Abstract

Aiming at the difficulty of identification and localization in the detection of contraband targets in X-ray images, as well as the demand for upgrading and deployment of security equipment during the peak flow stage, a lightweight X-ray security contraband detection algorithm is proposed and optimized for YOLOv8. Firstly, the number of channels in the original network is reduced according to a predetermined ratio, which effectively reduces model parameters and computational complexity and achieves better results than the current mainstream lightweight methods, such as model pruning and detection backbone optimization. Secondly, due to the presence of objects of various scales and sizes in X-ray security inspection images, we introduced the BiFPN feature extraction strategy in the neck. We designed a simplified version of BiFPN based on the YOLOv8 network structure to effectively integrate feature information from different levels and scales. Finally, we incorporated the idea of Focal Loss to address the issue of imbalance between positive and negative samples and proposed a new regression loss function, Focal-GIoU Loss, which combines GIoU Loss. This increases the loss weight for important but difficult-to-detect samples, such as small targets and overlapping targets, making the model more focused on these critical samples. Results show that our proposed YOLO-CBF improves mAP by 1.5%, 0.9%, and 0.5% on three datasets with different levels of occlusion in PIDray, while reducing the parameter count and computational cost from the original 3.0M and 8.1G to 2.1M and 6.3G.Moreover, it performs well in comparative experiments between different models and in generalization experiments across different datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increase in crowd density in public transport hubs, X-ray security checks are increasingly important to ensure public safety. X-ray security checks use scanners for non-destructive identification of the contents of the baggage to ensure that the contents do not contain contraband, thus reducing the risk of criminal problems, terrorist activities, invasion of harmful plants and animals, etc.1. The current security means mainly rely on the security personnel to identify and locate the prohibited items based on the color, outline, and other information of the X-ray image, but due to the high uncertainty in the position and angle of stacked items, identifying non-standard planar images is highly challenging. Especially during peak periods of passenger flow, it is difficult for security personnel to quickly identify prohibited items in X-ray images2. Due to these human factors, it is easy to misdetect or omit contraband. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, intelligent security inspection through a machine-assisted workforce is of great significance in improving the efficiency of security personnel3.

Currently widely used in public security inspection is X-ray fluoroscopy technology; the principle of X-ray body imaging is different from general optical imaging; its characteristics and difficulties are (1) the existence of overlapping blocking and complex background interference, X-ray imaging sensors are susceptible to external interference, the background noise is serious, the existence of overlapping blocking between the objects, resulting in the target’s internal structure or details of the blurring, which in turn affects the accuracy of the imaging. (2) Changes in posture and angle: The same object in the X-ray baggage image has changed its shape characteristics significantly with the change in perspective and placement, increasing the difficulty of sample identification and resulting in missed and false detection. (3) Single color: X-ray image of the collected X-ray light intensity using pseudo-color color mapping algorithm, the image color is single, and the lack of rich color information could be more conducive to the analysis and extraction of features. (4) Smaller targets: Some prohibited items account for a small proportion of the entire image, resulting in feature extraction difficulties in the network and making it difficult to identify small targets4.

In response to the above problems, many studies related to them have been conducted. However, these methods have significant shortcomings in real-time, and it is not easy to balance detection speed and accuracy. Therefore, the main goal of this study is to further reduce the equipment cost and increase the detection speed by lightweighting the model in order to better meet the demand for upgrading and deploying security equipment.

Given these considerations, we propose a more lightweight X-ray security inspection prohibited item detection algorithm, YOLO-CBF, which optimizes YOLOv85. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

Effective Reduction in Model Complexity: We reduced the number of channels in the original network according to a predefined ratio, successfully lowering model parameters and computational complexity, thereby improving algorithm efficiency. Compared to current mainstream lightweight methods such as replacing the backbone network or model pruning, our approach is simpler and achieves better lightweighting effects.

-

(2)

Enhanced Feature Extraction with Simplified BiFPN: Due to the presence of objects of various scales and sizes in X-ray security inspection images, we introduced the BiFPN6feature extraction strategy in the neck. We designed a simplified version of BiFPN based on the YOLOv8 network structure to effectively integrate feature information from different levels and scales. Even with the reduced number of channels, BiFPN can still capture and transmit rich feature information, thus enhancing the model’s representation capability and detection performance.

-

(3)

Improved Regression Loss Function: To address the imbalance between positive and negative samples, we introduced the concept of Focal Loss7 and combined it with GIoU Loss8 to propose a new regression loss function, Focal-GIoU Loss. This increases the loss weight for important but difficult-to-detect samples, such as small and overlapping targets, making the model more focused on these samples. This approach compensates for the loss in representation capability caused by lightweighting the model.

Related work

Deep learning-based target detection algorithms can be divided into single-stage and two-stage detection algorithms. Two-stage detection algorithms identify regions containing targets by generating candidate frames and then classify the candidate frames using complex frameworks, focusing on selecting region recommendation strategies for complex frameworks, which are represented by R-CNN9. Based on R-CNN, some excellent target detection models have been gradually developed, such as SPP-Net10, Fast R-CNN11, Mask R-CNN12, and so on. Single-stage detection algorithms, on the other hand, directly detect and classify all spatial regions, focusing on all spatial region suggestions and detecting targets at one time through a relatively simple architecture. Therefore, single-stage detection algorithms can meet the requirements of fast detection and real-time. Representative models include YOLO13 series, SSD14, FSSD15 and so on.

For baggage classification detection of X-ray images, Akcay et al.16 introduced deep learning to the field for the first time in 2016, utilizing transfer learning to apply the AlexNet network to baggage classification in X-ray images.This study showed that deep learning has significant advantages in detection performance and robustness. Subsequently, more studies using deep learning for security contraband detection emerged. Wang et al.17 addressed the issue of occluded prohibited items by designing a Selective Dense Attention Network (SDNet) that learns distinctive features between occluded and non-occluded objects to improve the ability to distinguish occluded items. Gu et al.18 introduced a feature enhancement module in X-ray security inspection images to enhance feature extraction capabilities and obtain target regions through multi-scale fusion, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of prohibited item detection. Zhao et al.19 proposed a Label-Aware mechanism (LA) that establishes relationships between feature channels and different labels, improving the detection accuracy of overlapping prohibited items. These studies focus on detecting small and occluded objects and, although they achieve accuracy improvements, they often require more complex network structures and computational resources, which can pose deployment and efficiency challenges in practical security inspection scenarios.As a result, some researchers have turned to the lightweighting of X-ray security inspection prohibited item detection networks. Gan et al.1 proposed the YOLO-CID model based on the YOLOv7 algorithm, designing an MP-OD in the backbone to enhance the information extraction capability of complex backgrounds and using BiFPN for feature fusion, achieving high detection speeds. Ren et al.20 proposed the LightRay model based on the YOLOv4 algorithm, using the lightweight MobileNetv3 network as the backbone and introducing a shallow feature enhancement network integrating Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) and Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), effectively addressing the detection of small-sized prohibited items in lightweight models.

Although these studies have improved both speed and accuracy, they still impose a significant burden for deployment on some small devices. Moreover, most models lack a particularly outstanding feature, making it difficult to balance speed and accuracy.

To address these issues, we propose a more lightweight and efficient X-ray security inspection prohibited item detection algorithm-YOLO-CBF. In Chapter 4 of this paper, we demonstrate the lightweight advantages of YOLO-CBF through comparative experiments with some current mainstream lightweight methods. We validate the effectiveness of each improvement point through ablation studies. We prove the superiority of YOLO-CBF through comparative experiments with other object detection algorithms. Additionally, we demonstrate its generalization performance through experiments on different datasets.

Method

YOLOv85 adopts a richer gradient flow structure C2f in the backbone network and Neck side, which integrates the high-level features and context information, parallelizes more gradient flow branches, improves the accuracy while lightweight the model, and sets different numbers of channels for other scale models to enhance the overall performance of the model. The Head part adopts the current mainstream decoupled head structure, effectively reducing the number of parameters and computational complexity and improving the generalization ability and robustness of the model. YOLOv8 also abandons the design of using Anchor-Base to predict the position and size of the Anchor box in the previous YOLO series. It uses Anchor-Free to directly predict the center point and aspect ratio of the target, reducing the number of Anchor boxes. Which reduces the number of Anchor boxes, thus further improving the detection speed and accuracy of the model. The network architecture of YOLOv8 is shown in Fig. 1.

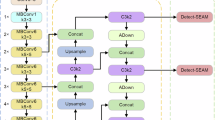

In view of this, we propose a more lightweight X-ray security contraband detection algorithm optimized for YOLOv8. Its overall architecture is shown in Fig. 2.

In the backbone part of the baseline model, we reduce the number of channels in the five feature extraction layers P1-P5 by a specific ratio. In the neck part, we designed a simplified BiFPN structure to replace the original PANet, using the add operation in BiFPN instead of the original concat operation. Additionally, we added a convolution operation before combining with the backbone network features to adapt to the add operation. In the loss part, we introduced the concept of Focal Loss and proposed a new regression loss function, Focal-GIoU Loss, by combining it with GIoU Loss.Next, In Sects. 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3 of this chapter, we provide a detailed explanation of these designs.

Channel simplification

We introduce a straight forward and efficient lightweight approach to deploy large-area target detection networks more effectively in edge computing scenarios. For example, Tinier-YOLO is an improvement of the YOLOv3 network by Fang et al.21, simplifies the computation by reducing the number of channels in the middle layer of the network and using the lightweight Fire Module convolutional module. For the more advanced YOLOv8 model, on the other hand, we adopt a more concise strategy by directly cutting channels in each layer to reduce the model’s computational burden and memory consumption. Specifically, we achieve this simplification by adjusting the width factor \(\alpha\) in the network. The formula for this tuning process is as follows:

Where O represents the number of original channels, r represents the rounding function, and N represents the number of new channels.

The width factor represents the multiplicity factor in the channel dimension; for example, in EfficientNet6 B0, with an initial width factor of 1.0, the number of convolution kernels used in the 3 × 3 convolutional layer of stage1 is 32, while in B6, with a width factor of 1.8, the number of convolution kernels used in the 3 × 3 convolutional layer of stage1 is 32 × 1.8 = 57.6, and to ensure the feasibility of the actual network construction, this result is usually rounded to the nearest integer multiple of 8, i.e., rounded to 56. Increasing the width factor increases the number of channels in the convolutional layer, making the model more complex. In contrast, in the YOLOv8 network, we chose to reduce the width factor, i.e., to shrink the multiplicity of the number of channels, to achieve a lighter model. This approach focuses on simple and feasible channel tailoring to gain a better balance of performance and efficiency on edge devices. This approach maintains the model’s validity while substantially improving the deployability and efficiency in edge computing scenarios.

Simplified BiFPN structure

The neck network of YOLOv8 extends the structure of PANet22 in YOLOv5, as shown in Fig. 3B; the PANet consists of a combination of Feature Pyramid Network23 (Feature Pyramid Network, FPN) and Path Aggregation Network24 (Path Aggregation Network, PAN).The FPN, as illustrated in Fig. 3A, is designed to capture multiple images with varying scales;using this idea can improve the algorithm’s performance and obtain more robust semantic information, but at the same time, it is found that FPN has semantic differences for different layers.

BiFPN is improved on top of FPN, and its structure is shown in Fig. 3C. Compared to PANet, BiFPN adds edges to add contextual information and introduces bidirectional connections between different layers in the middle; these bidirectional connections allow feature information to flow between different levels, which helps to improve communication between different scales and layers, improve the network’s ability to handle targets at different scales and perform feature fusion more effectively.We incorporate the aforementioned feature extraction strategy in the neck and design a simplified version of BiFPN based on the YOLOv8 network structure, as shown in Fig. 4. Specifically, we select the P3, P4, and P5 layers for feature fusion, as these layers contain feature information at different scales, allowing for better integration of multi-scale target features. We add a skip connection in the P4 layer, enabling direct information propagation between different levels, which helps enhance feature representation and improve network training. Additionally, we use the ‘add’ operation in place of the original ‘concat’ operation in the BiFPN structure and introduce a convolution operation before combining with the backbone network features to adapt to the ‘add’ operation. This effectively reduces computational complexity and improves the model’s real-time performance and operational efficiency.

Focal-GIoU loss

The regression loss function used by YOLOv8 is CIoU Loss + DFL, where CIoU is defined as follows:

where IoU is the intersection ratio, b and \(b^{gt}\) denote the centroids of the two rectangular boxes, \(\rho\) denotes the Euclidean distance between the two rectangular boxes, c denotes the diagonal distance between the closed regions of the two rectangular boxes, \(\upsilon\) is used to measure the congruence of the relative proportions of the two rectangular boxes, and \(\alpha\) is the weighting coefficient. \(\upsilon\) and \(\alpha\) are given in the following equations:

where: w, h, \(w^{gt}\), \(h^{gt}\) are the width and height of the labeled box and the real box width and height, respectively.

CIoU has certain defects, and the \(\upsilon\) aspect ratio describes relative values with some ambiguities and does not consider the complex and easy sample balance problem. Additionally, there is an issue of imbalanced training samples in BBox regression. In an image, the number of high-quality anchor boxes with small regression errors is much lower than that of low-quality samples with large errors. Poor-quality samples can generate excessive gradients, impacting the training process. Therefore, to effectively improve the convergence speed of the regression loss, promote the regression of predicted bounding boxes, and further enhance the model’s detection accuracy, we propose a new loss function, Focal-GIoU loss, based on GIoU and combined with Focal loss. From the perspective of gradients, this loss function separates high-quality anchor boxes from low-quality ones. Inspired by Focal-EIoU loss7, this new loss is composed of GIoU loss integrated with Focal loss.

The GIoU formula is as follows:

where \(A^C\) is the area of the smallest outer rectangle of the two rectangles. The GIoU Loss formula is as follows:

The Focal-GIoU Loss formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\gamma\) is a parameter that controls the degree of outlier suppression. The Focal in this loss is somewhat different from the traditional Focal Loss. The standard Focal Loss for the more challenging samples, the more significant the loss, plays the role of difficult samples mining; and according to the above formula, the higher the IoU, the greater the loss, equivalent to the weighting effect, to the better the regression target a more significant loss, which helps to improve regression accuracy.

The GIoU component provides more accurate target localization capabilities, especially when dealing with targets of complex shapes and sizes, by precisely measuring the overlap and inconsistencies between predicted and ground truth boxes. Focal Loss demonstrates excellent performance in handling hard-to-classify samples in object detection tasks, effectively addressing the issue of imbalance between positive and negative samples. Combining the strengths of GIoU and Focal Loss into Focal-GIoU loss enhances the model’s performance in handling complex targets. It increases the loss weight for small and overlapping targets, thereby directing the model’s attention towards these critical yet challenging-to-detect samples.

Experiment and results

Experimental data

The dataset used for the experiments in this paper is the large-scale contraband detection dataset PIDray made public by Wang et al.17, which has 47,677 X-ray images. The dataset has 12 classes of hidden threat items, including baton, pliers, hammer, powerbank, scissors, wrench, gun, bullet, sprayer, handcuffs, knife, and lighter. The distribution of each class is shown in Fig. 5A.The official PIDray dataset is divided into training and test sets in a 6:4 ratio. We believe it is necessary to include a validation set, so we took out 1/10 of the training set to serve as the validation set. Based on the detection difficulty of prohibited items, the test set is composed of three subsets: easy, hard, and hidden. Examples are shown in Fig. 6. The specific quantities of each dataset are detailed in Table 1.

The dataset used for the generalization performance experiments in this paper is CLCXray19. This dataset contains 9565 X-ray images and includes 12 categories, comprising 5 types of knives (blade, dagger, knife, scissors, Swiss army knife) and 7 types of liquid containers (cans, carton drinks, glass bottle, plastic bottle, vacuum cup, spray cans, tin). The distribution of each category is shown in Fig. 5B.The dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio.

Experimental details

In this paper, the experimental equipment CPU is Intel Core i5 3 GHz, running memory 8G, and the server graphics card is NVIDIA Tesla K80. The practical framework is pytorch2.0, python3.8, CUDA11.7.

The experimental settings are basically adopted from the officially recommended parameter settings of YOLOv8: the input image size is 640 × 640, the training phase uses the stochastic gradient descent strategy SGD to optimize the network parameters, the learning rate is set to 0.01, the learning rate momentum is set to 0.937, the weight decay is 0.0005, the number of processes is 8, the batch is 16, and the epoch is 500.

Evaluation indicators

The experiments use the mean average accuracy of recognition for all categories mAP (IoU threshold is taken as 0.5) as an evaluation metric, and its precision (precision, P), recall (recall, R), average precision (AP), mean average precision (mAP) is calculated as:

where TP is the true case, FP is the false positive case, FN is the false negative case, and n is the total number of categories of target detection.

In addition, in the discussion of balancing lightweight with performance, the number of parameters, computation, and detection speed of the model is also a necessary part to be considered, so it is also essential to introduce three parameters of model architecture details, namely the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs), the number of parameters (Params), and the average detection time S per image where S denotes the sum of forward propagation time, model inference time, and NMS time.

Experimental results and analysis

Experiment on channel simplification effects

In the channel simplification experiments, we use different width factors \(\alpha\) (0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, respectively) to censor the channels of YOLOv8n, and in order to detect the lightweight effect, it is compared with the YOLOv8n replaces the light backbone with PP-LCNet25, EfficientNet6, MobileNetV326, FasterNet27, VanillaNet28 models, and YOLOv8n after pruning (retention factor of 0.8, 0.7, 0.6, and 0.5, respectively) for model comparison. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

By analyzing the first half of Table 2, it can be seen that with the reduction of channels, the model shows a significant lightweight effect in the number of parameters and floating point operations, and the overall trend of detection performance is relatively smooth and the moderate lightweight does not significantly damage the detection performance. When the \(\alpha\) is 0.9 and 0.8, a slight increase in accuracy is achieved while lightweighting. Among them, YOLOv8n-\(\alpha\)0.8 shows a more balanced degree of lightweight, remaining at 85.6%, 87.5%, 65.9%mAP@0.5 and improving inference speed while reducing the number of parameters by about 30% and the number of floating-point operations by 20% in the original YOLOv8n model. This allows the model to improve inference efficiency while maintaining high detection performance, providing an attractive alternative for target detection tasks in resource-constrained environments.

Experimental results with trunk replacement, as well as model pruning, show that these lightweight methods fail to achieve a balance between speed and accuracy. Directly simplified channels exhibit higher detection accuracy and relatively low computational cost. For example, YOLOv8n-\(\alpha\)0.7 and PP-LCNet-YOLOv8n show similar lightening effects but with far less accuracy.

Ablation experiment

To verify the effectiveness of the improved network model of YOLOv8 proposed in this paper in the identification of contraband in X-ray security checks, this paper conducts ablation tests on the base network YOLOv8n. The specific test content and results are shown in Table 3 below.

The experiments are based on the YOLOv8n model as a baseline, and the results of the ablation experiments with the introduction of the three modules of channel simplification, BiFPN, and Focal-GIoU Loss, respectively, as well as the combination of the three modules are shown in the table. With the introduction of the channel simplification module, the number of parameters and the number of floating-point operations of the model are significantly reduced, and the accuracy achieves a slight improvement in the easy and hard subsets, which reduces the complexity of the model and reduces the computational burden by deleting the channels and thus improves the operation efficiency of the model to a certain extent; the introduction of BiFPN enables the improvement of the detection accuracy to be achieved in the datasets of various difficulty levels of 1.1%, 1.5%, and 1.0%, respectively, which is attributed to the fact that the module improves the feature pyramid network, enhances the fusion effect of the features, achieves adaptive feature fusion, and improves the efficiency of the information transfer; after the introduction of the Focal-GIoU Loss, there is an improvement of 1.1% and 0.5% in the hard and hidden subsets, respectively, and it maintains the original detection speed. It is believed that this is because Focal-GIoU Loss pays more attention to the misdetected samples when dealing with hard cases, which improves the model’s ability to learn from hard cases. Combined, these three components achieve the desired balance, resulting in mAP improvements of 1.5%, 0.9%, and 0.5%, respectively, while maintaining a lightweight model and increasing detection speed. Overall, the integration of these three modules enhances the model’s performance across various subsets by reducing the number of parameters, optimizing feature fusion, and improving the object detection loss function, all while maintaining a lightweight framework and achieving greater efficiency in detection time.

Comparison with baseline model

In security inspection tasks, false alarms (False Positive, FP) can lead to unnecessary inspection procedures, increasing wait times and inconvenience for both passengers and security personnel, thereby reducing overall inspection efficiency. Missed detections (False Negative, FN) in security inspections may allow objects carrying prohibited items to pass through, leading to security incidents that cause significant losses to personnel and property, and even endangering lives. Therefore, accurate and reliable security systems not only need to control the false alarm rate but also ensure efficient detection capabilities to minimize missed detections. To further analyze and evaluate the model’s performance in security inspection scenarios, Fig. 7 shows the precision-recall curves of YOLO-CBF and the baseline model YOLOv8 on the test subset”hidden”. The PR curve plots precision(P)against recall(R), where higher P indicates fewer false alarms and higher R indicates fewer missed detections. A larger area under the PR curve, or closer proximity to the top-right corner, indicates better detection performance of the algorithm, i.e., the model performs better in controlling false alarms and missed detections.

From the PR curves of both models, we observe that the comprehensive performance represented by the deep blue curve, YOLO-CBF, has a slightly larger area than YOLOv8, indicating an overall improvement in detection performance. For specific categories such as ”Handcuffs” and ”Wrench”, both models’ PR curves approach the top-right corner, indicating excellent detection performance in these categories. For categories like ”Hammer” and ”Powerbank”, YOLO-CBF shows a larger area under the curve, suggesting significant improvement in detection performance for these categories in the enhanced model. These results demonstrate that YOLO-CBF outperforms YOLOv8 in both overall and specific category detection capabilities, thereby increasing mean average precision (mAP) and performing exceptionally well in complex detection tasks.

The heatmap illustrates the areas that the model focuses on, where warmer colors (such as red and yellow) indicate higher attention from the model. Ideally, the highlighted regions in the heatmap should closely overlap with the annotated object locations, which would suggest high accuracy in the model’s detection and classification. In Fig. 8, we present the heatmaps of YOLO-CBF and the baseline model YOLOv8 on several test samples.

From the heatmaps, YOLOv8’s attention to objects appears to be more dispersed. Some attention points are located outside the objects, which could lead to false detections or inaccurate localization. In contrast, YOLO-CBF’s attention areas are more focused and precise, with the highlighted regions in the heatmap being closer to the annotated objects. This suggests that YOLO-CBF is more accurate in localization and recognition, with a lower likelihood of false detections.

To provide a more intuitive comparison of the performance between YOLO-CBF and the baseline model YOLOv8, we extracted partial test results as shown in Fig. 9. As seen in Fig. 9A, YOLOv8 incorrectly detected a non-existent powerbank, whereas YOLO-CBF correctly did not detect it. Similar results are shown in Fig. 9B and C, demonstrating significant improvements in detection confidence and reduction in false positives by our model. This further validates the stability and accuracy of YOLO-CBF.

Comparison with other object detection models

We compared the performance of the YOLO-CBF algorithm with other lightweight object detection algorithms, and the experimental results are shown in Table 4

As shown in Table 5, YOLO-CBF has the smallest parameter count and floating point operations (FLOPs) among all models, with 2.1M parameters and 6.3G FLOPs. In contrast, Yolov3-tiny has the highest parameter count and FLOPs, with 12.1M and 18.9G, respectively. In terms of mAP@0.5% (mean average precision), YOLO-CBF achieved the highest scores across all three datasets (easy, hard, hidden) with 86.9%, 87.8%, and 66.5%, respectively, outperforming or closely matching other models. Regarding detection time, YOLO-CBF demonstrates excellent performance, comparable to the speed of YOLOv5n and YOLOv6n. Although YOLOv6n shows a slightly faster speed, its lightweight effect and accuracy are significantly inferior to YOLO-CBF. Overall, YOLO-CBF maintains a low parameter count and FLOPs while providing outstanding mAP@0.5% scores and achieving detection times on par with other lightweight models, highlighting its advantages as a lightweight object detection algorithm.

Generalization experiment

To verify the generalization effect of YOLO-CBF, we compared the baseline model and YOLO-CBF on the CLCXray test set, and the results are shown in Table 5.

From Table 5, it can be seen that the mAP@0.5 of YOLO-CBF is 0.5% higher than that of YOLOv8, indicating a slight improvement in detection accuracy at an IoU threshold of 0.5. The mAP@0.5:0.95 of YOLO-CBF is 0.2% higher than that of YOLOv8, showing a certain improvement in average precision across different IoU thresholds. The detection time of YOLO-CBF is 0.6ms longer than that of YOLOv8. This phenomenon can be attributed to the higher resolution of the CLCXray dataset, which requires more computational resources and thus increases processing time. Figure 10 shows partial visualization results of the CLCXray test set.

In Fig. 10A, it can be observed that YOLOv8 falsely detected a non-existent spraycans, while YOLO-CBF correctly did not detect it. In Fig. 10B, both models falsely detected a non-existent spraycans, but YOLOv8 had a confidence score as high as 0.71, whereas YOLO-CBF’s confidence score was only 0.37. This shows that YOLO-CBF is relatively more stable, indicating that the YOLO-CBF model has better generalization ability on the CLCXray dataset.

Conclusion

To address the challenges of detecting and locating prohibited items in X-ray images and to meet the demands for upgrading and deploying security inspection equipment during peak times, we propose a more lightweight and efficient X-ray security inspection algorithm: YOLO-CBF.Firstly, we reduced the network channel count according to a predetermined ratio, significantly lowering model parameters and computational complexity. This method is more convenient and efficient compared to current mainstream lightweight methods. Secondly, we introduced a simplified version of the BiFPN feature extraction strategy, which effectively integrates feature information at different levels and scales, enhancing the model’s representational capacity and detection performance. Lastly, to make the model more focused on small and overlapping objects, we proposed Focal-GIoU Loss to improve detection precision and enhance recognition capabilities in complex scenes. Our YOLO-CBF algorithm significantly improves detection efficiency and accuracy compared to the baseline model, achieving mAP improvements of 1.5%, 0.9%, and 0.5% on the PIDray dataset, with a reduction of approximately 30% in parameters and computation.

These enhancements not only improve the computational efficiency of security inspection equipment but also provide a more reliable solution for applications in complex scenarios. Despite the significant advancements in performance and lightweighting with YOLO-CBF, there are still some limitations in practical applications: (1) Dataset Dependency: The model’s generalization performance needs to be verified on more types of X-ray image datasets. (2) Detection Time: YOLO-CBF’s detection time is slightly longer on the CLCXray dataset, likely due to the higher resolution of the CLCXray images, which increases computational resource requirements. Further research is needed to optimize the model’s speed for high-resolution images. (3) Small Object Detection: Although Focal-GIoU Loss enhances the detection performance for small and overlapping objects, there is still room for improvement in the detection accuracy of even smaller and denser objects.

Future research will focus on optimizing model speed and enhancing small object detection to further improve YOLO-CBF’s performance and reliability in practical security inspection applications.

Data availability

The PIDray dataset used in this study is available at [https://github.com/bywang2018/security-dataset], and the CLCXray dataset is available at [https://github.com/GreysonPhoenix/CLCXray].

References

Gan, N. et al. YOLO-CID: Improved YOLOv7 for x-ray contraband image detection. Electronics 12(17), 3636 (2023).

Zentai, G. X-ray imaging for homeland security. Int. J. Signal Imaging Syst. Eng. 3(1), 13–20 (2010).

Wang, W., He, L., Cheng, G., Wen, T. & Tian, Y. Learning from ambiguous labels for x-ray security inspection via weakly supervised correction. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 1–16 (2023).

Rafiei, M., Raitoharju, J. & Iosifidis, A. Computer vision on x-ray data in industrial production and security applications: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 11, 2445–2477 (2023).

Solawetz, J. F. What is YOLOv8? The ultimate guide (2023).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, pp. 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Zhang, Y. F. et al. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 506, 146–157 (2022).

Rezatofighi, H., Tsoi, N., Gwak, J., Sadeghian, A., Reid, I. & Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 658–666 (2019).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 580–587 (2014).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 37(9), 1904–1916 (2015).

Girshick, R. Fast r-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 1440–1448 (2015).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 2961–2969 (2017).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 779–788 (2016).

Liu, W., Anguelov, D., Erhan, D., Szegedy, C., Reed, S., Fu, C. Y. & Berg, A. C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, pp. 21–37 (Springer, 2016).

Li, Z. & Zhou, F. Fssd: Feature fusion single shot multibox detector. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.00960 (2017).

Akçay, S., Kundegorski, M. E., Devereux, M. & Breckon, T. P. Transfer learning using convolutional neural networks for object classification within x-ray baggage security imagery. In 2016 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), pp. 1057–1061 (IEEE, 2016).

Wang, B., Zhang, L., Wen, L., Liu, X. & Wu, Y. Towards real-world prohibited item detection: A large-scale x-ray benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 5412–5421 (2021).

Gu, B., Ge, R., Chen, Y., Luo, L. & Coatrieux, G. Automatic and robust object detection in x-ray baggage inspection using deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68(10), 10248–10257 (2020).

Zhao, C., Zhu, L., Dou, S., Deng, W. & Wang, L. Detecting overlapped objects in x-ray security imagery by a label-aware mechanism. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 17, 998–1009 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Lightray: Lightweight network for prohibited items detection in x-ray images during security inspection. Comput. Electr. Eng. 103, 108283 (2022).

Fang, W., Wang, L. & Ren, P. Tinier-YOLO: A real-time object detection method for constrained environments. IEEE Access 8, 1935–1944 (2019).

Wang, K., Liew, J. H., Zou, Y., Zhou, D. & Feng, J. Panet: Few-shot image semantic segmentation with prototype alignment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 9197–9206 (2019).

Lin, T. Y., Dollár, P., Girshick, R., He, K., Hariharan, B. & Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2117–2125 (2017).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 8759–8768 (2018).

Cui, C., Gao, T., Wei, S., Du, Y., Guo, R., Dong, S., Lu, B., Zhou, Y., Lv, X., Liu, Q., et al. PP-LCNet: A lightweight CPU convolutional neural network. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.15099 (2021).

Howard, A., Sandler, M., Chu, G., Chen, L. C., Chen, B., Tan, M., Wang, W., Zhu, Y., Pang, R., Vasudevan, V., et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 1314–1324 (2019).

Chen, J., Kao, S. H., He, H., Zhuo, W., Wen, S., Lee, C. H. & Chan, S. H. G. Run, don’t walk: Chasing higher flops for faster neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 12021–12031 (2023).

Chen, H., Wang, Y., Guo, J. & Tao, D. Vanillanet: The power of minimalism in deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12972 (2023).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

Simon, M., Amende, K., Kraus, A., Honer, J., Samann, T., Kaulbersch, H., Milz, S. & Michael Gross, H. Complexer-YOLO: Real-time 3d object detection and tracking on semantic point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops (2019).

Li, C., Li, L., Jiang, H., Weng, K., Geng, Y., Li, L., Ke, Z., Li, Q., Cheng, M., Nie, W., et al. Yolov6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.02976 (2022).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 7464–7475 (2023).

Funding

This document is the results of the research project funded by the Science & Technology Development Project of Hangzhou City (Grant Nos: 2022AIZD0056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no confict of interest.

Ethics approval

This declaration is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Y., Xu, C. & Zhang, Y. Research on X-ray security contraband identification technology based on lightweight YOLOv8. Sci Rep 14, 25031 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75932-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75932-x