Abstract

The stress disturbances induced by deep tunnel excavation are a key factor leading to the instability and failure of surrounding rock. To investigate the stress evolution in surrounding rock, this study utilizes a physical simulation system for deep caverns to replicate the actual excavation process of tunnels. The study quantitatively analyzes changes in the magnitude and orientation of surrounding rock stresses, and validates the experimental results through numerical analysis. The study revealed that: (1) In elasto-plastic tests, the trajectories of the principal stress axes at the vault and bottom are symmetrical about the XZ plane, whereas in elastic tests, they exhibit symmetry about the origin. (2) The experimental and numerical simulation results of the principal stress axis evolution at four key monitoring points (vault, shoulder, waist, and bottom) are consistent. Using FLAC3D, the regions between these points were further divided, identifying seven distinct regions of surrounding rock, each characterized primarily by one of the four representative patterns, with the shoulder region acting as a transitional zone. (3) Regardless of whether the surrounding rock is in an elastic or elasto-plastic state, the evolution of the principal stress magnitudes and their angles with the coordinate axes remained entirely consistent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the ongoing advancement of China’s “Strong Transportation Nation” strategy, numerous deep and long tunnels have been constructed, characterized by extreme length, size, depth, and clustering. Unlike shallow rock mass projects, these complex geological and stress environments present new challenges for deep rock mass construction. Accurately describing the strength characteristics and deformation failure patterns of surrounding rock, as well as evaluating and predicting its stability, has become a critical issue that needs to be addressed in deep rock mass engineering.

The excavation of deep and extensive tunnels induces substantial changes in the magnitude and direction of principal stresses. These changes influence fracture modes in the surrounding rock as the tunnel face progresses, often leading to unpredictable catastrophic events. This phenomenon has been documented by researchers worldwide1,2,3,4,5. For instance, Eberhardt et al.6 introduced the concept of principal stress axis rotation through three-dimensional numerical simulations, demonstrating that such rotation alters the direction of crack propagation as the tunnel advances. Diederichs et al.7 extended this work by conducting comparative numerical experiments, finding that principal stress axis rotation resulted in crack propagation being approximately twice as extensive compared to scenarios without rotation, highlighting the significant impact of this rotation on crack development. Similarly, Cui et al.8 investigated how stress axis rotation affects surrounding rock failure, showing its substantial influence on both the depth and direction of initial crack propagation. In addition, Kaiser et al.9 developed a numerical model based on the Winston Lake Mine, demonstrating that principal stress axis rotation leads to crack propagation, joint opening, and induced rock bridge failure. This process ultimately contributes to rock mass degradation due to shear disturbances in pre-existing discontinuities. Furthermore, Zhao et al.10 used numerical simulations to assess the stability of surrounding rock in deep soft rock tunnels, concluding that aligning the tunnel with the maximum horizontal principal stress significantly enhances stability. These studies collectively demonstrate that the principal stress axis deviates differently under varying stress conditions and tunnel geometries11. Li et al.12 integrated model tests with numerical simulations to investigate damage and failure patterns in straight-wall arch tunnels under varying principal stress directions. They found that stress concentrations at the arch roof and floor shear substantially increase the likelihood of shear failure.Huang et al.13 utilizd a numerical model based on the Jinping II Hydropower Station, identified patterns of principal stress axis rotation in circular, arch, and horseshoe-shaped tunnel cross-sections under different geological stress conditions. Zhu et al.14 focusing on the drainage tunnel at Jinping II, applied numerical analysis and crack propagation theory to examine dynamic changes in stress magnitude and direction, as well as crack propagation patterns during tunnel face advancement. Jiang et al.15 employed three-dimensional numerical simulations and physical model tests to propose actual stress paths for surrounding rock during TBM excavation, revealing corresponding damage and failure patterns in circular tunnels.Moreover, Zhao et al.16 combined numerical simulations with field experiments to show that the extent of the plastic zone varies with the magnitude and direction of the minimum principal stress, highlighting its critical role in surrounding rock failure. Wang et al.17 used the embedded strain brick method in physical model tests to correlate failure modes with principal stress axis rotation patterns, finding that changes in the direction of the minimum principal stress are more pronounced and significantly contribute to tunnel deformation and failure.

In summary, while most current studies focus on principal stress axis rotation at specific points in the surrounding rock to analyze the corresponding failure characteristics, there has been limited research on the evolutionary patterns of principal stress axes across the entire surrounding rock mass18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Furthermore, research on the rotation of principal stress axes has primarily focused on numerical simulation methods, with limited validation through physical model experiments. In response to this, the present study addresses the issue of regional evolution patterns of principal stress axes in surrounding rock. A physical simulation system for deep caverns was employed, combined with finite difference method simulation software, to analyze the regular evolution paths of principal stress axes. This analysis reveals the patterns of stress magnitude and orientation evolution in surrounding rock during tunnel excavation and proposes laws governing the principal stresses and rotation angles for seven representative regions around the tunnel. These findings provide a valuable reference for enhancing tunnel stability.

Experimental procedure

Experimental apparatus

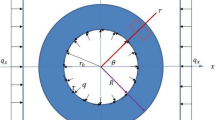

The physical model test apparatus (as shown in Fig. 1) consists of a self-developed deep chamber physical simulation system, a drilling control system, and a data acquisition system. The deep chamber physical simulation system features independent or coupled triaxial stress loading, simulating the real stress conditions of the surrounding rock. It has a maximum load capacity of 8000 kN, with a stability accuracy of ± 0.5%. The force loading rate ranges from 0.17 kN/s to 10 kN/s, while the displacement loading rate varies between 0.001 mm/s and 0.5 mm/s. The hydraulic cylinder has a maximum stroke of 250 mm, and the displacement sensor has a measurement range of 0–300 mm.

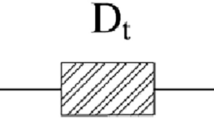

The drilling control system, consisting of a drill bit (with an outer diameter of 110 mm) and a drive system, is used to simulate tunnel excavation. The drilling speed ranges from 0.1 mm/s to 40 mm/s, with a maximum stroke of 1500 mm. The data acquisition system is composed mainly of a computer, a DH5921 dynamic strain acquisition instrument, and stress gauges. Each stress gauge is made of strain bricks with a size of 30 mm (as shown in Fig. 2). On three diagonally adjacent faces, 45° resistance strain gauges are arranged to capture strain in various directions. Using elastic-plastic mechanics theory, the principal stress magnitude and direction at the monitoring locations are calculated based on the strain data by using Matlab.

As shown in Fig. 2,the three-orientation strain gauges on the strain bricks are attached to mutually perpendicular base planes of the strain brick matrix, with strain gauges parallel to the X, Y, Z axes measuring strains εx, εy, εz. Taking the XY plane of the strain brick as an example, the strain at any angle within the same plane of the strain brick can be obtained from the in-plane linear strains εx, εy,and shear strain γxy using the Eq. 1. The strain gauges on the XY plane are oriented at 0°, 45°, and 90°. By substituting these three angles into Eq. 2, the following can be obtained.

Similarly, for the other planes, the stresses in each orientation can be obtained using the generalized Hooke’s law, as given by Eq. 3. Here, εij is the corresponding component of the strain tensor, representing uniaxial elongation in the i-orientation (when i=j) or shear strain between the i and j planes (when i≠j); λ is the Lamé constant, and G is the shear modulus.

The stresses in each orientation can be used to obtain the principal stresses, which are the eigenvalues of the stress matrix, according to the following formula:

To determine the principal stress orientation, it is necessary to further obtain the unit projection components of each principal stress for subsequent analysis. l, m, n are the unit projections of each principal stress on the X, Y, and Z axes (σ1(l1,m1,n1),σ2(l2,m2,n2),σ3(l3,m3,n3)) and obtained from Eq. 5.Using the cosine formula as shown in Eq. 6, calculate the values of l, m, and n corresponding to each angle in FLAC3D, and similarly for σ2 and σ3.

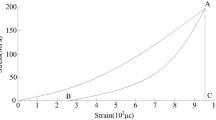

Sample preparation

The preparation of samples in model testing is a critical step for accurately reproducing the tunnel excavation process. Based on previous research and considering the experimental process, M30 cement mortar was selected for sample casting. This mortar exhibits similar granularity and porosity to rock and shares comparable tensile and compressive strengths, as well as brittle failure characteristics. To ensure similarity in mechanical parameters, cylindrical samples measuring 50 mm × 100 mm and 20 mm × 25 mm were prepared with the same mix ratio for uniaxial compression tests, Brazilian splitting tests, and triaxial compression tests, as detailed in Table 1. The results indicate that the properties of the samples cast with this mix closely align with those of actual rock.

Taking into account boundary effects during testing and the dimensions of the borehole, the size of the samples was determined to be 500 mm × 500 mm × 500 mm. To accurately capture the deformation characteristics of the surrounding rock during tunnel excavation, strain gauges were embedded within the samples during preparation. To prevent misalignment, detachment, or damage of the strain gauges during the casting and vibration process, a casting method using a reference plate was ultimately adopted after extensive preliminary testing (as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4). The test content is shown in the appendix. The dimensions of the reference plate were set at 460 mm × 460 mm × 45 mm to avoid forming joints inside the sample that could affect overall strength.

Specifically, the strain gauges were affixed to the reference plate using high-strength adhesive in four directions—0°, 45°, 90°, and 180°—corresponding to the tunnel crown, shoulder, waist, and bottom, respectively. The distances from each strain gauge to the tunnel wall were maintained at 6 mm, 46 mm, and 86 mm, ensuring that all gauges were aligned. The cement mortar was then poured and vibrated using a pneumatic vibrator. Once the surface had set, the samples were removed and cured under standard conditions for 28 days to achieve the desired strength.

Experimental scheme

To replicate the actual load conditions at different depths in real engineering projects and to determine the impact range of tunnel excavation, this model test employed the actual load conditions for shallow and deep-buried tunnels, as shown in Table 2 (with the excavation direction along the Y-axis, the X-axis aligning with the tunnel axis, and the Z-axis perpendicular to the plane). For Scheme 1, the loads were set at 1, 2, and 3 MPa, corresponding to shallow buried elastic state tunnels, while for Scheme 2, the loads were set at 3, 9, and 12 MPa, corresponding to deep-buried tunnels. To ensure the integrity of strain gauges and specimens during loading, a deep cave physical model testing system was used for multi-stage incremental loading in three directions simultaneously, as illustrated in Table 2; Fig. 5. After reaching the target load value, the specimens were allowed to stabilize for 20–25 min to complete their porosity consolidation phase. To simulate the TBM excavation method, an independently developed casing drilling machine was used with a control system speed of 0.2 mm/s and a rotation speed of 200 r/min, ensuring that strain gauges effectively monitored stress state changes throughout the excavation process. The sample dimensions were 500 mm, which is 2.5 times the diameter of the intended tunnel excavation. This setup, verified through multiple simulation calculations, ensures that the boundaries are not affected by the excavation process, accurately reflecting the conditions of actual underground tunnel engineering projects.

Simulation model

According to the experimental loading and measurement point layout, a three-dimensional model and constraints were established using FLAC3D, as shown in Fig. 6. The horizontal direction perpendicular to the tunnel axis is taken as the X-axis, the tunnel axis direction as the Y-axis, and the vertical direction as the Z-axis.The dimensions of the model in the X, Y, and Z directions are all 500 mm, with the maximum principal stress σ1 along the vertical direction and the minimum principal stress σ3 along the horizontal direction perpendicular to the tunnel axis. The entire numerical calculation model uses the Mohr-Coulomb model, with mechanical parameters of the materials referring to the results of indoor mechanical experiments.The main parameters are shown in Table 1.The tunnel is located at the center of the sample, with a diameter of 110 mm.

Results

Analysis of principal stress evolution in physical model experiments

Figures 7 and 8 show the dashed lines representing the variations of the principal stresses along four measurement lines obtained from physical model tests of elastic and elasto-plastic tunnel excavations. The trends of the two types of test results are consistent. Specifically, the evolution patterns of the principal stresses at the crown and invert, as well as at the shoulder and haunch, are identical.

Surrounding rock at the crown and invert

The dashed lines in Figs. 7a and 8a illustrate the changes in principal stress values at the arch top during the tunnel excavation process. To prevent the variation of strain data in strain bricks from influencing the results after loading, when the rock mass is stable, the strain data is zeroed by means of DH5921 dynamic strain data reading software, enabling accurate monitoring of the surrounding rock state during excavation.As shown in Fig. 7a, during the elastic test, the principal stress at the arch top began to change when L = 20 steps. From L = 23 to L = 30 steps, σ1 and σ2 slowly increased to 3.6 MPa and 2.2 MPa, respectively, while σ3 slowly decreased to 0.07 MPa. In the elasto-plastic test (Fig. 8a), from L = 18 to L = 30 steps, σ1 and σ2 increased from 10.5 MPa and 7.2 MPa to 13.8 MPa and 9.7 MPa, respectively, while σ3 remained almost unchanged. As the tunnel face continued to advance, the principal stresses rapidly decreased. In the elastic excavation test, σ1, σ2, and σ3 decreased to 2.3 MPa, 0.6 MPa, and 0.05 MPa, respectively. Subsequently, σ1 slowly increased to 2.4 MPa, which was 0.1 MPa higher than the initial value, while σ2 and σ3 remained stable with no significant fluctuations. In the elasto-plastic test, σ1, σ2, and σ3 decreased to 11.6 MPa, 4.8 MPa, and − 0.9 MPa, respectively, and then remained stable. As the distance between the strain bricks and the tunnel wall increased, the amplitude of principal stress changes rapidly decreased until no significant fluctuations were observed. The variations in the principal stresses at the arch bottom were similar to those at the arch top. However, when the tunnel face reached L = 27 steps, the maximum and minimum principal stress variations in the elastic test were equal to those at the arch top (Fig. 7d). In the elasto-plastic test, the amplitude of variation in the maximum and minimum principal stresses was slightly lower than that at the arch top. This is due to the higher pressure in the upper region of the tunnel compared to the lower part and the greater stress concentration at the arch top, resulting in a larger variation in principal stress at the arch top compared to the arch bottom (Fig. 8d).

When the surrounding rock is in an elastic state during excavation, the pattern at the arch top is shown in Fig. 9e, and Table 3 lists the angles during the stage of rapid change. At step L = 28, the principal stresses show significant rotation. At this point, the σ1 orientation rotates to make angles of 76°, 59°, and 34°with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; the σ2 orientation rotates to make angles of 86°, 41°, and 49°with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and the σ3 orientation rotates to make angles of 88°, 49°, and 41°with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. Ultimately, the major principal stress deviates to the X axis, the intermediate principal stress deviates to the Z axis, and the minor principal stress returns to its initial position. At the arch bottom (as shown in Fig. 9h), at step L = 29, the principal stresses exhibit severe deviations. At this point, the σ1 orientation rotates to make angles of 45°, 69°, and 53° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; the σ2 orientation rotates to make angles of 86°, 41°, and 49°with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and the σ3 orientation rotates to make angles of 91°, 47°, and 43°with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. The magnitude of angle changes at both positions is similar, but the trajectories of the major principal stress at the arch bottom and top are symmetric about the XZ plane, while the intermediate principal stress is symmetric about the XY plane.

During the elastoplastic excavation process, the stress rotation trajectory at the arch top is shown in Fig. 10a. When L < 30 steps, the principal stresses exhibit slight deviations from their initial positions. At step L = 32, the variations in the angles of the major principal stress start to increase, with angles α and β rapidly decreasing and γ increasing. At this point, the σ1 orientation rotates to make angles of 84°, 47°, and 43° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively, while the intermediate and minor principal stresses remain relatively stable. At step L = 34, all principal stresses exhibit significant deviations. During this process, the σ1 orientation rotates to make angles of 4°, 88°, and 88° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; the σ2 orientation rotates to make angles of 87°, 21°, and 69° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and the σ3 orientation rotates to make angles of 88°, 69°, and 21° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. At this stage, σ1 has deviated to the positive X orientation and remains stable during the subsequent face advance, while the intermediate and minor principal stresses fluctuate in the Y and Z orientations. As seen from the figure, after this point, the two principal stresses undergo significant rotation within the YZ plane before returning to the coordinate axis orientations. At the arch bottom, in contrast to the elastic excavation process, the trajectory and stable position of the principal stresses at the bottom remain stable, but the trajectory of the major principal stress is symmetric about the XZ plane, and the intermediate principal stress is symmetric about the XY plane. In Fig. 10h, when L = 32 steps and the principal stresses exhibit significant fluctuations, the σ1 orientation rotates to make angles of 2.6°, 88.6°, and 87.8° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; the σ2 orientation rotates to make angles of 88°, 20°, and 70.3° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and the σ3 orientation rotates to make angles of 88.4°, 67.8°, and 20° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively.

Surrounding rock at the shoulder and waist

As shown by the dashed lines in Figs. 7b, c and 8b, c, at the arch shoulder and waist, both the maximum and minimum principal stresses exhibit an increasing trend, while the reduction in intermediate principal stress is less pronounced compared to the arch top. The increase in maximum principal stress at the arch waist is greater than that at the arch shoulder. In the elastic test, the maximum principal stress at the arch waist is 2.05 times the original stress, and in the elasto-plastic test, it is 2.0 times. During excavation, when the tunnel face reaches L = 24 steps, the amplitude of change in the maximum and minimum principal stresses at the arch shoulder is smaller than that at the arch top, while at the arch waist, it is larger than at the arch top.

During the elastic test, the principal stress at the arch shoulder begins to change at L = 20 steps. From L = 20 to L = 35 steps, σ1 increases slowly to 3.6 MPa, while σ2 decreases slowly to 1 MPa, and σ3 remains almost unchanged throughout the process (Fig. 7b). In the elasto-plastic excavation, from L = 18 to L = 26 steps, σ1 increases from 14.7 MPa to 16 MPa, while σ3 remains unchanged. As the tunnel face continues to advance, the maximum principal stress increases steadily, while the intermediate and minimum principal stresses remain stable (Fig. 8b).

As shown in Figs. 7 and 8b, c, the trend of principal stress changes at the arch shoulder and waist is consistent, but the amplitude of change at the arch waist is significantly greater than at the arch shoulder. Additionally, the amplitude of principal stress changes during the elastic excavation phase is greater than during the elasto-plastic excavation phase. This is due to the redistribution of stress in the surrounding rock, where stress concentration may occur at the arch waist. In the elastic phase, the material has not yet undergone plastic deformation, so the effects of stress concentration are more pronounced, resulting in larger amplitude of stress change. When the material enters the elasto-plastic phase, plastic deformation alleviates stress concentration to some extent, leading to relatively smaller amplitude of stress change.

As shown in Figs. 9f, g and 10f, g, in both of the elastic and elastoplastic states, the principal stresses at the arch shoulder and waist exhibit relatively stable, arc-shaped rotational trajectories between L = 20 and 33 steps, with similar patterns. The rotation at the shoulder is less pronounced, with all angles ranging from 0° to 90°, and the final positions are not aligned with the coordinate axes. At the waist, the intermediate and minor principal stresses undergo a clockwise rotation of 102° in the XY plane and eventually stabilize, with the intermediate principal stress remaining in the negative Y orientation and the minor principal stress in the positive X orientation.

During the elastic excavation phase, the intensity of the principal stress axis rotation at the arch shoulder is significantly less than at the arch top. As shown in Fig. 9f, at L = 23 steps, the stresses start to deviate from the coordinate axes. By L = 33 steps, there is a trend of returning to the coordinate plane. At this point, σ1 rotates to angles of 60°, 85.7°, and 30° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; σ2 rotates to angles of 34°, 68°, and 65° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and σ3 rotates to angles of 73°, 22°, and 76° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively (as shown in Table 4). At the arch waist, which is in the plane of the tunnel axis, the stress state remains stable before the face advances. When the face continues to advance, shear stress appears and rapidly increases, acting on the tunnel axis plane (i.e., the XY plane), causing the intermediate and minor principal stresses to steadily rotate after L = 23 steps. Ultimately, σ2 stabilizes at 15° from the Y axis and σ3 at 11° from the X axis in the XY plane (see Fig. 9g).

As shown in the Figs. 7 and 8, during the elastoplastic excavation phase, the principal stress rotation trajectories at the arch shoulder and waist are consistent with those in the elastic phase. At the arch shoulder, the stress starts to deviate from the coordinate axes at L = 25 steps (see Fig. 10e). By L = 33 steps, there is also a trend of returning to the coordinate plane. As shown in Fig. 10f, g, σ1 rotates to angles of 58°, 87°, and 10° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; σ2 rotates to angles of 31°, 82°, and 81.5° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively; and σ3 rotates to angles of 79°, 16°, and 83.2° with the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. At the arch waist, the major principal stress shows minimal fluctuation, ultimately remaining in the positive Z orientation, while the intermediate and minor principal stresses steadily rotate after L = 25 steps. Ultimately, σ2 stabilizes at 8.3° from the Y axis and σ3 at 11° from the X axis in the XY plane (as shown in Table 5).

Principal stress evolution analysis in numerical simulation

Surrounding rock at the crown and invert

The sudden change in the principal stress occurred within L = 25 steps in the numerical simulation results. After L = 30 steps, the curves of intermediate and minor principal stresses closely converged, while the major principal stress curve significantly rose toward its initial value. Further comparison with experimental results indicates that the trend of principal stress changes at all strain gauges and measurement points is essentially consistent.

At the arch top measurement point during the simulated elastic excavation, when L = 20 steps, the principal stress at the arch top begins to change. Between L = 10 and L = 26 steps, σ1 and σ2 increase slowly to 3.7 MPa and 2.7 MPa, respectively, while σ3 decreases slowly to 0.2 MPa. In the simulated elasto-plastic excavation test, from L = 20 to L = 26 steps, σ1 and σ2 increase from 12 MPa and 9 MPa to 15.1 MPa and 13.2 MPa, respectively, while σ3 decreases to 0.8 MPa. As the tunnel face continues to advance, the major and intermediate principal stresses decrease rapidly, while the minor principal stress remains almost stable. During the simulated elastic excavation, σ1 and σ2 decrease to 2.7 MPa and 0.6 MPa, respectively. Subsequently, σ1 slowly increases to 3 MPa, which is the same as the initial value, while σ2 and σ3 remain stable at 0.5 MPa. In the elasto-plastic test, σ1, σ2, and σ3 decrease to 11 MPa, 1.5 MPa, and 0.7 MPa, respectively, and then increase steadily. Here, σ1 is 0.7 MPa higher than the initial value, while σ2 and σ3 fluctuate around 0.9 MPa.

Therefore, the experimental results and numerical simulation results are quite similar in trend, with only minor discrepancies. Due to the heterogeneous nature of concrete, strain gauge data collection frequency, and load transfer rates, the principal stresses in the sample lag behind the numerical simulation results by 3–5 steps. Additionally, the analysis reveals that from L = 24 steps to L = 33 steps, there is a significant change in the stress state of the surrounding rock. As the tunnel face advances, the intermediate and minor principal stresses drop sharply and remain stable, while the major principal stress slowly increases. Consequently, the stress state at the arch top transitions from triaxial compression state to uniaxial compression state. This rapid stress release during the process may lead to the formation and propagation of internal cracks.

Further analysis of the numerical simulation results, as shown in Figs. 9a, d and 10a, d, reveals that the simulated stress trajectories are almost identical to the experimental stress trajectories, with the final positions being the same.The angles are shown in Table 6. However, due to excavation disturbances and other factors, the simulations complete the major deviation within L = 27–28 steps, while the actual experimental principal stress deviation occurs later with greater data fluctuations.

As shown above, the principal stress angle rotation trajectories at the crown and the base are different, but both the major principal stress trajectories are symmetrical about the XZ plane, and the intermediate principal stress is symmetrical about the XY plane. Additionally, inelastic excavation causes earlier principal stress rotations compared to elastoplastic testing. Therefore, although the crown and base exhibit similar patterns but different trajectories in the two types of tests, the differences in the deviation trajectories of the crown and base are consistent. Hence, it is sufficient to classify only one type of excavation process for regional pattern delineation.

Surrounding rock at the shoulder and waist

In the numerical simulation, there are no abrupt changes in the principal stresses at the arch waist and shoulder. Except for the continuous increase in the major principal stress, the intermediate principal stress decreases significantly at L = 25 steps, and the minor principal stress decreases slightly. In the elastic simulation, the final principal stresses are 4, 1.7, and 1.5 MPa, while in the elastoplastic simulation; they are 24, 5, and 3 MPa, respectively. The variation in principal stresses at the arch shoulder and waist is greater than the test results, but the remaining trends are consistent, indicating that the casing of the drill pipe plays a partial supporting role during excavation.

The Kirsch solution is a mature method for calculating stress distribution in circular tunnels. To further verify the accuracy of the experimental results, the results for the arch waist location were compared with the calculated results. In both elastic and elasto-plastic tests, the major principal stress at the arch waist is approximately 1.7 to 2.8 times the boundary horizontal stress (elastic 2.8, elasto-plastic 1.7, with the arch waist located 0.06D from the right side of the tunnel). Since the Kirsch solution assumes that the material is in a linear elastic, isotropic, and homogeneous state, the experimental results are quite accurate in the elastic test. However, in the elasto-plastic test, the location is still 0.06D from the tunnel wall, and 0.05D falls within the plastic zone, so the measured results are much lower than the elastic state ratio. Nevertheless, the trends in principal stresses in the elasto-plastic simulations and results are unaffected, maintaining consistent trends with elasto-plastic conditions, showing stable increases in major principal stress, decreases in intermediate principal stress, and slight reductions in minor principal stress.

As shown in Figs. 9b, c and 10b, c, the rotation trends of the principal stresses at the arch shoulder and waist are consistent with those on the right side. Additionally, there are no abrupt changes in the rotation at the shoulder and waist, and all principal stresses change gradually, with clear and obvious patterns.Combining the test data, it is evident that the numerical simulation results effectively and regularly reflect the principal stress change trajectories, which are almost identical to the test results. The control over factors such as distance and angle is precise. For the elastoplastic model, a large number of monitoring points can be set up to delineate the regional principal stress axis rotation patterns in the surrounding rock.

Based on the above test result analysis, there is no significant difference between the numerical simulation and the test results. Moreover, the principal stress change trends at the crown, base, shoulder, and waist are similar. Thus, the principal stress patterns in both types of measurement lines are nearly identical. It is only necessary to analyze the spatial rotation trajectories of the principal stresses at each monitoring point to investigate the evolution patterns of the principal stress axes in the surrounding rock.

Comparison of rotation trajectories of unit principal stress between elastic stage test and numerical simulation: (a) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Crown in Tests; (b) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Shoulder in Tests; (c) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Haunch in Tests; (d) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Invert in Tests; (e) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Crown in Simulations; (f) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Shoulder in Simulations; (g) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Haunch in Simulations; (h) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Invert in Simulations.

Comparison of rotation trajectories of unit principal stress in elastic-plastic phase test and numerical simulation: (a) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Crown in Tests; (b) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Shoulder in Tests; (c) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Haunch in Tests; (d) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Invert in Tests; (e) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Crown in Simulations; (f) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Shoulder in Simulations; (g) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Haunch in Simulations; (h) Rotational Trajectory of Principal Stress Axes at the Invert in Simulations.

Discussions

Stress spindle rotation phenomenon

In the early stages of tunnel engineering, the phenomenon of principal stress axis rotation was not observed or mentioned, as tunnels were typically located in shallow underground layers. During tunnel excavation in these shallow layers, the ground stress is relatively low, and most surrounding rock formations can remain stable without support, with almost all rocks stabilizing under supportive conditions. However, with the emergence of numerous deep and long tunnels, characterized by high ground stress levels and complex geological environments, issues such as rock bursts and construction safety problems have become more prevalent, leading to the recognition of principal stress axis rotation. This is because after tunnel excavation, the surrounding rock wall is in an unloading state, causing a redistribution of internal stresses. In the tunnel’s surrounding rock zone, particularly in areas such as the crown, sidewalls, and invert, principal stresses will change, forming stress concentration zones.

When the excavation face approaches the monitoring section, it induces changes in stress at that location, which are particularly pronounced within a certain range of the excavation face. As the excavation progresses, the surrounding rock in front begins to gradually release pre-stress until the stress stabilizes once the excavation face passes through. Based on tunnel engineering experience, the surrounding rock typically stabilizes when the distance from the excavation face is 2–3 times the tunnel diameter. In this experiment, the boundary is set at approximately 4 times the tunnel diameter from the tunnel wall, which is effectively infinite compared to real tunnel engineering scenarios. Consequently, a significant portion of the 2–3 times tunnel diameter influence zone remains relatively stable. Thus, in this study, the concept of the stress mutation zone is used, where the mutation zone represents areas of substantial and large-angle changes in principal stress and its rotation, which are prone to various disaster conditions. Furthermore, as the distance from the surrounding rock to the tunnel center increases, the principal stress and rotation angle tend to stabilize until they return to the original stable ground stress conditions.

Refinement of eegional characteristics

To investigate the damage characteristics caused by the rotation of stress principal axes, previous studies often conducted single-point, single-line measurements at fixed points and areas, which limits the ability to understand the overall rotation patterns of stress principal axes across the entire excavation process.To derive the regional stress principal axis rotation patterns, it is necessary to conduct comprehensive and repeated measurements using numerical simulation methods before and after actual excavation to develop appropriate support measures and reduce accident rates.

Besides the significant differences in the principal stresses and their rotation trajectories at the arch crown and base in elastic and elastoplastic conditions, the results at the arch shoulder and waist are consistent.Therefore, the stress principal axis rotation patterns of tunnel surrounding rock can be roughly classified into four categories: arch crown, shoulder, waist, and base.As previously discussed, the numerical simulation results align with the experimental results. Due to limitations in monitoring methods and sample preparation, this study uses numerical simulation techniques and a bifurcation method to investigate the stress principal axis rotation patterns at different positions within the intervals of the four measurement lines, and further classifies these patterns to explore the regional stress principal axis rotation rules of the monitoring cross-sections.

The four categories of arch crown, shoulder, waist, and base correspond to 90°, 45°, 0°, and − 90° relative to the tunnel’s meridian plane, respectively. The distances in the simulation results are set according to the experimental plan. To further investigate the stress principal axis rotation patterns across the entire cross-section, a large number of monitoring points need to be set up for result screening and adjustment.As previously described, an efficient bifurcation method is used for layout. The results of monitoring points at intermediate angles and distances from the tunnel wall are compared with the four typical rotation patterns at the arch crown, shoulder, waist, and base. Due to the extensive impact range of tunnel excavation, the stress principal axis rotation effects in disturbance zones farther from the tunnel wall are weaker. To accurately identify regions prone to abrupt changes and potential hazards, the areas with significant rock mass changes are used as the basis for classification.

Figure 11 illustrates the stress principal axis rotation at different angles 6 mm from the tunnel for the elastoplastic model. The figure shows that representative angles such as 30°, 60°, 75°, and − 45°, -30° have rotation trajectories symmetrical with respect to the XY plane, while the − 80° rotation trajectory is consistent with the arch base. As the arch crown and base gradually shift towards the arch waist, the fluctuations in the major principal stress decrease and stabilize, while the intermediate and minor principal stresses move closer to the XY plane and rotate in the same direction and angle along the plane. It can be inferred that the rotation trajectories at each point are symmetrical about the horizontal axis of the tunnel. Additionally, during the rotation from the arch base to the arch shoulder, a significant change in trajectory occurs within the 75°-80° range. Therefore, excluding the left-right symmetry of the tunnel, the surrounding rock can be roughly divided into seven representative stress principal axis rotation characteristic zones, which still need further refinement and comparison based on angles and directions.

In summary, 75°-80° and 0°-30° are key angles where significant changes in internal trajectories occur. By comparing these with the four measurement lines and continually applying the bifurcation method, and using 6 mm as the baseline, expanding the range of monitoring points outward, and applying this method again to accurately determine the boundary values of abrupt change and disturbance zones, the regional stress principal axis rotation patterns can be derived.

Regional characteristic patterns

Using the method described above, the regional stress principal axis rotation patterns of the rock mass mutation zones are obtained, as shown in Fig. 12. The length represents the distance extending to the tunnel wall at the indicated angles, and the angle represents the regional range.

The cross-section is divided into seven regions: Zone I representing the arch base, Zone II between the arch base and shoulder, Zone III between the arch shoulder and waist, Zone IV representing the arch waist. The lower half of the cross-section is roughly symmetrical with the upper half, and the left and right parts are identical. The mutation zone ranges within 1.32D-1.44D, consistent with the empirical range for tunnel engineering mutation zones. The ranges between regions are relatively uniform. In regions I, IV, and VII, the stress principal axis rotation characteristics are consistent with the evolution paths of the major stress and its rotation angles at the arch crown, waist, and base. Regions II, III, V, and VI serve as transitional areas around the arch shoulder, with significant differences in the trajectories and magnitudes of the stress principal axes between pairs. Regions III and V show patterns similar to the arch waist, with lower magnitudes of change in principal stresses and final positions close to the coordinate axes. Regions II and VI have patterns similar to those of the arch crown and base, with larger changes in principal stresses, staying within the spaces between the axes. As shown in Figs. 8 and 9, the four measurement line patterns are the most typical, and similar rotational pattern ranges are observed in the lower half of the tunnel surrounding the arch shoulder. The principal stress and its spatial trajectory diagrams indicate that regions I and VII experience severe changes in major principal stress, leading to intense shear failure, while in Region IV, changes in principal stresses near the region are caused by shear stress, making it prone to tensile failure induced by minor principal stresses.

Ruan26 identified that within the range of 0.5-0.8D from the tunnel wall, the evolution of the principal stress axes is severe, and as the distance from the tunnel axis increases, the stress axis region stabilizes. Liu’s27 loading stress, which matches the maximum vertical stress in this study, resulted in the most severe cracking of the crown. Liu28 proposed a rotation angle gradient, defining four zones: high-frequency, mid-frequency, low-frequency, and no-rotation areas, with the principal stress rotation angle reaching a maximum of 90 degrees.Comparative analysis of the research results shows that in this experiment, the area of abrupt change remains within approximately 0.8D from the tunnel wall. Significant abrupt changes in principal stress values and rotation angles occur at the crown and the invert, leading to the most severe damage. Furthermore, the area identified in this study aligns with the high-frequency zone from previous research. Based on the rotation directions and trajectories of the principal stress axes within the high-frequency zone, this zone has been further divided into seven distinct stress axis rotation regions, providing more detailed judgment criteria for practical engineering applications.

Therefore, for tunnel excavation projects, the location of the face, which is the monitoring cross-section position mentioned, can use the obtained principal stress and its rotation angle patterns to determine appropriate support for critical locations based on the tunneling conditions. This approach aims to minimize rock mass damage and safety accidents caused by excavation.

Conclusions

This study investigates the rotation patterns of the principal stress axes at the vault, shoulder, waist, and bottom in elastic and elastoplastic surrounding rocks during tunnel excavation through physical model tests and numerical simulations.The following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

The major principal stress at the tunnel waist exhibits significant variation, while the intermediate principal stress shows the greatest change at the vault and bottom positions.The changes in other stress magnitudes lie between these values.

-

(2)

In both elastic and elastoplastic tests, the trends of principal stress changes are consistent, but the variation magnitude in elastic tests is slightly greater than in elastoplastic tests.The rotational trajectories of the principal stress axes at the vault and bottom positions differ due to the reversible strain in the elastic stage of the surrounding rock, while the rotational trajectories at other positions are consistent.

-

(3)

Both elastic and elastoplastic tests can divide the cross-section of the surrounding rock into seven types of regions based on the evolution patterns of the principal stress axes.The rotational trajectories of the principal stresses in these seven regions are almost symmetrical about the horizontal plane through the tunnel center.

-

(4)

Regardless of whether the surrounding rock is in an elastic or elastoplastic state, for full-face excavation, the range of influence on the principal stress axes in the surrounding rock is approximately one tunnel diameter before and after the excavation face relative to the monitoring section.

-

(5)

Considering the sudden changes in the magnitude and direction of the principal stresses, elastic excavation is located 0.2D behind the monitoring section, while elastoplastic excavation is located 0.5D behind.The stress transmission in the elastic surrounding rock is more sensitive and rapid.

-

(6)

During tunnel excavation, both the magnitude and direction of stresses change, leading to damage in the surrounding rock. The principal stress evolution patterns summarized in this paper indicate that the significant changes in major stress in regions I and VII are likely to trigger severe shear failure, while the stress changes in region IV are primarily driven by shear stress, making tensile failure more likely due to minor stresses. These patterns can accurately predict the stress distribution within the rock mass, allowing for timely adjustments to support structures and construction methods, and can also predict rock mass failure, reducing the occurrence of disasters.

This study primarily relies on physical model experiments to investigate the stress evolution patterns during tunnel excavation, without considering factors such as rock anisotropy, initial stress direction, and rock layer density that affect the principal stress axes.Based on the stress axis evolution patterns presented in this study, we will proceed with the next step of analyzing the various factors affecting the principal stress axes and provide a comprehensive analysis of the regional rotation patterns of the stress axes.

Data availability

Data availabilityAll data generated or analysed during the current study are included in this published article.If you have any questions, please contact Yue Jiang (Email: jywhrsm@163.com).

References

Cai, M. Influence of stress path on tunnel excavation response–Numerical tool selection and modeling strategy. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 23, 618–628 (2008).

Zhang, C., Zhou, H., Feng, X., Xing, L. & Qiu, S. Layered fractures induced by principal stress axes rotation in hard rock during tunnelling. Mater. Res. Innov. 15, s527–s530 (2011).

Zeqi, Z., Qian, S., Yongqiang, Z., Jiguo, L. & Kanglin, S. Study on the characteristics and patterns of excavation disturbance in surrounding rock stress of tunnel. J. Appl. Basic Eng. Sci. 23, 349–358 (2015).

Hui, Z. et al. Key issues and research progress in the development of a rock hollow cylinder torsional shear apparatus. Rock Soil. Mech. 39, 4295–4304 (2018).

Huang, Z., Zhu, W., Liang, J., Lin, J. G. & Jia, R. -z. three-dimensional numerical modelling of shield tunnel lining. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 21, 434 (1997).

Eberhardt, E. Numerical modelling of three-dimension stress rotation ahead of an advancing tunnel face. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 499–518 (2001).

Diederichs, M. S., Kaiser, P. K. & Eberhardt, E. Damage initiation and propagation in hard rock during tunnelling and the influence of near-face stress rotation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 785–812 (2004).

Cui, W. & Wang, N. Principal stress axis rotation and effect on failure model of surrounding rock during tunnelling. Zhongnan Daxue Xuebao Ziran Kexue Ban J. Cent. South Univ. Sci. Technol. 45, 2062–2070 (2014).

Kaiser, P. K., Yazici, S. & Maloney, S. M. Mining-induced stress change and consequences of stress path on excavation stability—A case study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 167–180 (2001).

Zhao, W., Han, L., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Z. & Wang, G. Study on the influence of principal stress on the stability of surrounding rock in deep soft rock roadway. Caikuang Yu Anquan Gongcheng Xuebao J. Min. Saf. Eng. 32, 504–510 (2015).

Kaiser, P. K. and F. V. Incorporation of rockmass relaxation and degradation into empirical stope design. In 97th Annual Meeting (CIM, 1997).

Yuanxin, L., Zheming, Z. & Junli, F. Influence of principal stress direction on surrounding rock stability. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 36, 1908–1914 (2014).

Huang, L. Torsional Shear test Technology and Instrument Development of Hollow Cylinder of large-size rock (University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2019).

Zhu, Z., Sheng, Q., Zhang, Y. & Liu, S. Numerical modeling of stress disturbance characteristics during tunnel excavation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 4508905 (2020).

Jiang, Y., Zhou, H., Lu, J. & Gao, Y. Experimental study of hollow-cylinder sandstone under constant mean stress considering the rotation of principal stress axes. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 3231–3238 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. Analysis of stress evolution characteristics during TBM excavation in deep buried tunnels. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 5177–5194 (2019).

Zhaohui, W., Wang, J. & Yang, S. An ultrasonic-based method for longwall top-coal cavability assessment. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 112, 209–225 (2018).

Yanhai, Z., Jin, Y., Chenhua, Z., Kai, Z. & Huaiguang, X. Characterization of the pressure arch effect in the far-field arch shell of surrounding rock considering principal stress axis deflection. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 43, 1842–1850 (2021).

Dai, C., He, C., Xia, W. & Li, S. Test on the stability of soft rock tunnel with high ground stress field influenced by direction of maximum horizontal principle stress. Xinan Jiaotong Daxue Xuebao J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 53, 303–311 (2018).

Jiang, Y., Zhou, H., Lu, J., Gao, Y. & Li, Z. Strength, deformation, and failure characteristics of hollow cylinder sandstone under axial–torsional tests. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, 296 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Influence of advanced engineering measures on displacement and stress field of surrounding rock in tunnels crossing active strike-slip faults. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 17, 1477–1501 (2023).

Chang, G., Hua, X. Z., Zhang, J. & Li, P. The mechanism of rock mass crack propagation of principal stress rotation in the process of tunnel excavation. Shock Vib. (2021).

He, N. & Zhang, X. Excavation and construction technology of diversion tunnel under complex geological conditions. Appl. Sci. 13, 11538 (2023).

Guo, X., Li, C. & Huo, T. Shapes and formation mechanism of the plastic zone surrounding circular roadway under partial confining stress in deep mining. Geomech. Eng. 25, 509–520 (2021).

Shi, G. & Li, N. Analyses of block deformation characteristics of large underground cavern and its stability under high in-situ stress. Yanshilixue Yu Gongcheng Xuebao Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 28, 2884–2890 (2009).

Ruan, H. et al. Three-dimensional numerical modeling of ground deformation during shield tunneling considering principal stress rotation. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021095 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Soft rock deformation and failure modes under principal stress rotation from roadway excavation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 335 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. An analytical modelling of the rotation of in-situ principal stresses orientation in the vicinity of an underground opening. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 23, 17480930 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42102307) and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX24_1939).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C Y: Software, Writing -original draft. J L: Conceptualization,Methodology. Y J: Writing - review & editing, Supervision. J X: Writing - review & editing. SC: Grammar check. J C: Grammar check & Assist in the experiment. Z Q: Grammar check & Assist in the experiment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, C., Lu, J., Jiang, Y. et al. Influence of tunnel excavation on the magnitude and rotation angle of principal stress in surrounding rock. Sci Rep 14, 25512 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76030-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76030-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Failure mechanisms of energy redistribution in excavation roadways: experimental and numerical investigation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A Geological Approach for the Estimation of the Confined Elastic Modulus of Rock Based on the Hoek–Brown \({{\varvec{m}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) Constant

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025)