Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of different pain mitigation methods during orthodontic debonding and to evaluate pain sensitivity across various regions of the dentition. A total of 144 participants (50 males and 94 females) with metal brackets were randomly assigned to one of four groups: High-Frequency Vibration (V), Cotton Roll (CR), Elastomeric Wafer (EW), and Open Mouth group (OM). Pain levels were measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) across different sextants of the dentition. The Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc analyses were conducted to compare VAS scores between groups. The Mann-Whitney test was used to analyse sex-based differences. The V group, utilizing high-frequency vibration, had the lowest total VAS score, indicating superior pain relief compared to CR, EW, and OM groups. No significant difference was observed between the CR and EW groups. Median VAS scores were highest in the lower front sextant, followed by the upper front sextants, and lowest in the posterior regions, indicating greater pain sensitivity in the anterior regions during debonding. High-frequency vibration was the most effective method for reducing pain during orthodontic debonding, particularly in the anterior dental regions. Both CR and EW methods were also effective but to a lesser extent. These findings suggest that high-frequency vibration could significantly improve patient comfort during orthodontic procedures. Utilizing high-frequency vibration for orthodontic debonding can enhance patient comfort, especially in the more sensitive anterior dental regions, thereby potentially improving treatment compliance and experience.

Trial registration: NCT05904587.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is a common issue across the different stages of orthodontic treatment. Procedures like placing separators, applying bands, inserting archwires, activating elastics, applying orthopaedic forces, performing rapid maxillary expansion, and conducting debonding procedures are usually associated with pain1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. This discomfort, which is inherently subjective, exhibits considerable variability among individuals and can be influenced by a variety of factors including age, sex, race, culture, individual pain thresholds, psychological factors, and the magnitude of applied force1,9,10,11,12,13. The debonding, an essential step in orthodontic treatment. The method used for debonding should ideally be painless, safe, and efficient14. Williams and Bishara (1992) proposed that applying an intrusive force, such as biting, during debonding could alleviate periodontal pain by stabilizing teeth and counteracting the forces on the periodontal ligament. This concept aligns with the gate control theory of pain1 which suggests that pain is not simply the result of linear neural processes from the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system. Instead, neural impulses signalling potential pain are modulated by a “gatelike” mechanism in the spinal cord’s dorsal horn before reaching the central nervous system. This theory posits that non-painful input can close the nerve “gates” to painful input, preventing pain signals from traveling to the central nervous system and that intrusive force acts on this gate mechanism15. When an intrusive force, such as finger pressure or biting on wafers, is applied during debonding, it stimulates the mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors in the periodontal ligament. This stimulation can activate large-diameter nerve fibers, which, according to the gate control theory, can inhibit the transmission of pain signals carried by smaller-diameter fibers. Furthermore, the additional pressure from the intrusive force may stabilize the teeth, counteracting the shear/peel and torsional forces applied to the periodontal ligament during debonding. This stabilization can reduce the perception of pain and discomfort associated with the procedure16.

Numerous modifications had been investigated to minimize pain and discomfort during debonding. These include the utilization of different orthodontic instruments, employing laser, administering analgesics, utilizing ultrasound or vibration, incorporating adjunctive procedures, applying thermal heating to orthodontic adhesives, and employing occlusal bite wafers16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Simple interventions like pressure application had been shown to manage pain whether from finger pressure1, or from biting on cotton rolls or elastomeric wafers12,13.

Low-frequency vibration (≤ 45 Hz) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain during orthodontic treatment23,24 and during the debonding procedure21, high-frequency vibration (≥ 90 Hz) remain unexplored in context of debonding pain reduction, despite their potential for reducing pain during different stages of orthodontic treatment25. They could also offer pain relief by stimulating mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors, which in turn modulate pain signals via the gate control theory of pain26. The lack of comprehensive research in this field underscores the need to investigate high-frequency vibration as a potential method for reducing pain during debonding, especially considering the scarcity of research in this specific area.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of high-frequency vibration in alleviating pain during debonding procedure, in comparison to biting on cotton rolls and elastomeric wafers as simple and effective pain management strategies. It will also examine the potential limitation of high-frequency vibration to provide a comprehensive understanding of the practicality and effectiveness of this method in real-world orthodontic practices.

Subjects and methods

Trial design

The study was a multi-centre, single-blinded, randomized clinical trial, with four-arm parallel groups and a matched allocation ratio.

Sample size

The difference between the various methods was considered to have a significant clinical impact when the difference on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is 15 mm22. Calculations based on prior studies revealed a standard deviation of 21.02 for the study group and 19.88 for the control group27. Subsequent power analysis indicated that to maintain a significance level (α) of 0.05 and achieve 80% power, each group would require a sample size of 30 subjects. To compensate for potential dropouts, 36 patients were enrolled in each group.

Eligibility criteria

This study included individuals aged 15 to 30 who demonstrated the ability to comprehend, assess, and respond to the questionnaires. Participants were undergoing orthodontic treatment involving both dental arches with 0.022-inch metal brackets and 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel final archwires, which had been in place for a minimum of two months.

Patients meeting any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: a history of recent or periodic medication intake within the past 24 h (such as analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, or anxiolytics); a Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) score of 8 or higher; presence of systemic diseases or condition known to influence pain perception; presence of debonded brackets at the time of debonding; missing teeth, except for extracted premolars; active periodontal conditions, including recession and mobility exceeding Grade I; heavily restored or root canal-treated teeth; craniofacial deformities impacting dentoalveolar bone quality (such as cleft lip and palate); history of surgical treatment, including impacted tooth removal; and the presence of miniscrews. Additionally, patients with an excessive amount of adhesive around brackets that could potentially interfere with the placement of the debonding pliers’ beaks were also excluded from the study.

Recruitment took place at the Department of Orthodontics, College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad teaching clinics, as well as three governmental specialized dental centres. Patients who had completed orthodontic treatment and met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the study. Participants were provided with an information sheet and consent was obtained from each participant prior to their recruitment in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations approved by the ethical committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad.

Randomization, concealment, and allocation

A straightforward non-stratified randomization approach was utilized via the online platform “randomization.com” in November 2022. The total numbers, ranging from 1 to 144 (corresponding to the suggested number of participants), was divided into four groups. Each group was then assigned a specific set of 36 randomly selected numbers within the range of 1 to 144.

In the allocation process, 144 small sealed envelopes were prepared, each containing a unique number from 1 to 144. Participants were instructed to randomly select one envelope, revealing the corresponding number inside, which determined their assigned group. Throughout this process, both the investigator and the participant remained unaware of the group assignment until the random number was drawn, ensuring unbiased group allocation.

As per the random selection process, patients were allocated into one of four groups:

Group A: Open Mouth Technique (OM) as the control group—The debonding procedure is performed with the patient’s mouth open, ensuring no contact between the treated arch teeth and the opposing arch teeth, and without finger support for the entirety of the procedure.

Group B: Cotton Roll (CR)—The debonding procedure involves the patient biting on a CR (Standard CR with a diameter of 1 cm and length of 3 cm were utilized, ensuring they were neither braided nor wrapped), applying a firm but not excessive bite force. The CR is replaced for each sextant of dentition to be debonded for maintaining consistency.

Group C: Elastomeric Wafer (EW)—A Soft 3 mm Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate (EVA) material EW (Ortho Technology, Tampa, Florida, United States), shaped into a horseshoe configuration using a preformed wax bite rim as a template, is placed on the occlusal surface of the lower teeth. The participant occludes on the sheet during debonding.

Group D: high-frequency Vibration (V)—The mouthpiece of the VPro device (SureSmile® VPro™, Dentsply Sirona Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina, United States) is positioned on the occlusal surface of the lower teeth, and the participant is instructed to bite on it firmly but not excessively. The debonding procedure is done while the device is active. A demonstration of the study groups is provided in Fig. 1.

Intervention

At enrolment, patients’ anxiety and fear of pain levels were assessed using the GAD-7, with a score below 8 indicating acceptable anxiety levels for study inclusion. Patients with scores of 8 and above, indicative of moderate to severe anxiety levels potentially impacting VAS scores, were excluded from the study. Pain intensity was evaluated immediately after debonding using a 100-mm VAS.

The VAS consisted of a millimetre ruler divided into five sections, each represented by images of a face ranging from happy to sad. A score of 0 indicated no pain, while 100 represented severe and intolerable pain (Appendix A). Before debonding, patients were briefed on the study objectives and informed that they would be required to assess pain intensity using the VAS in each sextant following the procedure: Upper Right (UR), Upper Anterior (UA), Upper Left (UL), Lower Right (LR), Lower Anterior (LA), and Lower Left (LL).

All debonding procedures were conducted by the same clinician (AIM) using the same Angled bracket removing pliers (International Orthodontics Services IOS, Inc, 12811 Capricorn St, Stafford, TX 77477, United States). This approach ensured consistency across the different centres involved in the study and eliminated variability in technique thus ensuring uniform application of the intervention protocols. The debonding process initiated from the upper and lower right sides of the jaws, respectively, with the archwires left in place. During debonding, the beaks of the debonding pliers were meticulously positioned at a right angle to the tooth surface and carefully aligned on the superior and inferior edges of the bracket base. Gentle pressure was applied to the upper and lower borders of the base, with a deliberate effort made to minimize any potential torsional force. To address potential recall bias, pain assessments were collected immediately after the procedure.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was only possible for the participant, who were unaware of the group assignments of other participants to prevent bias in pain perception reporting. Data analysis was also conducted in a blinded manner.

Data analysis

The obtained data were coded and transferred to an MS Excel spreadsheet. Subsequently, statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), with a confidence level set at 95% (p < 0.05) to assess significance. A per protocol analysis was followed. Descriptive analysis was conducted on the collected data. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using both the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, which indicated a non-normal distribution. To determine any statistically significant differences in the VAS pain scores across the oral cavity among the groups, and for intergroup comparisons, the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed. Additionally, the Mann–Whitney test was utilized to compare VAS scores between males and females. Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between GAD-7 and VAS scores. Categorical data analyses were performed using the Chi-square test. The VAS scores were presented as median values along with interquartile ranges.

Results

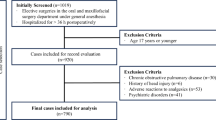

The study’s participants flow is outlined in a CONSORT diagram (Fig. 2). Initially, 157 participants were assessed and approached for inclusion. Ultimately, 144 participants were enrolled and completed the study. The distribution of participants by sex and age across different treatment arms is summarized in Table 1. the comparison of sex and age distribution among the groups did not reveal significant differences. Additionally, age did not show a significant impact, as indicated in Table 1.

A correlation test was conducted to examine the relationship between GAD-7 scores and VAS pain scores for the whole dentition. The results showed a very weak correlation (R = 0.024) and no statistical significance between GAD-7 and VAS scores. This suggests that, in this study, anxiety levels did not significantly influence pain perception during debonding.

The results of the sex-based Mann-Whitney Test indicated no statistically significant differences in VAS pain scores between females and males across the study arms. However, it is noteworthy that females had a higher median VAS score than males for the whole dentition (Table 2).

The differences in VAS scores were statistically significant across all areas of the oral cavity among all groups, as determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test (p < 0.0125), with the p-value adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests (Table 3). The median VAS score for the dentition was highest in the OM group (20 for the whole dentition) and lowest in the V group (8 for the whole dentition) (Table 3; Fig. 3). Across all groups, the highest median VAS scores were in the lower anterior sextants followed by the upper anterior sextants when compared to other sextants (Fig. 4). The findings are summarized in Table 3.

Pairwise comparisons conducted across the different sextant, entire arch, and whole dentition revealed a statistically significant difference between groups, with the p-value adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. The V group consistently exhibiting lower VAS scores as compared to all other test groups with narrow IQR. On the other hand, the OM group consistently demonstrated the highest VAS scores. Notably, there were no statistically significant differences between the CR and EW groups. These findings are summarized in Table 4; Fig. 4.

Discussion

A randomized clinical trial design was employed to assess the effectiveness of high-frequency vibration in reducing debonding pain compared to other methods. Additionally, the study explored the influence of sex and location of the dentition on pain perception.

This study utilized simple randomization with a random code generator and ensured allocation concealment to avoid selection bias and increase the generalizability of the study findings. To avoid performance bias and increase the objectivity, reliability, and credibility of the study, patient blinding was implemented. Participants were not informed about the potential effectiveness of any of the pain management methods used in the study. Instead, they were instructed to report their pain scores based solely on their subjective experience during the debonding procedure. This approach aimed to minimize any preconceived notions about the effectiveness of the methods, thereby that the pain scores accurately reflected the participants’ genuine pain experiences.

There was no attrition bias in this study, as there were no drop outs. consequently, the statistical power was increased to 86% and the ability to detect meaningful differences between groups was maintained. All outcomes were measured, analysed, and reported, which supports the conclusion that the study had a low risk of reporting bias.

The sex-based comparison of VAS scores using the Mann–Whitney U test revealed no significant differences. It is worth noting that, despite the lack of statistical significance, females reported higher pain scores across the entire dentition.

The GAD-7 questionnaire was selected for its simplicity and reliability in measuring anxiety levels, as endorsed by multiple scholars28,29,30. By utilizing the GAD-7 as a criterion for participant selection, the study aimed to identify individuals with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), a condition associated with heightened pain perception in previous research31,32. According to Spitzer et al. (2006), a GAD-7 score of 10 or higher indicates moderate anxiety, while scores from 5 to 9 suggest mild anxiety33. For this study, participants with scores of 7 or lower were recruited, specifically chosen from the lower half of the mild anxiety range to minimize potential confounding effects of elevated anxiety on pain perception. The impact of this criterion was reflected by having a very weak and non-significant correlation between GAD-7 scores and VAS scores for the whole dentition; in other words, the impact of anxiety on the measured pain scores was minimized.

VAS was selected due to its reduced susceptibility to individual beliefs or distress and its ability to provide a more comprehensive assessment of pain intensity compared to other scales34,35. It’s important to note that the potential variability in patient-reported outcomes due to the subjective nature of pain assessment cannot be entirely eliminated, even when using the VAS.

In this study, the angled bracket remover plier was specifically chosen for the debonding process because of its versatility in accessing both anterior and posterior regions of the dentition. This decision ensured consistency in instrument use throughout the study and is supported by its widespread acceptance and use for debonding orthodontic brackets in previous studies12,16,18,20,36. To minimize interoperator variability, a single operator (AIM) performed all debonding procedures using the same designated technique for all the study participants. The single-operator design, minimizes interoperator variability, but it introduces the risk of operator bias. The uniformity of the debonding technique across all participants is a strength, but it also means that any unconscious biases or variations in technique by the operator could have systematically influenced the results. To mitigate this risk, the study employed a sufficiently large sample size, which helps to reduce the impact of individual operator bias on the overall findings.

The influence of external factors, such as the environment in which the debonding procedures were performed, cannot be entirely ruled out. To address this, several measures were implemented to standardize conditions across all recruitment centres. Each establishment was equipped with a designated dental chair specifically for the study, and all debonding procedures were conducted between 9:00 and 11:00 p.m. to minimize the impact of circadian rhythms on pain perception. These steps were implemented to ensure a more consistent and accurate evaluation of the pain management methods.

Utilizing CR or similar materials to provide an intrusive force during debonding has been advocated in literature due to their effectiveness in addressing occlusal variations. Although Celebi et al. (2021) did explore the CR method13, direct comparisons with our study may not be entirely suitable due to differing methodologies. Their split-mouth design raises concerns about potential carry-over effects37. Hence, a more robust study design was chosen to assess the CR method potential for pain reduction.

Bavbek et al. (2016) found that finger pressure was more effective than EW in reducing debonding pain. Notably, this conclusion was reached after adjusting the VAS scores; before the adjustment, there was no significant difference between the pain control methods. This discrepancy could be attributed to the small sample size (21 participants per group), which may have limited the reliability of the initial results12. In contrast, Iqbal et al. (2023) reported that biting on an EW reduced debonding pain more effectively than finger pressure38. This discrepancy may stem from variations in the thickness of the wafer used, Iqbal et al. folded the wafer four times before employing it for biting and also included a larger sample size (55 participants per group) in their two-arm study. Therefore, there is a need to assess the effectiveness of EW and compare it to that of the CR, as both methods aim to alleviate debonding pain by applying simple intrusive force.

In orthodontics, vibration devices are categorized by frequency: low-frequency (≤ 45 Hz) and high-frequency (≥ 90 Hz). The AcceleDent device operates at a low-frequency, while the VPro device functions at high-frequency39. Vibration analgesia, as described by Hollins et al. (2014)40, involved using vibration to alleviate pain. As vibration was shown to reduce pain41. Casale and Hansson (2022) noted that high-frequency vibration align well with the gate control theory because it activates large-diameter A-β fibers, which are non-noxious mechanoreceptors and transmit impulses quickly due to their myelination. When these fibers are stimulated, they produce an inhibitory response that can close the “pain gate,” preventing pain signals from being sent to the brain. This results in a reduction of pain sensation26. In contrast, low-frequency vibration are less effective at stimulating A-β fibers and therefore do not have the same analgesic effect. In contrast, low-frequency vibration are more likely to increase motor output rather than modulate pain42.

Jayapal et al. (2020) found that low-frequency vibration from the AcceleDent device reduced debonding pain21. Conversely, high-frequency vibration has also been effective in pain reduction during orthodontic treatment, as concluded in the latest meta-analysis by Li et al. (2024)25. Given the documented efficacy of high-frequency vibration and the lack of research on its use for debonding pain, the VPro device was selected for this clinical trial.

Regardless of the method used, median VAS scores were highest in the lower anterior sextant, followed by the upper anterior sextants, and lowest in the upper and lower posterior regions. The increased VAS scores in the anterior region suggest that this area of the jaw is more sensitive to pain during debonding, a finding corroborated by previous studies2,18,43,44,45,46. The tactile sensory threshold of the anterior region is 1 g compared to 5 to 10 g in the posterior region of the dental arch16. This heightened sensitivity could be attributed to the anatomic location and root morphology of teeth in these regions. Teeth in the upper and lower anterior sextants typically have a single root with less surface area and are housed in a thinner cortical boundary, making them more susceptible to force during debonding compared to multirooted teeth in the posterior sextants, which are housed in a thicker cortical boundary2.

Notably, the VAS scores for the anterior region were the lowest when using the high-frequency vibration method compared to other methods. The V method showed a reduced VAS scores by 10–15 points as compared to other methods, which highlights its clinical significance22. Statistically significant differences in VAS scores were observed across various areas of the dentition among all groups. The intergroup comparison revealed that the V group had the lowest VAS scores compared to the other groups. It demonstrated a statistically significant difference in pain reduction in the anterior region as compared to the CR and OM methods. The V method had significantly lower VAS scores for the upper and lower dentition as well as the whole dentition. This suggests that the V method could be more effective for pain management than CR and EW methods.

Furthermore, significant differences in VAS scores were observed between the CR-OM group, and EW-OM group for the total dentition, indicating that these methods can be used to alleviate pain. However, there was no significant difference in VAS scores between the CR and EW groups, which suggests that they may be equally reliable in pain management during debonding.

The V method is a user-friendly and efficient approach to pain control. However, the requirement for specialized equipment may limit its availability in all orthodontic clinics. The CR and EW methods function by applying an intrusive force to the incisal or occlusal surface of the tooth. This could stabilize the tooth and mitigate the torsional and peeling forces exerted on the periodontal ligament during debonding. Additionally, these methods provide a proprioceptive stimulus that is thought to alleviate pain based on the gate control theory. Although the CR and EW methods were statistically equivalent in effectiveness, the CR method’s lower VAS score and its widespread availability could make it serve as a viable alternative to the V method.

Limitations

A potential limitation of the study is its focus on a specific ethnic population (Iraqi Arabs), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or clinical settings. Ethnicity has been shown to influence pain perception47,48, Additionally, variables such as bracket type (manufacturer) and adhesive type were not accounted for. These factors could potentially confound the study results, warranting caution when interpreting and extrapolating findings to broader populations or clinical contexts.

Conclusion

-

The High-frequency vibration emerges as a promising approach for pain management during debonding, potentially enhancing patient comfort and treatment experience. However, it requires the use of a specialized device which is not readily available for all practitioners.

-

Cotton rolls and elastic wafers are equally effective in alleviating pain during debonding, and both are less effective than the high-frequency vibration.

-

Despite the individual variation in pain reporting, and the anatomical variations, the anterior area of the dentition in both jaws tends to exhibit higher sensitivity to pain during debonding.

-

There is no difference in pain perception between different sexes.

Relevance to clinical practice and future research

The findings of the current study are significant for clinical orthodontic practice, suggesting that high-frequency vibration could offer a more effective and patient-friendly option for pain management during debonding. However, the need for broader validation studies must be considered. The effectiveness of high-frequency vibration in lowering debonding pain across diverse demographic groups, should be investigated considering variables such as age, sex, and ethnicity. This will aid in developing tailored pain management strategies.

Finally, designing a high-frequency vibrational device specifically for debonding procedures is needed. It should include a disposable or autoclave-safe mouthpiece to prevent contamination. The device should have a long, thin, strong, and sturdy connector to avoid interference during the debonding process. Such a device would enhance the practicality and efficacy of high-frequency vibration in clinical settings.

Data availability

The data will be available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Williams, O. L. & Bishara, S. E. Patient discomfort levels at the time of debonding: a pilot study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 101, 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-5406(05)80324-5 (1992).

Normando, T. S., Calçada, F. S., Ursi, W. J. S., Normando, D. Patients’ report of discomfort and pain during debonding of orthodontic brackets: a comparative study of two methods. World J. Orthod. 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21490985/ (2010).

Tuncer, Z., Ozsoy, F. S. & Polat-Ozsoy, O. Self-reported pain associated with the use of intermaxillary elastics compared to pain experienced after initial archwire placement. Angle Orthod. 81, 807–811. https://doi.org/10.2319/092110-550.1 (2011).

Panda, S., Verma, V., Sachan, A. & Singh, K. Perception of pain due to various orthodontic procedures. Quintessence Int. 46, 603–609. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a33933 (2015).

Baldini, A. et al. Influence of activation protocol on perceived pain during rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 85, 1015–1020. https://doi.org/10.2319/112114-833.1 (2015).

Saloom, H. F. Pain intensity and control with fixed orthodontic appliance therapy (a clinical comparative study on Iraqi sample). J. Bagh Coll. Dent. 24. https://www.iasj.net/iasj/article/70100 (2012).

Rafeeq, R. A., Saleem, A. I., Hassan, A. F. A. & Nahidh, M. Orthodontic pain (causes and current management) a review article. Int. Med. J. 25, 1071–1080 (2020). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340271678

Ahmed, O. K. & Kadhum, A. S. Effectiveness of laser-engineered copper-nickel titanium versus superelastic nickel-titanium aligning archwires: a randomized clinical trial. Korean J. Orthod. 54, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod23.081 (2024).

Ngan, P., Kess, B. & Wilson, S. Perception of discomfort by patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 96, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(89)90228-x (1989).

Summers, S. Evidence-based practice part 1: pain definitions, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and theories. J. Perianesth Nurs. 15, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpan.2000.18211 (2000).

Wandner, L. D., Scipio, C. D., Hirsh, A. T., Torres, C. A. & Robinson, M. E. The perception of pain in others: how gender, race, and age influence pain expectations. J. Pain. 13, 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.014 (2012).

Bavbek, N. C., Tuncer, B. B., Tortop, T. & Celik, B. Efficacy of different methods to reduce pain during debonding of orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 86, 917–924. https://doi.org/10.2319/020116-88R.1 (2016).

Celebi, F. Evaluation of the effects of cotton roll-biting on debonding pain: a split-mouth study. South. Eur. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Res. 8, 2–7. https://doi.org/10.5937/sejodr8-28046 (2021).

Pringle, A. M., Petrie, A., Cunningham, S. J. & McKnight, M. Prospective randomized clinical trial to compare pain levels associated with 2 orthodontic fixed bracket systems. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 136, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.08.032 (2009).

Melzack, R. & Wall, P. D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 150, 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3699.971 (1965).

Almuzian, M. et al. Effectiveness of different debonding techniques and adjunctive methods on pain and discomfort perception during debonding fixed orthodontic appliances: a systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 41, 486–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjz013 (2019).

Tsuruoka, T., Namura, Y. & Shimizu, N. Development of an easy-debonding orthodontic adhesive using thermal heating. Dent. Mater. J. 26, 78–83. https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.26.78 (2007).

Mangnall, L. A., Dietrich, T. & Scholey, J. M. A randomized controlled trial to assess the pain associated with the debond of orthodontic fixed appliances. J. Orthod. 40, 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1179/1465313313Y.0000000045 (2013).

Khan, H., Chaudhry, A. R., Ahmad, F., Warriach, F. Comparison of debonding time and pain between three different debonding techniques for stainless steel brackets. Pak. Oral Dent. J. 35 (2015).

Pithon, M. M., Santos Fonseca Figueiredo, D., Oliveira, D. D. & Coqueiro Rda, S. What is the best method for debonding metallic brackets from the patient’s perspective? Prog Orthod. 16, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-015-0088-7 (2015).

JananiJayapal, U. M. Comparison of pain perception during debonding between conventional and vibratory therapy. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 701–715. http://annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/9719 (2020).

Gupta, S. P., Rauniyar, S., Prasad, P. & Pradhan, P. M. S. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of different methods on pain management during orthodontic debonding. Prog Orthod. 23, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-022-00401-y (2022).

Aljabaa, A., Almoammar, K., Aldrees, A. & Huang, G. Effects of vibrational devices on orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 154, 768–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.07.012 (2018).

Ahmed, Z. S. H., Ahmed, N. S. H. & Ghaib, N. H. The effect of AcceleDent® device on both gingival health condition and levels of salivary interleukin-1-βeta and tumor necrosis factors-alpha in patients under fixed orthodontic treatment. J. Bagh Coll. Dent. 325, 1–8. https://jbcd.uobaghdad.edu.iq/index.php/jbcd/article/view/971 (2015).

Li, J. et al. The effect of physical interventions on pain control after orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 19, e0297783. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297783 (2024).

Casale, R. & Hansson, P. The analgesic effect of localized vibration: a systematic review. Part 1: the neurophysiological basis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 58, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.22.07415-9 (2022).

Bartlett, B. W., Firestone, A. R., Vig, K. W., Beck, F. M. & Marucha, P. T. The influence of a structured telephone call on orthodontic pain and anxiety. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 128, 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.033 (2005).

Johnson, S. U., Ulvenes, P. G., Oktedalen, T. & Hoffart, A. Psychometric properties of the General anxiety disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) scale in a Heterogeneous Psychiatric Sample. Front. Psychol. 10, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01713 (2019).

Dhira, T. A., Rahman, M. A., Sarker, A. R. & Mehareen, J. Validity and reliability of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among university students of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 16, e0261590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261590 (2021).

Pheh, K. S. et al. Factorial structure, reliability, and construct validity of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7): evidence from Malaysia. PLoS One. 18, e0285435. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285435 (2023).

Beesdo, K. et al. Association between generalized anxiety levels and pain in a community sample: evidence for diagnostic specificity. J. Anxiety Disord. 23, 684–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.007 (2009).

Fillingham, Y. A., Hanson, T. M., Leinweber, K. A., Lucas, A. P. & Jevsevar, D. S. Generalized anxiety disorder: a modifiable risk factor for pain catastrophizing after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 36, S179-S83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.02.023 (2021).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Thong, I. S. K., Jensen, M. P., Miro, J. & Tan, G. The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure? Scand. J. Pain. 18, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0012 (2018).

Bielewicz, J., Daniluk, B. & Kamieniak, P. VAS and NRS, same or different? Are visual Analog Scale values and Numerical Rating Scale equally viable tools for assessing patients after Microdiscectomy? Pain Res. Manag. 2022, 5337483. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5337483 (2022).

Nakada, N. et al. Pain and removal force associated with bracket debonding: a clinical study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 29, e20200879. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2020-0879 (2021).

Pandis, N., Walsh, T., Polychronopoulou, A., Katsaros, C. & Eliades, T. Split-mouth designs in orthodontics: an overview with applications to orthodontic clinical trials. Eur. J. Orthod. 35, 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjs108 (2013).

Iqbal, K., Khalid, Z., Khan, A. A. & Jan, A. Comparison of different methods of controlling pain during debonding of orthodontic brackets. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 73, 1408–1411. https://doi.org/10.47391/JPMA.6875 (2023).

García Vega, M. F. et al. Are mechanical vibrations an effective alternative to accelerate orthodontic tooth movement in humans? A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 11, 10699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112210699 (2021).

Hollins, M., McDermott, K. & Harper, D. How does vibration reduce pain? Perception. 43, 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1068/p7637 (2014).

Kakigi, R. & Shibasaki, H. Mechanisms of pain relief by vibration and movement. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 55, 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.55.4.282 (1992).

Bednáříková, H., Smékal, D., Krejčiříková, P. & Hanzlíková, I. Effect of locally applied vibration on pain reduction in patients with chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Acta Gymnica. 48, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.5507/ag.2018.010 (2018).

Firestone, A. R., Scheurer, P. A. & Burgin, W. B. Patients’ anticipation of pain and pain-related side effects, and their perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur. J. Orthod. 21, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/21.4.387 (1999).

Priya, A., Jain, R. K. & Santhosh Kumar, M. Efficacy of Different Methods to Reduce pain during Debonding of Orthodontic Brackets10 (Drug Invention Today, 2018).

Kilinc, D. D. & Sayar, G. Evaluation of pain perception during orthodontic debonding of metallic brackets with four different techniques. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 27, e20180003. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0003 (2019).

Karobari, M. I. et al. Comparative evaluation of different numerical pain scales used for pain estimation during debonding of orthodontic brackets. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 6625126. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6625126 (2021).

Krishnan, V. Orthodontic pain: from causes to management—a review. Eur. J. Orthod. 29, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjl081 (2007).

Krupic, F. et al. Ethnic differences in the perception of pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative research. Med. Glas (Zenica). 16, 108–114. https://doi.org/10.17392/966-19 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the clinicians in the Orthodontic Department at the College of Dentistry, as well as those at the governmental dental centres (Bab Al Muadham, Al Baladyat, and Al Chawadir). Their willingness to provide access to their patients was instrumental in enabling this research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S.K. Data curation: A.I.M. Formal analysis: A.S.K. Investigation: A.I.M. Methodology: A.S.K. Project administration: A.S.K. Resources: A.I.M. Visualization: A.I.M. Writing–original draft: A.I.M. Writing–review and editing: A.S.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The Ethics Committee of the College of Dentistry at the University of Baghdad granted approval for this study on February 19th, 2023, under identification number 780423.

Informed consent

All participants in the study were provided with an information sheet, and informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Musawi, A.I., Kadhum, A.S. Effectiveness of high-frequency vibration, cotton rolls and elastomeric wafers in alleviating debonding pain of orthodontic metal brackets: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 14, 25160 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75725-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75725-2