Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the adaptation and effectiveness of telemedicine with the diffuse-dual-channel system (DDS) and tiered-gatekeeper system (TGS) across different tiers of the healthcare system on technical-organizational-environmental (TOE) framework. The telemedicine services were extended as Tiered-gatekeeper system (TGS) by Primary and Secondary Healthcare (PSHC) and Diffuse-dual-channel system (DDS) by King Edward Medical University (KEMU) in 2020 benefiting 2605 and 21,905 patients, respectively. This cross-sectional survey is based on a structured questionnaire conducted on 172 healthcare practitioners (HCP) from KEMU and 76 from PSHC selected by purposive sampling and analysis is conducted through descriptive analysis and the Boruta features selection method. The diffuse-dual-channel system is found to be flexible, easy to implement, and impactful due to innate compatibility with prevailing healthcare practices, however, it is a parallel effort to the existing healthcare system. The tiered-gatekeeping system is found to be complex in adaptation initially, but is more organized, deeply integrated, accountable and channelizes the flow of patients, resultantly aiding the preservation of resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, telemedicine has revolutionized technology in the field of medical sciences and improved primary healthcare services particularly in the wake of the pandemic1,2,3. Telemedicine services not only offer convenience to patients by allowing them to get easy access to medical services in the community healthcare center or at their homes but also links medical professionals across great distances, which can be helpful to both patients and physicians4. Inequitable resource distribution between rural and urban populations results in subpar medical care and reduced service delivery efficiency at certain tiers, which can be attuned by sharing existing medical resources5. Telemedicine can improve health systems by making care more accessible, cheaper, safe, and standardized. Nonetheless, there are other obstacles that telehealth must overcome, including the issues of limited in-person human interaction, data security, confidentiality, accessibility, and training. Despite of necessary prerequisites requirement, telemedicine holds great promise for enhancing and bolstering medical care and may reduce congestion in hospitals6,7.

TOE framework is based on the diffusion of innovation theory explaining the processes and key factors involved in the spread of new technologies, affecting innovation adoption at the organizational level8,9. It is a valuable tool for understanding the dense interplay between technology, organization, and environmental aspects. Olivera summarized applications of the TOE Framework10. Awa also reiterated that organizational level analysis can be conducted with the TOE framework11. Limited modification has been made in this framework since its introduction, and is comparatively more generic, and less competitive with higher degree of freedom to alter factors8,12,13. The strengths of TOE framework are its flexibility and capacity to provide holistic perspective on technology adoption. Skurdi utilized Moderated Regression Analysis (MRA) for quantitative analysis of TOE model14.

In various healthcare contexts, telemedicine is implemented through either a gatekeeper system or a dual-channel system7. The dual channel system involves both online and offline services without any condition of triage7. The gatekeeper system involves triage, where regulations in the gatekeeper system are designed to force patients to receive their initial diagnosis at the telemedicine center; in this case, patient choice has no bearing on the telemedicine service capacity decision. The gatekeeper system may cost less and can be the ideal approach in limited circumstances, however, a dual channel system is the most preferable option as it is a blend of the traditional outpatient system and the gatekeeper system7. Large hospitals are more likely to view telemedicine as a means of delivering expert medical care to patients, but smaller institutions are better equipped to use it as a gatekeeper to assist in patient triage15. The classical healthcare systems are either diffuse in which patients can directly opt for a specialist without any triage; or tiered, where specialist consultation requires referral from the initial visit to the general practitioner. Good health services are always those that prove to be effective, safe, and steered with minimum waste of resources. In Pakistan, although the healthcare system is divided into three tiers primary, secondary and tertiary, but the prevailing practice is diffused.

There are no prevailing laws and regulations related to telemedicine at the federal level. At the provincial level, only the government of Sindh has approved Telemedicine and Telehealth Act 2021. However, few telemedicine services related guidelines are provided by the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC). Pakistan’s reliance on telemedicine increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and various emergency response telemedicine services were launched like “Sehat Kahani”, IPAS “Intelligent Project Automation System (IPAS) Pakistan”, “Oladoc”, “Marham”, “Ring a doctor,” and “eDoctor”16. During the pandemic, a blend of services was introduced to facilitate masses and reduce the burden on healthcare facilities. The tiered system was merged with gatekeeper where regulations were designed to get patients to receive their initial diagnosis at the level of the general practitioner at the telemedicine hub; and if needed, specialty consultation is taken onboard through telemedicine or in person referral. The dual-channel system was merged with the diffuse system where the boundaries between the general practitioner and specialist were blurred, and patients can directly approach any specialist, bypassing general practitioner.

The focus of this study is to compare telemedicine implementation, acceptability, and effectiveness in different tiers of the healthcare system through both diffuse-dual-channel system (DDS) and tiered-gatekeeper system (TGS) with the aim to identify which system can be better compatible with the existing healthcare system. Both healthcare systems are prevalent in Pakistan with different implications in relevance to telemedicine engagement, requirement of resources, patient accessibility, network bandwidth, geographical distribution, centralized reporting, HCPs availability and system’s capacity. The traceability of the burden of diseases is efficient in TGS. The study aims to investigate key variables for safe and continuous effective delivery of healthcare services by empowering masses for convenient addressal of healthcare at the doorstep through telemedicine. In addition, it provides a guideline for policy making agencies to strengthen the mixed model constituting offline and online healthcare services, mitigating the challenges of higher burden of diseases in health facilities in developing countries.

Methods

Study design

This analytical comparative cross-sectional study is based on a survey of healthcare practitioners (HCP) to compare and identify variables affecting telemedicine adaptability and effectiveness with DDS and TGS in different tiers of the healthcare system.

Setting

The PSHC in Punjab comprises of basic health units (BHU), tehsil and district headquarter hospitals (THQH and DHQH), while tertiary healthcare (THC) includes teaching hospitals and affiliated medical universities. For research purposes, the Lahore Division was selected during the pandemic in March 2020, as it was declared an epicenter for COVID-19 and telemedicine clinics were established at both tiers in Lahore. The telemedicine services adopted at PSHC consisted of the Hub and Spoke model with TGS. The BHU provided general practitioner services 24/7; however, Spoke was installed at BHUs, and specialty services were provided by telemedicine centers established at THQH and DHQH. The DDS telemedicine services were given by KEMU at THC. The data collected from the THC is from March 2020 to three years onward and from PSHC from August 2020 to four months onward.

Participants

A total of 1797 medical professionals at the PSHC and THC were registered. A total of 2605 and 21,905 patients received telemedicine consultation services from 155 practitioners at the PSHC and 1118 practitioners at the THC, respectively. The survey targeted covid 19 advisors, general practitioners, and specialists in various specialties from both tiers who performed an acceptable number of telemedicine consultations as per eligibility criteria (greater than 9 telemedicine consultations) from the telemedicine portals authorized by the Government of Punjab.

Variables

A total of twenty-four variables were studied under the subdomains of the TOE model which are technical facilitation (TF), organizational acceptance (OA), environmental behavior (EB) and moderator factors (MF). The EB includes all those variables which portray the impact of services. The dependent variables, compatibility with the healthcare system V5, integration with healthcare system V18 and requirement in pandemic V16 were assessed to find out important variables for the execution of telemedicine with reference to both TGS and DDS in our existing healthcare system. The TOE domains and associated variables are shown in Fig. 1.

Data collection instrument and collection procedure

The questionnaire used in this study was adopted from the telehealth utility questionnaire (TUQ)17,18,19 to comply study aims, the domain of TOE framework20,21, literature review22,23,24,25,26,27, and existing culture in the healthcare system of Pakistan28. The questions and variables were thematically arranged to conform to the requirements of various domains of the TOE framework including organizational acceptance, environmental behavior, technical facilitation, and moderator factors while ensuring the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. The Cronbach Alpha reliability test and Pearson correlation validity test of the questionnaire (supplementary file 2) exhibited high reliability (0.87) and valid (P < 0.05), respectively.

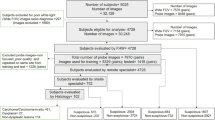

The HCPs completed an online survey with embedded written consent. In accordance with our inclusion and exclusion criteria, 401 qualified healthcare practitioners from both tiers (THC n = 308, PSHC n = 93) were given access to the online questionnaire; 248 (THC n = 172, PSHC n = 76) surveys submitted in time, were included in the study.

Study size and sampling technique

Purposive sampling was conducted to ensure the involvement from both systems (TGS and DDS), participation from majority of specialties, and HCPs with an adequate quantity of performances in the telemedicine field. Cochran’s sample size formula29 for a finite population is used for conducting the survey effectively, as given by:

Where, SS is the sample size, z is the z-score, p is the population proportion (standard deviation), ε is the margin of error and N is the total number of cases.

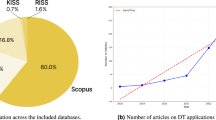

The sample sizes at 95% of confidence of interval (margin of error 5%) were calculated for both tiers; 172 from THC and 76 from PSHC. As per eligibility criteria 308 HCPs from THC and 93 from PSHC were outreached, 172 HCPs from THC and 76 HCPs from PSHC voluntarily took part and promptly answered the survey (Fig. 2).

Statistical methods

The data was compiled and analysed with descriptive analysis. For the Cronbach Alpha reliability test and Pearson correlation, SPSS software was used. Boruta feature selection method in R software was also used to figure out the feature selection for important variables in the TOE model for telemedicine8. To interpret results correctly, relevant features selection and reduction of noise (unrelated variables) are crucial steps. The irrelevant or unnecessary features are required to be suppressed or removed from the dataset for effective analysis. Some of the prominent algorithms for the dimensionality reduction include T-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), Boruta, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The Boruta algorithm is probably the easiest to interpret and implement. The questionnaire comprises of multiple variables, however, their significance and relevance to the outcome (patient satisfaction) is required to be determined and established. Boruta employs an iteratively statistical test-based process for the reduction of less relevant features and noise with possible random probes. In addition, the dataset can be reduced for effective analysis by reducing complexity and removing variables with minimum or no impact on the output. Boruta approach attempts to extract all the significant, intriguing features in the dataset regarding an outcome variable and based on the random forest classification technique. Boruta employs shadow features, which are duplicates of the original features with values that are randomly mixed, to eliminate their importance while maintaining the same distribution of the features. The significance of the shadow feature is computed and compared to the original features to declare rejected, tentative and confirmed features from the collection30.

Ethics approval

The approval was taken from PSHC department of Punjab, Pakistan (1587); Institutional Review Board of KEMU (164/REG/KEMU), and University of Punjab in Pakistan’s Ethical Review and Advanced Study Research Board (ref-9/2352- ACAD), and Ethical Institutional Review Board (EIRB) at Information Technology University of the Punjab (Ref: ITU/EIRB/2020/02) for the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Results

The demographic analysis of study participants is represented in Table 1. An online survey comprising of twenty-four questions based on the research objectives was conducted. The analysis of the HCP responses based on the Likert scale is shown in Fig. 3a,b.

Technical facilitation (digital connectivity and user-friendliness) is found to be a key area for improvement as about 50% of the HCPs were not satisfied with the technical facilities. Organizational acceptance (capacity building and medical education) needs significant improvements as well. The standardization of services and emphasis on patients’ safety was strongly supported by HCPs. The low feedback score of moderator factors (communication barrier) highlights a strong need for considering age-group based customization of telemedicine services and better connectivity. The DDS mode of telemedicine services, as compared to TGS were found to be more compatible with existing health systems.

Technical facilitation (TF)

The satisfactory responses about digital connectivity and user-friendliness were found to be 45.97% (58.14% THC, 18.42% PSHC) and 51.61% HCPs (57.56% THC, 38.16% PSHC), respectively. Telemedicine was recommended round the clock by 23.79% (26.16% THC, 18.42% PSHC), in morning and evening 21.77% (24.42% THC, 15.79% PSHC), morning shift only 41.53% (37.79% THC, 50% PSHC), evening shift only 10.08% (8.72% THC, 13.16% PSHC).

Organizational acceptability (OA)

The prerequisites for capacity building and medical education programs were acknowledged by 64.92% HCPs (70.93% THC, 51.32% PSHC) and 60.89% (81.40% THC, 14.47% PSHC) respectively. Obligation of telemedicine in pandemics was strongly agreed by 33.06% (43.60% THC, 9.21% PSHC) and agreed by 66.94% (56.40% THC, 90.79% PSHC) HCPs. Standardization of services was recommended by 82.66% (93.02% THC, 59.21% PSHC) HCPs. About 62.69% (65.98% THC, 55.26% PSHC) HCPs appreciated compatibility of telemedicine with the existing healthcare system and 83.47% (85.47% KEMU, 78.95% PSHC) HCPs proposed the necessity of telemedicine as an integral component in healthcare facilities. About 77.02% (84.88% THC, 59.21% PSHC) and 70.36% (80.23% THC, 48.02% PSHC) HCPs acknowledged patient safety and patient privacy, respectively. The HCPs perceived patient comfort and satisfaction were found to be 73.99% (73.26% THC, 75.66% PSHC) and 53.02% (56.68% THC, 44.73% PSHC).

Moderator factors (MF)

About 50% HCPs (47.67% THC, 55.26% PSHC) reported doctor-patient communication barrier. Perception of healthcare providers about patient gender-based communication convenience was found to be 51.21% for both males and females (63.37% THC, 23.68% PSHC), 27.02% for males only (19.19% THC, 44.74% PSHC) and 21.77% for females only (17.44% KEMU, 31.58% PSHC) whereas perception of healthcare providers about patient age-group based communication convenience was found to be 4.84% for 10–19 years (1.16% THC, 13.16% PSHC), 62.10% for 20–34 years (67.44% THC, 50% PSHC), 27.02% for 30–49 years (25% THC, 31.58% PSHC) and 6.05% for 50 years and above (6.40% KEMU, 5.26% PSHC).

Environmental behavior (EB)

About 62.09% (80.23% THC, 48.02% PSHC) HCPs were satisfied with telemedicine services; 83.47% (84.88% THC, 80.26% PSHC) HCPs acknowledged reduced physical visits of patients and 76.61% HCPs strongly agreed (90.12% THC, 46.05% PSHC) with the idea that telemedicine can help in resources preservation. When HCPs were asked to prioritize the most impactful outcome of telemedicine, about 44.35% (51.16% THC, 28.95% PSHC) were of the view that telemedicine can reduce the burden of the outpatient department, 20.97% (24.42% THC, 13.16% PSHC) were of the opinion that telemedicine can help in early diagnosis and treatment, 16.13% (16.86% THC, 14.47% PSHC) opted that telemedicine can reduce the financial cost at patient end, 18.15% (6.98% THC, 43.42% PSHC) stated that telemedicine can reduce the referrals from the rural areas.

This study investigates the practice of telemedicine and the effectiveness of the TGS and DDS models in the existing healthcare systems from HCP perspective. The Boruta feature selection method was conducted for both DDS in THC and TGS in PSHC on the TOE framework. In DDS (Fig. 4a–c), the EB (HCP satisfaction V14, resource preservation V15, impact V11, patient satisfaction V12, reduces visits V17), OA (patient privacy V8, quality standards V9, requirement in pandemics V16, patient safety V10, capacity building V20, compatibility with healthcare system V5) and MF (HCP specialty V4, HCP age V2, gender-based patient convenience) were found to have confirmed importance whereas the TF (recommended duration V19, user-friendliness V7), MF (age-based patient convenience V22) and OA (capacity building V20) were found to be tentatively important with respect to integral part in healthcare facilities V18.

The EB (HCP satisfaction V14, patient satisfaction V12, resource preservation V15, patient comfort V13, impact V11), TF (digital connectivity V6, user-friendliness V7, recommended duration V19), MF (gender-based patient convenience V24), OA (patient safety V10, quality standards V9, patient privacy V8, capacity building V20, requirement in pandemics V16, an integral part of health facilities V18) have confirmed importance and EB reduced visits V17 has tentative importance with reference to compatibility with healthcare system V5. The EB (resource preservation V15, patient satisfaction V12, reduced visits V17, HCP satisfaction V14, impact V11), OA (quality standards V9, integral part of health facilities V18, patient privacy V8, patient safety V10, compatibility with HCS V5) and MF (HCP specialty V4, HCP age V2, gender-based patient convenience V24) were confirmed as important variables whereas EB (Patient comfort V13), OA (capacity building V20) and TF (recommended duration V19, user-friendliness V7) were found to be tentatively important with respect to requirement in pandemics V16.

The THC Boruta analysis is shown in Fig. 4a–c and PSHC Boruta analysis is included in supplementary file Fig. 4d–f. In TGS (Fig. 4d–f), the variables of EB (patient satisfaction V12, resource preservation V15, reduces visits V17) were found to have confirmed importance with respect to compatibility with healthcare system V5. The OA (capacity building V20) and TF (user-friendliness V7) were found to have confirmed the importance for the requirement in pandemics V16. The variables OA (patient privacy V8), TF (recommended duration V19) and MF (age-based patient convenience V23) have confirmed their importance with as an integral part of health facilities V18.

Table 2 is summary of Boruta analysis on TOE framework for DDS and TGS. Figure 5 is graphical representation of confirmed and tentative important features for both systems.

Discussion

For continuous delivery of telemedicine services in DDS, younger and more innovative HCPs can perform well who are more familiar with the latest technologies31,32. The HCP age and specialty differentiation was not found to be an important variable in TGS as these requirements are already embedded in this model, as younger doctors are available at the initial encounter and relatively older specialists received referrals. The patients’ demographics were found to be important in DDS as relies on communication skills, necessary regulations, and patient privacy concerns34. A higher percentage of both genders of patients (63.37%) were seen as convenient in DDS, however, in TGS, males were found to be more convenient (44.74%) by HCPs. The 20–34 years patient age group was perceived to be most convenient in both systems by HCPs. The malleability trend declines with advancing age due to a lack of computer knowledge and incapability towards technological adaptability33. A small proportion of perceived satisfaction was also found in the geriatric population, due to help at basic health units by doctors in TGS for specialty consultations or at home by relatives34,35,36. The communication barrier was reported higher in TGS (55.26%) as compared to DDS (47.67%). Communication barrier exhibited lower importance in DDS which infers to the issues of patient perplexity, discomfort, physician dominance during teleconsultations and lack in technology proficiency. The loss of contact with patients can be resolved by extending empathy towards patients and developing communication skills in tele-consultations35,37,38,39,40,41. If concerns about inadequate patient care and technological difficulties are addressed adequately, communication barriers can be lowered and may result in promotion of telemedicine in the future42,43.

Higher satisfaction for digital connectivity was reported in DDS as compared to TGS. The limited, expensive, or lower quality bandwidth internet availability in rural areas may affect telemedicine usage. The user-friendliness is also observed more in DDS as it had a simpler interface as compared to TGS requiring assistance from Spoke for specialist consultation. The specified duration for telemedicine services was also found to be an important feature in DDS where services were being served only in the morning time; about 26% of HCPs proposed telemedicine services around the clock. Complex technology, long waiting times for patients and reluctance towards newer technology reduce the acceptability of telemedicine31,44. Access to broadband devices, continuous uninterrupted connectivity, digital competency, and capacity building has a crucial impact in eliminating digital disparity and about 71% increase in the desire to use telemedicine services was reported31,45.

In DDS, all variables of organizational acceptance were found to be significant which infers that patient privacy, comfort, HCP training, regulations and technology consultations between information technology experts and practitioners are important26,27. In TGS, capacity building and patient privacy were found significant. The patient safety in DDS was found to be much higher (84.88%) as compared to TGS (59.21%). Integration of telemedicine with the current health system and electronic health records may reduce medical errors and support clinical decision-making in telemedicine46. In other studies, practitioners opined that the quality of treatment provided in telemedicine was like in-person care25,27. Patient privacy was also found higher in DDS (80.23%) as compared to TGS (48.02%). During earlier stages of implementation, technology safety is not a priority, but it becomes compulsory in advanced stages47. The requirement for capacity building of HCPs was found to be 70% in DDS and 51% in TGS. The standardization of services was recommended by 93% and 59% HCPs in DDS and TGS respectively as TGS has already embedded regulations for systematic patient flow and referral. Organizational inputs and familiarity with technology are necessary elements for the smooth and seamless influx of telemedicine in existing healthcare systems. In addition, excellent communication, training, education, exposure to modern technologies, positive attitude of practitioners, and apparent effortlessness can enable an organization to offer telemedicine services effectively47,48.

The TGS implemented at PSHC showed maximum responses of HCPs (43.42%) in favor of a reduction of referrals from the rural areas. In another study at China, 92.5% of health care professionals believed that telemedicine aids in reduction of referrals with 95% HCPs willing to continue the practice of teleconsultations44. HCPs comparatively acknowledged a higher trend towards reduction of burden in outpatient departments (51.16%) and resource preservation (90.12%) in DDS. More than half of the outdoor patients currently treated in general hospitals can be well treated with telemedicine services49,50,51 and may bring a reduction in the requirement of human resources, routine outpatient clinics, infrastructure, and medical equipment costs15. Approximately 80% of responses in both models acknowledged reduced physical visits of patients. Reduced patient visits were also reported in a pilot study in United Kingdom, with 87.55% patient satisfaction and 85.71% HCP satisfaction52. The demands of patient care regarding chronic illnesses, postoperative care, nosocomial infections, and geriatric issues can be met by telemedicine services7,40. Research emphasized that satisfaction of HCPs and patients for adoption of telemedicine services is necessary34,53,54. About 80.23% HCPs of DDS and 48.02% HCPs of TGS were reported as satisfied with telemedicine services in numerous studies27,55. HCP satisfaction is directly proportional to their effective involvement during software designing phase19,56. Telehealth has potential to improve health care services by increasing the access, quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness52.

Both TGS and DDS have their own merits. It has been established that DDS is a better choice at the initial stages of implementation as it offers greater flexibility, however, TGS is preferable at later stages as it is more centralized and systematic7. A study conducted in Kenya revealed that 73% of doctors prefer a diffuse system as it ensures continuity of clinical services39. For pandemics, only user-friendliness and capacity building are appreciated in TGS. On the contrary, DDS has no control of HCPs over the distribution of patients and is patient-desire driven therefore technical, moderator and organizational components of TOE must be checked to address all expected implications. The doctors’ willingness to use telemedicine during pandemics may be influenced by movement restrictions57, however, guidelines are needed to address the concerns about communication gap and incomplete assessments of patients22. In this research, it is deduced that DDS produces maximum environmental impact due to close resemblance with existing diffuse healthcare systems as compared to TGS; DDS being a flexible model requires minimum integration efforts with existing healthcare systems. However, technical, and organizational variables must be attended continuously in DDS whereas TGS is systematically better regularized and organized, however, patient related concerns of privacy and convenience require addressal. The technical parameters in DDS were found to be tentatively important due to better bandwidth and comparatively easy access to telemedicine as THC offered multi-channel communication accessibility to patients. The moderator factors also got importance in DDS due to the direct access of patients to specialists without filtering through general practitioners. The TGS carries obstacles in remote areas due to its unfettered use, however, other valued services may bring a positive difference. The DDS not only minimizes the chances of mistreatment but also reduces the costs of telemedicine integration, which can further be reduced by bringing required adaptations in telemedicine and in-person consultations channelization7. A two-year survey in primary care revealed that while telemedicine adoption was initially challenging during the epidemic due to insufficient policy measures and infrastructure, by the end of the study period, practitioners considered telemedicine as both easier to use and essential for the success of their practice58.

Limitation of our study is the under representation of few specialties in either of the systems due to varying scope of different tiers which is overcome by considering proportionate inclusion of responses from HCPs of both tiers, irrespective of their assignment to any specialty. The possible sources of data biasing are addressed by a significant sample size, ensuring no missing data from both tiers as eliminated in the eligibility criteria and considering HCPs with a substantial number of patients served via telemedicine service. The potential confounding factors that may improve the telemedicine effectiveness are the inclusion of data related to comorbidity, median income, ethnicity, supporting medical insurance, number of prior successful telemedicine consultations, the device and network used for consultation. The ethical, economical, socio-cultural, minimum technological, evidence related, regulatory and licensing barriers should be addressed to improve telemedicine effectiveness. The limitations of data privacy and confidentiality can be improved by the incorporation of data encryption and essential cyber security measures. Another interesting approach with its associated limitations could be the adaptation of asynchronous methods to mitigate the challenges of communication skills, scarcity of health consultants and network bandwidth. The eligibility criteria have minimized any potential biases by focusing on evidence based immediate experiences of real-time performers.

The policymakers are recommended to devise and formulate minimum service delivery standards for the telemedicine consultation that are compatible with the current eco-system and implementable via relevant regulatory bodies. The related licensing framework and distributed models for intra-state connectivity, data sharing, privacy and security are critical. Moreover, a national electronic health record (EHR) system is required for the interpretability of patients’ records and history among various telemedicine platforms and other health information systems. The challenges and outcomes of telemedicine services implementation via diffuse-dual-channel system (DDS) and tiered-gatekeeper system (TGS) and related benefits are thoroughly investigated.

A comparative analysis of HCPs' feedback about in-person patient visits and telemedicine services may result in better assessment at both tiers. Future studies for assessing the clinical effectiveness of telemedicine services in both TGS and DDS healthcare systems are recommended. Additionally, research for the provision of an effective path for a smooth transition of telemedicine services from DDS to TGS is required. An in-depth research gap in determining the quality of care and long-term clinical effectiveness via telemedicine is identified. A comparative feedback comparison of both patient and HCP via telemedicine can be helpful for the complete detailed analysis of the effectiveness of the disease treatment. Keeping in view the limited resources, optimization techniques and algorithms should be employed to maximize HCP availability among patients. The impact on cost-effectiveness needs to be investigated in more detail. An adaptive roadmap to tailor telemedicine platforms is required to minimize the digital divide, socio-economic factors and health disparities among different populations, including rural and underprivileged groups. The mechanism to deal with chronic disease and its management with indicative predictive follow-up is required to be investigated. The challenges of certain specialized diseases’ management such as oncology and mental health via telemedicine also needed to be explored. Capacity building, continuous practice of telemedicine services, favorable infrastructure and network availability are key requirements for the successful implementation of telemedicine in any healthcare system59. Prompt response through telemedicine can help in improving patient-physician communication by addressing patients’ doubts and queries60. Even while enforcing digital health standards and policies at first may be difficult, doing so is necessary to preserve the community’s physical health in situations like COVID-19 and other unforeseen future events.

Conclusion

The study is comprehensive as it provides deep insight into factors affecting the adaptability of telemedicine in various tiers of the healthcare system. The study includes sample presentations of trained HCPs working in teleclinics of multiple specialties from all tiers of the healthcare system performing in both models of TGS and DDC. Telemedicine is compatible with existing healthcare system and can perform well in regular care and pandemics provided deployed technology is user-friendly; access to digital connectivity is enhanced; ethical concerns are addressed; and quality standards for delivery of telemedicine services are implemented. Telemedicine can play a key role in early diagnosis, effective treatment, symptomatic reliefs and provision of regular check-ups in case of antenatal care and chronic illnesses. The DDS is acceptable and impactful as compared to TGS in the initial phases as it has more similarity to the existing pattern of offline healthcare services. However, it requires continuous efforts and inputs in all domains of the TOE framework to remain effective. The TGS promotes the channelization of services at the initial stages and effectively helps in achieving the impact of telemedicine in a more accountable and organized manner with the passage of time. The compatibility of telemedicine with prevalent healthcare systems, government support, technological knowledge and team skills can have a positive effect on the intention to adopt telecare. At the micro level, technical, organizational, and ethical factors affect the implementation of telemedicine, while at the macro level financial, political, legal, socioeconomic, and cultural factors greatly affect adaptability; the interplay between identified factors can greatly assist the health authorities to develop effective and integrate-able telemedicine services.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Mann, D. M. et al. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 27, 1132–1135. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa072 (2020).

Ting, D. S. W. et al. Digital technology and COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 459–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0824-5 (2020).

Pappot, N., Taarnhoj, G. A. & Pappot, H. Telemedicine and e-health solutions for COVID-19: patients’ perspective. Telemed e-Health 26, 847–849. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0099 (2020).

Kumar, G. et al. Assessment of knowledge and attitude of healthcare professionals regarding the use of telemedicine: a cross-sectional study from rural areas of Sindh, Pakistan. Front. Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.967440 (2022).

Su, Z. et al. Review of the development and prospect of telemedicine. Intell. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imed.2022.10.004 (2022).

Bouabida, K., Lebouché, B. & Pomey, M. P. Telehealth and COVID-19 pandemic: An overview of the telehealth use, advantages, challenges, and opportunities during COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare (Switzerland) 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112293 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Impact of telemedicine on healthcare service system considering patients’ choice. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2019, 7642176. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7642176 (2019).

Baker, J. The Technology–organization–environment framework. In: Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society, Vol. 1 (eds. Dwivedi Yogesh K. et al.) 231–245 (Springer, 2012).

Baker, J. The technology–organization–environment framework. Inf. Syst. Theory, 231–245 (2011).

Oliveira, T. & Martins, M. R. Literature review of information technology adoption models at firm level. 1566–6379 14 (2011).

Awa, H. O., Ojiabo, O. & Orokor, L. Integrated technology-organization-environment (T-O-E) taxonomies for technology adoption. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 30, 0. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-03-2016-0079 (2017).

Dwivedi, Y., Wade, M. & Schneberger, S. Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society, Vol. 2 (2012).

Zhu, K. & Kraemer, K. L. Post-adoption variations in usage and value of e-business by organizations: cross-country evidence from the retail industry. Inf. Syst. Res. 16, 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1050.0045 (2005).

Sukardi, Hasyim, Supriyantoro. Using the technology-organization-environment framework approach in the acceptance of telemedicine in the health care industry. Eur. J. Bus. Manag Res. 6, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2021.6.3.837 (2021).

Wang, J-J., Zhang, X. & Shi, J. J. Hospital dual-channel adoption decisions with telemedicine referral and misdiagnosis. Omega (Westport). 119, 102875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2023.102875 (2023).

Ahmed, A. et al. Use of telemedicine in healthcare during COVID-19 in Pakistan: lessons, legislation challenges and future perspective. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 50, 485–486. https://doi.org/10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2020562 (2021).

Hajesmaeel-Gohari, S. & Bahaadinbeigy, K. The most used questionnaires for evaluating telemedicine services. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 21, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01407-y (2021).

Parmanto, B. et al. Development of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ). Int. J. Telerehabil. 8, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2016.6196 (2016).

Huang, J-C. Innovative health care delivery system—A questionnaire survey to evaluate the influence of behavioral factors on individuals’ acceptance of telecare. Comput. Biol. Med. 43, 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2012.12.011 (2013).

Chowdhury, A. et al. Conceptual framework for telehealth adoption in Indian healthcare.

Abd Ghani, M. K. & Jaber, M. M. Willingness to adopt telemedicine in major Iraqi hospitals: A pilot study. Int. J. Telemed Appl. 2015, 136591. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/136591 (2015).

Park, H-Y. et al. Satisfaction survey of patients and medical staff for telephone-based telemedicine during hospital closing due to COVID-19 transmission. Telemed e-Health 27, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0369 (2021).

Kasim, H. F., Salih, A. I. & Attash, F. M. Usability of telehealth among healthcare providers during COVID-19 pandemic in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq. Publ. Health Pract. 5, 100368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2023.100368 (2023).

Indria, D., Alajlani, M. & Fraser, H. S. F. Clinicians perceptions of a telemedicine system: a mixed method study of Makassar City, Indonesia. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 20, 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01234-7 (2020).

Idriss, S. et al. Physicians’ perceptions of telemedicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form. Res. 6, e36029. https://doi.org/10.2196/36029 (2022).

Albarrak, A. I. et al. Assessment of physician’s knowledge, perception and willingness of telemedicine in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 14, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2019.04.006 (2021).

Acharya, R. V. & Rai, J. J. Evaluation of patient and doctor perception toward the use of telemedicine in Apollo Tele Health Services, India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 5 (2016).

Buabbas, A. & Clarke, M. Investigation of the adoption of telemedicine technology in the Kuwaiti health system: Strategy and policy of implementation for overseas referral patients (2013).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques 3rd edn (Wiley, 1977).

Kursa, M. B. Boruta for those in a hurry (2022).

Alkureishi, M. A. et al. Clinician perspectives on telemedicine: observational cross-sectional study. JMIR Hum. Factors. 8, e29690. https://doi.org/10.2196/29690 (2021).

Ariens Lieneke, F. M. et al. Barriers and facilitators to eHealth use in daily practice: perspectives of patients and professionals in dermatology. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e300. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7512 (2017).

Rahman, S., Amit, S. & Al Kafy, A. Gender disparity in telehealth usage in Bangladesh during COVID-19. SSM Mental Health 2, 100054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100054 (2022).

Choi, J. S. et al. Telemedicine in otolaryngology during COVID-19: patient and physician satisfaction. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 167, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211041921 (2022).

Ilali, M. et al. Telemedicine in the primary care of older adults: a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Prim. Care. 24, 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02085-7 (2023).

Pinedo-Torres, I. et al. The doctor-patient relationship and barriers in non-verbal communication during teleconsultation in the era of COVID-19: A scoping review. F1000Res 12, 676. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.129970.1 (2023).

Ma, Q. et al. Usage and perceptions of telemedicine among health care professionals in China. Int. J. Med. Inf. 166, 104856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104856 (2022).

Barreiro, M. et al. Barriers to the implementation of telehealth in rural barriers to the implementation of telehealth in rural communities and potential solutions communities and potential solutions.

Onsongo, S. et al. Experiences on the utility and barriers of telemedicine in healthcare delivery in Kenya. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2023, 1487245. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/1487245 (2023).

Shardha, H. K. et al. Perceptions of telemedicine among healthcare professionals in rural tertiary care hospitals of rural Sindh, Pakistan: A qualitative study. Ann. Med. Surg. 86 (2024).

Glock, H. et al. Attitudes, barriers, and concerns regarding telemedicine among Swedish primary care physicians: a qualitative study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 9237–9246. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S334782 (2021).

SteelFisher, G. K. et al. Video telemedicine experiences in COVID-19 were positive, but physicians and patients prefer in-person care for the future. Health Aff. 42, 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01027 (2023).

Nies, S. et al. Understanding physicians’ preferences for telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Form. Res. 5, e26565. https://doi.org/10.2196/26565 (2021).

Asua, J. et al. Healthcare professional acceptance of telemonitoring for chronic care patients in primary care. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 12, 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-139 (2012).

Wong, H. et al. Age and sex-related comparison of referral-based telemedicine service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 1374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10373-2 (2023).

Haleem, A. et al. Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens. Int. 2, 100117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100117 (2021).

Jen-Hwa, P. Adoption of telemedicine technology by health care organizations: An exploratory study. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 12, 197–221. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327744JOCE1203_01 (2002).

Yuen, K. F. et al. The determinants of users’ intention to adopt telehealth: Health belief, perceived value and self-determination perspectives. J. Retail Consum. Serv. 73, 103346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103346 (2023).

Weinstein, R. S. et al. Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am. J. Med. 127, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.032 (2014).

Albahri, A. S. et al. IoT-based telemedicine for disease prevention and health promotion: state-of-the-art. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 173, 102873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2020.102873 (2021).

Yellowlees, P. M. et al. Telemedicine can make healthcare greener. Telemed e-Health 16, 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2009.0105 (2010).

Nnamoko, N. et al. Telehealth in primary health care: Analysis of Liverpool NHS experience, chapter 13. In Applied Computing in Medicine and Health (eds. Al-Jumeily et al.) 269–286 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2016).

Kissi, J. et al. Predictive factors of physicians’ satisfaction with telemedicine services acceptance. Health Inf. J. 26, 1866–1880. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458219892162 (2020).

Krousel-Wood, M. A. et al. Patient and physician satisfaction in a clinical study of telemedicine in a hypertensive patient population. J. Telemed. Telecare 7, 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1258/1357633011936417 (2001).

Felicia Gabrielsson-Järhult, S. K. & Josefsson, K. A. Telemedicine consultations with physicians in Swedish primary care: a mixed methods study of users’ experiences and care patterns. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 39, 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2021.1913904 (2021).

Demiris, G. Examining health care providers’ participation in telemedicine system design and implementation.

Wahezi, S. E. et al. Telemedicine and current clinical practice trends in the COVID-19 pandemic. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 35, 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2020.11.005 (2021).

Etz, R. S. et al. Telemedicine in primary care: lessons learned about implementing health care innovations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Fam. Med. 21, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2979 (2023).

Mahdi, S. S. et al. The promise of telemedicine in Pakistan: A systematic review. Health Sci. Rep. 5 (2022).

Hasson, S. P. et al. Rapid implementation of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and preferences of patients with cancer. Oncologist 26, e679–e685. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13676 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Institutional Review Board of King Edward Medical University, PSHC department of Punjab and University of the Punjab and Information Technology University of the Punjab for extending support for this research. Moreover, the authors are grateful to Dr. Ahmed Javed Qazi for extending administrative support and guidance for carrying out the research.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP: Lead author; Designing research, curation, conceptualization; methodology, formulating research, collecting, analyzing critical data. JS: Designing research methodology, analyzing results, and shaping the intellectual content of the paper.MAB: Data provision in the required format and management for the overall research framework.ZA: Statistical analysis of the data, validation and ensuring scientific accuracy.AH: Statistical analysis of the data and contribution in the manuscript.TT: Technical support, online surveys, manuscript preparation and data analysis.All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parvez, A., Saleem, J., Bhatti, M.A. et al. Boruta-driven analysis of telehealth amalgamation across healthcare stratifications with diffuse-dual-channel and tiered-gatekeeper systems. Sci Rep 14, 24784 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76295-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76295-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pricing Strategy and Coordination of Healthcare Service Dual-channel Supply Chain Considering Patients Referral

Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering (2025)