Abstract

Extraction of gas from low-permeability thick coal seams poses challenges globally, attributed to low extraction efficiency, limited enrichment content, and extraction complexities. Investigating static fracturing in low-permeability thick coal seams holds substantial engineering significance and practical utility. This research delves into the current conditions in the Western region, characterized by low gas permeability and challenging extraction in thick coal seams. Through the utilization of FLAC3D and COMSOL, simulation schemes are devised to analyze the influence of borehole parameters on fracture efficacy, elucidating the mechanisms by which external loads and internal gas pressure impact coal seam permeability. Field monitoring tests are employed to evaluate and model gas extraction enhancement via borehole positioning. The results suggest that the application of a static fracturing agent inducing 40 MPa expansion stress, along with a 75 mm borehole diameter and 0.5 m spacing, effectively fractures low-permeability thick coal seams. The spacing between extraction and fracturing holes adversely affects gas extraction efficiency due to the limited range of static fracturing. Field experiments demonstrate that static fracturing significantly improves gas extraction from low-permeability thick coal seams, resulting in a twofold increase in average gas extraction purity post-fracturing. This study establishes a robust theoretical foundation for optimizing gas extraction and mining activities in challenging low-permeability thick coal seam environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

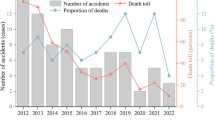

The coal seams in China generally demonstrate low permeability. As mining operations move towards deeper levels, the stress on these seams increases significantly, resulting in reduced permeability and higher gas pressure. This elevated gas pressure increases the risk of potential gas-related disasters1,2,3,4. The research indicates that coal and gas outbursts are primarily attributed to high ground stress and the accumulation of gas in localized areas. Static fracturing is a proven technique for alleviating ground stress in coal deposits, thereby enhancing coal seam permeability and improving gas extraction efficiency. This method offers an innovative approach to mitigating coal seam disturbances. By injecting a static fracturing agent into boreholes and utilizing the resulting expansion stress, this technology fractures rock formations5,6. The efficiency of gas extraction relies on the optimal configuration of fracturing boreholes and their spacing, under a consistent expansion stress from the static fracturing agent. Thus, investigating the impact of static fracturing on coal seams can establish a theoretical foundation for enhancing static fracturing anti-reflection and pumping technologies, as well as refining the static fracturing mechanism. Analyzing the parameters of static fracturing hole layout can offer valuable guidance for preventing mine gas disasters and for the exploration and exploitation of gas resources7,8,9,10.

Extensive research has been conducted by numerous scholars on anti-reflection technology and static fracturing techniques in low-permeability coal seams11,12,13,14,15. Natanzi et al.16 conducted experiments on N-type mortar block specimens and lime mortar specimens to demonstrate the viability of static cracking in building demolition applications. Asadizadeh et al.17 applied radial stress to a Brazilian disc composed of cement mortar to investigate the effects of load direction and intensity on the failure mechanisms of rock masses. The research findings suggest that the tensile strength, stiffness, and failure behavior of the Brazilian disc are significantly affected by the initial crack height within the rock mass. Specifically, when the distance between the two cracks is minimal, the specimen tends to exhibit predominant damage in the form of a step shape. Arshadnejad18 introduced a semi-analytical experimental equation that offers a method for determining the ideal spacing between holes in various types of rocks and concrete. This equation considers the fracturing materials and the diameter of the boreholes. Guo19 and Li et al.20 developed a static model of rock fracture mechanics to simulate the fracturing process. By examining the influence of the water-cement ratio and soaking time on the fracturing agent, they noted that the volumetric expansion rate of the static fracturing agent decreased with increasing water-cement ratio. Moreover, fluidity increased as the water-cement ratio increased, which helped identify an optimal range for the water-cement ratio. Xie et al.21 conducted field experiments to investigate the static cracking expansion stress change and the endoscopic mapping of cracking around pumping holes. Based on their findings, they identified an optimal ratio of borehole spacing to diameter, which was determined to be 14 to 15. Additionally, a consistent parameter was identified to have a direct positive relationship with the fracturing efficiency of the pumping borehole, as influenced by the diameter of the borehole. Wang et al.22,23,24 integrated PFC2D with COMSOL, two numerical simulation software packages, and introduced a method for processing geometric models to facilitate the numerical simulation of gas extraction during hydraulic fracturing. Their study revealed that, in comparison to a water injection pressure of 20 MPa, a pressure of 40 MPa resulted in the generation of a greater number of cracks with a wider extent of propagation. Li et al.25 examined the evolutionary pattern and stress distribution of explosive fractures at the terminations of single and double-blast holes with different distances between them. Their study utilized a combination of experimental methods and numerical simulations. The research revealed that the overlap of explosive stress between double blast holes restricted crack formation on the inner side of the blast holes. Additionally, the distance between the blast holes showed a positive association with both crack arrest time and crack propagation length. Meng et al.26 employed acoustic emission technology to investigate the stress–strain behavior and permeability of coal specimens subjected to varying confining pressures. The coal failure mechanism was categorized into three distinct phases: pore deformation, plastic deformation, and failure instability. The permeability of coal samples was influenced differently by stress-strain at various stages. Currently, static fracturing technology is predominantly employed in engineering blasting, rock cracking, building blasting, and similar applications27,28; however, its application in coal mines is limited. The scholarly research on static fracturing in coal mines primarily focuses on the mechanism of energy release from a fracturing agent, the distribution of fracturing holes, and the evolution of rock fractures during the fracturing process29,30. The research on the deformation and collapse patterns of coal seams, along with the evolution of coalbed methane drainage during static fracturing, is currently inadequate and lacks comprehensive analysis. Therefore, exploring methods to improve permeability and promote drainage in thick, low-permeability coal seams through static fracturing presents a new and promising research direction31,32,33,34.

This study is dedicated to investigating permeability enhancement and gas venting technology for low-porosity, thick coal beds. The research is based on the 12,316 operational sections at Wangjialing Coal Mine, utilizing a comprehensive methodology that integrates theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and field experimentation. The study systematically examines the evolution patterns of coal seam stress, plastic zones, permeability, and coal seam gas pressure during the static fracturing process. The findings shed light on the mechanisms involved in static fracturing in coal seams and the influence of expansion stress on coal seams. Additionally, the study includes the optimization of parameters for static fracturing field trials to determine the optimal spacing between fracturing holes and the ideal distance from the pumping hole to the fracturing aperture.

Methods

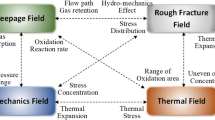

Mathematical model

Coal deformation control equation

In the examination of stress and deformation in gas-bearing coal, it is assumed that the coal exhibits characteristics of a homogeneous, isotropic, linear elastic material, with its deformation following a generalized Hooke’s law. In situations where there is no negative pressure gas extraction, the effects of gas adsorption and desorption on coal are considered minimal, leading to a negligible impact on coal seam deformation. Based on the fundamental principles of elastic mechanics, the effective stress balance equation, constitutive equation, and geometric equation are derived. Subsequently, the deformation control equation for gas-bearing coal seams is obtained35,36.

Where G is the shear modulus of the coal seam, MPa; Fi is the volume force, MPa; v is Poisson’s ratio of coal seam; α is the Biot coefficient; u is displacement, ui, ijuj, ji is tensor form; pi is mechanical tensor form.

Coal seam gas diffusion control equation

In accordance with Fick’s law37, the movement of gas within the pore structure of a coal seam can be characterized by a mass conservation equation. The calculation of gas mass in a specific volume of the coal matrix is accomplished by applying the Langmuir equation and the ideal gas state equation. Gas diffusion proceeds as a result of concentration gradients, leading to the development of the governing equation for gas diffusion within the coal seam38,39,40.

Where φ is the porosity of porous media; r is the pore radius, mm; R is the gas constant, J/(mol·K); T is temperature, K; M is the molar molecular mass, kg/mol; p is the stress within the coal bed, Pa.

Coal seam gas seepage control equation

Gas flow within the fracture system of a coal seam can be considered a seepage phenomenon. By integrating Darcy’s law with the mass conservation equation41, the governing equation for gas seepage in a coal seam is derived as elaborated below42,43:

Where λ is the permeability coefficient tensor of the coal seam, m3/MPa2·d; p is the gas pressure in the coal seam, MPa; R is the gas constant, taking 8.31 J/(mol·K); T is the absolute temperature, K.

Coal seam permeability model

During the extraction of a coal seam, the process of excavating the roadway and extracting the coal seam results in the creation of anticipated fractures in the overlying strata. By integrating the Langmuir equation, it is possible to establish a permeability model that reflects the conditions of damage to the coal seam, as outlined in this context44,45:

Where k0 is the initial permeability of the coal bed, µm2 ; p is the current stress of the coal bed, MPa; p0 is the initial gas pressure of the coal seam, MPa; εL is the Langmuir volumetric strain constant; ϕ0 is the initial porosity of coal seam; K = E/3(1-2v) is the bulk modulus of the coal seam, GPa; pL is Langmuir pressure constant; v is Poisson’s ratio; E is the elastic modulus of coal seam, GPa.

Physical model

Model and boundary conditions

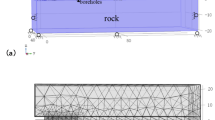

FLAC3D for conducting three-dimensional modeling of the coal bed to assess the impact of the fracturing agent on coal and rock mass under varying borehole apertures and hole spacing. A consistent radial stress of -40 MPa was imposed on the inner wall of the fracturing hole to simulate the expansion stress caused by the fracturing agent. Following the computational analysis, the study examined the progression of stress zones and plastic zones within the coal seam during the fracturing process across different borehole diameters and spacing. Figure 1 depicts the initial model, with the X-axis measuring 8 m, the Y-axis measuring 40 m, and the Z-axis measuring 7.9 m. In accordance with the current conditions of the 12,316 site at Wangjialing Coal Mine, the burial depth of the model has been established at 400 m, with a vertical downward stress of 10 MPa applied.

To comprehensively and objectively evaluate the influence of different extraction hole spacing on gas extraction subsequent to coal seam fracturing, a two-dimensional plane model of the coal seam was developed utilizing COMSOL Multiphysics. This model facilitated the simulation of gas extraction results across various spacing arrangements. Figure 2 is the initial model of COMSOL numerical simulation. Among them, the spacing of fracturing holes is 0.5 m, the diameter of fracturing holes and extraction holes is 75 mm, and the spacing of extraction holes is 0.6 m, 1.0 m, 1.4 m, and 1.8 m respectively. The model has an overall length of 6 m and a height of 3 m. In the established model, the boreholes are positioned based on the experimental layout, applying a radial expansion stress of 40 MPa in the fracture hole and a negative pressure of 20 kPa in the extraction hole. During the gas pressure calculations, all boundaries of the coal seam were identified as non-flow boundaries. The extraction hole wall was characterized as a Dirichlet boundary. Using gas pressure and permeability of the model as metrics, the model’s fracturing impact is assessed efficiently, leading to the determination of the optimal spacing separating the extraction borehole and fracturing borehole.

Parameter setting

Wangjialing Coal Mine is a large modernized mining operation with an annual production capacity of 6.0 million tons. It utilizes fully mechanized top coal caving technology to extract the No.2 coal seam, which contains 4 to 6 cubic meters of gas per ton. The mine releases gas at a rate of 12 to 15 cubic meters per minute, making it a typical high gas mine with efficient operations on low gas coal seams. This research specifically examines a 900-meter segment of the return airway in the 12,316 extraction area of the No.2 coal seam at Wangjialing Coal Mine. The study involves assessing the conditions of the belt roadway at the fully mechanized 12,316 extraction site, measuring rock mechanics parameters outlined in Table 1, obtaining the rock strata properties illustrated in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

The simulation results under various borehole diameters and spacing

To establish an appropriate drilling spacing for static fracturing in practical engineering applications and to enhance the understanding of the fracturing effects of fracturing agents on low-permeability thick coal seams, this simulation primarily focused on the stress distribution characteristics surrounding the drilling holes and the dimensions of the plastic zone within the numerical simulation model. The research includes four groups of numerical simulation schemes labeled as A, each with different fracture hole diameters (fracture hole spacing of 1.0 m and hole diameters of 45 mm, 55 mm, 65 mm, and 75 mm respectively). Furthermore, four groups of numerical simulation schemes labeled as B are established with varying fracture hole spacing (fracture hole diameter of 75 mm and hole spacing incrementing by 0.5 m between holes).

Analysis of stress distribution characteristics

Figure 4 illustrates the stress distribution cloud diagram of the model under different hole apertures. As the fracture hole diameter increases, the area of the model’s stress change gradually increases. The shape of the innermost stress circular area of the fracture hole begins to be irregular, which indicates that the interaction between the expansion stresses in the two fracture holes separated by 1 m is enhanced. When the aperture increases to 75 mm, the horizontal effect of stress is basically the same as the vertical effect. Figure 5 illustrates the stress distribution cloud diagram of the model under different hole spacing. With an increase in hole spacing, at 1.0 m spacing, the core area S undergoes horizontal contraction and vertical elongation. Further spacing increments to 2.0 m result in the expansion of regions S1 and S2 compared to a 1.5 m spacing. This observation indicates that the expansion stress induced by two fracture holes is nearly equal to the stress generated by a single hole.

The center of the fracture hole axis is chosen as the monitoring position to derive stress value changes, and the resulting curve is depicted in Fig. 6. In the operation process of 0–4000 steps, the larger the aperture is, the greater the fluctuation degree of the stress change is, and the more obvious the fluctuation of the stress curve is. Figure 6b shows that the peak stress at this point is highest when the hole spacing is 0.5 m. The variation in stress is moderate when the hole spacing ranges from 1.0 m to 1.5 m, the peak stress is at its minimum when the interval is 2.0 m. As the hole spacing increases by the same increment, the stress decreases progressively, indicating a more pronounced effect of the fracture hole stress on the coal body near the hole. Therefore, in practical static fracturing applications, to achieve optimal fracturing results, the spacing of the fracturing holes should be under 1.0 m and should not exceed 1.5 m to ensure optimal results.

Evolution analysis of plastic zone

Figure 7 illustrates the evolution cloud diagram depicting the plastic zone of the model under different hole apertures. For a fracture hole diameter size of 45 mm, the plastic zone in the model induced by expansion stress primarily consists of a shear plastic failure zone. With an increase in the fracture hole aperture to 55 mm, a shear plastic failure zone emerges within the plastic region affected by expansion stress, persisting until the aperture reaches 65 mm. Upon further expansion to 75 mm, the entire plastic zone resulting from expansion stress transitions into a shear failure zone. At this stage, the model demonstrates significant and stable damage, with no additional shear or tensile failures observed. Figure 8 reveals that with a hole spacing of 0.5 m, the plastic zone resulting from stress from both holes exhibits a vertically oval shape. Horizontal plastic deformation occurs at the midpoint of the axes of the two holes, with significant plastic deformation in the roof section. As the hole spacing increases, the plastic zone formed by the hole transitions from an ellipse to a figure resembling the number ‘8’. Subsequently, the plastic region of the model primarily surrounds the hole, forming two elliptical regions centered on it, while the horizontal plastic deformation area at the midpoint of the two hole axes decrease.

Based on the aforementioned findings, a gradual enlargement of the diameter of the fracturing hole beyond 75 mm has a minimal impact on improving the fracturing effect of the coal seam. However, the increase of the fracture hole leads to higher drilling costs, thereby reducing the efficiency of the fracturing equipment. Moreover, as the distance between the holes increases, the interaction between two adjacent cracking holes decreases significantly. Consequently, the effectiveness of double-hole cracking diminishes and becomes similar to single-hole cracking under combined stress conditions. Therefore, in the field of static fracturing engineering, establishing drilling parameters such as a vertical hole arrangement with a diameter of 75 mm and a spacing of 0.5 m can enhance engineering efficiency while fulfilling the necessary fracturing criteria.

Simulation analysis of seam gas drainage hole layout parameters

Static fracturing disrupts the coal body and influences the coal bed’s permeability. The gas flow is treated as transmission through a porous medium. Darcy’s law is employed to describe the gas permeability effect, while Fick’s law is used to represent the gas diffusion effect. The changes in gas pressure within the extraction hole during the fracturing process are simulated using COMSOL. Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of gas pressure within the coal seam. The diagram illustrates that as borehole spacing increases, the impact of gas pressure reduction within the coal seam diminishes progressively. This phenomenon can be attributed to the synergistic effects of coal failure and the redistribution of stress surrounding the fractured boreholes, both of which collectively influence the permeability of the coal seams. When the distance from the fracturing hole is excessive, the fracturing effect on the coal seam becomes less pronounced, resulting in minimal changes in permeability and a less effective extraction outcome. Conversely, a closer spacing yields improved extraction results.

When the spacing reaches 1.8 m, the effect of gas reduction within the coal seam becomes negligible after one day of extraction. In contrast, at a hole spacing of 0.6 m, after one day of extraction. This observation indicates the development of a fracture network within the coal seam surrounding the crack hole at a spacing of 0.6 m, resulting in a uniform reduction in gas pressure across the area. At this spacing, observations reveal that after 16 days of extraction, the internal yellow region on the gas pressure cloud map begins to transition from a circular shape to one resembling lateral water droplets. By the 24-day mark, the yellow regions associated with the two extraction holes have merged in the direction of the fracture hole. This phenomenon can be attributed to the proximity of the extraction hole to the fracture hole. During the static fracturing process, the extraction hole exerts a guiding influence on the fracture, causing the fracture that develops to extend toward the extraction hole. In the subsequent phase of negative pressure extraction following fracturing, a more pronounced decrease in gas pressure is observed in the direction of the fracture hole, with a larger area experiencing this decline. Furthermore, the relatively small diameter of the extraction hole (0.075 m) results in a high permeability zone that is confined to a limited area surrounding the extraction hole due to coal seam failure. Within this region, the gas pressure drop can reach 0.12 MPa. Conversely, in the vicinity of the high permeability zone, the stress concentration effect leads to the formation of a low permeability zone within the coal seam, where the gas pressure drop is comparatively minimal. To ensure effective extraction under practical mine conditions, it is recommended that the spacing (l) between the extraction borehole and fracturing borehole be less than 1.4 m when employing static fracturing.

Using COMSOL Multiphysics numerical simulation software, coal seam gas pressure data were obtained at various times and different hole distances. These results were then plotted as a two-dimensional curve, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10 reveals that along with the spacing between extraction holes augments, the stress within the coal bed in the central area between the two holes gradually rises. Specifically, for hole spacing of 0.6 m and 1 m, Fig. 10a and b show that the midpoint gas pressure coal bed area between the two extraction holes is significantly lower than on either side, an effect not as evident in the other Figures. Additionally, Fig. 10a and b display different rates of gas pressure reduction during the same negative pressure extraction period, which is related to the initially high gas content and stress within the coal bed at the onset of static fracturing. The transmission capacity of coal bed methane increases from high to low concentration areas, and it is released along the extraction hole due to the combined effects of self-diffusion and negative pressure extraction. Consequently, the gas extraction effect during this process is noticeable. As the gas content in coal seams diminishes, the efficacy of gas diffusion correspondingly declines. The primary driving force behind gas migration is the negative pressure created during extraction; thus, a reduction in gas pressure leads to a decrease in gas migration.

Coal permeability is one of the evaluation indexes of the static fracturing effect. Taking the horizontal line at the midpoint of the fracture hole axis as the monitoring object, the evolution law of coal permeability with time in this area is measured, as shown in Fig. 11.

Upon the complete reaction of the static fracturing agent, the internal structure of the coal body is predominantly influenced by geostress and gas pressure, both of which significantly impact variations in coal permeability. As the process of negative pressure extraction advances, the gas pressure within the coal seam progressively decreases, resulting in geostress becoming the primary force acting on the coal seam. As a consequence, the fractures within the coal seam begin to close, which leads to a gradual reduction in permeability. Figure 11 shows that immediately after static fracturing, at 0 days, gas extraction has not yet begun. At this point, the coal seam’s maximum permeability is observed at the midpoint between the two fracturing holes, reaching approximately 10.15 × 10− 14 m2. This represents a roughly 50-fold increase compared to the initial permeability of 0.2 × 10− 14 m2. Additionally, Fig. 11 illustrates that as one moves closer to the fracturing hole area, the flow capacity curve of the coal seam becomes steeper, indicating a more significant alteration. Conversely, further away from the fracturing hole area, the permeability curve levels out, showing smaller changes. This phenomenon shows that the degree of deformation and failure of the coal seam is inversely proportional to the hole spacing, which is consistent with the FLAC3D simulation results. Hence, a shorter spacing l separating the extraction borehole and fracturing borehole results in a more effective extraction.

Static cracking field test

Experimental scheme arrangement

Based on the simulation results and the actual layout of gas extraction boreholes in Wangjialing Coal Mine, a double-hole static fracturing scheme was implemented. The static cracking test site was selected alongside the roadway, 900 m away from the return airway of the 12,316 working face. A total of 12 boreholes were drilled, each with a diameter of 75 mm. Among these, boreholes No.2, 3, 6, 7, 10, and 11 were designated as fracturing boreholes, while No.1, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 12 served as drainage boreholes, all inclined upwards at 5°. The spacing between fracturing holes was set at 0.5 m, while the extraction holes were uniformly spaced at 2.2 m. For comparative testing purposes, the six extraction holes were categorized into six groups based on their distances from the midpoint along the axis of the fracturing holes. The specific arrangement of the boreholes is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Experimental process

During the planning of the construction scheme for the 12,316 working face, predrilling of fracturing and extraction holes was conducted in the fractured coal seam. This design was formulated considering the site conditions and drilling parameters derived from simulation analysis. The specific process flow is depicted in Fig. 13.

Measured data and analysis

Upon the completion of the construction of boreholes No.1 to No.12, boreholes No.1, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 12 designated for investigation and extraction are sealed. Subsequently, within 8 h of sealing the extraction borehole, the extraction pipe valve is opened to commence negative pressure extraction, with the negative pressure level maintained at 20KPa. Simultaneously, the mixed flow and gas concentration prior to static fracturing are monitored, and the daily flow variations of the borehole are documented. Boreholes No.2, 3, 6, 7, 10, and 11 designated for fracturing are also sealed. Additionally, a grouting pipe and an exhaust pipe are installed at the orifice and the base of the hole for the injection of the expansion fracturing agent. Following a continuous monitoring period of 7 days for flow and gas concentration data in the drainage borehole, the static fracturing treatment of the fracturing borehole is executed on the 8th day. The negative pressure of the drainage system is observed to remain stable within 24 h post-grouting. Daily employment of a wet flow meter and an optical gas detector is conducted to monitor changes in flow and gas concentration in the drainage borehole, evaluating the effectiveness of static fracturing in enhancing drainage. The gas purity data from each monitored borehole over a 30-day period is illustrated in Fig. 14.

The analysis of Fig. 14 reveals that the volume of pure gas extracted from individual boreholes remains consistently low in the 7 days leading up to the static fracturing process. Following the application of double-hole static fracturing treatment, there is a notable increase in gas extraction from each monitoring borehole, with an average enhancement of 2.1–2.5 times compared to pre-fracturing levels. Particularly, the No.12 borehole, characterized by the smallest hole spacing, exhibits the most significant increase in gas extraction, reaching 0.012 m3/min after the initial day of fracturing and subsequently stabilizing at 0.0075 m3/min. In contrast, the No.9 borehole, situated at the farthest distance of 1.6 m, maintains a gas extraction rate of 0.012 m3/min. Over time, the volume of pure gas extracted from each monitoring borehole generally shows a gradual decrease.

Based on the analysis provided above, subsequent to the implementation of the static fracturing treatment on the No.2 coal seam at the 12,316 extraction location within the Wangjialing Coal Mine, a notable enhancement in gas drainage efficiency has been observed. This enhancement holds the promise of potentially doubling the volume of gas extraction. Additionally, the inspection of extraction orifices at varying distances indicates that upholding a horizontal separation distance of less than 1.6 m between the extraction well and the fracturing well can significantly enhance pressure alleviation, permeability, and gas extraction efficacy.

Conclusions

This study has chosen Wangjialing Coal Mine as the site for conducting field test research. By utilizing a comprehensive research methodology that encompasses theoretical analysis, numerical simulations, and field tests, the investigation explores the variations in coal seam stress, plastic zone, permeability, and gas pressure throughout the static cracking process. The key findings of the study are outlined below:

-

(a)

The research indicates that, with a static fracturing agent generating 40 MPa expansion stress, employing a 75 mm hole diameter and 0.5 m hole spacing notably enhances the permeability of the coal seam. Specifically, in the central area between the two fracturing holes, the permeability of the coal seam increases by approximately 50 times.

-

(b)

The stress within the coal bed decreases gradually as the duration of negative pressure extraction increases, leading to an expansion of the area of pressure reduction over time. The effectiveness of gas removal is inversely proportional to the distance between fracture holes. A shorter distance between fracture holes leads to improved gas extraction and reduced stress within the coal bed. Setting the hole spacing at 0.6 m maintains the overall gas pressure in the model at around 1.4 × 105Pa after 30 days of negative pressure extraction.

-

(c)

Field test results suggest that employing static fracturing with a hole spacing of 1.6 m and a negative pressure of 20 kPa leads to a notable improvement in gas extraction from low permeability thick coal beds. Following the fracturing process, there is a twofold increase in the average gas extraction purity, and the stress levels within the coal bed decrease to a point that guarantees safe mining operations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reason able request.

References

Wang, K. & Du, F. Coal-gas compound dynamic disasters in China: a review. Process. Saf. Environ. Protect.133, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.10.006 (2020).

Yuan, L. Theory and technology considerations on high-quality development of coal main energy security in China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci.38, 11–22. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20220819002 (2023).

Fu, E., Bai, R., Liu, G., Zhao, H. & Yang, C. Analysis on characteristics and evolution trend of coal mine accidents in our country during the 13th five-year plan period. China Saf. Sci. J.32, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2022.12.0076 (2022).

Zhang, L., Zhang, H. & Guo, H. A case study of gas drainage to low permeability coal seam. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol.27, 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.05.014 (2017).

Luo, M., Li, S., Li, Z. & Fan, C. Composition and performance of static cracking agent in coal and rock fracturing. Eng. Blast.23, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-7051.2017.03.002 (2017).

Fu, S., Wei, S., He, N. & Li, H. Research status and development trend of lime base static crushing technology. China Energy Environ. Prot.42, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.19389/j.cnki.1003-0506.2020.02.032 (2020).

Marsden, H., Basu, S., Striolo, A. & MacGregor, M. Advances of nanotechnologies for hydraulic fracturing of coal seam gas reservoirs: potential applications and some limitations in Australia. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol.9, 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00497-x (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Safe strategy for coal and gas outburst prevention in deep-and-thick coal seams using a soft rock protective layer mining. Saf. Sci.129, 104800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104800 (2020).

Jin, K. et al. Evaluation of the remote lower protective seam mining for coal mine gas control: a typical case study from the Zhuxianzhuang Coal Mine, Huaibei Coalfield, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng.33, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.05.004 (2016).

Guo, B., Zhong, P., Zhang, Z., Cheng, S. & Wang, C. Improvement of thick coal seam gas drainage efficiency using highly pressurized multidischarge CO2 gas fracturing technique. ACS Omega 08651. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c08651 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Research method of pressure relief and permeability enhancement in low permeability coal seam: a review. AIP Adv.12, 010702. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0078373 (2022).

Ma, G. et al. Theory and technique of permeability enhancement and coal mine gas extraction by fracture network stimulation of surrounding beds and coal beds. Nat. Gas Ind. B1, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ngib.2014.11.012 (2014).

Xu, S., Hou, P., Li, R. & Suorineni, F. T. An improved outer pipe method for expansive pressure measurement of static cracking agents. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol.32, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.11.011 (2022).

Liu, X., Liu, J., Li, S., Du, J. & Yang, W. Research progress and comments on cracking agent. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng.392, 032044. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/392/3/032044 (2018).

Liu, J., Zhang, L., Wei, Y. & Wu, Z. Coupling model of stress–damage–seepage and its application to static blasting technology in coal mine. ACS Omega6, 34920–34930. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c05574 (2021).

Natanzi, A. S., Laefer, D. F. & Zolanvari, S. M. I. Selective demolition of masonry unit walls with a soundless chemical demolition agent. Constr. Build. Mater.248, 118635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118635 (2020).

Asadizadeh, M., Shakeri, J. & Nima Babanouri, R. M. Tensile behavior of Brazilian disks containing non-persistent joint sets subjected to diametral loading: experimental and numerical investigations. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech.125, 103829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103829 (2023).

Arshadnejad, S. Design of hole pattern in static rock fracture process due to expansion pressure. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci.123, 104100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104100 (2019).

Guo, H. & Zhu, L. Research on mechanism of energy release and permeability improvement in coal strata by static blasting. China Saf. Sci. J.30, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2020.05.010 (2020).

Li, C., He, S., Hou, W. & Ma, D. Experimental study on expansion and cracking properties of static cracking agents in different assembly states. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol.32, 1259–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2022.09.001 (2022).

Xie, X., Liu, J., Wang, L. & Fang, J. Testing study of expanding and cracking outburst coal seam by the static expansion agent. J. China Coal Soc.41, 2620–2625. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2016.0256 (2016).

Wang, S., Wang, G., Chen, X., Fan, J. & Chi, L. Study on permeability improvement and gas extraction by coal seam hydraulic fracturing based on PFC2D-COMSOL numerical simulation. Saf. Coal Mines53, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.13347/j.cnki.mkaq.2022.10.018 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. N2 injection to enhance gas drainage in low-permeability coal seam: a field test and the application of deep learning algorithms. Energy290, 130010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.130010 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. A numerical investigation of hydraulic fracturing on coal seam permeability based on PFC-COMSOL coupling method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol.9, 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00484-2 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Study on mechanical behaviors of crack dynamic propagation at the end of cylinder blastholes. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng.38, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2018.1096 (2019).

Meng, Z. et al. Experimental analysis of stress-strain, permeability and acoustic emission of coal reservoir under different confining pressures. J. China Coal Soc.45, 2544–2551. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.DZ20.0479 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Zou, J. Research on collaborative control technology of coal spontaneous combustion and gas coupling disaster in goaf based on dynamic isolation. Fuel321, 124123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124123 (2022).

Qin, Y., Xu, H., Liu, W., Liu, J. & Duan, W. Time- and pressure-independent gas transport behavior in a coal matrix: model development and improvement. Energy Fuels34, 9355–9370. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c01182 (2020).

Zhang, M. & Jiang, F. Rock burst criteria and control based on an abutment-stress‐transfer model in deep coal roadways. Energy Sci. Eng.8, 2966–2975. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.715 (2020).

Guo, S. et al. Numerical investigation on rock fracture induced by a new directional rock-breaking technology. Eng. Fract. Mech.268, 108473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108473 (2022).

Cui, F. et al. Mechanism and application of static fracturing technology on deep working face. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng.2021, e5516326. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5516326 (2021).

Liu, C., Yang, J. & Yu, B. Rock-breaking mechanism and experimental analysis of confined blasting of borehole surrounding rock. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol.27, 795–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.07.016 (2017).

Wang, M., Chen, L., Zhou, Y. & Tao, W-Q. Numerical simulation of the physical–chemical–thermal processes during hydration reaction of the calcium oxide/calcium hydroxide system in an indirect reactor. Transp. Porous Media140, 667–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-020-01514-w (2021).

Fan, C. et al. Research advances in enhanced coal seam gas extraction by controllable shock wave fracturing. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol.11, 39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-024-00680-2 (2024).

Hu, S., Wang, E. & Kong, X. Damage and deformation control equation for gas-bearing coal and its numerical calculation method. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng.25, 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.04.039 (2015).

Wu, X. et al. Plastic deformation-based constitutive relation of coal damage and permeability model. Coal Geol. Explor.49, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2021.06.016 (2021).

Huo, B., Jing, X., Fan, C. & Han, Y. Numerical investigation of flue gas injection enhanced underground coal seam gas drainage. Energy Sci. Eng.7, 3204–3219. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.491 (2019).

Xu, H. et al. Modeling of diffusion kinetics during gas adsorption in a coal seam with a dimensionless inversion method. Fuel326, 125068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125068 (2022).

Zhou, X., Han, M., Bai, G., Lan, A. & Fu, Z. Experimental study on the influence of CO2 injection pressure on gas diffusion coefficient. Coal Geol. Explor.49, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2021.01.008 (2021).

Qin, Y., An, F., Su, W., Jia, H. & Chen, X. Direct determination of the diffusion coefficient variation of coal based on Fick’s law and model establishment. Coal Sci. Technol.51, 140–149. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2022-0966 (2023).

Ahamed, M. A. A. et al. Effective application of proppants during the hydraulic fracturing of coal seam gas reservoirs: implications from laboratory testings of propped and unpropped coal fractures. Fuel304, 121394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121394 (2021).

Su, Z. & Wei, S. X-shaped real fracture channels-based simulation of coal seam gas seepage. Coal Geol. Explor.48, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2020.06.015 (2020).

Guo, H., Tang, H., Wu, Y., Wang, K. & Xu, C. Gas seepage in underground coal seams: application of the equivalent scale of coal matrix-fracture structures in coal permeability measurements. Fuel288, 119641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119641 (2021).

Rong, T., Zhou, H., Wang, L., Ren, W. & Guo, Y. A damage-based permeability models of deep coal under mining disturbance. Rock. Soil. Mech.39, 3983–3992. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2018.0787 (2018).

Rong, T. et al. Permeability evolution of deep coal under mining stress. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng.44, 1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE202206015 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 51904266], Excellent youth project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education [grant numbers 21B0144], Hunan Natural Science Foundation Youth Program [grant numbers 2023JJ40634] and the Open Fund Project of State Key Laboratory of Mining Response and Disaster Prevention and Control in Deep Coal Mines[grant numbers SKLMRDPC23KF04].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. X. W. plays a guiding role in conceptualization, method and resources; F. H. mainly takes charge of paper writing, and he made a great contribution to the revision; H. X. and C. Z. main contributions are in data management, resources, writing review and editing; T. J. and Y. J. provided guidance on essay writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Hao, F., Xu, H. et al. Static expansion fracturing mechanism for enhancing gas permeability in low permeability coal seams. Sci Rep 14, 25046 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76071-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76071-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on static expansive fracturing for pressure relief and rockburst prevention in coal seam boreholes

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Development and application of an improved constitutive model for acidizing coal around fractured boreholes

Scientific Reports (2025)