Abstract

Food motivation varies between individuals, affecting body weight and risk for eating disorders. Prior neuroimaging studies in youth and adults have revealed functional and structural alterations in the anterior cingulate cortex [ACC] in those with obesity and disordered eating but have not investigated their neurochemical underpinnings. In a sample of 37 children aged 4 to 13 years old, we used Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy [MRS] to assess levels of γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA] – the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the human brain – quantified relative to creatine in a 27-ml voxel including the dorsal ACC. We used the CEBQ to assess trait food motivation. In analyses adjusting for age, lower GABA+/Cr levels in the dorsal ACC were associated with higher trait enjoyment of food. Higher enjoyment of food scores were in turn associated with higher energy intake during an ad libitum test meal and during a postprandial task assessing intake in the absence of hunger, and higher body weight. Our results indicate a role for GABA function in the dorsal ACC in determining individual variation in food motivation in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food motivation varies between individuals both in adulthood1 and childhood. Understanding the biological basis for this variation has significant clinical and health relevance. High levels of food motivation may increase the risk of developing excess body weight2 or disordered eating behaviors, such as binge eating3. Conversely, low levels of food motivation may increase the risks of low weight, malnutrition, pediatric feeding disorders or low weight eating disorders2,4,5,6,7.

A critical neural substrate for motivated behavior based on balancing reward value with competing attributes is the anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]8,9,10,11,12. In particular, the dorsal ACC [dACC], which projects to the prefrontal cortex13,14 as well as the basal ganglia15, is implicated in cognitive control and executive functions16,17,18,19, including reward-based decision making20. Recent integrative theories suggest that different regions within the ACC may work together to learn to predict the outcomes of actions, generating error signals when predictions and actual outcomes are compared, thus helping to guide action selection21. Consistent with the role of the ACC in motivated behavior, prior neuroimaging studies have shown functional and structural alterations of the ACC in relation to obesity and disordered eating22,23,24,25,26. Familial obesity risk and current overweight in adolescents is associated with decreased activation of the dACC to food cues22 as well as with decreased ACC volume27,28, and higher child BMI has been associated with decreased ACC responses to food cues following glucose ingestion29. Conversely, patients with anorexia nervosa show increased activation of the ACC to visual food cues30,31. Adolescents with obesity additionally show decreased cortical thickness in ACC32 and decreased connectivity between dACC and insula33 compared to healthy-weight adolescents. Further, uncontrolled eating characterized by maladaptive decision-making in relation to food, is associated with decreased ACC volume34, while children with increased emotional eating show decreased ACC responses to food cues35.

Although extant neuroimaging evidence for altered ACC structure and function in obesity and eating disorders is compelling, it is unable to address the neurochemical underpinnings of such differences. Gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA] is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and can be assessed by edited Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy [MRS]. MRS is able to estimate the concentration of specific metabolites (e.g. GABA) within a localized volume of tissue by identifying the resonance frequency of that molecule. It primarily, although not exclusively, measures the intracellular concentration of the metabolite within the voxel. In vivo measurement of GABA via conventional MRS is challenging due to overlapping signals from creatine-containing compounds36,37, but can be addressed using Hadamard Encoding and Reconstruction of MEGA-Edited Spectroscopy [HERMES]38, a novel J-difference editing method that selectively detects multiple metabolites simultaneously and removes overlapping signals, providing an opportunity to simultaneously assess glutathione [GSH] – an antioxidant with no hypothesized relationship to motivated behavior – as a control.

GABA levels in the dACC are elevated during learning under conditions of uncertainty (potentially reflecting recruitment of inhibitory systems during high cognitive load), with higher baseline GABA levels associated with improved learning39. dACC GABA is also positively associated with resting state connectivity in the central executive network and negatively associated with functional coupling of the default mode network and central executive network, suggesting a role in regulating shifts between distinct cognitive processes40. Further, lower GABA levels in ACC/dACC have been associated with greater impulsivity41,42 and decreased harm avoidance43, and lower dACC GABA has been associated with greater discounting of low-value rewards44. Decreased ACC GABA has also been reported in several clinical contexts including panic disorder45, sleep disturbances46,47, and major depressive disorder48,49,50, as well as in association with impaired cognitive function (e.g. attentional bias, impulsivity) in smokers51,52. Higher BMI has been associated with lower levels of N-acetyl-aspartate (a marker of neuronal integrity) relative to creatine in the ACC as assessed by MRS in a healthy middle-aged cohort53, but to our knowledge the role of the ACC GABAergic system in appetite has yet to be examined.

To examine the role of GABA in the dACC in food motivation, we used MRS to assess GABA levels, relative to creatine (GABA+/Cr), in a 27-ml voxel including the dACC, and the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) to assess trait food motivation, in a sample of 37 children aged 4 to 13 years old. Based on the evidence reviewed above indicating an inhibitory role of the dACC in food motivation and ACC GABA in optimizing value-based decision making, our primary hypothesis was that higher dACC GABA+/Cr levels would be negatively associated with trait food motivation in children but not with dACC levels of GSH/Cr, an indicator of neural oxidative stress which we did not hypothesize to be associated with food motivation. Finally, as an internal validation of the trait food motivation measure, we tested the relationship of trait food motivation with energy intake in an ad libitum test meal and eating in the absence of hunger test as a secondary aim, hypothesizing positive associations.

Results

Sample characteristics

Thirty-seven children (17 Male, 20 Female) with a mean age of 9.69 years old (SD = 3.04; Range = 4.03–13.89) underwent an MRS scan. MRS data from 32 children were usable, spectra shown in Fig. 1. Five GABA-edited and GSH-edited spectra were removed from further analysis due to the data quality not reaching threshold. The CEBQ was completed by all 37 parents. Thirty five children completed both the ad libitum meal [ALM] and Eating in the Absence of Hunger [EAH] test. Full sample means, standard deviations [SD], and ranges for the Enjoyment of Food subscale and kcals consumed during the ALM and EAH test are shown in Table 1. Based on US reference data54, the mean BMI z-score was 0.57 (SD = 1.17; Range = −.39 to 2.80) and mean BMI percentile was 64.95 (SD = 28.73; Range = 1–100). There were 10 children with obesity and 0 children in the overweight category. Based on parental report, one participant was categorized as Black or African American, 21 as White, four as more than one race, and one as other. In terms of ethnicity, three participants were categorized as Hispanic or Latino, 33 as not Hispanic or Latino, and one as other.

Edited difference spectra using Gannet software. (A) Summary of GABA+-edited data. (B) Summary of GSH-edited data. The solid lines represent the group mean, and shaded area represents the range of mean ± one standard deviation (SD). ppm: parts per million. (C) Location of the dACC voxels. Note, each participant’s native space binary voxel mask was normalized to MNI space and overlaid onto the spm152 template. Warmer colors represent area of greater overlap across participants.

GABA+/Cr levels were not significantly associated with BMI z-score (r = −0.265; p = 0.143), BMI percentile (r = −0.212; p = 0.245), or age (r = 0.264; p = 0.144) and did not differ by child weight group (F = 1.864; p = 0.182) or sex (t(30) = 1.336; p = 0.192). CEBQ Enjoyment of Food was positively correlated with age (r = 0.452; p = 0.005) but did not differ by sex (males: mean = 3.19 ± SD 1.15, females: mean = 3.40 ± SD 1.12; p = 0.576).

Associations of GABA+/Cr and GSH/Cr levels with enjoyment of food scores

Lower GABA+/Cr levels were associated with higher CEBQ Enjoyment of Food scores (see Fig. 2) when controlling for age (β = −0.358; R2 = 0.324; p = 0.031). These findings remained statistically significant when additionally controlling for sex (β = −0.352; R2 = 0.324; p = 0.043).

GSH/Cr levels were not associated with CEBQ Enjoyment of Food (see Supplementary Fig. 1) in analyses controlling for age (β = −0.132; R2 = 0.221; p = 0.465) or when additionally controlling for sex (β = −0.144; R2 = 0.235; p = 0.433).

Associations of CEBQ enjoyment of food scores with intake in meal tasks and BMIz score

Correlations of CEBQ Enjoyment of Food with intake in meal tasks and with BMI z-score are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Greater Enjoyment of Food scores were associated with greater calories consumed during the ad libitum meal [ALM] (β = 0.351; p = 0.039) and eating in the absence of hunger [EAH] test (β = 0.341; p = 0.045) (see Fig. 3a + b). These associations were decreased when adjusting for age (β = 0.237; p = 0.149 and β = 0.232; p = 0.154, respectively). Greater Enjoyment of Food scores were additionally associated with greater BMIz score (r = 0.544; p < 0.001; see Fig. 3c).

Neither GABA+/Cr nor GSH/Cr were associated with ALM or EAH intake (see Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that GABA+/Cr levels in the dACC as assessed by MRS, were negatively associated with trait food motivation in a pediatric sample, and this association was maintained when controlling for both age and sex. Notably dACC GSH/Cr was unassociated with either measure of appetite. As far as we are aware, this is the first report of an association of GABA levels with appetitive behavior. Our findings add to existing evidence for a role of the dACC in food motivation22,23,24,25,26,27,28,32,33 and reward-based decision-making20,55,56, as well as specific evidence for a role for dACC GABA in decision-making41,42,44 and interaction within brain networks subserving executive function40.

Lower GABA levels in the dACC could reflect a lesser contribution of the dACC to inhibitory control based on reward value, which manifests in greater food motivation on a measure which is known to be cross-sectionally and prospectively associated with higher body weight in children2. This is consistent with previous findings that lower ACC GABA is associated with greater impulsivity and attentional bias toward smoking-associated words in smokers51,52. Alternatively, dACC GABA may influence functioning of reward circuits such that higher GABA levels decrease reward, thereby reducing trait enjoyment of food. Distinguishing between these hypotheses would require more nuanced measures of food motivation, and large samples with sufficient phenotypic variance to allow differentiation between reward vs. inhibitory control components of appetite regulation. Since altered GABA in the ACC is associated with many psychiatric disorders45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,57,58, further investigation of behavioral relationships using advanced methodologies such as HERCULES59 to provide comprehensive characterization of multiple neurotransmitters and antioxidants in the brain is warranted.

In terms of our secondary aim and hypothesis, we note that trait enjoyment of food was associated with increased energy intake at the ALM and EAH test, as well as with higher BMIz score. These findings are in agreement with a wealth of previous literature describing a positive relationship between CEBQ enjoyment of food scores and body weight60,61. The reduction of this relationship when controlling for age indicates that differences in metabolic needs may contribute to the result but notably age does not confound the observed association of dACC GABA+/Cr levels with trait food motivation since this association withstood control for variation in age. We note that we did not see a significant relationship between GABA+/Cr levels and BMIz score in the current sample, and would likely need a bigger sample with increased BMIz variation to detect such a relationship. We further note that in our exploratory analyses we did not observe significant relationships between GABA+/Cr levels and meal test outcomes in the current study, possibly because CEBQ enjoyment of food scores were more reflective of habitual eating behavior than meal intake assessed at one occasion. Since none of the participants consumed all of the food presented at the ALM or EAH test we do not think that the absence of relationships with food intake variables was due to a ceiling effect created by the amount of the food offered.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size which constrains the generalizability of the findings. The findings presented here are preliminary and require replication in other, larger samples. A further limitation is that the CEBQ is a parent-report measure which is vulnerable to bias. However, the CEBQ has been validated against behavioral tests of eating behavior52, has demonstrated predicted associations with weight across multiple samples in multiple populations2,62, and demonstrated predicted associations with objectively measured eating behavior as well as weight in the current study. The MRS analysis protocol itself has limitations as previously described63, including that the GABA + signal partly reflects contributions from other macromolecules (e.g. homocarnosine). Quantification of GABA + relative to Cr carries the potential for Cr-driven effects, that is only somewhat addressed by use of GSH as a control metabolite. The voxel placement included regions other than the dACC as individual brain size and anatomy is variable. We are unable to conclusively distinguish whether the correlations we observed with our measure of GABA are driven by presynaptic GABA, reflecting its function as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, or extracellular GABA, reflecting a more tonic, neuromodulatory role in cortical inhibition64. Moreover, brain size varies with age. Literature shows that brain volume increases significantly during maturation, particularly within the first two years of life65. Although our analyses controlled for age, gray matter volume fraction was uncorrelated with GABA/Cr levels, and exploration of ACC voxel volumes as transformed into standard space did not suggest any evidence for variation by age (data not shown), it is possible that age-related changes in brain composition associated with changes in brain size are influencing our findings. Future research using longitudinal designs could help to shed light on potential contributions of global and region-specific GABA levels to appetite and weight trajectories in childhood.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that GABA in the dACC may play a role in food motivation, further building upon the association between the dACC and eating behaviors described in previous literature.

Methods

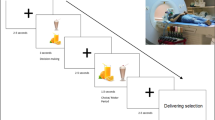

Parents and their children (4–13 years old) in the Baltimore community were invited to participate in a larger research study on obesity risk. This program of work was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB Approval Number: NA_00092328). Healthy English-speaking children who were able to participate in an MRS scan (e.g. no medical contraindication or claustrophobia) were included in the current study. All parents and children older than 8 years old provided written informed consent and assent, respectively. Parents and children completed a battery of questionnaires. In this current study, the questionnaires of interest were general demographic questions and the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire [CEBQ]62,66 to assess children’s appetitive traits. The Enjoyment of Food subscale was selected for this paper as a measure of trait food motivation. After height and weight measurements, children underwent MRS to assess GABA and GSH levels in the dACC. Afterwards, children completed an ALM and EAH test.

MRS acquisition and processing

All data were collected on a Philips 3T Ingenia Elition RX scanner (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, Netherlands) equipped with a 32-channel receive-only head coil. The scanning protocol included a 1 mm3 isotropic T1-weighted MPRAGE for voxel placement and segmentation. The MRS voxel (30(AP) × 30(CC) × 30(RL) mm3) was positioned to capture the anterior cingulate cortex on the frontal lobe midline above the corpus callosum genu, as shown in Fig. 1. The HERMES sequence was used at 3.0 ppm to measure GABA with macromolecules and homocarnosine (GABA+)37 as well as GSH at 2.95ppm. As described previously63, the HERMES sequence used 4 sub-experiments to measure GABA and GSH separately. MR spectra were acquired using following parameters: TE/TR = 80/2000 ms, 304 transients, 2048 data points, 20-ms editing pulse duration, and a 2 kHz spectral width.

MRS data were analyzed using Gannet software (Version 3.1), as previously described63,67. In brief, a 3.0 ppm Creatine [Cr] signal was generated from OFFGABA and OFFGABA/GSH. GABA + and GSH were divided by Cr to create the GABA+/Cr and GSH/Cr integral ratio after frequency-and-phase correction. GABA+/Cr and GSH/Cr integral ratios were uncorrelated with gray matter volume fraction (see Supplementary Fig. 2a + b); therefore, unadjusted values for each participant were used as the primary measures of GABA and GSH in the current paper. Data quality was assessed with water signal linewidth and B0 drift. The threshold for data rejection was two standard deviations above the mean of fit errors.

Child eating behavior questionnaire [CEBQ]

The CEBQ is a parent-report questionnaire used to assess children’s appetitive characteristics66, containing 8 sub-scales comprising 35 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Never to Always. For the current paper we focused on trait food motivation as assessed by the Enjoyment of Food (e.g. “My child enjoys eating”) subscale. The CEBQ is a widely used questionnaire with robust cross-sectional and prospective associations with body weight2 and has previously been validated against behavioral tests of children’s food intake62. We chose to use Enjoyment of Food rather than Food Responsiveness or a combined measure of food approach because we were interested in potential associations of dACC GABA with pathologically low as well as high food motivation, and extant studies are consistent with a stronger relationship of Enjoyment of Food than Food Responsiveness to conditions characterized by food avoidance including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and picky eating6,7,68.

Ad Libitum Meal [ALM]

After the scan, participants were brought to a room with a large buffet of foods including: baby carrots, Kraft Classic Ranch dressing, green grapes, Breyer’s Homemade Vanilla Ice Cream, Ruffles FritoLay potato chips, Cheetos FritoLay, Chips Ahoy cookies, Entenmann’s Little Bites Brownies, M&Ms Classic, and bottled water. For children 4–7 years old the following items were additionally provided: a peanut butter & jelly sandwich; a cheese sandwich; a ham sandwich; extra bread, peanut butter, jelly, cheese and ham; cucumber slices; apple slices; plain and chocolate whole milk, and orange juice. For children 8–14 years old, one cheese pizza, one vegetable pizza, one pepperoni pizza, Sabra hummus, celery sticks, cherry tomatoes, Coke and diet Coke were additionally provided. Amounts of each food were selected to be a visually large amount of food far in excess of 30% of energy requirements for that age group (U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of. Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Edition), i.e. total meal calories offered for 4-7y were approx. 6,832 kcal while total meal calories offered for 8-14y were approx. 14,875 kcal (for full details see Supplementary Tables 3 and for photograph of meal set-up see Supplementary Fig. 3). Participants were asked to “treat the meal like your lunch” and “not to eat for 4 hours following the buffet meal” to encourage ad libitum eating. They were advised that they would be left for 30 min to eat as much of the meal as they would like but could inform the research assistants if they finished early. Children 4–7 yo had one parent present in the room, while children 8–14 yo were alone. Food was weighed pre and post meal to calculate calorie intake.

Eating in the absence of hunger [EAH] test

Following the ALM, participants were brought to a room and instructed “We have one more task for you to complete. I am going to ask you to wait in here while we set up and prepare for the next task. There is an iPad here if you want to play games [or use the Internet- for 8–14 yo participants]. Feel free to eat any of the snacks here, they were left over but not used from another study.” Following the protocols of previous published studies62,69, children 4–7 yo were given 10 min, while children 8–14 yo were given 15 min70. Participants were presented with pre-weighed food. All children were provided with large amounts of Donut Holes, Nabisco Mini Oreos, FritoLay Pringles, and Doritos Nacho Cheese Chips. Amounts of each food were selected to be a visually large amount of food far in excess of 30% of energy requirements for that age group71, i.e. total calories offered for 4-7y were approx. 1,581 kcal while total calories offered for 8-14y were approx. 3,746 kcal (for full details see Supplementary Tables 3 and for photograph of meal set-up see Supplementary Fig. 3). Food was weighed pre and post meal to calculate calorie intake.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). Data were primarily normally distributed according to Shapiro-Wilk tests, so parametric tests were used. Z-scores and accompanying percentiles for body mass index (BMI) were calculated using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] reference data from a US pediatric population54 from measured height and weight. Furthermore, weight groups were determined following CDC weight status categories72 with a BMI percentile greater than or equal to 85th and less than the 95th categorized as overweight, and a percentile equal to or greater than the 95th categorized as obesity. ANOVA was used to compare GABA+/Cr levels across weight status groups. Pearson’s correlations and independent samples t-tests were used to investigate relationships of GABA+/Cr levels and CEBQ Enjoyment of Food with age, sex and BMI z-score. Linear regressions were conducted to determine the degree to which GABA+/Cr and GSH/Cr levels in the dACC were associated with CEBQ Enjoyment of Food. Child age was used as a covariate due to significant correlation with Enjoyment of Food and previous findings of a positive association between GABA + levels and age in an overlapping sample63. Linear regressions were also used to determine the relationship between CEBQ Enjoyment of Food and meal test outcomes while controlling for age and sex. In addition, although our primary hypotheses concerned correlations with enduring eating behaviors rather than acute relationships between GABA concentrations and food intake, we conducted exploratory linear regressions to test relationships of GABA+/Cr and GSH/Cr levels in the dACC with meal test outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Schachter, S., Goldman, R. & Gordon, A. Effects of fear, food deprivation, and obesity on eating. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 10, 91–97 (1968).

Kininmonth, A. et al. The association between childhood adiposity and appetite assessed using the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire and Baby Eating Behavior Questionnaire: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews vol. 22 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13169

Derks, I. P. M. et al. Early childhood appetitive traits and eating disorder symptoms in adolescence: a 10-year longitudinal follow-up study in the Netherlands and the UK. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(23)00342-5 (2024).

Webber, L., Hill, C., Saxton, J., Van Jaarsveld, C. H. M. & Wardle, J. Eating behaviour and weight in children. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 33, 21–28 (2009).

Calisan Kinter, R. et al. The sensory profiles, eating behaviors, and quality of life of children with autism spectrum disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Psychiatr. Q. 95, 85–106 (2024).

Dovey, T. M., Kumari, V. & Blissett, J. Eating behaviour, behavioural problems and sensory profiles of children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), autistic spectrum disorders or picky eating: same or different? Eur. Psychiatry. 61, 56–62 (2019).

Sader, M. et al. Prevalence and characterization of Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in a Pediatric Population. JAACAP Open. 1, 116–127 (2023).

Wan, Z., Rolls, E. T., Cheng, W. & Feng, J. Sensation-seeking is related to functional connectivities of the medial orbitofrontal cortex with the anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage 215, (2020).

Shad, M. U. et al. Neurobiology of decision-making in adolescents. Behav. Brain. Res. 217, 67–76 (2011).

Umemoto, A., HajiHosseini, A., Yates, M. E. & Holroyd, C. B. Reward-based contextual learning supported by anterior cingulate cortex. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 17, 642–651 (2017).

Devinsky, O., Morrell, M. J. & Vogt, B. A. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain. 118 (Pt 1), 279–306 (1995).

Hogan, P. S., Galaro, J. K. & Chib, V. S. Roles of Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex and Anterior Cingulate in subjective valuation of prospective effort. Cereb. Cortex. 29, 4277–4290 (2019).

Posner, M. I., & Digirolamo, G. J. Executive Attention Conflict, Target Detection, and Cognitive Control. In the Attentive Brain 401–423. The MIT Press (1998)

Duncan, J. & Owen, A. M. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by Diverse Cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 23 (2000).

Jagtap, P. & Diwadkar, V. A. Effective connectivity of ascending and descending frontalthalamic pathways during sustained attention: Complex brain network interactions in adolescence. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 2557–2570 (2016).

Bakshi, N. et al. Inefficiently increased anterior cingulate modulation of cortical systems during working memory in young offspring of schizophrenia patients. J. Psychiatr Res. 45, 1067–1076 (2011).

Bush, G. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and attention networks. Neuropsychopharmacology vol. 35 278–300 Preprint at (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.120

Diwadkar, V. A. Adolescent risk pathways toward schizophrenia: Sustained attention and the brain. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 12, 2339–2347 (2012).

Paus, T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: Where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 417–424 (2001).

Bush, G. et al. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: A role in reward-based decision making. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, 523–528 (2002).

Jahn, A., Nee, D. E., Alexander, W. H. & Brown, J. W. Distinct regions of anterior cingulate cortex signal prediction and outcome evaluation. Neuroimage. 95, 80–89 (2014).

Carnell, S. et al. Neural correlates of familial obesity risk and overweight in adolescence. Neuroimage. 159, 236–247 (2017).

Syan, S. K. et al. Deficits in executive function and suppression of default mode network in obesity. Neuroimage Clin. 24, (2019).

Wang, H., Wen, B., Cheng, J. & Li, H. Brain structural differences between normal and obese adults and their links with lack of perseverance, negative urgency, and sensation seeking. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

Sadler, J. R. et al. Paediatric obesity and metabolic syndrome associations with cognition and the brain in youth: Current evidence and future directions. Pediatr. Obes. 18, e13042 (2023).

Carnell, S., Thapaliya, G., Jansen, E. & Chen, L. Biobehavioral susceptibility for obesity in childhood: Behavioral, genetic and neuroimaging studies of appetite. Physiol. Behav. 271, 114313 (2023).

Thapaliya, G. et al. Familial obesity risk and current excess weight influence brain structure in adolescents. Obesity. 29, 184–193 (2021).

Kennedy, J. T., Collins, P. F. & Luciana, M. Higher adolescent body Mass Index is Associated with Lower Regional Gray and White Matter volumes and lower levels of positive emotionality. Front. Neurosci. 10, 413 (2016).

Luo, S. et al. The role of maternal BMI on brain food cue reactivity in children: A preliminary study. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 2746–2755 (2021).

Eddy, K. T. et al. Neural activation of regions involved in food reward and cognitive control in young females with anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa versus healthy controls. Transl Psychiatry. 13, 220 (2023).

Ellison, Z. et al. Functional anatomy of calorie fear in anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 352, 1192 (1998).

Yau, P. L., Kang, E. H., Javier, D. C. & Convit, A. Preliminary evidence of cognitive and brain abnormalities in uncomplicated adolescent obesity. Obes. (Silver Spring). 22, 1865–1871 (2014).

Moreno-Lopez, L., Contreras-Rodriguez, O., Soriano-Mas, C., Stamatakis, E. A. & Verdejo-Garcia, A. Disrupted functional connectivity in adolescent obesity. Neuroimage Clin. 12, 262–268 (2016).

Song, S. et al. Brain structures associated with eating behaviors in normal-weight young females. Neuropsychologia 133, (2019).

Bohon, C. Brain response to taste in overweight children: A pilot feasibility study. PLoS One. 12, e0172604 (2017).

Harris, A. D., Saleh, M. G. & Edden, R. A. E. Edited 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo: Methods and metabolites. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine vol. 77 1377–1389 Preprint at (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26619

Mullins, P. G. et al. Current practice in the use of MEGA-PRESS spectroscopy for the detection of GABA. Neuroimage. 86, 43–52 (2014).

Saleh, M. G. et al. Simultaneous edited MRS of GABA and glutathione. Neuroimage. 142, 576–582 (2016).

Bezalel, V., Paz, R. & Tal, A. Inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms in the human cingulate-cortex support reinforcement learning: a functional proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuroimage. 184, 25–35 (2019).

Levar, N., Van Doesum, T. J., Denys, D. & Van Wingen, G. A. Anterior cingulate GABA and glutamate concentrations are associated with resting-state network connectivity. Sci. Rep. 9, (2019).

Silveri, M. M. et al. Frontal lobe γ-aminobutyric acid levels during adolescence: Associations with impulsivity and response inhibition. Biol. Psychiatry. 74, 296–304 (2013).

Prisciandaro, J. J. et al. Unique prefrontal GABA and glutamate disturbances in co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence. Transl Psychiatry 7, (2017).

Kim, H. J. et al. Associations between anterior cingulate cortex glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid concentrations and the harm avoidance temperament. Neurosci. Lett. 464, 103–107 (2009).

Weidacker, K., Johnston, S. J., Mullins, P. G., Boy, F. & Dymond, S. Impulsive decision-making and gambling severity: the influence of γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA) and glutamate-glutamine (glx). Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 32, 36–46 (2020).

Long, Z. et al. Decreased GABA levels in anterior cingulate cortex/medial prefrontal cortex in panic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 44, 131–135 (2013).

Park, S. et al. Shorter sleep duration is associated with lower GABA levels in the anterior cingulate cortex. Sleep. Med. 71, 1–7 (2020).

Sheth, C. et al. Reduced gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) and glutamine in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of veterans exposed to trauma. J. Affect. Disord. 248, 166–174 (2019).

Bhagwagar, Z. et al. Low GABA concentrations in occipital cortex and anterior cingulate cortex in medication-free, recovered depressed patients. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11, 255–260 (2008).

Gabbay, V. et al. Anterior cingulate cortex γ-aminobutyric acid deficits in youth with depression. Transl Psychiatry 7, (2017).

Bradley, K. A., Alonso, C. M., Mehra, L. M., Xu, J. & Gabbay, V. Elevated striatal γ-aminobutyric acid in youth with major depressive disorder HHS Public Access. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 86, 203–210 (2018).

Durazzo, T. C. & Meyerhoff, D. J. GABA concentrations in the anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices: associations with chronic cigarette smoking, neurocognition, and decision making. Addict. Biol. 26, (2021).

Janes, A. C. et al. GABA levels in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex associated with difficulty ignoring smoking-related cues in tobacco-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 38, 1113–1120 (2013).

Gazdzinski, S. et al. BMI and neuronal integrity in healthy, cognitively normal elderly: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Obesity. 18, 743–748 (2010).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Growth Charts. (2000). https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/cdc_charts.htm

Kaiser, L. F., Gruendler, T. O. J., Speck, O., Luettgau, L. & Jocham, G. Dissociable roles of cortical excitation-inhibition balance during patch-leaving versus value-guided decisions. Nat. Commun. 12, (2021).

Scholl, J. et al. Excitation and inhibition in anterior cingulate predict use of past experiences. Elife. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.20365.001 (2017).

Wang, G. Y. et al. ACC GABA levels are associated with functional activation and connectivity in the fronto-striatal network during interference inhibition in patients with borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage. 147, 164–174 (2017).

Puts, N. A. J. et al. Reduced GABA and altered somatosensory function in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 10, 608–619 (2017).

Oeltzschner, G. et al. Advanced Hadamard-encoded editing of seven low-concentration brain metabolites: principles of HERCULES. Neuroimage. 185, 181–190 (2019).

Kimin, L. S. et al. Children’s eating behaviour: a comparison between normal, overweight and obese children. Annals Med. Surg. 84, (2022).

Sleddens, E. F. C., Kremers, S. P. J. & Thijs, C. The children’s eating Behaviour Questionnaire: factorial validity and association with body Mass Index in Dutch children aged 6–7. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activity 5, (2008).

Carnell, S. & Wardle, J. Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: Validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite. 48, 104–113 (2007).

Saleh, M. G. et al. Effect of age on gaba1 and glutathione in a pediatric sample. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41, 1099–1104 (2020).

Stagg, C. J., Bachtiar, V. & Johansen-Berg, H. What are we measuring with GABA magnetic resonance spectroscopy? Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 573–575 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. MR quantitation of volume and diffusion changes in the developing brain. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 26, 45–49 (2005).

Wardle, J., Guthrie, C. A., Sanderson, S. & Rapoport, L. Development of the children’s eating behaviour questionnaire. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 42, 963–970 (2001).

Edden, R. A. E. et al. A batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid–edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 40, 1445–1452 (2014).

Öğütlü, H., Kaşak, M., Doğan, U., Zickgraf, H. F. & Türkçapar, M. H. Psychometric properties of the nine-item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen (NIAS) in Turkish children. J. Eat. Disord. 12, 30 (2024).

Birch, L. L., Fisher, J. O. & Davison, K. K. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 215–220 (2003).

Shomaker, L. B. et al. Links of adolescent- and parent-reported eating in the absence of hunger with observed eating in the absence of hunger. Obes. (Silver Spring). 21, 1243–1250 (2013).

United States Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. (2020).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Child and Teen BMI. (2022). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html#interpreted

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions are as follows: SD- formal analysis, writing- original draft, writing- review and editing, visualization; KS- formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing- review and editing; MS- methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing- review and editing; EJ- writing- review and editing; AP- investigation, project administration, writing- review and editing; YS- writing- review and editing, visualization; RE- conceptualization, methodology, writing- review and editing, supervision; SC- conceptualization, writing- original draft, writing- review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All parents and children older than 8 years old provided written informed consent and assent, respectively.

This project was funded by NIH grant R00DK088360 (PI: SC), a Johns Hopkins Discovery award (PI: SC), and a Baltimore (UMD-JHU) Diabetes Research Center P&F award (PI: SC) (P30DK079637), with additional support for SC and team from R01DK136602 (PI: SC), R01DK113286 (MPI: SC) and R01EB016189 (PI: RE), and support for imaging from P41 EB031771 to the Kirby Center for Functional Brain Imaging. Additional support for KRS from K01MH271178; MS from R00DA051315; and RE from R01 EB016089 and R01 EB023963.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duck, S.A., Smith, K.R., Saleh, M.G. et al. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) levels in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex are negatively associated with food motivation in a pediatric sample. Sci Rep 14, 24845 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75520-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75520-z