Abstract

Due to the development of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging processing technology, image-based identification of endolymphatic hydrops (EH) has played an important role in understanding inner ear illnesses, such as Meniere’s disease or fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss. We segmented the inner ear, consisting of the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals, using a 3D-based deep neural network model for accurate and automated EH volume ratio calculations. We built a dataset of MR cisternography (MRC) and HYDROPS-Mi2 stacks labeled with the segmentation of the perilymph fluid space and endolymph fluid space of the inner ear to devise a 3D segmentation deep neural network model. End-to-end learning was used to segment the perilymph fluid and the endolymph fluid spaces simultaneously using aligned pair data of the MRC and HYDROPS-Mi2 stacks. Consequently, the segmentation performance of the total fluid space and endolymph fluid space had Dice similarity coefficients of 0.9574 and 0.9186, respectively. In addition, the EH volume ratio calculated by experienced otologists and the EH volume ratio value predicted by the proposed deep learning model showed high agreement according to the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Bland–Altman plot analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

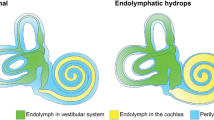

Endolymphatic hydrops (EH) is a pathological anatomical feature in which an increase in endolymphatic volume distends the structures enclosing the endolymphatic space. Only histological evidence from postmortem temporal bone specimens can demonstrate the presence of EH. Hallpike et al.1 and Yamakawa2 were the first to describe this discovery in patients with MD. Hallpike and Cairns regarded hydrops as an essential morbid anatomy of a specific labyrinth disease. EH in the cochlea is often characterized by stretching the Reissner membrane into the scala vestibuli3,4,5. EH may also be caused by excessive endolymph production and impaired endolymph absorption by the endolymphatic sac6,7,8,9. The most common mechanism that can cause EH is the obliteration of the longitudinal flow of the endolymph from the cochlea to the endolymphatic sac. In 1965, Kimura and Schuknecht3 reported that the obliteration of the endolymphatic duct in guinea pigs consistently produced EH.

Image-based identification of EH may be key to understanding inner ear illnesses, such as Meniere’s disease (MD) or fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss. With improvements in imaging technologies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can now be utilized to objectively diagnose EH10. Anatomical segmentation of the inner ear is useful for various tasks, including quantitative image analysis and three-dimensional visualization11,12. The inner ear voxel model obtained through inner ear segmentation helps to understand spatial relationships and morphological changes in the inner ear and helps otolaryngologists plan for more appropriate diagnosis and treatment13.

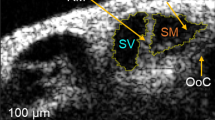

The inner ear, which consists of cochlear tubes, vestibules, and semicircular tubes, is much smaller in volume than other organs and is located in the temporal bone11,14,15,16,17. Segmentation of the inner ear is difficult because the anatomical size of the inner ear is small18, and its structure is complex. In particular, when MRI segmentation of the endolymphatic space is required to prove EH, the size of the endolymphatic space is much smaller and has various shapes. Commonly, the increased volume of the endolymph in HYDROPS-Mi2 appears irregular. Segmentation of the endolymphatic space is very difficult. According to the statistics of the dataset analyzed in the experiment, the volume of the inner ear in MRC and the endolymph in the HYDROPS-Mi2 in whole dataset were 350.81 mm3 and 40.71 mm3 on average, respectively, which is very small compared to the total MRI volume of around 3.235e + 06 mm3. The average volumes of the total fluid space of MRC and endolymph fluid space of Mi2 in the test dataset were 365.41 mm3 and 41.31 mm3, respectively. (eTable 1 in the Supplement 1)

Annotation of the endolymph space required for deep learning is difficult and time-consuming, even for experienced specialists. There are public datasets for various organs, but no inner ear datasets required to calculate the MRI-based EH ratio19,20,21,22,23. With the help of otolaryngologists, we built an MRC stack annotated with the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular regions for the total fluid space and a HYDROPS-Mi2 stack annotated with the endolymphatic fluid space.

Various methods of inner ear segmentation using MRI and CT have been proposed in recent years11. Template-based methods14,24, atlas-based methods16,25,26,27, probability map-based methods27, statistical shape model-based methods11,14,28, deep learning-based methods have been proposed for inner ear segmentation. Inner ear segmentation methods using U-Net, AH-Net, and ResNet models on temporal bone CT images have been proposed12,25,29. Vaidyanathan et al.11 used a 3D U-Net architecture for fully automated segmentation of the inner ear in MRI and obtained a mean DSC of 0.8790. However, obtaining an accurate statistical form in various scenarios requires a large amount of annotation data and processing time28. Also, manual segmentation of the inner ear using specific software requires an experienced specialist with anatomical expertise30,31.

Only recently have a few studies been performed on MRI-based EH ratio calculations predictive of EH, one of the most common pathologies of the total lymphatic space32,33,34. The EH ratio was calculated as the ratio of endolymph fluid space to perilymph fluid space. The EH ratio was estimated using a HYDROPS-Mi2 image, which was generated via pixel-wise multiplication of the HYDROPS image and MR cisternography (MRC) image for a given index slice32,35.

For the standard evaluation of EH using MRI, Nakashima proposed a simple three-stage grading of EH in the vestibule and cochlea10. Recently, 2D network models with VGG, Inception, and U-Net36 as the backbone have been proposed for calculating the EH ratio33,34. These methods do not accurately estimate the EH ratio using only partial and representative slices of the inner ear, and are prone to intra- and inter-specialist variability34,37. The problem of estimating the EH ratio using only representative slices of the inner ear is described in the eFigure 1 in the Supplement 1.

In this study, a single model based on end-to-end 3D U-Net38 was used to analyze the EH volume ratio using 3D medical image features19,20,21. Our method segments the perilymph fluid space and endolymph fluid space simultaneously using the data pair strategy of MRC images and HYDROPS-Mi2 images. In building our models, we fully exploited the fact that the data used for the EH ratio calculation consists of an aligned pair of MRC and HYDROP-Mi2 stacks. The module and source code developed in this work were shared for global research in https://github.com/twyoo/HydropsOTO.

Methods

Data pair strategy

To calculate the EH volume ratio, we needed the number of voxels for the endolymph in HYDROPS-Mi2 and the total fluid space in the MRC. Conventional methods process the segmentation of the total fluid space and endolymph in separate processing steps34. Our proposed method simultaneously processes the segmentation of the total fluid space in the MRC and the endolymphatic fluid space in HYDROPS-Mi2 using a single network model in end-to-end learning. How to concatenate the two stacks is described in the eFigure 2 in the Supplement 1. This method concatenates the cropped MRC volume image and the corresponding HYDROP-Mi2 volume image into one volume image to minimize human intervention and segmentation steps. The concatenated volume image enables end-to-end simultaneous segmentation learning.

Volumetric segmentation framework

The method proposed in Fig. 1 uses a 3D U-Net as a backbone network model. The 3D U-Net inputs in Fig. 1 are the MRC volume image and the corresponding HYDROP-Mi2 volume image. They each have the shape (1 × 24 × 64 × 64), which represents (channels × depth × height × width). If we concatenate this column-wise, the shape will be (1 × 24 × 64 × 128), and if we concatenate it channel-wise, the shape of the volume image will be (2 × 24 × 64 × 64). In this study, we used channel-wise concatenation to improve learning time and performance. The 3D U-Net38 architecture is very similar to U-Net36 and consists of an analysis path and a synthesis path. In the analysis path, each layer contained two 3 × 3 × 3 convolutions, each followed by a ReLU, and then a 2 × 2 × 2 max pooling with a stride of two in each dimension. In the synthesis path, each layer consists of an up-convolution of 2 × 2 × 2 by two strides in each dimension, followed by two 3 × 3 × 3 convolutions, each followed by a ReLU. Skip connections from layers of equal resolution in the analysis path provide high-resolution features for the synthesis path38. In 3D U-Net, both the input and output are in the form of 3D volumes. This means that using 3D information from 3D MRI can take full advantage of the spatial information.

Training method

The proposed 3D-based network model was implemented in 3D using PyTorch software. The training network model was optimized by the AdamW optimizer39 with a weight decay of 0.1 and a momentum of 0.9 to avoid overfitting. The total fluid space and endolymphatic fluid space of the inner ear occupy a very small area in the full image. We used a generalized focus loss function based on the Tversky index for dealing with class imbalances in image segmentation problems40,41,42. We split the dataset into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%), and randomly selected a validation set (20%) from the training set. The learning rate was initially set to 0.0001, and training was performed while changing the learning rate without using a fixed learning rate during the network model training. We reduced the learning rate to 10% of the current value every 20 epochs using step decay method. We trained the model for 100 epochs and evaluated its performance on the validation set at every epoch using the DSC and IOU as metrics. The model that achieved the highest DSC in the validation set was selected as the final model for the evaluation of the test set. The training batch size was set to eight. The input image was cropped to a uniform size of 24 × 64 × 64 for the region of interest (ROI). The cropped image also has a voxel size of 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.0 mm³. Cropping was done before data augmentation. The range of image intensity was normalized from [0.0, 255.0] to [0.0, 1.0]. The translations, rotations, flips, and intensities of the data were used to augment the training data.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

JBNU dataset

MRI data from 129 patients (58 males, 71 females; mean age = 51.2 years old, age range = 18–86 years) were evaluated in this study. MRIs were performed on 53 patients with dizziness and 76 with hearing loss, from a total of 129 patients. A total of 130 ears were used in the analysis, with 67 and 63 right and left ears, respectively. All subjects underwent IV-Gd inner ear MRI from September 5, 2018, to April 13, 2022. The MRI procedure described below was the same as that reported by43. Using a 32-channel array head coil, IV-Gd inner ear MRI was carried out on a 3.0-T machine (MAGNETOM Skyra; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Before having an MRI, all patients had to wait 4 h after receiving a single dosage of gadobutrol (gadolinium-DO3A-butriol, GADOVIST 1.0; Schering, Berlin, Germany). hT2W-3D-FLAIR with an inversion time of 2250 msec (positive perilymph image, PPI), and hT2W-3D-IR with an inversion time of 2050 msec (positive endolymph image, PEI) were performed on all patients to provide anatomical reference for the total endolymphatic fluid. The voxel size was 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.0 mm3, the repetition time was 9000 msec, the echo time was 540 msec.

To assist comparisons, MRC, PPI, and PEI used similar fields of view, matrix sizes, and slice thicknesses, with the exception that PEI had an inversion time of 2050 msec. On the scanner console, we created HYDROPS images by deducting PEI from PPI. By multiplying the HYDROPS and MRC images, HYDROPS-Mi2 images were created using MATLAB (version R2022a 64-bit; MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) to improve the contrast-to-noise ratio of the HYDROPS images.

Two otologists independently evaluated the MRI. Each physician manually drew a contour of the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals on the MRC for total fluid space and HYDROPS-Mi2 for endolymphatic fluid space using ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0; http://www.itk-snap.org). Because the endolymphatic space has a very small volume, segmentation was performed as detailed below to ensure precise segmentation. First, a contour of the total fluid space was drawn using the MRC image to create a label, and the HYDROPS-Mi2 image was superimposed on the created total fluid space label to draw a contour of the endolymphatic fluid space. The EH volume ratio was calculated by dividing the volume of the endolymphatic space in the HYDROPS-Mi2 stack by that of the total fluid space in the MRC stack (EH volume ratio item in the eTable 1 in the Supplement 1). The volume in MRI imaging is typically calculated by multiplying the number of voxels by the voxel size.

Our dataset was built using 130 sets of MRC images and HYDROPS-Mi2 images. MRC images were DICOM files with a spatial resolution of 384 × 324 × 104 with voxel spacings [0.5, 0.5, and 1]. The HYDROP-Mi2 stack was a neuroimaging informatics technology initiative file with the same spatial resolution and voxel spacing as the MRC stack. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeonbuk National University (approval number: 2022-10-039).

The average volumes of the total fluid space of MRC and endolymph fluid space of Mi2 in whole dataset were 350.81 mm3 and 40.71 mm3, respectively, indicating a significantly smaller volume than other organs. Small datasets are a common problem when supervised deep learning methods are used for medical image segmentation, and we used data augmentation as a solution. The dataset was augmented with 132,707 sets using translation, rotation, flip, and intensity changes as an augmented technique and used as training data. The test data used in the experiments are described in the eTable 1 in the Supplement 1.

Metrics

We used the DSC and IOU to evaluate the model performance quantitatively. We analyzed the error ratio and agreement between the EH ratio calculated from the ground truth predicted by the deep learning model using the mean absolute error (MAE), ICC, and Brand-Altman plot. ICC is a commonly used index to evaluate repeatability and reproducibility, and it is an estimate of the portion caused by inter-individual variation among the total variation of measured values44. The Bland-Altman plot is widely used to evaluate the agreement of data measured by two methods of the same variable, is very useful in determining the degree of bias, presence or absence of outliers, and trends, and can calculate the confidence interval of bias45. The Bland-Atman plot consists of a scatterplot with the mean and difference calculated for each pair of measurements from two sets of measurements on the same subject; the mean is the X-axis, and the difference is the Y-axis.

3D segmentation

We segmented the total fluid space of the inner ear, consisting of the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals in the MRC stack and the endolymph fluid space in the HYDROPS-Mi2 stack, using 3D U-Net as the backbone. The results of the experiment show that the 3D model with data pairing showed the best performance. The segmentation performance of the total fluid space had a dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 0.9574 and an intersection of union (IOU) of 0.9186, and the segmentation performance of the endolymph fluid space had a DSC of 0.8400 and IOU of 0.7280. The EH volume ratio was calculated from the segmentation results of the total fluid space of the MRC stack and the endolymph fluid space of the HYDROPS-Mi2 stack. The MAE between the EH volume ratio predicted using 3D U-Net and the 3D-based ground truth is 0.0146.

We performed experiments under various conditions. First, we used the experimental conditions in reference34 to ensure the same experimental conditions. Second, we performed segmentation of single-task U-Net models without data-pairing. Third, we experimented with U-Net based models with data-pairing. We used channel-wise concatenation as the data-pairing method. Finally, we experimented with models with data-pairing and various attention mechanisms added to 3D U-Net models.

The 2D-based deep learning model proposed by Park et al. (2021) calculates the EH ratio only for the cochlea and vestibule regions, not the entire inner ear region. The 2D-based deep learning model used in the first step is trained with a structure in which three consecutive MRC image slices selected as representative by a heuristic rule are independently input into three contracting paths. It processes the MRC image and HYDROPS-Mi2 image through a two-step process. In the first step, the cochlea and vestibule regions are segmented in the MRC stack. In the next step, the endolymph is segmented in the HYDROPS-Mi2 image using the mask decided in the first step. Table 1 below shows the experimental results.

The method of34 does not accurately estimate the EH ratio using only partial and representative slices of the inner ear, and is prone to intra- and inter-specialist variability34,37. The problem of estimating the EH ratio using only representative slices of the inner ear is described in the eFigure 1 in the Supplement 1.

As shown in the experimental results in Table 2 above, the performance of 3D models is higher than that of 2D models. The performance of models with data pairing is better than that of models without data pairing. That is, the 3D model with data pairing has the best performance.

Additionally, we experimented with the Squeeze and Excite (SE) module46, the Attention module47, and the Attention 3D U-Net48 as attention mechanisms. We added only the attention modules listed in Table 3 to the 3D U-Net network model, testing all configurations under the same experimental conditions. Table 3 below shows the experimental results.

As shown in Table 3, our method with the Attention 3D U-Net48 performs the best, while our method without attention mechanisms ranks second. Our method with the Attention 3D U-Net48 includes an attention module with multiple skip connections. Our method requires about 48 h to train and has 2,512,930 parameters. Models46,47 have similar training times and parameter counts to our method. However, our method with the Attention 3D U-Net48 takes approximately 110 h and 25 min to train, with 90,657,774 parameters. This means its training time is about 2.3 times longer, and it has about 36 times more parameters. The large number of parameters increases computational demands and costs due to the need for high-performance hardware.

We chose one sample from the right ear images and presented the segmentation results in Fig. 2. The sample consisted of an MRC stack and an HYDROP-Mi2 stack. The stack of the right ear had 13 consecutive slices. For display purposes, eight slices in the middle were chosen and illustrated in the figures. Figure 2(a) and (b) show the ground truth of the total fluid space and endolymphatic space for the right ear. In addition, Fig. 2(c) shows the EH overlaid with Fig. 2(a) and (b), whereas Fig. 2(d) shows the EH segmented by our method. The real numbers under each slice in Fig. 2(c) show the volume ratio of the ground truth of the fluid space to the endolymph space in each slice in Fig. 2(a) and 2(b). The real numbers under each slice in Fig. 2(d) show the volume ratio of the fluid space and endolymph space in each slice segmented by our method. The averages of the real numbers in Fig. 2(c) and (d) were 0.1702 and 0.2352, respectively. A closer look at each slice of Fig. 2(d) shows that our model segmented the regions very closely to the ground truth of Fig. 2(c). Figure 3 shows the labels and segmentation results of Fig. 2 in 3D. Figure 3(a) and (c) show the ground truth (GT) of the total fluid space and endolymphatic space in three dimensions. Figure 3(b) and (d) show the segmentation results by our method in 3D.

As a result of the experiment, the ICC value of our method was 0.951, indicating a value close to 1, indicating a high degree of agreement (Fig. 4). The ICC had a value between 0 and 1, and the closer the value is to 1, the higher is the degree of agreement. Figure 4 shows a scatter plot between the ground truth and predicted value. The Bland-Altman plot in Fig. 5 shows the degree of agreement between the GT value and the predicted value of the EH volume ratio. The horizontal lines above and below the mean difference line indicate the upper and lower limits of 95%, respectively. The lower limits of agreement (LOA) were [-0.041, 0.041] in Fig. 5.

Discussion

EH is a pathological anatomical feature in which an increase in endolymphatic volume distends the structures enclosing the endolymphatic space. Because histological confirmation of EH is impossible in living patients with related diseases, the accumulation of cases in which correlations have been made between EH imaging (EHI) findings and clinical symptoms, as well as with results from various conventional functional ontological tests, is critical. EH has been estimated using functional tests such as electrocochleography, glycerol test, and vestibular-evoked myogenic potential. However, the precise relationship between the results of these functional tests and endolymphatic volume remains unclear.

Recently, analysis of EH via inner ear MRI in patients has been attempted in a number of studies. Although imaging of EH has not been thoroughly established, image-based identification of EH may be important in understanding inner ear illnesses, such as MD or fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss. For EHI to be used more widely, easier, standardized, and more reliable evaluation strategies must be developed. If possible, EHI may be included in the EH diagnostic guidelines.

The total fluid and endolymph fluid space in the MRC and HYDROPS-Mi2 stacks are very small. Moreover, the endolymph fluid space has an irregular shape. These data features make it difficult for doctors to calculate and determine the EH volume ratio, whether it is manual or semi-automatic. In particular, it requires a lot of time and effort to build the annotation dataset of the deep learning model.

We built the MRC and HYDROPS-Mi2 stack datasets with annotated perilymph and endolymph fluid spaces to accurately calculate the EH volume ratio. In addition, the EH volume ratio calculation was automated by proposing an end-to-end learning network model using a 3D data pair strategy. As a result of the experiment, the perilymph segmentation performance had a DSC of 0.9574 and IOU of 0.9186, and the endolymph segmentation performance had a DSC of 0.8400 and IOU of 0.7280. The EH volume ratio calculated by the doctors and the EH volume ratio value predicted by the proposed deep learning model showed high agreement through the ICC and Bland-Altman plot analysis. Our 3D segmentation approach using column-wise concatenated volume images consumes about 11.54 ms as inference time The diagnosis of inner ear diseases, such as Meniere’s disease or fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss, does not need to be determined in real time by an otologist, which means that our EH ratio calculation does not need to be in real time.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the annotated datasets were small. A training dataset was obtained using the data augmentation technique; however, the performance should be improved by adding a dataset. Second, we used only the 3D U-Net-based models as the segmentation backbone. Additional experiments with various 3D segmentation models are required to achieve a higher segmentation performance. Furthermore, a comparative study with a transformer-based model49,50,51 and a diffusion-based model52,53, which has recently made significant progress in the field of image segmentation, is required. Third, further work is needed to verify the generalizability of the proposed method and to apply it to clinical practice. To generalize the proposed model, training using various modalities is necessary. Additionally, a graphical user interface needs to be developed for clinical usability by otolaryngologists. Once these steps are completed, this technology can significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of diagnosing diseases such as Meniere’s disease, delayed endolymphatic hydrops and sudden low frequency hearing loss, ultimately improving patient care.

Conclusion

In this study, we built an MRC stack and an HYDROP-Mi2 stack annotated with a small irregular fluid space in the inner ear. The annotated dataset has significant clinical value. We proposed a 3D U-Net model with end-to-end learning using a data pair strategy. We conducted various experiments using 2D U-Net, 3D U-Net, and nnU-Net as backbones. As shown by the experimental results, the performance of the 3D model is superior to that of the 2D model. Additionally, the performance of the model with data pairing is better than that of the model without data pairing. In other words, the 3D model with data pairing shows the best performance. In the future, the proposed technology will need to be deployed as part of the medical decision-making process so that its effectiveness can be further evaluated.

References

Hallpike, C. S. & Cairns, H. W. B. Observations of the pathology of Menie`re’s syndrome. Proc. R Soc. Med. 31, 1317–1336 (1938).

Yamakawa, K. U¨ ber die pathologische Vera¨nderung beieinem M_enie`re-Kranken. Proceedings of 42nd Annual Meeting Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Soc Japan. J. Otolaryngol. Soc. Jpn. 4, 2310–2. (1938).

Kimura, R. S. & Schuknecht, H. F. Membranous hydrops in the inner ear of the guinea pig after obliteration of the endolymphatic sac. Pract. Otorhinolaryngol. 27, 343–354 (1965).

Kimura, R. S. Experimental blockage of the endolymphatic duct and sac and its effect on the inner ear of the guinea pig. Ann. Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 76, 664–687 (1967).

Kimura, R. S. Experimental pathogenesis of hydrops. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 212, 263–275 (1976).

Kiang, N. Y. S. An auditory physiologist’s view of Ménière’s syndrome. In Second International Symposium on Ménière’s disease (ed. Nadol, J. B. Jr)13–24. (Kugler & Ghedini, Amsterdam 1989).

Schuknecht, H. F. Pathology of the Ear. 2nd edn. (Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, 1993).

Merchant, S. N., Rauch, S. D. & Nadol, J. B. Meniere’s disease. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 252, 63–75 (1995).

Nadol, J. B. Jr Pathogenesis of Meniere’s syndrome. In Ménière’s Disease, (ed. Harris, J. P.) 73–79 (The Hague, The Netherlands: Kugler, 1999).

Nakashima, T. et al. Grading of endolymphatic hydrops using magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Otolaryngol. 129 (sup560), 5–8 (2009).

Vaidyanathan, A. et al. Deep learning for the fully automated segmentation of the inner ear on MRI. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–14 (2021).

Hussain, R., Lalande, A., Girum, K. B., Guigou, C., Grayeli, B. & A Automatic segmentation of inner ear on CT-scan using auto-context convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–10 (2021).

Zhu, S., Gao, W., Zhang, Y., Zheng, J., Liu, Z. & Yuan, G. 3D automatic MRI level set segmentation of inner ear based on statistical shape models prior. In 2017 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Biomedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI) 1–6 (IEEE, 2017).

Ahmadi, S. A., Raiser, T. M., Rühl, R. M., Flanagin, V. L. & Zu Eulenburg, P. IE-Map: a novel in-vivo atlas and template of the human inner ear. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–16 (2021).

Kirsch, V., Nejatbakhshesfahani, F., Ahmadi, S. A., Dieterich, M. & Ertl-Wagner, B. A probabilistic atlas of the human inner ear’s bony labyrinth enables reliable atlas-based segmentation of the total fluid space. J. Neurol. 266 (1), 52–61 (2019).

Powell, K. A. et al. Atlas-based segmentation of temporal bone anatomy. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 12 (11), 1937–1944 (2017).

Meng, J., Li, S., Zhang, F., Li, Q. & Qin, Z. Cochlear size and shape variability and implications in cochlear implantation surgery. Otol. Neurotol. 37(9), 1307–1313 (2016).

Kendi, T. K., Arikan, O. K. & Koc, C. Volume of components of labyrinth: magnetic resonance imaging study. OtolNeurotol. 26 (4), 778–781 (2005).

Wang, R. et al. Medical image segmentation using deep learning: a survey. IET Image Proc. 16 (5), 1243–1267 (2022).

Niyas, S., Pawan, S. J., Kumar, M. A. & Rajan, J. Medical image segmentation with 3D convolutional neural networks: a survey. Neurocomputing. 493, 397–413 (2022).

Shen, D., Wu, G. & Suk, H. I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 19, 221 (2017).

Liu, X., Song, L., Liu, S. & Zhang, Y. A review of deep-learning-based medical image segmentation methods. Sustainability. 13 (3), 1224 (2021).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image. Anal. 42, 60–88 (2017).

Gürkov, R. et al. MR volumetric assessment of endolymphatic hydrops. Eur. Radiol. 25 (2), 585–595 (2015).

Neves, C. A., Tran, E. D., Kessler, I. M. & Blevins, N. H. Fully automated preoperative segmentation of temporal bone structures from clinical CT scans. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–11 (2021).

Noble, J. H., Labadie, R. F., Majdani, O. & Dawant, B. M. Automatic segmentation of intracochlear anatomy in conventional CT. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 58 (9), 2625–2632 (2011).

Iyaniwura, J. E., Elfarnawany, M., Ladak, H. M. & Agrawal, S. K. An automated A-value measurement tool for accurate cochlear duct length estimation. J. Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surg. 47 (1), 1–8 (2018).

Liu, T., Xu, Y., An, Y. & Ge, H. Intelligent segmentation algorithm for diagnosis of Meniere’s disease in the inner auditory canal using MRI images with three-dimensional level set. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2021 (2021).

Heutink, F., Koch, V., Verbist, B., van der Woude, W. J., Mylanus, E., Huinck, W.,... & Caballo, M. Multi-scale deep learning framework for cochlea localization, segmentation and analysis on clinical ultra-high-resolution CT images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 191, 105387 (2020).

Elfarnawany, M. et al. Micro-CT versus synchrotron radiation phase contrast imaging of human cochlea. J. Microsc. 265 (3), 349–357 (2017).

Franz, D., Hofer, M., Pfeifle, M., Pirlich, M., Stamminger, M. & Wittenberg, T. Wizard-based segmentation for cochlear implant planning. In Bildverarbeitung für die Medizin 2014 258–263 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014).

Naganawa, S. et al. MR imaging of endolymphatic hydrops: utility of iHYDROPS-Mi2 combined with deep learning reconstruction denoising. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 20 (3), 272–279 (2021).

Cho, Y. S., Cho, K., Park, C. J., Chung, M. J., Kim, J. H., Kim, K.,... & Chung, W. H. Automated measurement of hydrops ratio from MRI in patients with Ménière’s disease using CNN-based segmentation. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1–10 (2020)

Park, C. J., Cho, Y. S., Chung, M. J., Kim, Y. K., Kim, H. J., Kim, K.,... & Cho, B. H. A Fully automated analytic system for measuring endolymphatic hydrops ratios in patients With Ménière Disease via Magnetic Resonance Imaging: deep learning model development study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23 (9), e29678 (2021).

Iida, T., Teranishi, M., Yoshida, T., Otake, H., Sone, M., Kato, M.,... & Nakashima, T. Magnetic resonance imaging of the inner ear after both intratympanic and intravenous gadolinium injections. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 133 (5), 434–438 (2013).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 234–241 (Springer, Cham, 2015).

Nogovitsyn, N., Souza, R., Muller, M., Srajer, A., Hassel, S., Arnott, S. R.,... & MacQueen, G. M. Testing a deep convolutional neural network for automated hippocampus segmentation in a longitudinal sample of healthy participants. NeuroImage 197, 589–597 (2019).

Çiçek, Ö., Abdulkadir, A., Lienkamp, S. S., Brox, T. & Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 424–432 (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. ICLR 2019 (2017).

Abraham, N. & Khan, N. M. A novel focal tversky loss function with improved attention u-net for lesion segmentation. In 2019 IEEE 16th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2019) pp. 683–687 (IEEE, 2019).

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 2980–2991 (2018).

Salehi, S. S. M., Erdogmus, D. & Gholipour, A. Tversky loss function for image segmentation using 3D fully convolutional deep networks. In International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging 379–387 (Springer, Cham, 2017).

Naganawa, S., Yamazaki, M., Kawai, H., Bokura, K., Sone, M. & Nakashima, T. Imaging of endolymphatic and perilymphatic fluid after intravenous administration of single-dose gadodiamide. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 11, 145–150 (2012).

Szklo, M. & Nieto, F. J. Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics (Jones & Bartlett, 2014).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 327 (8476), 307–310 (1986).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7132–7141 (2018).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention U-net: learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03999 (2018).

Nodirov, J., Abdusalomov, A. B. & Whangbo, T. K. Attention 3D U-Net with multiple skip connections for segmentation of brain tumor images. Sensors. 22 (17), 6501 (2022).

Futrega, M., Milesi, A., Marcinkiewicz, M. & Ribalta, P.. Optimized U-Net for brain tumor segmentation. In International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop 15–29 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Swin unetr: swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in mri images. In International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop 272–284 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021).

Gao, Y. et al. A data-scalable transformer for medical image segmentation: architecture, model efficiency, and benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.00131. (2022).

Amit, T., Shaharbany, T., Nachmani, E. & Wolf, L. Segdiff: Image segmentation with diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00390. (2021).

Wu, J., Fu, R., Fang, H., Zhang, Y. & Xu, Y. Medsegdiff-v2: Diffusion based medical image segmentation with transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.11798. (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the Biomedical Research Institute at Jeonbuk National University Hospital.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00253003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of study (T-W.Y., C.D.Y., I-S.O., and E.J.L.); Collection of data (T-W.Y., and C.D.Y.); Analysis and interpretation of data (T-W.Y., MW. K. and I-S.O.); Writing the article (T-W.Y., and C.D.Y.); Critical revision and final approval of the article (T-W.Y., C.D.Y., and E.J.L.)

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, TW., Yeo, C.D., Kim, M. et al. Automated volumetric analysis of the inner ear fluid space from hydrops magnetic resonance imaging using 3D neural networks. Sci Rep 14, 24798 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76035-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76035-3