Abstract

To report the preliminary result of empiric embolization for angiographycally-negative lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) by using the pharmaco-induced vasospasm technique with or without the adjunctive use of intra-arterial multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT). 23 LGIB patients with positive MDCT findings but negative angiographic results underwent empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy. The presumed bleeding artery was semi-selectively catheterized, and a segment of bowel was temporarily spasmed with bolus injection of epinephrine and immediately followed by 4-h’ vasopressin infusion. The rebleeding, primary and overall clinical success rates were reported. MDCT showed 19 bleeders in the SMA territory and 4 bleeders in the IMA territory. Early rebleeding was found in 6 patients (26.1%): 2 local rebleeding, 3 from new-foci bleeding and 1 uncertain. Of the 10 small bowel bleeding patients, only 1 out of the 7 who underwent intra-arterial MDCT showed rebleeding, whereas 2 out of the 3 without intra-arterial MDCT rebled. No patients exhibited procedure-related major complications, including bowel ischemia and cardiopulmonary distress. The overall clinical success rate was 91.3% (21/23) with a 30-day mortality rate of 26.1% (2 of the 6 patients had early rebleeding). Empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy, when localized with/without adjunctive intra-arterial MDCT, seems to be a safe and effective method to treat angiographically-negative LGIB patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is defined as hemorrhage below the ligament of Treitz and includes jejunal, ileal, colonic, and rectal bleeding. Acute LGIB is estimated with an annual incidence of approximately 20–35 cases per 100,000 population1. The presentation of gastrointestinal bleeding can range from asymptomatic or mildly ill patients requiring only conservative treatments to severely ill patients requiring immediate intervention2. Acute massive LGIB, defined as requiring transfusion of at least four units of packed red blood cells with a clinical aide of systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or heart rate more than 110 beats per minute3, is a life-threatening emergency and a major cause of mortality. However, due to the intermittent nature of GI bleeding, detection rates of bleeding sites via angiography vary widely, 24–78%4. CTA is the gold standard in the timely and accurate diagnosis of GIBs, with high sensitivity and clinical efficacy in guiding the choice of the correct therapeutic strategy2. With the exception of a post polypectomy bleed where there is a clear opportunity for intervention, in other circumstances, the source of bleeding is often obscured by blood and colonoscopy does not help with either diagnosis or treatment5. Transcatheter arterial embolization is now widely accepted as the first-line therapy for LGIB as reported by many investigators and also from the updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guideline6,7,8,9,10,11,12, but the British Society of Gastroenterology has reported major bowel ischemic complications after embolization in 7–24% of angiographically positive cases13. As to the angiographically negative LGIB patients, empiric (prophylactic/blind) embolization is often regarded carrying higher complication rates, which may outweigh the clinical benefits. Thereafter, empiric embolization for non-tumor related LGIB is seldom reported in the literature14,15,16,17.

In a previous report18, pharmaco-induced vasospasm technique was introduced to treat acute LGIB in angiographically-positive patients with the advantages of easy performance, the ability to treat a short segment of bowel (versus only a single point as treated by conventional embolotherapy) and little risk of ischemic complications. Herein, we present a preliminary study of empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy in 23 CTA-positive but angiographically-negative LGIB patients.

Patients and methods

15 men and 8 women (aged 47–88 years, mean: 73.3 ± 12.1 years) received empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy to treat acute LGIB between January 2014 and December 2022. Informed consent was given by each patient/family prior to treatment and all methods in this study were performed in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective review (IRB: 22-CT8-29) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital. The patients’ informed consent of medical chart review in a retrospective review was waived in our hospital.

LGIB was first diagnosed by multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT), and angiography was performed only if positive MDCT was diagnosed. Patients with bleeding from the distal rectum were excluded from this study as many collateral blood supplies may exist. Patients with tumor bleeding or post-interventional bleeding were also excluded.15 in-patients and 8 out-patients were collected in this study with unstable hemodynamic status, defined as systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg in 13 patients at the time of angiography. 17 patients had normal coagulation status [International normalized ration (INR) < 1.25], while the other 6 patients had mild prolonged INR value (1.27–1.52). 10 patients had normal platelet count (≥ 150,000 ml). 12 patients had end-stage renal disease and underwent regular hemodialysis. 14 patients had positive contrast extravasation on the first MDCT study, while 6 patients on the 2nd exam, 1 patient on the 3rd exam, and 1 each on nuclear 99mTc-RBC-scintigraphy after 2 and 3 negative MDCT exams. Demographic data of theses 23 patients are listed in Table 1.

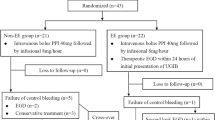

MDCT-aided catheter placement

The right common femoral artery was chosen as the routine puncture site. Based on the prior MDCT or nuclear scintigraphic findings, either the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) was catheterized by a 4-F RC1/RIM/J-curve angiocatheter (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). If no active contrast extravasation or abnormal vascular findings could be identified on the angiograms, a microcatheter (2.5-F Renegade, Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland; 2.4-F Progreat, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was coaxially inserted through a Y-adaptor for semi-selective catheterization into the presumed bleeding artery based on the prior positive imaging findings – e.g. the right colic artery for the ascending colon, the middle colic artery for the transverse colon, the ileocolic artery for terminal ileum or cecum, or the IMA for the descending/sigmoid colon or proximal rectum. As for other small bowel segments (jejunum or ileum), the vessel chosen to be spasmed was determined by the operators’ judgment based on the prior positive MDCT/scintigraphic findings. Intra-arterial MDCT was not initially part of the procedure but was later adopted in our angio-CT suite (Miyabi, Siemens, Germany) equipped with Artis Z angiographic machine and Definition AS, 20-slice spiral CT. The angio-CT was used to correspond the selected mesenteric territory with prior positive MDCT before vasospasm embolization, which was considered for better understanding the anatomy and identifying the selected vessel for embolization. The workflow of semi-selective catheterization in the presumed bleeding artery in the angiographycally negative patients based on the prior positive MDCT findings was summarized in Fig. 1. The protocol of the intra-arterial MDCT includes pre-contrast, arterial and venous phase images of around 20 cm span in the abdomen. Pure contrast medium (Omnipaque, 350 mg I/ml, GE Healthcare) was injected via the microcatheter with the rate of 0.5 ml/sec for 15 s. The parameters of CT scanning are 120 kV, 1.5 mm slice thickness with increment 1.0 mm and pitch 1. The arterial and venous phases start at the 10th and 20th sec, respectively. No breath-hold was required for these critically ill patients in the intra-arterial MDCT study.

Pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy

After catheter placement based on MDCT localization, pharmaco-induced vasospasm was performed by a bolus dose of epinephrine (0.4 mg diluted to 5 ml with normal saline) into a small mesenteric artery to induce vasospasm and was immediately followed by a continuous vasopressin (pitressin, Pfizer) infusion. The sheath was sutured on the skin and the diagnostic catheter was fixed together with the vascular sheath by a Tegaderm Transparent Film Dressing (3 M). Patients were then transferred to the ordinary ward for 4–5 h’ vasopressin infusion at a rate of 4–5 units/hour. The selected dose of vasoconstrictors and duration of vasospasm were based on authors’ prior experience18. The small vasopressin dose (20 units for 4–5 h’ infusion) will alleviate the systemic cardio-pulmonary distress complication whereas the infusion duration (4–5 h) was determined based on the fact that intra-arterial thrombolysis/embolectomy is regarded as life-saving procedure in cerebral infarct patients within 6 h’ golden period, that means the ischemic change of brain tissue within 6 h may be reversible. We consider that the intestine may tolerate the ischemic duration longer or at least equal to the brain tissue. The above procedures were performed by 3 interventional radiologists, each with 8 to 28 years of vascular and embolization experience.

Success

As patients often continued to pass dark stools for 24–48 h after cessation of active bleeding, early recurrent bleeding was defined as the need for blood transfusions requiring more than 2 units of packed red blood cells within 30 days of the procedure in order to stabilize hemoglobin levels19. As rebleeding did not always occur at the same focus site, recurrent bleeding was further categorized as local rebleeding and new-foci bleeding, according to either later MDCT or angiography.

Primary clinical success was defined as clinically successful hemostasis after the vasospasm embolization therapy. Overall clinical success was defined as clinically successful hemostasis that did not require further intervention (including re-intervention and observational follow-ups). The 30-day mortality rate was recorded retrospectively from medical charts.

Continuous data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The start date for follow-up tracking was the day of vasospasm. The study follow-up date ended on December 31, 2023.

Results

11 out of the 23 patients had undergone colonoscopy prior to angiography with neither a bleeding source being identified, nor successful hemostasis being achieved. Nineteen bleeders were found in the SMA territory [including, 5 in the jejunum, 7 in the ileum, 5 in the ascending colon, and 2 in the transverse colon (Fig. 2), and 4 bleeders were found in the IMA territory (including 2 in the descending colon and 1 each in the sigmoid colon and the proximal rectum).

an 85-year-old male patient with ESRD under regular hemodyalysis with massive bloody stool for days. (a) MDCT showed contrast extravasation at the hepatic flexure of colon (arrow). (b) SMA angiography did not show contrast extravasation or other vascular abnormality. The catheter tip (arrow) was placed at the middle colic artery (MCA) to perform empiric vasospasm therapy This patient had no recurrent bleeding by his 38-month follow-up (arrow) was placed at the middle colic artery (MCA) to perform empiric vasospasm therapy This patient had no recurrent bleeding by his 38-month follow-up.

Except 2 patients with the bleeding foci at the terminal ileum, a total of 10 patients had small bowel (jejunum or ileum) bleeding demonstrated on the initial MDCT. Initially, intra-arterial MDCT was not performed, and 2 out of 3 (66.7%) small-bowel bleeding patients showed early rebleeding. Intra-arterial MDCT was then adopted to correspond the small bowel (jejunum or ileum) bleeding localization with prior positive MDCT findings (Fig. 3). Only 1 of the 7 (14.3%) patients re-bled within 30 days. As to the patients’ survival, none of the 7 small bowel bleeding patients with adjunctive use of intraarterial MDCT died within 30 days, whereas 1 out of 3 small bowel bleeding patient without intraarterial MDCT localization died within 30 days.

a 73-year-old female patient under regular hemodialysis with bloody stool for one week. (a) MDCT showed contrast extravasation at the proximal jejunum (arrow). curved white arrow: transverse colon. (b) SMA angiography did not show contrast extravasation or other vascular abnormality. (c) Intra-arterial MDCT showed the contrast enhanced bowel segment via one of the proximal jejunal branch injection was away from the transverse colon (curved arrow). (d) Intra-arterial MDCT from another jejunal branch showed the corresponding contrast enhanced bowel segment was close to the transverse colon (curved arrow) similar to the anatomic relationship on the initial positive MDCT (A). Empiric vasospasm embolization was performed in this jejuna branch with clinical success.

Early rebleeding was found in 6 patients (26.1%) with 2 local rebleeding, 3 new-foci bleeding and 1 uncertain focus. Pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy was repeated in 1 each of the 2 local (Fig. 4) and 3 new-foci rebleeding patients with clinical success. Conservative medical treatments were performed in two patients with clinical success. One patient with local rebleeding at the mid-transverse colon received colonoscopic hemostasis, resulting in complication from colon perforation and expired 2 days after. The other patient complicated with shock and expired after local re-bleeding 13 days later.

83 years old male with lymphoma presented with persistent maelana for days. (a) MDCT showed contrast extravasation at the proximal jejunum (arrow). (b) SMA angiography did not show contrast extravasation or other vascular abnormality. The catheter tip was initially placed at one of the jejunal arteries (red curved arrow) for empiric vasospasm therapy. Unfortunately recurrent bleeding occurred at the next day. Repeated SMA angiography showed contrast extravasation from the other branch (black curved arrow). After a second vasospasm embolization therapy, there’s no recurrent bleeding for 7-month follow-up.

Primary clinical success for hemostasis was achieved in 17 of 23 (73.9%) with overall clinical success of 91.3% (21/23) in patients undergoing empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy. No patients exhibited complications of bowel ischemia or other procedure-related major complications, including cardiopulmonary distress.

Six patients died within 30 days resulting in a 26.1% 30-day mortality rate, of them 2 patients had early rebleeding. Therapeutic clinical outcomes are listed in Table 1. The causes of death were multi-organ failure in 2 patients, peritonitis due to a colonoscopic-procedure-related complication in 1 patient, and septic shock in 3 patients.

Excluding the 6 patients died within 30 days and 1 patient was transferred to local respiratory care center after stable clinical status, we were able to conduct ≧30-day clinical follow-ups on 16 patients. The mean follow-up period was 15.3 ± 14.4 months (range, 1.5 to 44 months). By the time of follow-up, no patients had developed evidence of bowel strictures, obstructions, or other conditions requiring later surgical resection.

Discussion

Advances in microcatheter technology have made super-selective embolization of small distal mesenteric arteries possible, with technical success rates of 69–100% reported in the literature6,7,8,9,10,11. Bowel ischemia remains a concern in super-selective embolization in angiographically-positive patients. A review20 in 2017 concluded that the pooled clinical success in 175 angiographically-positive LGIB patients treated with superselective N-Butyl Cyanoacrylate embolization had achieved 86.1%, with a bowel ischemia major complication rate of 6.1%. Bua-Ngam et al.11 and Nykänen et al.16 in recent reports concluded that major complications of ischemia (13 & 17%) remained a concern, even with a superselective embolization of the angiographically-positive LGIB.

Although Kim et al.4 concluded that 80% of a series of 75 angiographically-negative GI bleeding patients, in whom CTA was not performed, ceased bleeding spontaneously. Chan et al.21 also reported a 77.4% (48/62) of patients with lower GI bleeding who had an initial negative CTA did not rebled without the need for radiological or surgical intervention. In both Kim and Chan’s series4,21, all their patients had clinically presented with hematochezia but without images (MDCT or scintigraphy) identifying/localizing the bleeding. Both of the above situations were not exactly equivalent to those hematochezia patients who initially presented with positive MDCT or nuclear scintigraphy, in whom at least one positive active bleeding was detected on radiological studies, as in the patients of our present study. Angiographically-negative but MDCT-positive patients should be regarded as having at least a second bleeding episode, in which case the likelihood of spontaneous cessation of bleeding is much lower. In Kim’s series4, if early massive rebleeding occurred, a 50% mortality rate could ensue within a very short period of time. Chang et al.14 reported intra-arterial vasopressin infusion therapy (12–24 U/hr) via the SMA trunk for two days to treat angiographically-negative GI bleeding patients with significant different mortality rates between the angiographically positive and negative groups (20% and 42%, respectively; p < 0.05). Chang’s study14 implied high mortality rate of GI bleeding patients with negative angiographic findings if no effective therapy was applied, justifying the rationale for early intervention of angiographically-negative patients to prevent repeated hemorrhage. Their results also showed that high-dose proximal SMA trunk vasopressin infusion without further localization provided little clinical benefit.

As for non-tumor-related empiric LGIB embolization, Nykänen et al.16 reported a series of 53 patients in which 8 angiographically-negative patients underwent empiric (prophylactic) embolization, with a recurrent bleeding rate of 38%. This rebleeding rate was not significantly different than that of their angiographically active bleeding patients (p = 0.422), but complicated with bowel ischemia of 25%, leading to bowel resection. Nykänen’s results showed that, without precise localization, the risks of empiric (prophylactic) embolization for angiographically-negative LGIB may outweigh its clinical benefits. Li et al. retrospectively evaluated 126 patients of LGIB with 88 positive initial angiographies and 38 negative initial angiographies17. Of the latter, 18 patients underwent prophylactic (empiric) embolization procedures with metallic coils and/or slurry gelfoam pieces based on scintigraphic findings. They reported a 23.3% one-week re-bleeding rate and 4.9% bowel infarct complications in the initial angiography positive group, while 33.3% one-week re-bleeding rate and 4.2% bowel infarct were demonstrated following the prophylactic (empiric) embolization procedures, compared to 70% re-bleeding rate with no bowel infarct presented in the non-intervention group. They concluded that a definitive pre-angiographic localization of LGIB is crucial for decision making.

The precision by which the parent artery of bleeding is localized by MDCT findings is high for large bowel because of the fixed anatomic localization or relatively corresponding vascular relationship, e.g. the right colic artery for the ascending colon, the middle colic artery for the transverse colon, the ileocolic artery for terminal ileum or cecum, or the IMA for the descending/sigmoid colon or proximal rectum. However, for the small bowel (jejunum or ileum), the mobility and long length make determining the correctly non-contrast-extravasating artery difficult. Early in the study, 2 out of 3 small-bowel patients showed rebleeding within 30 days. To address this, we applied intra-arterial MDCT for closer localization in 7 small bowel bleeding cases and found it extremely helpful, resulting in only 1 rebleeding patient. This procedure is convenient and relatively quick to perform in the angio-CT suite. In addition, intra-arterial MDCT may increase the detection rate of smaller bleeding, since in animal-based models, catheter-based DSA cannot detect bleeding if it occurs at a rate of less than 0.5 mL per minute22.

Because the semi-selective vasospasm technique covered a short segment of bowel instead of a point, the chance of successful hemostasis in cases where bleeding foci could not be pinpointed was therefore increased. In the present series, 6 patients exhibited early rebleeding with new-foci bleeding in 3. Excepting the patient whose rebleeding source was uncertain, only 2 patients showed evidence of local rebleeding for up to 44 months’ follow-up. The early rebleeding rate in the present study was 26.1% or 19% excluding 30-day mortality patients as per Hur’s definition9. This compared favorably with the reported data in the literature for embolotherapy of angiographically-positive patients6,7,8,9,10,11,14,15,16,17,18,23,24.

Provocative mesenteric angiography (PMA) in the diagnosis and treatment of occult gastrointestinal hemorrhage was first described by Rosch et al. in 1988 who described it as pharmacoangiography25. The safety and efficacy of this technique remains a matter of debate, and requiring a multidisciplinary setting, involving interventional radiology, surgery and anesthesiology teams, ready to intervene in case of uncontrolled bleeding26. Before this technique, colonoscopy should be performed first in every patient to confirm the bleeding site is in or outside the inferior mesenteric territory (descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum). After angiography of the SMA/IMA is performed and deemed negative, then the provocative angiography is started with 5,000 units of heparin intravenously, followed by vasodilator (e.g. nitroglycerine, papaverine, tolazoline etc.) and/or thrombolytic agent [urokinase or tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)] administration into the target artery. After waiting 10 min, angiography is performed. The procedure may be repeated for 2 or 3 courses if contrast extravasation is still not demonstrated on the angiography27,28. A systematic review conducted in 2023 of the PMA for diagnosis or localization of occult GI bleeding revealed the average positivity rate for provocative angiography was 48.7%29. However, patients with negative results had a 33.1% incidence of recurrent bleeding within the follow-up period, indicating that PMA is not always successful in identifying the source of GIB. The concept and technique of PMA in occult LGI bleeding is different from that of our empiric (prophylactic) pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy for patients with MDCT-positive while angiographically-negative findings. Our empiric vasospasm therapy requires no need of colonoscopic study in advance and carries no risk of uncontrollable intestinal bleeding.

As to the different embolizers used in the LGI bleeding patients, the advantage of vasospasm technique for angiographically-positive LGI bleeding is easy to perform requiring only semi-selective catheterization of the bleeding artery instead of vasa rectum embolization by using permanent embolizers (metallic coils, NBCA glue or onyx) or absorbable Gelfom pieces. Thereafter, this technique can be performed even by interventionalists in training. The disadvantage of this technique may be associated with a higher local rebleeding rate in patients with high flow massive bleeding or coagulopathy patients. Even so, it still can be used for temporary cease of bleeding in the midnight or off day emergency. As to angiographically-negative LGI bleeding, based on the “first do no harm concept”, only vasospasm therapy for 4–5 h is suitable.

These preliminary results imply that empiric vasospasm therapy does achieve a certain degree of prevention for another episode of local rebleeding, provided it is performed in the appropriate region. Moreover, because up to 5 h of vascular spasm carries little risk of ischemic complications (all the spasmed vessels reopen with restoration of normal perfusion after discontinuation of vasopressin use), there is no significant harm to the patient. From this perspective, the clinical benefits of empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy assisted with MDCT localization and/or intra-arterial MDCT may far outweigh its potential risks. However, a large series of studies with significant case numbers is necessary to confirm this conclusion.

There were some limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective study from a single-institute with a relatively small number of patients. Second, the rate of spontaneous cessation of bleeding was uncertain in the MDCT-positive but angiographically-negative patients, which may have caused the overall clinical success to be overestimated. Lastly, as angio-CT equipment was adopted in this study, we could not answer the question if the corresponding localization effect can also be achieved or not by cone-beam CT use.

In conclusion, based on our preliminary data, empiric pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy localized by MDCT seems a safe and effective method to treat angiographically negative LGIB. The adjunctive application of intra-arterial MDCT in an angio-CT suite is also helpful for better localization and/or bleeding detection. However, the inclusions of all the above statements need further validation through larger multicentric studies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Farrell, J. J. & Friedman, L. S. Review article: The management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 21, 1281–1298 (2005).

Di Serafino, M. et al. The role of CT-angiography in the acute gastrointestinal bleeding: A pictorial essay of active and obscure findings. Tomography 8, 2369–2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography8050198 (2022).

O’Brien, J. W., Rogers, M., Gallagher, M. & Rockall, T. Management of massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Surgery (Oxford) 40(9), 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2022.05.020 (2022).

Kim, J. H. et al. Angiographically negative acute arterial upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Incidence, predictive factors, and clinical outcomes. Korean J. Radiol. 10(4), 384–390. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2009.10.4.384 (2009).

Tsay, C., Shung, D., Stemmer Frumento, K. & Laine, L. Early colonoscopy does not improve outcomes of patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Systematic review of randomized trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18(8), 1696-1703.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.061 (2020).

Bandi, R. et al. Superselective arterial embolization for the treatment of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 12(12), 1399–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61697-2 (2001).

Teng, H. C. et al. The efficacy and long-term outcome of microcoil embolotherapy for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Korean J. Radiol. 14(2), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2013.14.2.259 (2013).

Yata, S. et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization of acute arterial bleeding in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 24(3), 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2012.11.024 (2013).

Hur, S., Jae, H. J., Lee, M., Kim, H. C. & Chung, J. W. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-center experience with 112 patients. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 25(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2013.09.012 (2014).

Koo, H. J. et al. Clinical outcome of transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for control of acute gastrointestinal tract bleeding. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 204(3), 662–668. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.12683 (2015).

Bua-Ngam, C. et al. Efficacy of emergency transarterial embolization in acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A single-center experience. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 98(6), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2017.02.005 (2017).

Sengupta, N. et al. Management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: An updated ACG guideline. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118(2), 208–231. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002130 (2023).

Oakland, K. et al. Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 68(5), 776–789. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317807 (2019).

Chang, W. C. et al. Intra-arterial treatment in patients with acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding after endoscopic failure: Comparisons between positive versus negative contrast extravasation groups. Korean J. Radiol. 12(5), 568–578. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.568 (2011).

Muhammad, A. et al. Empiric transcatheter arterial embolization for massive or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding: Ten-year experience from a single tertiary care center. Cureus 11(3), e4228. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4228 (2019).

Nykänen, T., Peltola, E., Kylänpää, L. & Udd, M. Transcatheter arterial embolization in lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Ischemia remains a concern even with a superselective approach. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 22(8), 1394–1403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3728-7 (2018).

Li, S., Sun, S. & Wang, S. Safety and outcome of prophylactic embolotherapy for angiographic negative lower gastrointestinal bleeding. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 27, S11 (2016).

Liang, H. L. et al. Pharmaco-induced vasospasm therapy for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A preliminary report. Eur. J. Radiol. 83(10), 1811–1815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.06.032 (2014).

Drooz, A. T. et al. Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transcatheter embolization. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 14(9 Pt 2), S237–S242 (2003).

Kim, P. H., Tsauo, J., Shin, J. H. & Yun, S. C. Transcatheter arterial embolization of gastrointestinal bleeding with N-butyl cyanoacrylate: A systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 28(4), 522-531.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2016.12.1220 (2017).

Chan, V. et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 38, 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8 (2015).

Baum, S. Angiography and the gastrointestinal bleeder. Radiology 143(2), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.2.6978502 (1982).

Li, M. F. et al. Management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding by pharmaco-induced vasospasm embolization therapy. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 85(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000649 (2022).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Transcatheter arterial embolisation for acute lower gastrointestinal haemorrhage: A single-centre study. Eur. Radiol. 29, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5587-8 (2019).

Glickerman, D. J., Kowdley, K. V. & Rosch, J. Urokinase in gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Radiology https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.168.2.3260677 (1988).

Kokoroskos, N. et al. Provocative angiography, followed by therapeutic interventions, in the management of hard-to-diagnose gastrointestinal bleeding. World J. Surg. 44(9), 2944–2949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05545-8 (2020).

Kim, C. Y. Provocative mesenteric angiography for diagnosis and treatment of occult gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Int. J. Gastrointest. Interv. 7, 150–154. https://doi.org/10.18528/gii180034 (2018).

Thiry, G. J. H., Dhand, S., Gregorian, A. & Shah, N. Provocative mesenteric angiography: outcomes and standardized protocol for management of recurrent lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 26(3), 652–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-021-05131-w (2022).

Hegde, S., Sutphin, P. D., Zurkiya, O. & Kalva, S. P. Provocative mesenteric angiography for occult gastrointestinal bleeding: A systematic review. CVIR Endovasc. 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-023-00386-7 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the DSA technician team of the Department of Interventional Radiology of our hospital, who provide great assistance with the operations and image processing.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huei-Lung Liang, Ming-Feng Li and Chia-Ling Chiang. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has obtained IRB approval from (indicate the relevant board) and the need for informed consent was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, HL., Chiang, CL. & Li, MF. Empiric embolization by vasospasm therapy for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a preliminary report. Sci Rep 14, 25728 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76408-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76408-8