Abstract

Background At present, the relationship between the Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) and Acute kidney injury (AKI) in traumatic brain injury patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is still unclear. Currently, the relationship between TyG index and AKI occurred within 7 days in the ICU is a highly researched and trending topic. Objective In this study, we conducted in-depth exploration of the relationship between the development of AKI in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients in the ICU and changes in TyG index, as well as its relevance. Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted with a total of 492 individuals enrolled in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV(MIMIC-IV) database. Multivariate model logistic regression, smoothed curve fitting and forest plots were utilized to confirm the study objectives. The predictive power of the TyG index for outcome indicators was assessed using subject work characteristics (ROC) curves. As well as comparing the Integrated Discriminant Improvement Index and the Net Reclassification Index of the traditional forecasting model with the addition of the TyG index. Results Of all eligible subjects, 55.9% were male and the incidence of AKI was 59.3%. There was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of AKI within 7 days in the ICU between the different TyG index groups. The difference between TyG index and the risk of AKI within 7 days in the ICU remained significant after adjustment for logistic multifactorial modeling (OR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.41–3.05, P < 0.001). A similar pattern of associations was observed in subgroup analyses (P values for all interactions were greater than 0.05). The addition of TyG index to the traditional risk factor model improved the predictive power of the risk of AKI within 7 days in ICU (P < 0.05). Conclusion The findings of this study demonstrate a strong association between the TyG index and the occurrence of AKI within 7 days in ICU patients. The TyG index can potentially be used as a risk stratification tool for early identification and prevention of AKI. Implementing preventive strategies targeting patients with a high TyG index may help reduce the burden of AKI in the ICU. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate these findings and explore the clinical utility of the TyG index in AKI prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

TBI has the highest prevalence of all common neurological disorders and poses a significant public health burden. It is estimated that TBI will remain one of the top three causes of injury-related death and disability through 2030. Overall, 50–60 million people suffer from TBI each year, costing the global economy an estimated $400 billion annually1. TBI is a leading cause of death and persistent neurocognitive impairment in adults and can lead to a variety of non-neurologic complications, including AKI2. According to published studies, the incidence of AKI in patients with TBI ranges from 3.9–24%3,4. Notably, the pathophysiologic effects of secondary brain injury can exacerbate the development of AKI after TBI5. Therefore, as neurosurgeons and ICU physicians, it is more important to pay attention to the occurrence and development of AKI in early stage patients and to reduce the number of drugs with high renal impairment6. In particular, the use of mannitol analogs should be reduced and the use of hypertonic saline should be increased in the treatment of intracranial pressure reduction7. As the global population ages, the burden of TBI patients in ICU is increasing. Therefore, it is crucial to identify indicators that can predict the occurrence of AKI in patients with TBI. These indicators should be straightforward, user-friendly, cost-effective, and easy to apply in a clinical setting.

Factors that can predict the occurrence of AKI in critically ill TBI patients are crucial. TyG index is a recognized indirect marker of insulin resistance (IR), combining fasting blood glucose (FBG) and triglyceride (TG) levels8,9,10. It has been widely used to assess the relationship between lipid metabolism and glycemic status and has been shown to be effective in predicting adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes11,12,13,14,15,16. Although the prognostic efficacy of TyG index in predicting the prediction of complications, recurrence, morbidity, and mortality in patients with other brain disorders and in other diseases has been demonstrated17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24.The role of TyG index in predicting the occurrence of AKI in patients with TBI, especially in critically ill patients, is unknown.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to test whether the TyG index can be used as a predictor of the occurrence of AKI in patients with TBI in the ICU. This may help to differentiate patients at higher risk for closer monitoring or early intervention.

Method

Data selection

This was a cross-sectional study, and the original data were obtained from the MIMIC-IV database. The MIMIC-IV database is a joint venture between the MIT Laboratory of Computational Physiology, the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) at Harvard Medical School, and Philips Healthcare. With funding from the National Institutes of Health, the database was launched in 200325.

In order to comply with the regulations, the author, Huang Jiang, obtained both a Cooperative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) license and the necessary permissions to use the MIMIC-IV database (ID: 12801436).

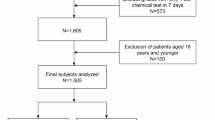

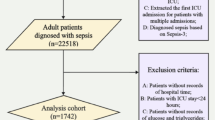

Inclusion criteria: Diagnosis of TBI (based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)). Exclusion criteria: (a) lack of admission to the ICU and (b) lack of triglyceride and blood glucose data. For patients with multiple admissions to the ICU, we chose the first admission. To ensure data completeness, we excluded patients with no AKI data, incomplete TG or glucose levels, or no follow-up 48 h after admission. Patients were divided into three groups according to the tertiles of the TyG index on day 1 in the ICU. For patients with multiple tests, the first test result within 24 h of ICU admission was used.

Data collection

Data collection consisted of extracting patient demographic characteristics, laboratory indicators, comorbidities, first day in and out of ICU, in-hospital mortality, and scores using the Structured Query Language (SQL) of PostgreSQL (version 16). Demographic information includes gender, age and race. Vital signs included heart rate, oxygen saturation (Spo2), systolic blood pressure (SBP) mean blood pressure (MBP). Laboratory indices included Red Blood Cell Distribution Width (RDW), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), white blood cell count (WBC), prothrombin time (PTT), creatinine, hemoglobin, blood calcium, blood glucose, blood sodium and blood potassium. Patient comorbidities and personal history were determined based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 and included AKI, sepsis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Scores included The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Acute Physiology Score III (APSIII), Oxford Acute Severity Score (OASIS), Sequential Organ Failure Score (SOFA), and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPSII).

The TyG index was calculated as follows: ln[(fasting TG (mg/dl) × FBG (mg/dl))/2]. The diagnostic criteria for sepsis 3.0 are as follows: infection and SOFA score of ≥ 2. For variables with a percentage of missing values greater than 25%, we directly deleted them; for variables with a percentage of missing values less than 25%, we used multiple interpolation(based on 5 replications and a chained equation approach method) to interpolate the missing values. For data before and after multiple interpolation, we performed a baseline profile comparison (Supplementary Table 1). Body mass index (BMI), glutamate aminotransferase, C-reactive protein, uric acid, and cystatin C all had missing values greater than 25%.

Outcome measures

The risk of acute kidney failure was the primary outcome of this study. According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)26guidelines, AKI is defined as a serum creatinine (SCr) level ≥ 0.3 mg/dL above baseline within 48 h or a urine output of < 0.5 mL/kg/h within 6 h.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages (%), and continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation (SD)) or median (interquartile spacing). Differences in continuous variables were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or rank sum tests. We used the maximum Yoden index to determine the best cut-off value for both and grouped the TyG index according to the best cut-off value. To compare the characteristics of subjects in the outcome group, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to assess the independent correlation between TyG index and the risk of developing AKI in patients with traumatic brain injury. TyG index was entered as a categorical variable (trichotomous) and as a continuous variable (with odds ratios (ORs) calculated for each incremental unit). Regression analyses using three models. The multivariate models were adjusted as follows: Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex and race; Model 3 was adjusted to Model 2 for GCS, apsiii, sapsii, oasis, sofa24, sepsis3, chronic pulmonary disease, myocardial infarct, renal disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, input1day and RDW. To prevent multicollinearity, variables with variance inflation factors greater than 5 were excluded from the model (Supplementary Table 2). A restricted cubic spline model was used to explore the possible linear relationship between TyG index and AKI. The lowest tertile of TyG index values was used as the analytical reference group to adjust for the above (Model 3) covariates. The tertile level was used as an ordinal variable to derive a p-value for trend. To further assess the effect of unmeasured confounders, we calculated the E-value.

Clinical decision curves and calibration plots (Supplementary Fig. 1) were plotted, and Integrated Discriminant Improvement (IDI)27 and Net Reclassification Index (NRI) were calculated separately to assess the improvement in predictive power and clinical value of the scoring tool by incorporating the TyG index. We further stratified analyses by age, sex, race, and sepsis and diabetes to determine the robustness of the TyG index in predicting AKI risk. To test the interaction between the TyG index and the stratification variables, we used the likelihood ratio test. To reduce the risk of category I errors (false positives), Least Significant Difference (LSD) and Bonferroni were performed to compare TyG index between groups in the event of AKI (Supplementary Table 3). A two tailed test was used in this study, and P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference. All analyses were performed using the R Statistical Package (http://www.R-project.org, R Foundation) and Free Statistical Software version 1.9.1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The MIMIC-IV project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre. Patient information was anonymised and informed consent was not required for this study. The ethical approval and participation consent followed the Helsinki Declaration guidelines.

Result

A total of 492 patients were finally included in this study. The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1. AKI was diagnosed in 292 patients (59.3%).The mean age of the patients was (68.9 ± 15.9) years and 275 patients (55.9%) were male. The mean TyG index of all subjects was (8.9 ± 0.7).

Study population characteristics

We determined the optimal cut-off value for both by maximising the Jordon’s index, where the sensitivity (66.8%) and specificity (63.5%) of the TyG index in predicting the occurrence of AKI reached its maximum value at 8.7052 points. We then changed the TyG index into a triple categorical variable based on the optimal cut-off value(three groups - Q1: 7.30–8.51; Q2: 8.51–9.05; and Q3: 9.05–12.10). Patients in the high TyG index group had elevated levels of sepsis, diabetes, GCS, apsiii score, sofa score, oasis score, BUN, WBC, and heart rate compared to the low TyG index group. The incidence of AKI (42.7% vs. 60.4% vs. 75%, P < 0.001) increased progressively with increasing TyG index (Table 1).

Univariate logistic regression analysis of the incidence rate of AKI

TyG index was a risk factor for AKI (Table 2). However, univariate analysis also showed that gender, age, ethnicity, BUN, calcium, LDH, heart rate, MBP, WBC, PTT, glucose, hemoglobin, sepsis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, Diabetes, GCS, apsiii score, sapsii score and Oasis score were the correlates of AKI (P < 0.05).

Logistic regression analysis of multifactorial TyG index and AKI

The TyG index was significantly associated with AKI after adjustment for multivariate analysis (Table 3). Logistic regression analyses using the TyG index as a continuous variable showed a significant correlation between AKI risk and the TyG index (model 1 OR, 2.98 [95% CI 2.15–4.14]; P < 0.001) in models 1 and 2 (model 2 OR, 2.79 [95% CI 2-3.91]; P < 0.001), fully adjusted model (OR, 2.07 [95% CI 1.41–3.05]; P < 0.001). In addition, using the TyG index as a categorical variable, the highest tertile (Q3) of the TyG index was significantly associated with the risk of AKI in the unadjusted model1 (Q1 vs. Q2: OR, 2. 05 [95% CI 1.32–3.18] p = 0.001; Q3: OR, 4.03 [95% CI 2.52–6.44] p = < 0.001) and fully adjusted models (Q1 vs. Q2: OR, 1.78 [95% CI 1.08–2.39] p = 0.023; Q3: OR, 2.21 [95% CI 1.27–3.84] p = 0.011). To further assess the effect of unmeasured confounders, E-value was calculated to estimate the magnitude of an unadjusted confounding variable needed to mitigate the association between TyG index and the incidence of AKI.E-value analysis showed that an unexplained confounder would need to be associated with both TyG index and AKI incidence at a odds ratio of 2.23 tomitigate the relationship between these variables, while controlling for other covariates in our model.

Restricted cubic spline regression model

Both the unadjusted and fully adjusted models showed a dose-response relationship between the TyG index and aki risk (nonlinear P = 0.677, nonlinear P = 0.781) (Fig. 2).

Restricted cubic spline curves for the TyG index hazard ratio. A: Model 1 was unadjusted. B: Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, and race. C: Model 3 was adjusted for the variables in model 2 and further adjusted for GCS, apsiii, sapsii, oasis, sofa24, sepsis3, chronic pulmonary disease, myocardial infarct, renal disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, input1day and RDW.

Predictive power and clinical benefit of the TyG index

We calculated the area under the ROC curve (AUC) to examine the ability of the TyG index to predict the occurrence of AKI in patients. The results showed that in patients with TBI, the TyG index predicted AKI with an AUC higher than 0.6 (IQR: 0.649 [0.602, 0.695]; numeric: 0.678 [0.631, 0.726]) (Fig. 3). In conclusion, the TyG index provides some predictive value for the occurrence of AKI in patients with TI. In addition, we plotted clinical decision curves to assess the improved clinical utility of the TyG index. The results showed that the net clinical benefit of each scoring tool also improved after considering the TyG index (Fig. 4). In addition, when considering the TyG index, we also calculated the IDI as well as the NRI of the scoring tools (APSIII, OASIS, SAPSII) to analyse the effect of the TyG index on the predictive ability of the scoring tools. The IDI and the NRI are both tools for assessing the degree of improvement in the predictive ability of a response model, with greater than 0 indicating a positive improvement, and less than 0 indicating a negative improvement. The predictive ability of the scoring tool for the incidence of AKI in patients with traumatic brain injury was significantly improved (P < 0.01) after considering the numerical TyG index (Table 4).

Stratified analysis of the incidence of AKI according to the TyG index

We further assessed risk predictors for the primary outcome TyG index in different subgroups of patients, including age, sex, race, sepsis and diabetes (Fig. 5). No interaction was found in the above subgroups.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was conducted as a retrospective study to investigate the relationship between the TyG index and the occurrence of AKI in patients with TBI in the ICU. The key finding in our results suggests that ICU patients with an elevated TyG index have a higher risk of developing AKI, even after adjusting for potential confounding variables. Our findings also showed that the prevalence of AKI in patients was linearly correlated with TyG index. Most importantly, a novel, simple, and effective biomarker for early warning of AKI in ICU patients was provided by this study. TBI is a major global public health problem, and the GBD 2019 study shows a significant increase in its burden between 1990 and 2019. TBI is not only life-threatening, but also has a high rate of disability, which is particularly severe in young people, resulting in significant disability, early death and long-term socioeconomic burden. Despite advances in medical technology, prevention and management of TBI remain challenging and require multifaceted efforts28. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore new biomarkers to identify patients with TBI who are at high risk of developing AKI in the ICU in order to improve their prognosis.

It has been shown that IR plays a key role in the development of traumatic brain injury and renal insufficiency, and it usually precedes the onset of these conditions29,30,31. Although homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) was once used as a simple tool for assessing IR32, it is costly, time-consuming and may involve invasive procedures, limiting its use in clinical routine. To address this issue, Unger G et al. proposed the TyG index in 2013 as a cost-effective, efficient and easily reproducible index of IR33.Comparison of several studies found that the TyG index outperformed the HOMA-IR in measuring IR, and therefore has greater appeal in clinical practice34,35,36.

In recent years, numerous clinical studies have continued to reveal that the TyG index has demonstrated significant associations in the assessment of the health of different populations, particularly with the incidence of cerebrovascular and renal diseases and mortality. This biomarker, based on triglyceride and blood glucose levels, is gradually gaining a lot of attention in the medical community because of its simplicity and predictive value. In terms of cerebrovascular disease, Huang et al. in a prospective cohort study that included 19,924 hypertensive patients, a chronically elevated TyG index was associated with an increased risk of stroke, particularly ischemic stroke37. This finding means that regular monitoring of the TyG index may help to identify individuals with hypertension who are at higher risk of stroke and allow for early intervention. Chen et al. conducted a retrospective study revealing that the TyG index is an independent risk factor and an important predictor of severe disorders of consciousness and all-cause mortality in patients with critical brain diseases17. And Huang et al. and Cai et al. found in their studies respectively that TyG index may have an important role in identifying patients with high all-cause mortality in hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke18,38. In the context of renal disease, Fritz et al. found that the TyG index appeared to be associated with the risk of obesity-associated end-stage renal disease in a population-based prospective cohort study39. Jin et al. noted that the TyG index was associated with the risk of AKI in ICU patients19. Similarly, Yang et al. reported that TyG index was a reliable independent predictor of AKI incidence and adverse renal outcomes in critically ill heart failure patients40.

Several studies have provided evidence that the TyG index can be used as a predictor of contrast-induced and critical cardiac insufficiency in patients with AKI, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension with reduced renal function, but there are limited data specifically for critically ill patients with TBI40,41,42,43. In our study, through in-depth mining and analysis of data from a large cohort in the United States, we analysed the significant linear correlation between TyG index and AKI in patients with severe TBI, implying that the risk of AKI showed a direct and predictable increase with increasing TyG index. This finding provides an important biomarker basis for assessing and managing AKI risk in patients with severe TBI. This finding is an important guideline for clinicians because it reminds us to pay sufficient attention to the metabolic status of patients in addition to the traditional risk factors when assessing the risk of AKI in patients with TBI.

In addition, our study explored possible associations between TyG index and pathophysiological mechanisms of TBI and AKI. The association of IR and TyG index with AKI in patients with severe TBI can be attributed to several potential mechanisms. Firstly, early glucose elevation is prevalent in patients with TBI, even on patients without diabetes, and even more so in critically ill patients44,45, which in turn aggravates the renal burden and increases the risk of AKI. In other previous studies it has been shown that early hyperglycaemia predisposes to a poor prognosis in patients with TBI and is mainly associated with patient mortality46,47,48. There are various mechanisms by which hyperglycaemia occurs in TBI patients, the main mechanism being stress-induced elevation of blood glucose. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis can lead to an increase in the release of substances such as catecholamines and cytokines, which promotes the release of glucose from the liver, including through gluconeogenesis49. The other mechanism contributing to elevated blood glucose is IR, where impairment of the post-insulin receptor binding pathway and down-regulation of Glucose Transporter 4(GLUT-4) promotes peripheral insulin-dependent glucose uptake and leads to reduced glucose utilisation50. Secondly, the inflammatory response is closely associated with IR, and the inflammatory response generated after TBI can directly or indirectly damage the kidney through activation of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines. Studies have shown that elevated plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipid transport proteins associated with IR can lead to renal tubular dysfunction associated with inflammatory response51. In addition, IR patients are usually accompanied by increased oxidative stress, and the production of free radicals can damage renal tubular cells and vascular endothelium, affecting the normal function of the kidney and thus triggering AKI52. Vascular dysfunction is also an important factor, and a high TyG index may reflect vascular endothelial dysfunction, which is common in patients with TBI and can lead to reduced renal blood flow, inadequate perfusion, and an increased risk of AKI. Previous studies have shown that IR leads to reduced nitric oxide synthesis in glomerular endothelial cells53 and that the balance between nitric oxide (NO)-dependent vasodilator effects and insulin endothelin 1-dependent vasoconstrictor effects is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent signalling in the vascular endothelium, respectively. In insulin resistance, pathway-specific impairment of PI3K-dependent signalling may lead to an imbalance between NO production and endothelin-1 secretion and result in endothelial dysfunction54.

Meanwhile, elevated TyG index is associated with abnormalities in lipid metabolism8, and elevated levels of free fatty acids exacerbate renal injury either through direct toxic effects or by affecting energy metabolism and inflammatory responses in the kidney55. In addition, IR and high TyG index affect the renal microcirculation, which can lead to abnormal activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which in turn leads to increased blood pressure and intrarenal vasoconstriction, resulting in insufficient perfusion of renal blood flow and increasing the risk of AKI56,57,58. Neuro-renal axis interactions also play a role, with vagus nerve stimulation reducing renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury, whereas in patients with TBI it may lead to a decrease in renal blood flow and function by affecting acetylcholine59, which may be exacerbated by IR and a high TyG index. Finally, IR affects the kidney indirectly through immunomodulatory effects such as increased inflammatory cell infiltration, which increases the risk of AKI60. These mechanisms interact with each other and together lead to the development of AKI. Future studies should further explore the interaction of these mechanisms and look for possible intervention strategies to reduce the risk of concurrent AKI in patients with TBI.

Study limitations

Of course, there are some limitations to our study. For example, due to limitations in the data sources, we were unable to obtain detailed metabolic parameters for all patients, which may have led to some degree of confounding by confounders, despite the use of multivariate adjustment and subgroup analyses. In addition, our study mainly focused on the assessment of the acute phase, and the impact on long-term prognosis needs to be further explored. The formula for TyG requires fasting for the collection of blood glucose and blood triglycerides, but the mimic database takes a de-identified approach to time, so we had to use blood glucose and triglycerides from the first biochemistry after admission to the ICU. This will have some impact on the results.In response to these limitations, we suggest that future studies should focus more on the importance of real-time monitoring of TyG changes in order to more accurately assess its role in the development of TBI and AKI. Meanwhile, we are preparing to conduct a multicentre, large sample size prospective study our findings and further explore the mechanism of association of TyG index with TBI and AKI.

Conclusion

In summary, our study reveals the importance of TyG index in assessing the risk of AKI in patients with severe TBI. This finding not only enriches our understanding of the pathogenesis of TBI and AKI, but also provides clinicians with a new risk assessment tool and basis for the selection of treatment strategies.

Data availability

The data utilized in this investigation was sourced from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV), which is accessible at the following link: https://mimic-iv.mit.edu. To gain access to the data, one must be an authenticated user, complete the required training, and adhere to the project’s data usage agreement. Any request for access to these datasets should be directed to PhysioNet (https://physionet.org/) with the reference DOI: 10.13026/s6n6-xd98. It is essential to note that the dataset has specific licensing and access restrictions in place.

Abbreviations

- TyG index:

-

Triglyceride-Glucose index

- AKI:

-

Acute Kidney Injury

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- TBI:

-

Traumatic Brain Injury

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- IR:

-

Insulin Resistance

- FBG:

-

Fsting Blood Glucose

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- BIDMC:

-

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- CITI:

-

Cooperative Institutional Training Initiative

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision

- ICD-9:

-

Based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- SQL:

-

Structured Query Language

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

- MBP:

-

Mean Blood Pressure

- Spo2:

-

Oxygen Saturation

- RDW:

-

Red Blood Cell Distribution Width

- BUN:

-

Blood Urea Nitrogen

- WBC:

-

White Blood Cell Count

- PTT:

-

Plasminogen Time

- APSIII:

-

Acute Physiology Score III

- OASIS:

-

Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score

- SAPSII:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Score

- SCr:

-

Serum Creatinine

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- ORs:

-

Odds Ratios

- IDI:

-

Integrated Discriminant Improvement

- NRI:

-

Net Weight Improvement Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- AUC:

-

Area Under the ROC Curve

- HOMA:

-

Homeostatic Model Assessment

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal

- GLUT-4:

-

Glucose Transporter 4

- NO:

-

Nitric Oxide

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent

References

Maas, A. I. R. et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 21, 1004–1060 (2022).

Corral, L. et al. Impact of non-neurological complications in severe traumatic brain injury outcome. Crit. Care 16, R44 (2012).

Moore, E. M., et al. The incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with traumatic brain injury. Renal failure 32(9), 1060–1065 (2010).

Li, N., Wei-Guo, Z., & Wei-Feng, Z. Acute kidney injury in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: implementation of the acute kidney injury network stage system. Neurocritical care 14, 377–381 (2011).

Lim, H. B. & Smith, M. Systemic complications after head injury: a clinical review. Anaesthesia. 62, 474–482 (2007).

Ahmed, M., Sriganesh, K., Vinay, B. & Umamaheswara Rao, G. S. Acute kidney injury in survivors of surgery for severe traumatic brain injury: incidence, risk factors, and outcome from a tertiary neuroscience center in India. Br. J. Neurosurg. 29, 544–548 (2015).

Huet, O. et al. Impact of continuous hypertonic (NaCl 20%) saline solution on renal outcomes after traumatic brain injury (TBI): a post hoc analysis of the COBI trial. Crit. Care. 27, 42 (2023).

Simental-Mendía, L. E., Rodríguez-Morán, M. & Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 299–304 (2008).

Irace, C. et al. Markers of insulin resistance and carotid atherosclerosis. A comparison of the homeostasis model assessment and triglyceride glucose index. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67, 665–672 (2013).

Guerrero-Romero, F. et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 3347–3351 (2010).

Li, J., Ren, L., Chang, C. & Luo, L. Triglyceride-glukose index predicts adverse events in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: a Meta-analysis of Cohort studies. Horm. Metab. Res. 53, 594–601 (2021).

Ding, X., Wang, X., Wu, J., Zhang, M. & Cui, M. Triglyceride–glucose index and the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 76 (2021).

Barzegar, N., Tohidi, M., Hasheminia, M., Azizi, F. & Hadaegh, F. The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on incident cardiovascular events during 16 years of follow-up: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 155 (2020).

Sánchez-Íñigo, L., Navarro-González, D., Fernández-Montero, A., Pastrana-Delgado, J. & Martínez, J. A. The TyG index may predict the development of cardiovascular events. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 46, 189–197 (2016).

Kim, J. A. et al. Triglyceride and glucose index and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 171, 108533 (2021).

Gui, J. et al. Obesity- and lipid-related indices as a predictor of obesity metabolic syndrome in a national cohort study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1073824 (2023).

Chen, T., Qian, Y., & Deng, X. Triglyceride glucose index is a significant predictor of severe disturbance of consciousness and all-cause mortality in critical cerebrovascular disease patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 156 (2023).

Huang, Y., Li, Z. & Yin, X. Triglyceride-glucose index: a novel evaluation tool for all-cause mortality in critically ill hemorrhagic stroke patients-a retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 100 (2024).

Jin, Z. & Zhang, K. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and AKI in ICU patients based on MIMICIV database: a cross-sectional study. Ren. Fail. 45, 2238830 (2023).

Yang, Z., et al. Association between the triglyceride glucose (TyG) index and the risk of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with heart failure: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 232 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. High triglyceride-glucose index in young adulthood is associated with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in later life: insight from the CARDIA study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 155 (2022).

Zhang, R. et al. Independent effects of the triglyceride-glucose index on all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: analysis of the MIMIC-III database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 10 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. Predictive effect of triglyceride-glucose index on clinical events in patients with acute ischemic stroke and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 280 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. Triglyceride glucose index influences platelet reactivity in acute ischemic stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 21, 409 (2021).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10, 1 (2023).

Kellum, J. A., Lameire, N. & KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (part 1). Crit. Care. 17, 204 (2013).

Pencina, M. J., Agostino Sr, D., Agostino, R. B. D. Jr, Vasan, R. S. & R. B. & Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat. Med. 27, 157–172 (2008).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Spoto, B., Pisano, A. & Zoccali, C. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 311, F1087–F1108 (2016).

Yanai, H., Adachi, H., Hakoshima, M. & Katsuyama, H. Molecular Biological and Clinical understanding of the pathophysiology and treatments of Hyperuricemia and its Association with Metabolic Syndrome, Cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9221 (2021).

Korkmaz, N., Kesikburun, S., Atar, M. Ö. & Sabuncu, T. Insulin resistance and related factors in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 192, 1177–1182 (2023).

Bonora, E. et al. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 23, 57–63 (2000).

Unger, G., Benozzi, S. F., Perruzza, F. & Pennacchiotti, G. L. Triglycerides and glucose index: a useful indicator of insulin resistance. Endocrinol. Nutr. 61, 533–540 (2014).

Luo, P. et al. TyG Index performs Better Than HOMA-IR in Chinese type 2 diabetes Mellitus with a BMI < 35 kg/m2: a hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Med. (Kaunas). 58, 876 (2022).

Son, D. H., Lee, H. S., Lee, Y. J., Lee, J. H. & Han, J. H. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose index and HOMA-IR for predicting prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32, 596–604 (2022).

Tahapary, D. L. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 16, 102581 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index trajectory and stroke incidence in patients with hypertension: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 141 (2022).

Cai, W. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with ischemic stroke: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 138 (2023).

Fritz, J. et al. The triglyceride-glucose index and obesity-related risk of end-stage kidney disease in Austrian adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e212612 (2021).

Yang, Z., Gong, H., Kan, F. & Ji, N. Association between the triglyceride glucose (TyG) index and the risk of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with heart failure: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 232 (2023).

Gao, Y. M., Chen, W. J., Deng, Z. L., Shang, Z. & Wang, Y. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1150980 (2023).

Dong, J., Yang, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, L. & Hu, Q. A high triglyceride glucose index is associated with early renal impairment in the hypertensive patients. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1038758 (2022).

Qin, Y. et al. A high triglyceride-glucose index is Associated With contrast-Induced Acute kidney Injury in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 522883 (2020).

van den Berghe, G. et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl. J. Med. 345, 1359–1367 (2001).

Rovlias, A. & Kotsou, S. The influence of hyperglycemia on neurological outcome in patients with severe head injury. Neurosurgery. 46, 335–342 (2000). discussion 342–343.

Jeremitsky, E., Omert, L. A., Dunham, C. M., Wilberger, J. & Rodriguez, A. The impact of hyperglycemia on patients with severe brain injury. J. Trauma. 58, 47–50 (2005).

Pin-On, P., Saringkarinkul, A., Punjasawadwong, Y., Kacha, S. & Wilairat, D. Serum electrolyte imbalance and prognostic factors of postoperative death in adult traumatic brain injury patients: a prospective cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 97, e13081 (2018).

Salim, A. et al. Persistent hyperglycemia in severe traumatic brain injury: an independent predictor of outcome. Am. Surg. 75, 25–29 (2009).

Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 373, 1798–1807 (2009).

Gearhart, M. M. & Parbhoo, S. K. Hyperglycemia in the critically ill patient. AACN Clin. Issues. 17, 50–55 (2006).

Civiletti, F. et al. Acute Tubular Injury is Associated with severe traumatic brain Injury: in Vitro Study on Human tubular epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 9, 6090 (2019).

Jin, Q. et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy: role of polyphenols. Front. Immunol. 14, 1185317 (2023).

Wu, G. & Meininger, C. J. Nitric oxide and vascular insulin resistance. Biofactors. 35, 21–27 (2009).

Muniyappa, R. & Sowers, J. R. Role of insulin resistance in endothelial dysfunction. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 14, 5–12 (2013).

Schrezenmeier, E. V., Barasch, J., Budde, K., Westhoff, T. & Schmidt-Ott, K. M. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury - pathophysiological basis and clinical performance. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 219, 554–572 (2017).

Zhou, M. S., Schulman, I. H. & Zeng, Q. Link between the renin-angiotensin system and insulin resistance: implications for cardiovascular disease. Vasc Med. 17, 330–341 (2012).

Peti-Peterdi, J., Kang, J. J. & Toma, I. Activation of the renal renin-angiotensin system in diabetes–new concepts. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 23, 3047–3049 (2008).

Lambert, G. W., Straznicky, N. E., Lambert, E. A. & Dixon, J. B. Schlaich, M. P. Sympathetic nervous activation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome–causes, consequences and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 126, 159–172 (2010).

Inoue, T. Neuroimmune system-mediated renal protection mechanisms. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 25, 915–924 (2021).

Bolton, C. H., et al. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic renal failure: roles of lipoprotein oxidation and pro‐inflammatory cytokines. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 16(6), 1189–1197 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Qilin Yang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) for helping with the revision. Acknowledgements approved by all authors.

Funding

This study was funded by the Postgraduate Innovation Programme of Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, Anhui Province, China (Byycx23144).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H designed the study. J.H extracted, collected and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.CC.S prepared the tables and figures. Y.X proofread the data. JB.W, Y.F and LL.L reviewed the results and interpreted the data. GS.G provided professional advice on the revision of the manuscript as well as funding for the study. DH.K reviewed and revised the manuscript and funded the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Song, C., Gu, G. et al. Predictive value of triglyceride glucose index in acute kidney injury in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 14, 24522 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75887-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75887-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of baseline and trajectory of triglyceride-glucose index with the incidence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2025)

-

Prognostic value of the Braden scale for short-term mortality in critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury

Scientific Reports (2025)