, D. Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 30, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1109/36.134076 (1992).

Gitelson, A. A., Zur, Y., Chivkunova, O. B. & Merzlyak, M. N. Assessing carotenoid content in plant leaves with reflectance spectroscopy. Photochem. Photobiol. 75, 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1562/0031-8655(2002)0750272ACCIPL2.0.CO2 (2002).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8, 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(79)90013-0 (1979).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00096-2 (2002).

Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J. & Merzlyak, M. N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 58, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(96)00072-7 (1996).

Crippen, R. E. Calculating the vegetation index faster. Remote Sens. Environ. 34, 71–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(90)90085-Z (1990).

Boegh, E. et al. Airborne multispectral data for quantifying leaf area index, nitrogen concentration, and photosynthetic efficiency in agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 81, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(01)00342-X (2002).

Haboudane, D. et al. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 90, 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2003.12.013 (2004).

Chen, J. M. Evaluation of vegetation indices and a modified simple ratio for boreal applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 22, 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/07038992.1996.10855178 (1996).

Bernstein, L. S., Jin, X., Gregor, B. & Adler-Golden, S. M. Quick atmospheric correction code: algorithm description and recent upgrades. Opt. Eng. 51, 111719. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.OE.51.11.111719 (2012).

Pettorelli, N. et al. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 503–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.011 (2005).

Rondeaux, G., Steven, M. & Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 55, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(95)00186-7 (1996).

Gamon, J. A., Peñuelas, J. & Field, C. B. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 41, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(92)90059-S (1992).

Merzlyak, M. N., Gitelson, A. A., Chivkunova, O. B. & Rakitin, V. Y. U. Non-destructive optical detection of pigment changes during leaf senescence and fruit ripening. Physiol. Plant. 106, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3054.1999.106119.x (1999).

Sims, D. A. & Gamon, J. A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 81, 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00010-X (2002).

Gamon, J. A. & Surfus, J. S. Assessing leaf pigment content and activity with a reflectometer. New Phytol. 143, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00424.x (1999).

Roujean, J.-L. & Breon, F.-M. Estimating PAR absorbed by vegetation from bidirectional reflectance measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 51, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(94)00114-3 (1995).

Birth, G. S. & McVey, G. R. Measuring the color of growing turf with a reflectance spectrophotometer1. Agron. J. 60, 640–643. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1968.00021962006000060016x (1968).

Huete, A. R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 25, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(88)90106-X (1988).

Broge, N. H. & Leblanc, E. Comparing prediction power and stability of broadband and hyperspectral vegetation indices for estimation of green leaf area index and canopy chlorophyll density. Remote Sens. Environ. 76, 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(00)00197-8 (2001).

Vogelmann, J. E., Rock, B. N. & Moss, D. M. Red edge spectral measurements from sugar maple leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 14, 1563–1575. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431169308953986 (1993).

Peñuelas, J. et al. The reflectance at the 950–970 nm region as an indicator of plant water status. Int. J. Remote Sens. 14, 1887–1905. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431169308954010 (1993).