Abstract

The emotional valence of animals is challenging to assess, despite being a key component of welfare. In this study, we attempted to assess emotional valence through memory in 1- and 3-week-old piglets. It was hypothesized that piglets would spend less time in a pen where they experienced a negative event (castration) and more time in a pen where they experienced a positive event (enrichment). A testing apparatus was designed with three equally sized pens: two outer sections serving as treatment pens containing unique visual and tactile cues and a center section remaining neutral. Piglets received either negative or positive condition in one outer treatment pen and a sham treatment in the opposite. Various methods were tested (age of piglets, number and length of conditioning sessions, passive vs. active conditioning). Contrary to expectations, piglets did not decrease their time in the pen associated with the negative condition or increase their time in the pen associated with the positive condition. However, when exposed to the positive condition, results indicate older piglets developed an aversion towards the sham treatment. This study provides methodological groundwork for the application of place conditioning in piglets and highlights the nuances important for the use of cognitive tests to assess animal welfare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animals’ ability to experience affective states1 are a key component of their welfare2. Affective states are argued to be structured around two main components: arousal (i.e. level of activation) and valence (positive or negative)3.

Measuring emotions in animals is challenging4, but the affective valence of an experience can be assessed through the memories it creates. Place conditioning paradigms allow for estimation of the valence that an animal assigns to an experience by associating an environment with a stimulus. The animal is then tested to see if the environment is approached (positive association) or avoided (negative association) in the absence of the stimulus5. Place conditioning has been widely used in rodent research to study the rewarding or aversive properties of stimuli such as food6, social partners7 or drug treatments8.

Although less common in swine research, place conditioning has been applied to study pigs’ preferences and avoidances. Pigs spent more time in a compartment where they previously had to search through straw for treats in comparison to a compartment where ‘free’ treats were available9. Pigs were more likely to turn around and took longer to move when they expected a negative situation (crossing a partially black ramp) in comparison to a positive one (popcorn treat)10, and they quickly learned to avoid an electric shock cued by an acoustic signal11,12.

To our knowledge, place conditioning has not been used to study the affective states of young piglets. We selected two interventions likely to induce changes in affective valence: castration for negative affect, and enrichment for positive affect.

Castration was chosen as a model of a negative experience as several lines of evidence suggest the procedure to be painful. To mention a few, castration induces increases in number of pain-related behaviours13,14, vocalisations15,16, cortisol levels17,18, pressure sensitivity19, blood pressure and heart rate20.

On the other hand, environmental enrichment was selected as a model of positive intervention as previous studies report pigs showing interest for enrichment such as straw21,22, ropes23 and sucrose solution24,25. Providing enrichment was also noted to increase play and exploratory behaviours26,27,28, reduce aggression28,29, tail-bites30, and improve average daily gains31.

We hypothesize that piglets will have a longer latency to enter and spend less time in an environment associated with castration (i.e. develop a conditioned aversion). Conversely, piglets will have a shorter latency and spend more time in an environment associated with enrichment (i.e. develop a conditioned preference). This study is exploratory and will investigate several methodologies, varying age of the subjects, number and length of conditioning sessions, as well as type of conditioning used.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study took place between June 2022 and July 2023 at the University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine’s Swine Teaching & Research Center in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania (USA). Castration treatments followed routine practice under Global Animal Partnership’s Animal Welfare standards32, the study was approved under the University of Pennsylvania IACUC protocol 804656 and reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Animals

We enrolled a total of 110 boar piglets (Genesus Jersey Red Duroc x Topigs Norsvin TN70), divided among 5 trials (n = 22 piglets per trial). This number was based on de Jonge and colleagues9, who enrolled between 12 and 21 piglets for a place conditioning paradigm. Based on farrowing schedule, piglets were pseudo-randomly selected (first ones caught, healthy) from 24 litters (4.8 ± 1.1 per trial). All piglets acted as their own control and received both treatment and sham procedures (see next sections for treatment details). Experimental piglets were housed from birth with the rest of their litter in a 2.1 × 2.0 m farrowing pen with their dam. Pen flooring was perforated plastic with an embedded 0.6 × 0.6 m heating pad continuously available to the piglets.

Piglets had ad libitum access to solid feed (PO20PS Kalmbach organic pig starter, Pennsylvania, USA) and water. As part of routine farm procedure, room temperature was kept at approximately 20 °C.

Apparatus

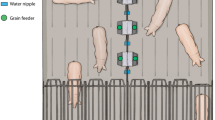

The place conditioning apparatus was a 2.5 m x 0.9 m x 1.0 m box (Fig. 1) made of plastic partitions divided in three equal areas (0.8 m x 0.9 m x 1.0 m) and floored with perforated plastic. The left and right areas were painted (left: white, right: blue, based on33), and two tactile cues were fixed on each wall at 20 cm height and 28 cm apart (left: ceramic drawer knobs [Allen + Roth, CR6001-33-CW], right: plastic door stoppers [ReliaBilt, 20276PHXLG]). The middle area was painted grey and did not have tactile cues. Depending on the stage of the experiment, areas of the box were separated by either full dividers (during treatments), or dividers with openings allowing piglets access between the different areas (pre-test and test). The apparatus was slightly modified for Trial 5 by adding small movable gates allowing active conditioning during treatment sessions (see “Protocol” section). During winter, overhead heat lamps were installed to ensure uniform temperatures in the apparatus.

Place conditioning apparatus. Piglets received both treatments (castration or enrichment and sham, counterbalanced) in the side pens, differentiated by wall colour (blue or white) and tactile cues (door stoppers or drawer knobs). Middle walls could be gated to either restricting piglets to one pen during conditioning, or allowing access to all pens during pre-tests and tests. Illustration by Ann Sanderson.

Protocol

Identical parts of the different trials will be described first, then specific sections for each trial will be detailed in separate sections. A summary table is presented below (Table 1).

All trials

On their enrollment day (pre-test), piglets were numbered with a marker (Sharpie permanent marker, 15101PP), and weighed. They were then individually transported to the experimental apparatus (approximately 20 to 30 m away) in a cart bedded with straw. Piglets were gently lowered and released in the center of the middle (grey) area, facing the back wall. The apparatus was mounted with open dividers, allowing piglets to explore all areas. Piglets were left in the apparatus for the duration of pre-test (trial dependent), and latencies to enter and time spent in each area were video recorded and transcribed live. Piglets were then gently removed from the apparatus, placed in the cart, and brought back to their home pen. Piglets needed to explore at least one side pen (Fig. 1) during pre-test to be enrolled in the study, which was an effort to exclude piglets for which maternal separation resulted in immobilization and/or the propensity to freeze. Three piglets did not fulfill this criterion. Additionally, 7 piglets were excluded for health reasons or death (4 lame and 3 crushed in their home pen). In the event of exclusion, additional piglets were enrolled to reach a sample size of 22 for each trial.

On the day following pre-test, piglets received their first treatment. During treatments, piglets were removed from their home pen and brought to the experimental apparatus. Type of treatment, duration, and number of treatment sessions varied with trial. Regardless, all trials compared two treatments: an affective intervention (positive: enrichment or negative: castration), and a control. For all trials, treatment order and side associated with treatment were balanced by block across piglets. The aim was for the piglets to associate one side area with the affective intervention, and the other area with the control procedure. After receiving all treatment sessions, piglets were tested for place aversion or preference. Similarly to pre-tests, piglets were brought to the experimental apparatus which had open dividers for individual testing. Piglets were gently lowered in the middle area and were free to roam between all areas for the same amount of time allotted during pre-test (trial dependent). After the test, piglets were brought back to their home pen and returned to routine farm care.

Trial 1 (castration)

Trial 1 was a study of negative affective valence, using surgical castration as a model of a procedure inducing negative affect. Piglets (n = 22, [mean ± SD] age = 6.9 ± 0.7 d, 2.5 ± 0.6 kg) had 10 min to roam between pens during pre-test and test. Considering the unfeasibility of conducting castration multiple times on the same piglets, the number of treatment sessions was limited to two (one for each treatment: surgical and sham castration). During treatments, piglets were brought to the experimental apparatus then gently lowered in one of the two side areas which were mounted with the full dividers to prevent exploration to other areas. Piglets were left in the area for 5 to 10 min before receiving their assigned treatment (castration or sham) and then remained in the area for another 2 h as a pair to avoid isolation stress. After being brought back to their home pen and provided 48 h of rest, piglets received their second treatment: sham procedure if they had been castrated during their first treatment, and vice-versa. Similarly, if they had received their first treatment in the white pen, they received their second in the blue, and vice-versa.

For castrations, piglets were picked up from their pen, held upside down and their scrotum was sprayed with iodine (3.5 mL, Pivodine scrub, Vet One, diluted to 4%) and lidocaine (3.0 mL, 2% Lidocaine Hydrochloride, Burn Relief, Radix Labs). Spray-on anesthesia was used as routine farm practice to reduce handling and avoid injection pain associated with intratesticular methods of anesthesia delivery20,34,35,36. Then, two incisions were made by scalpel on their scrotum and the testicles were pushed out and removed by pull. The wound was then sprayed again with iodine and lidocaine, and piglets were gently put back in their area.

For sham treatments, a similar procedure with identical handling and pharmaceutical treatments was conducted, but no scrotum incision was made. Instead, light pressure was applied with fingers on either side of the scrotum.

Piglets were tested for place aversion for 10 min, 48 h after receiving their second treatment.

Trial 2 (Enrichment, single session)

The remainder of trials were studies of positive affect, using enrichment as a model. To maintain consistency and compare results, Trial 2 experimental design was identical to Trial 1 (i.e. one session per treatment, 2 h long, with 48 h rest between sessions, a social partner present during treatments, and 10 min during pre-test and test). During the affective intervention session, piglets (n = 22, 5.0 ± 0.0 d, 2.3 ± 0.5 kg) were placed in a pen bedded with straw that had been rubbed on their dam for a few seconds. A tennis ball (Penn 2, Arizona, USA), a pickleball (Monarch, DICK’S, Pennsylvania, USA), 8 ropes hanging from the wall (1.5 cm diameter, 3-strand cotton rope), one funnel toy (Bite-Rite, Farmer Boy, Pennsylvania, USA) and two waterers (Weaver Livestock, Ohio, USA) filled with 1% sucrose solution25 were available to the piglets. The control procedure took place in a barren pen (no straw, toys or sucrose solution) and was identical to Trial 1 (i.e. sham castration).

Trial 3 (Enrichment, repeated sessions)

Trial 3 was designed based on de Jonge and colleagues9, to explore the use of numerous, shorter treatment sessions. Piglets (n = 22, 5.2 ± 0.4 d, 2.1 ± 0.5 kg) were subjected to treatments identical to Trial 2 (enriched pen vs. sham castration), but sessions only lasted 3 min, and took place twice a day (once in the morning at approximately 10 AM, and once in the afternoon at approximately 2 PM, one of each treatment) every day for 5 consecutive days (for a total of 10 treatment sessions, 5 of each of treatment). Order of treatment was alternated everyday (e.g. if sham treatment was received in the morning on day 1, it was received in the afternoon on day 2). Pre-test and test lasted 1 min each9.

Trial 4 (Enrichment, older piglets)

Trial 4 was identical to Trial 3 (enriched pen vs. sham, 10 short treatment sessions), but conducted with older piglets (n = 22, 23.3 ± 1.6 d, 6.8 ± 1.0 kg). Pre-test and test lasted 3 min each9 to homogenise session durations between pre-test, test and treatments.

Trial 5 (Enrichment, active conditioning)

Trial 5 was designed to explore whether making active choices during conditioning (rather than simply being placed in the conditioning pen) helps piglets make an association between pen and treatment. To ensure all piglets (n = 22, 20.6 ± 3.4 d, 5.1 ± 0.8 kg) would experience both treatments (enriched pen and sham castration) at least once, they received passive conditioning on the first day (identical to Trial 3 and 4). For the following days (2 to 5), piglets received two daily conditioning sessions of 3 min each (morning and afternoon) similar to Trials 3 and 4, but piglets were placed in the middle gray pen (Fig. 1) with access to both side pens (one enriched, one barren). Piglets had 3 min to make a choice (i.e. fully enter one of the side pens). If they did, a small gate was lowered behind them, restricting them to the side pen for the remainder of the 3 min. If they entered the enriched pen, they were left to interact. If they entered the barren pen, experimenters conducted the sham castration and put them back down. If they had not entered a side pen after 3 min, they were brought back to their home pen and the session was recorded as a “No choice”. Due to the potential influence of a partner on choice made, sessions were conducted individually. After 8 active conditioning sessions (which also acted as preference choice tests), a regular 3 min place conditioning test was conducted at least 1 h after their last training (i.e. in the absence of enrichment in both pens, as in previous trials).

Statistical analysis

For each trial, latencies to enter and time spent in treatment pens were separately analyzed with mixed linear models from R’s lme4 package37,38. Fixed factors were treatment (sham vs. castration or enrichment) as well as treatment order, pen colour associated with treatments and the interaction between sessions (from pre-test to test). Slope for each treatment was compared to a theoretical null slope representing no change between pre-test and test. Piglet ID was used as a random factor nested within litter ID. Model residuals were checked for assumptions of linearity, normality and homoscedasticity. To fulfill these assumptions, models on latencies required data transformations (logarithmic for trials 1 and 2, square-root for trials 3–5). Models analyzing time spent did not require data transformation.

For trial 5, choices made during the active conditioning sessions were analyzed with a binomial general linear mixed model38. For all models, P-values were obtained with the lmerTest package39. Significance threshold was set at P < 0.05 (tendency at P < 0.10). 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained with R’s confint function and reported for significant results and tendencies.

Results

Place conditioning tests (trials 1–5)

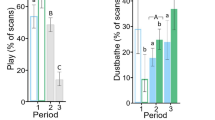

For all 5 trials, treatment order and colour of pen were not significant on both latency to enter pens and time spent in pens (P > 0.10). In trial 1 (sham vs. castration, young piglets, one conditioning session per treatment), piglets significantly increased their latency to enter the sham pen between pre-test and test (t = 2.4, P = 0.02, CI [0.11, 1.18]) and tended to have an increase in latency for the castration pen (t = 1.7, P = 0.09, CI [− 0.07, 0.99]). No differences were found for time spent (sham: t = − 1.6, P = 0.11; castration: t = 0.44, P = 0.66) (Fig. 2).

Place conditioning results for Trial 1 (Sham vs. Castration, young piglets, 2 treatment sessions of 2 h each). All piglets received both treatments between pre-test and test. Symbols represent significance (*P < 0.05) or tendency (‡P < 0.10) in changes between pre-test and test for each treatment (left: latency to enter, right: total time spent in the pen).

In trial 2 (sham vs. enrichment, young piglets, one conditioning session per treatment), no changes in latency or time spent between pre-test and test were observed (latency, sham: t = 0.05, P = 0.96; latency, enrichment: t = 0.32, P = 0.75; time, sham: t = − 0 .36, P = 0.72; time, enrichment: t = 0.52, P = 0.61) (Fig. 3). Similarly, no changes were observed in trial 3 when comparing sham to enrichment for young piglets, but with 5 conditioning sessions per treatment (latency, sham: t = 1.34, P = 0.19; latency, enrichment: t = 0.54, P = 0.59; time, sham: t = − 1.62, P = 0.11; time, enrichment: t = − 0.60, P = 0.55) (Fig. 4). In trial 4 (sham vs. enrichment, older piglets, five conditioning sessions per treatment), piglets took longer to enter both sham and enrichment pens between pre-test and test (sham: t = 5.2, P < 0.001, CI [2.63,5.77]; enrichment: t = 4.0, P < 0.001, CI [1.70, 4.85]). Time spent in the sham pen decreased across sessions (t = − 2.43, P = 0.02, CI [− 43.1, − 4.99]) while there was no difference in time spent in the enrichment pen (t = − 1.07, P = 0.29, CI [− 29.7, 8.42]) (Fig. 5). In trial 5 (sham vs. enrichment, older piglets, one passive and four active conditioning sessions per treatment), piglets showed an increase in latency to enter both pens. This increase was significant for the sham pen (t = 3.31, P = 0.001, CI [1.25,4.70]) and a tendency for the enrichment pen (t = 1.77, P = 0.08, CI [-0.13,3.32]). Piglets also tended to spend less time in the sham pen (t = − 1.92, P = 0.06, CI [− 36.2, 0.07]), whereas no changes were found for the enrichment pen (t = −0.50, P = 0.62, CI [− 22.9, 13.4]) (Fig. 6).

Place conditioning results for Trial 2 (Sham vs. Enrichment, young piglets, 2 treatment sessions of 2 h each). All piglets received both treatments between pre-test and test. Symbols represent significance (*P < 0.05) or tendency (‡P < 0.10) in changes between pre-test and test for each treatment (left: latency to enter, right: total time spent in the pen).

Place conditioning results for Trial 3 (Sham vs. Enrichment, young piglets, 10 treatment sessions of 3 min each). All piglets received treatments between pre-test and test. Symbols represent significance (*P < 0.05) or tendency (‡P < 0.10) in changes between pre-test and test for each treatment (left: latency to enter, right: total time spent in the pen).

Place conditioning results for Trial 4 (Sham vs. Enrichment, older piglets, 10 treatment sessions of 3 min each). All piglets received treatments between pre-test and test. Symbols represent significance (*P < 0.05) or tendency (‡P < 0.10) in changes between pre-test and test for each treatment (left: latency to enter, right: total time spent in the pen).

Place conditioning results for Trial 5 (Sham vs. Enrichment, older piglets, 10 treatment sessions of 3 min each, 2 of passive conditioning, 8 of active conditioning). All piglets received treatments between pre-test and test. Symbols represent significance (*P < 0.05) or tendency (‡P < 0.10) in changes between pre-test and test for each treatment (left: latency to enter, right: total time spent in the pen).

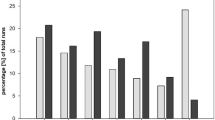

Active conditioning (trial 5)

Over all sessions of active conditioning, piglets made no choice on 63 occurrences, chose the enrichment pen 64 times and the sham pen 49 times. When looking at choices across sessions, an interaction was found between session number and type of choice made (X2 = 6.63, P = 0.04). The decrease in ‘No choices’ made throughout sessions was significant (z = −2.08, P = 0.04, CI [-0.29, -0.01]), and different from the evolution of choices for sham and enrichment pens (sham: z = 2.14, P = 0.03, CI [0.02, 0.42]; enrichment: z = 2.29, P = 0.02, CI [0.03, 0.42]). No differences were found between the evolution of choices for the sham and enrichment pens (z = 0.07, P = 0.95) (Fig. 7).

No correlation was found between the number of choices made for a pen during active conditioning and the latency to enter that pen during testing (sham: t = −0.55, P = 0.59; enrichment: t = −0.81, P = 0.43). Similarly, no correlation was found between the number of choices made for a pen during active conditioning and the time spent in that pen during testing (sham: t = 1.32, P = 0.20; enrichment: t = 1.30, P = 0.21).

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations, young piglets, ~ 1 week of age, did not significantly decrease their time spent in a pen associated with the presumed negative experience of castration (trial 1) or increased their time spent in a pen associated with the presumed positive experience of enrichment (trial 2). Their time spent in the presumed neutral sham pen also was unchanged in either trial. Similarly, for older piglets, ~ 3 weeks of age, no increase in time spent in the enriched pen was observed (trial 3), however, we noted a decrease in time spent in the sham pen (trial 4 and 5). These findings suggest that only older piglets exhibited a place conditioning response and benefitted from repeated conditioning (either active or passive), though they interestingly developed an aversion to the sham procedure rather than a preference for enrichment.

Active conditioning (trial 5) allows subjects more agency over the treatments they experience and resulted in piglets choosing neither pen quite frequently (36% of the time) as well as yielded fewer total treatment exposures than with passive conditioning (trial 4). All passively conditioned piglets were exposed to 5 sham and 5 enrichment treatments whereas the actively conditioned animals averaged 3.2 sham and 3.9 enrichment exposures. Interestingly, outcomes were somewhat similar between both types of conditioning, despite active conditioned piglets experiencing fewer conditioning exposures. Agency during conditioning suggests a more efficient way for animals to learn the association between entering a pen and experiencing its accompanying treatment. Further research is required, as our results do not depict a simple linear relationship between number of choices made during active conditioning and responses during place conditioning tests. Nevertheless, agency has been noted as an important component of animal welfare40,41,42 and researchers should aim to promote its integration in experimental designs.

Results from the latency to enter treatment pens during tests were also not supportive of our prediction that castration and enrichment would lead to - respectively - an increase and decrease in latency to enter these pens. When we observed a difference in initial approach between pre-tests and tests (trials 1, 4 and 5), it was an increase and appeared to affect the time to enter both treatment and sham pens regardless of their hypothesized valence. Because novelty plays an important role in exploration43 it is possible piglets displayed increased exploratory behavior towards the beginning of the testing period that gradually decreased over time as they became acclimated to the testing apparatus, leading to an increase in latency. Alternatively, latency increase could be explained by the development of a potential aversion to the conditioning process itself. Because fear has been found to lead to a freezing response in some pigs44, stressful scenarios such as separation from the dam and littermates during testing periods45,46 could have caused piglets to remain in the neutral pen and wait for the testing period to conclude, but it remains unclear why this response was not found in trials 2 and 3. Attempts were made to reduce the negative effects of separation and handling by transporting piglets with littermates and treating in pairs when possible.

The absence of a conditioned aversion and preference to castration and enrichment could be caused by several non-exclusive factors. First, piglets might have not been able to establish the association between pen and treatment. Subject age appeared as a relevant factor, with younger animals seemingly too young for our paradigm (trials 1–3). It seems unlikely that young pigs lack appropriate neural function to make associations with spatial cues as they establish a nursing order early in life. Individual pigs return hour after hour to a specific teat on the udder to nurse with great fidelity by 7 days of age47 exhibiting capable spatial memory. All piglets enrolled in this study were not weaned and separation from the dam is stressful to piglets45. Thus it is likely that the unweaned piglets were negatively impacted by the social isolation caused by individual testing, and could have been distracted from the experimental conditions and/or hindered their learning48. Conducting tests in pairs or groups might lessen isolation stress but would also raise interpretative challenges: does a piglet go to a pen simply because another piglet is in it, or alternatively is it avoiding an antagonistic partner? An interesting application is the use of “social windows” where subjects are tested individually but have visual and auditory access to social partners (Sara Hintze, personal communication).

It is also unclear how having piglets in pairs during treatments might have affected their conditioning. Social buffering49 could have helped minimize stress (hence affective contrast), but the opposite mechanism of emotional contagion50 might also have taken place. Unfortunately, such interpretation remains speculative as the influence of social dynamics on affective processes remains largely unknown in pigs.

We used multi-sensory cues to maximize the likelihood of associative learning (spatial: left vs. right, visual: wall paint color, tactile: household hardware)51,52, but these cues might not have been sufficiently behaviorally relevant to the piglets or not well adapted to piglet sensory capabilities. Our choices of conditioned stimuli were influenced by studies on rodents which constitute the large majority of the literature on place conditioning53. For future studies, we recommend shifting the focus to cues prone to be more pertinent to piglets such as olfaction54,55.

Another reason that could explain the lack of a conditioned aversion or preference was that treatments did not cause enough of an affective contrast with the sham procedure to induce a place conditioning response.

Our results are in accordance with previous reports on castration where topical anesthesia was effective in controlling pain for 2 h after surgical castration56,57. The place conditioning responses we observed reflected the experience of the piglets over 2 h including both the procedure and its recovery. However, the contribution of each phase (either procedure or recovery) to the response remains unclear. Severing of the spermatic cord appears to be the most painful moment of castration34 : although topical anesthesia induced a reduction of vocal response during cord traction, no difference was found with placebo-treated piglets for the remainder of the procedure56. Similarly, castrated piglets had higher serum cortisol levels 1 h after the procedure, but at 2 h no differences were observed58. It is possible that the lack of a conditioned response resulted from the duration of the treatment which allowed for a recovery period that perhaps inadvertently mitigated the memory of the aversive impact of the procedure itself. It is also unknown whether the pre-test and test phases which consisted of social isolation in barren compartments induced negative associations with the whole experimental apparatus, further reducing the affective contrast between treatment pens.

We would like to emphasize that our study used castration as a negative valence model, only focusing on 2 h post-procedure. This was by design to limit isolation from the sow, but pain following castration is likely to last longer than 2 h, perhaps days or weeks although common pain measures might not be sensitive enough to detect changes59.

We also note that castration was not a repeatable treatment and was conducted only on ~ 1 week old piglets for ethical reasons. It is unclear whether repeated negative interventions on older piglets would have led to place aversion. We focused on castration because of its welfare relevance60,61, but other interventions such as handling or injections might be better fits of negative valence models62,63 .

Several studies have found a positive effect of enrichment on weight gain64, aggression mitigation65, cognitive measures66,67,68 and other welfare assessments69, however, not all studies report positive outcomes. For example, no behavioural differences were found in pre-weaned piglets whether they were provided straw or not70, and pigs were not found to differ in their judgment bias (i.e. their optimistic or pessimistic views on ambiguous stimuli71) regardless of being housed in a barren or enriched environment72. Henzen and Gygax73 did not find differences in physiological and activity outcomes in anticipation of presumed positive (sawdust, popcorn, feed balls) or negative stimuli (isolation, inaccessible feed, sudden noise and movement), perhaps because their outcomes were more reflective of affective arousal than valence.

Several reasons could explain the lack of a strong positive affect linked to enrichment in our studies. In their first weeks of life, it is possible that contact with the dam and littermates supersedes the relevance of any other stimuli, or that the environmental enrichment we provided was not attractive enough. Although straw was rubbed on the dam to add an olfactory component to the enrichment, perhaps supplementing the straw with additional stimulating components such as peat74 or scented oils75,76 would have made the enrichment more impactful. Psychological processes such as habituation could also be at play: conditioning sessions were either long (2 h, trial 2) or repeated (5 occurrences, trials 3–5) with unchanging enrichment. As novelty has been emphasized as an important aspect of engaging stimulation22, the presented enrichment might have lost its positive value with extended or repeated exposure. Another possibility was that enrichment was positive, but removal from this positive environment was a negative event which prevented the development of conditioned preference. Other work has suggested a decline in environment quality leads to reduced welfare as removal of enrichment increased redirected behaviours such as tail biting77 and decreasing exploratory behaviours78.

Another important point to consider is that we only enrolled males because of our choice to use castration as a negative event. Although some studies report little to no effect of sex on cognitive tasks68,79, notable sex differences in learning and conditioning processes have been observed in several species80 including pigs81,82. Our results might also be specific to the genetic lines used, as Kratzer83 noted breed differences in avoidance learning performances. Finally, we did not account for parental influences such as personality or housing conditions, which have recently been noted to affect offspring behavioural responses84,85,86.

Conclusion

We did not find clear evidence of place conditioned aversion for castration or preference for enrichment. Rather, our results suggest that older piglets (approximately 3 weeks old) developed an aversion to the sham procedure when paired with enriched conditions. This result was consistent for both passive and active conditioning methodologies, although active appears to be a more efficient approach. We argue that young piglets failed to establish a strong association between pen and treatment for several possible reasons including their young age, removal from the litter, inappropriate cues, or low affective contrast between treatment and sham procedures. Evaluation of emotional states in young animals is challenging, but place conditioning appears in some instances to be a promising avenue for assessment of affective valence. This work provides methodological groundwork on the application of place conditioning in piglets and highlights the nuances important for the use of cognitive tests to assess animal welfare.

References

Mendl, M. & Paul, E. S. Animal affect and decision-making. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 112, 144–163 (2020).

Fraser, D., Weary, D. M., Pajor, E. A. & Milligan, B. N. A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim Welf. 6, 187–205 (1997).

Mendl, M., Burman, O. H. P. & Paul, E. S. An integrative and functional framework for the study of animal emotion and mood. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 277, 2895–2904 (2010).

Kremer, L., Klein Holkenborg, S. E. J., Reimert, I., Bolhuis, J. E. & Webb, L. E. The nuts and bolts of animal emotion. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 113, 273–286 (2020).

Tzschentke, T. M. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: A comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Prog. Neurobiol. 56, 613–672 (1998).

Noye Tuplin, E. W. & Holahan, M. R. Exploring time-dependent changes in conditioned place preference for food reward and associated changes in the nucleus accumbens. Behav. Brain. Res. 361, 14–25 (2019).

Calcagnetti, D. J. & Schechter, M. D. Place conditioning reveals the rewarding aspect of social interaction in juvenile rats. Physiol. Behav. 51, 667–672 (1992).

Lepore, M., Vorel, S. R., Lowinson, J. & Gardner, E. L. Conditioned place preference induced by ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol: Comparison with cocaine, morphine, and food reward. Life Sci. 56, 2073–2080 (1995).

de Jonge, F. H., Tilly, S. L., Baars, A. M. & Spruijt, B. M. On the rewarding nature of appetitive feeding behaviour in pigs (Sus scrofa): Do domesticated pigs contrafreeload? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 114, 359–372 (2008).

Imfeld-Mueller, S., Van Wezemael, L., Stauffacher, M., Gygax, L. & Hillmann, E. Do pigs distinguish between situations of different emotional valences during anticipation? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 131, 86–93 (2011).

Karas, G. G., Willham, R. L. & Cox, D. F. Avoidance learning in swine. Psychol. Rep. 11, 51–54 (1962).

Mormede, P. & Dantzer, R. Experimental studies on avoidance behaviour in pigs. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 3, 173–185 (1977).

Burkemper, M. C., Pairis-Garcia, M. D., Moraes, L. E., Park, R. M. & Moeller, S. J. Effects of oral meloxicam and topical lidocaine on pain associated behaviors of piglets undergoing surgical castration. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 23, 209–218 (2020).

Kluivers-Poodt, M., Zonderland, J. J., Verbraak, J., Lambooij, E. & Hellebrekers, L. J. Pain behaviour after castration of piglets; effect of pain relief with lidocaine and/or meloxicam. Animal. 7, 1158–1162 (2013).

Puppe, B., Schön, P. C., Tuchscherer, A. & Manteuffel, G. Castration-induced vocalisation in domestic piglets, Sus scrofa: Complex and specific alterations of the vocal quality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 95, 67–78 (2005).

Taylor, A. A., Weary, D. M., Lessard, M. & Braithwaite, L. Behavioural responses of piglets to castration: The effect of piglet age. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 73, 35–43 (2001).

Bonastre, C. et al. Acute physiological responses to castration-related pain in piglets: The effect of two local anesthetics with or without meloxicam. Animal. 10, 1474–1481 (2016).

Sutherland, M. A., Davis, B. L., Brooks, T. A. & McGlone, J. J. Physiology and behavior of pigs before and after castration: Effects of two topical anesthetics. Animal. 4, 2071–2079 (2010).

Scollo, A. et al. Analgesia and/or anaesthesia during piglet castration—part I: Efficacy of farm protocols in pain management. Italian J. Anim. Sci. 20, 143–152 (2021).

Saller, A. M. et al. Local anesthesia in piglets undergoing castration: A comparative study to investigate the analgesic effects of four local anesthetics on the basis of acute physiological responses and limb movements. PLoS ONE 15, e0236742 (2020).

Petersen, V., Simonsen, H. B. & Lawson, L. G. The effect of environmental stimulation on the development of behaviour in pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 45, 215–224 (1995).

Van de Weerd, H. A., Docking, C. M., Day, J. E. L., Avery, P. J. & Edwards, S. A. A systematic approach towards developing environmental enrichment for pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 84, 101–118 (2003).

Horrell, I. & Ness, P. A. Enrichment satisfying specific behavioural needs in early-weaned pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2–4, 264 (1995).

Day, J. E. L., Kyriazakis, I. & Lawrence, A. B. An investigation into the causation of chewing behaviour in growing pigs: The role of exploration and feeding motivation. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 48, 47–59 (1996).

Figueroa, J., Solà-Oriol, D., Manteca, X., Pérez, J. F. & Dwyer, D. M. Anhedonia in pigs? Effects of social stress and restraint stress on sucrose preference. Physiol. Behav. 151, 509–515 (2015).

Chaloupková, H., Illmann, G., Bartoš, L. & Špinka, M. The effect of pre-weaning housing on the play and agonistic behaviour of domestic pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 103, 25–34 (2007).

Martin, J. E., Ison, S. H. & Baxter, E. M. The influence of neonatal environment on piglet play behaviour and post-weaning social and cognitive development. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 163, 69–79 (2015).

Beattie, V. E., O’Connell, N. E. & Moss, B. W. Influence of environmental enrichment on the behaviour, performance and meat quality of domestic pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 65, 71–79 (2000).

Schaefer, A. L., Salomons, M. O., Tong, A. K. W., Sather, A. P. & Lepage, P. The effect of environment enrichment on aggression in newly weaned pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 27, 41–52 (1990).

Telkänranta, H., Swan, K., Hirvonen, H. & Valros, A. Chewable materials before weaning reduce tail biting in growing pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 157, 14–22 (2014).

Peeters, E., Driessen, B., Moons, C. P. H., Ödberg, F. O. & Geers, R. Effect of temporary straw bedding on pigs’ behaviour, performance, cortisol and meat quality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 98, 234–248 (2006).

Global Animal Partnership’s (GAP) 5-step Animal Welfare Standards for Pigs v2.5. (2014).

Tanida, H., Senda, K., Suzuki, S., Tanaka, T. & Yoshimoto, T. Color discrimination in Weanling pigs. Nihon Chikusan Gakkaiho 62, 1029–1034 (1991).

Rault, J. L., Lay, D. C. & Marchant-Forde, J. N. Castration induced pain in pigs and other livestock. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 135, 214–225 (2011).

Werner, J. et al. Evaluation of two injection techniques in combination with the Local Anesthetics Lidocaine and Mepivacaine for piglets undergoing Surgical Castration. Animals. 12, 1028 (2022).

Skade, L., Kristensen, C. S., Nielsen, M. B. F. & Diness, L. H. Effect of two methods and two anaesthetics for local anaesthesia of piglets during castration. Acta Vet. Scand. 63, 1 (2021).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Soft 67, (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Špinka, M. Animal agency, animal awareness and animal welfare. Anim Welf. 28, 11–20 (2019).

Englund, M. D. & Cronin, K. A. Choice, control, and animal welfare: Definitions and essential inquiries to advance animal welfare science. Front. Vet. Sci. 10 (2023).

Littlewood, K. E., Heslop, M. V. & Cobb, M. L. The agency domain and behavioral interactions: Assessing positive animal welfare using the five domains model. Front. Vet. Sci. 10 (2023).

Mkwanazi, M. V., Ncobela, C. N., Kanengoni, A. T. & Chimonyo, M. Effects of environmental enrichment on behaviour, physiology and performance of pigs: A review. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 32, 1–13 (2019).

Dalmau, A., Fabrega, E. & Velarde, A. Fear assessment in pigs exposed to a novel object test. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 117, 173–180 (2009).

Van Kerschaver, C., Turpin, D., Michiels, J. & Pluske, J. Reducing weaning stress in piglets by pre-weaning socialization and gradual separation from the sow: A review. Animals. 13, 1644 (2023).

Kanitz, E. et al. A single exposure to social isolation in domestic piglets activates behavioural arousal, neuroendocrine stress hormones, and stress-related gene expression in the brain. Physiol. Behav. 98, 176–185 (2009).

De Passille, A. M., Rushen, J. & Hartsock, T. G. Ontogeny of teat fidelity in pigs and its relation to competition at suckling. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 68, 325–338 (1988).

Joëls, M., Pu, Z., Wiegert, O., Oitzl, M. S. & Krugers, H. J. Learning under stress: How does it work? Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 152–158 (2006).

Reimert, I., Bolhuis, J. E., Kemp, B. & Rodenburg, T. B. Social support in pigs with different coping styles. Physiol. Behav. 129, 221–229 (2014).

Reimert, I., Bolhuis, J. E., Kemp, B. & Rodenburg, T. B. Indicators of positive and negative emotions and emotional contagion in pigs. Physiol. Behav. 109, 42–50 (2013).

Cunningham, C. L., Patel, P. & Milner, L. Spatial location is critical for conditioning place preference with visual but not tactile stimuli. Behav. Neurosci. 120, 1115–1132 (2006).

Bucci, D. J., Saddoris, M. P. & Burwell, R. D. Contextual fear discrimination is impaired by damage to the postrhinal or perirhinal cortex. Behav. Neurosci. 116, 479–488 (2002).

Tzschentke, T. M. & REVIEW ON, C. P. P. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: Update of the last decade. Addict. Biol. 12, 227–462 (2007).

Nowicki, J., Swierkosz, S., Tuz, R. & Schwarz, T. The influence of aromatized environmental enrichment objects with changeable aromas on the behaviour of weaned piglets. Veterinarski Arhiv. 85, 425–435 (2015).

McGlone, J. J. Olfactory signals that modulate pig aggressive and submissive behavior. In Social Stress in Domestic Animals (Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, (1990).

Sheil, M., Chambers, M. & Sharpe, B. Topical wound anaesthesia: Efficacy to mitigate piglet castration pain. Aust. Vet. J. 98, 256–263 (2020).

Lomax, S., Harris, C., Windsor, P. A. & White, P. J. Topical anaesthesia reduces sensitivity of castration wounds in neonatal piglets. PLoS ONE. 12, e0187988 (2017).

Byrd, C., Radcliffe, J., Craig, B., Eicher, S. & Lay, D. Measuring piglet castration pain using linear and non-linear measures of heart rate variability. Anim Welf. 29, 257–269 (2020).

Prunier, A., Tallet, C. & Sandercock, D. Evidence of pain in piglets subjected to invasive management procedures. In Understanding the Behaviour and Improving the Welfare of Pigs (Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, (2020).

von Borell, E. et al. Animal welfare implications of surgical castration and its alternatives in pigs. Animal 3, 1488–1496 (2009).

Prunier, A. et al. A review of the welfare consequences of surgical castration in piglets and the evaluation of non-surgical methods. Anim Welf. 15, 277–289 (2006).

Dalmau, A. et al. Intramuscular vs. intradermic needle-free vaccination in piglets: Relevance for Animal Welfare based on an aversion learning test and vocalizations. Front. Vet. Sci. 8 (2021).

Brajon, S. et al. Persistency of the piglet’s reactivity to the handler following a previous positive or negative experience. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 162, 9–19 (2015).

Oliveira, R. F. et al. Environmental enrichment improves the performance and behavior of piglets in the nursery phase. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 68, 415–421 (2016).

De Jonge, F. H., Bokkers, E. A. M., Schouten, W. G. P. & Helmond, F. A. Rearing piglets in a poor environment: Developmental aspects of social stress in pigs. Physiol. Behav. 60, 389–396 (1996).

Douglas, C., Bateson, M., Walsh, C., Bédué, A. & Edwards, S. A. Environmental enrichment induces optimistic cognitive biases in pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 139, 65–73 (2012).

Grimberg-Henrici, C. G. E., Vermaak, P., Elizabeth Bolhuis, J., Nordquist, R. E. & van der Staay, F. J. Effects of environmental enrichment on cognitive performance of pigs in a spatial holeboard discrimination task. Anim. Cogn. 19, 271–283 (2016).

Sneddon, I. A., Beattie, V. E., Dunne, L. & Neil, W. The effect of environmental enrichment on learning in pigs. Anim Welf. 9, 373–383 (2000).

Godyń, D., Nowicki, J. & Herbut, P. Effects of environmental enrichment on pig welfare—a review. Animals 9, 383 (2019).

Statham, P., Green, L. & Mendl, M. A longitudinal study of the effects of providing straw at different stages of life on tail-biting and other behaviour in commercially housed pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 134, 100–108 (2011).

Roelofs, S., Boleij, H., Nordquist, R. E. & van der Staay, F. J. Making decisions under ambiguity: Judgment Bias tasks for assessing emotional state in animals. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10 (2016).

Marsh, L. et al. Evaluation of miRNA as biomarkers of emotional valence in pigs. Animals 11, 2054 (2021).

Henzen, A. & Gygax, L. Weak General but no specific habituation in anticipating stimuli of presumed negative and positive Valence by Weaned piglets. Animals. 8, 149 (2018).

Luo, L. et al. Effects of early life and current housing on sensitivity to reward loss in a successive negative contrast test in pigs. Anim. Cogn. 23, 121–130 (2020).

Blackie, N. & de Sousa, M. The use of garlic oil for olfactory enrichment increases the use of ropes in weaned pigs. Animals 9, 148 (2019).

Rørvang, M. V. et al. Rub ‘n’ roll – pigs, Sus scrofa domesticus, display rubbing and rolling behaviour when exposed to odours. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 266, 106022 (2023).

Munsterhjelm, C. et al. Experience of moderate bedding affects behaviour of growing pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 118, 42–53 (2009).

Melotti, L., Oostindjer, M., Bolhuis, J. E., Held, S. & Mendl, M. Coping personality type and environmental enrichment affect aggression at weaning in pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 133, 144–153 (2011).

Roelofs, S., van Bommel, I., Melis, S., van der Staay, F. J. & Nordquist, R. E. Low birth weight impairs acquisition of spatial memory task in pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 5 (2018).

Dalla, C. & Shors, T. J. Sex differences in learning processes of classical and operant conditioning. Physiol. Behav. 97, 229–238 (2009).

Roelofs, S., Nordquist, R. E. & van der Staay, F. J. Female and male pigs’ performance in a spatial holeboard and judgment bias task. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 191, 5–16 (2017).

Fleming, S. A. & Dilger, R. N. Young pigs exhibit differential exploratory behavior during novelty preference tasks in response to age, sex, and delay. Behav. Brain. Res. 321, 50–60 (2017).

Kratzer, D. D. Effects of age on avoidance learning in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 28, 175–179 (1969).

Rooney, H. B., Schmitt, O., Courty, A., Lawlor, P. G. & O’Driscoll, K. Like mother like child: Do fearful sows have fearful piglets? Animals 11, 1232 (2021).

Sabei, L. et al. Inheriting the sins of their fathers: boar life experiences can shape the emotional responses of their offspring. Front. Anim. Sci. 4 (2023).

Lanthony, M., Briard, E., Špinka, M. & Tallet, C. Weaned piglet’s reactivity to humans, tonic immobility and behaviour in a spatial maze test is affected by gestating sows’ relationship to humans and positive handling at weaning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 268, 106080 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Swine Center manager Lori Stone and staff Nicole Fox, Jillian Mosley, Hanna Lee and Lainey Mikus for the routine care of animals during the study. This work was supported by the Marie A. Moore Endowed Fund for Welfare Research and the Wiederhold Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TE, SI and TDP conceived the experiment. TE and SI collected and analysed data. TE and SI wrote the initial draft. TE, SI and TDP reviewed and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ede, T., Ibach, S. & Parsons, T.D. Place conditioning as evaluation of affective valence in piglets. Sci Rep 14, 25216 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75849-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75849-5