Abstract

In this study, MnFe2O4 microspheres were synthesized to activate potassium persulfate complex salt (Oxone) for the degradation of 17β-estradiol (17β-E2) in aqueous solutions. The characteristic of MnFe2O4 was detected by XRD, XPS and SEM-EDS. The experimental results indicated that the degradation of 17β-E2 followed pseudo-first-order kinetics. At 25 °C, 17β-E2 concentration of 0.5 mg/L, MnFe2O4 dosage of 100 mg/L, Oxone dosage of 0.5 mmol/L, and initial pH value of 6.5, the decomposition efficiency of 17β-E2 reached 82.9% after 30 min of reaction. Additionally, free radical quenching experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance analysis demonstrated that SO4−• and •OH participated in the reaction process of the whole reaction system, with SO4−• being the main reactive oxygen species (ROS). The activation mechanism of the MnFe2O4/Oxone/17β-E2 system is proposed as follows: MnFe2O4 initially reacts with O2 and H2O in solution to generate active Fe3+-OH and Mn2+-OH species. Subsequently, Fe3+-OH and Mn2+-OH react with Oxone in a heterogeneous phase activation process, producing highly reactive free radicals. After four cycles of MnFe2O4 material, the removal rate of 17β-E2 decreased by 24.1%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steroid hormones directly interact with the normal functioning of the endocrine system, thereby affecting reproduction and development in aquatic wildlife1, and have been widely found in different countries2,3,4. Estradiol (E2) can adversely affect reproduction and growth, the endocrine and nervous systems, and immune functions in both humans and animals even at very low concentrations (ng/L)5. Furthermore, estrogens can persist in treated wastewater after conventional sewage treatment processes, making it the primary source of estrogen contamination in aquatic environments6. Additionally, estrogens can even be reactivated during biological wastewater treatment through deconjugation7. Recent studies have demonstrated that 17β-E2 and estrone (E1, the main transformation products of 17β-E2) have relatively high detection frequencies and concentrations in major surface waters such as the Yangtze River and Pearl River in China8,9,10. Several physical, biological, and chemical methods can be used to control estrogen and testosterone pollution. The most common methods include photocatalytic degradation, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), adsorption, and biological degradation or biotransformation11. Among these methods, AOPs are the most common, successful, and economical method.

AOPs based on SO4−• have recently been used for the degradation of refractory organic pollutants12. The advantages of SO4−• include its strong oxidation potential (E° = 2.5–3.1 V)13, efficiency over a broad range of pH values (2–9)14, high solubility and stability15, and long half-life (30–40 µs)16. Persulfate (PS, S2O82−) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5−) are two commonly used oxidizing agents in AOPs, of which the latter is more easily activated due to its asymmetric structure. SO4−• can be produced by the activation of persulfate through various mechanisms, including the use of alkali, UV light, heat, ultrasound, transition metal, and carbon-based materials17,18. Among the various methods for activation of persulfates, non-homogeneous transition metal (Cu, Co, Fe, and Mn) activators have been widely used19. Single transition metal oxides suffer from low catalytic activity and leaching of metal ions; for this reason, activators such as the preparation of nano-oxides loaded on carriers, hetero-metallic doping for the preparation of bimetallic oxides, and composite transition metal oxide spinels such as XFe2O4 (X is a transition metal) have been investigated successively. Compared with metal oxide activators, the spinel-type activator XFe2O4 has the advantages of multiple active centers, high catalytic performance, and low leaching. Among them, spinel ferrite MnFe2O4 has excellent electron transfer rate, good biocompatibility, and excellent magnetic properties, which can be used to activate PMS for the treatment of difficult-to-degrade organic pollutants20,21,22.

Accordingly, the MnFe2O4/Oxone system was established to remove 17β-E2. This study explored the influencing factors of the MnFe2O4/Oxone reaction system for the removal of 17β-E2, the dominant reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the system and the degradation mechanism of 17β-E2, and finally, the recovery of MnFe2O4 were investigated.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

17β-estradiol (C18H24O2, HPLC pure), trisodium citrate (C16H5Na3O7), polyacrylamide ((C3H5NO) n, PAM), manganese chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2 ∙4H2O, A.R.), Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3∙6H2O, A.R.), potassium persulfate compound salt (2KHSO5∙KHSO4∙K2SO4, Oxone, A.R.), tert-butyl alcohol (C4H10O, superior grade) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co, Ltd. company. Absolute ethanol (C2H6O, A.R.), urea (CH4N2O, A.R.), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, A.R.), methanol (CH3OH, HPLC pure), acetonitrile (C2H3N, HPLC pure), hydrochloric acid (HCl, A.R.) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co, Ltd. All chemicals were purchased at least reagent grade and were used without further purification.

Preparation of MnFe2O4 microspheres

In this work, MnFe2O4 microspheres were prepared by hydrothermal synthesis, and the optimal preparation conditions were obtained after determining the E2 degradation rate under three factors, namely, the calcination temperature, calcination time, and heating rate (Fig. S1). First, manganese chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2∙4H2O) and ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3∙6H2O) at a molar ratio of 1:2 was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water and stirred by a magnetic stirrer. Then, 0.08 M trisodium citrate and 0.15 M urea were added. Finally, the solution was stirred continuously with the addition of 0.3 g of polyacrylamide (PAM) until completely dissolved. The obtained light-yellow liquid was poured into the stainless-steel reactor. After the reactor was sealed, it was put into a constant temperature drying oven at 200 °C for 12 h. The MnFe2O4 microsphere precursors were acquired after drying in a 50 °C oven. The dried MnFe2O4 microsphere precursor was put into a crucible and calcined in a muffle furnace at a heating rate of 10 °C/min to 200 °C. After calcination, the black powder was removed to obtain the MnFe2O4 microspheres. The influence of calcination temperature, time, and heating rate was systematically studied (Fig. S1a, b and c). The details of the experimental analyses are provided in Text S3.

Research methods for determining influencing factors

The 17β-E2 stock solution was diluted to the desired concentration with ultrapure water, 100 mL of 17β-E2 solutions with different initial concentrations were added, different pH values were adjusted with HCl and NaOH, and then specific dosages of activators and Oxone were added. The reactor was placed in a gas bath thermostatic shaker and shaken at 150 rpm for 17β-E2 degradation. Samples were taken at regular times. Isovolumetric methanol (100 µL) was added as a quenching agent. Then, the completely quenched samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm acetate membrane. The concentration of 17β-E2 was determined by HPLC, and all experiments were performed in three parallel experiments. The Kinetic fitting parameters at different pH values, temperatures, activator dosages, oxidant dosages and 17β-E2 concentration is shown in Table S1.

Analytical and characterization methods

The analytical methods are detailed in the Supporting Information (Text S1).

Results and discussion

Characterization of the MnFe2O4 activators

The surface morphology of the MnFe2O4 activators was characterized by SEM, as shown in Fig. 1a, b. The surface of the microspheres was covered by layers of MnFe2O4 particles with a tight and regular spherical structure and a uniform particle size between 100 and 200 nm. Only a few parts exhibit adhesion, with uniform dispersion and consistent particle integrity. The morphology and spatial structure of the MnFe2O4 activators were consistent with the SEM results. The color brightness in the middle of the MnFe2O4 microspheres is greater than that of their surroundings (Fig. 1(c, d)), indicating that the density around the spheres is greater than that inside23,24. In addition, the elemental mapping results illustrated the presence of elements such as oxygen (O), iron (Fe) (Fig. 1e and Fig. S2), manganese (Mn) and carbon (C) in the structure of MnFe2O4, and the elements of Fe and Mn were homogeneously distributed on the surface of MnFe2O4 with an Fe/Mn atomic ratio of 2.27/1, which was close to the atomic ratio in the experimental design value (2:1) (Fig. 1f).

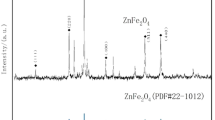

The XRD pattern reveals the crystal phase and crystallinity of the synthesized hollow MnFe2O4 microspheres. As shown in Fig. 2a, the diffraction peaks corresponding to the cubic spinel structure of MnFe2O4 align with the standard reference file (JCPDS 10-0319) obtained from MDI Jade 625. In the 2θ range of 10° to 80°, the diffraction peaks of the hollow microspheres are observed at 2θ = 18.027°, 29.834°, 35.011°, 42.579°, 56.810°, and 62.424°. The absence of any additional peaks indicates that the synthesized sample possesses a single-phase cubic spinel structure. However, the XRD spectrum indicates a relatively low crystallinity, which may be attributed to the lower calcination temperature or smaller particle size during the synthesis process.

The recovery of the activators under a magnetic field was examined by testing the magnetic strength of the MnFe2O4 microspheres, and the results are shown in Fig. 2b. The hysteresis lines of the prepared samples exhibit narrow hysteresis lines characteristic of soft ferromagnetic materials at room temperature from − 20 kOe to + 20 kOe applied magnetic field, indicating that less energy is required to be consumed in the process of reversal magnetization26. The MnFe2O4 microspheres exhibited a saturation magnetization intensity of 29.037 emu/g, indicating their magnetic properties.

Influence of parameters on 17β-E2 degradation by the MnFe2O4/oxone system

Effects of initial pH and reaction temperature

The initial pH is commonly considered one of the most important impacts during the Fenton or Fenton-like oxidation process27. Fenton chemistry and PS activation both generate reactive radicals for pollutant degradation. In systems utilizing Fe2+, Fenton chemistry produces •OH, while PS activation generates SO4−•, with Fe2+ serving as a activator for both processes28,29. Figure 3a indicates that the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 under acidic and neutral conditions was significantly greater than that under alkaline conditions. The degradation efficiencies at pH 3, 5, and 7 were 73.1%, 70.6%, and 76.7%, respectively, demonstrating its catalytic activity across different pH levels. However, the degradation efficiency decreased to 57.7% at pH 9. This may be because hydroxide ions (OH-) in the solution react with the activators surface to hydrolyze and generate hydroxide precipitates under alkaline conditions. Fewer protons remained at the active sites on the edges of MnFe2O4, which hindered Oxone activation and consequently reduced the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2. Similarly, Hu reported similar experimental results for an oxide system composed of cobalt oxides30. It was found that a broad pH range showed some buffering ability for the degradation of contaminants, and all 17β-E2 could be eliminated within 15 min when the initial solution pH varied from 3.0 to 9.0.

As shown in Fig. 3b, the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 were 64.8%, 74.9%, and 86.3% as the temperature increased from 25 °C to 45 °C within 30 min. The degradation efficiency increased with increasing reaction temperature. This is mainly because the energy absorbed by the reaction system increases with increasing temperature, which is conducive to the transfer of electrons from the activators to Oxone31,32. High temperature is beneficial for the decomposition of PMS into free radicals18. In addition, a higher reaction temperature promotes thermal movement between molecules and accelerates the frequency of collisions between PMS, 17β-E2, and MnFe2O4, thereby accelerating the reaction.

Effects of activators dose, oxidant dose, and initial 17β-E2 concentration

As shown in Fig. 3c, the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 increased as the amount of MnFe2O4 gradually increased. When the concentration of MnFe2O4 increased from 50 mg/L to 500 mg/L, the degradation efficiency increased by 44.9%. With increasing activators dosage in solution, more catalytic active sites were available for the activation of Oxone to produce more SO4−• radicals; therefore, the degradation efficiency and reaction rate of 17β-E2 increased. Compared to previous similar studies33,34, this system achieved a higher removal rate of 17β-E2 with a lower amount of activator, demonstrating the superior catalytic activity of the material prepared in this study.

The effect of different initial Oxone concentrations on 17β-E2 degradation was also investigated. As shown in Fig. 3d. When the concentration of 0.1 mM Oxone was increased to 1.0 mM, the 17β-E2 degradation efficiency increased from 49.3 to 85.4%. A low concentration of oxidant in the solution was activated rapidly to participate in the reaction under the condition of a fixed activators dosage. When the dosage of oxidant further increased, the catalytic reaction rate reached a maximum, and the continuous catalytic production of SO4−• participated in the reaction. These results are consistent with the findings reported in previous studies18,35. These results obviously indicated that MnFe2O4/Oxone system could operate efficient at less Oxone concentrations, which was superior to some reported advanced oxidation systems36,37,38.

As shown in Fig. 3e, when the initial concentration of 17β-E2 increased from 0.5 mg/L to 5.0 mg/L, the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 decreased from 82.9 to 28.2%, and the reaction rate decreased from 0.0542 min−1 to 0.0110 min−1, indicating that the degradation rate of the reaction system gradually decreased as the pollutant concentration gradually increased. The greater the concentration of pollutants in the system is, the fewer active contact sites there are between the activators and the oxidant, thus slowing the reaction rate. In addition, the degradation intermediates increased as the concentration of 17β-E2 increased, indicating a competitive relationship among pollutants, intermediate products, and ROS. The interaction probability between 17β-E2 and ROS was further reduced, leading to a decrease in the degradation efficiency and reaction rate. Nonetheless, within 30 min degradation period, the total amount of 17β-E2 degraded increased from 0.41 mg/L to 1.41 mg/L as the concentration of the pollutant increased, which also indicated that pollutants at high concentrations were more likely to participate in the reaction process and that the total degradation of pollutants increased. Notably, the high concentration state was beyond the tolerance range of the system, resulting in a low overall degradation efficiency and reaction rate39.

Reaction mechanisms

Reactive oxygen species analysis

According to a previous study, PMS activation leads to •OH and SO4−• radicals40. Two scavengers (i.e., methanol (MeOH) and tert-butanol (TBA)) were selected to investigate the dominant ROS in the MnFe2O4 microsphere-activated Oxone system. TBA can rapidly quench •OH (kTBA, SO4•− = 4.0 × 105 M− 1·s− 1; kTBA, •OH = 6 × 108 M− 1·s− 1) with a lower reaction rate constant on SO4−•35. The addition of excess TBA (500 mM) is commonly used to assess the contribution of •OH to pollutant degradation in the MnFe2O4/Oxone activation system. As shown in Fig. 4a, the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 decreased from 77.6 to 60.4% within 30 min in the presence of TBA. TBA slightly inhibited the 17β-E2 degradation process, indicating that •OH played a minor role in the MnFe2O4/Oxone activation system. MeOH was further employed as a quencher to assess the role of SO4−• (kMeOH, SO4−• = 3.2 × 106 M− 1·s− 1; kMeOH, •OH = 9.7 × 108 M− 1·s− 1)41. As displayed in Figs. 4a and 17β-E2 degradation efficiency decreased significantly from 77.6 to 17.9% after the addition of MeOH, demonstrating that SO4−• was the main ROS during the 17β-E2 degradation process. Adding MeOH to quench •OH or SO4−• radicals reduced the reaction rate from 0.048 min− 1 to 0.006 min− 1. Adding TBA to quench •OH reduced the rate to 0.03 min− 1, indicating that SO4−• reacts with 17β-E2 faster. Therefore, TBA’s effect on SO4−•-mediated 17β-E2 degradation is likely limited. The quenching experimental results showed that both SO4−• and •OH contributed to the degradation of 17β-E2 in the MnFe2O4/Oxone system.

The direct identification of SO4−• and •OH by EPR was performed with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as the main spin trap. As shown in Fig. 4b, the mixture of DMPO with the MnFe2O4/Oxone system exhibited distinct specific 4-fold peaks with an intensity ratio of 1:2:2:1, which can be identified as the detection signal of the DMPO-•OH adduct. In addition, the signals of DMPO-SO4−•− adducts were also present in the MnFe2O4/Oxone system, i.e., specific 6-fold peaks at a 1:1:1:1:1:1 ratio. A very weak intensity of the SO4−• spectral peak can be found, which is attributed to the rapid conversion of DMPO-SO4−• to DMPO-•OH42,43,44.

Possible activation mechanism

XPS analysis of the surface properties of MnFe2O4 before and after the reaction was used to elucidate the changes in chemical valence. The XPS spectra before and after the reaction of MnFe2O4 are shown in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5a, the measured spectra demonstrate the presence of four elements, Mn, Fe, O, and C, in MnFe2O4. The peaks at 711.2 eV and 724.6 eV are assigned to Fe 2p 3/2 and Fe 2p 1/2, respectively, indicating the presence of only Fe3+ in MnFe2O4 before use37. The peaks at 642.4 eV and 653.6 eV are assigned to Mn 2p 3/2 and Mn 2p 1/2, respectively, which indicates that only Mn2+ is present on the sample surface33. The XPS analysis results are consistent with the binding energy of spinel-type MnFe2O4 reported in the prior literature22. After the degradation experiment, the binding energy is slightly shifted, the peak area is reduced, and the Mn and Fe species on the activators surface are present in mixed valence states. The deconvolution of the Fe 2p 3/2 and Mn 2p 3/2 peaks of the activators indicates that the multivalent states of Fe2+/Fe3+ and Mn2+/Mn3+ coexist on the surface. After the catalytic reaction, the percentages were 56.0% and 44.0% for Fe2+/Fe3+ and 52.9% and 47.1% for Mn2+/Mn3+, respectively. The Fe 2p 3/2 and Mn 2p 3/2 peak areas demonstrated reactions involving Mn2+-Mn3+-Mn2+ and Fe3+-Fe2+-Fe3+ in catalytic oxidation, respectively. Figure 5d shows that two peaks are located at 529.7 eV and 531.1 eV from the lattice oxygen Olatt and adsorbed oxygen Oads in the O1s region, respectively45. Compared to Olatt, Oads has greater mobility and can actively participate in multiphase catalytic oxidation. The proportion of Oads increased from 42.8 to 47.7% after the reaction, demonstrating that an increase in the content of Oads can lead to an increase in catalytic activity.

Based on the quench experiment and XPS analysis, the proposed activation mechanism is shown in Fig. 6. In the MnFe2O4/Oxone/17β-E2 reaction system, H2O molecules are physically adsorbed on the MnFe2O4 surface and combine with the metal cations Fe3+ and Mn2+ to form Fe3+-OH and Mn2+-OH. When oxygen is dissolved in the system, SO4−• and SO4-OH can be generated instantaneously, as shown in Eqs. 1, 2, and 346, thereby oxidizing and decomposing 17β-E2 to CO2 and H2O (Eq. 4). Moreover, the reduction of the high-valent metal Mn3+ can result in the formation of SO5−•, which contributes less to 17β-E2 degradation (Eq. 5), and Fe2+ can also induce the generation of ROS in combination with surface ROS (Eq. 6). Subsequently, the reaction between the formed Fe3+ species and Oxone generates more Fe2+ and reactive radicals, and the cyclic reaction between Fe2+/Fe3+ and Mn2+/Mn3+ facilitates the direct activation of PMS47. Reversible oxidation and reduction maintain the structure of MnFe2O4, and the activation of Oxone results in high performance.

Degradation pathways of the MnFe2O4/oxone system

To understand the degradation process of 17β-E2 in the MnFe2O4/Oxone process, LC‒MS was used to analyze the products and pathways of 17β-E2 degradation. The degradation reaction conditions of High Resolution Liquid Mass Spectrometer with Orbital Trap (LC-MS) is shown in Text S2. As shown in Fig. 7, three potential degradation pathways for 17β-E2 were proposed based on the detection of nine intermediate products. The main degradation pathway of 17β-E2 is the substitution, breakage, and ring opening of the ring group of the benzene ring. The C2 and C4 rings of E2 had the highest Fukui index values compared to those of the other positions48. Consequently, they were more susceptible to loss of electrons and substitution by strong electron-withdrawing groups, such as •OH and SO4−•49. In path I, 17β-E2 was converted to E1 (P1), and the free radical preferentially attacked the C-position to form P4 (MW 286), with the hydroxyl substituent reacting to form P5 (MW 290). After phenyl ring hydroxyl substitution, the phenomenon of π-electron cloud polarization was intensified, triggering benzene ring breakage and hydroxyl substitution and producing P6 (MW 304). In path II and path III, the radicals chose to attack the benzene ring first, producing P2 and P3 (MW 256 and MW 274), forcing the molecular polarization of the benzene ring π-electron cloud and the conjugation phenomenon, which led to ring opening (MW 308). Meanwhile, the electron cloud was rearranged, the conjugation system was eliminated, and the benzene ring transformed into a chain structure with C-C single bonds or C-C double bonds. Compared to the ring structure, the chain structure is less stable and more vulnerable to attack and delocalization (MW 294, MW280). The possible degradation pathway of E2 involves the loss of electrons from the benzene ring (aromatic ring), hydroxyl substitution, ring opening, and dehydroxylation.

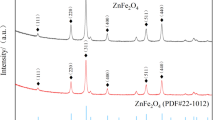

Stability and recyclability of MnFe2O4 microspheres

The stability of the MnFe2O4 microspheres during the 17β-E2 degradation process was investigated under optimal reaction conditions. Figure 8a compares the XRD patterns of the activators before and after the test, and the results of the recycling experiments show that the XRD pattern is still consistent with that of the original MnFe2O4; no spurious peaks and no significant changes were observed in the positions of the characteristic peaks after 1, 3, and 5 reuse cycles, further demonstrating the stability of the MnFe2O4 activators. The high stability of the activators can be attributed to its stable spinel structure50. As shown in Fig. 8b, the degradation efficiency of the activators for 17β-E2 was still greater than 50.0% within 30 min after five consecutive cycles. The overall decrease of 24.1% in the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2 could be attributed to the agglomeration of the activators after five reuses and the occupation of the activators active site by the remaining 17β-E2 or intermediates. As shown in Fig. 8c, although the leached amount of Mn is greater than that of Fe, the proportion of Fe in the MnFe2O4 structure is twice that of Mn. After the first catalysis, the highest leached amounts of Fe and Mn were 303.84 µg/L and 386.24 µg/L, respectively, but the leaching rate was only 0.1%. These results indicate that the activators can remain stable and retain sufficient sites throughout the recycling process. The experimental results show that MnFe2O4, which is highly reusable and recyclable, can be reused more than five times while maintaining over 50% of its initial catalytic efficiency and consistent activation capability, which can significantly reduce the operating cost in practical applications.

Conclusion

In the present study, prepared MnFe2O4 microspheres with consistent structural integrity and a magnetic recovery rate, were applied to activate Oxone to effectively degrade 17β-E2. The MnFe2O4/Oxone catalytic degradation system has a wide range of applications, and both the MnFe2O4 dosage and the Oxone concentration can influence the degradation efficiency of 17β-E2. At 25 °C, 17β-E2 concentration of 0.5 mg/L, MnFe2O4 dosage of 100 mg/L, Oxone dosage of 0.5 mM, and initial pH value of 6.5, the removal efficiency of 17β-E2 reached 82.9% after 30 min of reaction.

The quenching experiments showed that SO4−•- and •OH were the main ROS in the MnFe2O4/Oxone activation system and that SO4−•- was dominant for the degradation of 17β-E2. The XPS characterization results indicated that both metal ions on the activators surface participated in the reaction process. According to the newly generated Fe2+ and Mn3+, the cyclic reaction between Fe2+/Fe3+ and Mn2+/Mn3+ was a Fenton-like reaction.

Through recycling experiments, it was demonstrated that the MnFe2O4 microspheres retained structural stability, with a degradation efficiency of over 50% for 17β-E2 after five consecutive cycles. The recycling experimental results proved that the MnFe2O4/Oxone degradation system has potential practical prospects for 17β-E2 elimination in aquatic environments.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kumar, A. K., Reddy, M. V., Chandrasekhar, K., Srikanth, S. & Mohan, S. V. Endocrine disruptive estrogens role in electron transfer: bioelectrochemical remediation with microbial mediated electrogenesis. Bioresour. Technol. 104, 547–556 (2012).

Praveena, S. M., Lui, T. S., Hamin, N. A., Razak, S. Q. N. A. & Aris, A. Z. Occurrence of selected estrogenic compounds and estrogenic activity in surface water and sediment of Langat River (Malaysia). Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 1 (2016).

Pu, H., Huang, Z., Sun, D. W. & Fu, H. Recent advances in the detection of 17beta-estradiol in food matrices. Rev. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, 2144–2157 (2019).

Valdes, M. E. et al. Screening Concentration of E1, E2 and EE2 in Sewage Effluentsand Surface Waters of the Pampas Region and the Río de la Plata (2015).

Liu, N. N., Zhao, X. & Tan, J. C. Mycobiome dysbiosis in women with intrauterine adhesions. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, 0132422 (2022).

Ting, Y. F. & Praveena, S. M. Sources, mechanisms, and fate of steroid estrogens in wastewater treatment plants: a mini review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 1–19 (2017).

Bilal, M. et al. Iqbal Robust strategies to eliminate endocrine disruptive estrogens in water resources. Environ. Pollut. 306, 119373 (2022).

Shi, B. Y., Wang, Z. Y. & Liu, J. J. Pollution characteristics of three estrogens in drinking water sources in Jiangsu reach of the Yangtze River. Acta Sci. Circumst. 38, 857–883 (2018).

Chao, S., Yan, C. & Di, L. Endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the aquatic environment of China: which chemicals are the prioritized ones? Sci. Total Environ. 720, 1 (2020).

Ruijie, T., Ruixia, L. & Bin, L. Typical endocrine disrupting compounds in rivers of northeast China: occurrence, partitioning, and risk assessment. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 75, 213–223 (2018).

Zhang, C., Li, Y., Wang, C., Niu, L. & Cai, W. Occurrence of endocrine disrupting compounds in the aqueous environment and their bacterial degradation: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1–59 (2015).

Ma, Z. et al. Enhanced degradation of 2,4-dinitrotoluene in groundwater by persulfate activated using iron carbon microelectrolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 311, 183–190 (2017).

Senem, Y. G., Can-Güven, E. & Yıldız, G. V. Persulfate enhanced electrocoagulation of paint production industry wastewater: process optimization, energy consumption, and sludge analysis. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 157, 68–80 (2022).

Zhao, J., Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, B. & Yin, M. Environmental technology & innovation heterogeneous activation of persulfate by activated carbon supported iron for efficient Amoxicillin degradation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 21, 101259 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Application of sulfate radicals-based advanced oxidation technology in degradation of trace organic contaminants (TrOCs): recent advances and prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 308, 114664 (2022).

Mozaffariana, S. Y. M. M. & Ramezani, B. D. S. F. COD and ammonia removal from landfill leachate by UV/PMS/Fe2 + process: ANN/RSM modeling and optimization. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 159, 716–726 (2022).

Ao, X. et al. Mechanisms and toxicity evaluation of the degradation of sulfamethoxazole by MPUV/PMS process. Chemosphere 212, 365–375 (2018).

Fu, H., Ma, S., Zhao, P., Xu, S. & Zhan, S. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by graphitized hierarchical porous biochar and MnFe2O4 magnetic nanoarchitecture for organic pollutants degradation: structure dependence and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 360, 157–170 (2019).

Li, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, H., Tong, X. & Feng, J. Fabrication of sewage sludge-derived magnetic nanocomposites as heterogeneous catalyst for persulfate activation of Orange G degradation. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 529, 856–863 (2017).

Ye, P. et al. Coating magnetic CuFe2O4 nanoparticles with OMS-2 for enhanced degradation of organic pollutants via peroxymonosulfate activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 428, 131–139 (2018).

Oxidation of Bisphenol A by Persulfate via Fe3O4-α-MnO2 Nanoflower-Like Catalyst: Mechanism and Efficiency. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1385894718318904

Yao, Y. et al. Magnetic recoverable MnFe2O4 and MnFe2O4-graphene hybrid as heterogeneous catalysts of peroxymonosulfate activation for efficient degradation of aqueous organic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 270, 61–70 (2014).

Jin, C. et al. Functionalized hollow MnFe2 O4 nanospheres: design, applications and mechanism for efficient adsorption of heavy metal ions. New J. Chem. 43, 5879–5889 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Solvothermal synthesis of MnFe 2 O 4 colloidal nanocrystal assemblies and their magnetic and electrocatalytic properties. New J. Chem. 39, 361–368 (2015).

Wang, L., Li, J., Wang, Y., Zhao, L. & Jiang, Q. Adsorption capability for Congo red on nanocrystalline MFe2O4 (M = Mn, Fe Co, Ni) spinel ferrites. Chem. Eng. J. 181–182, 72–79 (2012).

Chamé, K. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles (2013).

Zhou, L. et al. Ferrous-activated persulfate oxidation of arsenic(III) and diuron in aquatic system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2632, 422–430 (2013).

Yu, D. et al. The remediation of organic pollution in soil by persulfate. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 235, 689 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. The practical application and electron transfer mechanism of SR-Fenton activation by FeOCl. Res. Chem. Intermed. 47, 795–811 (2021).

Hu, L., Liu, M. & S, Z. G. & Enhanced degradation of bisphenol A (BPA) by peroxymonosulfate with Co3O4-Bi2O3 catalyst activation: effects of pH, inorganic anions, and water matrix. Chem. Eng. J. 338, 300–310 (2018).

Jortner, J. Temperature dependent activation energy for electron transfer between biological molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 64, 4860–4867 (1976).

Wang, H. et al. The electronic structure of transition metal oxides for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 19465–19488 (2021).

Wang, J., He, Z., Wang, Y. & Lu, M. Electrochemical/peroxymonosulfate/nrgo-MnFe2O4 for advanced treatment of landfill leachate nanofiltration concentrate. Water 13, 413 (2021).

Yao, B. et al. p-Arsanilic acid decontamination over a wide pH range using biochar-supported manganese ferrite material as an effective persulfate catalyst: performances and mechanisms. Biochar 4, 31 (2022).

Xu, Y., Ai, J. & Zhang, H. The mechanism of degradation of bisphenol A using the magnetically separable CuFe2O4/peroxymonosulfate heterogeneous oxidation process. J. Hazard. Mater. 309, 87–96 (2016).

Hu, Z. et al. Development of natural attapulgite derived ferromanganese spinel oxides as heterogeneous catalysts for persulfate activation of tetracycline degradation. Chemosphere 352, 141428 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Efficient degradation of thiamethoxam pesticide in water by iron and manganese oxide composite biochar activated persulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 473 (2023).

Cao, Y., Jin, Y., Zhou, Z., Tian, S. & Ren, Z. Magnetic catalysts of MnFe2O4-AC activated peroxydisulfate for high-efficient treatment of norfloxacin wastewater. Chem. Phys. Lett. 840, 141159 (2024).

S, K., D, G. & S, B. & Degradation of 17α-ethinylestradiol by nano zero valent iron under different pH and dissolved oxygen levels. Water Res. 125, 32–41 (2017).

Nie, M. et al. Degradation of chloramphenicol by thermally activated persulfate in aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 246, 1 (2014).

X, W. S., Q, L. Y. & B, W. H. & Effective degradation of sulfamethoxazole with Fe2+-zeolite/peracetic acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 233, 115973 (2020).

Peng, H. et al. Fe3O4-supported N-doped carbon channels in wood carbon form etching and carbonization: boosting performance for persulfate activating. Chem. Eng. J. 457, 141317 (2023).

Su, W., Li, Y., Hong, X., Lin, K. A. & Tong, S. Catalytic ozonation of N,N-dimethylacetamide in aqueous solution by FegO4@SiO2@Mg0 composite: optimization, degradation pathways and mechanism. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 135, 104380 (2022).

Meng, X. et al. Activation of peroxydisulfate by magnetically separable rGO/MnFe2O4 toward oxidation of tetracycline: efficiency, mechanism and degradation pathways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 282, 120137 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. Heterogeneous activation of peroxymonosulfate using ordered mesoporous Co3O4 for the degradation of chloraphenicol at neutral pH. Chem. Eng. J. 308, 505–515 (2017).

Tan, C., Gao, N. & Fu, D. Efficient degradation of Paracetamol with nanoscaled magnetic CoFe2O4 and MnFe2O4 as a heterogeneous catalyst of peroxy monosulfate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 175, 47–57 (2017).

Hao, H. et al. Insight into the degradation of Orange G by persulfate activated with biochar modified by iron and manganese oxides: synergism between Fe and Mn. J. Water Process. Eng. 37, 101470 (2020).

Yang, S., Yu, W. & Du, B. A citrate-loaded nanozero-valent iron heterogeneous Fenton system for steroid estrogens degradation under different acidity levels: the effects and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129967 (2021).

Chen, Y., Kang, J. & Li, Z. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by Co2P via interfacial radical pathway for the degradation and mineralization of carbamazepine. Surf. Interfaces 1, 103045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103045 (2023).

Ren, Y., Dong, Q. & Feng, J. Magnetic porous ferrospinel NiFe2O4: a novel ozonation catalyst with strong catalytic property for degradation of di-n-butyl phthalate and convenient separation from water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 382, 90–96 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 51608079, the Chongqing Basic and Frontier Research Project, No. cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0176, and the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202404306). This work was supported by the Chongqing Graduate Joint Training Base Construction Project (Grant No. JDLHPYJD2022005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WY and TA conceptualized and executed the study and authored the manuscript; their contributions to the manuscript are equal. WS, SY, JT, QJ and CY engaged in data analysis and manuscript revision. WY, YM, FY, CY and SC reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, W., Ai, T., Sun, W. et al. Efficient removal of estradiol using MnFe2O4 microsphere and potassium persulfate complex salt. Sci Rep 14, 29329 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75781-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75781-8