Abstract

Bartonella are vector-borne gram-negative facultative intracellular bacteria that can infect a wide spectrum of mammals, and are recognized as emerging human pathogens. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and molecular characteristics of Bartonella infections in small mammals within the Qinghai Menyuan section of Qilian Mountain National Park, China. Small mammals were captured, and the liver, spleen and kidney were collected for Bartonella detection and identification using a combination of real-time PCR targeting the transfer-mRNA (ssrA) gene and followed by sequencing of the citrate synthase (gltA) gene. A total of 52 rodents were captured, and 36 rodents were positive for Bartonella, with a positivity rate of 69.23% (36/52). Bartonella was detected in Cricetulus longicaudatus, Microtus oeconomus, Mus musculus, and Ochotona cansus. The positivity rate was significantly different in the different habitats. Two Bartonella species were observed, including Bartonella grahamii and Bartonella heixiaziensis, and B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain in this area. Phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii mainly clustered into two clusters, which were closely related to the Apodemus isolates from China and Japan and the local plateau pika isolates, respectively. In addition, genetic polymorphism analysis showed that B. grahamii had high genetic diversity, and its haplotype had certain regional differences and host specificity. Overall, high prevalence of Bartonella in small mammals in the Qinghai Menyuan section of Qilian Mountain National Park. B. grahamii is the dominant strain with high genetic diversity and potential pathogenicity to humans, and corresponding control measures should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bartonella spp. are small, polymorphic, intracellular bacteria that are newly discovered ancient pathogens. During the First World War, an unknown disease plagued millions of soldiers, later known as “trench fever”, caused by Bartonella quintana1. To date, more than 40 of 100 species have been reported to infect a wide range of mammals, including rodents, cats, dogs, bats, ruminants, etc2. Bartonella can be transmitted by blood-sucking arthropods to different hosts such as fleas, mites, lice, and sandflies. People and animals may be infected with Bartonella through arthropod bites, or wounds in contact with pollutants containing pathogens3,4,5.

To date, more than 10 different Bartonella species have been shown to be associated with human diseases. The clinical manifestations of Bartonella infections vary. B. quintana6, transmitted by human lice, besides trench fever, it can also cause bacteremia, bacterial hemangioma, chronic lymphadenopathy, and endocarditis. B. bacilliformis7, transmitted by sandflies, is the pathogen that causes Carrion disease. B. henselae8, first isolated from a feverish patient infected with HIV in 1993, causes cat scratch disease (CSD). B. clarridgeiae9 is mainly associated with CSD, and its symptoms including headache, fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, and co-infection with B. henselae have been observed in cats10,11. In addition to these most common pathogenic Bartonella species, B. elizabethae12, B. koehlerae13, B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii14, B. elizabethae and B. alsatica can cause endocarditis, B. washoensis15 and B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis16 can cause myocarditis, B. rochalimae17, and B. tamiae18 can cause bacteremia, and B. grahamii19,20 can cause severe neuroretinitis. Generally, the symptoms are asymptomatic or mild in healthy people infected with Bartonella, but immunodeficient individuals show high morbidity and mortality21.

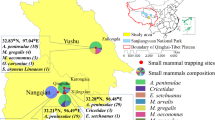

Among the reservoir hosts of Bartonella species, small mammals are considered important reservoirs, particularly rodents. Bartonella infection rates vary widely among rodents worldwide, ranging from 1 to 100%, with obvious regional difference22. Qilian Mountain National Park is located at the junction of the Gansu and Qinghai Provinces of China. It contains Menyuan County and Qilian County of the Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Tianjun County and Delingha City of the Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province. The Qinghai Province is rich in wild animal resources, especially rodent species23. Menyuan County is an important part of the Qilian Mountain National Park in Qinghai Province. In a previous study, we found that the Bartonella infection rate in the plateau pikas was 20.41% in Qilian County24. The prevalence of Bartonella in small mammals in Menyuan County is still unclear; therefore, it is necessary to study the prevalence of Bartonella in small mammals in this area, which is of great significance for the prevention and control of human bartonellosis when people engage in wild activity in this area.

Results

Animal collection

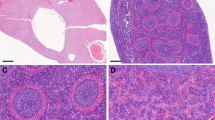

In total, 52 small mammals were captured and morphologically identified into five rodent species: Cricetulus longicaudatus (# = 31), Pitymys ierne (# = 6), Ochotona cansus (# = 6), Mus musculus (# = 5), and Microtus oeconomus (# = 4). The occupancy of each rodent species was 59.62% for C. longicaudatus, 11.54% for P. ierne, 11.54% for O. cansus, 9.62% for M. musculus, and 7.69% for M. oeconomus.

Bartonella infections

It was shown that 36 small mammals were positive for Bartonella, the positivity rate was 69.23% (36/52), among which the positivity rate was 93.55% (29/31) in C. longicaudatus, 75.00% (3/4) in M. oeconomus, 60.00% (3/5) in M. musculus, and 16.67% (1/6) in O. cansus. The difference in Bartonella positivity rate among the different small mammals was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The positivity rates in the liver, spleen, and kidney were 51.92% (27/51), 65.38% (34/51) and 59.62% (31/52), respectively. There was no significant difference in the positivity rate among different tissues (χ2 = 1.998, P = 0.368) (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Of the 52 small mammals, 33 were male and 19 were female. The positivity rates were 69.70% (23/33) and 68.40%(13/19), respectively, with no significant difference (χ2 = 0.009, P = 0.924). Twenty-four small mammals of three species were captured in the meadow, with a positivity rate of 66.67% (16/24) for Bartonella. Fourteen small mammals of five species were captured in the thicket, with a positivity rate of 42.86% (6/14). Fourteen small mammals of four species were captured in the farmlands, with a positivity rate of 100.00% (14/14). The difference in positivity rate in the different habitats was statistically significant (P = 0.003) (Table 2).

Identification of Bartonella species

Forty-two nucleotide sequences of gltA (represented by black dots in Fig. 2), including 14 sequences from the liver, 17 sequences from the spleen, and 11 sequences from the kidney. After BLAST and phylogenetic analysis, 41 sequences were classified as Bartonella grahamii (97.24–100% homology), obtained from 21 C. longicaudatus. One sequence from M. oeconomus clustered with Bartonella heixiaziensis (KJ175047, 99.39% homology).

To explore the origin of these B. grahamii sequences, we selected one sequence from each of the 21 C. longicaudatus in this study and compared it with B. grahamii strains from different regions and different hosts deposited in GenBank based on gltA gene. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using both maximum-likelihood and neighbor-joining methods, which showed similar results. B. grahamii sequences in this study mainly clustered into two clusters. The sequences CL06QHMY, CL17QHMY, CL43QHMY, and CL44QHMY from C. longicaudatus clustered with B. grahamii strains isolated from Chinese and Japanese Apodemus, whereas the other sequences clustered with B. grahamii isolated from the local plateau pika (Fig. 3).

Genetic diversity analysis

Genetic polymorphism analysis based on gltA gene sequence (326 bp) showed that 13 polymorphic loci (S = 13) and seven haplotypes (H = 7) of B. grahamii were found in this region. Haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.762 ± 0.065, average nucleotide difference (κ) was 3.762, and nucleotide diversity (π) was 0.01154.

Subsequently, gene polymorphism of gltA gene was analyzed by comparing 21 B. grahamii sequences obtained in this study with 77 B. grahamii sequences obtained from other regions of Qinghai Province24,25,26,27, including the Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Qilian County of Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. A total of 22 polymorphic loci (S = 22) and 19 haplotypes (H = 19) were identified. Haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.897 ± 0.014, average nucleotide difference (κ) was 4.854, and nucleotide diversity (π) was 0.01489.

DNA polymorphism analysis of gltA gene in B. grahamii was performed for different regions. The gltA gene polymorphism of B. grahamii was highest in the Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and lowest in the Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Hap 5, Hap 14 and Hap 17 were the main haplotypes in the Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture; Hap 2 was the main haplotype in the Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture; Hap 8 was the main haplotype in the Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture; and Hap 9 and Hap 14 were mainly found in the Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Table 3; Fig. 4). DNA polymorphism analysis of gltA gene of B. grahamii based on hosts showed that B. grahamii sequences from Apodemus peninsulae contained Hap 1–3, Cricetidae contained Hap 4–5, Ochotona curzoniae contained Hap 14–15, Microtus arvalis and Microtus oeconomus contained Hap 3, Microtus gregali contained Hap 6, Apodemus speciosus contained Hap 7, Mus musculus contained Hap 9, C. longicaudatus contained 13 haplotypes, indicating the highest genetic diversity of B. grahamii in C. longicaudatus (Table 4; Fig. 4). Twenty-one B. grahamii sequences obtained in this study were all derived from C. longicaudatus and contained seven haplotypes: Hap 5(8), Hap 8(2), Hap 10(1), Hap 16(1), Hap 17(7), Hap 18(1), and Hap 19(1) (Table S1).

Discussion

Bartonella spp. are distributed globally, and small mammals are among their most important natural hosts. Previous studies have shown that small mammals, especially rodents are the main hosts of B. grahamii28, B. elizabethae29 and B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis30, of which can cause diseases in humans. Since certain groups such as farmers, herders, field workers, and tourists may have contact opportunities, it is of great significance to explore Bartonella infections in the small mammals.

In this study, we found the Bartonella positivity rate in small mammals was 69.23% in Menyuan County, an important part of Qilian Mountain National Park, which was significantly higher than that in other areas of Qinghai Province (Qilian Mountains (20.41%)24, Qaidam Basin (38.61%)25, Sanjiangyuan area (30.10%)26, Maixiu National Forest Park (59.09%)27 and many provinces of China, such as Guangdong (6.42%)31, Shandong (8.38%32, 9.41%33), Fujian (14.86%)34, Xinjiang (16.67%)35, Shannxi (26.08%)36 and Shanxi (37.41%)37. The high positivity rate of Bartonella in this region may be related to two factors: (1) the infection rate of Bartonella was different among rodents in different regions, and the infection rate of Bartonella was higher among C. longicaudatus, which was the dominant rodent species in this region; and (2) compared to our previous studies, the detection method was different. In previous studies, we conducted Bartonella culture directly and performed PCR to identify suspicious colonies. In this study, PCR was used to screen for positive specimens. Bartonella is difficult to culture, and the positivity rate of PCR detection is higher than that of bacterial cultures. In addition, Bartonella positivity rates were the highest among small mammals in the farmland, suggesting that local people need to be alert to Bartonella infections in the farmland.

We obtained 42 nucleotide sequences of gltA gene of Bartonella from different tissues of 22 rodents, of which 41 were B. grahamii, derived from 21 C. longicaudatus, and one was B. haxiaziensis, derived from M. oeconomus. B. grahamii accounted for 95.35% of the total sequences, suggesting that it is the dominant endemic strain in this area. B. grahamii is one of the most prevalent Bartonella species in wild rodents and has been associated with human neuroretinitis19. Previous study revealed that B. grahamii showed a stronger geographic pattern38, and in this study, B. grahamii mainly clustered into two clusters; one cluster had higher homology with the B. grahamii isolates from Chinese and Japanese Apodemus, and the other cluster had higher homology with the local plateau pika isolates. This suggests that there may be different origins of B. grahamii in this area; however, further investigation is required to determine whether the pathogenicity differs.

A previous study showed rapid diversification of B. grahamii from wild rodents in China and Japan38. In total, 98 sequences of B. grahamii gltA gene were used for gene polymorphism analysis, including 21 B. grahamii sequences obtained in this study and 77 B. grahamii gltA gene sequences obtained from other regions of the Qinghai Province in our previous studies24,25,26,27. There were 19 haplotypes of gltA sequences for B. grahamii observed, with high genetic diversity (Hd = 0.897). It was greater than that of B. grahamii from the Heixiazi Island28 (Hd = 0.700, five strains) and the Shangdang Basin37 (Hd = 0.789, 30 sequences) in China. The genetic diversity of Bartonella shows regional differences, which may be related to different hosts. Bartonella evolves at different rates in different hosts and requires further study.

DNA polymorphism of B. grahamii gltA gene was the highest in the Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Among these nine haplotypes, Hap 5, Hap 14, and Hap 17 were the major haplotypes. In addition, B. grahamii sequences within Hap 1 and Hap 2 were from A. peninsulae, sequences within Hap 4 and Hap 5 were from Cricetidae, and sequences within Hap 14 and Hap 15 were from O. curzoniae, indicating that B. grahamii also has host specificity. Interestingly, B. grahamii sequences from C. longicaudatus contained multiple haplotypes and may have played an important role in the evolution of B. grahamii in this area, which requires further study.

Our study had some limitations. First, only 52 small mammals were collected in this study; the sample size was small, and C. longicaudatus was the dominant species, accounting for the vast majority. Except for C. longicaudatus, Bartonella positivity rates in other small mammals may be biased. Therefore, it is not suitable for comparing the positivity rates of small mammalian species. Second, some tissue samples did not contain a high quantity of bacteria; hence, not all PCR-positive samples were successfully sequenced. The sequencing success rate was 61.11% (22/36), which was higher than the 14.68% (16/109) and 17.61% (56/318) in Thailand and Lithuania, respectively, but lower than the 78.95% (45/57) in Tanzania39,40,41, which requires optimization in future studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a high Bartonella positivity rate of 69.23% was observed in small mammals in the Qinghai Menyuan Section of Qilian Mountain National Park of China. B. grahamii is a dominant epidemic strain that shows high genetic diversity and potential pathogenicity to humans. Our study will help to understand the prevalence and genetic diversity of Bartonella in small mammals in the Qinghai Menyuan Section of Qilian Mountain National Park and provide a scientific basis for local Bartonella control strategies.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No: ICDC-2015001) and Changzhi Medical College (No: DW2021052). All animals were treated according to the ARRIVE guidelines42 and 2016 Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education43. All efforts were made to minimize discomfort to the animals.

Animal collection

In July 2018, small mammals were captured using snap traps near the water inlet of the Yinda Jihuang Main Canal, located in Qingshizui Town, Menyuan County, Qinghai Province (37.28° N, 111.22° E). Captured rodents were placed in the transparent plastic box together with degreasing cotton soaked in isoflurane for anesthesia. Euthanasia was performed by cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia, which provide an efficient and quick death that minimizes pain. After euthanasia, the liver, spleen and kidney tissues of small mammals were then collected and stored at -80℃ for later use. Captured small mammals were identified by morphology and DNA barcoding based on the cytochrome C oxidase subunit I (CO I) gene.

Bartonella detection

The liver, spleen and kidney tissues of small mammals were used for Bartonella detection, and the transfer-mRNA (ssrA) gene was amplified by qPCR. Small mammals were considered to be infected with Bartonella when they were positive for ssrA gene in at least one tissue. DNA was extracted from approximately 10 mg of liver, spleen and kidney tissue according to the manufacturer’s protocols using the TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (TIANGEN Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., China). Real-time PCR was performed to detect Bartonella by targeting a fragment of 296 bp of ssrA gene according to a previous study44. Briefly, DNA amplification was performed in 20 µL mixtures containing 10 µL of HR qPCR Master Mix (Shanghai Huirui Bio-Tech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), 5 µL of RNase-Free water, 0.8 µL (10 µmol/L) of each primer and 0.4 µL (10 µmol/L) probe (ssrA-F: GCTATGGTAATAAATGGACAATGAAATAA; ssrA-R: GCTTCTGTTGCCAGGTG; ssrA-P: FAM-ACCCCGCTTAAACCTGCGACG-BHQ1)45, and 3 µL of DNA template. The PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: one cycle for 5 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles for 15 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60 °C, and positive and negative controls were set. Samples with Cq ≤ 35 were considered positive for amplification.

Bartonella sequencing

For ssrA-positive samples, the Bartonella citrate synthase (gltA) gene was amplified in 20 µL reaction mixtures containing 10 µL 2×EasyTaq PCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, China), 6.4 µL RNase-Free water, 0.8 µL (10 µmol/L) of each primerr (BhCS781.p: GGGGACCAGCTCATGGTGG; BhCS1137.n: AATGCAAAAAGAACAGTAAACA)46, and 2 µL of DNA template. gltA amplification was performed under the following conditions: one cycle for 5 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles for 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C; and a final extension for 10 min at 72 °C. Next, PCR products of 379 bp were identified by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and then sent to Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for sequencing.

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers: PP501477-PP501518). The nucleotide sequence homology was blasted against reported Bartonella species sequences in the GenBank using the BLAST program at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W. Phylogenetic trees were created using the maximum-likelihood method with MEGA version 7.0, based on the nucleotide Kimura 2-parameter model, and bootstrap values were calculated with 1000 replicates47,48. Brucella abortus was used as the outgroup.

The Bartonella grahamii sequences obtained in this study were combined with B. grahamii sequence collected in GenBank from different hosts in different regions to construct phylogenetic tree by using maximum-likelihood method and neighbor- joining method for traceability analysis. Based on the nucleotide Kimura 2-parameter model, the phylogenetic tree was constructed with 1000 repeated calculations of bootstrap value, and another Bartonella in this study were selected as the outgroup.

Genetic diversity analysis

Polymorphism within gltA gene of Bartonella was high28, so we selected this gene to analyze gene polymorphisms in B. grahamii. Bartonella-positive sequences were analyzed for polymorphisms based on the number of polymorphic sites (S), the number of haplotypes (H), nucleotide diversity (π), average number of nucleotide differences (κ) and haplotype diversity (Hd) using DNASP 6.12.03. Sequences were analyzed based on a median-joining network using Population Analysis with Reticulate Trees (PopART) software version 1.7 (http://popart.otago.ac.nz/index.shtml) with the default setting (epsilon = 0). Accession numbers of Bartonella strains obtained in our previous studies are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Statistical analysis

SPSS22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Qualitative data are presented as n (%). The positivity rates of Bartonella in different tissues and sexes of small mammals were analyzed using chi-square test, and the positivity rates in different habitats and species of small mammals were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. All genetic sequences generated in this study are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and available under accession numbers: PP501477-PP501518. Please contact the corresponding author if someone wants to request the data from this study.

References

Venning, J. A. The etiology of disordered action of the heart: A report on 7,803 cases. Br. Med. J. 2, 337–339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.3063.337 (1919).

Huang, K. et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in China and St. Kitts. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 3209013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3209013 (2019).

Nasereddin, A. et al. Bartonella species in fleas from Palestinian territories: Prevalence and genetic diversity. J. Vector Ecol. 39, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvec.12100 (2014).

Breitschwerdt, E. B. & Kordick, D. L. Bartonella infection in animals: Carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.13.3.428 (2000).

Tsai, Y. L., Chang, C. C., Chuang, S. T. & Chomel, B. B. Bartonella species and their ectoparasites: Selective host adaptation or strain selection between the vector and the mammalian host?. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2011.04.005 (2011).

Arvand, M., Raoult, D. & Feil, E. J. Multi-locus sequence typing of a geographically and temporally diverse sample of the highly clonal human pathogen Bartonella quintana. PLoS One 5, e9765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009765 (2010).

Minnick, M. F. et al. Oroya fever and verruga peruana: Bartonelloses unique to South America. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2919. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002919 (2014).

Chaudhry, R. et al. Bartonella henselae infection in diverse clinical conditions in a tertiary care hospital in north India. Indian J. Med. Res. 147, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1932_16 (2018).

Kordick, D. L. et al. Bartonella clarridgeiae, a newly recognized zoonotic pathogen causing inoculation papules, fever, and lymphadenopathy (cat scratch disease). J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 1813–1818. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.35.7.1813-1818.1997 (1997).

Margileth, A. M. & Baehren, D. F. Chest-wall abscess due to cat-scratch disease (CSD) in an adult with antibodies to Bartonella clarridgeiae: Case report and review of the thoracopulmonary manifestations of CSD. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27, 353–357. https://doi.org/10.1086/514671 (1998).

Bai, Y. et al. Coexistence of Bartonella henselae and B. clarridgeiae in populations of cats and their fleas in Guatemala. J. Vector Ecol. 40, 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvec.12171 (2015).

Daly, J. S. et al. Rochalimaea elizabethae sp. nov. isolated from a patient with endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31, 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.31.4.872-881.1993 (1993).

Avidor, B. et al. Bartonella koehlerae, a new cat-associated agent of culture-negative human endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 3462–3468. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.42.8.3462-3468.2004 (2004).

Breitschwerdt, E. B. et al. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and Bartonella henselae bacteremia in a father and daughter with neurological disease. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-3-29 (2010).

Kosoy, M., Murray, M., Gilmore, R. D. Jr., Bai, Y. & Gage, K. L. Bartonella strains from ground squirrels are identical to Bartonella Washoensis isolated from a human patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.2.645-650.2003 (2003).

Fenollar, F., Sire, S. & Raoult, D. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis as an agent of blood culture-negative endocarditis in a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 945–947. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.2.945-947.2005 (2005).

Chomel, B. B. et al. Dogs are more permissive than cats or guinea pigs to experimental infection with a human isolate of Bartonella rochalimae. Vet. Res. 40, 27. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres/2009010 (2009).

Colton, L., Zeidner, N., Lynch, T. & Kosoy, M. Y. Human isolates of Bartonella tamiae induce pathology in experimentally inoculated immunocompetent mice. BMC Infect. Dis. 10, 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-229 (2010).

Kerkhoff, F. T., Bergmans, A. M., van Der Zee, A. & Rothova, A. Demonstration of Bartonella grahamii DNA in ocular fluids of a patient with neuroretinitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 4034–4038. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.37.12.4034-4038.1999 (1999).

Oksi, J. et al. Cat scratch disease caused by Bartonella grahamii in an immunocompromised patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 2781–2784. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00910-13 (2013).

Mosepele, M., Mazo, D. & Cohn, J. Bartonella infection in immunocompromised hosts: Immunology of vascular infection and vasoproliferation. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/612809 (2012).

Gutierrez, R. et al. Bartonella infection in rodents and their flea ectoparasites: An overview. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 15, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2014.1606 (2015).

Li, H. L. et al. Investigation of geographical distribution pattern of rodents in Qinghai Province, China. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control. 24, 418–421. https://doi.org/10.11853/j.issn.1003.4692.2013.05.011 (2013).

Rao, H. X. et al. Bartonella species detected in the Plateau pikas (Ochotona Curzoiae) from Qinghai Plateau in China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 28, 674–678. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2015.094 (2015).

Rao, H. et al. Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China. Sci. Rep. 11, 1735. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81508-w (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Detection and genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals from the central region of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Sci. Rep. 12, 6996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11419-x (2022).

Rao, H. X., Yu, J., Li, S. J., Son, X. P. & Li, D. M. Gene polymorphisms of Bartonella species in small mammals in Maixiu National Forest Park in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control. 32, 398–403. https://doi.org/10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2021.04.003 (2021).

Li, D. M. et al. High prevalence and genetic heterogeneity of rodent-borne Bartonella species on Heixiazi Island, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 7981–7992. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02041-15 (2015).

Tay, S. T., Kho, K. L., Wee, W. Y. & Choo, S. W. Whole-genome sequence analysis and exploration of the zoonotic potential of a rat-borne Bartonella elizabethae. Acta Trop. 155, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.11.019 (2016).

Schulte Fischedick, F. B. et al. Identification of Bartonella Species isolated from rodents from Yucatan, Mexico, and isolation of Bartonella vinsonii subsp. Yucatanensis subsp. Nov. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 16, 636–642. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2016.1981 (2016).

Yao, X. Y. et al. Epidemiology and genetic diversity of Bartonella in rodents in urban areas of Guangzhou, southern China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 942587. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.942587 (2022).

Qin, X. R., Liu, J. W., Yu, H. & Yu, X. J. Bartonella species detected in rodents from Eastern China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 19, 810–814. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2018.2410 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Host specificity and genetic diversity of Bartonella in rodents and shrews from Eastern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, 3906–3916. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14761 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Epidemiological characteristics and genetic diversity of Bartonella species in rodents from southeastern China. Zoonoses Public. Health 69, 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12912 (2022).

Xu, A. L. et al. Bartonella prevalence and genome sequences in rodents in some regions of Xinjiang, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 89, e0196422. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01964-22 (2023).

An, C. H. et al. Bartonella species investigated among rodents from Shaanxi Province of China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 33, 201–205. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2020.028 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. Prevalence and diversity of small rodent-associated Bartonella species in Shangdang Basin, China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010446. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010446 (2022).

Berglund, E. C. et al. Rapid diversification by recombination in Bartonella grahamii from wild rodents in Asia contrasts with low levels of genomic divergence in Northern Europe and America. Mol. Ecol. 19, 2241–2255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04646.x (2010).

Broome, C. V. Epidemiology of toxic shock syndrome in the United States: Overview. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl 1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_1.s14 (1989).

Mardosaite-Busaitiene, D. et al. Prevalence and diversity of Bartonella species in small rodents from coastal and continental areas. Sci. Rep. 9, 12349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48715-y (2019).

Theonest, N. O. et al. Molecular detection and genetic characterization of Bartonella species from rodents and their associated ectoparasites from northern Tanzania. PLoS One 14, e0223667. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223667 (2019).

Percie du Sert. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 (2020).

Sikes, R. S. & Animal, C. Use Committee of the American Society of, M. 2016 guidelines of the American Society of mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. J. Mammal 97, 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyw078 (2016).

Li, D. et al. An epidemiologic investigation of rodent-borne pathogens in some suburban areas of Beijing, China. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control 30, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2019.01.003 (2019).

Diaz, M. H., Bai, Y., Malania, L., Winchell, J. M. & Kosoy, M. Y. Development of a novel genus-specific real-time PCR assay for detection and differentiation of Bartonella species and genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1645–1649. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.06621-11 (2012).

Norman, A. F., Regnery, R., Jameson, P., Greene, C. & Krause, D. C. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33, 1797–1803. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.33.7.1797-1803.1995 (1995).

Bai, Y. et al. Global distribution of Bartonella infections in domestic bovine and characterization of Bartonella bovis strains using multi-locus sequence typing. PLoS One 8, e80894. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080894 (2013).

Huang, R. et al. Bartonella quintana infections in captive monkeys, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 1707–1709. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1709.110133 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to Qinghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention employees, who participated in the specimen collection.

Funding

The present work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province of China (20210302124299, 202303021221180), Academic technology leader program of Changzhi Medical College (XS202103). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.L. and J.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. H.X.R., Y.P.L., J.R.N. and J.C. performed the experiments. J.Y. and H.X.R. analyzed the data. H.X.R. and D.M.L. contributed samples. H.X.R., D.M.L.and J.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All the authors consent to publish the article in its present form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, H., Liu, Y., Cui, J. et al. Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qinghai Menyuan section of Qilian Mountain National Park, China. Sci Rep 14, 25285 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76222-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76222-2