Abstract

The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of various doses of esketamine on the median effective concentration (EC50) of propofol required for inhibiting body movement during hysteroscopy. Additionally, this research aims to explore the pharmacodynamic interactions between esketamine and propofol. Prospective, double-blind, up-down sequential allocation study. Operating room, post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), and general ward. A total of 90 patients were allocated into three groups in a randomized, double-blinded manner as follows: 0.1 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol intravenous injection (EP0.1) group, 0.2 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol intravenous injection (EP0.2) group, 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol of intravenous injection (EP0.3) group. For the initial patient in each group, the starting effector target concentration of propofol was set at 4 µg/ml. Each patient received an initial intravenous injection of 0.04 mg/kg midazolam, followed by the administration of the appropriate dose of esketamine. Ten seconds after the esketamine injection, propofol was administered intravenously to achieve the target concentration. In accordance with the sequential method principle, the concentration of propofol for the subsequent patient was adjusted based on the response of the previous patient. Effective inhibition of body movement was defined as the absence of any involuntary body movements throughout the entire surgical process. If the previous patient exhibited body movements, the propofol concentration for the next patient was increased by 0.5 µg/ml; conversely, if no movements were observed, it was decreased by 0.5 µg/ml. The up-down sequential allocation method and probit regression were used to calculate the EC50 of propofol. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A) and Depression (HADS-D) score, adverse events, hemodynamic changes, demographic data and clinical characteristics. The EC50 of propofol was 3.849 μg/ml (95% CI: 3.419–4.281) in the EP0.1 group, 3.641 μg/ml (95% CI: 2.807−4.200) in the EP0.2 group, and 3.417 μg/ml (95% CI: 2.845–3.852) in the EP0.3 group. These findings suggest that esketamine can dose-dependently reduce the EC50 of propofol. Esketamine can dose-dependently reduce the EC50 of propofol in hysteroscopy, while concurrently lowering patients’ HADS-A and HADS-D scores 24 h post-operation. It is concluded that the optimal dose of esketamine, when combined with propofol for hysteroscopy, is 0.3 mg/kg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, hysteroscopy has been increasingly recognized for its efficacy in diagnosing and treating gynecological diseases, owing to its advantages such as simple operation, minimal trauma, high safety, and accelerated postoperative recovery1. However, the procedure necessitates cervical dilation and endometrial scraping, leading to moderate or severe pain for the patient. This pain is not only a source of anxiety or tension but also a predominant cause of surgical failure2,3. Currently, propofol combined with opioids represents the most prevalent anesthesia approach for hysteroscopic surgeries4,5. While research has indicated that opioids are effective in ensuring adequate sedation and analgesia, they are also associated with increased risks of hypotension and hypoxemia6. Given these challenges, it becomes imperative to investigate a more effective and safer anesthesia protocol for hysteroscopic procedures.

As an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, esketamine is noted for its sedative and analgesic effects, and it represents a more potent dextrorotatory structure compared to ketamine. Its anesthetic efficacy is reportedly double that of ketamine, boasting higher potency and reduced side effects7,8,9,10. Numerous studies have affirmed esketamine’s safety and feasibility for hysteroscopic procedures11,12. Specifically, Yang et al.11 demonstrated that esketamine, when combined with propofol for hysteroscopy, not only ensures effective analgesia but also exerts minimal impact on patients’ circulatory and respiratory systems. Furthermore, this combination lowers the required dose of propofol, resulting in fewer adverse reactions. However, as the dose of esketamine increases, so too does the incidence of psychiatric adverse reactions7. Consequently, investigating the optimal dose of esketamine for use in hysteroscopic surgery becomes imperative.

Currently, there is a lack of research on the ideal dosage of esketamine combined with propofol for anesthesia in hysteroscopic surgery, including its influence on the EC50 of propofol required to suppress body movement during the procedure. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the effects of varying doses of esketamine on the EC50 of propofol for inhibiting body movement during hysteroscopy. Our goal is to identify the optimal dose of esketamine when used in conjunction with propofol for this type of surgery, thereby contributing to the development of a more effective and efficient anesthesia protocol for hysteroscopy.

Methods

Ethical approval

We initiated a prospective and double-blind study, utilizing an up-down sequential allocation method, to ascertain the EC50 of propofol necessary to prevent body movement, specifically when used in combination with various doses of esketamine. This research was endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (approval number: 2023ER287-1) and secured registration with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (registration number: ChiCTR2200065955, registration date: 09/08/2023). All procedures performed in this study were conducted in accordance with ethical standards of research and the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to inclusion, participants received oral and written information about the observational study and subsequently signed informed consent. The study’s commencement with the first patient occurred on August 10, 2023.

Participants and study design

Study participants were selected based on specific inclusion criteria: individuals scheduled for elective hysteroscopic cervical polypectomy, aged between 18 and 65 years, with18.5 kg/m2 < body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2, and classified under American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status grades I or II, were recruited between August 2023 and October 2023. Exclusion criteria for the study encompass allergic reactions to the drugs being investigated, difficulty in cervical dilatation (specifically, if the duration of cervical dilatation > 5 min)13, existing mental illness, the consumption of painkillers within the 48 h leading up to surgery, severe cardiac conditions, hypertension, intracranial space-occupying lesions or intracranial hypertension, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, significant respiratory diseases, and liver or kidney dysfunction.

Patients were allocated into three distinct groups through the use of computer-generated random numbers. These numbers were inscribed on cards, which were then secured in sealed envelopes and stored in an opaque box. Upon each patient’s entry into the operating room, the anesthesia nurse would select an envelope at random, and proceed to administer the designated test drug in accordance with the group assignment detailed on the envelope. The grouping was determined by the dosage of esketamine combined with propofol, delineated as follows: 0.1 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol (EP0.1) group, 0.2 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol (EP0.2) group, and 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol (EP0.3) group. The anesthesia nurse was responsible for preparing the medication and handing it over to the study’s anesthesiologist. Following the completion of the experiment, the anesthesiologist would relay the collected data back to the statistician. Throughout the duration of the study, both the participants and the investigators tasked with outcome assessments remained unaware of the group assignments.

Anesthesia

Before surgery, all participants were required to observe an 8-hour fast for solid foods and a 6-hour fast for clear liquids. They also abstained from any preoperative medications. Upon their arrival in the operating room, we established upper limb venous access and initiated the continuous intravenous infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution at a rate of 5–10 ml/kg/h. Concurrently, we ensured the continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram (ECG), oxygen saturation, and non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP). Intraoperative oxygen was administered via mask at a flow rate of 3–4 L/min. For the initial patient in each group, the starting effector target concentration of propofol was set at 4 µg/ml. After the surgeon prepared all necessary equipment and materials, each patient received an initial intravenous injection of 0.04 mg/kg midazolam14, followed by the administration of the appropriate dose of esketamine. Ten seconds after the esketamine injection, propofol was administered intravenously to achieve the target concentration. The surgeons began surgery when the patient’s intraoperative Bispectral Index (BIS) value was below 60. In accordance with the sequential method principle15, the concentration of propofol for the subsequent patient was adjusted based on the response of the previous patient. Effective inhibition of body movement was defined as the absence of any involuntary body movements (including those of the trunk, limbs, or head and neck)16 throughout the entire surgical process. If the previous patient exhibited body movements, the propofol concentration for the next patient was increased by 0.5 µg/ml; conversely, if no movements were observed, it was decreased by 0.5 µg/ml. All the operative procedures were performed by the same skilled gynaecologist.

Anesthesia management

The BIS values were targeted to be maintained between 40 and 60. When the BIS value exceeded 60 with accompanying body movement, 0.5 mg/kg of propofol was administered17. If the BIS value stabilized within the range of 40–60 but body movement persisted, 0.5 µg/kg of fentanyl was administered. After each administration of propofol, changes in BIS values were continuously monitored for about 1–2 min to confirm that the BIS stabilized within the target range. If these measures failed to achieve the desired BIS range, additional doses of propofol were administered until the BIS was maintained between 40 and 60. Blood pressure and heart rate were also maintained within 20% of baseline values. When the blood pressure decreased by more than 20% from the baseline value, or systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg, 6 mg of ephedrine was given to restore blood pressure. When the heart rate was < 50 beats per minute, 0.5 mg of atropine was given immediately. All patients maintained autonomous breathing throughout the surgery. In the event of hypoxemia (SpO2 < 95%), the anesthesiologist employs mask-assisted pressure ventilation to enhance oxygenation. Post-surgery, patients were transferred to the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) for monitoring. The postoperative pain was assessed using a 10-point Visual Analogue Scale (VAS: 1 = no pain, 10 = the most severe pain, mild pain is classified as 0–3 points on the scale, moderate pain as 4–6 points, and severe pain ranges from 7 to 10 points). The patient’s VAS score was recorded 30 min after their arrival at the PACU. Should the VAS score > 3, an administration of 0.5 µg/kg[12] fentanyl was provided.

Measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this study is to determine the EC50 of propofol for inhibiting body movement when used in conjunction with various doses of esketamine.

Secondary outcome

General patient information was recorded, including SBP, DBP, and HR, which were measured at critical moments: upon entering the room (T1), immediately after the intravenous injection of esketamine (T2), when propofol reached its target concentration (T3), at the onset of loss of consciousness (T4), when the cervix was dilated (T5), and upon awakening from anesthesia (T6). Additionally, we documented the awakening time (which we defined as the period from ceasing the intravenous propofol infusion to the moment the patient responds to verbal cues by opening their eyes), the duration of surgery, and the patient’s satisfaction 30 min after arrival at the PACU. For assessing satisfaction, a 10 cm horizontal line was utilized on paper, with endpoints labeled as 0 (signifying extreme dissatisfaction) and 10 (indicating complete satisfaction)[18]. Patients were instructed to mark this line based on their personal feelings to denote their level of satisfaction, with the scoring categorized as dissatisfaction (0–3 points), average (4–6 points), and satisfaction (7–10 points). Furthermore, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores were also evaluated 30 min after the patients’ arrival at the PACU. Recorded intraoperative and postoperative 24-hour adverse reactions, including hypotension (clinically, the most commonly used definition of perioperative hypotension is a systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg, mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 60 mmHg, or a decrease in MAP or SBP by more than 20% from baseline, whichever criterion is met first. For this study, SBP < 90 mmHg was selected as the primary criterion19), hypertension (perioperative hypertension is characterized by an increase in blood pressure by more than 30% above baseline17), bradycardia (HR < 50 beats/min), tachycardia, respiratory depression (respiratory rate < 8 breaths/min or SpO2 < 95%), nausea and vomiting, and psychiatric adverse reactions (hallucinations, delirium, etc.). In addition, recorded other metrics, including the dosage of propofol, HADS-A and HADS-D scores both one day before and after surgery (these assessments were completed by psychiatrists specializing in areas relevant to the study), and the use of vasoactive drugs both during and after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Based on the insights from published research20, the up-down sequential allocation method necessitates 20–40 participants to accurately estimate the EC50, with the acquisition of six pairs of sequence reversals deemed adequate for a reliable sample size determination. Consequently, the number of subjects per group was determined to be 30. To facilitate additional validation and sensitivity analysis, probit regression analysis was implemented, scrutinizing the aggregated instances of “effective” and “ineffective” reactions across varying concentration tiers within each group.

Statistical evaluations were conducted using SPSS 26.0 software. For continuous variables following a normal distribution, these were presented as mean ± standard deviation (‾x ± s ). To compare these across different groups, one-way ANOVA was employed, followed by Bonferroni correction for post hoc pairwise analyses. In situations where continuous variables were assessed at several time points within each group, two-way repeated measures ANOVA was utilized, with a subsequent simple effects analysis to investigate any interaction effects between the group and time. For variables that did not follow a normal distribution, the median (M) and interuartile range (IQR) were used for description, with the Kruskal-Wallis H test carried out for group comparisons and Bonferroni correction applied for detailed pairwise comparisons. Categorical data, expressed in percentiles, were analyzed using Pearson’s X2 test or Fisher’s exact test depending on the data distribution. For ordinal variables’ comparisons across groups, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed, whereas the Friedman test was used for analyzing variations within groups, accompanied by Bonferroni correction for refined post hoc pairwise analyses. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05.

Results

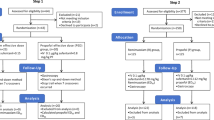

For this study, a total of 98 patients were recruited. However, adjustments were made due to several exclusions: 8 patients were found not to meet the inclusion criteria, two patients declined participation, one was diagnosed with a mental illness, three had taken analgesics within 48 h prior to surgery, and two experienced difficulty in cervical dilatation, as shown in Fig. 1.

Demographic data and clinical characteristics

There were no significant differences in age, ASA grade, weight, height, recovery time, operation time, and vasoactive drug use among the three groups, indicating comparable baseline characteristics. However, a noteworthy distinction emerged when comparing anesthetic satisfaction and postoperative pain between the groups. Specifically, the number of patients in the EP0.3 group who were satisfied with the anesthetic effect increased significantly compared with the EP0.1 and EP0.2 groups (P < 0.01). Similarly, there was a significant rise in the number of patients with mild postoperative VAS scores in the EP0.3 group (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or number. ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; EP0.1: 0.1 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.2: 0.2 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.3: 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; aP<0.05, compared with EP0.1 group; bP<0.05, compared with EP0.2 group.

Median effective concentration

The EC50 of propofol varied across the groups, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The EC50 of propofol was 3.849 µg/ml (95% CI 3.419–4.281) in the EP0.1 group group, 3.641 µg/ml (95% CI 2.807−4.200) in the EP0.2 group, 3.417 µg/ml (95% CI 2.845–3.852) in the EP0.3 group.

Hemodynamics

In the three groups, a clear pattern of systolic blood pressure changes was observed over time. Specifically, when compared to the baseline at T1, the systolic blood pressure at T2−4 and T6 showed a significant reduction (P < 0.05), indicating a notable decrease during these intervals. Conversely, a significant increase in systolic blood pressure was noted at T1−2 and T4−6 when compared with T3 (P < 0.05). Furthermore, compared to T5, the systolic blood pressure at T3−4 and T6 was significantly lower (P < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 3.

In the three groups, analysis of diastolic blood pressure variations reveals distinct patterns. Specifically, when compared with T3, the diastolic blood pressure at T1−2 and T4−6 was significantly higher (P < 0.05), illustrating elevated levels during these periods. Conversely, a significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure was observed at T3−4 and T6 when compared with T5 (P < 0.05). In the EP0.1 and EP0.2 groups, the diastolic blood pressure at T2−4 and T6 showed a significant decrease compared with T1 (P < 0.05). However, in the EP0.3 group, only the diastolic blood pressure at T3 was significantly lower than at T1 (P < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 4.

In the three groups, a detailed examination of heart rate changes demonstrates specific trends over time. Initially, compared with T1, a significant increase in heart rate was observed at T4 (P < 0.05). Additionally, when compared with T3, the heart rate at T4−5 was significantly higher (P < 0.05), further highlighting this period of elevated heart rate. In contrast, the heart rate at T2−3 and T6 was significantly lower when compared with T5 (P < 0.05), suggesting periods of relative heart rate reduction, as depicted in Fig. 5.

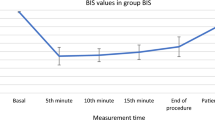

In the three groups, the BIS values at T2−6 were significantly lower than those at T1. However, the BIS values at T1−2 and T6 were higher than those at T3 and T5. Specifically, in the EP0.3 group, the BIS values at T5 were higher than that at T3, while the BIS values at T3−4 were lower than those at T5. Moreover, compared to the EP0.1 and EP0.2 groups, the BIS values in the EP0.3 group were significantly higher at T2−6, as depicted in Fig. 6.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale score

The scores for HADS-A and HADS-D components showed a significant decrease 24 h post-operation compared to pre-operation levels (P < 0.05), demonstrating a notable improvement in both anxiety and depression symptoms among patients. Interestingly, no significant differences were observed in the scores of HADS-A and HADS-D between the three groups either before or 24 h after the operation (P > 0.05), indicating a consistent effect across the board, as shown in Table 2.

HADS-A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety; HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression; EP0.1: 0.1 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.2: 0.2 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.3: 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol.

Side effects

The incidence of psychiatric adverse reactions tachycardia, bradycardia, nausea and vomiting, hypotension, hypertension, and respiratory depression showed no significant differences among the three groups (P > 0.05), indicating a consistent safety profile across all treatments, as shown in Table 3.

EP0.1: 0.1 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.2: 0.2 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol; EP0.3: 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol.

Discussion

This experiment demonstrated that esketamine could dose-dependently reduce the EC50 of propofol required to inhibit body movement during hysteroscopy. Furthermore, it was observed that esketamine significantly lowered patients’ HADS-A and HADS-D scores 24 h post-operation. Notably, in the group receiving an intravenous injection of 0.3 mg/kg esketamine, there was a significant increase in the number of patients reporting satisfactory scores and those with mild postoperative VAS scores, without an associated rise in the incidence of adverse reactions. Based on these findings, a dose of 0.3 mg/kg of esketamine, when combined with propofol for hysteroscopic surgery, is recommended, ensuring efficacy while maintaining safety.

Esketamine, a novel intravenous anesthetic known for its dual effects of analgesia and sedation. Liyuan Ren et al.21 found that intraoperative continuous infusion of esketamine at 0.125 and 0.25 mg/kg/h both increased BIS values, and the higher the dose, the more rapid and significant the increase. This is consistent with our findings, which showed that 0.3 mg/kg esketamine combined with propofol resulted in higher BIS values compared with 0.1 and 0.2 mg/kg esketamine. This may be due to the fact that esketamine triggers an increase in rapid γ-waves22,23. These findings suggest that when applying esketamine anesthesia, patients may experience elevated BIS values despite being at a deep level of anesthesia.

Building on previous research, Hua Yang et al.24 highlighted a significant reduction in the EC50 of propofol for painless gastroscopy in elderly patients. Specifically, when esketamine was combined with propofol at doses of 0.25 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg, the EC50 of propofol decreased by 33.6% and 53.7%, respectively. Echoing these findings, this study revealed that compared to the combination with 0.1 mg/kg esketamine, the EC50 of propofol when combined with 0.2 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg esketamine saw reductions of 5.4% and 11.2%, respectively. These outcomes were in line with the earlier observations, confirming esketamine’s dose-dependent effect in reducing the required dose of propofol. All these findings indicated that intravenous administration of esketamine could effectively reduce the EC50 of propofol. Moreover, it was observed that with an increased dose of esketamine, the EC50 of propofol correspondingly decreased. Consequently, we observed a dose-dependent reduction in the dose of propofol when combined with esketamine. In our study, we found a decrease in the dose of propofol in the combination of 0.3 mg/kg esketamine with propofol compared to 0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg esketamine with propofol. However, the difference was not statistically significant. This may be due to the fact that: (1) The dose gradient of esketamine set up was smaller. (2) The duration of both surgeries was shorter. The underlying mechanisms for this effect include: (1) Noncompetitive antagonism of the NMDA receptor, which inhibits the receptor’s activation by glutamate, thereby diminishing neuronal activity and eliciting analgesic and sedative effects25. (2) Inhibition of the NMDA receptor channels’ opening through noncompetitive antagonism, preventing central sensitization and hyperalgesia26. (3) Action on NMDA receptors leading to the influx of Ca2+ into nerve cells, which activates secondary messengers and results in the production of nitric oxide, prostaglandins, etc., and may also directly inhibit the activity of GABA receptors and reduce presynaptic inhibition27. (4) Impact on voltage-gated sodium channels and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels via NMDA receptors, contributing to its analgesic and sedative effects28. (5) Interaction with opioid receptors, including µ and δ receptors, to produce analgesic effects. These multifaceted actions underscore esketamine’s potential as a powerful adjunct in anesthetic protocols29.

Yongtong Zhan et al.17 observed significant reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as in heart rate, whether induced by propofol alone or by combining propofol with esketamine at doses of 0.05 mg/kg, 0.1 mg/kg, and 0.2 mg/kg in a painless gastroscopy study. These parameters returned to baseline upon exiting the operating room. Similarly, the results of our study indicated a significant reduction in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure when the target concentration of propofol was achieved using 0.1 mg/kg, 0.2 mg/kg, and 0.3 mg/kg of esketamine in combination with propofol. They returned to baseline levels upon cervical dilation, at which point the heart rate peaked. However, Hua Yang et al.24 highlighted that the combination of esketamine and propofol can stabilize hemodynamics, attributing this effect to esketamine’s dose-dependent capability to increase cardiac output and its inhibition of norepinephrine uptake by neurons, which raises the concentration of norepinephrine and induces sympathetic excitation[11]. Consequently, the hemodynamic stability observed in the esketamine combined with propofol group is theoretically more robust. In contrast to Hua Yang et al.‘s findings, the observed reduction in blood pressure in our study could be attributed to the use of a smaller esketamine dose. Additionally, the sympathetic excitatory effect of esketamine may be counteracted by the relatively higher dose of propofol used during surgery. Therefore, it is crucial to monitor circulatory fluctuations in patients when administering low-dose esketamine combined with propofol anesthesia.

In recent years, esketamine has gained significant traction in the treatment of depression, particularly for patients with drug-resistant forms of the condition30,31. It has the capability not only to rapidly ameliorate depressive symptoms but also to substantially mitigate the risk of suicide. Echoing this, Di Qiu et al.32 observed a notable reduction in postoperative HADS-A and HADS-D scores compared to preoperative values. Our findings were in harmony with these observations, showing that the HADS-A and HADS-D scores 24 h post-operation were significantly lower than the preoperative scores (P < 0.05). The antidepressant effect is primarily attributed to the blockade of NMDA receptors and the activation of AMPA receptors, mechanisms that together promote a rapid onset of antidepressant action7.

In our research, respiratory depression occurred in three patients in the EP0.1 group and one patient in the EP0.3 group. However, these incidents were effectively mitigated through face mask pressure ventilation, ensuring that no serious consequences ensued. Our study reveals that patients treated with 0.3 mg/kg of esketamine combined with propofol exhibited significantly higher satisfaction with anesthesia compared to those receiving 0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg of esketamine with propofol. This outcome contrasts with the findings of Hua Yang et al.24, suggesting a notable divergence in patient satisfaction outcomes based on the esketamine dosage used in combination with propofol. This discrepancy could be attributed to the variance in stimulation intensity between hysteroscopy and gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. Hysteroscopy procedures often result in moderate or even severe pain, in contrast to gastrointestinal endoscopies, which typically cause less discomfort. Furthermore, our study revealed a significant increase in the number of patients exhibiting mild postoperative VAS scores when administered 0.3 mg/kg of esketamine in combination with propofol, in comparison to those receiving 0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg of esketamine with propofol. This observation indicates that esketamine demonstrates a dose-dependent analgesic effect across a specified range. In our study, we observed no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions, dosage of propofol, and awakening time across the three groups, with the results showing no statistical significance. This lack of significant findings could be attributed to our small sample size, underscoring the need for more extensive randomized controlled trials in future research endeavors.

There are several limitations in our study that merit attention. First, although the Dixon method enables comparison of different drug effects, it is not primarily intended for studying drug interactions. In future studies, more complex models such as response surface models could be employed to specifically investigate the interactions between propofol and esketamine. Second, the dosages of esketamine used in this study were within anesthetic ranges and relatively low. Considering higher doses, such as 0.4 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg of esketamine, could provide additional insights in future research. Third, midazolam was administered across all groups. Given its sedative properties, midazolam may influence the EC50 of propofol. However, the use of low-dose midazolam was instrumental in mitigating esketamine’s psychiatric side effects33,34,35. Fourth, obese patients are an important candidate group for hysteroscopy, but we excluded them from this study because obesity may affect drug metabolism and distribution. Future studies should include obese patients to verify the applicability of our findings in the obese population. Lastly, our study effectively simulated a realistic anesthesia scenario through bolus-dose administration, but this method resulted in changes in plasma concentration over time. Bolus administration may not provide the stable plasma levels that continuous infusion can achieve. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the effects of different methods of administration on anesthesia outcomes.

Conclusion

Esketamine has been shown to reduce the EC50 of propofol in a dose-dependent manner during hysteroscopy, while concurrently lowering patients’ HADS-A and HADS-D scores 24 h post-operation. Compared to patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg esketamine, those treated with 0.3 mg/kg esketamine in combination with propofol reported significantly higher satisfaction levels with the anesthetic effect. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in the number of patients experiencing mild postoperative pain. Consequently, a dosage of 0.3 mg/kg of esketamine combined with propofol is recommended for optimal anesthesia in hysteroscopic surgery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical reasons, to protect the integrity of the participants, the study data are not publicly available.

References

Fagioli, R. et al. Hysteroscopy in postmenopause: From diagnosis to the management of intrauterine pathologies. Climacteric 23(4), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2020.1754387 (2020).

Riemma, G. et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain relief for office hysteroscopy: An up-to-date review. Climacteric 23(4), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2020.1754388 (2020).

De Silva, P. M., Stevenson, H., Smith, P. P. & Justin, C. T. A systematic review of the effect of type, pressure, and temperature of the distension medium on pain during office hysteroscopy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 28(6), 1148-1159.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2021.01.003 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. ED50 of propofol in combination with low-dose sufentanil for intravenous anaesthesia in hysteroscopy. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 125(5), 460–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13280 (2019).

Ryu, J. H., Kim, J. H., Park, K. S. & Do, S. H. Remifentanil-propofol versus fentanyl-propofol for monitored anesthesia care during hysteroscopy. J. Clin. Anesth. 20(5), 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.12.015 (2008).

Novac, M. B. et al. The perioperative effect of anesthetic drugs on the immune response in total intravenous anesthesia in patients undergoing minimally invasive gynecological surgery. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 62(4), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.47162/RJME.62.4.08 (2021).

Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. Ketamine and Ketamine Metabolite Pharmacology: Insights into Therapeutic Mechanisms [published correction appears in Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Oct;70(4):879]. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(3):621–660. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.117.015198

Himmelseher, S. & Pfenninger, E. Die klinische Anwendung von S-(+)-Ketamin–eine Standortbestimmung [The clinical use of S-(+)-ketamine–a determination of its place]. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 33(12), 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-994851 (1998).

Adams HA, Werner C. Vom Razemat zum Eutomer: (S)-Ketamin. Renaissance einer Substanz? [From the racemate to the eutomer: (S)-ketamine. Renaissance of a substance?]. Anaesthesist. 1997, 46(12):1026–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001010050503

White, P. F. et al. Comparative pharmacology of the ketamine isomers studies in volunteers. Br. J. Anaesth. 57(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/57.2.197 (1985).

Wang, J., Liu, Y. & Xu, Q. Effects of esketamine combined with propofol for hysteroscopy anesthesia on patient hemodynamics and adverse reactions. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 30(1), 18–23 (2024).

Goswami, D. et al. Low-dose ketamine for outpatient hysteroscopy: A prospective, randomised Double-Blind Study. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 48(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.5152/TJAR.2019.73554 (2020).

Tan, H., Lou, A. F., Wu, J. E., Chen, X. Z. & Qian, X. W. Determination of the 50% and 95% effective dose of remimazolam combined with propofol for intravenous sedation during day-surgery hysteroscopy. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther. 17, 1753–1761. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S406514 (2023).

Gurunathan, U. et al. Effect of midazolam in addition to propofol and opiate sedation on the quality of recovery after colonoscopy: A randomized clinical trial. Anesth. Analg. 131(3), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004620 (2020).

Dixon, W. J. Staircase bioassay: The up-and-down method. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 15(1), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80090-9 (1991).

Zhang, X., Li, S., Liu, J. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam besylate versus propofol during hysteroscopy: Single-centre randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in BMC Anesthesiol. 2021 Jun 18;21(1):173]. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021, 21(1):156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01373-y

Zhan, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of subanesthetic doses of esketamine combined with propofol in painless gastrointestinal endoscopy: A prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 22(1), 391. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02467-8 (2022).

Neves, J. F. et al. Sedação para colonoscopia: Ensaio clínico comparando propofol e fentanil associado ou não ao midazolam [Colonoscopy sedation: Clinical trial comparing propofol and fentanyl with or without midazolam]. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol. 66(3), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2014.09.004 (2016).

Sessler, D. I. et al. Perioperative Quality Initiative consensus statement on intraoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 122(5), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.013 (2019).

Pace, N. L. & Stylianou, M. P. Advances in and limitations of up-and-down methodology: A précis of clinical use, study design, and dose estimation in anesthesia research. Anesthesiology 107(1), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000267514.42592.2a (2007).

Ren, L., Yang, J., Li, Y. & Wang, Y. Effect of continuous infusion of different doses of esketamine on the bispectral index during sevoflurane anesthesia: A randomized controlled Trial. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 18, 1727–1741. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S457625 (2024).

Windmann, V. & Koch, S. Intraoperatives neuromonitoring: Elektroenzephalografie [intraoperative neuromonitoring: electroencephalography]. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 56(11–12), 773–780. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1377-8581 (2021).

Nunes, R. R., Cavalcante, S. L. & Franco, S. B. Analgesia postoperatoria: comparación entre la infusióncontinua de anestésico local y opioide vía catéter epidurale infusión continua de anestésico local vía catéter en laherida operatoria [Effects of sedation produced by the association of midazolam and ketamine s(+) on encephalographic variables]. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol. 61(3), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70036-8 (2011).

Yang, H. et al. The median effective concentration of propofol with different doses of esketamine during gastrointestinal endoscopy in elderly patients: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 88(3), 1279–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15072 (2022).

Peltoniemi, M. A., Hagelberg, N. M., Olkkola, K. T. & Saari, T. I. Ketamine: A review of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in anesthesia and pain therapy. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 55(9), 1059–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0383-6 (2016).

Colvin, L. A., Bull, F. & Hales, T. G. Perioperative opioid analgesia-when is enough too much? A review of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. Lancet 393(10180), 1558–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30430-1 (2019).

Lei, Y. et al. Effects of esketamine on acute and chronic pain after thoracoscopy pulmonary surgery under general anesthesia: A multicenter-prospective, randomized, double-blind, and controlled trial. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 8, 693594. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.693594 (2021).

Li, J., Wang, Z., Wang, A. & Wang, Z. Clinical effects of low-dose esketamine for anaesthesia induction in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 47(6), 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13604 (2022).

Shen, J. et al. The effect of low-dose esketamine on pain and post-partum depression after cesarean section: A prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Front. Psychiatry 13, 1038379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1038379 (2023).

Zarate, C. A. Jr. et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63(8), 856–864. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856 (2006).

Murrough, J. W. et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: A two-site randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 170(10), 1134–1142. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392 (2013).

Qiu, D. et al. Effect of intraoperative esketamine infusion on postoperative sleep disturbance after gynecological laparoscopy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 5(12), e2244514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.44514 (2022).

Erk, G., Ornek, D., Dönmez, N. F. & Taşpinar, V. The use of ketamine or ketamine-midazolam for adenotonsillectomy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 71(6), 937–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.03.004 (2007).

Doenicke, A., Kugler, J., Mayer, M., Angster, R., Hoffmann, P. Ketamin-Razemat oder S-(+)-Ketamin und Midazolam. Die Einflüsse auf Vigilanz, Leistung und subjektives Befinden [Ketamine racemate or S-(+)-ketamine and midazolam. The effect on vigilance, efficacy and subjective findings]. Anaesthesist. 1992, 41(10):610–618.

Brecelj, J., Trop, T. K. & Orel, R. Ketamine with and without midazolam for gastrointestinal endoscopies in children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 54(6), 748–752. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31824504af (2012).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X.W. ,S.S.Z and F.J.W. were responsible for the conceptualization and design of this study. They also participated in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, contributing important ideas and key elements to the writing of the paper. Z.Q.W. participated in data collection, analysis, and interpretation.Y.W. participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, supervising and directing the data collection and analysis. N.W. participated in the conception and design of the study, providing significant technical support for the experiment, and participating in data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper and reviewed the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, JX., Zeng, SS., Wu, ZQ. et al. Effect of different doses of esketamine on the median effective concentration of propofol for inhibiting body movement during hysteroscopy. Sci Rep 14, 25153 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75902-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75902-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Analgesic Efficacy of Ketamine/Esketamine Infusion Following Thyroidectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery (2025)