Abstract

Karst represents approximately 15% of the planet’s surface, hundreds of millions of people live on and rely on these aquifers for water supply and agricultural irrigation. In karstic landscapes, groundwater is exposed in sinkholes, inundated caves, and artesian wells, which are two-way communication spots. When the phreatic level is exposed, the groundwater can change substantially as a result of anthropogenic impacts, modifying the water quality and the environmental integrity by incoming excess nutrients, contaminants, pathogens, and other hazardous substances such as metals and microplastics. In this paper, we develop and test a multimetric index to evaluate the condition status of dolines located within urban areas, including seven indicators: trophic index, fecal bacteria, fecal viruses, microplastics, heavy metals, zooplankton biodiversity, and fish biodiversity. Lastly, we made a proof of concept for the index in the dolines on the island of Cozumel (Mexico), resulting in evaluations from fair to good. The index is powerful due to its sensitivity to pathogens and exotic invasive species. This additive weighted index allows to assess the condition status of dolines in urban areas anywhere in the world; if required, modifications are possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Karst is a term widely used to describe the different landscapes developing in areas dominated by limestone, dolomites, gypsum, and halite, where carbonate rocks are dissolved by HCO-saturated water. Karst areas are characterized by scarcity or lack of surface water and the presence of sinkholes and other well defined geomorphological depressions in which surface runoff water and groundwater have local fast exchange, together with all the particulate and dissolved substances present1,2. Karst covers approximately 12 to 15% of the ice-free terrestrial surface of the planet3,4 and it is present virtually everywhere. Large cities rely predominantly or entirely on karst aquifers as water sources5, it is estimated that close to 20–25% of the world’s population rely on groundwater for freshwater supply6. Dolines lakes, regionally known as “Cenotes” in Mexico, are epikarstic expressions in which groundwater comes into contact with the atmosphere owing to the exposure of the water table, namely formed by dissolution and collapse of the rock, commonly one of the diagnostic features in karst landscapes6,7. These epikarstic expressions connect aquifers to terrestrial landscapes; thus, exposed karst aquifers make them particularly vulnerable to contamination by entering and distributing undesirable substances with rapid transfer in groundwater8, it is one of the environments most susceptible to anthropogenic disturbance9. This can cause effects such as the deterioration of water quality, changes in the karstic landscape, ecosystem pollution, and the extinction of rare species10; as such, karst aquifers require monitoring, protection, and management11,12.

Urbanization can be defined as human agglomerations with a surface built greater or equal to 50% of the landscape and population density greater or equal to ten individuals per hectare; but it can also be understood as a multidimensional process or rapid change in patterns of human population and its effect of land cover. Nowadays, urban areas house more than half of the global population, and projections estimate that 70% of the total world population will live in urban areas by 205013. Due to rapid urbanization, karst areas have been subject to land use changes, sometimes with irreversible consequences, and increased ecological risk brought by human interaction14. Prevention and deterrence instead of remediation are desirable because corrective actions are not always feasible15,16,17. It is essential to assess groundwater vulnerability in karstic landscapes and relate them to natural, human-induced and climate change hazards and scenarios18,19,20.

One very useful approach to urbanization’s effects on the environment is the reconstruction of the history (or paleohistory) together with a narrative on the urbanization process21. In some cases, due to the lack of information and the recent process of urbanization, such approaches cannot be used; thus, we explore other alternatives to assess the disassociation of biodiversity, ecosystems, and urban development13. There are environmental indices to evaluate environmental quality, disturbance, sustainability or conservation indices in karst22,23; yet, to the best of our knowledge, not previously including emergent contaminants and communities structure. Even though they do not provide the full story, we obtain a valuable overview of the situation, which helps us to estimate the current condition and outline the proper management strategies. The creation or modification of indices is not unusual. Tailored metrics for specific needs help to prioritize environmental monitoring, management, and restoration actions24. That is why we identify the need for an index tailored for tropical karst features that integrate several parameters, not only related to the environment (commonly water quality), but also health risks, emergent contaminants, and a representation of the biodiversity. This contribution aims to join worldwide efforts on the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) proclaimed by the UN, a call to protect ecosystems for the benefit of people and nature25.

For this index, we have included parameters and indicators representing the trophic state, pathogens, contaminants, and biodiversity. The trophic state scale used for this index is the TRIX, a multimetric index thoroughly used because of its ability to explain the causes and effects of eutrophication26. The bacterial fecal indicators Enterococci and Escherichia coli were used, in addition to three viral fecal indicators such as somatic coliphages, F + specific coliphages, and Pepper Mild Mottle Virus (PMMoV). Coliphages and PMMoV were included as viable indicators for the detection and tracking of fecal pollution in aquatic environments27, including groundwater from karst aquifers28. The PMMoV is frequently detected in sewage-contaminated environments throughout the world27, and can be used as a surrogate for the presence of other viral pathogens that pose a health risk in the population29.

For our purposes, we call contaminants all chemical substances that are present in the environment at levels higher than normal or when those components are not meant to exist in the environment30. Due to urbanization and industrialization, there has been an increasing accumulation of man-made compounds, including metals and plastics. The greatest concern is related to heavy metals, whose common feature is being toxic to the environment and humans31; whereas the increased use of plastic worldwide (together with its incorrect disposition and reduced recycling) is causing plastics to end up as waste reaching the environment32. Many of these plastics undergo physical processes such as breakage and photodegradation, creating small particles of plastic material known as microplastics (MP). The occurrence of MP in water is of growing concern because they have been found virtually in every part of the world33, groundwater included.

The variability of the environmental conditions in tropical aquatic ecosystems determines high biodiversity34. Food webs and interaction with other organisms enrich the ecosystem and contribute to its stability and functioning; any drastic alteration in the ecosystem can cause an imbalance in biological diversity and communities35. For this index, we evaluated the zooplankton and fish communities. Zooplankton is comprised of microorganisms that are essential for maintaining water quality; for example, they have an active role in the degradation of organic matter, control vectors, and are a crucial link in the trophic network36. The use of zooplankton as an indicator of water quality has been applied in freshwater and saline ecosystems37, its presence in the environment is an indicator of good environmental health, despite physical and chemical or seasonality, zooplankton populations are always present, only environmental disturbance and chemical or physical contamination alter irremediably their life cycle, presence and permanence in an ecosystem38,39. Fish can also act as indicators of water and environment of aquatic ecosystems40,41. Fish communities have intrinsic ecological and economic value that contribute to ecological processes; they also play a crucial role in ecosystem services, such as water purification, sediment stabilization, and nutrient cycling regulation. Some species have significant economic value for commercial and tourism (fish watching and diving); thus, these economic activities depend on the preservation of aquatic ecosystems, dolines and karst lakes included.

There are various methodologies and approaches to observe, assess, evaluate, and monitor water quality, not one better than the previous; rather, they answer to different conditions or needs based on the situations occurring in the study area42. Recently, comparisons have been made for water quality, trophic state, and heavy metals indices using expert system (ES) and machine learning (ML) methods43, delineating the way to integrate several assessment models for the evaluation of environmental quality. In this paper, we develop an index to evaluate the Condition Status Index of dolines in urban areas (CSI-D) including seven indicators (TRIX trophic index, fecal bacteria, viral fecal indicators, microplastics, heavy metals, zooplankton and fish biodiversity). The CSI-D was then tested in dolines developing in an urban area on the Island of Cozumel (Mexico) as proof of concept. We propose that this index can be applied to any karst site in the world, including karst sites listed in UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Methods

Analytical methods and index design

The CSI-D is an additive index that integrates several physico-chemical and biological parameters into seven indicators which expresses numerically (from 1 to 4) the ecological condition of each of the studied dolines. The indicators are (1) TRIX trophic class, (2) fecal bacteria (coliforms and E. coli), (3) viral fecal indicators; (4) abundance of microplastics, (5) concentration of heavy metals in the soluble and interchangeable fractions of the sediment, (6) zooplankton diversity and (7) fish biodiversity. Each indicator has four categories, from bad to very good (Table 1), each category with specific criteria to meet different regulations, and guidelines of background values. There are cases where there is no consensual guideline or reference values that can apply in all conditions, such as microplastics or biodiversity. In those cases, the division among categories can rely on previous expert knowledge, previous references with local or regional data, or being a self-evaluated site, that is, considering their own minimal and maximal values for the categorization.

Trophic state

The trophic state was evaluated with the TRIX index44

Integrating the concentration of chlorophyll a (Chl a) measured following Lorenzen45. The dissolved oxygen was measured with Winkler titration and the saturation deviation was computed as D%O2 = 100—%SAT DO. The measured nutrients were dissolved inorganic nitrogen (NO2- + NO3- + NH4+) soluble reactive phosphorous (PO43-), all measured with colorimetric UV–Vis methods. The factors k (-1.5) and m (1.2) are constants that help define the index between values of 0 and 10. We used the TRIX index for the trophic state, which is different from other trophic indices such as the one established by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development46, which considers only chlorophyll a. Modifications to the trophic state estimates can produce different results; yet it can be changed if properly justified.

Fecal bacteria

We quantified fecal coliforms and E. coli as they are the most common fecal bacteria observed in freshwater water quality regulations. Samples were collected in duplicate in sterile 100 ml vials with sodium thiosulfate for chlorine inhibition, using nitrile gloves during the sampling. Samples were filtered through sterile mixed ester (EMC) filter membranes, 0.22 µm pore size, 47 mm diameter, gridded surface, individually packed WHATMAN Cytiva (ME 24/21). The membrane is plated on ReadyPlate™55 Chromocult Coliform Agar. These plates were aerobically inoculated and then incubated inverted at 36 °C (± 2 °C) for 24 h; after incubation, all colonies gave a positive β-D-galactosidase and β-D-glucuronidase reaction (from dark blue to purple) are examined and counted as E. coli. Colonies that give a positive β-D-galactosidase reaction (pink to red) are counted as presumptive non-E. coli coliform bacteria. The results were reported as MPN per 100 mL of water sample. To ensure a correct reading of the results, blanks (Milli Q Type II water) were prepared under aseptic conditions. The detection interval for each 100 ml of sample was 1–5000 colony forming units (CFU) for Total coliforms and 1–3750 CFU for Fecal coliforms (E. coli). Each batch of material has a quality certificate. The categories were established based on the Mexican regulation NOM-001-SEMARNAT-202147, which sets the maximum permissible limit for fecal Enterococcus and E. coli for karst soil in 50 CFU/100 mL as a monthly average.

Viral fecal indicators

Samples were manually collected using sterile 10 L containers. Somatic and F + specific coliphage quantification was performed by the double-layer assay48 using E. coli ATCC CN13 700609 and 15597 as bacterial host strains, respectively. The double-layer assay was performed as described previously by Rosiles-González et al.28. Results were expressed as Plaque Forming Units per 100 ml (PFU/100 ml). The quantification of PMMoV was performed as follows: 10 L water samples were concentrated by the elution-adsorption method28,49. A second concentration step was carried out using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filters following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentrated volumes obtained were between 1990 and 2349 µl. RNA extraction was carried out with the QIAmp viral RNA extraction kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using the Bio-Rad iScript™ Advance cDNA Synthesis kit for RT-qPCR kit, with 5 µl of RNA following the manufacturer´s instructions per reaction. cDNA synthesis was carried out in the SimpliAmp™ thermocycler (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc) at 46 °C for 20 min and 95 °C for 1 min. PMMoV quantification was performed by qPCR using a CFX96 TouchTM Real-Time PCR Detection System thermal cycler. A standard curve was prepared using serial dilutions of the control plasmid (100–105 copies). qPCR reactions were performed in duplicate, using a final volume of 25 µl, with 5 µl of RNA, 12.5 µl of 2 × buffer, 0.4 µl of MgSO4 (50 mM), 1.25 µl of the primers/probe mix (5.0 and 2.5 nmol, respectively) and 0.5 µl SuperScript III/Platinum Taq. PCR-grade water was used as a negative control. For PMMoV quantification by qPCR, primers that amplify a fragment of the capsid gene were used as described by Zhang et al.50. Amplification conditions were 1 cycle at 50 °C for 15 min, 1 cycle at 95 °C for 2 min, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. The estimation of the genome copies per liter (GC/L) of PMMoV was obtained as previously described by Rosiles-González et al., 2017. The categories for the index were established based on PMMoV concentrations detected in previous studies in the area28,51.

Abundance of microplastics (MP)

Microplastics are considered an emerging contaminant52 and one very important indicator of human impacts on aquatic ecosystems53. The collection of the samples was carried out using 500 mL glass bottles. The samples were taken at surface level (20 cm) and were immediately covered to avoid atmospheric contamination. Samples were collected in duplicate at all sites wearing cotton garments to avoid contamination of the samples with synthetic fibers from clothing. The samples were taken to the laboratory at the Water Sciences Unit of the Yucatan Scientific Research Center where they were stored at room temperature for conservation and subsequent analysis. As quality control, we used two field blanks, and 400 ml glass bottles with previously filtered Milli-Q water.

Digestion of organic matter

A digestion of the organic matter was carried out using hydrogen peroxide54. 30 ml of H2O2 was added to the samples55, covered with aluminum foil, and allowed to react for 24 h at room temperature.

Extraction of microplastics

The procedure was carried out 24 h after the digestion of organic matter. Filtration was carried out using a vacuum pump and cellulose Millipore filters with 0.45 µm pore size56. At the end of the filtration, the filters were taken with steel tweezers to quickly place them in Petri dishes internally lined with aluminum foil; once fully closed, the dishes were labeled and stored at room temperature.

Hot needle test

The hot needle test was performed to identify whether the particles had properties of plastic materials. Stainless steel forceps were used, and heated until the tip was red-hot. Then, the particle was exposed to the tweezers on a slide and observed under the microscope to record any change in its physical structure.

Visual identification

Filters were observed at 10 × and 40 × with a microscope OMAX M83EZ-C02; the examination was carried out by quadrants to facilitate the exploration and subsequent position of the particles57. These were classified according to their morphology as a fragment, fiber, foam, sphere, and pellet58. Similarly, the color and size of each particle were recorded. The criteria for the identification of MP are based on Lusher et al.59 such as the absence of cellular or organic structures, homogeneous thickness of the particles, and homogeneous colors and brightness.

Abundance

After the hot needle test and the evaluation of the samples in the blanks, the visually identified results were used to compute PM concentration with the equation:

where MPVis. id. Is the final count of visually identified PM per filter, MPblank is the average number of MP in both blanks, and V is the filtered sample volume. The abundance of MP is expressed as particles per liter. Due to the scarce information about microplastics in groundwater, we applied the self-evaluated principle for this indicator, where the undesirable environmental condition (Bad) was assigned to the quartile with the greatest number of particles. Depending on the largest number, the categories can be set to the percentile most appropriate for any given results.

Heavy metals in sediments

Heavy metals are always a concern regarding sources for drinking water and wildlife protection60, regardless of the source of the dominant economic activities, their presence is frequently undesirable. Sediment sampling and analysis were done as described by Ortega-Camacho et al.61, with composite samples representing sediments from the first 20 cm. To quantify the concentration of heavy metals that might be of greater concern, we performed the first two steps of the sequential extraction method by Tessier62, obtaining the soluble and interchangeable fractions, those of easy liberation into the aqueous medium and their evaluation was based on the maximum permissible limits for metals established in the proper legislation. For this paper, we exemplify the ecologic criteria for water quality for the protection of freshwater aquatic life in Mexico63. The soluble and interchangeable fractions were analyzed by ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Optima 8000). Reactive blanks and a travel blank were used for all test methods. All samples were analyzed in triplicate and data with a relative standard deviation less than 10% are reported. A linear calibration was performed on the equipment with eight external standards, and automatic integration in software (Syngistyx for ICP-OES). The experimental detection limit (0.003 to 0.1 mg/L) was calculated from the average of the analytical blanks and standard deviation in the measurements. The theoretical detection limit or the least concentrated standard can be taken from the calibration curve. The categories were established based on the Mexican Ecological Water Quality Criteria CE-CCA-001/89 for aquatic wildlife protection63. Additional criteria can include that lower evaluation is given to sites with more than one metal above the maximum recommended limit.

Zooplankton biodiversity

The biodiversity of zooplankton was evaluated as species richness per site. It was obtained by surface net trawling with a Wisconsin net of 54 µm mesh size. At each study site, between three and five drags of approximately 1 m were carried out, where the total volume of filtered water (≈ 150 L) was concentrated in 250 mL bottles. Finally, the sample is fixed with 5% formalin. Zooplankton species were identified with dichotomous and pictorial guides64,65. With the species diversity, the zooplankton evaluation considers the largest number of species identified at the lowest taxonomic level as nmax, and the biodiversity at each location as n; thus, it is normalized to the specific diversity found only at the time of collection as n/nmax.

Fish biodiversity

The evaluation criteria considered the relative abundance, divided into dominant (> 20%) with three points, common (5–20%) two point, and scarce (1–5%) one point. The presence of protected species established by the Mexican regulation NOM-059-SEMARNAT-201066 is considered a positive attribute and was given an additional point. Exotic invasive species is a negative attribute; thus, the value of its abundance (from 3 to 1) is subtracted as a penalty when such organisms are found on the site. Null abundance was given 0 points. Fish sampling was done with trap (nasa or Rittel type) and cast net, depending on the ease of access or locating specific places with fish aggregation67. One baited nasa trap was submerged for 10 min (to prevent predation among fish inside the trap) in two locations and all organisms inside the trap were retrieved and photographed; then released. The use of the cast net was specific for the sites where the conditions allowed its launch and it was complementary to capture fish that, due to their size, could not enter the nasa traps. Field identification of the species was carried out by observing in detail the morphological structures of each species, photographs were used in the laboratory of Ecology and Biodiversity of Aquatic Organisms of the UCIA to confirm field identification, using the guides of Robertson et al.68 and Schmitter-Soto67 the lowest possible taxonomic level (specie).

Index description

The CSI-D is an additive index with seven weighted indicators with individual values Ei from 1 (bad) up to 4 (very good; Table 1). The result of each indicator is sited into the respective evaluation category Ei and then is normalized to a sub-index Si per indicator with the equation \({S}_{i}^{n\cdot }=n/7\), where n represents all seven indicators, trophic state (TS), fecal bacteria (B), viral fecal indicators (V), microplastics (MP), heavy metals (M), zooplankton (Zd) and fish diversity (Fd). The highest possible value for each weighted factor Si is 0.57. The CSI-D is then the result of the addition of all Si

Thus, the highest score is 4, very good in all categories, and the lowest is 0, bad in all categories. There might be cases when an indicator cannot be included in the CSI-D; for instance, impossible to collect sediments due to inaccessible sinkhole bottom or safety concerns. In those cases, the general evaluation to integrate the condition status index can consider only the indicators that were collected and calculated and adjust the weighting factors as \({E}_{i}^{n\cdot }=M\), with M the number of indicators included in CSI-D.

Statistical analyses

To assess the most relevant parameters and the similarity among the evaluated sinkholes by the CSI-D, we performed two tests, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and a Hierarchical cluster analysis as supporting analyses of the evaluations made with the multimetric index. Analyses were done with OriginPro69.

CSI-D case study

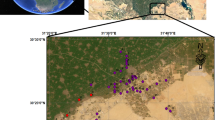

The CSI-D was evaluated in ten dolines in the urban area of Cozumel Island in Mexico (Table 2, Fig. 1). Cozumel is the third largest island in Mexico (647 km2), and the second most populated (88626). It is located at the east of the state of Quintana Roo, Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea (20° 26′ N, 86° 55′ W) with an average altitude of 7 masl. It is characterized by a warm humid climate (Am), a mean annual temperature of 27.7 °C, and annual rainfall of 1400 mm with abundant summer rains70. Physiographically, it is a rocky plain with rocky or hardened floor slopes, dominated by sedimentary limestones and Leptosols71. It is important to highlight that the complete island is a Biosphere reserve designated in 2016; thus, requiring constant water quality monitoring, not only for human health but also for environmental integrity.

Location of the urban sinkholes evaluated in the Island of Cozumel, Mexico. Map generated with QGIS (version 3.34.1-Prizren; https://qgis.org), using spatial layers of information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography72.

Results

Here, we present the results showing the evaluation categories (Ei) and the indicator sub-index Si for each indicator.

The trophic state sub-index SiTS (Table 3), indicates that most of the dolines have a fair to good condition status, only two dolines in very good condition. The fecal bacterial sub-index (Table 4) showed that all dolines are negatively impacted by these organisms (all in bad condition), suggesting the entrance of fecal material. The viral fecal sub-index (Table 5) showed that coliphages (somatic and F + specific) were found at all sites, and PMMoV was found in 90% of the sites, when analyzing the results of the occurrence of the three viral indicators, only one site had very good condition (where PMMoV genomic copies were absent), followed by one site with good condition, 7 sites with fair condition and one site with bad condition. These results suggest that the trophic state of the evaluated dolines in the urban area of Cozumel suggests Fair conditions, but all of them are impacted by fecal material.

The microplastics sub-index shows great variability. First of all, the index evaluated the maximum particle number quantified in this area, it was not referred to any previous reports, given the uncertainty in microplastic concentration worldwide, making it unfair to set a number as the least desirable condition. The number of particles was found between 1 and 50 per liter. The site with the highest presence of microplastics was El Arco; although this site is surrounded almost completely by vegetation (93,000 m2), it is located within the city, subject to surface runoff influence. On the other hand, the site with the lowest number of particles per liter was Helechos, which is also surrounded by vegetation (21,000 m2), but this doline is located on the northeast outskirts of the city, see Table 6.

Considering only this emerging contaminant, a clustering based on its abundance (MDS analysis, Bray and Curtis 75% similarity, 2D stress = 0) reported three groups, A and B composed by Helechos and Royal 2 respectively, due to the lowest abundances of microplastics. Group C includes Caletita, Royal 1, Xkan-Ha, Cuarteria, and Chu-Ha. Lastly, group D includes Arcos and Maravilla, with the highest abundances of microplastics. This grouping is based on the difference in abundance (KW test, p < 0.05). The post hoc pairwise comparisons show that differences were observed between the high and low abundance of microplastic particles per liter (Bonferroni test; p < 0.05).

Regarding the heavy metals sub-index, soluble Fe and Cu were only quantified in one site (Caletita), a location with heavy traffic roads and receiving surface runoff, giving a bad condition. In the exchangeable fraction, we measured metals such as Fe, Mn, Zn, and Al. The most concerning result was for “Arco” sinkhole, where Cd was quantified, immediately imparted a bad condition status. The dolines with Fair conditions reported redox-sensitive elements (Fe, Mn) or Zn at concentrations that are not considered harmful for wildlife protection (Table 7).

Biodiversity was largely dominated by sites in fair condition with four to five identified species; while for fish biodiversity, protected species (desired characteristic) and exotic or invasive species (undesired characteristic) were considered for the evaluation; thus, the condition assessment might be contrasting. There are four important groups of zooplankton (rotifers, ostracods, cladocerans, and copepods). Copepods and rotifers are found at all sites, while ostracods were observed at seven sites, and cladocerans only at one site. Out of the ten sites, the one with the highest number of species is Royal 1, followed by Royal 2, Caletita, and Cuarteria. These sites have a higher salinity and are closer to the coast, compared to the rest of the sinkholes. It is important to mention this because the diversity did not distinguish between freshwater and saline species; thus, it is unable to capture changes in biodiversity due to changes in salinity. The sub-index suggests that Good condition dolines are those with more species (greater richness); thus, Royal 1 would be the most biodiverse, while Arco doline has the lowest number of species (also the one with Cd in the exchangeable fraction in sediments). The other dolines are rated Fair. Cladocerans were only reported in one site (Maravillas), the doline with all four groups of zooplankton indicator; the rest of the dolines had only three out of the four groups of zooplankton. Regarding the fish diversity, six species were recorded, five local species (Poecilia velifera, Gambusia yucatana, Garmanella pulchra Xiphophorus sp., Abudefduf saxatilis) and one invasive species (Oreochromis niloticus) widely distributed in Mexico. It is relevant to note that biodiversity sub-indices were not consistent for these animal groups, and sometimes even contrasting (Arco, Royal 1, Cuarteria), see Table 8.

According to the CSI-D, eight dolines in the urban area of Cozumel obtained a fair general assessment, and two (El Arco and Cuarteria) in Bad condition (Table 9). The index considers equal weighting for all indicators; thus, when one of the sub-indices is harshly evaluated, its value penalizes the general evaluation. This particular situation was observed for fecal bacteria, which add the lowest possible value to the index. If the fecal bacteria are removed, the general evaluation improves to 0.2 or 0.3; yet, its evaluation is still in the middle of Fair. Another important aspect of this evaluation is the categorization of the fish diversity sub-index, where the presence of exotic invasive species penalizes the overall diversity; thus, even when a doline is the most diverse, it can have a lower evaluation due to the presence of species that harm the ecosystem.

The Hierarchical cluster analysis showed three groups (group average cluster method, Euclidean distance, Fig. 2), with the most representative observation per cluster as follows: 1-Maravilla, 2-Chu-ha, and 3-Helechos; the least representatives were Maravilla, El Arco and Royal 1. This assemblage is given by the sub-indices evaluation and is not spatially based; for instance, Royal 1 and Royal 2 are separated by 500 m and presumably connected; however, they do not form the same group. Thus, we confirm that site characteristics are not confounding variables and the CSI-D targets specifically the environmental condition state.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reported that the cumulative variance in the first two components was 61.54%, being the most important factor in the positive axis metals (M), microplastics (MP), and Zooplankton diversity (Zoo); whereas Fish diversity (Fish), Trophic state (TS) and Fecal virus (Virus) the factors relevant in the negative axis (Fig. 3). Fecal bacteria are not relevant to the analysis given that all dolines received the same evaluation. This is important to emphasize because the indicator that penalized most of the condition state evaluation does not have an influence when analyzing our results with this multivariate analysis; yet, contrary to general interpretation, its relevance is elevated when evaluated with a weighted index.

Discussion

The use of various assessment methods of water quality is optimally complemented in the CSI-D index with two community structure indexes, a recommendation that has been previously expressed, but rarely used for comprehensive water quality assessments43. Each one of the indicators included in the CSI-D is intertwined with the others and can cause unpredicted synergistic effects, thus the need for proper water resources management and strengthening of conservation and protection strategies in dolines in urban areas as in any other aquatic ecosystem. As with many other indices, integrating parameters with different scales, and valuations, and reducing environmental variables into a one-dimension index, in addition to measurement errors and biases, may be considered a major flaw or drawback in the representation of reality73. Nonetheless, assessment models have been used and likely will be used for the time to come, due to their predictive power for water quality status based on data directly obtained from the field. When more than one assessment method is used to explore the environmental condition of ecosystems as with the CSI-D, we have the advantage of evaluating several aspects of water, each one with its assessment expression43. The assessment completed with this index is not definitive and might not represent the actual health condition of the evaluated dolines. As with any other index, periodical evaluation of the condition status with the same metrics is necessary to allow accurate assessment of the environmental health of these karstic features, particularly targeting the status of the aquifer in these sites due to their exposure to the atmosphere and terrestrial ecosystems, including all anthropic impacts23.

When comparing indices, we noticed that an approach including both the environmental conditions (surface or groundwater) and biodiversity is not common when evaluating environmental quality or conditions state (Table 10). The paper by Begum et al.74 which evaluates both water quality and biodiversity, did the evaluation separately and then related the results. The multimetric trophic state index TRIX is a proper evaluation for dolines in urban areas given that it can capture spatial and temporal variability, particularly when it is modified by physical and chemical parameters, derived not only from hydrological and seasonal oscillations but also from anthropogenic factors26. One very important observation for improved use of the CSI-D is to include as many values as we have available for the integration of the TRIX at a seasonal scale, providing information valuable for adapting management strategies, prioritizing resources, and assessing natural vs. man-made restoration.

WQI-Water quality index, GWQI-Groundwater quality index, PVCL- Pathogenic Virus Contamination Level, TDS-Total dissolved solids, TSS-total suspended solids, EC-electrical conductivity, Turb-Turbidity, DO-dissolved oxygen, BOD-Biological oxygen demand, COD-Chemical oxygen demand, Alk-Total alkalinity, Tran-Transparency, AMN-Ammonia nitrogen, DIN-dissolved inorganic nitrogen, TON-Total organic nitrogen, MRP-molybdate reactive phosphorus, TMV-Tobacco mosaic virus, PMMoV- Pepper mild mottle virus, JCPyVs, and BKPyVs-Polyomaviruses.

The fecal sub-indices point to the entrance of water enriched with fecal detritus affecting all sites. Once the fecal indicators were introduced as part of an index, the next challenge was to determine if the source of the fecal contamination was from anthropic origin or otherwise. This needs to be considered cautiously because these sites are not identified as receptors of any intentional or planned wastewater discharge; rather, they are likely non-point sources, namely sewage leaks from surrounding urban infrastructure, leaks from defective septic systems, runoff with fecal material from stray dogs, cats and other mammals from the area, not exclusive of human origin81 and even from the garbage and solid waste from the surrounding areas82. Nonetheless, it is a prominent parameter in a multimetric index, as the integration of parameters with values commonly above the permissible limit or hard to achieve (such as fecal indicators) increases the value of the index, making it simultaneously truthful and astringent.

Viral fecal indicators such as PMMoV are currently proposed as alternatives to fecal indicator bacteria, since they can aid in the evaluation of water quality, due to the great persistence of this virus in comparison to other fecal indicators83,84. In addition, a baseline for the concentration of somatic coliphages, F + specific coliphages, and PMMoV has been conducted the karst aquifer and in wastewater in the same area28,51,85, providing important information for the understanding of the fate of viral fecal indicators in the karst environment. However, very little information is available to date regarding the occurrence of viral pathogens in island aquifers. In this study, we report for the first time the occurrence of viral fecal indicators in groundwater from the third largest and most populated island in Mexico. This is important because fecal viral indicators such as PMMoV have been often associated with the presence of waterborne enteric viruses that can pose a risk to human health27 causing gastrointestinal illnesses worldwide. Given that the Cozumel island aquifer is the only source of freshwater for human consumption, and, according to official data86 Cozumel has the highest gastrointestinal illness rates in the state of Quintana Roo. Thus, it is important to develop tools for the assessment of water that are more complex than traditional indexes based only on water quality, where viruses are not considered.

Almost all metals in soils are more weathered in the upper layer than in deeper layers because of rainfall, temperature variations, and greater biological activity. Cd is mobile and bioavailable under certain environmental conditions and it has been reported that it does not form stable complexes with organic matter due to the low solubility of these compounds87,88. Thus, Cd is most likely found either in the exchangeable fraction or in the residual phase. When present in the exchangeable phase, it is available to the environment and biota because it does not stay in the water for long periods before being translocated into organisms. On the other hand, when is in the residual phase, it is bound to the mineral fraction and not easily mobilized88. That is to say, Cd is not present in water unless there are changes that release it from the exchangeable phase, perhaps recently entered metals into the ecosystem. It is not common to find copper in the exchangeable or soluble phases; therefore, it is not easily released in the water column due to the great stability of organometallic copper compounds88. Previous research in urban or suburban soils has reported Cu in available phases, indicating that anthropogenic activities increase the concentration of this metal89. The values found in this research may indicate that Cu is found in high concentration in the non-mobile phases-lattice structures in soils; yet, does not represent a hazard due to its reduced availability to plants and microorganisms90.

It is difficult to find a pattern for Zn, but in general, it is commonly found in all phases, from soluble to organic matter-bound. Soil characteristics are determinants for the concentration in which Zn is found in each specific phase87. Similar to Cu, Zn is found in greater quantities in urban-type soils, namely from transportation and construction91. Regarding iron, the measured concentration in the exchangeable phase might be the result of soluble organic acids leachate (from soil organic matter) that form aqueous complexes. Fe in soil solution mainly exists as soluble organic complexes rather than inorganic ions, because free ferrous ions (Fe2+) are scarce under aerobic conditions92. Lastly, manganese is common in the soluble and exchangeable phases due to its weak union with organic matter92; it is not a metal of great concern and has been previously reported in these phases in urban soils61 due to its high solubility, that can be easily released into water93. Summarizing, based on the measured concentrations and considering the mobility factors, Cd represents low risk at Arco, whereas Zn represents low to medium risk at all dolines.

In all the evaluated dolines, there is the presence of four important groups of zooplankton. This community is very important because it participates in recycling nutrients, transferring energy, and controlling pathogenic organisms for human health. Its presence, richness, and abundance have been related to the health condition of the site, responding to environmental factors94. It is accepted that maintaining biodiversity ensures environmental health and ecological processes, and the opposite is associated with environmental degradation95. Zooplankton biodiversity is a good indicator of environmental conditions as they respond quickly to changes in health status and climatic variations, giving good results when integrating environmental assessments with other biological, physical, and chemical variables96,97. There is a limited diversity observed in the current evaluation, due to previous reports of as high as 40 species of rotifers in dolines, caves, and natural areas in Cozumel98, in addition to new zooplankton records such as the diaptomid copepod Mastigodiaptomus ha and the anchialine copepod Speleophria germanyanezi n. sp99,100. Our knowledge of potential sentinel species in dolines in urban areas is limited; therefore, it is imperative to continue collecting and identifying zooplankton species of the groups Rotifera, Ostracoda, and Cladocera, because they are sensitive to environmental disturbances101 and can become an additional tool for long-term environmental monitoring. The results of the CSI-D indicate that the most common genera were Lecane and Brachionus, very common organisms of coastal environments. They are relevant to the environment because they intervene in the degradation of organic matter, controlling eutrophication as consumers of primary producers and pathogens, and are valuable in the transfer of energy in food webs99.

Possibly, the most important problems that affect the biodiversity in dolines are increased urbanization, contamination by urban waste and wastewater, and habitat fragmentation21 but can also include construction, filling of wetlands, and introduction of exotic species102. Assessing the health status of an ecosystem with fish biodiversity and site quality is an approach used by fish-based indices of biotic integrity (FIBI); in which the index score varies depending on the presence or absence of indicator species103. The CSI-D weights positive and negative attributes of species richness and dominance by rewarding protected or endemic species and penalizing exotic invasive species. Although it is not a diversity-based index, its addition helps to provide more comprehensive assessments than traditional indexes based only on water quality. Poecilia velifera can be found in dolines, mangroves, and estuaries; it has ample geographical distribution but restricted habitat. Gambusia yucatana is an abundant protected species due to its category of endemic; it lives in coastal environments associated with mangrove areas under highly variable salinity, dissolved oxygen, and temperature conditions67. It has a main diet of algae and vascular plants, but also feeds on insect larvae; thus, is useful for mosquito control. There are two other endemic species previously registered in Cozumel (Cyprinodon artifrons and Floridichthys polyommus103), but were not observed in our sampling campaign. We expect that integrated evaluations such as the CSI-D contribute with evidence to the discussion about the environmental services provided by biodiversity, in favor of the stance that higher biodiversity allows a higher level of ecosystem services and that this information can be obtained also with multimetric indices.

It is important to mention the fish species endemic to the island. The Mexican blind brotula Typhliasina pearsei locally known as “Dama Blanca”, is the only freshwater species of the family of viviparous brotulas, endemically distributed throughout the Yucatan Peninsula; apparently, the existing species on the island still maintains the presence of eyes; thus, it might be a variety of new species. Also, a goby of the Eleotridae family has been identified in some dolines from Cozumel (Yañez-Mendoza, Pers. Comm.).

Conclusion

Water pollution is the quintessential challenge in urban areas and urban areas have significant impacts on all the functions of ecosystems and biodiversity, negatively affecting the water and environmental quality, as well as human and wildlife health. The use, creation, or application of multimetric indices are increasingly complementing the evaluation of aquatic ecosystems by classical water quality assessments using physicochemical data. The condition status index of dolines in urban areas (CSI-D) presents a methodology for assessing the environmental condition of an dolines in urban areas that can be applied anywhere in the world. It is a multimetric index developed and tested a for dolines in an urbanized landscape, which allows to conduct a proper assessment of the condition status of dolines, likely applicable to other karst water bodies that offer a two-way access to the aquifer, such as flooded caves, karst springs, estavelles, sinking streams or ponors elsewhere in the world. Although is it designed with some of the most sensitive parameters for strict evaluation of aquatic karst landscapes, it can be adapted when specific indicators (such as fecal virus) are not possible to include. Recurrent evaluation of the condition status with this index (i.e., as being part of a monitoring), will likely assist in evincing sources. The increase in average temperatures, altered precipitation, and sea level rise can have irreversible effects on the urban water cycle; thus, there can be a change in the infiltration and groundwater recharge process, which can alter habitats, affect the migration and reproduction of species, and contribute to enhanced groundwater contamination.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Hiscock, K. M. Hydrogeology: Principles and Practice (Blackwell Publishing, 2005).

Fischer, P., Pistre, S. & Marchand, P. Effect of fast drainage in karst sinkholes on surface runoff in Larzac Plateau, France. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 43, 101206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2022.101206 (2022).

Van Beynen, P. Karst Management (Springer, 2011).

Stevanović, Z. Global distribution and use of water from karst aquifers. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 466(1), 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP466.17 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. The World Karst Aquifer Mapping project: Concept, mapping procedure and map of Europe. Hydrogeol. J. 25, 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-016-1519-3 (2017).

Ford, D. C. & Williams, P. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology (Wiley, 2007).

Polk, J. S. & Brinkmann, R. Climatic Influences on coastal cave and karst development in Florida. In Coastal Karst Landforms Coastal Research Library Vol. 5 (eds Lace, M. & Mylroie, J.) (Springer, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5016-6_15.

Parise, M. Sinkholes. In Encyclopedia of Caves 3rd edn. (Academic Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814124-3.00110-2

Van Beynen, P. & Townsend, K. A. Disturbance index for karst environments. Environ. Manag. 36, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0265-9 (2005).

Gutierrez, F., Parise, M., DeWaele, J. & Jourde, H. A review on natural and human induced geohazards and impacts in karst. Earth-Sci. Rev. 138, 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.08.002 (2014).

Zhou, W. & Beck, B. F. Management and mitigation of sinkholes on karst lands: An overview of practical applications. Environ. Geol. 55, 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-1035-9 (2008).

Lindsey, B. D. et al. Relations between sinkhole density and anthropogenic contaminants in selected carbonate aquifers in the eastern United States. Environ. Earth Sci. 60, 1073–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-009-0252-9 (2010).

Seto, K., Parnell, S. & Elmqvist, T. A global outlook on urbanization. In Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities: A Global Assessment (eds Elmqvist et al.) (Springer, 2013).

Qi, S., Guo, J., Jia, R. & Sheng, W. Land use change induced ecological risk in the urbanized karst region of North China: A case study of Jinan city. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-020-09036-w (2020).

De la Rosa, D. et al. A land evaluation decision support system (MicroLEIS DSS) for agricultural soil protection with special reference to the Mediterranean region. Environ. Model. Softw. 19(10), 929–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2003.10.006 (2004).

Corwin, D. L., Hopmans, J. & De Rooij, G. H. From field- to landscape-scale vadose zone process: Scales issues, modeling, and monitoring. Vadose Zone J. 5(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2006.0004 (2006).

Parise, M. & Gunn, J. Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas: Recognition, analysis and mitigation. In Geological Society, vol 279. (Special Publications, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1144/SP279.1

Day, M. J. Natural and anthropogenic hazards in the karst of Jamaica. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec.l Publ. 279, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP279.14 (2007).

Aguilera, H. & Murillo, J. M. The effect of possible climate change on natural groundwater recharge based on a simple model: A study of four karstic aquifers in SE Spain. Environ. Geol. 57, 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1381-2 (2009).

Gutiérrez, F., Parise, M., De Waele, J. & Jourde, H. A review on natural and human-induced geohazards and impacts in karst. Earth-Sci. Rev. 138, 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.08.002 (2014).

Kollaus, K. A., Behen, K. P. K., Heard, T. C., Hardy, T. B. & Bonner, T. H. Influence of urbanization on a karst terrain stream and fish community. Urban Ecosyst. 18, 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-014-0384-x (2015).

Mazzei, M. & Parise, M. On the implementation of environmental indices in karst. In Karst groundwater contamination and public health. Advances in Karst Science (eds White, W. et al.) (Springer, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51070-5_28.

Van Beynen, P. & Townsend, K. A disturbance index for karst environments. Environ. Manag. 36, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0265-9 (2005).

Blenckner, T. et al. The Baltic health index (BHI): Assessing the social–Ecological status of the Baltic Sea. People Nat. 3(2), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10178 (2021).

UN. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2023). https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/about-un-decade

Brugnoli, E. et al. Assessing multimetric trophic state variability during an ENSO event in a large estuary (Río de la Plata, South America). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 28, 100565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100565 (2019).

Kitajima, M., Sassi, H. P. & Torrey, J. R. Pepper mild mottle virus as a water quality indicator. npj Clean Water https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-018-0019-5 (2018).

Rosiles-González, G. et al. Occurrence of pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) in groundwater from a karst aquifer system in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Food Environ. Virol. 9, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12560-017-9309-1 (2017).

Canh, V. D., Lien, N. T. & Nga, T. T. V. Evaluation of the suitability of pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) as an indicator virus for water safety and quality. J. Sci Technol. Civil Eng. (STCE) - HUCE 16(2), 76–88 (2022).

Chapman, P. M. Determining when contamination is pollution—Weight of evidence determinations for sediments and effluents. Environ. Int. 33(4), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2006.09.001 (2007).

Briffa, J., Sinagra, E. & Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04691 (2020).

Nanda, S. & Berruti, F. Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 1433–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01100-y (2021).

Karbalaei, S., Hanachi, P., Walker, T. R. & Cole, M. Occurrence, sources, human health impacts and mitigation of microplastic pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 36046–36063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3508-7 (2018).

Arriaga, L. Aguas continentales y diversidad biológica de México. CONABIO (2000).

Hillebrand, H., Cowles, J. M., Lewandowska, A., Van de Waal, D. B. & Plum, C. Think ratio! A stoichiometric view on biodiversity–ecosystem functioning research. Basic Appl. Ecol. 15(6), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2014.06.003 (2014).

Torres-Estrada, J. L. & Vázquez-Martínez, M. G. Copepods (Crustacea: Copepoda) as agents of biological control of Aedes mosquito larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Chiapas, Mexico. Hidrobiológica 25(1), 1–6 (2015).

Gannon, J. E. & Stemberger, R. S. Zooplankton (especially crustaceans and rotifers) as indicators of water quality. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 97(1), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/3225681 (1978).

Trishala, K. P., Rawtani, D. & Agrawal, Y. K. Bioindicators: the natural indicator of environmental pollution. Front. Life Sci. 9(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/21553769.2016.1162753 (2016).

Declerck, S. A. J. & De Senerpont Domis, L. N. Contribution of freshwater meta zooplankton to aquatic ecosystems services: an overview. Hydrobiologia 850, 3795–2810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-022-05001-9 (2022).

Mcdowall, R. M. & Taylor, M. J. Environmental indicators of habitat quality in a migratory freshwater fish fauna. Environ. Manag. 25(4), 357–374 (2000).

Oberdorff, T., Pont, D., Hugueny, B. & Porcher, J. P. Development and validation of a fish-based index for the assessment of river health in France. Freshw. Biol. 47(9), 1720–1734. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00884.x (2002).

Abbasi, T. & Abbasi, S. A. Water Quality Indices (Elsevier, 2012).

Yan, T., Shen, S. L. & Zhou, A. Indices and models of surface water quality assessment: Review and perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 308, 119611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119611 (2022).

Vollenweider, R. A., Giovanardi, F., Montanari, G. & Rinaldi, A. Characterization of the trophic conditions of marine coastal waters with special reference to the NW Adriatic Sea: Proposal for a trophic scale, turbidity and generalized water quality index. Environmetrics 9(3), 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-095X(199805/06)9:3%3c329::AID-ENV308%3e3.0.CO;2-9 (1998).

Lorenzen, C. J. Determination of chlorophyll and pheo-pigments: Spectrophotometric equations 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 12(2), 343–346 (1967).

OECD. Eutrophication of waters. Monitoring, assessment, and control. OECD Cooperative Programme on monitoring inland waters (Eutrophication control), Environment Directorate. OECD, Paris (1982).

SEMARNAT. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021. Que establece los límites permisibles de contaminantes en las descargas residuales en cuerpos receptores propiedad de la Nación.Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México, 11 de marzo de 2022 (2022).

USEPA. Review of coliphages as possible indicators of fecal contamination for ambient water quality. EPA 820-R-15-098 Office of Water, Science and Technology Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Washington, DC (2015).

Katayama, H., Shimasaki, A. & Ohgaki, S. Development of a virus concentration method and its application to detection of enterovirus and Norwalk virus from coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68(3), 1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.3.1033-1039.2002 (2002).

Zhang, T. et al. RNA viral community in human feces: Prevalence of plant pathogenic viruses. PLoS Biol. 4(1), e3. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040003 (2006).

Muñoz-Cortés, C. E. et al. Occurrence of enteric viruses and fecal indicators in submarine groundwater discharges in the coastal environment of the Mexican Caribbean. Water Environ. J. 37(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/wej.12815 (2022).

da Costa, J. P., Avellan, A., Mouneyrac, C., Duarte, A. & Rocha-Santos, T. Plastic additives and microplastics as emerging contaminants: Mechanisms and analytical assessment. Trends Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116898 (2022).

Walker, T. R. (Micro) plastics and the UN sustainable development goals. Current Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 30, 100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100497 (2021).

Masura, J. Baker, J. Foster, G. & Courtney, A. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: recommendations for quantifying synthetic particles in waters and sediments, NOS-OR&R-4, NOAA Tech. Memo 39 (2015).

Migwi, F. K., Ogunah, J. A. & Kiratu, J. M. Occurrence and spatial distribution of microplastics in the surface waters of Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 39, 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4677 (2020).

Prata, J. C. Microplastics in wastewater: State of the knowledge on sources, fate and solutions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 129(1), 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.02.046 (2018).

Mendoza-Olea, I. J. et al. Contaminación por microplásticos en el acuífero kárstico de la península de Yucatán. Ecosistemas Y Recursos Agropecuarios https://doi.org/10.19136/era.a9n3.3360 (2022).

Godoy, V., Martín-Lara, M. A., Almendros, A. I., Quesada, L., & Calero, M. Microplastic pollution in water. In Water Pollution and Remediation: Organic Pollutants (Springer, 2021).

Lusher, A. L., Welden, N. A., Sobral, P. & Cole, M. Sampling, isolating and identifying microplastics ingested by fish and invertebrates. In Analysis of Nanoplastics and Microplastics in Food. (CRC Press, 2017).

Boyd, C. E. Water Quality (Springer, 2020).

Ortega-Camacho, D., Acosta-González, G., Sánchez-Trujillo, F. & Cejudo, E. Heavy metals in the sediments of urban sinkholes in Cancun, Quintana Roo. Sci. Rep. 13, 7031. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34218-4 (2023).

Tessier, A., Campbell, P. G. & Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal. Chem. 51(7), 844–851. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac50043a017 (1979).

SEDUE. Criterios ecológicos de calidad del agua CE-CCA-001/89. Diario Oficial de la Federación (1989).

Koste, W. Rotatoria. Die Radertiere Mitteleuropas (Borjtraeger, 1978).

Segers H. World records of Lecanidae (Rotifera, Monogononta). Editiom de Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique (1995).

SEMARNAT. Norma Oficial Mexicana Secretaría de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo (2010). https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4254/semarnat/semarnat.htm

Schmitter-Soto, J. J. Catálogo de los peces continentales de Quintana Roo. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico (1998).

Robertson, D. R., Peña, E. A., Posada, J. M., & Claro, R. Peces costeros del Gran Caribe: Sistema de información en línea. Version 2.0. Instituto Smithsonian Investigación Tropical, Balboa, Panamá (2019). https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean.

OriginPro. OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA (2021).

INEGI. Aspectos Geográficos Quintana Roo 2021, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México (2022).

INEGI. Compendio de información geográfi¬ca municipal 2010 Cozumel Quintana Roo. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México (2010).

INEGI. 'AGEE Área Geoestadística Estatal’, escala: 1:250000. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. México, Ciudad de México (2024). Online access: http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/dest23gw.html

Brown, E. D. & Williams, B. K. Ecological integrity assessment as a metric of biodiversity: Are we measuring what we say we are?. Biodivers. Conserv. 25, 1011–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1111-0 (2016).

Begum, W., Goswami, L., Sharma, B. B. & Kushwaha, A. Assessment of urban river pollution using the water quality index and macro-invertebrate community index. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 8877–8902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02369-5 (2023).

Sánchez, J. A., Álvarez, T., Pacheco, J. G., Carrillo, L. & González, R. A. Calidad del agua subterránea: Acuífero sur de Quintana Roo, México. Tecnología y ciencias del agua 7(4), 75–96 (2016).

Silva, J. T. et al. Calidad química del agua subterránea y superficial en la cuenca del río Duero, Michoacán. Tecnología y ciencias del agua 4(5), 127–141 (2013).

Ghosh, A. & Bera, B. Hydrogeochemical assessment of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation applying groundwater quality index (GWQI) and irrigation water quality index (IWQI). Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 22, 100958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2023.100958 (2023).

Adimalla, N. & Qian, H. Groundwater quality evaluation using water quality index (WQI) for drinking purposes and human health risk (HHR) assessment in an agricultural region of Nanganur, south India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 176, 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.03.066 (2019).

Harun, H. H. et al. Association of physicochemical characteristics, aggregate indices, major ions, and trace elements in developing groundwater quality index (GWQI) in agricultural area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(9), 4562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094562 (2021).

Uddin, M. G., Nash, S., Rahman, A. & Olbert, A. I. A comprehensive method for improvement of water quality index (WQI) models for coastal water quality assessment. Water Res. 219, 118532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.118532 (2022).

McCurry, S. W., Coyne, M. S. & Perfect, E. Fecal coliforms transport through intact soil blocks amended with poultry manure. J. Environ. Quality 27(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq1998.00472425002700010013x (1998).

Leal-Bautista, R. M., Lenczewski, M., Morgan, C., Gahala, A. & McLain, J. E. Assessing fecal contamination in groundwater from the tulum Region, Quintana Roo, Mexico. J. Environ. Prot. 4(11), 1272–1279. https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2013.411148 (2013).

Rzeżutka, A. & Cook, N. Survival of human enteric viruses in the environment and food. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28(4), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2004.02.001 (2004).

Greaves, J., Stone, D., Wu, Z. & Bibby, K. Persistence of emerging viral fecal indicators in large-scale freshwater mesocosms. Water Res. X 9, 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wroa.2020.100067 (2020).

Rosiles-González, G. et al. Environmental surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and groundwater in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Food Environ. Virol. 13, 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12560-021-09492-y (2021).

Boletín epidemiológico del Estado de Quintana Roo. (2022). Servicios Estatales de Salud. Epidemiología. Información para la acción. Gobierno del Estado de Quintana Roo. Available at https://qroo.gob.mx/sites/default/files/unisitio2023/06/BoletinEstatalSem20.pdf

Sposito, G., Lund, L. J. & Chang, A. C. Trace metal chemistry in arid-zone field soils amended with sewage sludge: I. Fractionation of Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd, and Pb in solid phases. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 46(2), 260–64. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1982.03615995004600020009x (1982).

Mahanta, M. & Bhattacharyya, K. G. Total concentrations, fractionation and mobility of heavy metals in soils of Urban Area of Guwahati, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 173, 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-010-1383-x (2011).

da Silva, E. B. et al. Background concentrations of trace metals As, Ba, Cd Co, Cu, Ni, Pb, Se, and Zn in 214 Florida Urban soils: Different cities and land uses. Environ. Pollut. 264, 114737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114737 (2020).

Asmoay, A. S. A., Salman, S. A., El-Gohary, A. M. & Sabet, H. S. Evaluation of heavy metal mobility in contaminated soils between Abu Qurqas and Dyer Mawas Area, El Minya Governorate, Upper Egypt. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre 43, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0133-7 (2019).

Long, Z. et al. Contamination, sources and health risk of heavy metals in soil and dust from different functional areas in an industrial City of Panzhihua City, Southwest China. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126638 (2021).

Walna, B., Spychalski, W. & Ibragimow, A. Fractionation of iron and manganese in the horizons of a nutrient-poor forest soil profile using the sequential extraction method. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 19(5), 1029–1037 (2010).

Osakwe, S. A. Chemical speciation and mobility of some heavy metals in soils around automobile waste dumpsites in Northern part of Niger delta, South Central Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v14i4.63284 (2011).

Barinova, S. S. Empirical model of the functioning of aquatic ecosystems. Int. J. Oceanogr. Aquac. 1(3), 000113 (2017).

Sandifer, P. A., Sutton-Grier, A. E. & Ward, B. P. Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: Opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation. Ecosyst. Serv. 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.007 (2014).

Cervantes-Martínez, A. & Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M. A. Physicochemistry and zooplankton of two karstic sinkholes in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. J. Limnol. 74(2), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.4081/jlimnol.2014.976 (2015).

Flesch, F., Berger, P., Robles-Vargas, D., Santos-Medrano, G. E. & Rico-Martínez, R. Characterization and determination of the toxicological risk of biochar using invertebrate toxicity test in the state of Aguascalientes, México. Appl. Sci. 9(8), 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9081706 (2019).

Arroyo-Castro, J. L., Alvarado-Flores, J., Uh-Moo, J. C. & Koh-Pasos, C. G. Monogonot rotifers species of the island Cozumel, Quintana Roo, México. Biodivers. Data J. 7, e34719. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e34719 (2019).

Cervantes-Martínez, A., Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M. A., Suárez-Morales, E. & Jaime, S. Phenetic and genetic variability of continental and island population of the freshwater copepod Mastigodiaptomus ha Cervantes, 2020 (Copepoda): A case of dispersal?. Diversity 13(6), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13060279 (2021).

Suárez-Morales, E., Cervantes-Martínez, A., Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M. A. & Iliffe, T. M. A new Speleophria (Copepoda, Misophrioida) from an anchialine cave of the Yucatán Peninsula with comments on the biogeography of the genus. Bull. Mar. Sci. 93(3), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2017.1012 (2017).

Pinto, I., Nogueira, S., Rodrigues, S., Formigo, N. & Antunes, S. C. Can zooplankton add value to monitoring water quality? A case study of a meso/eutrophic Portuguese reservoir. Water 15, 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15091678 (2023).

Bezerra, L. A. V. et al. A network meta-analysis of threats to South American fish biodiversity. Fish Fish. 20(4), 620–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12365 (2019).

Grinstead, S., Kelly, B., Siepker, M. & Weber, M. J. Evaluation of two fish-based indices of biotic integrity for assessing coldwater stream health and habitat condition in Iowa’s Driftless Area, USA. Aquat. Ecol. 56(4), 983–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-022-09958-6 (2022).

Acknowledgements

To the staff of Cozumel municipality Seidy Crespo, Jacquelinne Flores, Lemuel Mena, Gibrán Tuxpan, and Germán Yáñez. Thanks to the Cozumel City Council (Ayuntamiento de Cozumel) in the 2021-2024 administration. Claudia Ávalos Echeagaray and Itzel Jocelin Mendoza-Olea assisted in laboratory analyses. This work was supported by CONAHCYT (Grant numbers Catedras CONAHCYT 2944) and partial financial support was received from Ayuntamiento de Cozumel, Quintana Roo. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: EC, GAG Data curation: GAG, JAF, JCCP, JEBG, DOC, GRC Formal analysis: EC, GAG, JEF, JCPP, JEBG, DOC, GRG Investigation: EC, JAF, JCPP, RMLB Methodology: EC, GAG, JAF, JCPP, JEBG, RMLB, DOC, GRG, JACV, CHZ Project administration: EC, GAG, JAF, RMLB, JACV, CHZ Resources: EC, GAG, JAF, JCPP, JEBG, RMLB, DOC, GRG, JACV, CHZ Supervision: EC Visualization: GAG Writing-original draft: EC Writing-review & editing: EC, GAG, JAF, JCPP, JEBG, RMLB, DOC, GRG, JACV, CHZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cejudo, E., Acosta-González, G., Alvarado-Flores, J. et al. The condition status index for doline lakes in urban areas. Sci Rep 14, 26815 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75444-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75444-8