Abstract

Climate change and its negative effects are driving the global shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. To tackle the dependency on traditional energy sources in harsh winter regions and improve heating quality during periods of thermal demand fluctuations, this paper proposes a new distributed heating peak shaving system (DHPS). The system combines municipal heat and clean energy within the secondary network while reducing the return water temperature in the primary network. It comprises solar collectors, electric thermal storage tanks (ETST), and absorption heat pump (AHP) units, integrated into conventional heat exchange stations. The system operates in two modes to manage peak and off-peak loads respectively, with TRNSYS simulation used to evaluate performance across a range of peak-shaving gradients. A multidimensional comprehensive assessment is conducted between the DHPS under optimal peak shaving coefficient (θ) conditions and conventional peak clipping boiler (PCB). Results indicate that DHPS achieves a high primary energy ratio (PER) of 1.251 at θ = 0.5, reducing combustion emissions by nearly 40%. The static payback period (PBP) of the system is 3.5 years. When the electricity price drops to 0.275 CNY, its operational costs are comparable to PCB. DHPS caters to the energy characteristics of cold regions where electricity supply exceeds demand. It enables flexible peak shaving while ensuring the complete utilization of clean energy and effectively utilizing waste heat from power plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of economy and technology, energy consumption has significantly increased, resulting in ecological deficits such as the depletion of non-renewable energy sources1. More than 50% of global energy consumption is attributed to heat generation, with the majority of this energy derived from non-renewable sources2. Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems are widely used to supply heat to buildings in regions with high heat demand density. These systems optimize overall energy utilization by generating electricity and heat from a single fossil fuel source while recovering heat that would otherwise be wasted. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that the demand for energy to provide heating comfort in buildings will double by 2050, posing a significant decarbonization challenge in cold regions where CHP systems are vital during winter3,4. Increasing the share of renewable energy applications in heating systems, adjusting the energy mix of heat sources, and creating space for residual energy are the primary strategies for reducing and neutralizing carbon emissions5.

As urban expansion continuously increases the demand for heat, the basic heat source of CHP systems frequently proves inadequate to meet peak load demands. In order to resolve this issue, adjustments need to be made either at the heat source end or the heat user end under suitable peak shaving coefficients (\(\:\theta\:\)) 6,7, which indicate the energy system’s ability to reduce peak period energy demand through adjustments in heat source output. Adjustments to the heat source unit capacity involve significant engineering efforts. They can lead to excessive time and technical costs, along with economic and social sustainability limitations due to primary energy consumption8. Consequently, current research on heat source adjustments primarily explores the addition of recoverable waste heat-based heat pumps and thermal storage auxiliary equipment in power plants9,10,11. Although this approach somewhat reduces coal consumption while compensating for peak loads, it presents negative impacts on heat loss along the distribution network and peak shaving response12.

Therefore, among various techniques to accommodate different load curves, implementing Demand side management (DSM) and integrating fossil and renewable energy sources offer advantages in improving comprehensive peak-shaving thermal efficiency and conserving heat flow13,14. Typically, these strategies are implemented through peak-shaving modifications in secondary network systems. The secondary network acts as a heat exchange hub, distributing low-temperature, low-pressure hot water to end users after exchanging heat from the primary network. It ensures efficient thermal transfer over short distances to meet heating demands. Ju15 demonstrated the effectiveness of end-user buffering thermal storage tanks in reducing peak power and satisfying building heat demands. Zhang9 proposed an efficient heating technology integrating geothermal water into the secondary network through absorption heat pumps (AHP) and simulated it using MATLAB, showing a 25.6% reduction in heating season pollutant emissions compared to traditional systems. Similarly, Li16 introduced two driving modes of AHP integrated into heat exchange stations for peak load heating, finding a decrease in heating cost per unit distance of the heat network to 27.36 CNY/GJ when θ = 0.3. In many industrial processes, cooling systems result in heat being discharged into the environment through cooling media, leading to significant resource waste. Song17 predicted that waste heat has the potential for large-scale utilization in China by 2025 and proposed the construction of distributed systems at the end of the heat network to balance regional heating fluctuations. Meanwhile, the Central People’s Government is promoting the development of new energy types and energy storage technologies in communities with high-density heat demand to ensure thermal efficiency in the heating system reform18. In summary, adopting a distributed innovative heating model based on clean energy coupling can facilitate the achievement of low-carbon economies of scale in obtaining heat.

The aforementioned research found that AHP can be effectively applied on the heating demand side due to its ability to recover waste heat by increasing the temperature difference between supply and return water. It requires a stable and continuous heat source to drive its operation. Direct utilization of district heating network water involves complex operation and maintenance, and significant heat energy consumption from CHP. Coupling AHPs with clean energy has gained widespread favor for constructing distributed systems. Solar energy stands out in terms of the application of clean energy due to its wide distribution and ease of collection. In order to address the variability and enhance the energy contribution, coupling systems are considered the optimal choice19. Su and Yang20 developed a renewable hybrid power system driven by solar energy and sky radiation cooling, applying peak shaving strategies. They found that the system efficiently meets carbon capture and wastewater treatment requirements. Li21 established a novel solar thermal combined heat and power system coupled with AHPs distributed systems, recovering all condensate waste heat and achieving energy efficiency of 80.5%. Dai22 proposed a hybrid liquefied petroleum gas and solar-driven AHP heating system. Experimental data indicates that under typical climate conditions, the heating coefficient of performance (COP) of the AHP reached 1.82, with a solar thermal efficiency of 40%. Ramzan1 summarized the current coupling technologies of solar energy with various AHP configurations and proposed that incorporating thermal storage materials could synergistically enhance efficiency. Chen23 conducted an economic evaluation of solar-driven AHP in Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power (CCHP) systems, revealing a payback period of 3.5 years for investment, with component unit costs decreasing as annual operation time increased. These studies demonstrate that combining solar energy with energy storage devices and AHP can increase their respective energy contribution, and the overall system can achieve a high-quality heating supply. However, the feasibility of these systems in cold regions, which consume the most energy for heating, still needs to be discovered. Its potential for applying heat peaking is currently of urgent research value.

To mitigate the severe energy consumption conflict of “surplus electricity with concurrent heat energy deficit” in CHP for cold regions, it is possible to apply a solar-driven AHP system for heating peak shaving. This approach flexibly meets building heat demands while utilizing waste heat from power plants. Based on the current research gap and crucial directions in this field, this paper proposes a novel distributed heating peak shaving system (DHPS) that coupling solar collectors with AHP and is retrofitted within secondary network heat exchange stations. The system conducts operating condition simulations using TRNSYS under various θ and verifies the reliability of the system model by comparing it with collected municipal network data. The research proposes two operating modes for peak and off-peak thermal load periods: municipal coupling and direct supply using solar energy and electric heating. Then, the optimal θ is determined through calculations and compared with traditional peak shaving heat sources using multi-objective comprehensive sustainability assessments. DHPS effectively achieves the cascade utilization of energy, providing a diverse selection for the coupled heating application of renewable energy in cold regions.

Materials and methods

Study case

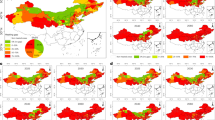

This study focuses on a heating area in Changchun, Jilin Province, China, as shown in Fig. 1, where the red pipelines delineate the current peak-shaving operational scope of the district’s peak clipping boiler (PCB). The focal point of investigation is a heat exchange station within a moderately sized heating radius. Its total rated heating capacity is 6.95 MW, covering an area of approximately 126,500 m2. Changchun is classified as a severely cold climate region. In winter 2021, the average outdoor temperature dropped to − 10.8 °C, while indoor temperatures were maintained at 18 °C. The heating period lasts for 169 days. A thermal power plant primarily heats the municipal pipeline network. Low-capacity thermal peak-shaving boilers have gradually replaced their predecessors in compliance with relevant environmental regulations. As a result, a single circulating fluidized bed hot water boiler with a total capacity of 91 MW now manages the peak heating load in this area. The research area covers 20% of the heating radius serviced by this peak-shaving coal-fired boiler. Table 1 shows the rated operational parameters of the heating units.

(Generated by ArcGIS10.5.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index;

AutoCAD2025, https://www.autodesk.com/jp/products/autocad/overview?%20term=1-YEAR)

The data pertaining to heat load was obtained from the designated heat exchange station. Outdoor temperature and solar radiation intensity were measured using a meteorological instrument manufactured by Rainwise Inc., as shown in Fig. 2, with an accuracy of ± 3%. Measurements were taken in unobstructed areas, facing south, at 15-minute intervals. The study collected data from January to the end of March 2021, encompassing a 90-day operational span of the peak-shaving system for heating supply. Calculated based on continuous operation throughout the day, this equates to 2160 h of peak-shaving operation. The initial two-month (60-day) period represents the peak heating period, with a total duration of 1,440 h. Solar radiation intensity for each month is illustrated in Fig. 3a, 3b, and 3c. The analysis demonstrates an inverse correlation between the average outdoor temperature during winter and the daily load demand within the region as shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the variation in the daily total load values indicates that the selected time interval appropriately captures the variability in heat load peaks and valleys, facilitating a comprehensive study of heat load dynamics.

System description

This paper proposes a distributed heating peak shaving system (DHPS), which integrates indirect solar flat plate collectors, electric thermal storage tank (ETST) and AHP, is retrofitted in parallel with a traditional heat exchange station to enable peak-shaving for heating, as shown in Fig. 5. The DHPS combines centralized conventional heat sources with distributed clean energy, enabling coordinated operation. The operational process of the system is as follows:

During periods of high load demand, the solar collectors absorb solar radiation to heat the working medium. The heated medium exchanges heat with the water in the ETST through a small heat exchanger configured in the collector (flow①). After the heat exchange process, the water is either insulated or electrically heated to the specified outlet temperature, then flows towards the generator of the AHP as the driving heat source (flow②).

AHP operates under a defined low-pressure environment utilizing lithium bromide (LiBr) and water as a working pair, with LiBr’s notable absorptive properties24. The application of heat facilitates the phase change of the dilute LiBr solution within the generator, resulting in its boiling and transformation into high-temperature steam, which flows to the condenser. At this juncture, a portion of the water from the secondary network enters the condenser as cooling water, absorbing the steam’s heat (flow③). Following the heating of the water, it is mixed with another stream that has undergone a heat exchange at the heat exchange station. This allows the temperature of the mixed water to meet the peak-shaving heating demand. The condensed saturated water undergoes isenthalpic pressure reduction before entering the evaporator, where it absorbs heat from the return water of the primary pipe network and evaporates back into steam (flow④). Finally, the steam enters the absorber, where it is absorbed by the concentrated LiBr solution. This cyclical process guarantees the quality of the peak-shaving heat supply while simultaneously increasing the temperature differential between the supply and return water, thereby enhancing the efficiency of waste heat recovery within the heating system.

During the period of heat load valley, when the heat load demand decreases and solar radiation increases, the primary network ceases operation. The solar collectors and ETST are the only active components providing hot water to the secondary network, meeting the entire user’s heat load requirements through heat exchange station (flow⑤).

Based on the collected trends in heat demand and the corresponding heat source management distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 6, the shaded area represents the heat load managed by the power plant. Within this range, the CHP units operate close to their rated capacity. The remaining heat load is handled by peak-shaving equipment. Heat load demand exhibits significant fluctuations within 24 h due to the influence of outdoor temperature, which can often oppose the trend of solar radiation intensity. In other words, when the rate of energy capture is high, the level of heat demand is correspondingly low. Therefore, substantial scheduling space maneuverability is required to facilitate energy transfer. The operational control strategy devised in this study is as follows: The solar collector operates when the temperature difference (Δt) between the outlet temperature of the solar collector (\(\:{t}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{n},\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\)) and the average temperature of the first layer of the ETST (\(\:{t}_{1}\)) exceeds 8 °C.Δt = 8 °C is an optimized value for heat transfer efficiency and operational stability, determined after experiments and analysis of long-term operational data25. Based on the load provided by the AHP in this case, the driving water temperature is set to 70 °C, so electric heating will be activated when the temperature at the outlet of the second layer of the ETST (\(\:{t}_{2d}\)) falls below 70 °C. Once the heating duration of the municipal pipeline network exceeds 1440 h, the primary network ceases heat exchange, transitioning into independent peak-shaving operation mode 2. Figure 7 illustrates detailed flowcharts depicting the operational control strategies for each system component.

Mathematical model of the heat equipment

Due to the climate characteristics of the study region, DHPS utilizes indirect solar flat plate collectors. The collectors are characterized by their large aperture area and small footprint, simplicity in structure with no tracking requirements, low cost, and long operational lifespan. They are especially suitable for systems operating at low temperatures26. An indirect system requires an additional plate heat exchanger for insulation and antifreeze. The internal heat transfer medium consists of a 50% ethylene glycol (CH2OH)2 solution, with a freezing point of − 33.8 °C, ensuring liquid circulation even in winter outdoor temperatures. The necessary area for unit heat collection is about 10% greater than direct systems27. This study considers the complementary role of solar energy and AHP, with the collector area primarily determined by the \(\:{\eta\:}_{cd}\), AHP’s COP and θ. It is assumed that \(\:{\eta\:}_{cd}\) is the average heat collection rate of about 35% for a large collector in a severely cold region28, which is subsequently revised based on simulated actual values. The collector’s installation angle is set at 54° based on the local latitude of Changchun and the intended usage months. Throughout the research process, we maintained constant coefficients, disregarding factors such as dust accumulation on the collector surface, shading effects, and fluctuations in airflow during the heat collection process.

The expression for the collector area in the DHPS is as follow:

ETST is a crucial avenue for achieving peak shaving through load balancing and transfer at a low cost29. In light of the necessity for site renovations, this study selected a cylindrical electric heating water storage tank as the subject of its research. During the simulation, it is assumed that each node maintains a transient mass and energy balance. The tank is divided into five layers, each with a height of two meters, through which energy is exchanged between the layers via the flow of hot water. The entire operation ensures that the water volume within the tank remains stable, and supplementary water is provided to the system from the tank. The volume of the tank is primarily determined by the collector area design, with the calculation formula as follow:

Assuming ideal conditions for the AHP, where internal pressure losses are neglected, the working fluid remains in a saturated state during transport, and the system operates adiabatically without heat exchange with the surroundings. The study also assumes that the energy uptake and release of AHP is fully utilized. The unit maintains constant values for the inlet and outlet temperatures, with adjustments made solely on a volumetric basis. The specific operating points of the AHP are illustrated in Fig. 5, and the detailed calculations for the mathematical thermal balance model are as follows.

AHP follows mass balance through energy flow analysis and multi-criteria decision-making methods:

Overall energy balance equation for the unit:

Generator energy balance equation:

Condenser energy balance equation:

Evaporator energy balance equation:

Absorber energy balance equation:

The design flow calculation formula of the hot water circulation pump on the solar collector side is:

The formula for calculating the design area and logarithmic average temperature difference of the plate heat exchanger set by the indirect collector are:

The heating circulating water pump’s design flow rate between the AHP and the heat exchanger should meet the volume-variable peaking heat load required by the heat user. The design flow rate of the circulating water pump on the heating side is calculated as follow:

DHPS in this study bears varying loads depending on different peak shaving coefficients. Equipment capacities are reasonably set according to their corresponding operating conditions, as illustrated in Table 2. The overall specifications of the system resemble successfully implemented solar heating retrofit cases, which have demonstrated favorable operational outcomes30.

TRNSYS simulation

TRNSYS simulation process involves solving the differential equations corresponding to the various modules related to building energy31. The simulation requirements for DHPS entail assessing the energy consumption during peak shaving periods while meeting the thermal load, as well as evaluating the operating conditions and efficiencies of equipment on both the solar collection and peak shaving supply sides. This assessment is essential for determining the feasibility of system operation under different peak shaving coefficients. To ensure simulation accuracy, with a time step of 0.1 h. The main program, Simulation Studio, reads the initial settings, simulation start and end times, and convergence criteria for each device from the DECK file. The system built with the primary performance modules is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Range of peaking factor

The θ depends mainly on the efficiency of the primary heat source. Statistical analysis of boiler load rates during actual operation in 2021 showed that the longest operating time fell within the 50%–80% range, accounting for approximately 75% of the entire heating period. Studies on peak shaving of coal-fired units, also observed that the rated capacity of various types of units in different regions ranged from 50%–75%32. Additionally, emissions of certain pollutants exhibit a non-monotonic trend with temperature inside the furnace, which can be better utilized by maintaining an appropriate temperature range33. In consideration of both the scalability of heat load forecasting and the proactivity of peak shaving, the relationship between the operating conditions of the boiler unit and the peak-shaving coefficient range is established as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{\eta\:}_{b\:max}\) represents the optimal maximum operating rate of the boiler, set at 80%, \(\:{\eta\:}_{b\:min}\) represents the optimal minimum operating rate of the boiler, set at 50%, and ρ is the ratio of heat capacity between the heat exchange station and the boiler, which is set to 1/20 based on the data from this study. The variable θ is situated within the range of 0.20 to 0.51. However, determining the θ based solely on boiler efficiency equations can be challenging. It requires a multi-objective operating condition analysis of various system devices under different load proportions. Therefore, θ is set at integer gradients of 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 for further research and discussion. The load values within the collection area are multiplied by the corresponding θ to calculate the respective load values. Once verified as reasonable, these values can be input into TRNSYS to generate the hourly heat load dataset required for the DHPS. Finally, the optimal peak-shaving coefficient for the system is determined based on the simulation results of each group.

Comprehensive technical, environmental and economic assessment

To quantitatively assess the performance advantages of the renovated DHPS, we conducted a multi-criteria comparative analysis of energy, economic, and environmental factors under its optimal peak shaving coefficient, compared with a PCB carrying equivalent loads. Such evaluation framework is commonly employed in energy management and policy domains to accurately assess the comprehensive performance and sustainability of energy systems34. In this study, electricity consumption was quantified into coal consumption using the corresponding coefficient, enabling comparative calculations of the associated energy consumption and environmental impact.

Intuitive fuel consumption and primary energy ratio (PER) are used as comprehensive indicators to evaluate the degree of resource conservation in energy consumption. PER measures the efficiency of energy conversion and utilization processes35, the calculation formula is as follow:

The environmental impact of the distributed system was evaluated by measuring the reduction of emissions of CO2, SO2, NOx, and soot from combustion smoke. The corresponding reduction in emissions was calculated based on the emission equivalent of each pollutant and the total amount of coal saved.

Where \(\:{V}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the equivalent environmental technology post-treatment emission limits corresponding to CO2, SO2, NOx and soot emitted from 1 kg of combusted coal, which respectively are 2.556 kg, 0.077 kg, 0.038 kg and 0.697 kg36.

The economic benefits of the DHPS are assessed by computing the initial investment (\(\:{C}_{ii}\)) and the lifecycle operating costs (\(\:{C}_{OPE}\)). These costs include unit prices for electricity (\(\:{C}_{e}\)), water (\(\:{C}_{w}\)), depreciation and maintenance (\(\:{C}_{dep}\)), fuel consumption (\(\:{C}_{f}\)), waste disposal (\(\:{C}_{g}\)), and carbon tax (\(\:{C}_{car}\)). The financial recovery capability of the heating system is assessed using the financial model (Eq. 16) and the system’s static payback period (PBP).

Where λ is calculated separately for operating costs in conjunction with local energy contribution policies for different enterprises. This calculation is based on the fixed benchmark data from the case study year. Future system optimization research needs to predict the annual load, depreciation, and maintenance to obtain more accurate values.

Results and discussion

Model validation

TRNSYS simulation of distributed multi-energy systems has been validated against actual system operations, confirming its ability to effectively replicate the system’s operating conditions to a large extent. In studies involving solar-driven AHP and various other thermal systems, comparisons between simulated data and experimental data from test benches37, as well as field engineering cases38, have consistently shown that the numerical discrepancies obtained from TRNSYS simulations can be maintained within a favorable range of − 5% to 10%39.To ensure that the errors in system simulation fall within an acceptable and reliable range, we conducted a preliminary simulation of the municipal pipeline circulation system with constant flow rates. The adjustment curves for supply and return water temperatures were compared with the actual heating adjustment data from the power plant under study as shown in Fig. 9. While there were some discrepancies in the fluctuations between the manipulated values and the simulation results due to artificial intervention to broaden the supply and return water temperature differences in the primary network, other temperature data and trends were similar. The margin of error ranged from − 4.7 to 9.6%, thus confirming the validity of the heating simulation operating system.

Analysis of DHPS operating conditions at θ = 0.2/0.3/0.4/0.5

Heat collection efficiency of solar energy

Figure 10 illustrates the heat collection and efficiency of the solar flat plate collector under different peak shaving coefficients. The heat collection increases almost proportionally with the load and collector area. The highest average heat collection efficiency is 38.71% for θ = 0.2, followed by 37.88% for θ = 0.5. The study area chosen in this paper experiences short winter sunshine duration and snowfall, while the operational efficiency of the units is limited by temperature conditions. However, with rising outdoor temperature and increased irradiation, solar heat collection levels show an upward trend. The monthly average heat collection rates of θ = 0.2/0.5 can reach more than 45% of the efficient heat collection rates in winter, which is 49.11% and 48.68% respectively. This indicates that the solar collectors in the system can achieve operational efficiency adapted to extremely cold climates. It is also observed that the direct supply efficiency is even more satisfactory under low demand conditions with temperatures rising above − 10 °C. This conclusion is consistent with Li’s findings40, demonstrating that the system efficiency decrease is due to lower temperatures. Furthermore, Li’s research indicates that the coupled system can effectively mitigate the negative impacts on individual equipment caused by temperature fluctuations.

It can be seen from Fig. 10, this study identifies a fluctuating trend in heat collection efficiency with the increase of the peaking factor. This phenomenon occurs because, under normal temperature conditions, the efficiency of solar heat collection increases with the enlargement of the collector area. However, in extremely low temperatures, cold air significantly accelerates heat dissipation, leading to a substantial increase in heat loss41. As the collector area increases to a certain extent, the average heat loss per unit area will decrease. Therefore, finding the optimal collector size that balances heat collection and heat loss is crucial for enhancing solar heat collection efficiency in frigid climates. Implementing additional measures to mitigate heat loss in practical applications is recommended.

Variation of water temperature inside the storage tank and power consumption

The average water temperature inside the ETST fluctuates slightly around 70 °C during the initial two months to meet the driving temperature requirement, with minimal differences under any peaking factor as shown in Fig. 11. After the cessation of AHP operation, the temperature undergoes significant fluctuations at a consistent frequency across all factors due to the combined effects of changes in heat load and sufficient radiation leading to convective heat exchange. This fluctuation corresponds to the trend of the collector outlet temperature, as shown in Fig. 12 for θ = 0.5. Although the direct supply system provides the same load under any factor, the average water temperature inside the storage tank is highest at θ = 0.4. Under the same design formula for collector area and storage tank volume, a larger collector area results in a greater temperature difference between heat exchanges. This is because water at medium to low temperatures absorbs heat more readily from the collector, leading to higher temperatures. However, this effect may be limited, as larger tanks experience more heat loss from outdoor exchanges, necessitating more heat capture to maintain internal temperature. In summary, this indicates that the coupled system of solar collectors and storage tank is significantly influenced by radiation levels and ambient temperatures. Elmetwalli42 demonstrated that the tank volume loading rate can also be a significant factor influencing the efficacy of heat storage. Consequently, the optimization of volume should be a primary focus in subsequent studies.

In early March, when temperatures are low, the frequency of electric heating is higher. As the season progresses, the direct supply system can fully meet the heat demand of users, and the water tank only needs to activate auxiliary heating for a short time, as shown in Fig. 12. Among the different water volumes, θ = 0.5 has the highest power consumption, as shown in Fig. 13, but the high continuity of hot water large circulation compensates its shorter working duration of 1800.3 h. The increase in power consumption gradient is relatively consistent across different coefficients. θ = 0.5 shows the highest overall electricity consumption due to increased workload adjustments in all subsystems. However, its electricity consumption per unit heat load is the lowest, indicating that within a certain range, the system’s overall economy improves with increased heat load provision. It was also found that the electricity consumption for maintaining the water temperature at the tank outlet to meet the required driving temperature is relatively high. This is mainly because, with significant external heat exchange, setting a slightly higher outlet water temperature leads to greater heat consumption to maintain that temperature. Wang’s research43 on integrating thermal storage tanks in CHP units revealed that when a constant flow rate is maintained, an increase in outlet temperature results in a notable rise in both heat dissipation and thermal loss.

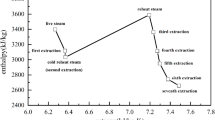

Performance of AHP

Considering typical heat losses, the composite AHP unit consumes only a small portion of the driving heat from the thermal storage tank, yet it can provide nearly five times the amount of heat to users and the power plant’s waste heat recovery system for each θ. In Fig. 14, the COP of the AHP under all peak shaving coefficient operating conditions remains consistently high, averaging between 1.70 and 1.80 throughout the operation period, except for slight fluctuations during initial startup. It is consistent with Dai’s study44 on solar and liquefied petroleum gas-driven absorption heat pumps in cold regions, which yielded an average COP of 1.66. This suggests that solar-driven AHPs can remain competitive even at low ambient temperatures, maintaining stable operation under any peak shaving coefficient. Units that bear larger loads show slight performance improvements. Therefore, in this system, higher power composite AHP units achieve better energy-saving efficiency at θ = 0.5. The superior heat absorption capability of the unit is not only due to its large capacity but also because the evaporator inlet temperature is slightly higher compared to other peak shaving states, thereby enhancing the solution’s ability inside the absorber to absorb refrigerant vapor. This observation also signifies a better match between its temperature conditions and thermal capacity45, indicating that larger capacity units perform better for DHPS.

Comparative assessment of the potential of DHPS and PCB

The results suggest that different components within the DHPS perform excellently across various peak shaving coefficients, with only minor differences. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of DHPS feasibility requires an entire lifecycle multi-objective comparative analysis with PCB that carries the same load under optimal θ condition. With the constraints of minimizing primary energy consumption and carbon emissions, calculations are based on the condition that a large thermal power plant requires approximately 0.30 kg of coal to generate 1 kWh of electricity and the heating value of coal for heating is around 40 kg/GJ46. After the total energy consumption to meet the thermal peak regulation in this area is offset by the part of the heat energy saved by the waste heat device, the coal consumption is the least when θ = 0.5, which means that the system performance of DHPS under this condition is the most advantageous.

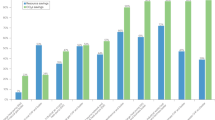

Comparative analysis of operational energy consumption

As shown in Table 3, DHPS can provide the same amount of heat load while consuming 40% less coal compared to PCB. Moreover, the majority of energy consumed in the portion of the load managed independently by DHPS is derived from electricity, which aligns perfectly with the current energy situation in northern China, where electricity supply exceeds demand. PCB’s PER is consistent with its thermal efficiency. The PER calculation for DHPS excludes the load provided by solar energy within the assessment framework because the reference system does not include renewable energy sources. The PER of DHPS is significantly higher than that of PCB. This indicates a substantial improvement in energy-saving potential for the heating system due to integrating primary energy with clean energy sources47, thereby surpassing its maximum contribution rate.

Comparative analysis of environmental emission reduction

Renewable energy systems offer significant advantages in various environmental domains48. Boiler rooms usually undergo flue gas treatment for SO2, NOX, and particulate matter emissions through small-scale desulfurization scrubbers, selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR), and dust removal bags before discharge. However, CO2 emissions in thermal power plants in northeastern China are rarely recycled, but efforts are being made to limit their volume. The heat exchange station introduces a new system that reduces coal consumption and corresponding pollutant emissions, as shown in the Table 4. Large-scale deployment of the DHPS could highlight substantial potential for low-carbon environmental protection.

Comparative analysis of whole-life economic benefits

Calculating the lifecycle costs and PBP of DHPS can effectively evaluate the relative attractiveness of projects49. Assuming a lifespan of 15 years for both systems, the coal-fired boiler shares 1/20 of the total initial investment cost of the purchase, design and installation of the entire device according to the heating radius, and the DHPS equipment is budgeted based on the current market prices. This study covers half of the heating season, during which the heat demand is approximately half of the overall demand, based on trends in heat exchange station loads. Therefore, the operating costs for the entire heating season can be calculated as twice the sum of the operating mentioned above costs. As shown in Fig. 15, since DHPS consists entirely of clean energy equipment with high technical requirements, the initial investment is higher when calculated based on current market prices. However, the two systems differ in operational costs. DHPS offers savings primarily in water replenishment, fuel costs, and carbon taxes. Water replenishment for PCB corresponds to the leakage loss, accounting for 8%–12% of the daily maximum hourly circulating water flow in the primary heat network, which is substantial and challenging to avoid. Given the historical price increase and future forecasts for coal, the depletion of fossil fuels will lead to higher premiums, significantly increasing PCB’s operational costs. In contrast, DHPS offers better returns.

Carbon taxes and trading are considered effective economic measures for reducing emissions50. Carbon tax refers to the fees imposed by government environmental departments on entities whose carbon emissions exceed designated industrial quotas. In contrast, while entities with low carbon emissions can sell surplus emission quotas in the carbon trading market to gain dividends51. Both systems currently require payment of carbon taxes when considering the entire research building’s heating area as a single emission unit. If carbon tax prices rise in pilot cities, it would provide significant advantages for DHPS’s operational quotas and stimulate the coal industry’s transition towards low-emission clean energy in severely cold regions. Furthermore, optimizing DHPS with a focus on low carbon emissions based on actual projects, makes it possible to achieve carbon profitability and demonstrate better economic performance. Currently, the most significant factor affecting economic benefits is the \(\:{C}_{e}\). With DHPS’s annual electricity cost at 1.5359 million CNY, its calculated PBP is 3.5 years, with a relatively short period indicating subsequent heating profitability. If the government, due to the new system’s utilization of excess electricity generated by CHP under a " heat-determined electricity generation” mode, introduces policies supporting clean energy heating that align with the energy characteristics of China’s cold regions in winter, reducing electricity prices to 0.275 CNY/kWh, operational costs could break even, as shown in Fig. 16. This would shorten the PBP to 1.9 years, further enhancing the economic feasibility of the DHPS.

Conclusions

This study proposes a novel distributed multi-energy coupling heating system, aiming to achieve deep and flexible peak shaving by integrating solar energy and AHP coupled system into the exchange station, followed by their alignment with the municipal pipeline network. The retrofitting scheme involves minor modifications that can be implemented quickly. Assessing the integrated feasibility of the system, we determined the optimal θ based on the TRNSYS simulation and conducted a comprehensive analysis of energy, environmental, and lifecycle economic sustainability by comparing it with PCB. The primary conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

In an appropriate peak-shaving range, the DHPS exhibits satisfactory heat collection rates and AHP’s COP under severe cold climate conditions, effectively meeting the energy demands characteristic of northern winters. When θ = 0.5, the system exhibits the most minor energy consumption, thus selected as the optimal peak shaving coefficient. During the study period, 2.65 × 106 kWh of waste heat was utilized. Simultaneously, putting multiple retrofitted heat exchange stations into operation improves the hydraulic conditions of the primary network and significantly enhances the efficiency of waste heat recovery from power plants.

-

(2)

DHPS is an energy-efficient and environmentally friendly system that provides high-quality heat energy during peak loads and directly supplies clean energy during low-load periods, reducing the operation of large-scale steam boilers. DHPS achieves a PER of 1.251, saving 162.28 tons of coal compared to the currently deployed PCB in the heating area. Correspondingly, it reduces the emissions of combustion pollutants after treatment by 416.94 tons of CO2, 0.251 tons of SO2, 1.211 tons of NOX, and 5.12 tons of particulate matter.

-

(3)

DHPS asset payback period is relatively optimal, and the optimized tariff makes the system more economically viable. Suppose the government environmental protection department implements preferential electricity policies for clean energy systems, reducing the electricity cost to 0.275 CNY. This would enable it to reach the breakeven point with the operating cost of PCB, thus shortening PBP. Higher primary energy prices or increased carbon tax rates in northern regions could narrow the operational cost gap even further, potentially leading to carbon tax revenues for the DHPS.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Xindong Wei, d2dbb412@eng.kitakyu-u.ac.jp], upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DHPS:

-

Distributed heating peak shaving system

- PCB:

-

Peak clipping boiler

- AHP:

-

Absorption heat pump unit

- PER:

-

Primary energy ratio

- PBP:

-

Static payback period

- CHP:

-

Combined heat and power

- IEA:

-

International energy agency

- DSM:

-

Demand side management

- COP:

-

Coefficient of performance

- CCHP:

-

Combined cooling, heating, and power

- ETST:

-

Electric thermal storage tank

- SNCR:

-

Selective non-catalytic reduction

- \(\:\theta\:\) :

-

Peak shaving coefficient

- \(\:\:\:\:\alpha\:\) :

-

Coal-to-power ratio

- \(\:{A}_{C}\) :

-

Total area of flat plate collector

- \(\:{Q}_{h}\) :

-

Average heat load

- J:

-

Total solar irradiance PV

- \(\:{A}_{S}\) :

-

Surface area of storage tank

- \(\:{t}_{a}\) :

-

Ambient temperature

- \(\:{X}_{L}\) :

-

Mass fraction of LiBr dilute solution

- \(\:{Q}_{G}\) :

-

Heat load of generator

- \(\:{Q}_{A}\) :

-

Heat load of absorber

- \(\:{h}_{x}\) :

-

Enthalpy of circulating mass at x state

- \(\:{G}_{S}\) :

-

Design flow rate of the collector pump

- F:

-

Calculated area of the heat exchanger

- \(\:{\Delta\:}{t}_{m}\) :

-

Logarithmic mean temperature difference

- \(\:{Q}_{T}\) :

-

Total design heat load for peak-shaving

- \(\:{Q}_{cons}\) :

-

Total power consumption of the DHPS

- Vi :

-

Emission of pollutants from1kg of coal

- \(\:{C}_{ii}\) :

-

Initial investment cost of the system

- \(\:{C}_{OPE}\) :

-

Total system operating costs

- \(\:{Q}_{n\:max}\) :

-

Average hourly maximum heat load

- \(\:{t}_{\text{i},\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\) :

-

Outlet temperature of each component

- \(\:{t}_{\text{i},\text{i}\text{n}}\) :

-

Inlet temperature of each component

- \(\:n\) :

-

Number of layers of storage tank

- \(\:{t}_{n}\) :

-

Average water temperature of n layer

- \(\:{t}_{nd}\) :

-

Bottom water temperature of n layer

- Δt:

-

Temperature difference

- \(\:{\eta\:}_{cd}\) :

-

Average thermal efficiency of collector

- \(\:{\eta\:}_{l}\) :

-

Heat loss rate of pipeline and tank

- τ:

-

Heat storage time

- \(\:{J}_{t}\) :

-

Average daily solar irradiation

- \(\:{C}_{w}\) :

-

Specific heat capacity of water

- f:

-

Solar energy local guarantee rate

- \(\:{M}_{S}\) :

-

Water storage tank mass volume

- \(\:{t}_{s}\) :

-

Average temperature of storage tank

- β:

-

Adaptive particle swarm optimization

- \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{i}\) :

-

Particle swarm optimization

- \(\:{t}_{\text{s}0}\) :

-

Initial average temperature of storage tank

- \(\:{U}_{S}\) :

-

Heat loss coefficient of storage tank

- \(\:{m}_{i}\) :

-

Mass flow rate of circulating at i state

- \(\:{X}_{H}\) :

-

Mass fraction of LiBr concentrated solution

- \(\:{Q}_{E}\) :

-

Heat load of evaporator

- \(\:{Q}_{C}\) :

-

Heat load of condenser

- D:

-

Cooling water mass flow rate

- \(\:g\) :

-

Flow rate per unit area of the collector

- K:

-

Heat transfer coefficient

- G:

-

Design flow rate of heating pump

- \(\:{Q}_{sz}\) :

-

Waste heat utilization

- Mi :

-

Emission reduction of various pollutants

- Qs :

-

Coal saving of distributed system

- \(\:{C}_{i}\) :

-

Unit price of each part of the costs

- \(\:{C}_{P\:}\) :

-

System heating revenue

- \(\:{Q}_{b}\) :

-

Boiler heating capacity

References

Ramzan, M. et al. Environmental cost of non-renewable energy and economic progress: Do ICT and financial development mitigate some burden?. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130066 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Multi-objective optimization of district heating systems with turbine-driving fans and pumps considering economic, exergic, and environmental aspects. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127694 (2023).

Nimsarkar A. D., Naidu H., Kokate P. A Novel Indoor Human Comfort Control Technique. 2022 Second International Conference on Power, Control and Computing Technologies (ICPC2T).1–6. https:/doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPC2T53885.2022.9776797 (2022).

International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2021.https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021(2021).

Hassan, M. A. et al. Evaluation of energy extraction of PV systems affected by environmental factors under real outdoor conditions. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 150, 715–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-04166-6 (2022).

Kinnon, M. M., Razeghi, G. & Samuelsen, S. The role of fuel cells in port microgrids to support sustainable goods movement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111226 (2021).

Yang, Z. et al. Research on the deep peak-shaving cost allocation mechanism considering the responsibility of the load side. Front. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1182620 (2023).

Liu, Z., Li, Y., Yang, G. & Wang, W. Development path of China’s gas power industry under the background of low-carbon transformation. Nat. Gas Ind.stry B. 8, 576–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ngib.2021.11.005 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Study on a novel district heating system combining clean coal-fired cogeneration with gas peak shaving. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112076 (2020).

Ma, T. et al. Design and performance analysis of deep peak shaving scheme for thermal power units based on high-temperature molten salt heat storage system. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129557 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Carbon reduction and flexibility enhancement of the CHP-based cascade heating system with integrated electric heat pump. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.116801 (2023).

Akbari, E., Mousavi Shabestari, S. F., Pirouzi, S. & Jadidoleslam, M. Network flexibility regulation by renewable energy hubs using flexibility pricing-based energy management. Renew. Energy. 206, 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.02.050 (2023).

Gyamfi, S., Diawuo, F. A., Asuamah, E. Y. & Effah, E. The role of demand-side management in sustainable energy sector development. Renew. Energy Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-88668-0.00010-3 (2022).

Guelpa, E. & Marincioni, L. Demand side management in district heating systems by innovative control. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116037 (2019).

Ju, Y., Jokisalo, J. & Kosonen, R. Peak shaving of a district heated office building with short-term thermal energy storage in Finland. Buildings. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030573 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Optimization study of a novel district heating system based on large temperature-difference heat exchange. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115517 (2022).

Song, Z. et al. Integration of geothermal water into secondary network by absorption-heat-pump-assisted district heating substations. Energy Build. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109403 (2019).

Wang, M., Huang, Y., An, Z. & Wei, C. Reforming the world’s largest heating system: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106417 (2023).

Al-Shahri, O. A. et al. Solar photovoltaic energy optimization methods, challenges and issues: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125465 (2021).

Su, Z. & Yang, L. Peak shaving strategy for renewable hybrid system driven by solar and radiative cooling integrating carbon capture and sewage treatment. Renew. Energy. 197, 1115–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.08.011 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Proposal and performance analysis of solar cogeneration system coupled with absorption heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.113873 (2019).

Dai, E., Jia, T. & Dai, Y. Theoretical and experimental investigation on a GAX-Based NH3-H2O absorption heat pump driven by parabolic trough solar collector. Solar Energy. 197, 498–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.01.011 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Exergo-economic assessment and sensitivity analysis of a solar-driven combined cooling, heating and power system with organic Rankine cycle and absorption heat pump. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120717 (2021).

Kadam, S. T. et al. Investigation of binary, ternary and quaternary mixtures across solution heat exchanger used in absorption refrigeration and process modifications to improve cycle performance. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117254 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation research on solar phase change heat Storage Kang. J. Univ. South China Sci. Technol. 38(1), 10–45 (2024).

Michael, J. J., Iniyan, S. & Goic, R. Flat plate solar photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems: A reference guide. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 51, 62–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.06.022 (2015).

Song, H., Zhao, P. & Shen, M. The application of solar air-source heat pump combined heating system in alpine region. District Heating 03, 16 (2023).

Cao, X., Dai, X. & Liu, J. Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy Build. 128, 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.06.089 (2016).

Sifnaios, I. et al. The impact of large-scale thermal energy storage in the energy system. Appl. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121663 (2023).

Fan, Z T. Shandong, China: 200,000 square meters of "solar + air energy community" heating, cost 13 yuan/m2 case. Available: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1695731931665685378 (2021).

Santos-Herrero, J. M., Lopez-Guede, J. M., Flores, A. I. & Zulueta, E. Energy and thermal modelling of an office building to develop an artificial neural networks model. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12924-9 (2022).

Gu, Y. et al. Overall review of peak shaving for coal-fired power units in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 723–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.052 (2016).

Ke, X. et al. Issues in deep peak regulation for circulating fluidized bed combustion: Variation of NO(x) emissions with boiler load. Environ. Pollut. 318, 120912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120912 (2023).

Prina, M. G. et al. Comparison methods of energy system frameworks, models and scenario results. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112719 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Comprehensive sustainability assessment and multi-objective optimization of a novel renewable energy driven multi-energy supply system. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.121461 (2024).

CRAES. GB13223-2011, Emission standard of air pollutants for thermal power plants. Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Beijing, China. https://english.mee.gov.cn/Resources/standards/Air_Environment/Emission_standard1/201201/W020110923324406748154.pdf (2011).

Marashli, A., Alfanatseh, E., Shalby, M. & Gomaa, M. R. Modelling single-effect of Lithium Bromide-Water (LiBr–H2O) driven by an evacuated solar tube collector in Ma’an city (Jordan) case study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2022.102239 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. Research on operation performance of multi-heat source complementary system of combined drying based on TRNSYS. Renew. Energy. 192, 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.05.001 (2022).

Shrivastava, R. L., Vinod, K. & Untawale, S. P. Modeling and simulation of solar water heater: A TRNSYS perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.005 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Technical and economic performance study on winter heating system of air source heat pump assisted solar evacuated tube water heater. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.119851 (2023).

Vérez, D. et al. Experimental study on two PCM macro-encapsulation designs in a thermal energy storage tank. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136171 (2021).

Elmetwalli, A. H., Darwesh, M. R., Amer, M. M. & Ghoname, M. S. Influence of solar radiation and surrounding temperature on heating water inside solar collector tank. J. Energy Stor. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.103648 (2022).

Wang, D., Han, X., Li, H. & Li, X. Modeling and control method of combined heat and power plant with integrated hot water storage tank. Appl. Therm. Eng. 226, 120314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120314 (2023).

Dai, E., Lin, M., Xia, J. & Dai, Y. Experimental investigation on a GAX based absorption heat pump driven by hybrid liquefied petroleum gas and solar energy. Solar Energy. 169, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.04.038 (2018).

Wu, Z. et al. Thermo-economic analysis of composite district heating substation with absorption heat pump. Applied Thermal Engineering. 166.

Kong, L. Hu, H. S., Song, G. Economic Analysis of Central Heating on Typical Climate Areas of China. Advanced Materials Research. 1008–1009: 1055–1060.

Ma, W. et al. Energy efficiency indicators for combined cooling, heating and power systems. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114187 (2021).

Sayed, E. T. et al. A critical review on environmental impacts of renewable energy systems and mitigation strategies: Wind, hydro, biomass and geothermal. Sci Total Environ. 766, 144505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144505 (2021).

Pathak, S. K. et al. Energy, exergy, economic and environmental analyses of solar air heating systems with and without thermal energy storage for sustainable development: A systematic review. J. Energy Stor. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.106521 (2023).

Fu, Y., Huang, G., Liu, L. & Zhai, M. A factorial CGE model for analyzing the impacts of stepped carbon tax on Chinese economy and carbon emission. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 143512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143512 (2021).

MEE. Carbon Credits Settlement Management Rules (Trial). Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. 000014672/2021-00427 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Tianyang Zhang: Conceptualization, investigation, writing, and modification. Bart Julien Dewancker: Conceptualization, review, and editing. Weijun Gao: Supervision. Xueyuan Zhao: Methodology. Xindong Wei: Data curation. Zu-An Liu: Validation. Weilun Chen / Qinfeng Zhao: Investigation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Tianyang Zhang] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Dewancker, B.J., Gao, W. et al. Research on performance and potential of distributed heating system for peak shaving with multi-energy resource. Sci Rep 14, 25350 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76108-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76108-3