Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the relationships between hoarding behaviors, autism characteristics, and demographic factors in adults diagnosed with high-functioning ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder). A total of 112 adults, aged 18–35, with high-functioning ASD completed self-reported assessments on hoarding (Savings Inventory-Revised; SI-R) and autism traits (Autism-Spectrum Quotient; AQ). Additionally, demographic data was gathered. Correlation and regression analyses were performed. The findings revealed positive correlations between hoarding and overall autism traits. Autism quotient scores accounted for 24% of the variance in hoarding inventory scores. Higher AQ scores were associated with increased SI-R scores. Specific AQ subscales were linked to particular SI-R subscales. Gender, age, education level, and employment status were connected to assessment scores. A multiple regression analysis revealed that demographic variables accounted for 19% of the variance in hoarding severity. Gender was found to moderate the impact of age on hoarding behaviors. Significant associations were identified between hoarding tendencies and autism traits in adults with ASD. Demographic variables also played a role in symptom presentation. These findings shed light on the relationship between autism characteristics and hoarding behaviors, as well as how external factors influence them. Further research is necessary to enhance understanding and guide interventions for hoarding in ASD populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hoarding disorder is characterized by persistent difficulty in discarding possessions, regardless of their actual value, leading to the accumulation of excessive items that clutter living spaces and impede their intended use. This disorder affects approximately 1.5–6% of the general population1 and often results in significant distress or impairment in personal, familial, social, or occupational functioning2. Although hoarding disorder has been extensively studied in the general population, there is growing recognition of its prevalence and unique manifestations among individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

ASD is defined by difficulties in social communication and the presence of restrictive, repetitive behaviors and interests. High-functioning autism (HFA), a term previously used to describe individuals with ASD who have average to above-average intellectual abilities, continues to pose significant challenges in daily life despite cognitive strengths. These individuals, often previously diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, experience persistent social and behavioral difficulties that impact their overall functioning2.

Among individuals with ASD, hoarding behaviors are particularly prevalent, with studies indicating rates as high as 30–40%, compared to just 2–5% in neurotypical populations3. The co-occurrence of hoarding behaviors in this group is believed to stem from shared rigid cognitive styles and challenges in emotional regulation, core characteristics of both ASD and hoarding disorder4. However, there remains a limited understanding of how these symptoms manifest and what specific functional correlates exist in high-functioning individuals with ASD.

The implications of hoarding behaviors in individuals with HFA are significant, often leading to social isolation, heightened anxiety, and depression5. The factors contributing to these behaviors are complex and multifaceted. For example, individuals with HFA frequently experience sensory processing difficulties, executive function deficits, and repetitive behaviors, all of which may play a role in the development of hoarding tendencies6. Additionally, cognitive rigidity and decision-making challenges are thought to contribute to the persistence of hoarding behaviors in this population7.

Research has identified several factors that may contribute to the prevalence of hoarding behaviors in individuals with HFA. These include higher levels of harm avoidance and lower levels of reward dependence compared to neurotypical individuals8, as well as difficulties with emotional regulation and increased anxiety and depression5. The relationship between hoarding behaviors and other ASD symptoms is complex and often reciprocal; for example, hoarding may exacerbate social anxiety and avoidance, further reinforcing the behavior9. Sensory processing difficulties may also play a role, as individuals with HFA may be drawn to specific textures, smells, or sounds associated with certain objects7.

Despite the significance of hoarding behaviors in individuals with HFA, there is a paucity of research exploring their clinical implications and underlying mechanisms. Moreover, few studies have specifically examined effective interventions for addressing hoarding behaviors in this population. Existing research has predominantly focused on Western contexts, leaving a gap in understanding how cultural factors may influence the expression and management of hoarding behaviors in individuals with ASD in non-Western settings. Given the cultural diversity in behavioral norms and healthcare practices, there is a pressing need for research that explores these behaviors in non-Western contexts to enhance the generalizability of findings and inform culturally appropriate interventions.

Hypotheses

This study aims to address these gaps by exploring the relationship between hoarding behaviors and ASD traits in a sample of high-functioning adults with autism in Egypt, a non-Western cultural context. We hypothesize that:

-

1.

Individuals with HFA will exhibit significant hoarding behaviors, with specific ASD traits, such as cognitive rigidity and difficulties with emotional regulation, being positively correlated with hoarding severity.

-

2.

Demographic factors, including age, gender, and education level, will be significantly associated with the severity of hoarding behaviors, with gender and educational level expected to moderate the relationship between ASD traits and hoarding.

-

3.

The findings will provide insights into the cultural factors that influence the expression of hoarding behaviors in individuals with HFA in a non-Western context.

This study will contribute to the limited body of literature on hoarding behaviors in individuals with ASD, particularly in non-Western settings, and will offer valuable information for developing culturally sensitive interventions.

Methodology

This cross-sectional correlational study aimed to investigate hoarding behaviors in adults diagnosed with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Egypt. We employed validated measures and robust statistical methods to explore the relationships between autism traits and hoarding behaviors within this population.

Participants

Participants were recruited in collaboration with autism support organizations and clinical services across various regions of Egypt, including The Advance Society for Persons with Autism in Cairo, Autism Treatment Centers at Al-Azhar University Hospitals, and Regional Disability Centers in governorates such as Cairo, Giza, Mansura, and Assiut. Recruitment occurred from September 2021 to March 2022, with data collection from October 2021 to April 2022.

To determine eligibility, participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Aged between 18 and 35 years.

-

2.

A formal clinical diagnosis of high-functioning autism spectrum disorder or Asperger’s syndrome, confirmed through clinical records from licensed healthcare providers.

-

3.

Fluency in Arabic.

Participants with intellectual disabilities, bipolar disorder, psychosis, or other major psychiatric or medical conditions were excluded to ensure that the findings specifically reflected the relationship between ASD traits and hoarding behaviors without confounding influences from other conditions. This exclusion criterion, while necessary for internal validity, may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader ASD population, including those with comorbid conditions.

Out of 167 individuals initially screened, 127 met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 15 declined to participate due to personal reasons, such as lack of time or transportation difficulties, resulting in a final sample size of 112 participants. All participants completed the study without any dropouts during data collection. Recruitment strategies were designed to ensure a diverse sample in terms of gender, educational background, and employment status.

Measures

Hoarding behaviors were assessed using the Savings Inventory-Revised (SI-R), a 23-item self-report questionnaire that measures clutter, difficulty discarding items, and excessive acquisition. Higher scores indicate more severe hoarding symptoms.

Autism traits were measured using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), a 50-item self-report scale developed by Baron-Cohen et al.10. The AQ assesses five domains: social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication, and imagination.

Procedure

Upon obtaining informed consent, participants attended an in-person session where they completed the SI-R and AQ questionnaires. Additionally, trained researchers conducted semi-structured interviews to gather qualitative data about participants’ experiences with hoarding behaviors and their relationship to autism traits. The interviews used open-ended prompts to explore participants’ perspectives. Data collection sessions were held in quiet, private rooms at the recruitment sites, specifically designed to minimize distractions and create a comfortable testing environment. All procedures were approved by the Al-Azhar Institutional Review Board. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis

SI-R and AQ scores were analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize the central tendencies and variability in hoarding behaviors and autism traits within the sample. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations between these variables, while t-tests and ANOVAs were employed to analyze group differences based on demographic factors. Multiple linear regression was used to identify demographic predictors of hoarding severity. Additionally, a moderation analysis via hierarchical regression tested whether gender moderated the effect of age on hoarding behaviors.

Qualitative data from the interviews were coded and analyzed using thematic analysis, which helped identify patterns and themes related to the motivations and impacts of hoarding within the context of autism. This mixed-methods approach provided a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between ASD traits and hoarding behaviors.

Community involvement statement

A director of one of the recruitment sites reviewed and provided feedback on the study questionnaires and focus group questions before the study’s implementation. However, no other members of the autistic or broader autism communities were involved in the development, implementation, or interpretation of this study.

Limitations

This study’s reliance on self-report measures, while providing valuable insights, carries inherent limitations, including the potential for response biases and the challenge of accurately capturing complex behaviors through self-assessment. Additionally, the exclusion of participants with certain comorbid conditions may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader ASD population. Future research should consider using a more inclusive sample and employing objective behavioral assessments to complement self-report data.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 112 participants are as follows: 71.4% were male, and 28.6% were female. Regarding age distribution, 46.4% were between 18 and 25 years old, with 26.8% in both the 26–30 and 31–35 age groups. Educational attainment varied, with 35.7% having a high school diploma, 39.3% having some college education but no degree, and 17.9% holding a bachelor’s degree. Employment status showed that 44.6% were employed full-time, 17.9% part-time, and 37.5% were unemployed (see Table 1).

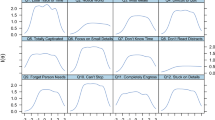

The average scores and standard deviations for the assessment measures administered to the participants are detailed in (Table 2). The SI-R total mean score of 32 suggests moderate levels of hoarding symptoms on average. Among the SI-R subscales, Difficulty Discarding had the highest mean score of 12, followed by Clutter at 11, and Acquiring at 9. For autism traits measured by the AQ, the total mean was 35, which is typical for ASD populations. The Attention to Detail subscale had the highest mean score at 10, followed by Switching Attention at 8, while the Social Skills, Communication, and Imagination domains had lower mean scores ranging between 5 and 7. The standard deviations varied from 2 to 12, indicating some diversity but relatively narrow variation around the means.

Data analysis

Group comparisons and hypothesis testing

The analysis revealed significant gender differences in hoarding tendencies. Specifically, females had significantly higher SI-R total scores than males (p = 0.01), with a moderate effect size (d = 0.40), indicating a meaningful distinction in hoarding behaviors between genders. Regarding age, a one-way ANOVA showed that older age groups had slightly higher SI-R scores compared to younger participants (p = 0.04), although the effect size was small (r = 0.02). These findings suggest that age has a minor but noticeable impact on hoarding severity.

In terms of education, the analysis revealed a significant relationship between educational attainment and autism traits. Participants with lower levels of education had higher AQ scores (p = 0.01), with a moderate effect size (ηp2 = 0.11). This finding suggests that education level may influence the severity of autism traits, with less educated individuals exhibiting more pronounced ASD characteristics (Table 3).

Associations between demographics and assessment scores

When investigating the connections between demographic variables and assessment outcomes, gender emerged as the strongest predictor of hoarding tendencies, while education was the most significant predictor of autism traits. Age had a weaker association with hoarding symptoms. Specifically, higher levels of education were associated with lower SI-R total scores, indicating a negative correlation between education and hoarding severity. Similarly, advanced age was negatively correlated with AQ total scores, suggesting a decrease in autism traits over time. Full-time employment was also negatively correlated with AQ scores, indicating that individuals with stable jobs exhibited fewer autism characteristics (see Table 4).

Associations between specific hoarding behaviors and autism traits

Further analysis revealed specific connections between distinct hoarding behaviors and autism traits. The strong association between SI-R Clutter and AQ Attention to Detail suggests that individuals with a heightened focus on details are more likely to experience difficulties with clutter. The positive relationship between SI-R Difficulty Discarding and AQ Social Skills implies that individuals with better social skills may find it easier to discard items. Additionally, the correlation between SI-R Acquiring and AQ Communication suggests that better communication skills may be linked to a reduced urge to acquire possessions (see Table 5).

Predictors of hoarding severity

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify demographic predictors of hoarding severity (SI-R total score). The analysis showed that gender, age, and employment status were significant predictors of hoarding severity, with gender having the strongest effect (β = 0.21). Specifically, females, older individuals, those with lower education levels, and those with part-time or no employment were more likely to exhibit higher hoarding symptoms. The full model explained 19% of the variance in SI-R scores, indicating that these demographic factors are significant contributors to hoarding severity (R2 = 0.19, F(4,107) = 6.12, p < 0.001) (see Table 6).

Moderation effects

Finally, the analysis tested whether gender moderated the relationship between age and hoarding severity. The results indicated a significant interaction effect, showing that the negative relationship between age and SI-R scores was stronger for males than for females. This suggests that age impacts hoarding behaviors differently across genders (see Table 7).

Discussion

This study investigated the correlation between autism traits and hoarding behaviors in adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The key findings demonstrate a significant relationship between these traits, with ASD characteristics accounting for 24% of the variance in hoarding symptoms. These results contribute to the growing body of evidence that hoarding behaviors are notably more prevalent in individuals with ASD compared to the general population11. Additionally, this study provides insights into the roles of demographic factors such as gender, age, and education in influencing hoarding severity.

Key findings and comparison with prior research

The study’s finding that autism traits are significantly associated with hoarding behaviors aligns with previous research. For instance, Magnuson and Constantino (2011) reported moderate correlations between the severity of autism traits and hoarding tendencies12, while Tolin et al. (2008) observed similar associations between rigidity, repetitive behaviors, and hoarding in children with ASD13. This study extends those findings to an older, high-functioning adult population, indicating that these tendencies persist across the lifespan. However, the predictive power of ASD traits in our study (24%) was lower than the 38% found by Storch et al.2, which may be due to differences in methodology. Storch’s study included observational data, which could capture aspects of hoarding behaviors not fully captured by self-report measures, such as the SI-R used in this study.

In terms of demographic influences, higher levels of education were linked to reduced hoarding behaviors, consistent with South et al. (2011), who found that lifestyle changes, such as increased independence, can help alleviate hoarding tendencies14. This uggests that individuals with higher education may develop better coping mechanisms, which could reduce cognitive rigidity and improve executive functioning, thus mitigating hoarding behaviors.

Alternative explanations and potential mechanisms

Several mechanisms could explain the relationship between autism traits and hoarding behaviors. Cognitive rigidity, a core feature of ASD, may make it difficult for individuals to discard possessions, as they may become fixated on the perceived value or necessity of objects15. Sensory sensitivities common in ASD might also drive hoarding, as individuals may accumulate objects that provide specific sensory experiences16. Additionally, individuals with ASD often experience difficulties with emotional regulation, which may lead them to form strong attachments to objects that offer comfort during emotional distress17.

The observed gender differences in hoarding behaviors, with females exhibiting more severe symptoms, may reflect broader patterns of internalizing behaviors in women with ASD, such as anxiety and depression, which are known to exacerbate hoarding18. Furthermore, the finding that older individuals exhibited fewer hoarding behaviors suggests that these tendencies may decline over time as individuals gain more life experience and develop improved coping strategies19.

Limitations of assessment measures in non-western contexts

One of the limitations of this study is the use of self-report measures, such as the SI-R and AQ, which were developed and validated primarily in Western populations. These tools may not fully capture the expression of hoarding behaviors in non-Western contexts like Egypt, where cultural factors, including attitudes toward material possessions and family obligations, may shape hoarding behaviors in different ways20. Future research should focus on validating these instruments in non-Western populations or developing culturally sensitive tools that better reflect local norms and values.

Future research directions

To further understand the relationship between hoarding behaviors and ASD traits, future research should incorporate longitudinal designs to track the development of hoarding symptoms over time. Longitudinal studies could help identify critical periods during which interventions might be most effective. Additionally, neuroimaging studies could provide insights into the neural mechanisms underlying hoarding behaviors in individuals with ASD, potentially revealing brain regions or networks involved in cognitive rigidity, emotional attachment, or sensory processing.

There is also a need for the development and evaluation of intervention approaches tailored specifically for individuals with ASD who exhibit hoarding behaviors. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be effective in addressing cognitive rigidity and enhancing emotional regulation, but interventions should be adapted to account for the unique cognitive and sensory profiles of individuals with ASD. Furthermore, it is essential to design interventions that are culturally sensitive and applicable in non-Western contexts, ensuring that treatment strategies are aligned with local cultural values and practices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tolin, D. F et al. Neural mechanisms of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69(8), 832–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1980

Storch, E. A. et al. Hoarding in youth with autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: incidence, clinical correlates, and behavioral treatment response. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46(5), 1602–1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2687-z (2016).

South, M., Dana, J., White, S. E. & Crowley, M. J. Failure is not an option: risk-taking is moderated by anxiety and also by cognitive ability in children and adolescents diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1021-z (2011).

Dozier, M. E. & Ayers, C. R. The etiology of hoarding disorder: a review. Psychopathology 50(5), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479235 (2017).

Crane, L., Goddard, L. & Pring, L. Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 13(3), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309103794 (2009).

Masi, A., DeMayo, M. M., Glozier, N. & Guastella, A. J. An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neurosci. Bull. 33(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-017-0100-y (2017).

Lai, M. C. et al. Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism 21(6), 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671012 (2015).

Gillberg, C. & Billstedt, E. Autism and Asperger syndrome: coexistence with other clinical disorders. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 102(5), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102005321.x (2000).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 (2011).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J. & Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471 (2001).

Nutley, S. K. et al. Hoarding symptoms are associated with higher rates of disability than other medical and psychiatric disorders across multiple domains of functioning. BMC Psychiatry 22(1), 647. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04287-2 (2022).

Magnuson, K. M. & Constantino, J. N. Characterization of depression in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 32(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e318213f56c (2011).

Tolin, D. F., Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., Gray, K. D. & Fitch, K. E. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 160(2), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008 (2008).

South, M., Larson, M. J., White, S. E., Dana, J. & Crowley, M. J. Better fear conditioning is associated with reduced symptom severity in autism spectrum disorders. Autism. Res. 4(6), 412–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.221 (2011).

Goldfarb, Y., Zafrani, O., Hedley, D., Yaari, M. & Gal, E. Autistic adults’ subjective experiences of hoarding and self-injurious behaviors. Autism 25(5), 1457–1468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361321992640 (2021).

Balasco, L., Provenzano, G. & Bozzi, Y. Sensory abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders: a focus on the tactile domain, from genetic mouse models to the clinic. Front. Psychiatry 10, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01016 (2020).

Day, T. N., Mazefsky, C. A. & Wetherby, A. M. Characterizing difficulties with emotion regulation in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 96, 101992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2022.101992 (2022).

Napolitano, A. et al. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: Diagnostic, neurobiological, and behavioral features. Front. Psychiatry 13, 889636. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.889636 (2022).

Bratiotis, C., Muroff, J. & Lin, N. X. Y. Hoarding disorder: Development in conceptualization, intervention, and evaluation. Focus 19(4), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20210016 (2021).

Hussain, N. M. et al. Translating and validating the hoarding rating scale-self report into Arabic. BMC Psychol. 11 (1), 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01277-1 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions Mohamed Abouzed: Conceptualization, , analysis, interpretation, writing - original draft, and final approval.Amgad Gabr: Conceptualization, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing - original draft, and final approval.Khaled Elag: Conceptualization, , analysis, , writing - original draft, and final approval.Mahmoud Soliman: Conceptualization, , analysis, interpretation, writing - original draft, and final approval.Nisrin Elsaadouni: Conceptualization, data collection, analysis, , writing - original draft, and final approval.Nasr Abou Elzahab:, data collection, analysis, interpretation, , and final approval.Mostafa Barakat: Conceptualization, , analysis, , writing - original draft, and final approval.Ashraf Elsherbiny:, data collection, , interpretation, writing - original draft, and final approval.A.Aljadani :, final approval and last data analysis and last writting .All authors contributed equally to this study and have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abouzed, M., Gabr, A., Elag, K.A. et al. The prevalence, correlates, and clinical implications of hoarding behaviors in high-functioning autism. Sci Rep 14, 28471 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75371-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75371-8