Abstract

We present a comprehensive study of buckled honeycomb germanene functionalized with alternately bonded side groups hydroxyl (–H), methyl (–CH3) and trifluoro methyl (–CF3). By means of most modern theoretical and computational methods we determine the atomic geometries versus the functionalizing groups. The quasiparticle excitation effects on the electronic structure are taken into account by means of exchange-correlation treatment within the GW framework. The Bethe–Salpeter equation is solved ab initio to derive optical spectra including excitonic and quasiparticle effects. Band edge excitons are investigated in detail. The binding properties are compared with those resulting from model studies. The functionalization leads to significantly modified band structures compared with pristine germanene. The Dirac bands near the K point are destroyed and direct gaps appear at the \(\Gamma\) point. Together with the many-body effects, quasiparticle gaps of 2.3, 1.8 or 1.0 eV result for –H, –CH3 and –CF3 functionalization. Totally different absorption spectra are found for in-plane and out-of-plane light polarization. Strongly bound excitons are visible below the quasiparticle band edge with binding energies of about 0.5, 0.4 or 0.3 eV. The nature of these band-gap excitons is investigated via their wave function, the contribution of various interband combinations and the dipole selection rules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) monoelemental group-IV materials beyond graphene1, the so-called Xenes, i.e. silicene, germanene and stanene, gained enormous interest because of their exotic properties and potential applications in novel electronic, optoelectronic or photovoltaic devices2,3,4. They have been mainly prepared by deposition on metal substrates5. In Xenes, a gap is opened by spin-orbit coupling (SOC) at the corner point K of the 2D hexagonal Brillouin zone (BZ), but it remains small2. Covalent functionalization with side groups, e.g. hydrogen –H, paves the way for significant tuning of their fundamental gap and, consequently, of their electronic and optical properties6.

A pronounced example is germanene, whose properties have been modified by many different side groups7,8,9,10, giving the possibility to imagine a large amount of different applications ranging from electronics to optical devices to solar cells to biomedical ones11. Recent investigations have shown that germanene can even be a promising anode material for lithium-ion batteries because of its high capacity and conductivity12,13. Unlike graphene, it cannot be exfoliated from bulk crystal. Its top-down synthesis is based on a chemical exfoliation of a Zintl phase by means of divalent ions, e.g. alkali earth metal ones Ca2+ 14. The chemical etching of the Ca2+ ions may lead to hydrogenated germanene, GeH2, where the Ge atoms in their buckled honeycomb arrangement are H-terminated in an alternating manner15,16 or even alkyl chains, e.g. methyl side groups –CH317, resulting in methyl-substituted germanene GeCH314,18,19. Fluorogermanene GeF is sometimes investigated20. In any case, the bonding to these side groups increases the tendency to a nonplanar \(sp^3\)-hybridized framework of Ge atoms with half of the side groups pointing below and the other half above the plane of the buckled 2D Ge layer. As an analogue to the methyl group, other side groups such as trifluoromethyl –CF39 are also under discussion. However, the replacement of the hydrogen by fluorine atoms in the –CF3 side group leads to expect significant differences because fluorine has a much higher electronegativity, 4.0, than carbon, 2.6, whereas hydrogen has a lower electronegativity, 2.2, than carbon, but higher than germanium (2.0)21. Many other different side-groups can also be studied for achieving significant fine tuning of the electronic properties of germanene22

Optical properties of hydrogenated, methyl-substituted or fluorinated germanene have been studied in a few theory papers applying approximate19 or full many-body approaches20,23,24,25,26,27. In a full many-body treatment, the single-quasiparticle excitation aspect is taken into account within the GW framework, while the electron-hole interactions, the excitonic effects, are described solving the Bethe–Salpeter equation (BSE) for the two-particle response functions28. From the experimental side, optical properties of germanane, methylgermanane or fluorogermanane have been investigated by different spectroscopies: fluorescence7,29, absorbance8,10,14 or time-resolved photoluminescence17.

Nevertheless, a clear and systematic study of the spectrally resolved optical conductivities including the dependence on light polarization and many-body effects, as well as the spectrum-band structure relation, are missing. Thermodynamic and thermoelectric studies of functionalized germanene layers are limited to the GeCH3 case30.

In the current manuscript we investigate the favored atomic geometries of buckled 2D germanene with various side groups –H, –CH3 and –CF3 and their relation to the electronic structures, the optical conductivities, and the electron-hole-pair excitations, the excitons. The theoretical and numerical methods used are described in the following section. Then the structural data are presented and discussed together with the resulting band structures in GW quality, whereas the optical spectra including many-body effects and the bound excitons below the absorption edge are described in the last section. Finally, a summary and conclusions are given.

Theoretical and numerical methods

The atomic geometries and the starting electronic structures are calculated in the framework of the density functional theory (DFT)31,32. We use the QUANTUM ESPRESSO package33,34 with the semilocal Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation (XC) functional35. The electron-ion interaction is described by normconserving pseudopotentials28 taking the valence s and/or p electrons of Ge, C, F and H atoms as well as the semicore Ge 3d electrons into account. The single-particle wave functions are expanded in plane waves up to a cutoff of 90 Ry. The cutoff has been carefully tested to converge the total energies. A superlattice arrangement is applied to simulate the isolated 2D objects with their thickness of about 2.5 Å and 25 Å vacuum in between. Two Ge atoms and two sidegroups –H, –CH3 and –CF3 are arranged in a lateral hexagonal unit cell in an alternating manner to keep the honeycomb symmetry of basal plane of the buckled germanene. The BZ sampling is performed with a 21\(\times\)21\(\times\)1 Monkhorst–Pack (MP) \(\textbf{k}\)-point grid centered at \(\Gamma\)36.

The many-body quasiparticle (QP) effects on the original Kohn-Sham (KS) band energies32 are described within a well-converged G0W0 treatment28. The screened Coulomb interaction is computed with a 54\(\times\)54\(\times\)1 k-point grid and up to 400 empty bands. In the correlation part of the self-energy \(\Sigma _c\) we use 6000 plane waves, whereas in the exchange part \(\Sigma _x\) we use 30000 plane waves. The GW corrections are explicitly computed at 76 k-points in the 2D BZ for four valence and four conduction bands. Additionally, more precise computations were performed at five high-symmetry points in the 2D BZ and nine valence and nine conduction bands. The GW corrections for arbitrary \(\textbf{k}\)-points and bands are finally obtained by an interpolation technique using cubic splines.

The calculations of the single-particle optical and dielectric properties are performed with a dense 120\(\times\)120\(\times\)1 \(\textbf{k}\)-point mesh and 400 bands. Together with a Gaussian convolution with a broadening parameter of 0.1 eV, this mesh gives excellent spectra within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA). The dielectric function tensor of the superlattice arrangement is applied to derive the tensor of the optical conductivities with the in-plane and out-of-plane components \(\sigma _{\parallel }(\omega )\) and \(\sigma _\bot (\omega )\), respectively37. Details are given in the Supplementary Material, section II. The low-frequency behavior of the in-plane component is used to calculate the static electronic polarizability \(\alpha _\textrm{2D}\) as2:

It is determined within the independent-particle regime by means of the KS eigenvalues and eigenfunctions38 and used to calculate the excitonic binding energies and radii within the Rytova–Keldysh model39,40.

Based on the G0W0 calculation for QP band eigenvalues and independent-particle screening of the Coulomb attraction, the BSE for the optical response function is solved. We apply the EXC code41, where the homogeneous BSE is solved within the Tamm-Dancoff approximation and with a BSE kernel containing the statically screened electron-hole attraction and the repulsive unscreened electron-hole exchange interaction28. The bands involved in the optical transitions are restricted to four occupied and four empty bands, giving excitonic spectra converged till 5 eV. A 54\(\times\)54\(\times\)1 \(\textbf{k}\)-point mesh is applied to obtain converged absorption spectra. The Coulomb matrix elements in Fourier space take 1005 reciprocal lattice vectors into account. A cutoff of the long-range Coulomb potential is introduced to avoid the interaction between excited particles in 2D objects in different supercells.

Structural and electronic properties

Atomic geometries

Figure 1 displays the optimized atomic structures of germanene functionalized with the side groups –H, –CH3 and –CF3, i.e., germanane, methyl-germanane and a structurally analogue material, where the methyl group is substituted by the trifluoromethyl one. The point-group symmetry with the three different side groups arranged on the buckled honeycomb structure is slightly reduced from \(D_{3d}\) for germanane to \(D_3\) for the more complex ligands. Thereby, the energy optimization leads to the high-symmetry orientation of the methyl groups. We have also considered lower symmetries such as the C2h group realized by the hydroxyl –OH or benzyl –C6H5 ligands. However, because of the resulting too small gap (–OH) or the complexity for many-body calculations (–C6H5) we did not further follow the functionalization with these side groups. A small gap also results for the pure –F side group, the fluorogermanene with \(D_{3d}\) symmetry42.

The structural parameters of GeH, GeCH3 and GeCF3 are listed in Table 1. For the purpose of comparison also characteristic lengths of clean germanene and fluorogermanene are given. The parameters of the latter ones are in close agreement with other DFT-PBE results2. The lattice constant a exhibits an increase from Ge to GeCF3 with the size of side group –H, –F, and –CF3. The largest bucklings show that the transition from the \(sp^2\) to the \(sp^3\) bonding fully develops for the larger ligands. A similar trend is visible for the bond lengths \(d_\mathrm{Ge-X}\) of a Ge atom in the basal plane and the central atom X = H, F, C. The bond lengths \(d_\mathrm{Ge-X}\) and \(d_\mathrm{C-Y}\) (Y = H, F) are in good agreement with the sum of the corresponding covalent radii \(r_\textrm{Ge}=\) 1.22 Å, \(r_\textrm{C}=\) 0.77 Å, and \(r_\textrm{H}=\) 0.32 Å21. In the cases where fluorine (\(r_\textrm{F}=\) 0.72 Å) is involved, instead, its larger electronegativity adds a polar contribution to the bond and makes it stronger. Despite their bonding to the germanene basal layer, the tetrahedra –CH3 and –CF3 possess angles which are close to those of an ideal bonding tetrahedron with a tetrahedron angle of 109.47° and a dihedral one of 70.53°.

Band structures

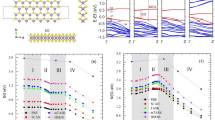

The quasiparticle band structures of GeH, GeCH3 and GeCF3 are displayed in Fig. 2. For comparison and characterization of the QP effects, also the KS bands are shown. The side groups have a drastic effect on the bands known from the clean buckled germanene basal plane, in the region of the fundamental gap between valence and conduction bands2. The Dirac cones at the K points are destroyed and a huge gap of the order of 6–7 eV (in DFT) is there opened. In Fig. SM1 in the Supplementary Material the localization of the corresponding band states is illustrated. The direct gap of the functionalized germanene systems appears at the \(\Gamma\) point. The two highest valence bands form at \(\Gamma\) a twofold (fourfold with spin polarization) state, while still a non-degenerate (without spin) conduction band remains. In the GeH and GeCH3 cases also the known lower valence bands forming a Dirac cone near −8 eV remain, while different bands due to the side group are visible for GeCF3. However, two compressed Dirac cones are still visible in GeCF3 at K at approximately −6 and −8 eV. In general, the uppermost two Ge-derived dispersive valence bands cross below the VBM and are modified by rather dispersionless bands related to the side groups. Moreover, the lowest conduction band, its energy position and dispersion, remains similar for the three functionalized systems, especially with a pronounced conduction band second minimum at M above a local maximum in the highest valence band. Mainly the lower groups of valence bands are influenced by the –CH3 and –CF3 side groups.

Quasiparticle GW band structures (red lines) of (a) GeH, (b) GeCH3 and (c) GeCF3 are plotted along high-symmetry lines in the hexagonal BZ of the underlying honeycomb lattice. For comparison also the corresponding DFT bands (thin black lines) are shown. The GW density of states (in arbitrary units) is reported in the right part of the panels. The VBM is used as energy zero and as alignment level for the band structures calculated within the DFT-PBE and the GW approaches.

Figure 2 illustrates the strength of the QP shifts. After the alignment of the GW and DFT band structures at the VBM, the QP effects on the valence bands related to the germanene basal planes are small. They lead, however, to significant shifts of the rather weakly dispersive bands derived from orbitals at the side-group atoms. This is especially true for the flat bands between −5 and −6 eV (−3 and −4 eV) in the GeCH3 (GeCF3) case, where QP shifts of the order of 1 eV toward larger binding energies are observable. The lowest germanene-related conduction bands show QP shifts of about 1.3 (GeH), 1.1 (GeCH3) or 0.7 (GeCF3) eV toward higher energies with respect to an alignment of VBM in DFT and QP approach. These shifts exhibit a wave-vector dispersion with maximum (minimum) values near K (\(\Gamma\)). The average QP shifts of the lowest conduction band amount to 1.8, 1.8 and 1.3 eV for the three materials. In previous GW calculations similar valence bands and energy gaps have been observed for GeH20,23,27. Interpreting the GW shifts and the modified band widths, one has to take into account the chemical nature and the localization of the wave functions. In all three functionalized 2D crystals the uppermost three valence bands exhibit an increase of the bandwidth due to the GW shifts toward deeper energies, i.e. stronger binding energies. According to Fig. SM1, the corresponding mostly p-like band states are mainly localized in the germanene basal plane. The two lower more Ge s-like bands show, at least for GeCH3, an increased GW shift toward lower energies. The deeper valence bands with wave functions from the side groups show somewhat larger GW shifts due to their localization in or around the side groups. In all cases, the wave-vector dependence of the QP shifts is much larger for the lowest conduction band than for the uppermost valence bands.

It seems that a scissors-operator approximation28 would not be sufficiently accurate for any of the three functionalized germanenes. The GW shifts toward higher energies in the conduction bands depend on the band index and the band dispersion. This is obvious comparing the lowest conduction band with the higher ones.

The dispersion of the uppermost valence bands and lowest conduction bands in Fig. 2 show minima and maxima at the high-symmetry points \(\Gamma\), M, and K but also on the \(\Gamma M\) high-symmetry line. This fact should lead to van Hove singularities of different character in the interband density of states (DOS) near the QP gaps at \(\Gamma\) listed in Table 2 but also at higher energies near 4.5 (4.6, 3.7) eV on \(\Gamma M\) line, 5.1 (4.5, 4.0) eV at M or 9.4 (9.3, 7.7) eV at K for GeH (GeCH3, GeCF3). Apart from excitonic effects they will be important for understanding the spectral behavior of the absorption discussed below.

Band parameters: gaps and effective masses

The direct gaps \(E_g\) visible in Fig. 2 are listed in Table 2 with (QP) and without (DFT) quasiparticle corrections in GW approximation. In the germanane case the gap values of \(E_g=\) 1.02 eV (DFT) and \(E_g=\) 2.29 eV (QP) are in almost agreement with other calculations16,20,23,24,27, especially with the values in Refs.24,27. Discrepancies are induced by the use of the local-density approximation for XC32 in the DFT case or different approaches and convergence stages to compute the QP gap corrections within GW. Experimental values show somewhat smaller values, 1.8 eV from photothermal deflection spectroscopy but lower values in photoluminescence14,43. One reason for the values smaller than the GW values is related to excitonic effects, which we will discuss later but here illustrated by the optical gap \(E_g\)(opt). Another reason may be related to a not complete hydrogenation of germanene in experiments. The functionalization with –CH3 (–CF3) leads to somewhat smaller gap values in Table 2 compared to the effect of the –H side group. It can be observed that the gap trend is inversely related to that of the lattice constant, reported in Table 1.

Other electronic structure parameters as electron (hole) masses \(m_e\) (\(m_h\)) defined by the dispersion of the lowest conduction and the two highest valence bands around \(\Gamma\) are listed in Table 3.

Only a small \(\textbf{k}\)-point region around \(\Gamma\) is chosen, of radius of 0.1 \(a_B^{-1}\) (with \(a_B\) as the Bohr radius of a hydrogen atom), to make a parabolic fit to the KS bands displayed in Fig. 2. Surprisingly, we do not find a mentionable mass anisotropy along the directions \(\Gamma M\) and \(\Gamma K\) in this small surrounding around \(\Gamma\). However, we have to mention the sensitivity of the mass sizes to the chosen fit interval. Larger surroundings around \(\Gamma\) tend to give rise to larger mass values. For the effective masses \(m_e\) of the electrons and light holes \(m_{lh}\) (from the second valence band) we find extremely small values around 0.05 m (with m the free electron mass) or lower. The heavy hole masses \(m_{hh}\) from the highest valence bands are by one order of magnitude larger. There are pronounced chemical trends with decreasing masses \(m_e\) and \(m_{lh}\) and slightly increasing heavy-hole ones \(m_{hh}\) along the side groups –H, –CH3 and –CF3.

Optical spectra and excitonic effects

Single-particle spectra and van Hove singularities

The optical properties of the freestanding 2D crystals, here the chemically functionalized germanene sheets, are ruled by the optical conductivity tensor for light polarization parallel or perpendicular to the basal plane37. Its relation to the frequency-dependent dielectric tensor of the superlattice arrangement of the 2D crystals is given in Eqs. (SM1) and (SM2) in the Supplemental Material. The real and imaginary parts of the frequency-dependent conductivity are displayed in Fig. 3. They have been calculated within the independent-particle approximation38, also called random phase approximation, i.e. without excitonic and quasiparticle effects, and illustrate the optical absorption and dielectric properties for in-plane and out-of-plane light polarization in a wide range of photon energies \(\hbar \omega\). The real parts clearly show the absorption edges, which are given by the DFT band gaps in Table 2 at least for in-plane polarization. The corresponding spectra for out-of-plane polarization are shifted to higher photon energies, because of local-field effects discussed elsewhere37,44,45 and especially the low-energy optical transitions of \(\pi \rightarrow \pi ^*\) character, which are almost forbidden for perpendicular polarization.

Single particle calculation: real part (left panels) and imaginary part (right panels) of the optical conductivity versus photon energy of (a–b) GeH, (c–d) GeCH3 and (e–f) GeCF3 for in-plane (\(\parallel\)) (blue lines) and out-of-plane (\(\bot\)) (red lines). The spectra are normalized to the conductance quantum \(\sigma _0\)37.

The \(\sigma _\parallel (\omega )\) spectra in Fig. 3 exhibit spectral features, e.g. peak structures, near the van Hove singularities already discussed in the paragraph on the electronic properties. The lowest-energy major peaks in the in-plane absorption spectra \(Re \sigma _\parallel (\omega )\) are located at a position slightly below \(\hbar \omega =\) 4 eV independent of the side group. The main contributions are due to transitions near the M point and on the \(\Gamma M\) line indicated by the pronounced minimum in the lowest conduction band. Transitions at \(\Gamma\) from the highest valence bands into the second and higher conduction bands in the same energy range possess a low oscillator strength because of the germanene-derived character of the valence bands but the localization of the conduction states at the side groups. The next peak somewhat below \(\hbar \omega =\) 8 eV is mainly due to transitions around K between states related to the side groups. In the case of the out-of-plane polarization the absorption edge is significantly blueshifted to photon energies above \(\hbar \omega =\) 4 eV, even in the RPA spectra. These shifted spectra show van Hove singularities in the higher energy range. The peak intensities in \(\sigma _\bot (\omega )\) are of the same order of magnitude as in \(\sigma _\parallel (\omega )\) as in the case of other 2D crystals38. Near the singularities in the absorption spectra, the imaginary parts of the optical conductivities exhibit zeros. They are most pronounced in \(Im\sigma _\bot (\omega )\) for GeH and GeCH3, indicating strong plasmon-like excitations in the resulting energy loss functions (not shown). Independent of the side group, all these spectra emerge with negative values linearly increasing to vanishing values for vanishing frequencies. Their linear behavior allows to extract the static electronic polarizability \(\alpha _\textrm{2D}\) from Eq. (1). The resulting values are listed in Table 3. They are in the range of other 2D materials with similar gaps29 but are smaller than for Xenes with extremely small gaps2,46. Indeed, an analytical model gives \(\alpha _\textrm{2D}=2e^2/(3\pi E_g)\)2 and, consequently with the DFT gaps in Table 2, \(\alpha _\textrm{2D}=\)3.00 Å (GeH), 4.05 Å (GeCH3), and 10.28 Å (GeCF3). These values are close to the ab initio estimated ones in Table 3.

Many-body effects on absorption spectra

The effects of the quasiparticle shifts in the GW framework and the excitonic effects considered solving the BSE for the optical response function are illustrated in the Supplemental Material in Fig. SM2 for the real part of the optical conductivity \(\sigma _\parallel (\omega )\) with in-plane light polarization.

In general, one observes similar qualitative effects as found for other 2D systems2,23,47. As already mentioned, the optical response functions calculated within the independent-particle approximation, here called RPA, where only Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the DFT are used, exhibit low-energy absorption edges and the occurrence of van Hove singularities at higher energies with pronounced peaks around \(\hbar \omega =\) 3 eV, mainly due to transitions near M and the \(\Gamma M\) line of the Brillouin zone.

The quasiparticle effects treated within the GW approximation give rise to general blue shifts of the entire spectrum by about 1.5–2.0 eV for GeH and GeCH3 or 1.0–1.5 eV for GeCF3. However, the effect on the lineshape remains small. Including the excitonic effects there is a tendency for a somewhat smaller redshift with the tendency to recovering the peak positions in the RPA spectra. The inclusion of excitonic effects is accompanied by an increase of the oscillator strengths and, hence, the formation of strong peaks at the absorption edges, which will be discussed below.

The many-body effects are most important for the position and the lineshape of the absorption edges. The results of the solution of the homogeneous BSE based on quasiparticle eigenvalues in GW quality and KS wave functions are plotted in Fig. 4a. Again the strong blue shifts of the edges for out-of-plane light polarization compared to those for in-plane light polarization are visible, together with a large reduction of the intensity of the out-of-plane component due to local-field effects. Most important, however, is the appearance of optical absorption by bound excitons with two-particle excitation energies below the QP gaps \(E_g\)(QP). Its position can be interpreted as optical gap \(E_g\)(opt) of the corresponding 2D material. The difference of the two gaps \(E_B=E_g\mathrm{(QP)}-E_g\)(opt) delivers the characteristic binding energy \(E_B\) of the lowest-energy bound excitons below the QP absorption edge. All these values are also listed in Table 2. The complete set of bound excitonic states is listed in the Supplementary Material in Table SMI.

Excitonic calculation: (a) 2D in-plane (blue line) and out-of-plane (red line) optical conductivities of GeH, GeCH3 and GeCF3 near the corresponding absorption edges. The position of the quasiparticle gap in GW quality is indicated by a vertical dashed line. (b) Bound exciton peaks within the fundamental gap. Contributions from various bright exciton bound states are indicated by red vertical lines. In all panels, the blue and red curves give the spectra after Lorentzian convolution with a 0.1 eV broadening. The spectral coverage from IR through visible light up to UV is indicated by colored horizontal stripes. All spectra are normalized to the dc conductivity.

For germanane GeH our results are in excellent agreement with the GW+BSE studies of27 who report \(E_g\mathrm{(opt)}=\) 1.87 eV and \(E_B=\) 0.56 eV, whereas other studies deliver values fluctuating around ours with \(E_g\mathrm{(opt)}=\) 2.06, 1.8, 1.45 eV and \(E_B=\) 0.75, 0.6, 0.92 eV20,23,24. The gap values and the binding energies for the other two functionalized germanene layers GeCH3 and GeCF3 are drastically reduced because of the increase of the screening due to the larger side groups as described by the 2D static electronic polarizability \(\alpha _\textrm{2D}\) (see Table 3). The majority of experimental values seems to tend to optical gaps of the order of magnitude of the computed ones. The absorption edge is found to be 1.66 eV (GeH) and 1.76 eV (GeCH3) for exfoliated layers8. Fluorescence measurements of methyl-functionalized germanene exhibit peak maxima close to 2 eV29. Time-resolved photoluminescence show an above-band-gap emission at 1.97 eV, while the band gap should be 1.62 eV17. However, multilayer stacks have been investigated, which are influenced by some hydrogen intercalation or hydration. Absorbance measurements estimate a fundamental gap of GeH in the range of \(E_g\mathrm{(opt)}=\) 1.4-1.6 eV14,48,49. Previously reported measurements of thin films of GeH proposed a direct gap of 1.8 eV from photothermal deflection spectroscopy but found photoluminescence at 0.45 or 1.35 eV43, an energy range for which no luminescence has been observed in later studies14 and also much below of the predicted interband distances.

Analysis of band-edge excitons

In order to better understand the origin of the bound exciton peak below the QP gap \(E_g\)(QP) in Fig. 4a, this peak in the \(Re\sigma _\parallel (\omega )\) spectra is displayed in more detail in Fig. 4b. In particular, the broad peak generated with a Lorentzian broadening of 0.1 eV is resolved by a series of dipole-allowed excitons with almost decreasing (toward higher energies) oscillator strengths as indicated by the vertical lines within the broad peak. The peak, especially its position and intensity, is dominated by the dipole-allowed lowest-energy electron-hole-pair excitation with an energy close to the values \(E_g\)(opt) listed in Table 2. In all cases, GeH, GeCH3 and GeCF3, the peak maximum is dominated by a bright exciton degenerate with a dark exciton. This excitonic excitation is built by a mixing of transitions from the top two valence bands to the bottom of the lowest conduction band in a k-region around \(\Gamma\). For GeCH3 and GeCF3 the main peak is also followed by a series of bound states, which however significantly deviate from the 2D hydrogenic Rydberg series of s-like excitons, where the electrons and holes are attracted by a statically screened Coulomb potential. Such a behavior of nonhydrogenic exciton states is explained in the literature by a non-local screening50,51,52,53. In addition to the exciton binding energy \(E_B\) (see Tables 2 and 3) the character of the first excitonic bound state can be best illustrated by its two-particle wave function in real space. Its square modulus \(\left| \Psi (\textbf{x}_e,\textbf{x}_h=R_\textrm{GeGe})\right| ^2\) is displayed in Fig. 5 for the three functionalized germanene layers under consideration. Thereby, because of the heavy holes with a mass larger by a factor 10 than the electron mass, the hole motion can be neglected. The hole is assumed to be localized in the middle of a bonding state along a Ge–Ge bond in the basal plane, \(R_\textrm{GeGe}\), so that a wave function square modulus in Fig. 5 gives the probability function to find an electron in the surroundings of the hole localized in a Ge-Ge bond center. The lateral extent of the wave function only weakly varies with the functional group –H, –CH3 or –CF3. However, while for GeH and GeCF3 the vertical extent of the wave function is almost restricted to the germanene basal plane, it is also spread over the functional groups in the GeCH3 case. The excitonic wave function is used to calculate an average excitonic radius \(r_\textrm{exc}\) according to the procedure described in Ref.47. It characterizes the average distance between electron and hole in the internal motion of the corresponding two-particle excitation. The resulting ab initio values \(r_\textrm{exc}\) = 15.9, 16.7 and 18.5 Å do not vary much with the side group.

The ab initio calculated values \(r_\textrm{exc}\) in Table 3 are much larger than the Ge–Ge bond length in the basal plane that is a fraction of the 2D lattice constant (see Table 1). This fact indicates that in reciprocal space only a small \(\textbf{k}\)-region around \(\Gamma\) contributes. Consequently, the kinetic energy of the internal motion of the electron-hole pair can be described in effective-mass approximation (EMA) through \(\frac{\hbar ^2}{2\mu }k^2\) where the interband mass \(\mu\) is given by \(\frac{1}{\mu }=\frac{1}{m_e}+\frac{1}{m_h}\) with the electron mass \(m_e\) from Table 3. The hole mass \(m_h\) could be the heavy hole one \(m_{hh}\) or some combination with the light hole one \(m_{lh}\). To account for the non-local screening of the electron-hole attraction we apply the Rytova–Keldysh potential39,40, whose screening is ruled by the 2D static electronic polarizability \(\alpha _{2D}\)2. In the free-standing case this screened potential varies between a logarithmic behavior with the electron-hole distance and the bare 2D Coulomb potential, depending on the material. Assuming a 2D 1s-like wave function, the exciton binding energy and the excitonic radius, \(E^\textrm{mod}_B\) and \(r^\textrm{mod}_\textrm{ex}\), of this model can be described by analytical formulas2,25,46,47. The results are also listed in Table 3 when choosing \(m_h=m_{hh}\) and \(m_h=(m_{hh}+m_{lh})/2\) to model the contribution of only the upper valence band or both upper valence bands. The exact hole mass value does not really play a role, since the reduced mass is dominated by the electron mass, \(\mu \approx m_e\). The model gives binding energies \(E^\textrm{mod}_B\) in excellent agreement with the ab initio calculated values \(E_B\). The excitonic radii, however, seem to be slightly overestimated by the model. In any case, these results suggest that the lowest-energy excitons in the functionalized germanene layers can be analytically described with a kinetic energy as those of the Wannier-Mott excitons28 and a 2D Coulomb potential that is screened by a function \((1+2\pi \alpha _\textrm{2D}q)\) in reciprocal \(\textbf{q}\)-space.

Summary and conclusions

By means of state of the art theories based on first principles, the density functional theory for the ground state and the many-body perturbation theory for one- and two-particle electronic excitations, we have investigated the bonding behavior, the atomic geometries, the quasiparticle band structures, and the optical properties, including excitonic effects, of a new class of 2D materials based on the functionalization of germanene layers with different side groups –H, –CH3 and –CF3. The resulting geometries and electronic structures show that the arrangement of Ge atoms in the germanene basal plane almost survives independent of the side group. However, the functionalizations destroy the Dirac bands near the K points and lead to an opening of large gaps, whose band edges are dominated by the electronic side-group states, while the bands around the \(\Gamma\) point, forming the fundamental gap of functionalized germanene, are dominated by electronic wave functions localized in the basal plane. The gap values decrease along the series –H, –CH3 and –CF3 in accordance with the bond strength to the side group centres X = H or C, expressed by the bond length and its ionicity, i.e., the degree of electron transfer between the central side group atom and the neighbored Ge atom.

Many-body effects dominate the electronic and optical properties. The quasiparticle effects open the KS gap at \(\Gamma\) by factors of 2–3 . The excitonic interactions affect the optical spectra by a tendency to partially compensate the blue shifts due to the QP effects. The optical gaps, characterizing the true absorption edges, are redshifted toward the red (GeH), near infrared (GeCH3), or the mid-infrared (GeCF3). The screened electron-hole attraction leads to the formation of exciton bound states, which enhance the effective optical oscillator strengths and make the emission lines more narrow in comparison to the case without these effects. Finally, we have demonstrated that the bound excitons can be interpreted as 2D Wannier–Mott excitons with spatial extents larger than the typical lateral bond length but with a screened interaction that may be described by Rytova–Keldysh-type potentials.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1849 (2007).

Bechstedt, F., Gori, P. & Pulci, O. Beyond graphene: Clean, hydrogenated and halogenated silicene, germanene, stanene, and plumbene. Prog. Surf. Sci. 96, 100615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progsurf.2021.100615 (2021).

Gori, P., Bechstedt, F. & Pulci, O. Xenes: 2D synthetic materials beyond graphene, chap. Optical properties of Xenes, 319 (Elsevier Cambridge, 2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Covalent bonded bilayers from germanene and stanene with topological giant capacitance effects. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 7, 27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-023-00381-5 (2023).

Yuhara, J. & Le Lay, G. Beyond silicene: Synthesis of germanene, stanene and plumbene. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59(SN), SN0801. https://doi.org/10.35848/1347-4065/ab8410 (2020).

Rosli, N. F. et al. Siloxene, germanane, and methylgermanane: Functionalized 2D materials of group 14 for electrochemical applications. Adv. Func. Mater. 30, 1910186. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201910186 (2020).

Sturala, J., Luxa, J., Matějková, S., Sofer, Z. & Pumera, M. Germanane synthesis with simultaneous covalent functionalization: towards highly functionalized fluorescent germananes. Nanoscale 11, 19327. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR04081A (2019).

Ng, S. et al. Two-dimensional functionalized germananes as photoelectrocatalysts. ACS Nano 15, 11681. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c02327 (2021).

Hartman, T., Konečný, J., Mazánek, V., Šturala, J. & Sofer, Z. A decade of germananes: Four approaches to their functionalization. Inorg. Chem. 61, 12425. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c01873 (2022).

Konečný, J. et al. Photomodification of benzyl germanane with group 6 metal carbonyls. FlatChem 33, 100354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flatc.2022.100354 (2022).

Zhao, F., Feng, Y. & Feng, W. Germanium-based monoelemental and binary two-dimensional materials: Theoretical and experimental investigations and promising applications. InfoMat 4, e12365. https://doi.org/10.1002/inf2.12365 (2022).

Loaiza, L. C., Monconduit, L. & Seznec, V. Si and Ge-based anode materials for Li-, Na-, and K-ion batteries: A perspective from structure to electrochemical mechanism. Small 16, 1905260. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201905260 (2020).

Wei, S. et al. Reaction mechanism and performance of innovative 2D germanane-silicane alloys: Si\(_{x}\)Ge\(_{1-x}\)H electrodes in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci.. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202308955 (2024).

Bianco, E. et al. Stability and exfoliation of germanane: A germanium graphane analogue. ACS Nano 7, 4414. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn4009406 (2013).

Voon, L. C. L. Y., Sandberg, E., Aga, R. S. & Farajian, A. A. Hydrogen compounds of group-IV nanosheets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 163114. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3495786 (2010).

Houssa, M. et al. Electronic properties of hydrogenated silicene and germanene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 223107. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3595682 (2011).

Cinquanta, E. et al. Dynamics of two distinct exciton populations in methyl-functionalized germanane. Nano Lett. 22, 1183. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c04357 (2022).

Ma, Y., Dai, Y., Wei, W., Huang, B. & Whangbo, M.-H. Strain-induced quantum spin Hall effect in methyl-substituted germanane GeCH3. Sci. Rep. 4, 7297. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07297 (2014).

Jing, Y., Zhang, X., Wu, D., Zhao, X. & Zhou, Z. High carrier mobility and pronounced light absorption in methyl-terminated germanene: Insights from first-principles computations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4252–4258. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01848 (2015).

Shu, H., Li, Y., Wang, S. & Wang, J. Quasi-particle energies and optical excitations of hydrogenated and fluorinated germanene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 4542. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP05146G (2015).

Sargent, W. Table of periodic properties of the elements (Skokie (Ill.), 1980).

Denis, P. A., Laranjeira, J. A. S. & Sambrano, J. R. Covalent functionalization of germanene employing computational simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4CP00476K (2024).

Pulci, O. et al. Strong excitons in novel two-dimensional crystals: Silicane and germanane. Europhys. Lett. 98, 37004. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/98/37004 (2012).

Wei, W., Dai, Y., Huang, B. & Jacob, T. Many-body effects in silicene, silicane, germanene and germanane. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 8789. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP51078F (2013).

Pulci, O. Excitons in two-dimensional sheets with honeycomb symmetry.. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 252, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201350404 (2014).

Dien, V. K., Li, W.-B., Lin, K.-I., Han, N. T. & Lin, M.-F. Electronic and optical properties of graphene, silicene, germanene, and their semi-hydrogenated systems. RSC Adv. 12, 34851. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA06722F (2022).

Zaabar, F., Mahrouche, F., Mahtout, S., Rabilloud, F. & Rezouali, K. Effects of an external electric field on the electronic properties and optical excitations of germanane and silicane monolayers. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 35, 175502. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/acbe25 (2023).

Bechstedt, F. Many-body approach to electronic excitations (Springer, 2016).

Ang, W. L., Sturala, J., Antonatos, N., Sofer, Z. & Bonanni, A. Effect of surface chemistry on bio-conjugation and bio-recognition abilities of 2D germanene materials. Nanoscale 13, 1893. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NR07579E (2021).

Abdi, M. & Astinchap, B. Investigating the magnetic, thermoelectric, and thermodynamic properties of the GeCH3 single-layer considering external magnetic field, doping, and strain. Sci. Rep. 13, 1598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28430-5 (2023).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.136.b864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.140.a1133 (1965).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 465901. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648x/aa8f79 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.13.5188 (1976).

Matthes, L., Pulci, O. & Bechstedt, F. Influence of out-of-plane response on optical properties of two-dimensional materials: First principles approach. Phys. Rev. B. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.94.205408 (2016).

Adolph, B., Gavrilenko, V. I., Tenelsen, K., Bechstedt, F. & Sole, R. D. Nonlocality and many-body effects in the optical properties of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 53, 9797. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.53.9797 (1996).

Rytova, N. S. Screened potential of a point charge in a thin film. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1806.00976 (2018).

Keldysh, L. Coulomb interaction in thin semiconductor and semimetal films. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 29, 658 (1979).

Reining, L., Olevano, V., Sottile, F., Albrecht, S. & Onida, G. EXC is an exciton code working in reciprocal space, frequency domain, and using plane waves basis. http://etsf.polytechnique.fr/exc.

Ma, Y., Dai, Y., Niu, C. & Huang, B. Halogenated two-dimensional germanium: candidate materials for being of quantum spin Hall state. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 12587. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2JM30960B (2012).

Vogg, G., Meyer, A.J.-P., Miesner, C., Brandt, M. S. & Stutzmann, M. Efficient tunable luminescence of SiGe alloy sheet polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3956. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1378315 (2001).

Marinopoulos, A. G. et al. Optical absorption and electron energy loss spectra of carbon and boron nitride nanotubes: a first-principles approach. Appl. Phys. A 78, 1157–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-003-2467-z (2004).

Guilhon, I. et al. Out-of-plane excitons in two-dimensional crystals. Phys. Rev. B. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.99.161201 (2019).

Pulci, O., Gori, P., Grassano, D., D' Alessandro, M. & Bechstedt, F. Transitions in Xenes between excitonic, topological and trivial insulator phases: Influence of screening, band dispersion and external electric field. SciPost Phys. 78, 025, https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhys.15.1.025 (2023).

Prete, M. S. et al. Giant excitonic absorption and emission in two-dimensional group-III nitrides. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67667-2 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. GeH: A novel material as a visible-light driven photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Chem. Commun. 50, 11046–11048. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CC03636K (2014).

Giousis, T. et al. Synthesis of 2D germanane (GeH): A new, fast, and facile approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202010404 (2021).

Chernikov, A. et al. Exciton binding energy and nonhydrogenic Rydberg series in monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 076802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.076802 (2014).

Qiu, D. Y., da Jornada, F. H. & Louie, S. G. Screening and many-body effects in two-dimensional crystals: Monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235435. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.235435 (2016).

Pedersen, T. G. Stark effect in nonhydrogenic low-dimensional excitons. Phys. Rev. B 107, 195419. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.107.195419 (2023).

Li, W.-H. et al. The key role of non-local screening in the environment-insensitive exciton fine structures of transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Nanomaterials 13, 1739. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13111739 (2023).

Ponti, G. et al. The role of medium size facilities in the HPC ecosystem: the case of the new cresco4 cluster integrated in the ENEAGRID infrastructure. In 2014 International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation (HPCS), 1030–1033 (IEEE, 2014).

Acknowledgements

O.P. and I.K. acknowledge MUR for financial funding through the PRIN2020 PHOTO. F. B. acknowledges financial support from INFN Tor Vergata. Computing resources and the related technical support used for this work have been provided by CRESCO/ENEAGRID High Performance Computing infrastructure and its staff54, and by CINECA (ISCRA-B and ISCRA-C projects).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., O.P. and P.G.; methodology and theoretical modelling, I.K, P.G., O.P and F.B.; software, I.K. and P.G.; writing, editing and review I.K., P.G., O.P. and F.B.; supervision, F.B. and P.G.; project administration, O.P, P.G. and F.B.; funding acquisition, O.P. and P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kupchak, I., Bechstedt, F., Pulci, O. et al. Tuning the optical absorption and exciton bound states of germanene by chemical functionalization. Sci Rep 14, 25182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75620-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75620-w