Abstract

Leveraging diverse optomechanical and imaging technologies for precision agriculture applications is gaining attention in emerging economies. The precise spatial detection of plant objects in farms is crucial for optimizing plant-level nutrition and managing pests and diseases. High-resolution remote sensors mounted on drones have been increasingly deployed for large-scale crop mapping and field variability characterization. While field-level crop identification and crop-soil discrimination have been studied extensively, within-plant canopy discrimination of crop and soil has not been explored in real agricultural farms. The objectives of this study are: (i) adoption and assessment of spectral unmixing for discriminating crop and soil at within-plant canopy level, and (ii) generation of benchmark terrestrial and drone-based hyperspectral datasets for plant or sub-plant level discrimination using various spectral mixture modelling approaches and sources of endmembers. We acquired hyperspectral imagery of vegetable crops using a frame-based sensor mounted on a drone flying at different heights. Further, several linear, non-linear, and sparse-based spectral unmixing methods were used to discriminate plant and soil based on spectral signatures (endmembers) extracted from different spectral libraries prepared using in situ or field, ground-based, and drone-based hyperspectral imagery. The results, validated against pixel-to-pixel ground truth data, indicate an overall crop-soil discrimination accuracy of 99–100%, subject to a combination of endmember source and flying height. The influences of different endmember sources, spatial resolution as indicated by flying height, and inversion algorithms on the quality of estimated abundances are assessed from a verifiable and functionally relevant perspective. The generated hyperspectral datasets and ground truth data can be used for developing and testing new methods for sub-canopy level soil-crop discrimination in various agricultural applications of remote sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agriculture has been undergoing large-scale transformations in the way the crops are monitored and mapped periodically. Thanks to the commercial availability of a host of sensing, monitoring, and intriguing technologies, the practical applications of farming based on the principles of precision agriculture, even in countries of developing economies, are increasingly becoming viable. Specific type of crop monitoring1, detection2,3, and identification of types, phenology, and discrimination have been pursued using various types of optomechanical and electrical imaging technologies. Pursuing further the evolving domain of automation in crop monitoring and management, finer-level spatial detection of crop material at the plant level has recently been attempted4,5. Detection and spatial segregation of crop plant material—detecting leaves, canopy gaps, and soil exposure at the plant level are vital for adapting technological interventions for plant-level optimization of nutrients and pest-disease management. High-resolution RGB and multispectral remote sensing data have been used for large-scale crop mapping and characterization6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 within the field variability for machine-initiated intervention. For example, ultra-high resolution RGB sensors have been used in several cases for biomass estimation14,15. However, RGB sensors are limited by their spectral range, whereas hyperspectral sensors provide contiguous spectral data16, that is essential for the discrimination of various endmembers. Thus, hyperspectral sensors are more suitable for spectral unmixing problems.

With appropriate spectral imaging sensors, drones have the potential to serve as valuable sources of intelligence for detecting and mapping crop attributes at the within-plant canopy levels. Automatic crop-soil discrimination at the plant level is vital for developing automated crop sensing and monitoring solutions at the field or patch level. There have been several studies that report on crop-soil discrimination using high-resolution remote sensing data at the field level17,18,19,20,21,10,22,23. Approached by spectral indices-based differentiations, analyst-assisted, pixel-level discrimination of crop and soil is a well-explored and tested remote sensing application24,25. However, the possibilities of discriminating crop and soil at the plant level, which is sensitive to canopy gaps and structure, have not yet been reported. The potential of crop-soil discrimination at a sub-pixel level in an automation framework has various applications in precision agriculture. For example, it will be possible to detect and estimate effective canopy cover and compute the optimal dose of fertilizers based on the specific needs of the plant. From a crop management perspective, the general collateral impact of chemical insecticide sprays can be minimized by directing a vision-based spray nozzle to focus only on plant material.

Spectral unmixing is a direct theoretical approach for sub-pixel crop soil discrimination. Drone-based hyperspectral imagery (DHI) opens the possibility to evaluate the potential of crop and soil discrimination at a finer spatial scale. Studies assessing within-plant-level spectral unmixing for crop-soil discrimination using DHI are vital for developing spectral capabilities for automatic plant-level crop-soil discrimination. There have been no studies that report on this vital aspect of precision agriculture requirements. Specifically, experiments that answer the following questions are vital for understanding the theoretical possibilities and their practical realization.

-

(a)

How will the structural complexity of crops and soil affect the abundance estimation?

-

(b)

What is the correlation between the abundance estimated using various endmembers sources from an independent field spectral library and various imagery sources?

-

(c)

In a natural landscape scenario, how does spatial resolution impact the accuracy of abundance estimation in multi-resolution DHI?

To investigate and enhance the comprehension of crop–soil discrimination at the plant, we acquired multiple hyperspectral datasets at varying spatial resolutions using a hyperspectral imager mounted on a terrestrial and drone platform and captured under natural illumination conditions. The specifics of the experimental configuration are outlined in the next section, while the outcomes of separating the obtained benchmark hyperspectral imaging via a semi-empirical assessment from a proof-of-concept (PoC) standpoint are presented in the “Results” and “Discussion” sections.

Materials and methods

Forming part of the global developments in researching the methods for vision-based precision agriculture applications, this work has assessed the prospect of automatic discrimination of soil and crops at the plant level by setting up a field- experiment. The major elements in the experimental setup are (i) crop cultivation, (ii) drone-based hyperspectral imaging at different heights, and (iii) ground-based hyperspectral imaging and field measurements. A detailed methodological process is shown in Fig. 1.

Study area and crop selection

The experimental setup is laid out in the fields of the University of Agricultural Sciences, Gandhi Krishi Vignan Kendra, (topographically located at 13° 5.262′ N 77° 33.982′ E) Bangalore, Karnataka, India. The location of the site in India, including a field photograph of a portion of the field, is shown in Fig. 2. Generally, in the southern regions of India, there are two crop cycles: June to October is the Kharif season, and January to May is the Rabi season. The data required for this study was collected at the end of the Rabi season from 04th to 07th May 2018. Based on the extensive cultivation and consumption patterns we selected the cabbage crop to discriminate against soil. The cultivar of the cabbage crop was chosen based on the typical local farmer’s preference for their regular farming.

Data acquisition and pre-processing

We acquired hyperspectral imagery in the reflectance mode from two different sensors mounted on a ground-based platform and on a drone (Fig. 3; included in the appendix I). The ground-based hyperspectral imagery was acquired at the finer spatial resolution of 5 mm. The drone-based hyperspectral imagery was acquired at different heights above the crop canopy. We describe the various sensors used, techniques of data acquisition, and pre-processing in the following subsections.

Terrestrial hyperspectral imaging

The VNIR hyperspectral imager (Make: Headwall, USA; Model: A-Series) is a ground-based hyperspectral imager that can be mounted on a tripod. This imager has 854 spectral bands in the 400–1000 nm wavelength range, and it uses a push-broom mechanism with 1004 pixels in a single column. The rotation stage enables the linear and angular moment of the sensor, thereby acquiring spatially continuous hyperspectral imagery as required. This entire setup was controlled using a laptop computer. To avoid the radiance signal saturation problem in the acquired imagery, we focussed the imager connected to a lens of 23° field of view on a barium sulphate plate (white reference) and fine-tuned the radiance signal levels. The acquired radiance imagery was converted into reflectance imagery by normalizing the radiance with the white reference panel26. The local noise in the reflectance imagery was minimized using the Sav-Gol filter27. The true colour composite of the terrestrial hyperspectral imagery (THI) is shown in Fig. 4a.

Drone hyperspectral imaging

Drone-based hyperspectral imagery was acquired using a compact hyperspectral imaging system (Make: Cubert, Germany; Model: Firefleye S 185). The hyperspectral sensor used in this imager has 125 spectral channels with a 4 nm sampling interval in the 450–950 nm electromagnetic spectrum. The sensor was placed on a quadcopter drone, and data was acquired at different heights: 20 m, 25 m, 30 m, and 40 m, as shown in the synoptic view Fig. 4. The collected radiance image is normalized using the white reference panel. The true colour composite of normalized DHI is shown in Fig. 5a, and the representative spectral profiles, i.e. endmember spectra of the crops from the DHI at heights 20 m and 40 m in Fig. 5b and c.

Field or in-situ reflectance measurements

In addition to the image-based measurements, we acquired in-situ or field reflectance spectral measurements over several locations in the crop field covering cabbage plants and soil. For this, we used a ground-based hyperspectral spectroradiometer (Make: SVC; Model: HR1024i). This instrument can record radiance in the range of 350–2500 nm with a spectral resolution of 3 nm. We maintained a distance of 50 cm over the cabbage plant with a 4° field of view (FoV) of the lens. Reflectance spectral measurements were acquired simultaneously over a white reference panel coated with barium sulphate (BaSO4) for calibrating the radiance spectral measurements. The field reflectance spectral measurements thus obtained were then spectrally resampled to match the spectral range and bandwidth of the ground-based and drone-based hyperspectral imagery. The resampling process was performed by estimating the sensor response function (SRF) of the source sensor, assuming a Gaussian distribution for a given band. When the spectral coverage of the target sensor lies within the wavelength range of the source sensor, the resampling is done by convolving with the estimated SRF and the source spectral data for each channel of the target sensor as described in28.

Figure 6 (presented in the appendix I) presents sample reflectance of the crops and soil acquired from the field spectroradiometer. The field point spectral signatures, and terrestrial and drone hyperspectral imaging were carried out between 10:00 to 13:00 h (local time) on a sunny day. For ease of ingestion in the inversion process of spectral unmixing, the reference reflectance spectra extracted from the terrestrial hyperspectral imager and drone-based hyperspectral imager were organized in the form of a reference database generally known as a ‘spectral library’. Spectral library is a data storage form used by the global remote sensing community for storing and sharing the reflectance spectral data acquired from in-situ or laboratory-based measurement activities. For this work, the database was organized and used as the source of endmember spectra during the inversion processes and statistical/quantitative validation of the various unmixing algorithms. This library would serve as a standard reference spectral library in future research activities, should one choose to study the same endmembers. To enable assessing the impact of the multiple resolutions in the spectral unmixing, reference reflectance spectra from the drone-based imagery were acquired at two different heights: 20 m, and 40 m called DHI20 and DHI40, respectively, in this work.

Spectral unmixing models

Each pixel in the terrestrial or drone hyperspectral imagery can be broadly classified into two categories: a pure pixel that contains cabbage crop/soil or a mixed pixel that contains both components. Since the quality of spectral unmixing is a function of the inversion method used, we applied nine different spectral unmixing methods, such as linear29,30, non-linear31, and sparse32,33 based inversion methods for an exhaustive assessment. We provide a brief description of the mathematical information.

The sensor reaching signal, \({y}_{i},\left(i\in\left\{1,2,3,\dots.n\right\}\right)\), can be represented as:

where, \({e}_{i,c}\) and \({e}_{i,s}\) represent the spectral value of the endmembers cabbage crop and soil in the \({i}^{th}\)- channel; \({a}_{c}\) and \({a}_{s}\) are the fractional abundances of the cabbage and soil, and \({\eta}_{i}\) is the noise caused by the scattering effects in the path between the ground and the sensor, as well as internal sensor noise. Extending Eq. (1) for a full hyperspectral imagery, \(\varvec{y}=\left[{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\dots.{y}_{p}\right]\), we get the following representation:

where \(\varvec{a}=\left[{a}_{c},{a}_{s}\right]\) is the abundance matrix corresponding to its endmembers \(\varvec{e}={\left[{e}_{i,c},{e}_{i,s}\right]}^{T}\) and \(\varvec{\eta}=\left[{\eta}_{1},{\eta}_{2},\dots.{\eta}_{p}\right]\) is the noise matrix.

The spectral unmixing is a constraint problem wherein the abundance must be either positive or zero, generally known as abundance non-negativity constraint (ANC) (implying \(\varvec{a}\boldsymbol{\ge}\mathbf{0}\)) and the sum of all the abundances must be equal to one, known as abundance sum constraint (ASC) (implying \(\mathbf{1}^{\varvec{T}}\varvec{a}=\mathbf{1}\)). This can be mathematically expressed as a constraint least square (CLS) problem, and a fully constraint least square (FCLS) problem:

To enable the use of endmembers from the external spectral library built using the field reflectance spectral measurements, we rewrite Eq. (3) as a sparse regression problem as follows:

where \({\left\|.\right\|}_{2}\) and \({\left\|.\right\|}_{1}\) are \({\ell}_{2}\) and \({\ell}_{1}\) norms, respectively; λ is a controlling parameter between the two norms. In Eq. (5), \(\lambda=0\) implies CLS; imposing ASC in the same equation results in the FCLS. The sparse regression problem can be solved by the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM)34.

The collaborative sparse unmixing problem33 is mathematically expressed in the Eq. (6), where \({\left\| X \right\|}_{F}\) is Frobenius norm and regularization parameter \(\lambda>0.\)

In Eq. (6), \(\sum_{k=1}^{m}{ \left\|{\varvec{a}}^{k} \right\|}_{2}\) is ℓ2,1 mixed norm, which provides the sparse solution.

The above interaction models are strictly single interaction models, where, for simplicity, the multiple interactions with different materials and/or within the material are not accounted for. To account for the multiple interactions at the material level, a non-linear mixture model is suggested31. The non-linear model considers a possibility of the secondary light interaction in addition to the primary interaction that is considered in the linear model. The Fan bilinear model is mathematically represented as follows:

where, \({\varvec{a}}_{m}\in{a}_{c},{a}_{s};\)\({\varvec{a}}_{m}{\varvec{a}}_{n}\) is the abundance generated through the second-level interaction of both the endmembers of \({\varvec{e}}_{m}\) and \({\varvec{e}}_{n}\) (\({\varvec{e}}_{m},{\varvec{e}}_{n}\in{\varvec{e}}_{c},{\varvec{e}}_{s}\)), \(\odot\) represents the Hadamard product (i.e., component-wise product). The extension of the Fan bilinear model is the generalized bilinear model with an additional parameter \({\varvec{\gamma}}_{mn}\in\left[\mathbf{0},\mathbf{1}\right]\), a parameter used for the reconstruction of spectra, expressed as follows:

To model the higher-order interactions of light there is a polynomial post-non-linear model (PPNM). The PPNM model is a two-phase model - first, it performs the basic LMM, and in the second phase, it models the nonlinearities by adding additional terms to the LMM as represented in Eq. (9).

PPNM and bilinear models deal with the interaction of light with the surfaces and do not account for the loss of energy due to surface reflection or absorption of the material. To account for the energy loss, we used another model of spectral mixing called the multilinear mixing model (MLMM) given as follows:

The models presented in Eq. (1) through Eq. (10) are based on the interactions of light with other or within materials, but the aspect of the directionality of light is overlooked. Considering these directional interactions, the Hapke intimate mixture model35 considers the incoming (θi) and outgoing (θo) radiation in cosine terms and the single scattering albedo (ω) of the medium with respect to the surface normal and wavelength and is expressed as follows.

To estimate the abundances in the hyperspectral imagery, the reflectance data and endmember have to be transformed from the reflectance space to the albedo space, given as follows:

Albedo refers to the ratio of integrated bi-hemispherical outgoing radiation to the incoming radiation. In the context of the intimate mixture modelling framework for spectral unmixing, it is considered that the different objects interact at the microscopic level, which is modelled by Hapke in the albedo domain, rather than the reflectance domain. Further, Hapke considers the dependence of the mixing on single scattering albedo (ratio of outgoing radiation to the incoming radiation as a function of viewing angle). This treatment of mixing at macroscopic levels as a function of single scattering albedo allows to incorporate the effect of topography at the endmember level, thus allowing a more sophisticated and realistic modelling of the non-linear spectral unmixing.

Validation and quantitative analysis

Multiple different metrics are used in the evaluation of the quality of unmixing in various hyperspectral unmixing applications. The widely used metrics are Signal Reconstruction Error (SRE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The SRE metric, expressed in dB, quantifies the closeness of the hyperspectral imagery synthesised based on the mixture modelling of the finite number of endmembers chosen and the original hyperspectral imagery by a chosen algorithm. Higher values of SRE indicate better reconstruction quality. Responding to the local variations within a scene-context assessment, RMSE, also called spatial RMSE (S-RMSE) allows the evaluation of the quality of spectral unmixing by quantifying the differences between spectra of synthesized pixel and ground truth spectra.

The signal reconstruction error (SRE) metric was used for validation at the overall imagery level and is given as follows.

where, \(\varvec{Y}\) denotes the input hyperspectral image and \(\widehat{\varvec{Y}}\) denotes the reconstructed hyperspectral image. The pixel-wise (spatial) root mean squared error (S-RMSE) computed between \(\varvec{Y}\) and \(\widehat{\varvec{Y}}\) and was computed using the following Eq.

In this equation, \(\varvec{y}_{{p}_{i}}\) and \(\widehat{\varvec{y}_{{p}_{i}}}\) represent ground truth and reconstructed pixel spectrum, respectively.

We define the overall – RMSE (O-RMSE) as the average of the entire image S-RMSE.

Taking advantage of the availability of the ground truth spectral data acquisitions and plant-level measurement of canopy and soil fractions, we assessed the quality of spectral unmixing by signal reconstruction using SRE and RMSE and the comparison of the estimated abundances with actual abundance values computed during the field data acquisitions.

Results and analysis

In this section, we present the results of crop-soil discrimination in terms of the abundance of cabbage and soil from the terrestrial and drone-based hyperspectral imagery using imagery and an independent or external field spectral library source.

Case 1: abundances from terrestrial hyperspectral imagery (THI)

The abundances of the cabbage and soil when the sources of endmembers were THI, and field reflectance spectral libraries are presented in Fig. 7a and Table 1. The corresponding estimation of error at the pixel level is shown in Fig. 7b. As evident from Table 1, for the field reflectance spectral library, the maximum retrieval percentage of the abundance for the cabbage crop and soil is 86% and 99%, respectively. By the methods considered, the overall performance of linear unmixing algorithms is robust and superior as compared to the non-linear spectral unmixing algorithms, although both underestimate the abundances. The maximum level of accurate abundance estimates for the field-based spectral library source is produced by the linear algorithms (around 86%). Although, in the non-linear category of algorithms used in this paper, the MLMM algorithm can achieve an accuracy of around 85%, the performance of the other algorithms has substantial variations. In the case of soil, both the linear and non-linear algorithms produce satisfactory results as the accuracy level of the estimated abundances remains above the 98% mark. CLS and SUnSAL overestimate the soil abundances, while MLMM marginally outperforms all the other algorithms with an accuracy of around 99%.

In the case of the THI-based spectral library, the maximum retrieval percentage of abundances for cabbage crop is substantially higher (94%), while exhibiting almost similar retrievals for soil (97%). In contrast with the results observed with field reflectance spectral library source, the non-linear algorithms produced consistently better results (accuracy level of around 92 to 94%). For THI based spectral library, the HAPKE spectral unmixing model yielded the best estimate of the abundance of cabbage crop at 93%. The overall accuracy of the abundance estimates for soil, using both linear and non-linear algorithms using a THI-based spectral library, is marginally lower compared to a field-based spectral library. The S-RMSE computed pixel-wise between the input hyperspectral image and reconstructed image from abundance and endmembers is shown in Fig. 7b. The statistical distribution of pixel-wise reconstruction error is depicted in Fig. 7c. As evident by the overall trends, the error distribution for the field-based library source is, overall, uniform and concentrated around the mean value peak, while for the THI-based spectral library source, it has spread moderately, possibly caused by the increased levels of noise in the reconstruction phase. In addition, the peak indicating the maximum error shifts upward for the field-based library source (indicating more peak error) compared to the THI-based library source. The RMSE analysis, shown in Fig. 8a, shows that CLS, SUnSAL in the linear and PPNM, and MLMM in the non-linear category of spectral unmixing algorithm produce satisfactory results compared to the other algorithms used in this paper. The maximum SRE ratio of 23.37 and 25.14 is obtained using the field-based spectral library and THI-based spectral library, respectively, as shown in Fig. 8b.

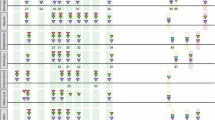

Case 2: abundances from the multi-resolution drone-based hyperspectral imagery (DHI)

Areal abundances of cabbage crop and soil estimated for DHI of various spatial resolutions using in situ or field reflectance and image-based spectral libraries (THI, DHI20, and DHI40) are graphically represented in Fig. 9 and visually shown in Fig. 10. The overall results suggest that the spatial resolution of the target imagery has a substantial bearing on the accuracy of the abundance estimate. We observe that as the spatial resolution gets coarser (as the flying height changes from 20 m to 40 m), the accuracy of the cabbage crop abundance estimate reduces across all the input spectral libraries and algorithms. Also, the general trend from the results indicates that the abundance estimate of soil is relatively more accurate than that of cabbage crop, possibly owing to the structural complexity of the crop compared to soil. The structural complexity, as related to this work, is the distinct shape or lack of it for a crop type. Further, the image-based spectral endmember source used for estimating abundances yields superior results than the field spectral source consistently across all the algorithms and for all different spatial resolution target imagery.

For the field-based spectral library, the accuracy of estimated abundances of cabbage crop using linear algorithms such as FCLS and CLSUnSAL algorithms (~ 88%) is comparatively better than the non-linear algorithms. For the cabbage crop, there is a systematic initial drop in the quality of abundance estimation, observed across all the algorithms considered, as the target imagery gets spatially coarser, i.e., when the flying height increases from 20 m onwards. However, it is interesting to note that there is a considerable improvement in the accuracy of abundance beyond imagery acquired by 30 m flight for all the cases and algorithms considered in this paper. The increased accuracy for the imagery acquired beyond 30 m flight suggests that the algorithms stabilize their performance after the initial drop in accuracy possibly caused by the intricate structural complexity of the cabbage crops. In contrast, for the case of abundance estimation of the soil using the field-based spectral library, the performance of non-linear unmixing algorithms is superior to the spectral unmixing algorithms. The abundances from the MLMM, PPNM, and HAPKE models are in the range between 99 and 100% which can be deemed satisfactory compared to other spectral unmixing algorithms. It is worth noting that for this case, all the spectral unmixing algorithms exhibit a maximum error margin of 12%, except for CLS and SUnSAL, which overestimates the abundance estimate ranging from 125 to 132% when compared to the ground truth as the spatial resolution gets coarser.

When using terrestrial hyperspectral imagery (THI) as the spectral library, the discrimination accuracy by different classes of algorithms is like that of the field-based spectral library. The maximum accuracy for the cabbage crop (86%; for the imagery acquired at a flying height of 20 m), is achieved using linear algorithms such as FCLS and CLSUnSAL, while the maximum abundance estimate accuracy for soil (99.95%; for the imagery acquired at a height of 25 m) is achieved the non-linear algorithms such as MLMM and HAPKE. For the assessment of soil abundance estimate, the observed accuracy may be classified into three distinct patterns by using spectral unmixing techniques. In the case of semi-analytical spectral unmixing algorithms, such as PPNM, MLMM, and the HAPKE model, the abundance range spans from 99 to 97%; in the case of the FCLS, CLSUnSAL, GBM, and Fan-BL model, the capacity falls between 81% and 89%, and in the case of the CLS and SUnSAL, an overestimation ranging from 120 to 125% is observed.

For the abundances estimated using DHI20-based spectral library, the overall trends in the performance of the linear algorithms and the non-linear linear algorithms are found to be similar to that of THI and field-based spectral library. We obtain a maximum accuracy rate of 83% for discerning the pure cabbage crop pixel acquired at 20 m flying height by the FCLS and CLSUnSAL algorithms while a soil discrimination accuracy of 99.2% is obtained by the PPNM acquired at 25 m flying height. The PPNM model shows a significant disparity in cabbage crop discrimination, with a worst-case rate of 40.1%. Conversely, the same inversion approach shows a remarkable soil discrimination rate of 99.2%. The observed pattern in the accuracy for the estimation of soil abundance remains consistent with the previous cases, where the non-linear algorithms perform better than the linear spectral unmixing algorithms.

The abundance estimates for the DHI40 spectral library show an interesting pattern. In this case, we observe that the non-linear algorithms have an overall edge in the performance over the linear algorithms for the case of the cabbage crops pixel. With few exceptions, the accuracy of the abundance estimate lies in the range of 90–95%. The improved accuracy may be attributed to the enhanced capability of the non-linear algorithm to capture the non-linear dynamics of the structural complexity of crop/finite-size objects at a coarser resolution. Further, there is no overestimation of abundance estimation for soil by linear algorithms, particularly by the CLS and SUnSAL. The best possible cabbage crop and soil abundance estimate of around 99% accuracy has been obtained using the DHI40 spectral library. Overall, the results from the DHI40-based spectral library have the key implication that an image-based spectral source at a coarser resolution might be a more suitable source for practical spectral unmixing purposes using airborne or remote satellite data.

Figure 10 shows the visualization of the quality of reconstruction via the S-RMSE image between the raw hyperspectral imagery and the reconstructed imagery obtained from the abundance and endmembers. Figure 11 illustrates the statistical distribution of the reconstruction error at the pixel level. The error distribution for the field, THI, and DHI20 library source exhibits a more uniform pattern and is concentrated around the peak of the mean value. In contrast, the error distribution for the DHI40-based library source is more spread out, which may be attributed to higher levels of noise during the reconstruction phase. The overall RMSE analysis, as shown in Fig. 12a, demonstrates that the CLS and SUnSAL algorithms in the linear category, as well as the PPNM and MLMM algorithms in the non-linear category of spectral unmixing, provide acceptable outcomes when compared to the other algorithms used in this study. The inverse relationship between the SRE ratio and the total RMSE is observed in Fig. 12b.

Discussion

Technical advancements in the context of close-range remote sensing areas, such as imaging, platforms, algorithms, etc., are the major driving forces behind the rapidly growing field of precision agriculture and, thus, the agricultural industry. Remote detection and spatial segregation of agricultural plant material, such as leaves, canopy gaps, and soil exposure at the plant level, are essential for plant-level optimization of nutrient uptake and management of plant-level pests and diseases. Several studies in the literature1,9,25,36,37 have typically used different classification algorithms for feature discrimination purposes. While this may be useful for large areas with sufficient spatially delineated class boundaries, it fails in the cases of mixed pixels, shadow pixels, or edge pixels. To this effect, we have used ultra-high resolution spatial-spectral imagery for the quantitative analysis of the crop and soil discrimination using various linear and non-linear spectral unmixing algorithms and different sources of input spectral libraries. The primary goal was to present a remote sensing method for within-plant scale discrimination of crop and soil fractions for potential autonomous sub-canopy level crop sensing by drone-based spectral imaging systems. However, the experimental setup and its implementation have been undertaken expansively to serve as a PoC study from a semi-analytical and semi-empirical approach addressing vital questions in the spectral unmixing of remote sensing imagery. Specifically, this work has attempted to address the following questions aimed at understanding theoretical possibilities and their practical realization.

-

(a)

Compared with the ground truth of the actual abundance of materials in a pixel is available, what is the accuracy of abundance estimate obtained from using various sources of endmembers imagery acquired at different spatial resolutions?

-

(b)

In a natural landscape scenario, how does spatial resolution impact the accuracy of abundance estimation in multi-resolution DHI?

-

(c)

What is the functional relevance of the ‘quality of unmixing’ quantified by statistical error metrics and functional abundance retrievals?

-

(d)

How does the structural complexity of crop and soil affect the abundance estimation?

As apparent from the results, the quality of the abundance estimate is influenced by several factors, such as the structural and chemical composition of the target material, imaging sensors, sources of spectral library, and inversion algorithms, which are discussed below.

Limit of crop–soil discrimination as quantified by abundance estimate

The theoretical considerations expect that the abundance retrievals ought to be 100% for both crop and soil. From practical implementation perspectives, the best abundance retrievals obtained are 99.71% and 100%, respectively, for crop and soil (See Fig. 9). These abundances are obtained from drone imagery. Despite being ultra-high spatial and spectral resolution imagery, the abundance retrievals from THI are 94.4% and 99.67% (see Table 1) for crop and soil, respectively. Even though the differences, when compared with the drone-based or theoretical limits, are only marginal, the observation suggests the non-linear relationship between image resolutions and accuracy of abundances in practical implementations. However, illumination anisotropies at fine resolution (e.g., sub-leaf glint) and horizontal-geometrical resolution changes affected due to oblique imaging typical to ground-based hyperspectral imaging (THI) may also introduce within-canopy spatial-spectral deviations, which in turn reduce the magnitude of abundance retrievals. In contrast, airborne imaging mode, especially with a nadir view, maintains uniform spatial scale and sensor-illumination direction, thereby minimizing the dominance of within-plant glint and heterogeneity of within-image spatial resolution.

Impact of spatial resolution on discrimination

Crop and soil abundance estimation through unmixing is traditionally considered a spectral problem. However, the quality and spatial distribution of spectral anisotropies of landscape elements or discernible objects, especially at high resolutions, introduce within-object spatial and spectral distortions. These distortions, which are within the imagery and object level, introduce spatial resolution as an additional factor in spectral unmixing. Multiple studies have evaluated the quality of spectral unmixing using imagery acquired at a single relatively coarse resolution38,39. Introducing and examining the impact of the differential spatial resolutions on the spectral unmixing, the abundance results obtained from hyperspectral imagery acquired from different flying heights of the drone suggest a complex relationship between the quality of spectral unmixing and spatial resolution. The abundance retrievals for soil are close to 100% with only a marginal deviation. The abundances are of similar magnitude even though different sources of endmembers are used in the inversion modelling (Fig. 13 included in the appendix I). Further, the change in the abundance is marginal (about 5%) across the different spatial resolutions considered. This observation suggests the marginal or no influence of spatial resolution on the quality of abundance retrieval for soil.

For crops, in contrast with soil, the abundances change substantially with spatial resolution. Deviating systematically from the theoretical suggestion of a linear relationship between abundance and spatial resolution, the crop abundance-spatial resolution follows an inverted Gaussian curve. There is the presence of an optimal spatial resolution (e.g., hyperspectral imagery acquired at 30 m height in this study) at which the abundance retrieval is stable across different sources of endmembers. Interestingly, the difference between the highest and lowest abundance values for crops at different spatial resolutions (as indicated by different flying heights of drone) is the same (about 25%). The results suggest that spectral features for crops are dynamic within the scene as imaged at different spatial resolutions.

Impact of endmember sources

The endmembers and their related parameters, such as the source of endmembers, number of endmembers, and quality, are dominant factors influencing the accuracy and robustness of abundance estimates. In contrast to the studies in the literature, which have used endmembers from the candidate imagery using various endmember extraction algorithms36,40, we have assessed the potential of using external spectral libraries as the source of endmembers, in addition to the use of the endmembers extracted from the candidate imagery based on ground truth. For the drone-based hyperspectral imagery acquired at different heights, aka spatial resolutions, the abundance estimates for crop obtained from using endmembers from close-range measurements, i.e., endmembers collected from field, THI, and DHI20, are substantially lower than the ground truth value of 100%. The abundances from all three sources of endmembers are closer and is about 75%. In contrast, the abundance estimates for soil are consistently higher and are approximately closer to the ground truth value of 100% across the different spatial resolutions and sources of endmembers. However, considering the spectral library DHI40, source endmember, which is relatively low resolution, the abundance retrievals for crop and soil are high − 96% for crop and 99.5% for soil (see Figs. 9 and 14). The reason for this may possibly be attributed to the situation that at 40 m flying height, the cabbage and soil endmembers are structurally entangled enough to yield a spectrally mixed source, and the impact of leaf-level illumination or geometrical projections has averaged out. Based on these results with data compatibility and augmentation with imagery, the independent spectral libraries may be useful for large-scale spectral unmixing tasks using either space or airborne HSI applications.

Impact of inversion method used in spectral unmixing

Estimation of abundances compared against actual ground truth measurements at the sub-pixel level is challenging, and there is no open access reference hyperspectral/multispectral imagery with real sub-pixel level ground truth data to date. For this reason, we find that the focus of the research community has been the development of various linear and non-linear spectral unmixing algorithms without much ado to their validation with real-world data39,41. In this study, acquiring imagery and associated sub-pixel ground truth data under natural conditions, an attempt has been made to analyse the patterns of changes in the abundances as a function of inversion algorithms, taking into consideration the different scenarios of varying spatial resolution continuum, and input spectral library (source of endmembers). A summary of the unmixing performance of the different inversion algorithms used is presented in Fig. 15. According to the findings, the overall disparity in abundances between the various inversion algorithms for the cabbage crop is 25%; this is substantial, considering the highest and lowest rates of abundances being around 75% and 96% for the drone-based hyperspectral imagery. The non-linear models, except the PPNM and Hapke model, offer relatively better and uniform performance across the different spatial resolutions of hyperspectral imagery and the spectral libraries (source of endmembers) considered. The direction of abundance changes from different spatial resolutions, by the different methods used, exhibit a distinct pattern - inverted Gaussian curve for seven out of nine methods; two non-linear methods, Hapke and PPNM, exhibit a zig-zag pattern (Fig. 16).

The quality of retrieval of abundance for soil presents a distinct pattern in that the estimates are consistently close to the ground truth value of 100% irrespective of the source of endmembers and method of inversion. A notable exception is an overestimation by a couple of methods out of nine methods, linearly constraint (CLS) and its sparse variant (SUnSAL). When forced to follow the sum-to-unity constraint, the abundance estimates from these two methods also approach the ground truth value. Further, the apparent deviation, even though minimal by absolute magnitude, is due to close-range endmember sources. Notwithstanding the variation of abundance for crop and soil, the results from the HAPKE model present a distinct pattern – while the abundance for crop varies substantially, the abundance for soil is stable and is high across the different sources of endmembers and imagery used (Fig. 15). This observation indicates that an intimate mixture model (e.g., the HAPKE model) offers excellent performance in the abundance retrieval of materials that are intimate mixtures or of particulate structures and lack individual geometrical shapes. Plant, being a tangible geometrical shape object, affects anisotropic spectral interaction at the sub-pixel level that cannot be captured by an intimate mixture model.

Functional relevance of error metrics as quality metrics in practical unmixing applications

There are two distinct perspectives of functional relevance in assessing the possibility and quality of spectral unmixing as viewed from the endmembers and the type of unmixing at the level of material-radiation interaction. First, the closeness of abundance estimates to the actual sub-pixel fractions is considered as direct ground truth. This view enables assessment of the functional application of the abundances estimated and the quality of retrievals benchmarked against verifiable data. The second view is an abstract understanding of the closeness of the reconstructed imagery to the original imagery. Except for a few studies that have used simulated imagery, most of the studies on spectral unmixing, including this study, have used statistical error measures, SRE, and O-RMSE (see Eq. 13) for assessment and benchmarking of the quality of spectral unmixing results. Our results present a distinct case of reviewing the relevance of using the error metrics, pointing out the deficit in correlating the ‘numerical’ quality assessment with functional abundance estimates. For example, the quality of spectral unmixing as indicated by SRE for the Hapke model is poor, with a value of about 10 compared to the mean SRE observed across the inversion algorithms used in the experiments. By theoretical interpretation, the value of abundance estimated at different flying heights (as indicated by different sources of endmembers) ought to be low and similar. However, as evident from the actual abundance estimates (see Fig. 9), the change in abundance is enormous (varying from 5 to 86%). Further, the pixel-level distribution of O-RMSE (Fig. 12), computed as spatial RMSE (S-RMSE) in this study, indicates a remarkable pattern; the RMSE distribution has spread systematically across the range of RMSE and encompasses all the levels of intensity values reconstructed. Based on these patterns of SRE and O-RMSE, it is expected that the abundance estimates ought to be poor. However, as evident from Fig. 9, the abundances retrieved, consistent across spatial resolutions, indicate fairly good values and are not substantially lower than the estimates from the other methods. This observation suggests that measuring the quality of spectral unmixing by metrics (e.g., SRE, RMSE), which provide only the overall imagery quality metric, is inadequate to assess the spectral unmixing functionally using real-world imagery. We, therefore, recommend a review of the current mechanism used for quality assessment of spectral unmixing and for developing pixel-level error capture mechanisms for practical applications.

Conclusions

Within-plant canopy discrimination of soil and crop fraction is vital for the targeted handling of crops in precision agriculture with the aid of remote sensing data. Forming part of the assessment of broad prospects for developing a remote sensing-based approach for crop-soil discrimination within a plant canopy, we have performed multi-pronged research on the conceptual advancement of spectral unmixing.

This is the first of its kind of work that attempted to understand the functional relevance of spectral unmixing from the perspective of data from multiple sensors at multiple resolutions acquired in a natural environment. We acquired multi-sensor (various platforms, terrestrial and drone) and multi-resolution (various spatial resolutions of drone flying at different heights) hyperspectral imagery datasets that include precise ground truth measurements of crop and soil abundances. The reference datasets generated in this research are very helpful for researchers in studying various methodological issues in spectral unmixing. By undertaking point-to-point level validation of abundance estimates based on a reference level, the outcomes provide novel perspectives on the broader issue of spectral unmixing, as outlined below.

-

With due consideration of the source of endmembers, it is possible to differentiate within-plant areal fractions of crop and soil from drone-based imagery as evident with close to 100% accuracy of the discrimination of cabbage and soil fractions.

-

As viewed from the source of endmembers, the quality of abundances estimated in the drone-based imagery, across the different imagery resolutions and inversion algorithm used, from the close-range hyperspectral imagery (THI and DHI at low flying height) is comparable with that of the in situ or field spectral measurements.

-

Generalizing the influence of factors related to spatial resolution and endmembers on the quality of abundances, the source of endmembers as indicated by the level of measurement platform, exerts a stronger influence compared to the spatial resolution of the imagery.

-

The influence of spatial resolution on the quality of abundance estimates is only marginal to moderate on soil (0–10%) but substantial over the crop (25–50%), especially from the intimate mixture-based unmixing model.

-

The best abundance estimates for crop are obtained from the combination of coarse-resolution imagery and endmembers extracted from coarse-resolution imagery.

-

The widely used statistical methods (e.g. SRE and RMSE) for performance assessment of the spectral unmixing are not suitable for functional application. We recommend the application of pixel-level ground truth-based methods for performance validation.

Data availability

The authors will be glad to share the data used in this work with any academic researchers free of charge. We encourage interested researchers to contact the corresponding author (E-mail: rao@iist.ac.in).

References

Cuaran, J. & Leon, J. Crop monitoring using unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. Agric. Rev. https://doi.org/10.18805/ag.R-180 (2021).

Suchi, S. D., Menon, A., Malik, A., Hu, J. & Gao, J. Crop Identification based on remote sensing data using machine learning approaches for Fresno County, California. In IEEE Seventh International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications (BigDataService) 115–124 (IEEE, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/BigDataService52369.2021.00019

Wu, F., Wu, B., Zhang, M., Zeng, H. & Tian, F. Identification of crop type in crowdsourced road view photos with deep convolutional neural network. Sensors 21, 1165 (2021).

Aznar-Sánchez, J. A., Velasco-Muñoz, J. F., López-Felices, B. & Román-Sánchez, I. M. An analysis of global research trends on greenhouse technology: Towards a sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 664 (2020).

Kavga, A., Thomopoulos, V., Barouchas, P., Stefanakis, N. & Liopa-Tsakalidi, A. Research on innovative training on smart greenhouse technologies for economic and environmental sustainability. Sustainability 13, 10536 (2021).

Yang, N. et al. Large-scale crop mapping based on machine learning and parallel computation with grids. Remote Sens. 11, 1500 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Large-scale and high-resolution crop mapping in China using sentinel-2 satellite imagery. Agriculture 10, 433 (2020).

Yan, S. et al. Large-scale crop mapping from multi-source optical satellite imageries using machine learning with discrete grids. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 103, 102485 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Large-scale crop mapping from multisource remote sensing images in Google earth engine. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 13, 414–427 (2020).

Moumni, A. & Lahrouni, A. Machine learning-based classification for crop-type mapping using the fusion of high-resolution satellite imagery in a semiarid area. Scientifica 1–20 (2021).

Turkoglu, M. O. et al. Crop mapping from image time series: Deep learning with multi-scale label hierarchies. Remote Sens. Environ. 264, 112603 (2021).

Alami Machichi, M. et al. Crop mapping using supervised machine learning and deep learning: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 44, 2717–2753 (2023).

Khan, H. R. et al. Early identification of crop type for smallholder farming systems using deep learning on time-series sentinel-2 imagery. Sensors 23, 1779 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Remote-sensing estimation of potato above-ground biomass based on spectral and spatial features extracted from high-definition digital camera images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 198, 107089 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Estimating potato above-ground biomass by using integrated unmanned aerial system-based optical, structural, and textural canopy measurements. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108229 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Improving potato above ground biomass estimation combining hyperspectral data and harmonic decomposition techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 218, 108699 (2024).

Apan, A. A. et al. Spectral discrimination and separability analysis of agricultural crops and soil attributes using ASTER imagery. 17 (2002).

Viscarra Rossel, R. A. & Webster, R. Discrimination of Australian soil horizons and classes from their visible-near infrared spectra. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 62, 637–647 (2011).

Andújar, D. et al. Discriminating crop, weeds and soil surface with a terrestrial LIDAR sensor. Sensors 13, 14662–14675 (2013).

Falco, N. et al. Influence of soil heterogeneity on soybean plant development and crop yield evaluated using time-series of UAV and ground-based geophysical imagery. Sci. Rep. 11, 7046 (2021).

Misbah, K., Laamrani, A., Khechba, K., Dhiba, D. & Chehbouni, A. Multi-sensors remote sensing applications for assessing, monitoring, and mapping NPK content in soil and crops in African agricultural land. Remote Sens. 14, 81 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Soil nutrient estimation and mapping in Farmland based on UAV imaging spectrometry. Sensors 21, 3919 (2021).

Hashemi-Beni, L., Gebrehiwot, A., Karimoddini, A., Shahbazi, A. & Dorbu, F. Deep convolutional neural networks for weeds and crops discrimination from UAS imagery. Front. Remote Sens. 3, 755939 (2022).

Xue, J. & Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. J. Sens. 1–17 (2017). (2017).

Le, N. T., Apopei, V., Alameh, K. & B. & Effective plant discrimination based on the combination of local binary pattern operators and multiclass support vector machine methods. Inf. Process. Agric. 6, 116–131 (2019).

Guo, A. et al. Identification of wheat yellow rust using spectral and texture features of hyperspectral images. Remote Sens. 12, 1419 (2020).

Savitzky, A. & Golay, M. J. E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 36, 1627–1639 (1964).

Van der Meer, F. D. & De Jong, S. M. Imaging Spectrometry: Basic Principles and Prospective Applications Vol. 4 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Keshava, N., Kerekes, J., Manolakis, D. & Shaw, G. An algorithm taxonomy for hyperspectral unmixing. 22 (2000).

Keshava, N. A survey of spectral unmixing algorithms. Linc. Lab. J. 14, 55–78 (2003).

Heylen, R. & Scheunders, P. A multilinear mixing model for nonlinear spectral unmixing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 240–251 (2016).

Iordache, M. D., Bioucas-Dias, J. M. & Plaza, A. Sparse unmixing of hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 49, 2014–2039 (2011).

Iordache, M. D., Bioucas-Dias, J. M. & Plaza, A. Collaborative sparse regression for hyperspectral unmixing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 341–354 (2014).

Bioucas-Dias, J. M. & Figueiredo, M. A. T. Alternating direction algorithms for constrained sparse regression: Application to hyperspectral unmixing. (2012). https://arxiv.org/abs/1002.4527 Math.

Hapke, B. Theory of Reflectance and Emittance Spectroscopy (Cambridge University Press, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139025683

Li, Z. et al. Subpixel change detection based on radial basis function with abundance image difference measure for remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 13, 868 (2021).

Nguyen, C. T., Chidthaisong, A., Kieu Diem, P. & Huo, L. Z. A Modified bare soil index to identify bare land features during agricultural fallow-period in Southeast Asia using Landsat 8. Land 10, 231 (2021).

Bhatt, J. S. & Joshi, M. V. Deep learning in hyperspectral unmixing: A review. In IGARSS 2020–2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 2189–2192 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS39084.2020.9324546

Cavalli, R. M. Spatial validation of spectral unmixing results: A systematic review. Remote Sens. 15, 2822 (2023).

Zaman, Z., Ahmed, S. B. & Malik, M. I. Analysis of hyperspectral data to develop an approach for document images. Sensors 23, 6845 (2023).

Shao, Y., Lan, J., Zhang, Y. & Zou, J. Spectral unmixing of hyperspectral remote sensing imagery via preserving the intrinsic structure invariant. Sensors 18, 3528 (2018).

Funding

This work was part of the Indo-German research cooperation “the rural-urban interface of Bengaluru - a space of transitions in agriculture, economics, and society” funded by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India. We acknowledge the support from DBT in the form of a research grant (DBT/IN/German/DFG/14/BVCR/2019/Phase-II).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.: Implementation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Discussion, Visualization, Writing–original draft. S.S.J.:: Writing–review. R.R.N.: Conceptualization, Funding, Formal analysis, Discussion, Writing–review draft. V.K.D.: Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study has not used data or samples pertaining to any human, animals. No ethical committee approval is required for this study as such. This study has used data acquired on cultivated plants. We would like to declare that the study has complied with all the relevant guidelines applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manohar Kumar, C.V.S.S., Jha, S.S., Nidamanuri, R.R. et al. Precision crop mapping: within plant canopy discrimination of crop and soil using multi-sensor hyperspectral imagery. Sci Rep 14, 24903 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75394-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75394-1