Abstract

Acid or base modification of biochars has shown promise for enhancing the immobilization of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) such as cadmium (Cd) in contaminated soils. However, limited information is available on the interaction between soil textural classes and modified biochar application for Cd stabilization in contaminated calcareous soils. Therefore, the objective of the study was to examine the extent of Cd immobilization in contaminated calcareous soils with diverse textural classes, utilizing both acid (HNO3) and alkali (NaOH) modified and unmodified biochars derived from sheep manure and rice husk residues. The modified or unmodified biochars were applied at a rate of 2% (w/w) to Cd-contaminated silty clay loam, loam, and sandy loam soils, followed by a 90-day incubation at field water capacity. Sequential extraction and EDTA-release kinetics studies were used to assess the effect of the treatments on the extent and mechanisms of Cd immobilization. Among the treatments, acid-modified manure biochar was most effective at reducing water soluble and exchangeable Cd fractions (-20.5%), by converting them into metal oxide and organic matter bound fractions. This effectiveness was primarily attributed to the significant increase in surface oxygen functional groups in the acid-modified biochar which could promote Cd complexation. However, the acid-modified manure biochar released more immobilized Cd during EDTA extraction than the base-modified manure biochar, suggesting that EDTA extraction of R-O-Cd complexes was easier than extracting Cd associated with insoluble compounds. This difference was likely due to the acidic pH and lower ash content of the acid-modified biochars compared to the base-modified manure biochars. Additionally, the extent of Cd immobilization was lower in sandy loam soil, highlighting the importance of immobilizing Cd in light-textured soils to prevent its transfer to organisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) exhibit high toxicity and are resistant to biodegradation, gradually accumulating within the food chain. Even at low concentrations, their presence in water or soil can pose long-term environmental and human risks. Increased industrialization and conventional agricultural practices over recent decades have resulted in significant soil pollution by PTEs. Cadmium (Cd), an unnecessary element for living organisms, is known to be carcinogenic at low levels and is commonly encountered in industrial discharges stemming from activities like mining, smelting, electroplating, and petrochemical manufacturing1,2. The soil Cd concentration threshold that leads to biomass reduction in agricultural plants has been documented to range from 5 to 15 mg kg−1 of soil3. The remediation of soils contaminated with Cd is crucial for safeguarding the environment and protect human health4,5.

Numerous physical and chemical techniques exist for remediating soils contaminated with PTEs, offering a wide array of effective options. However, many of these methods tend to be costly and are better suited for remediation at smaller-scale sites. Among the various promising remediation approaches, in situ immobilization stands out. This method involves introducing a remedial agent into the contaminated soil to stabilize PTEs, thereby reducing the exposure of plants (receptors) to these harmful substances without causing any adverse effects. By converting PTEs into less soluble or toxic forms, this technique significantly diminishes the risk associated with soils contaminated with PTEs6.

Biochar is recalcitrant, carbon-rich soil amendment which is derived from the pyrolysis of biomass7. It possesses exceptional adsorption properties due to its porous structure and diverse functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and phenolic compounds7,8. This enables biochar to effectively capture both organic and inorganic substances present in the environment. When it comes to PTEs such as As, Ni, Pb, and Cd, biochar can immobilize them in soil or water through processes such as ion exchange, complexation with available functional groups, physical adsorption, and surface precipitation7,8. Moreover, the physical characteristics of biochar, including its morphology and surface area, also play a role in the adsorption of PTEs to some extent. It is worth noting that these properties can vary based on the production conditions and the raw materials used in the biochar manufacturing process6,9. Various techniques have been employed to enhance the adsorption capacity of biochars, including magnetization, nanoparticle incorporation, coating modifications, and alkalinity and acidity treatments. Among these methods, alkaline activation and chemical oxidation have proven to be effective and suitable approaches for augmenting the porous structure and oxygenated functional groups of biochar. These modifications enhance the adsorption properties of biochar specifically for soil PTEs7,10,11. For example, when cotton residue biochar underwent oxidation using nitric acid, the resulting biochar exhibited an abundance of carboxyl groups and demonstrated an enhanced capacity to retain Pb, Cu, and Zn compared to the original biochar12. In a separate investigation, the utilization of HNO3-modified wheat straw biochar in a contaminated soil resulted in a 2-10-folds increase in Cd2+ adsorption capacity compared to unmodified biochar. This improvement was attributed to the increased specific surface area, which increased by 1.5–6.5 times, as well as the higher abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups, which increased by 4.5–22.1% 13.

A variety of methods is employed to assess the efficacy of biochar application in stabilizing PTEs in contaminated soils. These methods include sequential extraction, washing, and adsorption-desorption experiments. Sequential extraction techniques are particularly useful for monitoring the stabilization process of PTEs in contaminated soil when amendments like biochar, compost, and animal manure are introduced. These methods categorize elements in the soil into soluble and exchangeable, carbonate, organic, oxide, and residual forms. The soluble and exchangeable fraction is considered the most dynamic and bioavailable form of the elements in the soil, while the residual form represents the most stable state, associated with the internal mineral network. Other forms of the elements in the soil hold the potential for plant uptake, contingent upon the physicochemical conditions of the soil. Additionally, the mobility and toxicity of an element in the soil are influenced by its surface adsorption and release characteristics. A higher release rate of an element from the soil suggests increased mobility and toxicity6,14,15.

In this study, we hypothesized that soil textural classes may impact the chemical fractions of soil-bound PTEs and their adsorption-desorption properties, due to variations in clay content and water retention capacity. There is a significant lack of literature regarding the interaction between soil textural classes and modified biochar application for Cd stabilization in contaminated calcareous soils. Furthermore, we aim to investigate whether biochars modified by acid and base treatments utilize similar mechanisms in stabilizing and releasing Cd from contaminated calcareous soils across different textural classes. Additionally, we seek to determine whether light-textured polluted calcareous soils require more modification compared to heavy-textured soils. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to examine the immobilization and desorption of soil Cd in a contaminated calcareous soil with diverse textural classes, utilizing both acid and alkali modified and unmodified biochars derived from agricultural residues.

Materials and methods

Soil sampling and polluting

A sufficient quantity of soil was collected from the top layer (0–20 cm) of a highly textured soil with a clay content exceeding 30%, which was located at Arsanjan region, Fars province, southern Iran (29°50′13″ N 53°06′19″ E, Elevation 1638 m) (Table 1). After air-drying and passing the soil through a 2 mm sieve, various chemical and physical characteristics of the soil were measured using standard laboratory methods. Sand, silt and clay content of the soil were determined by the hydrometer method16. Soil pH and EC were measured using a saturated paste17, while organic matter was assessed using the Walkley-Black procedure18. Calcium carbonate equivalent (CCE) was quantified through acid neutralization19, while cation exchange capacity was evaluated using 1 M ammonium acetate method20. Available Cd was determined through DPTA extraction21. Two soil samples with lighter textures were produced by adding sand to the initial soil to achieve samples with loam and sandy loam texture classes (Table 1). Plastic boxes were filled with 100 g each of the three soil textural classes. A 50 ml aqueous solution containing Cd, prepared from distilled water and CdCl2 salt, was added to each sample and thoroughly mixed, resulting in an addition of 100 mg of Cd per kilogram of soil. The samples were then left to dry at room temperature. Once dried, the samples were moistened to field capacity level using distilled water by weighing. They were once again left to dry. This process of successive wetting and drying was repeated three times consecutively over a 60-day period at a temperature of 25 ± 2 ºC to ensure thorough mixing of Cd with the soil, achieve an equilibrium state, and simulate field conditions22.

Biochar production and its characteristics

Biochar samples were produced using a slow pyrolysis method in an electric oven, with a heating rate of 5 °C per minute. The raw materials, rice husk and sheep manure, were placed inside a glass jar, and the lid was covered with a double-layer of aluminum foil to create limited oxygen conditions. The pyrolysis process was conducted at a temperature of 500 °C for a duration of 4 h9. Before use, the produced biochars were passed through a 0.5 mm sieve to ensure uniformity. Biochar pH and EC were determined in a 1:20 deionized water suspension23, while CEC was determined using the method of Abdelhafez, et al.24. Biochar total C, N and H contents were determined by elemental analyzer (ThermoFinnigan Flash EA 1112 Series, Thermoscientific, USA). Biochar moisture and ash content were determined by heating in an oven, while the O + S content was calculated by subtraction of C, N, H, ash and moisture content from total biochar mass25. Biochar total Cd content was determined by combustion and dissolution of the ash in 2 M HCl6. The Cd content in the acid solution was determined using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) (PG 990, PG Instruments Ltd., UK). For the analysis of functional groups and surface morphology, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Shimadzu DR-8001) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (TESCAN-Vega3, Czech Republic) were utilized, respectively.

Modification of the biochars

To modify biochars using sodium hydroxide, a mixture was prepared by combining the biochar with 2 M sodium hydroxide at a ratio of 1:5 (biochar: sodium hydroxide) following the method of Chen, et al.4. The mixture was then placed in a polyethylene bottle and shaken using a mechanical shaker at a speed of 30 rpm for a duration of 12 h at a temperature of 65ºC. Once cooled to ambient temperature, the mixture was filtered, and the sediment containing the modified biochar was collected. The collected biochar was further washed with distilled water and subsequently dried at 105ºC.

The method of Jin, et al.26 was employed to modify biochar using nitric acid. Ten grams of biochar were mixed with 300 mL of a 25% nitric acid solution and subjected to a 4-hour treatment at a temperature of 90ºC. Following the treatment, the mixture was cooled, filtered, and washed with distilled water. The resulting modified biochar was then dried at a temperature of 105ºC.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

A factorial experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design with three replications. The experiment involved two factors. The first factor consisted of different biochars, including a control (without biochar), rice husk biochar (R), sheep manure biochar (S), and their respective modified biochars, each at a level of 2% (w/w). The second factor consisted of soil textural classes, categorized as silty clay loam (H), loam (M), and sandy loam (L). The collected data were analyzed statistically using MSTATC software. Means were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of 5%.

Soil incubation experiment

Contaminated soil samples weighing 100 g each were placed in plastic containers and mixed with biochars based on the experimental design. Subsequently, the moisture content of the soil samples was adjusted to approximately field capacity by adding distilled water. The samples were then kept at room temperature for a duration of 90 days. Throughout the incubation period, the soil moisture content was carefully regulated to remain at the field capacity. This was achieved by utilizing distilled water and employing a daily weighing method to monitor and adjust the moisture levels as needed. After the completion of the incubation period, the air-dried soil samples were carefully transferred to the laboratory for chemical analysis. Before analysis, the samples were passed through a 2 mm sieve to remove any coarse particles or debris.

Sequential extraction procedure

The method developed by Salbu and Krekling27 was employed to fractionate soil Cd into five distinct forms. These forms included soluble and exchangeable (Cd-WsEx), bound to carbonate (Cd-Car), bound to organic materials (Cd-OM), bound to iron and manganese oxide (Cd-FeMnOx), and the residual fraction (Cd-Res). The Cd-Res fraction was determined by calculating the difference between the total soil Cd content and the combined amounts of the other forms. The measurement of total soil Cd content was carried out using the method described by Sposito, et al.28.

Cadmium release kinetics

The kinetics of Cd release were investigated using the EDTA extractant method developed by Dang, et al.29. In each treatment, 25 mL of EDTA solution with a pH of 7.0 was added to 5 g of soil. The soil-EDTA mixtures were shaken at a constant temperature of 25 °C for different time intervals: 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 360, 720, and 1440 min. After shaking, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant fluid was immediately filtered using Whatman 42 filter paper, and the concentration of Cd in the filtered solution was determined using atomic absorption spectroscopy (ABS). Subsequently, the obtained Cd release data were fitted to a two-first order reaction kinetic model proposed by Santos, et al.30. This kinetic model divides the Cd release into three components: G1, G2, and G3.

In the proposed model, the amount of Cd released at time t (mg kg−1) is represented by q. The labile Cd or easily extractable component is denoted by G1 (mg kg−1), which is associated with the release rate coefficient M1. G2 (mg kg− 1) represents the less labile Cd or less extractable fraction, connected to the release rate coefficient M2. G3 (mg kg−1) corresponds to the non-extractable form, which is determined by calculating the difference between the total Cd and the sum of G1 and G2 components. To assess the model’s performance, the standard error of estimate (SEE) and coefficient of explanation (r2) were evaluated. The parameters associated with the two-first order reaction kinetic model were extracted by nonlinear fitting of the Cd release data using Sigma plot 12.0 computer software.

Results and discussion

Soil characteristics

Some physicochemical properties of the three soil samples are given in Table 1. The soil samples were alkaline and calcareous, but non-saline in nature (EC < 4 dS m−1). The highest organic matter, clay and cation exchange capacity (CEC) values were associated with the silty clay loam textural class. The total Cd in all the soils was lower than the detection limit by AAS.

Chemical composition of the biochars

The chemical properties of acid- and base-modified and unmodified biochars are shown in Table 2. The unmodified rice husk (R) and sheep manure biochars (S) were alkaline in nature and contained a high proportion of ash (45–60%). Acid treatment of the biochars (RA and SA) resulted in a substantial decline in both the pH and ash content of the biochars. Furthermore, acid treatment led to a substantial increase in the O + S: C mole ratio and CEC, indicating an increase in oxygen- containing functional groups. Base treatment (RB and SB) also resulted in a decrease in biochar pH and ash content and an increase in the O + S: C mole ratio; however, it had a less pronounced effect than the acid treatment.

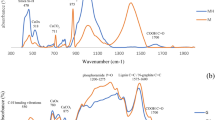

FTIR and SEM of the biochars

The FTIR spectra of the acid and base-modified and unmodified biochars are shown in Fig. 1. All of the biochars contained organic functional groups associated with cellulose and lignin25. The unmodified biochars also contained silica, indicated by the strong absorption bands at 470, 800 and 1100 cm[− 131. The manure biochar (S) contained a higher content of calcium carbonate than the rice husk biochar (R), indicated by the sharp absorption band at 875 cm[− 132. Acid and base treatment of the biochars resulted in a significant increase in the carboxyl group absorption bands at 1690–1720 cm− 1, which was more pronounced in the acid treated biochars (RA and SA). This is in agreement with the O + S: C mole ratio data (Table 1) which indicated that acid modification resulted in a greater increase in oxygen-containing functional groups. Similar to the present study, Peiris, et al.33 conducted an experiment where tea waste biochar was modified using nitric and sulfuric acids. They observed that in the acid-modified biochars, a prominent peak associated with carbonyl stretching emerged around 1690–1720 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum indicating the introduction of carboxylic acid functional groups. The nitric acid modification process resulted in the formation of new oxygenated surface functional groups through the oxidative ring opening of aromatic rings (via electrophilic addition reactions) and the additional oxidation of existing oxygenated surface functional groups. Acid treatment of sheep manure biochar (SA) also resulted in a loss of the sharp absorption band associated with calcium carbonate (875 cm−1).

The SEM images of the R, S, RA and SA biochars are shown in Fig. 2. The images show that the microporous structures were significantly increased as a result of the acid and base treatment. This was also observed by Bashir, et al.34 who investigated the structural porous of KOH-modified rice straw biochar with SEM.

Cadmium chemical fractions as affected by biochars and soil textural classes

The main effects of treatments and their interactions on the soil Cd chemical fractions (except the Cd-Car fraction) were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (data not shown). The soil Cd in the WsEx fraction was significantly reduced by the addition of all the biochar treatments compared to the control, with the greatest decrease in the SA treatment of 19.5% (Table 3). In general, the modified-sheep manure biochars (SA and SB) were more effective in decreasing soil Cd associated with the WsEx fraction than the modified-rice husk biochars (RA and RB) (Table 3). This may be due to the higher ash contents and CEC values of the modified sheep manure biochars (Table 2), which promote Cd precipitation reactions8,35. The application of SB resulted in a significant increase in soil pH (by 0.30 units), whereas SA resulted in a significant decrease in soil pH (by 0.23 units) compared to the control (data not shown). However, the soil Cd-WsEx concentration was decreased to a greater extent by SA than SB (Table 3). As shown in Table 2, modification of the biochars by NaOH and HNO3 caused a considerable increase in the CEC content and O/C mole ratios. This was also confirmed by the dramatic increase in COOH peak intensity, especially in the acid modified biochars (Fig. 1). This indicates that the main mechanism associated with the reduction of Cd-WsEx content in soils amended with SA is complexation. In agreement, Liu, et al.36 found that the adsorption of Cd by biochar exhibited a positive correlation with the biochar O/C ratio. This abundance of oxygenated (acidic) functional groups facilitates the formation of complexes between soil PTEs and the oxygenated functional groups present both internally and externally on the biochar. Consequently, this leads to the effective immobilization of soil PTEs8,37,38. The formation of complexes can occur between positively charged metal cations and oxygenated functional groups, specifically the C = O groups. For example, a surface complex can be formed between Cd+ 2 and free carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups. The formation process of these complexes can be represented by the following equation39:

Bian, et al.40 applied an activated carbon for removal of Cd ions from aqueous solutions. They concluded that cation exchange between Cd and surface oxygen-containing functional groups of activated carbon and electrostatic attraction was the main mechanism of Cd immobilization. The greatest increase in the concentration of soil Cd bound to organic matter (Cd-OM) compared to the control was related to the application of SA by 20.5% (Table 3) which further confirms the proposed mechanism of Cd immobilization by organic complexation. Whereas the biochars derived from rice husk did not have a significant effect on soil Cd-OM content (Table 3). Similarly, Lu, et al.41 observed that the impact of biochars on the concentration of soil Cd-OM fraction varied depending on factors such as the type of biochar, mesh size, and application rate. Increasing the soil PTEs bound to organic matter as affected by the addition of biochars to soils has been previously documented42,43. The greatest contents of the Cd-WsEx and Cd-OM fractions were observed in the soils with sandy loam (L) and silty clay loam (H) textural classes, respectively (Table 3). The sandy loam soil had the lowest CEC and organic matter content among the three soil textural classes (Table 1), and thus had the lowest soil buffering capacity resulting in the highest Cd-WsEx and lowest Cd-OM concentrations (Table 3). The interaction effects of treatments also showed that the lowest concentration of Cd-WsEx was attributed to the combined treatment of RA + H (9.99 mg Cd kg−1 soil) (Table 3). In a study conducted by Bashir, et al.34, a rice straw-derived biochar was modified with KOH and applied to soil contaminated with Cd. In agreement with the present study, their FTIR and SEM analyses showed that the base-modified biochar exhibited increased CEC and microporous structures. Moreover, new surface functional groups, specifically -COOH, appeared on the modified biochar. The application of KOH-modified rice straw biochar resulted in a significant reduction in the content of Cd-WsEx (water-soluble and exchangeable Cd) in the soil. In another study, Rehman, et al.44 with the application of a modified rice husk biochar with three different acids (HCl, HNO3, and H3PO4) discovered that the acid-modified biochars showed a significant decrease in the soluble Cd content in a contaminated soil. Upon the application of the biochar treated with phosphoric, nitric, and hydrochloric acids, the soil-available concentrations of Cd were reduced by 86.6%, 76.6%, and 60.5%, respectively, compared to the control.

Addition of all the biochars except R and RB treatments led to a significant increase in the soil Cd content bound to FeMn-Oxides compared to the CL, with the SA treatment being the most effective increasing it by 21% (Table 3). In general, the modified and unmodified sheep manure biochars were more effective at enhancing the Cd-FeMnOx fraction concentration than the rice husk biochars (Table 3). In line with our findings, fractionation of Cd in calcareous soils has shown that a significant part of this metal is bound to iron and manganese oxides, especially for soils with higher clay content6,45. The variable surface charge, high specific surface area, and surface reactivity of Fe (hydr)oxides play a crucial role in their interaction with diverse components in the natural environment. These properties are essential for the processes of immobilization, transport, and bioavailability of soil PTEs46,47. In natural environments, it is uncommon for Fe (hydr)oxides and organic matter (OM) to exist independently as distinct components. Instead, they frequently interact with each other, leading to the formation of Fe-OM associations48,49. Organo-mineral composites are commonly formed through the strong binding ability between the oxygen-containing functional groups, primarily carboxyl groups (–COOH) and phenolic hydroxyl groups (-OH) found on OM and the hydroxyl groups (-OH) present on Fe (hydr)oxides49,50. Organo-mineral composites exhibit higher adsorption capacities for PTEs compared to their individual constituents. This is primarily due to the documented increase in specific surface area, negative charge, and available adsorption sites resulting from the adsorption/co-precipitation of certain OM molecules with Fe (hydr)oxides. As a result, these organo-mineral composites demonstrate enhanced adsorption capacities for PTEs when compared to their individual components51,52. The formation of Fe-oxides-OM composites leads to an increase in the negative charge associated with the surface of Fe-oxides. This change promotes the binding of cationic metals onto the surfaces of Fe-oxides53. In the present study, it appears that incorporation of SA with higher oxygen-containing functional groups promoted the formation of biochar-FeMn-oxides composites and resulted in greater Cd adsorption onto soil FeMn-oxides.

Among the biochars, SA and SB resulted in a significant increase in the soil Cd-Res content compared to the control (Table 3). Sheep manure biochars had considerably higher P content than the rice husk biochars (Table 2). Therefore, sheep manure biochars might be able to form insoluble compounds such as Cd-phosphate in soil. Moreover, biochars derived from oxidized sheep manure exhibited higher levels of oxygenated functional groups (Table 2; Fig. 1). These characteristics likely led to the formation of OM-P complexes, resulting in an increased presence of negative surface charges in soils. Consequently, this facilitates the enhanced retention of Cd through electrostatic attraction54. Zheng, et al.55 reported an increased soil Cd content in the Res fraction with addition of a chitosan-EDTA modified biochar at a rate of 2% (w/w) to a contaminated soil. They stated that increasing of soil organic matter due to biochar application had been responsible for Cd conversion to a highly stable state. In another study, Zhong, et al.56 concluded that application of KOH-modified cotton straw biochar was more effective than unmodified biochar for stabilizing soil Cd through conversion of Cd-WsEx form to FeMnOx, OM, and Res fractions. There was a significantly greater concentration of soil Cd within Res fraction in the silty clay loam soil with higher clay content (H) compared to the sandy loam soil (L) (Table 3). Rassaei57 compared two calcareous soils with distinct clay contents for their capacity to retain different Cd chemical fractions. In agreement with the present study, Rassaei57 indicated that the Cd Res concentration was higher in a clay soil (53% clay) than a sandy clay loam soil (23% clay). In another study, Maftoun, et al.58 concluded that clay and calcium carbonate contents are the major factors of Cd retention in calcareous soils of Iran.

Cd desorption as affected by biochars and soil textural classes

The influence of the modified and unmodified biochars on the cumulative Cd (mg kg− 1) desorption by EDTA from the Cd-polluted soils is shown in Fig. 3. The desorption of Cd from the biochar-treated soils appeared to occur in two-stages. Initially, Cd desorbed from the amended soils at a high rate, and then after 2 h, the rate of Cd release diminished until it reached equilibrium at 24 h (Fig. 3). This is supported by the fact that on average about 78% of total released Cd during 24 h was desorbed in the first two hours. The two-staged desorption of soil PTEs by chelating agents (DTPA and EDTA) in biochar-amended calcareous soils was also reported by other studies35,59. In the initial two hours, the release of Cd is likely occurring from sites with lower absorption energy, resulting in a high release rate (referred to as the first stage). Subsequently, Cd is gradually released from sites with higher absorption energy, leading to a lower release rate (referred to as the second stage). Typically, the Cd desorbed during the first phase comprises the WsEx fraction, which can be more easily extracted by EDTA. The second stage is attributed to Cd complexes that require more time to detach or Cd forms that are strongly attached to soil particles with high adsorption energies such as Cd associated with the Res and FeMnOx fractions35,60. The highest amount of EDTA-released Cd over 24 h was observed in the treatment without the use of biochar and sandy loam soil (CL + L) (47.15 mg Cd kg− 1 soil), attributed to its low buffering capacity (Table 1). Whereas, the lowest amount of released Cd (41.12 mg Cd kg− 1 soil) was observed in the silty clay loam textural class (H) amended with the NaOH-sheep manure biochar (SB + H). However, the lowest content of Cd-WsEx was observed in the SA + H combined treatment (Table 3). Although carboxyl peak intensity of SB was lower than that for the SA (Fig. 1), the application of SB increased the soil pH by 0.3 units compared to the control. Furthermore, SA contained a lower ash (Table 2) and calcium carbonate content (Fig. 1) than SB. Therefore, unlike SA, SB could likely immobilize soil Cd via two simultaneous mechanisms of complexation and precipitation (the formation of insoluble compounds such as Cd-hydroxides, Cd-carbonates and Cd-phosphates8). The desorption of Cd-complexes from carboxyl groups is easier than those from insoluble Cd compounds, thus explaining the lower cumulative Cd desorption from the SB + H treatment. Addition of Fe-modified rice husk biochar to a weakly alkaline soil led to a decrease in the DTPA–Cd content by 37.7–41.6% in contrast with control soil61.

Cumulative desorption of soil Cd (mg kg−1) by EDTA solution as affected by biochars and soil textural classes. Notes: Cl, control (with no biochar application); R, rice husk biochar; RA, rice husk biochar modified by HNO3; RB, rice husk biochar modified by NaOH; S, sheep manure biochar; SA, sheep manure biochar modified by HNO3; SB, sheep manure biochar modified by NaOH; H, silty clay loam; M, Loam; L, sandy loam.

Applying two-first order reaction model for Cd-release data

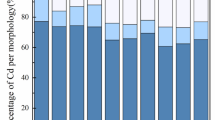

The EDTA Cd-release data was accurately described by the two-first order reaction kinetics model in agreement with previous studies on the release of Pb, Cd, and Cr from calcareous soils in southern Iran (Saffari, et al.62; Boostani, et al.22). The model’s performance was assessed using the standard error of estimate (SEE), which ranged between 0.43 and 2.09 with a mean of 1.02, and the coefficient of correlation (R2), which ranged between 0.88 and 0.99 with a mean of 0.97. The parameters of the two-first order reaction kinetics model (G1, G2, and G3) were determined and compared across different biochar and soil textural classes (Table 4; Fig. 4). The main effects of biochars, soil textural classes and their interactions on the G1 and G3 parameters were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.01), while the interaction effects of treatments on the G2 parameter were not significant. The G1 parameter represents the concentration of labile Cd, which corresponds to the easily extractable form. Whereas the G2 parameter represents the fraction of Cd that is less labile. Lastly, the G3 parameter indicates the presence of Cd in a non-extractable form30. All the biochar treatments significantly decreased the magnitude of G1 parameter compared to the control, with the maximum reduction observed in the SB treatment by 13.1% (Table 4). The sheep manure biochars significantly decreased the G1 parameter compared to the rice husk biochars (Table 4). Furthermore, the maximum values of G2 and G3 parameters were attributed to the SB treatment (Table 4; Fig. 4). These results also verified that the soils amended with SB treatment had the lowest Cd release by EDTA chelating agent compared to other biochar treatments. In a study, the addition of different biochars (maize straw, cotton residue and wheat straw) at a rate of 1.5% (w/w) to a Cd-contaminated calcareous soil reduced the G1 parameter, while the G3 parameter was increased compared to the control, significantly35. The G1, G2, and G3 parameters findings also showed that the greatest release of soil Cd by EDTA was observed in the sandy loam soil (L) with lowest content of clay and organic matter (Table 4).

Amount of soil Cd (mg kg−1) associated with the G2 parameter derived from two-first order kinetics equation as affected by biochars and soil textural classes. Notes: Cl, control (with no biochar application); R, rice husk biochar; RA, rice husk biochar modified by HNO3; RB, rice husk biochar modified by NaOH; S, sheep manure biochar; SA, sheep manure biochar modified by HNO3; SB, sheep manure biochar modified by NaOH; H, silty clay loam; M, Loam; L, sandy loam. Numbers followed by the same letters in each section are not significantly (P < 0.05) different.

Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was employed to determine the relationships between soil Cd chemical forms and the parameters derived from the two-first order reaction kinetics model (G1, G2, and G3) (Table 5). The most influential chemical fraction on the G1 parameter was Cd-OM (r=-0.31*). This significant negative correlation confirmed that Cd complexation by organic functional groups is one of the important mechanisms for reducing the soil Cd mobility in the present study. In contrast, the G3 parameter had a significant positive correlation with the Cd chemical fractions of FeMnOx (r = + 0.34**), OM (r = + 0.32**) and Res (r = + 0.40**) (Table 5). Furthermore, the G3 parameter and soil Cd in the WsEx fraction had a significant negative correlation (r = − 0.40**) (Table 5). This finding indicated that the conversion of soil bioavailable Cd (WsEx) into the fractions with higher stability including FeMnOx, OM and Res led to a reduction in Cd desorbing by EDTA from the contaminated calcareous soils.

Conclusions

The present study investigated the application of acid-base modified biochars derived from two different sources (rice husk and sheep manure) compared to the unmodified biochars for stabilizing soil Cd in three contaminated calcareous soils with different textural classes and the mechanisms governing it using FTIR, SEM, sequential extraction procedure and release kinetics study. Acid (HNO3)-modified sheep manure biochar was the best treatment for stabilizing soil Cd through conversion of Cd-WsEx form to FeMnOx, OM, and Res fractions. This was due to the increase in surface oxygen functional groups, especially carboxyl, on the acid-modified sheep manure biochar which could complex Cd. However, the HNO3-modified sheep manure biochar released more of the immobilized Cd by EDTA extraction than the NaOH-modified sheep manure biochar. It was found that the EDTA-release of R-O-Cd complexes was easier than Cd associated with insoluble compounds. This was likely due to the acidic pH and lower ash content of the acid-modified biochar compared to the base-modified biochar, which is not conducive to Cd precipitation reactions. Furthermore, Cd mobility was higher in the sandy loam soil with low clay content, thus it is critical to immobilize Cd in light-textured soils in order to prevent its transfer to the life cycle of plants and humans. Finally, it is suggested that the NaOH-sheep manure biochar could be used as a promising amendment for stabilizing Cd in contaminated calcareous soils with various textures and should be further tested under field conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current research are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Xiao, R., Wang, S., Li, R., Wang, J. J. & Zhang, Z. Soil heavy metal contamination and health risks associated with artisanal gold mining in Tongguan, Shaanxi, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 141, 17–24 (2017).

Christou, A., Theologides, C. P., Costa, C., Kalavrouziotis, I. K. & Varnavas, S. P. Assessment of toxic heavy metals concentrations in soils and wild and cultivated plant species in Limni abandoned copper mining site, Cyprus. J. Geochem. Explor. 178, 16–22 (2017).

Kubier, A., Wilkin, R. T. & Pichler, T. Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Appl. Geochem. 108, 104388 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Removal of cd and pb with biochar made from dairy manure at low temperature. J. Integr. Agric. 18, 201–210 (2019).

Li, Z., Ryan, J. A., Chen, J. L. & Al-Abed, S. R. Adsorption of cadmium on biosolids‐amended soils. J. Environ. Qual. 30, 903–911 (2001).

Boostani, H., Hardie, A., Najafi-Ghiri, M. & Khalili, D. Investigation of cadmium immobilization in a contaminated calcareous soil as influenced by biochars and natural zeolite application. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 15, 2433–2446 (2018).

Ahmad, M. et al. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 99, 19–33 (2014).

Bandara, T. et al. Chemical and biological immobilization mechanisms of potentially toxic elements in biochar-amended soils. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 903–978 (2020).

Boostani, H. R., Hardie, A. G., Najafi-Ghiri, M. & Zare, M. Chemical speciation and release kinetics of Ni in a Ni-contaminated calcareous soil as affected by organic waste biochars and soil moisture regime. Environ. Geochem. Health 45, 199–213 (2023).

Zhang, J., Liu, J. & Liu, R. Effects of pyrolysis temperature and heating time on biochar obtained from the pyrolysis of straw and lignosulfonate. Bioresour. Technol. 176, 288–291 (2015).

Li, H. et al. Mechanisms of metal sorption by biochars: Biochar characteristics and modifications. Chemosphere 178, 466–478 (2017).

Uchimiya, M., Bannon, D. I. & Wartelle, L. H. Retention of heavy metals by carboxyl functional groups of biochars in small arms range soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 1798–1809 (2012).

Zheng, X. et al. Nitric acid-modified hydrochar enhance Cd2 + sorption capacity and reduce the Cd2 + accumulation in rice. Chemosphere 284, 131261 (2021).

Boostani, H. R., Hardie, A. G. & Najafi-Ghiri, M. Effect of organic residues and their derived biochars on the zinc and copper chemical fractions and some chemical properties of a calcareous soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 51, 1725–1735 (2020).

Boostani, H. R., Hardie, A. G., Najafi-Ghiri, M. & Khalili, D. The effect of soil moisture regime and biochar application on lead (pb) stabilization in a contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111626 (2021).

Gee, G. W. & Bauder, J. W. Particle-size analysis. Methods Soil. Analy. Part. 1 Phys. Mineral. Methods 5, 383–411 (1986).

Rhoades, J. & Salinity Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. Methods Soil. Anal. Part. 3 Chem. Methods 5, 417–435 (1996).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods Soil. Anal. Part. 3 Chem. Methods 5, 961–1010 (1996).

Loeppert, R. H. & Suarez, D. L. Carbonate and gypsum. Methods Soil. Anal. Part. 3 Chem. Methods 5, 437–474 (1996).

Sumner, M. E. & Miller, W. P. Cation exchange capacity and exchange coefficients. Methods soil. Anal. Part 3 5, 1201–1229 (1996).

Lindsay, W. L. & Norvell, W. Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese, and copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 42, 421–428 (1978).

Boostani, H. R., Najafi-Ghiri, M., Hardie, A. G. & Khalili, D. Comparison of pb stabilization in a contaminated calcareous soil by application of vermicompost and sheep manure and their biochars produced at two temperatures. Appl. Geochem. 102, 121–128 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Effects of feedstock type, production method, and pyrolysis temperature on biochar and hydrochar properties. Chem. Eng. J. 240, 574–578 (2014).

Abdelhafez, A. A., Li, J. & Abbas, M. H. Feasibility of biochar manufactured from organic wastes on the stabilization of heavy metals in a metal smelter contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 117, 66–71 (2014).

Keiluweit, M., Nico, P. S., Johnson, M. G. & Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1247–1253 (2010).

Jin, J. et al. HNO3 modified biochars for uranium (VI) removal from aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 256, 247–253 (2018).

Salbu, B. & Krekling, T. Characterisation of radioactive particles in the environment. Analyst 123, 843–850 (1998).

Sposito, G., Lund, L. & Chang, A. Trace metal chemistry in arid-zone field soils amended with sewage sludge: I. Fractionation of Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd, and Pb in solid phases. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 46, 260–264 (1982).

Dang, Y., Dalal, R., Edwards, D. & Tiller, K. Kinetics of zinc desorption from Vertisols. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 58, 1392–1399 (1994).

Santos, S. et al. Influence of different organic amendments on the potential availability of metals from soil: A study on metal fractionation and extraction kinetics by EDTA. Chemosphere 78, 389–396 (2010).

Zemnukhova, L. A., Panasenko, A. E., Artem’yanov, A. P. & Tsoy, E. A. Dependence of porosity of amorphous silicon dioxide prepared from rice straw on plant variety. BioResources 10, 3713–3723 (2015).

Myszka, B. et al. Phase-specific bioactivity and altered Ostwald ripening pathways of calcium carbonate polymorphs in simulated body fluid. RSC Adv. 9, 18232–18244 (2019).

Peiris, C. et al. The influence of three acid modifications on the physicochemical characteristics of tea-waste biochar pyrolyzed at different temperatures: A comparative study. RSC Adv. 9, 17612–17622 (2019).

Bashir, S. et al. Efficiency of KOH-modified rice straw-derived biochar for reducing cadmium mobility, bioaccessibility and bioavailability risk index in red soil. Pedosphere. 30, 874–882 (2020).

Boostani, H. R., Hardie, A. G. & Najafi-Ghiri, M. Chemical fractions, mobility and release kinetics of Cadmium in a light-textured calcareous soil as affected by crop residue biochars and Cd-contamination levels. Chem. Ecol. 1–14 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. The long-term effectiveness of ferromanganese biochar in soil cd stabilization and reduction of cd bioaccumulation in rice. Biochar. 3, 499–509 (2021).

Inyang, M. I. et al. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 406–433 (2016).

Shakya, A. & Agarwal, T. Potential of biochar for the remediation of heavy metal contaminated soil. Biochar Appl. Agric. Environ. Manage. 77–98 (2020).

Wang, Y., Wang, H. S., Tang, C. S., Gu, K. & Shi, B. Remediation of heavy-metal-contaminated soils by biochar: A review. Environ. Geotechnics. 9, 135–148 (2019).

Bian, Y. et al. Adsorption of cadmium ions from aqueous solutions by activated carbon with oxygen-containing functional groups. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 23, 1705–1711 (2015).

Lu, K. et al. Effect of bamboo and rice straw biochars on the mobility and redistribution of heavy metals (cd, Cu, Pb and Zn) in contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manage. 186, 285–292 (2017).

Qin, P. et al. Bamboo-and pig-derived biochars reduce leaching losses of dibutyl phthalate, cadmium, and lead from co-contaminated soils. Chemosphere. 198, 450–459 (2018).

Xu, P. et al. The effect of biochar and crop straws on heavy metal bioavailability and plant accumulation in a cd and pb polluted soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 132, 94–100 (2016).

Rehman, M. Z. et al. Effect of acidified biochar on bioaccumulation of cadmium (cd) and rice growth in contaminated soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 19, 101015 (2020).

Rassaei, F., Hoodaji, M. & Abtahi, S. A. Cadmium chemical forms in two calcareous soils treated with different levels of incubation time and moisture regimes. J. Environ. Prot. 10, 500 (2019).

Amini, M., Antelo, J., Fiol, S. & Rahnemaie, R. Modeling the effects of humic acid and anoxic condition on phosphate adsorption onto goethite. Chemosphere 253, 126691 (2020).

Xie, X. & Cheng, H. Adsorption and desorption of phenylarsonic acid compounds on metal oxide and hydroxide, and clay minerals. Sci. Total Environ. 757, 143765 (2021).

Xue, Q., Ran, Y., Tan, Y., Peacock, C. L. & Du, H. Arsenite and arsenate binding to ferrihydrite organo-mineral coprecipitate: Implications for arsenic mobility and fate in natural environments. Chemosphere 224, 103–110 (2019).

Du, H., Peacock, C. L., Chen, W. & Huang, Q. Binding of cd by ferrihydrite organo-mineral composites: Implications for cd mobility and fate in natural and contaminated environments. Chemosphere 207, 404–412 (2018).

Kleber, M. et al. Mineral–organic associations: Formation, properties, and relevance in soil environments. Adv. Agron. 130, 1–140 (2015).

Liu, Q. et al. Characterization of goethite-fulvic acid composites and their impact on the immobility of Pb/Cd in soil. Chemosphere 222, 556–563 (2019).

Xiong, J. et al. Effect of soil fulvic and humic acids on pb binding to the goethite/solution interface: Ligand charge distribution modeling and speciation distribution of Pb. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 1348–1356 (2018).

Wei, S. & Xiang, W. Adsorption removal of pb (II) from aqueous solution by fulvic acid-coated ferrihydrite. J. Food Agric. Environ. 11, 1376–1380 (2013).

Wu, X. et al. Insight into the mechanism of phosphate and cadmium co-transport in natural soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 435, 129095 (2022).

Zheng, L. et al. Effects of Modified Biochar on the mobility and speciation distribution of Cadmium in Contaminated Soil. Processes 10, 818 (2022).

Zhong, M. et al. Improving the ability of straw biochar to remediate cd contaminated soil: KOH enhanced the modification of K3PO4 and urea on biochar. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 262, 115317 (2023).

Rassaei, F. Effect of monocalcium phosphate on the concentration of cadmium chemical fractions in two calcareous soils in Iran. Soil. Sci. Annu. 73 (2022).

Maftoun, M., Rassooli, F., Ali Nejad, Z. & Karimian, N. Cadmium sorption behavior in some highly calcareous soils of Iran. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 35, 1271–1282 (2004).

Raeisi, S., Motaghian, H. & Hosseinpur, A. R. Effect of the soil biochar aging on the sorption and desorption of pb 2 + under competition of zn 2 + in a sandy calcareous soil. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–12 (2020).

Kandpal, G., Srivastava, P. & Ram, B. Kinetics of desorption of heavy metals from polluted soils: Influence of soil type and metal source. Water Air Soil Pollut. 161, 353–363 (2005).

Sun, T. et al. Cd immobilization and soil quality under Fe–modified biochar in weakly alkaline soil. Chemosphere 280, 130606 (2021).

Saffari, M., Karimian, N., Ronaghi, A., Yasrebi, J. & Ghasemi-Faseai, R. Reduction of chromium toxicity by applying various soil amendments in artificially contaminated soil. J. Adv. Environ. Health Res. 2, 251–262 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by College of Agriculture and Natural Resources of Darab, Shiraz University, Darab, Iran and Soil and Water Research Department, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Shiraz, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.R.B. Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Validation and S.M.H. Review & Editing, Project administration, Visualization and A.G.H. Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boostani, H.R., Hosseini, S.M. & Hardie, A.G. Mechanisms of Cd immobilization in contaminated calcareous soils with different textural classes treated by acid- and base-modified biochars. Sci Rep 14, 24614 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76229-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76229-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Tackling New-generation Pollutants in Soil: How Modified Biochar Redefines Remediation Strategies?

Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology (2026)

-

Comparative effectiveness of pristine and H3PO4-modified biochar in combination with bentonite to immobilize cadmium in a calcareous soil

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Impact of land-use conversion from a long-term paddy to abandoned field on the distribution of C, N, and trace elements: a study in central Viet Nam

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2025)