Abstract

Phase shifting profilometry (PSP) is widely used in three-dimensional (3D) optical metrology applications such as mechanical engineering, industrial monitoring, computer vision, and biomedicine because of its high measurement accuracy. In PSP, multi-frequency temporal phase unwrapping (TPU) plays a dominant role due to its high-accuracy measurement of surfaces with discontinuities and isolated objects. However, it requires a large number of fringe patterns. To reduce the number of required patterns, a new dual-frequency composite-pattern TPU method is developed, which needs only three patterns. The new method combines two fringe patterns of different frequencies into three composite fringe patterns, reconstructs rough 3D points by demodulating the low-frequency fringe pattern using geometric constraints, and reprojects it to obtain a rough low-frequency absolute phase, which is then refined to correct edge errors. Finally, the high-frequency wrapped phase is unwrapped under the guidance of the refined low-frequency phase, thereby the accurate 3D points are reconstructed based on stereo-vision technology. Experimental results demonstrated that the proposed method can achieve 3D surface measurement with only three images, which greatly improves the measurement efficiency. The proposed method has great application potential for the rapid 3D measurement of discontinuous surfaces and isolated objects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Railway wheels are essential for train safety as they bear the load and guide the train. Defects such as wear or surface damage can cause severe issues, including axle breakage or structural failures, potentially leading to derailments1. Therefore, inspection of wheel treads is essential for safety. The detection of train wheelsets is mainly divided into two categories, contact measurement and non-contact measurement2. Traditional railway wheel inspections typically utilize manual, contact-based approaches, which are often time-consuming and can easily lead to operator fatigue. On the other hand, the use of non-contact methods in optics, mechanics, and electronics provides the advantages of higher accuracy, minimum environmental impact, and real-time processing3.

Full-field fringe projection methods play an important role in non-contact three-dimensional (3D) surface-shape measurement. These methods are increasingly used in various applications, including mechanical engineering, industrial inspection, robot vision, medicine, and entertainment4,5,6,7. Phase-shifting profilometry (PSP) has become a crucial tool in the nondestructive testing and non-contact measurement industry8,9,10,11. PSP typically requires the projection of three frames of phase-shifted fringe patterns onto the object. These deformed fringe patterns, captured by the camera, generate phase values ranging from –π to π12. To address phase ambiguity, several methods are employed, including spatial phase unwrapping (SPU), temporal phase unwrapping (TPU), and the application of geometric constraints.

In spatial phase unwrapping, the wrapped phase values of two adjacent pixels are compared point by point in space13. If the phase difference between two adjacent points is between –π and π, the current phase value remains unchanged. If the difference is greater than π, subtract 2π from the current phase value; Similarly, if the difference is less than –π, 2π is added to the current phase. However, the dependency on path selection in numerous phase unwrapping algorithms can lead to the propagation of phase errors across the image13. D.G. Abdelsalam Ibrahim14 proposed a new two-step phase shift interferometry (TSPS), which can reconstruct the object surface with only two interferograms. However, this method may fail for discontinuous surfaces and multiple isolated objects.

Temporal phase unwrapping15,16,17,18 techniques address this issue by employing extra wrapped phase maps, which provide additional details of the fringe orders. In traditional dual-frequency TPU methods for PSP19,20, at least six patterns are needed. Using the unit-frequency phase map as a reference, the fringe order in the high-frequency phase map is determined, which is essential for the process of 3D surface reconstruction21. Various dual-frequency strategies focus on minimizing the number of necessary patterns. One method employs a dual-frequency pattern strategy to reconstruct 3D shapes. It needs only five fringe patterns to solve the ambiguity problem phase unwrapping by combining high-frequency and unit-frequency fringe patterns22. To reduce the required patterns to four, a novel method employs self-unwrapping phase-shifting (SUPS) for efficient 3D shape measurement. It only needs four images to complete the phase unwrapping, which avoids the extra pattern to accurately determine the fringe orders through a new space-varying phase shift (SPS) algorithm23. Another paper presents a phase-shifting temporal unwrapping (PS-TPU) algorithm for fringe projection profilometry, requiring four patterns to achieve robust and fast 3D shape measurement by embedding phase shifts into a single quasi-cosine pattern for fringe order generation24. However, in the dual-frequency method, the phase accuracy of high-frequency fringe patterns is still limited. In order to improve the measurement accuracy, the third group of fringe patterns with higher frequency are introduced, especially for the measurement of isolated and surface discontinuous objects. However, the large number of images required poses a challenge for fast 3D measurement of surface discontinuities and isolated objects25.

To address this issue, researchers have developed unwrapping methods based on geometric constraints26,27,28 to remove the phase ambiguity of each pixel without requiring additional patterns as in temporal phase unwrapping. Geometry-constraint methods can reconstruct the object surface directly from wrapped phase maps. This is achieved by constraining the candidate 3D points to a subset in a pre-defined measurement volume to reduce the search when determining point correspondences between camera and projector images. A system based on the geometric constraint method usually consists of a projector and two cameras. If all the pixels in one camera image can find the corresponding points in the projector image, stereo vision technology can be used to reconstruct the 3D points of the object according to the internal and external parameters of the camera and the projector26. The epipolar line is typically used to limit the search for matching points. However, when this search is only dependent on the wrapped phase value, multiple potential matches could be identified along the epipolar line within a given measurement volume27. To minimize the number of potential candidate points within the measurement range and guarantee the reliability of corresponding points, a lower fringe frequency is typically utilized in projections28. However, a lower fringe frequency means that the lower measurement accuracy21. On the other hand, while high-frequency fringe patterns increase measurement accuracy, they will introduce multiple candidate points within the measurement volume, making it difficult to identify the correct correspondences for accurate reconstruction29. Therefore, there is generally a trade-off in selecting the fringe pattern frequency in geometry-constraint-based techniques.

To address this limitation, we propose a dual-frequency composite-pattern temporal phase unwrapping (DC-TPU) method for fast 3D measurement of surface discontinuities and isolated objects. It combines phase-shifting fringes with two different frequencies into three composite patterns. The low-frequency pattern is designed to provide just one corresponding point candidate in the measurement volume, which assists in dependable point selection. Using geometric constraints to reconstruct rough 3D points, the rough 3D points are reprojected onto the projector image plane to obtain the coarse low-frequency absolute phase. The errors that occur at the edges of the wrapped phase are corrected by the proposed phase refinement method, by searching for the real corresponding points in the left camera and the projector. The high-frequency absolute phase is obtained from the low-frequency absolute phase, and the reconstruction of precise 3D points is obtained based on the stereo-vision techniques. The proposed technique, requiring only three dual-frequency composite patterns, accurately measures 3D surface shapes and effectively addresses objects with surface discontinuities. Our main contributions are summarized as follows.

-

1)

The proposed method reduces the number of projected fringe images compared to traditional temporal phase unwrapping algorithms while maintaining high measurement accuracy.

-

2)

The proposed method bridges the reliability of low-frequency fringe patterns with the high accuracy of high-frequency patterns, ensuring both reliability and precision in 3D reconstruction.

-

3)

The phase refinement method effectively corrects errors in the low-frequency absolute phase, improving the accuracy of the final 3D reconstruction.

The organizational structure of this manuscript is as follows: Sect. 2 explains the principle of the proposed method in detail; Sect. 3 gives the results of comparative experiments and quantitative experiments; and Sect. 4 summarizes this paper.

Methods

PSP using temporal phase unwrapping

Phase-shift algorithm has been widely used in optical measurement because of its high accuracy and robustness. A variety of phase shift algorithms have been proposed, which have different requirements for the number of fringe patterns and the phase shift between fringe patterns. The three-step phase shift algorithm minimizes this requirement and requires the least number of patterns for effective phase extraction, which is beneficial to high-speed measurement applications. These three fringe patterns can be expressed mathematically as:

where \(I^{\prime}\left( {x,y} \right)\) represents the average intensity, \(I^{\prime\prime}\left( {x,y} \right)\) denotes the intensity modulation, and \(\varphi\) is the phase to be determined. Solving these three equations concurrently results in,

The arctangent function in Eq. (4) gives the wrapped phase in the range of (− π, π) with \(2\pi\) discontinuities. To obtain the desired continuous phase \({\Phi }\left( {x,y} \right)\) , a phase unwrapping algorithm is employed to determine \(k\left( {x,y} \right)\), the number of \(2\pi\) to be added for each point, that is

where \(k\left( {x,y} \right)\) is an integer, usually called the fringe order. The fundamental technique of multi-frequency TPU involves phase unwrapping using two other phase maps, each with a distinct fringe frequency. The wrapped phase maps with unit-frequency \(\varphi_{u} \left( {x,y} \right)\), low-frequency \(\varphi_{l} \left( {x,y} \right)\), and high-frequency \(\varphi_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) are obtained by Eq. (4), respectively. The calculation of fringe orders involves \(k_{l} \left( {x,y} \right)\) for the low-frequency phase map and \(k_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) for the high-frequency phase map, which can be described as:

where \(F_{u}\) is the fringe period of unit-frequency, and \(F_{u}\) = 1,\(F_{l}\) is the fringe period of low-frequency,\(F_{h}\) is the fringe period of high-frequency. For unit-frequency patterns, \({\Phi }_{u} \left( {x,y} \right)\) is the absolute phase, which includes just one fringe period, and \({\Phi }_{u} \left( {x,y} \right) = \varphi_{u} \left( {x,y} \right)\). The absolute phase of low-frequency is \({\Phi }_{l} \left( {x,y} \right)\). \({\Phi }_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) represents the absolute phase of high-frequency, which can be obtained using Eq. (5) and used for the final 3D reconstruction.

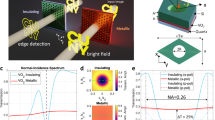

Dual-frequency composite-pattern

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, three images are created by vertically modulating fringe patterns on low and high frequencies with different carrier frequencies and then combining them. The dual-frequency fringe patterns represent two sets of three-step phase-shifted fringe patterns at different frequencies, with phase shifts of \(- \tfrac{2}{3}\pi\), \(0\) and \(- \tfrac{2}{3}\pi\) respectively. The carrier fringe patterns are two sets of gratings at different frequencies. The purpose of these carrier fringe patterns is to make it easier to separate the low-frequency and high-frequency deformed patterns in the frequency spectrum. Since the spectrum components are staggered in the spectrum of the composite deformed pattern, the low-frequency and high-frequency deformed patterns with background light can be demodulated easily.

The deformed patterns captured by the camera can be expressed as:

where \(n = 1,2,3\),\(I_{l} \left( {x,y} \right)\),\(I_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) represents the deformed patterns of both low-frequency and high-frequency fringe patterns respectively, and \(f_{x1}\),\(f_{x2}\) are two different carrier frequencies, \(R\left( {x,y} \right)\) represent the reflectivity, while \(D\left( {x,y} \right)\) and \(C\left( {x,y} \right)\) are the contrast and background intensity, respectively, typically considered as constants. The outcome of the Fourier transform applied to Eq. (8) can be expressed as:

where \(r\) and \(c\) represent \(R\left( {x,y} \right)\) and \(C\left( {x,y} \right)\),respectively. The spectrum of \(F_{n} (f_{x} ,f_{y} )\) has 13 components as depicted in Fig. 2. The zero-frequency spectrum component \(rc\delta (f_{x} ,f_{y} )\) and the other spectral components of the composite fringe pattern are sufficiently separated. The spectrum components \(F_{l}^{ - } \left( {f_{x} + f_{x1} ,f_{y} } \right)\) and \(F_{h}^{ - } \left( {f_{x} + f_{x2} ,f_{y} } \right)\) can be extracted using appropriate filters, and the modulus of their inverse Fourier transform can be expressed as30:

The wrapped phase \(\varphi_{l} (x,y)\) and \(\varphi_{h} (x,y)\) can be calculated from Eq. (4).

Temporal phase unwrapping based on phase refinement

To first obtain the low-frequency absolute phase, the geometry-constraint-based method is used. Utilizing geometry-constraint-based methods (Fig. 3), any point \(P_{L}\) in the left camera corresponds to a sight of light in three-dimensional space. This line is reprojected onto the image plane of the projector and the right camera respectively, corresponding to the two epipolar lines \(e_{P}\) and \(e_{R}\) respectively. Assuming that the fringe periods is \(K\), generating \(K\) potential 3D positions of the object surface with the same phase value, and there are \(K\) candidate points with the same phase as \(P_{L}\) on the epipolar \(e_{P}\) and \(e_{R}\). Among the candidate positions, only one is correct and found directly on the object surface. The accurate corresponding point is determined through the application of geometric constraints. By establishing a depth range \(\left( {Z^{\min } < Z^{w} < Z^{\max } } \right)\), we can exclude all 3D candidate positions that are located outside of this defined volume. The smallest fringe-pattern wavelength of the low-frequency fringe patterns is determined31 to ensure only one neighboring 3D position \((Q_{k} )\) within the measurement volume.

Diagram of geometry constraints and correspondence. (\(O_{L}\), \(O_{P}\) and \(O_{R}\) represent the left camera, projector, and right camera light centers; \(e_{P}\) and \(e_{R}\) are projector and the right camera epipolar lines; and \(Q_{k - 1} , \ldots Q_{k + 1}\) represent points on the line of sight).

The 3D world coordinates \(\left( {X^{w} ,Y^{w} ,Z^{w} } \right)\) can be converted into 3D projector coordinates \(\left( {X^{p} ,Y^{p} ,Z^{p} } \right)\) through:

where \(M\) and \(T_{M}\) represent the rotation and translation extrinsic-parameter matrix of the projector, respectively. Therefore, the calculation for normalized projection onto the image plane of the projector can be carried out as follows:

The fringe order \(k_{l} (x,y)\) on the projector can be computed as:

where \(W_{P}\) and \(N_{l}\) are the wide resolution of the projector and the fringe period of the projected pattern. The low-frequency absolute phase \({\Phi }_{l} (x,y)\) can be expressed as:

For a given point \(P_{L}\) in the left camera image, its corresponding point \(P_{P}\) in the projector is calculated by re-projecting the 3D position \(Q_{k}\) onto the projector image plane (Fig. 3). However, due to calibration errors and phase errors in the left camera and projector, the calculated corresponding point \(P_{P}\) may not be in the correct position (Fig. 4).

A phase refinement method is proposed to correct the low-frequency absolute phase. To find a point \(P^{\prime}_{P}\) on the projector’s epipolar line \(e_{P}\) that has the same phase value as point \(P_{L}\) from the left camera. The wrapped phase difference \(\Delta \varphi (x,y)\) of the same point on the left camera and projector image can be expressed as:

The difference of the wrapped phase needs to be corrected as shown in Eqs. (17) and (18):

The low-frequency absolute phase can be refined as:

However, the point cloud obtained by the low-frequency absolute phase has limited accuracy32. The use of the high-frequency absolute phase would increase the measurement accuracy. The high-frequency wrapped phase is unwrapped under the guidance of the refined low-frequency phase, thereby the accurate 3D points are reconstructed based on stereo-vision technology. The high-frequency absolute phase \({\Phi }_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) can be calculated by:

where \(m\) is \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${F_{h} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{h} } {F_{l} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${F_{l} }$}}\), the high-frequency absolute phase \({\Phi }_{h} \left( {x,y} \right)\) is used to reconstruct the final 3D surface of an object.

The proposed DC-TPU method can be summarized into these three steps, and the complete process is shown in Fig. 5.

-

The three deformed composite patterns captured by the left and right cameras are filtered to obtain the low-frequency and high-frequency wrapped phases respectively.

-

The low-frequency fringe patterns are demodulated to reconstruct rough 3D points using geometric constraints, and the 3D points are reprojected to the projector image plane to obtain the coarse low-frequency absolute phase. The phase refinement method is applied to refine the low-frequency absolute phase.

-

The high-frequency absolute phase is obtained from the low-frequency absolute phase, and the 3D reconstruction of the high-frequency is obtained by using stereo vision.

Experiments

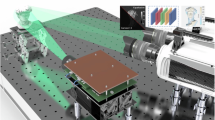

To verify the performance of the DC-TPU method, a 3D shape measurement system utilizes a digital-light-processing (DLP) projector (Wintech PRO4500) projector with a resolution of 912 × 1140, and a black-and-white camera (Basler acA1920-40gm) with 1920 × 1200 resolution and a lens with a 16 mm focal length. The calibration of the projector-camera system was accomplished using a stereo-vision model and then stereo-vision technology was used for 3D surface reconstruction.

Determination of the optimal size of filter window

Numerous filtering window functions are widely used in signal processing, each with distinct passband edge suppression characteristics. These differences can influence the frequency resolution and the degree of spectrum leakage observed. Choosing a window function that achieves an optimal balance can significantly improve the overall quality of the filtering process. This study evaluates the rectangular, triangular, Hamming, Blackman, and Hanning windows to design an optimal mixed filter based on their performance in various orientations.

The process starts by uniformly applying a rectangular filtering window in the vertical direction, with a vertical width of Ly = 1920 pixels for a 1920 × 1200 pixels pattern, ensuring complete information and consistent noise in this direction. Our analysis examines the relationship between the horizontal widths of various window types and their filtering effectiveness. The mean absolute error (MAE) distributions corresponding to the horizontal widths are depicted in Fig. 6(a), while the root mean square error (RMSE) distributions are illustrated in Fig. 6(b). As we can observe, there is a minimum width due to the edge cutoff of the rectangular window and the higher frequency resolution when the window is small. If the width is less than this value, the spectrum component after filtering will be seriously lacking. In the range of 25 to 36 pixels, the rectangular window retains more useful spectrum information compared to the triangular, Hamming, Blackman, and Hanning windows, which exhibit spectrum leakage. On the contrary, for widths between 80 to 160 pixels, these four windows demonstrate superior filtering stability and precision. The Blackman window, with an optimal width of Lx = 125 pixels, provides the highest filtering accuracy and is also set as the horizontal filtering window with the same width. Further research on how the vertical width Ly affects filtering shows that as Ly increases, the MAE and RMSE values first decrease and then increase, as depicted in Fig. 7(a) and 7(b). The primary issue is that a very narrow width leads to spectrum loss, while a very wide width increases noise, resulting in a decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The Hanning window, with an optimal width of Ly = 1000 pixels, provides the best filtering accuracy in this direction. Therefore, to extract spectrum components effectively, we design an optimal mixed filtering window. This window integrates a Blackman window with optimal horizontal width and a Hanning window with optimal vertical width.

Measurement accuracy evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the DC-TPU method, experiments were carried out on a double-sphere object (Fig. 8(a)) with true radii Ra = 25.407 mm and Rb = 25.408 mm, and a distance between centers of 150.000 ± 0.008 mm. Figure 8(b) shows a captured dual-frequency composite-pattern image. Further, Fig. 8(c) shows a detailed feature marked by a box in Fig. 8(a). Figure 9 presents the results of 3D reconstruction obtained by using our proposed method. The MAE of the radii are 0.064 mm and 0.054 mm, respectively; the RMSE of the radii are 0.090 mm and 0.084 mm, respectively; and the MAE of the distance between the centers of the sphere is 0.412 mm.

Measurement of a spherical object

For comparison, the object was measured using three different TPU methods: multi-frequency (9 frames), dual-frequency geometric constraint (6 frames), and single-frequency geometric constraint (3 frames), all within the same experimental setup. In the traditional multi-frequency technology, the unit-frequency fringe patterns, the low-frequency fringe patterns and the high-frequency fringe patterns are 1, 8 and 57 periods per frame, respectively. For the dual-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method, the frequencies of the low-frequency fringe patterns and high-frequency fringe patterns were 8 and 57 periods per frame, respectively. The low-frequency fringe patterns were determined31 to ensure only one neighboring 3D position \((Q_{k} )\) within the measurement volume. The frequency for the single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method was 8 periods per frame. For the DC-TPU method, the frequencies of low-frequency fringe patterns and high-frequency fringe patterns are 8 and 57 periods per frame, respectively.

Experiments to verify the effectiveness of the proposed phase refinement method were conducted. As shown in Fig. 10(a), one dual-frequency composite-pattern image captured by the left camera; Fig. 10(b) shows a detailed feature marked by a box in Fig. 10(a), while Fig. 10(c) is the low-frequency images filtered from (a), Fig. 10(d) is the high-frequency images filtered from (a). As shown in Fig. 10(e), the low-frequency absolute phase of the left camera before refined, the errors occur at the edges of the wrapped phase. Figure 10(f) shows the cutaway views of the 800th row in Fig. 10(e). As shown in Fig. 10(g) the low-frequency absolute phase of the errors is corrected by the proposed phase refinement method, Fig. 10(h) shows the cutaway views of the 800th row in Fig. 10(g). The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed phase refinement method significantly improved the accuracy of low-frequency phases. Although the composite pattern requires more time to extract the patterns, fewer projected fringe patterns are required compared to the conventional temporal phase unwrapping method using 9 fringe images, thus reducing the acquisition time.

The proposed phase refinement method, (a) one dual-frequency composite-pattern image captured by the left camera, (b) the local feature marked by a box in Fig. 10(a), (c) the low-frequency images filtered from (a), (d) the high-frequency images filtered from (a), (e) the low-frequency absolute phase of the left camera before refined, (f) cutaway views of the 800th row in Fig. 10(e), (g) the low-frequency absolute phase of the left camera after refined, (h) cutaway views of the 800th row in Fig. 10(g).

The 3D surface reconstructions for the conventional multi-frequency TPU, dual-frequency geometric-constraint TPU, single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU, and the proposed DC-TPU method were successful, as shown in Fig. 11(a)–(d), respectively. Figure 11(e)–(h) illustrates the measurement errors for the conventional multi-frequency TPU, dual-frequency geometric-constraint TPU, single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU, and DC-TPU method, respectively. As shown in Fig. 11(i)–(l), the detailed feature is marked by a box in Figs. 11(e)–(h), respectively. Furthermore, Fig. 12 displays the cutaway views at the 800th row from the results in Fig. 11(a)–(d). The experimental results show that although the proposed method had slightly lower measurement accuracy compared to the traditional multi-frequency TPU and dual-frequency geometric-constraint methods, it offers a significant advantage by requiring only three patterns, in contrast to nine or six. Moreover, the results demonstrate that the proposed method provides higher accuracy than the traditional single-frequency geometric constraint method.

The measurement result of surface reconstruction of the object, (a) Conventional multi-frequency TPU method, (b) Dual-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method and, (c) Single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method, (d) DC-TPU method; (e)–(h) are the error of Figs. (a)-(d) compared with the three-frequency sixteen-step phase shift algorithm, respectively. (i)–(l) are the enlarged image of a small part of the measurement errors in Figs. (e)–(h), respectively.

Cross-sectional views of the reconstructions at the 800th row in Fig. 11(a), (b), (c), and (d).

Table 1 presents a comparison of the MAE and RMSE for the four measurement methods. Only the data with \(3\delta\) of the statistical data are considered valid21. The traditional multi-frequency TPU technique is widely used for its high accuracy, exhibiting the smallest MAE and RMSE. However, it requires nine patterns for reconstruction. The dual-frequency geometric-constraint method demonstrates high precision but necessitates the use of six patterns for reconstruction. In contrast, the single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method exhibits larger errors and requires three patterns for reconstruction. Our proposed method offers a balance between accuracy and efficiency. Although it has larger errors compared to the traditional multi-frequency TPU method and the dual-frequency geometric-constraint method, its accuracy is better than the single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method. The most significant advantage of our proposed method is its efficiency, which could achieve a 3D surface measurement using only three images.

Multiple isolated-object measurement

To evaluate the performance of the DC-TPU method with isolated objects, experiments were conducted on two distinct objects that were spatially isolated. Figure 13(a) and (c) show one of the dual-frequency composite pattern images with two sets of isolated objects. Further, Fig. 13(b) and Fig. 13(d) show a detailed feature marked by a box in Fig. 13(a) and Fig. 13 (c), respectively. Similarly, Fig. 13(e) and (g) illustrate a low-frequency image, while Fig. 13(f) and (h) show a high-frequency image with two groups of isolated objects. The 3D reconstructions using the DC-TPU method are shown in Fig. 13(i) and (j), respectively. The experimental results show that the proposed method can measure the discontinuous surface of isolated objects.

Multiple isolated-object 3D reconstruction results: (a) and (c) are two captured dual-frequency composite-pattern images, (b) and (d) are the local feature marked by a box in Fig. 13(a) and Fig. 13(c), (e) and (g) are low-frequency images filtered respectively from (a) and (c), (f) and (h) are high-frequency images filtered from (a) and (c) respectively, and (i)-(j) are 3D reconstruction images of two objects respectively.

Measurement of the train wheel tread

To illustrate the proficiency of the DC-TPU method in train wheel tread measurement, an experimental setup was established in a train wheel workshop, which is displayed in Fig. 14. Additionally, Fig. 15(a) presents one of the deformed composite fringe images captured by the camera. Figure 15(b) shows a detailed feature marked by a box in Fig. 15(a). The low-frequency and high-frequency fringe patterns filtered from Fig. 15(a) are shown in Fig. 15(c) and Fig. 15(d), respectively. The 3D reconstruction of the train wheel tread, achieved through the DC-TPU method and presented in Fig. 16, demonstrates the capability of the proposed method, although it also shows the presence of invalid points caused by the filtering of the wheel edge.

Conclusion

A DC-TPU technique is developed for fast 3D surface measurement of objects with discontinuous surfaces and multiple isolated objects. The main idea is that low-frequency fringe patterns serve as a bridge, connecting the reliability of candidate points obtained from low-frequency patterns with the high accuracy achieved by high-frequency fringe patterns. Compared with the traditional temporal phase unwrapping algorithm, the proposed method effectively reduces the number of projected fringe images while still maintaining high measurement accuracy. Firstly, two sets of phase-shifted fringes of different frequencies are combined into three composite fringes and projected onto the object to be measured. The deformed fringes collected by the camera are demodulated using a suitable filter. The optimal filter window size is determined by vertical and horizontal analysis to ensure reliable phase accuracy. The low-frequency deformed fringe patterns and high-frequency deformed fringe patterns are obtained. Secondly, the low-frequency fringe patterns are demodulated to reconstruct rough 3D points using geometric constraints, and the 3D points are reprojected to the projector image plane to obtain the coarse low-frequency absolute phase. The errors of the low-frequency absolute phase are corrected by the proposed phase refinement method. Finally, under the guidance of the refined low-frequency absolute phase, the high-frequency wrapped phase is unwrapped, and the accurate 3D points are reconstructed based on stereo vision technology. The experimental results demonstrated that the DC-TPU method has better reconstruction accuracy than the single-frequency geometric-constraint TPU method. Although its measurement accuracy is slightly lower than the traditional multi-frequency TPU method and dual-frequency geometric constraint method, only three images are needed for reconstruction. Additionally, the 3D shape of multiple isolated objects and train wheel treads were reconstructed successfully by the proposed method. The proposed method may have some limitations when measuring the edge of an object because the filtering operation will inevitably cause the loss of useful information. A fast fringe projection 3D measurement technology without filtering in the spectral domain would need further investigation.

Data availability

Data can be shared upon reasonable request and correspondence should be addressed to Y.Z.

References

Hou, M., Liu, F. & Hu, X. Typical wheel–rail profile change rules and matching characteristics of high speed railway in China. RS 1, 289–306 (2022).

Ran, Y., He, Q., Feng, Q. & Cui, J. High-Accuracy On-Site Measurement of Wheel Tread Geometric Parameters by Line-Structured Light Vision Sensor. IEEE Access 9, 52590–52600 (2021).

Chen, Y., Li, Y., Niu, G. & Zuo, M. Offline and Online Measurement of the Geometries of Train Wheelsets: A Review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–15 (2022).

Chen, R., Xu, J. & Zhang, S. Comparative study on 3D optical sensors for short range applications. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 149, 106763 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Large viewing angle holographic 3D display system based on maximum diffraction modulation. Light Adv. Manuf. 4, 1 (2023).

Lin, S., Zhu, H. & Guo, H. Harmonics elimination in phase-shifting fringe projection profilometry by use of a non-filtering algorithm in frequency domain. Opt. Express 31, 25490 (2023).

Zhu, S., Wu, Z., Zhang, J., Zhang, Q. & Wang, Y. Superfast and large-depth-range sinusoidal fringe generation for multi-dimensional information sensing. Photon. Res. 10, 2590 (2022).

Gorthi, S. S. & Rastogi, P. Fringe projection techniques: Whither we are?. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 48, 133–140 (2010).

Geng, J. Structured-light 3D surface imaging: a tutorial. Adv. Opt. Photon. 3, 128 (2011).

Zhang, S. Recent progresses on real-time 3D shape measurement using digital fringe projection techniques. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 48, 149–158 (2010).

Su, X. & Zhang, Q. Dynamic 3-D shape measurement method: A review. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 48, 191–204 (2010).

Su, X. & Chen, W. Reliability-guided phase unwrapping algorithm: a review. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 42, 245–261 (2004).

Yang, T. & Gu, F. Overview of modulation techniques for spatially structured-light 3D imaging. Optics & Laser Technology 169, 110037 (2024).

Abdelsalam Ibrahim, D. G. Fast phase-shifting technique for 3-D surface micro-topography measurement. Measurement 135, 106–111 (2019).

Zhang, S. Absolute phase retrieval methods for digital fringe projection profilometry: A review. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 107, 28–37 (2018).

Zuo, C. et al. Phase shifting algorithms for fringe projection profilometry: A review. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 109, 23–59 (2018).

Wan, Y., Cao, Y. & Kofman, J. High-accuracy 3D surface measurement using hybrid multi-frequency composite-pattern temporal phase unwrapping. Opt. Express 28, 39165 (2020).

Wan, Y., Cao, Y., Liu, X., Tao, T. & Kofman, J. High-frequency color-encoded fringe-projection profilometry based on geometry constraint for large depth range. Opt. Express 28, 13043 (2020).

Xing, S. & Guo, H. Temporal phase unwrapping for fringe projection profilometry aided by recursion of Chebyshev polynomials. Appl. Opt. 56, 1591 (2017).

Zhao, H., Chen, W. & Tan, Y. Phase-unwrapping algorithm for the measurement of three-dimensional object shapes. Appl. Opt. 33, 4497 (1994).

Zuo, C., Huang, L., Zhang, M., Chen, Q. & Asundi, A. Temporal phase unwrapping algorithms for fringe projection profilometry: A comparative review. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 85, 84–103 (2016).

Liu, K., Wang, Y., Lau, D. L., Hao, Q. & Hassebrook, L. G. Dual-frequency pattern scheme for high-speed 3-D shape measurement. Opt. Express 18, 5229 (2010).

Zeng, J. et al. Self-Unwrapping Phase-Shifting for Fast and Accurate 3-D Shape Measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–12 (2022).

An, H., Cao, Y., Zhang, Y. & Li, H. Phase-Shifting Temporal Phase Unwrapping Algorithm for High-Speed Fringe Projection Profilometry. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, (2023).

Xu, J. & Zhang, S. Status, challenges, and future perspectives of fringe projection profilometry. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 135, 106193 (2020).

Heist, S. et al. GOBO projection for 3D measurements at highest frame rates: a performance analysis. Light Sci Appl 7, 71 (2018).

Tao, T. et al. Real-time 3-D shape measurement with composite phase-shifting fringes and multi-view system. Opt. Express 24, 20253 (2016).

Guo, Y. et al. Fast and accurate 3D face reconstruction based on facial geometry constraints and fringe projection without phase unwrapping. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 159, 107216 (2022).

Liu, X. & Kofman, J. Real-time 3D surface-shape measurement using background-modulated modified Fourier transform profilometry with geometry-constraint. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 115, 217–224 (2019).

An, H., Cao, Y., Wu, H., Zhang, H. & Li, H. The spatial phase-shifting measuring profilometry based on dual-frequency grating. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 143, 106638 (2021).

Liu, X. & Kofman, J. High-frequency background modulation fringe patterns based on a fringe-wavelength geometry-constraint model for 3D surface-shape measurement. Opt. Express 25, 16618 (2017).

Lee, H. & Cho, H. Stereo Moiré Technique: A Novel 3-D Measurement Method Using a Stereo Camera and a Digital Pattern Projector. International Journal of Optomechatronics 1, 209–230 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Key international (regional) cooperation and exchange projects of the Nature Fund (61960206010);

Funding

Key international (regional) cooperation and exchange projects of the Nature Fund, 61960206010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. proposed the idea. T.T., Y.W. and Y.Z. developed the theoretical description of the method. T.T., J.P., and Y.Z. conceived the experiments. T.T., J.L., and L.L. conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. T.T. and Y.Z. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, T., Zhang, Y., Wan, Y. et al. Dual frequency composite pattern temporal phase unwrapping for 3D surface measurement. Sci Rep 14, 24992 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76453-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76453-3