Abstract

Integrating sustainability values into decision-making processes is crucial for maximizing returns in residential construction projects while ensuring that project functions remain uncompromised. This study investigates the barriers to adopting drone technology in the construction industry, focusing on sustainable construction practices. This research identifies and analyzes key obstacles to drone implementation through an extensive literature review and a quantitative approach. Data were collected via a structured questionnaire administered to 147 professionals in the construction industry. The data were then analyzed using Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), revealing that regulatory barriers, including complex and varying legal frameworks, pose the most significant challenges to drone adoption. Additionally, concerns related to public perception, technical issues, and economic factors are identified as substantial hindrances. These findings underscore the necessity for policymakers and industry leaders to develop clear and consistent regulatory frameworks, promote industry-wide training programs, and address public and economic concerns to facilitate the broader adoption of drone technology in sustainable construction projects. The study’s insights contribute to the ongoing discourse on how emerging technologies can be effectively integrated into the construction sector to enhance sustainability and efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction industry is transforming significantly, embracing advanced technologies to enhance productivity, safety, and sustainability. Among these technologies, drones, or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), have emerged as powerful tools capable of performing a variety of tasks with unprecedented precision and efficiency1,2,3,4,5. Drones have proven valuable in construction activities such as site surveys, progress monitoring, safety inspections, and resource management. Their ability to capture high-resolution aerial imagery, generate accurate 3D models, and access hard-to-reach areas has positioned them as essential components in modern construction projects, particularly those that involve complex or large-scale sites6,7,8,9,10.

Despite the clear advantages of drone technology, its adoption within the construction industry has been slower than anticipated, especially in sustainable construction11,12,13,14,15. Sustainable construction, which emphasizes minimizing environmental impact, conserving resources, and enhancing energy efficiency, stands to benefit significantly from the precision and data-rich outputs provided by drones. For instance, drones can monitor environmental impacts, optimize material use, and reduce waste through more accurate planning and execution. These capabilities align directly with sustainable construction goals, which seek to balance economic, environmental, and social factors in infrastructure development16,17,18,19,20. However, the widespread implementation of drones in sustainable construction faces several barriers, including complex and evolving regulatory frameworks, technical limitations related to drone capabilities, public concerns regarding privacy and safety, and economic constraints such as the cost of acquisition and operation21,22,23,24,25.

The motivation for this study stems from the recognition that while the benefits of drones in construction are well-documented, there remains a significant gap in the literature concerning the specific barriers to their adoption in sustainable construction. Previous studies have focused on the technological advancements and operational efficiencies that drones bring to construction projects1,2,3,4,5. However, the challenges related to regulatory compliance, technical integration, and stakeholder acceptance, particularly in sustainable practices, have not been thoroughly addressed. This gap in understanding is critical because overcoming these barriers is essential for maximizing the potential of drones to contribute to sustainable construction efforts, which are increasingly recognized as vital for addressing global environmental challenges6,7,8,9,10.

Moreover, the urgency of adopting sustainable practices within the construction industry has never been greater, given the sector’s substantial contribution to global carbon emissions and resource consumption. As governments and industry leaders push for greener practices, integrating innovative technologies like drones becomes increasingly important11,12,13,14,15. Drones offer unique capabilities to enhance sustainability by providing detailed environmental data, improving resource management, and facilitating more efficient construction processes. However, realizing these benefits requires addressing the barriers that impede their broader adoption. These barriers include technical challenges and significant regulatory, social, and economic considerations that must be carefully navigated16,17,18,19,20.

This study aims to fill the research gap by systematically investigating the barriers to drone implementation in sustainable construction. Utilizing Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), this research analyzes data collected from professionals within the construction industry to identify the most significant obstacles and propose recommendations for overcoming them. This approach enables a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between these barriers, providing insights that are both theoretically robust and practically applicable21,22,23,24,25. The findings from this study are expected to contribute significantly to the ongoing discourse on the role of emerging technologies in shaping the construction industry’s future, particularly in the context of sustainability26,27,28,29,30.

Furthermore, the insights generated from this research are intended to support policymakers and industry leaders in developing strategies that promote drone technology adoption and enhance its effectiveness in achieving sustainability objectives. By addressing the regulatory, technical, social, and economic challenges associated with drone implementation, this study seeks to facilitate the broader adoption of drones, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and efficient construction practices worldwide26,27,28,29,30. In conclusion, this study seeks to identify and analyze the key barriers to drone implementation in sustainable construction and provides practical recommendations for overcoming these challenges. The findings are expected to support policymakers and industry leaders in developing strategies that facilitate the broader adoption of drone technology, ultimately contributing to the sustainability and efficiency of construction projects worldwide.

Drones implementation barriers

Even though drones were designed originally for army manoeuvres due to the risks and dangers for workers in operated warplanes, they now have many other applications. Besides delivering packages, drones are utilised in airborne monitoring and inspection of oil and gas pipelines and power lines1,2. Additionally, they are utilised in mapping, surveying and gathering geographic and spatial data. Drones have been implemented in construction and civil applications, healthcare, agriculture, security and public safety, imaging, mining, research and other scientific applications.

Drones are utilised for military operations, humanitarian aid, and data collection for quite a long time, longer than package delivery. There is successful surveying and mapping using drones3,4. Motion photogrammetry approaches have been employed to plot coral reefs using drones. The capacity and accuracy of drones have been demonstrated by equipping drones with high-definition video and photo cameras employed for the full graphic assessment and revealing damage concerning huge buildings, which is both cost-efficient and effective5,6.

The application of drones in farming was exhibited, and it recommended that drones be more effective than satellites since they are not blocked by clouds7,8. Drones are crucial in healthcare and medical deliveries, medication pick-ups, and patient test kits for patients with lingering illnesses. The drone could be a means for the global transplantation of organs in the future9,10. Drones play a central role in aid and relief tasks in calamitous circumstances. Thus, drones can be utilised for charitable aid during tragedies to assess destruction, detect survivors, and bring service. A company specialising in charitable aid through drones (Matternet) broadcast in January 2013 that it will employ drones to supply medication and other materials to isolated places in the Dominican Republic and Haiti11.

Many researchers have proposed approaches to tackle various concerns associated with drone delivery. Different advantages and disadvantages of drone delivery in urban centres have been outlined in the literature12,13,14. Likewise, a delivery system was proposed to respond to the restricted, transportable range of drones by serving customers while returning to a moving truck, signifying more efficiency of drone-truck arrangements. Additionally, the know-how behind drone delivery and the different components applied in making them, comprising batteries, motors and propellers, were extensively studied15,16. Similarly, a comparison was made between the drone-truck delivery system’s efficacy and that of a truck or standalone truck.

A vehicle routing problem(VRP) was developed to explicitly formulate drone deliveries as the current VRPs might not be relevant to drone carriage because of conditions such as several trips from a warehouse and the impact of payload capacity and battery limit17,18,19. There are studies on the challenges of cyber-physical security for drone carriage. Hence, a zero-sum game was established between the vendor making the drone carriage and an assailant attempting to interrupt the distribution via physical or cyber-attacks20,21. Models for drone carriage were subsequently proposed for healthcare services to enhance efficient, cost-effective and timely healthcare conveyance.

Conversely, drones have many limitations since they are UAVs and pose potential threats to the environment, nature, wildlife, properties and humans. Some of these limitations are related to secrecy, and drones have produced worries regarding the safety and privacy of individuals because they are presented to the community22,23. Another problem relates to the psychological anguish they can cause in some humans due to data security concerns. In some studies, the environmental impact of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions was discussed, and it was posited that when a buyer is far away from the warehouse, drones cause more emissions of CO2 than trucks24,25. These problems, as mentioned above, constitute barriers to successful drone implementation in the logistical industry.

Based on the existing literature, the focus was mainly on the issues concerning drone application at an operational or tactical level, e.g., routing, coverage of an area and operations search. Drone carriage is a new machinery. Therefore, it is pertinent to study the barriers to drone implementation in the construction industry to provide more insights to practitioners and researchers. The existing literature concerning the application of drone logistics in building engineering is lacking. Up-and-coming research on obstacle enquiry has been performed in various contexts, including sustainable development of renewable energy, implementation of blockchain, biorefineries development, computerised medical records in health care, and igniting a wind energy plant. This study employed the PLS-SEM approach to examine the barriers to drone implementation in the sustainable building business.

Many studies have used the PLS-SEM method to model many aspects of the building ruction business. For example, Bamgbade et al.26 assessed issues influencing sustainable construction employing PLS-SEM. The analysis discovered that the model results were reliable, and the pilot study data showed proof of rational validity. A PLS-SEM approach was employed as a mediation model for enhancing cost-effectiveness and its effects on smaller construction industries—the intervention effects of customer upkeep with early payment on cost performance issues. Results indicated three (3) factors that influence construction projects’ cost performance in emerging countries. These comprised cash flow difficulties, deceitful activities, and the impact of the type of building environment27.

Modelling response plans by the construction industry using PLS-SEM during COVID-19 indicated that project support and supply chain is needed to tackle the impacts related to materials, stability of the market and monetary aid are also needed to tackle project-related effects28. A PLS-SEM modelling of obstacles to viable building by Durdyev et al.29 revealed that effective and clear policy guidelines are critical for enforcing supply chain materials integration and practices in addition to financial inducements, eventually leading to the operative execution of SC creativities. Hence, efficient resource use and sustainable economic growth can be realised. Durdyev et al.30 proposed a construction client satisfaction model using the PLS-SEM approach. The study discovered that treating each client individually and showing a friendly approach concerning their needs will boost their satisfaction with their involvement with a contractor. Despite the availability of extensive literature, studies focusing on spotlighting barriers to drone implementation in construction projects are scarce. In this study, we attempt to narrow this gap and propose a PLS-SEM model to explore further the hurdles to drone application for the sustainable building business. The additional motivation guiding this study include:

-

The rapidly increasing interest among researchers and stakeholders in drone implementation,

-

The uncertainty of drone implementation in future, and.

-

The increasing acceptance of drones in society.

Barriers to drone implementation for sustainable construction

Based on the existing literature on drone implementation for sustainable construction, many different barriers were identified and summarized in Table 1, adopted from Sah et al.11. These barriers are further classified and discussed below. There is currently a scarcity of research focused on identifying the unique challenges and barriers to adopting drone technology in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry. While there is growing interest in utilizing drones for project efficiency, monitoring, and safety, the sector in Saudi Arabia has not yet fully explored the specific factors that impede adoption. Accordingly, these barriers were gathered from prior global research as indicated in Table 1 to investigate them within the Saudi Arabia domain.

Threat to privacy and security

Individuals panic about non-consensual footage by drones since they have cameras attached to them to aid with landing. Even though drones have been successfully utilised for operations, including border patrol, in the past, they hinder people’s freedom of assembly or expression57,58. Thus, drones will likely discourage people from participating in some events and associations because of panic about being recorded. Drone applications for construction activities have the prospect of being seen as mass data-gathering tools when they are performing construction activities within municipalities59,60. Therefore, it can be considered a violation of fundamental human rights. Hence, the data collection system’s transparency by drones has to be guaranteed so that society is aware of any gatherings in data collection and data sharing with people along construction sites.

Consequently, drones can undermine the security of construction sites if found in the wrong hands61,62. They are efficient physical and cyber-attacks by the society. Likewise, trick drones can masquerade themselves as project monitoring drones and transfer conned wireless signs that could steal project data, leading to property theft63,64. Communications from drone to drone produce a latent for spicy or rival companies, computer hackers and unfriendly countries to mark drone delivery schemes and cause crashes between drones and people or items65,66.

Regulations

Official rules and regulations comprise laws that regulate the way an industry operates. Rules and regulations associated with permission for drone operations in built-up areas are required as package delivery to buyers requires the drone to fly over the build-up areas, concerning an ancillary interval67,68. Even if the buyer offers permission for the drone to convey the product or survey construction site(s), the concern of people’s and other organisations’ permission might remain in the community. Hence, regulation is essential, and it is feasible only via intervention by the government. Rules concerning data gathering of video footage by drone distribution are also needed69,70. Drone implementation in construction can be a risk to civic confidentiality as it is challenging to measure the footage of project monitoring drones. Additionally, a concern relating to drone identity subsists since it is challenging to distinguish between private and organisational drones71,72. Thus, drone implementation for construction sustainability would be difficult until rules and regulations were established to address these concerns.

Public perception and psychological

Drones cause public anxiety concerning automation among people since they are unmanned, and the decisions are taken using a computer, which might be hypothetically susceptible to cyber-attacks73,74,75. Likewise, people have a view that drones are applicable only for military and surveillance uses, and thus, they do not want to be around the drone vicinity because of concern of being attacked or filmed22,76. Though drones for package delivery may not record without permission or attack, awareness concerning various drones and their functions must be made public. Likewise, people are concerned about ‘full Skies’ because many drones always hover over them. Additionally, due to the lack of drone limitations on roads like cars, society might not have an alternative to circumventing the ubiquitous drones77,78.

Construction monitoring by drones requires flying over communities, causing a threat to them42,79. Therefore, the expected large crowds of drones would cause concern among people affected by these drones. Similarly, communities may have misinterpretations regarding the tenacity of drones, considering them to be from an extremist from a hostile or a terrorist group or country. These perceptions might trigger fresh encounters or amplify the prevailing ones.

Environmental issues

Drones generate undesirable physiological effects on animals. It has been noticed that drones could affect flora and fauna. The extensive application of drones creates vivacious noise and shadows, which cause noise pollution and visual obstructions80,81,82. Likewise, drones’ GHG emissions were greater than trucks’ when the clients were no longer distant from warehouses.

Economic aspects

The construction industry generates job opportunities for different skilled and unskilled workers. However, as the industry implements drones in construction, many workers, including security personnel, are either shaded off or face pay reductions83,84. These concerns would impact the working class, causing increased job losses and widening the gap between the poor and rich. Globally, the cost of living keeps increasing at an unprecedented rate. Hence, this economic gap poses a huge liability for the world economy.

Technical issues

Drones face many mechanical (or practical) obstacles. These comprised strong winds, fog or rain85,86. Poor weather conditions might lead to drone crashing, eventually leading to property damage or physical injury and rising drone delivery risks87,88. The drone distribution threat is described as the possibility of the drone not working properly or being unable to convey the item, and it is a critical issue influencing drone implementation for sustainable construction. Therefore, drones must be vigorously supervised during their airlift to check for faults. It has been reported that drones have restricted battery life spans, which can be an issue if the client’s destination is not in the drone’s flight range. Likewise, the dearth of a hurdle to averting tools has been identified. Thus, drones must be able to escape birds, aircraft, structures, buildings and other drones. Lastly, drones have inadequate load volume, making conveying hefty items challenging during construction activities.

Gap analysis

Presently, the most important advantages of drones in the building business are associated with the computerisation of building activities, cost-effectiveness, good time management, safer real-time gathering of data compared with the conventional approaches, and reliable substitute over satellites and crewed aerial vehicles concerning high-resolution imageries89,90. However, regarding the application and wedged usage, there is a dearth of clarity and exemplification of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) in the building sector91,92. Hence, a literature review was performed to discover the potential gaps that might need to be addressed concerning the adoption of UAVs in the building business, the major barriers to circumstances and areas of application and justification. Vanderhorst et al.89 provided examples of models for contemporary application, such as disaster management and visualisation map development of the UAS based on the number of publications and phases of construction projects while applying the UAS. Similarly, Elghaish et al.93 critically reviewed digitisation with drones and immersive technologies in the building industry. The study has presented useful findings concerning the application of immersive and UAV tools, which can provide in-depth insight into the practical applications of these technologies in the construction business. The analysis was further underwritten to the desirable collective beginning for tracking evolution recorded in immersive and UAV know-hows and assessed their impacts on building schemes. However, this study opened a new horizon for new investigations concerning unexplored or partially explored aspects of digitised building projects, which is needed for in-depth insight into challenges/barriers to drone adoption. Hence, it will provide a basis for a roadmap to identify better what the business requires and offer guidance to experts and researchers assessing areas of application and obstacles that can have maximum paybacks for the building sector. Table 2 further summarises contributions made through studies on drone implementation and their current limitations or research gaps.

Based on this short review of studies on drone implementation in the construction industry, many areas needing further research have been identified. These include the need for more exploration concerning safety factors in the building industry, dearth of content analysis of the existing literature concerning hazard identification, lack of proper risk management by construction companies, lack of a multi-component toolkit for safety management, and neglect of continuous and direct physical human contact. Thus, there is a need to overcome technology implementation hurdles to address the low implementation of drone use in the construction industry. It will help narrow the knowledge gap concerning participants’ behavioural intention to apply to UAVs. In addition to further exploration of barriers to automation and adoption of robotics, this will help address the building engineering’s lack of comprehensive application of 4IR. Lastly, there is a need to address the challenges of initial costs, top management support and operation and maintenance support to improve processing and collection approaches of big spatial data, especially for larger building projects.

Research design and methods

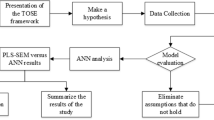

There is currently a scarcity of research addressing the challenges and barriers associated with the implementation of drone technology within the construction industry in Saudi Arabia. Despite the growing interest in utilizing drones for enhancing project efficiency, monitoring, and safety, the construction sector in the region has yet to fully explore and document the factors that hinder widespread adoption. Consequently, the barriers were compiled from prior global research addressing the challenges associated with drone implementation, as detailed in Table 1 to examine them within the context of Saudi Arabia. Accordingly, this research aims to boost the thoughtful, sustainable delivery of construction projects in Saudi Arabia by discovering and recognising the barriers to drone implementation. The phases of this study are modified from Othman et al.113, Buniya et al.114, Olanrewaju et al.115, and Kineber et al.116, as depicted in Fig. 1. The research design follows a systematic approach to investigate the implementation of drone technology in sustainable construction. The process begins with the identification of the research gap, which establishes the need for this study by highlighting the lack of comprehensive research on the barriers to drone adoption in sustainable construction.

Following this, the study identifies and examines the drones implementation barriers, which include various challenges and obstacles faced by the construction industry in adopting drone technology. To gather relevant data, a questionnaire survey was developed and administered to industry professionals with direct experience in construction and drone technology. This survey provided the primary data needed to explore these barriers in depth.

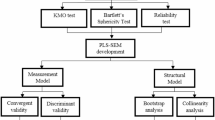

Subsequently, a PLS-SEM model was developed. This phase is divided into two key components:

-

Measurement Model: This assesses the validity and reliability of the constructs identified through EFA, ensuring that the data accurately reflects the underlying factors.

-

Structural Model: This component tests the hypothesized relationships between the constructs, allowing us to understand the direct and indirect effects of the identified barriers on the implementation of drones in sustainable construction.

The results of these analyses are then synthesized in the Results and Conclusions section, where the findings are discussed in relation to the study’s objectives. The ultimate goal of this research is to provide insights that contribute to the broader field of Sustainable Construction, offering recommendations for overcoming the barriers to drone implementation and supporting the integration of this technology into construction practices.

It is worth mentioning that the targeted participants are with relevant expertise in the construction industry of minimum five years of experience, including engineers, quantity surveyors, and architects. In addition, special contractors, operators, management experts, heavy-duty contractors, project executives, and staff directly involved in building projects were also included. To ensure a representative and informed sample, a stratified sampling method was employed, allowing us to specifically access subpopulations critical to this study, given the relatively new application of drone technology in Saudi Arabia136. This approach was carefully chosen to obtain the most precise and reliable results, reflecting the perspectives of those most knowledgeable about the challenges and potential of drone implementation in the construction sector. Using the commonly used Likert 5-point scale—“5” was extremely high, “4” was high, “3” was normal, “2” was low, and “1” was very low—respondents were given drone hurdles based on their knowledge and experience117,118. This has been accomplished in order to provide participants with a variety of responses that are based on prior building project experience. The sample size was based on the aim of the analysis119. A descriptive study, such as determining a normal distribution curve’s mean, mode, and median, would require more than thirty examples120. Yin121 suggested using a sample size greater than 100 for multivariate statistical analysis (e.g. PLS-SEM). On the other hand, Hair et al. (2016)135 recommended threshold is typically 100–150 respondents for models with medium complexity in PLS-SEM. Out of 200 building experts, 147 were approached in person (self-administered) and accepted for SEM analysis because this study used an SEM technique. They represented around 73% of the total response rate. For these kinds of investigations, this amount of return is deemed sufficient122,123. The individual approach and the extended period (100 days) allocated for data collecting were the reasons for the high response rate. Ethical approval was not required for this study, as per the policy of Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, which exempts studies using anonymous surveys without sensitive personal data or interventions from requiring formal ethical review.

Developing PLS-SEM model

The PLS-SEM model is widely used in various research fields, including social and management sciences, due to its flexibility and robustness in handling complex models with multiple constructs144. The method is particularly advantageous in situations where the research objective is predictive and the model involves formative constructs or smaller sample sizes, making it an ideal choice for exploratory studies like the present study. Different forms of research that employed the PLS-SEM method have been prominently featured in numerous high-impact journals, underscoring its credibility and widespread acceptance in the academic community145,146,147.

In this present study, SMART-PLS software (version 3.2.7) was employed to analyze the data and to model the relationships between the constructs using SEM. This software is well-suited for cloud computing and complex statistical modelling, allowing for a comprehensive examination of the hypothesized relationships. Initially, PLS-SEM was recommended for its robust predictive capabilities compared to covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM), particularly when the research model is complex and when the theory is less developed. Although CB-SEM has traditionally been favoured for theory testing, PLS-SEM has gained recognition for its ability to manage non-normal data and small to medium sample sizes effectively, with inconsistencies between the two approaches being comparatively low148.

In this study, the structural and measurement model assessments were integrated within the PLS-SEM analysis, ensuring a rigorous evaluation of both the reliability and validity of the constructs as well as the relationships between them. This dual approach is crucial for confirming the robustness of the model and for providing accurate predictions of the relationships under investigation. Adopting PLS-SEM ensured that the analysis was not only theoretically sound but also methodologically appropriate, given the nature and objectives of our research.

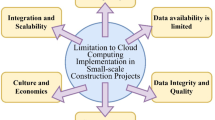

In this study, based on the extensive literature review in Sect. 2, six key barriers were identified as independent variables that influence the implementation of drone technology in the construction industry. These variables are critical to understanding the challenges faced by the industry in adopting this emerging technology and are categorized based on previous studies11. :

-

1.

Regulations: This variable encompasses the regulatory challenges that can impede drone adoption. Regulations may include legal restrictions, compliance requirements, and policy barriers that limit the use of drones in construction projects.

-

2.

Public Perception and Psychological Factors: This variable reflects societal acceptance and psychological barriers related to drone usage. Concerns about safety, privacy, and general apprehension about new technologies can affect the willingness of stakeholders to adopt drones.

-

3.

Environmental Issues: This variable highlights concerns regarding the environmental impact of drones. These may include potential negative effects on wildlife, noise pollution, and the carbon footprint associated with drone operations.

-

4.

Economic Aspects: This variable focuses on the financial challenges and costs associated with drone implementation. The cost of purchasing, maintaining, and operating drones can be a significant barrier for construction companies, particularly smaller firms.

-

5.

Technical Issues: This variable covers the technical limitations and challenges associated with drone technology. These challenges may include issues related to drone performance, reliability, data processing, and integration with existing construction processes.

-

6.

Threat to Privacy and Security: This variable represents concerns about privacy and security, which can hinder the acceptance and use of drones. The potential for drones to infringe on privacy, as well as security risks related to data breaches, are significant barriers that must be addressed.

The dependent variable in the model is Drones Implementation Barriers, which encapsulates the overall impact of these identified barriers on the successful adoption of drones in the construction sector. By analyzing the relationships between these independent variables and the dependent variable, this model provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors that need to be addressed to facilitate the widespread adoption of drone technology in construction.

Common method variance

The common method variance (CMV) is an inconsistency correspondence attributable to concepts and analytical tools applied124. Sometimes, individual data might exaggerate or predict the level of analysed connections and prompt challenges125,126. Hence, it is important for this study because all the analysed data is one-sided, personal and derived from a particular source. Likewise, it is important to consider these problems and identify any variation in the standard approach. Podsakoff and Organ127 explained a proper single-factor measurement derived from the factor analysis, representing a large variance percentage126. The measurement (or dimension model) indicates the correlations among variables and their latent concealed structure128. The convergent and discriminant validity of the model are discussed in the following sections:

Convergent validity

Convergent validity (CV) illustrates the extent of the covenant between two or more variables or tools of a comparable construct129. It is recognised as a subset of the construct validity. Regarding PLS, the estimated construct’s CV can be defined via three (3) tests130: Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Cronbach Alpha \(\:\left(\alpha\:\right)\) and Composite Reliability Scores (Pc). Nunnally and Bernstein (1978) also suggested a 0.7 Pc value and above for satisfactory composite reliability. In any analysis, 0.7 or above and 0.6 for empirical analysis are considered satisfactory131. The newest was the AVE, an archetypal tool used to evaluate the CV constructs in the measurement model. CV values above 0.5 are considered satisfactory131.

Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity (DV) suggests that the studied problem is procedurally distinct and describes that no measurement ascertains the singularity being assessed in SEM132. In contrast, Campbell and Fiske (1959) argued that the relationship between variables or different tools must be greater for DV to be performed.

Analytical model

This research aimed to discover and highlight drone adoption barriers via the SEM technique. The path coefficients among the computed coefficients should be recognised to obtain this. Hence, the fundamental correlation or path correlation was hypothesised between drones £ barriers and µ drone barriers. Thus, the underlying correlation among \(\:\text{\pounds\:},\:{\upmu\:}\:and\:\text{€}1\) rule in the analytical model is defined as inner correlation and might be illustrated as an undeviating equation133:

Where (β) represents the path coefficient connecting constructs of drone implementation barriers €1 represents the residual structural intensity variance likely to occur, and β is the consistent weight of regression, comparable to the β weight within multiple regression model. The emblems must be concurrent with the model estimates and analytically substantial. Regarding CFA, a bootstrapping technique built in the SMART-PLS 3.2.7 statistical package was employed to calculate the path coefficient’s standard error. This is conducted on 5000 sub-samples following Henseler et al. (2016), marking out the analysis of the statistical hypothesis. Four (4) structural equations regarding drone implementation construct barriers were also developed for the PLS model. It indicated the inner correlations of the constructs and Eq. 1.

Results and discussion

Demography of respondents

147 respondents participated in this study, all professionals within the construction industry. The demographic details of the respondents are summarized as follows:

-

Gender: The sample comprised 112 males (76%) and 35 females (24%).

-

Age: The respondents were categorized into four age groups: 20–30 years (25%), 31–40 years (40%), 41–50 years (20%), and above 50 years (15%).

-

Education Level: The educational qualifications of the respondents included Bachelor’s degrees (50%), Master’s degrees (35%), and PhDs (15%).

-

Professional Experience: The respondents had varying levels of professional experience in the construction industry: less than 5 years (20%), 5–10 years (35%), 11–20 years (30%), and more than 20 years (15%).

-

Job Roles: The participants held different positions within the construction sector, including engineers (40%), project managers (25%), architects (20%), quantity surveyors (10%), and other related roles (5%).

Common method variance

One-factor analysis was employed to assess the discrepancy in the standard procedure134. If the sum variance of the factor is below 50%, it indicates that the date was not influenced by the common method variance-CMV127. Likewise, the results indicated that the original components account for 42% of the total variance. Hence, it can be inferred that the CMV did not affect the findings because it is below 50%127.

Measurement model

The evaluation of the measurement model comprises estimating (i) average variance extracted (AVE), (ii) discriminant validity, and indicator reliability, as described by Hair Jr et al.135. The PLS algorithm was employed in this study after Wong131. Generally, indicators with outer loadings ranging from 0.4 to 0.7 must be tested for elimination from the scale, provided the indicator results lead to a substantial rise in composite reliability and AVE136. Those variables with 0.5 as outer loadings were classified as noncompliant with the standard and, as suggested, were eliminated from further analysis135. Therefore, it can be inferred that the level at which the indicator variance is approximately 50% was explained by its factor and the level at which the explained inconsistency is greater than the variance.

Figure 2 illustrates the initial structural equation model used to identify and analyze the barriers to drone implementation in the construction industry. This model represents the first iteration before modifications were made to remove indicators with low outer loadings. The constructs and their respective indicators are outlined. First, the “Regulations” construct represents the regulatory challenges associated with drone implementation. It is measured by six indicators (R1 to R6), with factor loadings ranging from 0.684 to 0.804. These loadings indicate the strength of each indicator in representing the regulatory barriers. Second, the “Public Perception and Psychological Factors” construct addresses societal and psychological challenges to drone adoption. It includes seven indicators (P1 to P7), though some indicators (P4, P5, and P6) show lower loadings, indicating weaker associations with the construct. The factor loadings for this construct range from 0.325 to 0.755. Third, the “Environmental Issues” construct addresses environmental concerns with four indicators (En1 to En4). The loadings range from 0.676 to 0.844, indicating a strong representation of environmental barriers by these indicators. Fourth, the “Economic Aspects” construct highlights the economic barriers to drone implementation. It is measured by five indicators (Ec1 to Ec5). While most indicators show high loadings (Ec2, Ec3, Ec4), indicating strong representation of economic barriers, a couple of indicators (Ec1, Ec5) have low loadings, suggesting weaker associations.

Fifth, the “Technical Issues” construct encompasses the technical challenges related to drone technology. It is measured by seven indicators (Te1 to Te7), with factor loadings ranging from 0.232 to 0.872. Most indicators show strong loadings, except for Te5, which indicates a weaker representation. Sixth, the “Threat to Privacy and Security” construct reflects concerns about privacy and security related to drone usage. It includes six indicators (T1 to T6), with loadings ranging from 0.561 to 0.844, showing a strong association of these factors with the construct. On the other hand, “Drones Implementation Barriers” is the central dependent variable, representing the overall barriers to drone implementation in the construction industry. The model shows that all the independent constructs (Regulations, Public Perception and Psychological Factors, Environmental Issues, Economic Aspects, Technical Issues, and Threat to Privacy and Security) contribute to this central construct. The factor loading for this construct is 1.000, indicating a perfect fit within the model.

As this is the initial model, it includes all proposed indicators, some of which exhibit low outer loadings. Indicators with particularly low loadings, such as P4, P5, P6, Ec1, Ec5, and Te5, were identified for potential removal in subsequent iterations of the model, as shown in Fig. 3. The process of refining the model by removing these low-loading indicators is crucial for improving the reliability and validity of the constructs, thereby enhancing the overall fit and explanatory power of the model.

Thus, the outer loadings from ec1, ec5, P6, p5, and p4 were removed from the original measurement model since meagre factor loadings were less than 0.5. Hence, it can be validated from their trivial effects on the related constructs. More so, a modified model was evaluated after eliminating the trivial constructs due to Cronbach Alpha limits. The sensitivity concerning internal consistency and convoluted variables was estimated concerning Composite Reliability (CR) following Hair Jr et al.135. In this type of analysis, cr values above 0.7 are considered suitable, as Hair Jr et al. (2016) indicated.

Similarly, CR values above 0.6 are considered satisfactory for exploratory analysis131. Based on this analysis, the model achieved a CR threshold value higher than 0.7, as indicated in Table 3, and thus, it is satisfactory. AVE is a distinctive technique for evaluating the convergent validity of model constructs with values above 0.5. Thus, it suggests a satisfactory convergent value concurrent with the existing literature131. As shown in Table 4, the results indicated that the entire model constructs passed the test. The findings, as contained in Table 4, revealed that all concepts of the model pass the test.

After obtaining a significant variation among the model constructs through the experiential standard, the discriminant validity (DV) will likely be outlined. Hence, establishing DV explains the peculiarities not defined properly by other model constructs137. The estimation of DV could be done in the following ways: i) Hetotrait-Monotrait Ration of Relationships (HTMT) and Fornell-Larcker’s (1981) Principle. The square root of the AVE of each construct was related to the correlations of an individual construct with the remaining constructs to evaluate the DV. The square root of DV has to be bigger than the correlations among the hidden constructs based on the criterion of Fornell and Larcker130. The results of this study have developed the analytical models’ DV, summarised in Table 5138.

Equally, many scientists have mastered the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion of normal DV. However, Henseler et al.139 recommended a distinct technique for DV estimation (i.e., HTMT). This is a new approach for DV estimation of variance-based SEMs and calculating what might be a precise correlation between the two variables (or constructs) that are estimated accurately, i.e., if the binary variables are measured consistently. Likewise, this study employed the HTMT model to assess the DV. Hair et al.132 contended that the HTMT values have to be less than 0.9 and 0.8. Thus, it implies that the binary constructs are different. Suppose the model constructs are comparable theoretically; the values of HTMT should be less than 9.0.

In contrast, if the HTMT values have to be less than 0.850, the model’s constructs must be different theoretically. The values of HTMT based on the analysed constructs are summarised in Table 3. Thus, the constructs have indicated satisfactory DV.

Verification path model

Once the drone technologies were demarcated as influential constructs, the collinearity amongst the formative construct’s variables might be assessed more by assessing the variable inflation factor (VIF). Likewise, the results indicated that all the values of VIF were less than 3.50. Hence, it suggested that these sub-constructs have independently supported the higher-order construct. In addition, the bootstrapping approach was used to predefine the effects of the path coefficients140. All paths were significant statistically at 0.01 level129. This is further exemplified in Figs. 2 and 3, and 4; Table 6.

Figure 4 illustrates the results of the bootstrapping analysis, showcasing the path coefficients between the identified barriers and the central construct, “Drones Implementation Barriers.” The path coefficients, along with their significance levels (p-values), are displayed on each arrow. The values indicate the strength and significance of the relationships, with all paths showing statistically significant connections (p < 0.05), thereby reinforcing the robustness of the model in explaining the barriers to drone adoption in the construction industry.

Discussion

This study employed Partial Least Square (PLS)-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS) and created a model for drone implementation barriers for sustainable building. The PLS-SEM modelling has been extensively used to study aspects of sustainable construction/ building concerning robotics, automation and drone technology. The PLS-SEM model established in this study offers valuable benefits concerning sustainable construction. Such results could increase understanding of barriers to drone implementation for sustainable construction. The PLS-SEM model discovered that regulations were the most important hurdle to DRONE application in construction. Several studies have reported similar results using the PLS-SEM approach141,142,143.

However, Aghimien et al.102 discovered that construction forms are still lagging concerning drone/UAV implementation, and most of the implementing firms are uncertain about using UAVs for their project delivery. In contrast to regulation, which is the major barrier to drone implementation, as revealed by this study, the study also revealed that the major factors affecting drone implementation in construction are: i) companies’ willingness to use drones. Others comprised effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence and facilitating circumstances. Hence, these factors that formed a barrier to drone implementation and supposed threat cannot be ignored since they have proven significant. Hence, addressing these barriers in addition to regulation could help narrow the existing gap in the literature by discovering the experts’ behavioural intention to implement drones for sustainable construction.

Notably, regulations and other drone implementation barriers exist in developed and developing countries144. These barriers are related to cost/economic factors that affect the development of drone implementation regarding the digitisation of the construction process in the built environment. Additionally, there are other critical barriers to drone implementation for sustainable construction. Onososen et al.144 further identified regulatory/technical factors as major barriers to drone implementation for sustainable construction. Therefore, the current results showed that addressing the regulations/rules concerning drone implementation could facilitate policy prescription to guide drone implementation for sustainable construction.

Current findings also concurred with those of Aiyetan and Das [170], who discovered that many factors and barriers under operational, economic, environmental, social-legal, and building-related aspects affect drone implementation. Conversely, five tactical dealings that comprised the formation of government policy objectives, rules and legal requirements, promoting competency building via piloting and training licences, authorising use of air space by drones for construction in and around project locations, cost analysis of drone and drone operations in the project budget and formation of company culture for implementing technological change can facilitate drone use in the building industry, particularly in emerging countries. Hence, it is essential to prepare for safe flight using drone protocols in the building industry145. Therefore, regulatory frameworks are required for standard cases of drone implementation for sustainable construction. Activities outside the regulatory frameworks must be properly appraised for regulation in the construction domain146. These regulations govern the capabilities and types of drones implemented for sustainable construction. The summary of findings and discussion is listed in Table 7 below.

Managerial and theoretical implications

Even though the idea of sustainable construction is not new147, it is clear that performance is a progressively essential function in different companies148. Thus, the suggested ranking procedure is a significant barrier to drone adoption, particularly for sustainable construction. The suggested model was used in this research to differentiate the barriers to drone implementation. Hence, the existing gap between drone implementation theory and practice has been narrowed by this research. Conversely, based on the available literature, there are limited research outputs regarding tackling drone implementation barriers by construction industries in Saudi Arabia. This study began by systematically analysing the key barriers to drone implementation that could assist drone use in the construction industry. Consequently, this inference has created a basis for future studies regarding the barriers to drone implementation by the construction industry in developing countries, especially regarding construction management aspects. The theoretical aspect of this research provided an analytical procedure for assessing the drone barriers that might be used successfully in Saudi Arabia and other emerging countries worldwide.

The six aspects of drone implementation barriers by the construction industry in Saudi Arabia were studied using the PLS-SEM technique. Thus, this study provided a framework for aiding new drone implementation stakeholders. Similarly, this study can have implications for the construction industry as follows:

It outlined the barriers to drone implementation and the related measurement to assess the importance of drone implantation and how those barriers can be tackled to expedite drone implementation. Findings could assist clients, consultants, and constructors in evaluating and eliminating the barriers to drone implementation and facilitate the accuracy of construction projects.

This study has illustrated a systematic proof that can assist developing nations in implementing drones in the construction industry by tackling the existing barriers. This scope of drone implementation has largely concentrated on developed nations. Hence, there is limited research output regarding drone adoption by construction industries in emerging nations, including Saudi Arabia. Therefore, this study has related drone implementation to Saudi Arabia’s construction sector by laying a strong basis for removing drone implementation barriers for sustainable construction of local projects.

The study developed a new PLS-SEM model, which upcoming studies can apply to assess drone implementation barriers by the construction industry. Hence, this model could be a game changer in construction projects. Although this study was conducted in Saudi Arabia, the suggested model will stimulate similar studies concerning drone implementation barriers worldwide. Current results also lay a foundation for knowledge goals regarding drone implementation, including cost-effectiveness and acceptable budget allocations to construction projects. Thus, key stakeholders can concentrate on the project goal concerning time, productivity and spending by developing and tracking the intended strategies. Thus, it could assist in achieving high standards and sustainability for construction projects. The summary of managerial and theoretical implications is listed in Table 8 below.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study has provided valuable insights into the challenges and potential of drone technology in enhancing the construction industry’s efficiency and sustainability, particularly within the context of Saudi Arabia. Through the application of the PLS-SEM approach, we developed a comprehensive model that identifies key barriers to drone adoption, including regulatory challenges, public perception issues, technical limitations, and economic constraints. Our findings underscore the viability of drones as a transformative tool in addressing the complexities of large-scale construction projects in developing nations, where such technology remains underutilized. The proposed model serves as a practical framework for construction stakeholders in Saudi Arabia, guiding them in overcoming these barriers to achieve better project outcomes, including cost reduction, time management, and improved project quality. However, given the unique regulatory, economic, and social environments of Saudi Arabia, these findings may not be directly applicable to other regions. Future research should focus on conducting similar studies in different geographical contexts to validate and refine the model, ensuring its broader applicability. Such comparative analyses could offer a deeper understanding of the global barriers to drone adoption in construction and support the development of tailored strategies that accommodate regional differences, ultimately promoting the widespread implementation of this promising technology.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Ahmed Osama Daoud, upon reasonable request.

References

Aminifar, F. & Rahmatian, F. Unmanned aerial vehicles in modern power systems: Technologies, use cases, outlooks, and challenges. IEEE Electrific. Mag. 8(4), 107–116 (2020).

Mohsan, S. A. H., Khan, M. A., Noor, F., Ullah, I. & Alsharif, M. H. Towards the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A comprehensive review. Drones 6(6), 147 (2022).

Euchi, J. Do drones have a realistic place in a pandemic fight for delivering medical supplies in healthcare systems problems? 182–190 (Elsevier, 2021).

Merkert, R. & Bushell, J. Managing the drone revolution: A systematic literature review into the current use of airborne drones and future strategic directions for their effective control. J. Air Transp. Manag. 89, 101929 (2020).

Feroz, S. & Abu Dabous, S. Uav-based remote sensing applications for bridge condition assessment. Remote Sens. 13(9), 1809 (2021).

Wang, J., & Ueda, T. Evaluation of the Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technology on Damage Inspection of Reinforced Concrete Buildings. in Proceedings of The 17th East Asian-Pacific Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction, 2022: EASEC-17, Singapore,: Springer, pp. 651–666 (2023).

Jafarbiglu, H. & Pourreza, A. A comprehensive review of remote sensing platforms, sensors, and applications in nut crops. Comput. Electron. Agric. 197, 106844 (2022).

Paul, K. et al. Viable smart sensors and their application in data driven agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 198, 107096 (2022).

De Silvestri, S., Capasso, P. J., Gargiulo, A., Molinari, S. & Sanna, A. Challenges for the routine application of drones in healthcare: A scoping review. Drones 7(12), 685 (2023).

Singh, K., Singh, P., & Angurala, M. Future Directions in Healthcare Research. in Computational Health Informatics for Biomedical Applications: Apple Academic Press, pp. 287–313. (2023)

Sah, B., Gupta, R. & Bani-Hani, D. Analysis of barriers to implement drone logistics. Int. J. Log. Res. Appl. 24(6), 531–550 (2021).

Kellermann, R., Biehle, T. & Fischer, L. Drones for parcel and passenger transportation: A literature review. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 4, 100088 (2020).

Benarbia, T. & Kyamakya, K. A literature review of drone-based package delivery logistics systems and their implementation feasibility. Sustainability 14(1), 360 (2021).

Thibbotuwawa, A., Bocewicz, G., Nielsen, P. & Banaszak, Z. Unmanned aerial vehicle routing problems: A literature review. Appl. Sci. 10(13), 4504 (2020).

Aabid, A. et al. Reviews on design and development of unmanned aerial vehicle (drone) for different applications. J. Mech. Eng. Res. Dev 45(2), 53–69 (2022).

Boukoberine, M. N., Zhou, Z. & Benbouzid, M. A critical review on unmanned aerial vehicles power supply and energy management: Solutions, strategies, and prospects. Appl. Energy 255, 113823 (2019).

Huang, S.-H., Huang, Y.-H., Blazquez, C. A. & Chen, C.-Y. Solving the vehicle routing problem with drone for delivery services using an ant colony optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Inf. 51, 101536 (2022).

Kitjacharoenchai, P. & Lee, S. Vehicle routing problem with drones for last mile delivery. Proc. Manuf. 39, 314–324 (2019).

Kuo, R., Lu, S.-H., Lai, P.-Y. & Mara, S. T. W. Vehicle routing problem with drones considering time windows. Expert Syst. Appl. 191, 116264 (2022).

Vamvakas, P., Tsiropoulou, E. E. & Papavassiliou, S. Exploiting prospect theory and risk-awareness to protect UAV-assisted network operation. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 1–20 (2019).

Ridwan, M. A., Radzi, N. A. M., Abdullah, F. & Jalil, Y. Applications of machine learning in networking: A survey of current issues and future challenges. IEEE Access 9, 52523–52556 (2021).

Yaacoub, J.-P., Noura, H., Salman, O. & Chehab, A. Security analysis of drones systems: Attacks, limitations, and recommendations. Internet of Things 11, 100218 (2020).

Rojas Viloria, D., Solano-Charris, E. L., Muñoz-Villamizar, A. & Montoya-Torres, J. R. Unmanned aerial vehicles/drones in vehicle routing problems: a literature review. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 28(4), 1626–1657 (2021).

Baldisseri, A., Siragusa, C., Seghezzi, A., Mangiaracina, R. & Tumino, A. Truck-based drone delivery system: An economic and environmental assessment. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 107, 103296 (2022).

Kirschstein, T. Comparison of energy demands of drone-based and ground-based parcel delivery services. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 78, 102209 (2020).

Bamgbade, J. A., Kamaruddeen, A. M. & Nawi, M. Factors influencing sustainable construction among construction firms in Malaysia: A preliminary study using PLS-SEM. Revista Tecnica De La Facultad De Ingenieria Universidad Del Zulia (Technical Journal of the Faculty of Engineering, TJFE) 38(3), 132–142 (2015).

Gambo, N., Said, I. & Ismail, R. Mediation model for improving cost factors that affect performance of small-scale building construction contract business in Nigeria: A PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Construct. Edu. Res. 13(1), 24–46 (2017).

Radzi, A. R., Rahman, R. A. & Almutairi, S. Modeling COVID-19 impacts and response strategies in the construction industry: PLS–SEM approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(9), 5326 (2022).

Durdyev, S., Ismail, S., Ihtiyar, A., Abu Bakar, N. F. S. & Darko, A. A partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) of barriers to sustainable construction in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 204, 564–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.304 (2018).

Durdyev, S., Ihtiyar, A., Banaitis, A. & Thurnell, D. The construction client satisfaction model: a PLS-SEM approach. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 24(1), 31–42 (2018).

Maharana, S. Commercial drones. in Proceedings of IRF International Conference, Mumbai, India, (2017).

Anbaroğlu, B. Parcel delivery in an urban environment using unmanned aerial systems: A vision paper. ISPRS Ann. Photogram., Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 4, 73–79 (2017).

Finn, R. L. & Wright, D. Unmanned aircraft systems: Surveillance, ethics and privacy in civil applications. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 28(2), 184–194 (2012).

Villasenor, J. “Drones” and the future of domestic aviation [Point of View]. Proc. IEEE 102(3), 235–238 (2014).

Solodov, A., Williams, A., Al Hanaei, S. & Goddard, B. Analyzing the threat of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) to nuclear facilities. Secur. J. 31, 305–324 (2018).

Naeem Akram R., et al. Security, Privacy and Safety Evaluation of Dynamic and Static Fleets of Drones. arXiv e-prints, p. arXiv: 1708.05732, 2017.

Chang, V., Chundury, P., & Chetty, M. Spiders in the sky: User perceptions of drones, privacy, and security. in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pp. 6765–6776 (2017).

Lidynia, C., Philipsen, R., & Ziefle, M. Droning on about drones—acceptance of and perceived barriers to drones in civil usage contexts. in Advances in Human Factors in Robots and Unmanned Systems: Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on Human Factors in Robots and Unmanned Systems, July 27–31, 2016, Walt Disney World®, Florida, USA: Springer, pp. 317–329 (2017).

Lords, H. O. Civilian Use of Drones in the EU. in Civilian Use of Drones in the EU. HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee 7th Report of Session 2014–15, (2015).

Dalamagkidis, K., Valavanis, K. P. & Piegl, L. A. On unmanned aircraft systems issues, challenges and operational restrictions preventing integration into the National Airspace System. Progr. Aerospace Sci. 44(7–8), 503–519 (2008).

Heutger, M., & Matthias, M. Unmanned aerial vehicle in logistics. ed: DHL, (2014).

Rao, B., Gopi, A. G. & Maione, R. The societal impact of commercial drones. Technol. Soc. 45, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2016.02.009 (2016).

Clothier, R. A., Greer, D. A., Greer, D. G. & Mehta, A. M. Risk perception and the public acceptance of drones. Risk analysis 35(6), 1167–1183 (2015).

Ravich, T. M. Commercial drones and the phantom menace. J. Int’l Media & Ent. L. 5, 175 (2013).

Duffy, R. Understanding the public perception of drones. ed, (2015).

Kwon, H., Kim, J. & Park, Y. Applying LSA text mining technique in envisioning social impacts of emerging technologies: The case of drone technology. Technovation 60, 15–28 (2017).

Bracken C. et al. Surveillance drones: Privacy implications of the spread of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in Canada. Surveillance Studies Centre: Queen’s University, Kingston, UK, vol. 30, (2014).

Goodchild, A. & Toy, J. Delivery by drone: An evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicle technology in reducing CO2 emissions in the delivery service industry. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 61, 58–67 (2018).

Clarke, R. & Moses, L. B. The regulation of civilian drones’ impacts on public safety. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 30(3), 263–285 (2014).

Sudbury, A. W. & Hutchinson, E. B. A cost analysis of amazon prime air (drone delivery). J. Econ. Educ. 16(1), 1–12 (2016).

Boucher, P. ‘You wouldn’t have your granny using them’: drawing boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable applications of civil drones. Sci. Eng. Ethics 22, 1391–1418 (2016).

Luehrs, A. How Drones Could Disrupt the Trucking Industry. https://www.trucks.com/2015/09/05/howdrones-could-disrupt-the-trucking-industry/," 2015: IEEE

Gupta, S. G., Ghonge, D. M., & Jawandhiya, P. M. Review of unmanned aircraft system (UAS). International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Engineering & Technology (IJARCET) Volume,2, 2013.

Parker, J. L., Johnson, C. M., Williams, E. O., Malik, J. P., & Foucha, N. M. Systems and methods for autonomous drone navigation," ed: Google Patents, 2018.

Hallermann, N., Morgenthal, G. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) for the assessment of existing structures. in IABSE Symposium Report, 2013, vol. 101, no. 14: International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering, pp. 1–8.

Yoo, W., Yu, E. & Jung, J. Drone delivery: Factors affecting the public’s attitude and intention to adopt. Telemat. Inf. 35(6), 1687–1700 (2018).

Yahuza, M. et al. Internet of drones security and privacy issues: Taxonomy and open challenges. IEEE Access 9, 57243–57270 (2021).

Ilgi, G. S., & Ever, Y. K. Critical analysis of security and privacy challenges for the Internet of drones: A survey. in Drones in smart-cities: Elsevier, 2020, pp. 207–214.

Hildmann, H. & Kovacs, E. Using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as mobile sensing platforms (MSPs) for disaster response, civil security and public safety. Drones 3(3), 59 (2019).

Sliusar, N., Filkin, T., Huber-Humer, M. & Ritzkowski, M. Drone technology in municipal solid waste management and landfilling: A comprehensive review. Waste Management 139, 1–16 (2022).

Khalid, M., Namian, M. & Massarra, C. The dark side of the drones: A review of emerging safety implications in construction. EPiC Seri. Built Environ. 2, 18–27 (2021).

Omolara, A. E., Alawida, M. & Abiodun, O. I. Drone cybersecurity issues, solutions, trend insights and future perspectives: A survey. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(31), 23063–23101 (2023).

Shrestha, R., Omidkar, A., Roudi, S. A., Abbas, R. & Kim, S. Machine-learning-enabled intrusion detection system for cellular connected UAV networks. Electronics 10(13), 1549 (2021).

Sayeed, M. A., Kumar, R. & Sharma, V. Safeguarding unmanned aerial systems: An approach for identifying malicious aerial nodes. IET Communications 14(17), 3000–3012 (2020).

Lavers, C. Design in Engineering: An Evaluation of Civilian and Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Platforms, Considering Smart Sensing with Ethical Design to Embody Mitigation Against Asymmetric Hostile Actor Exploitation 2021.

Chávez, K. & Swed, O. The proliferation of drones to violent nonstate actors. Defence Stud. 21(1), 1–24 (2021).

Janke, C. & de Haag, M. U. Implementation of European drone regulations-status quo and assessment. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 106(2), 33 (2022).

Tran, T.-H. & Nguyen, D.-D. Management and regulation of drone operation in urban environment: A case study. Soc. Sci. 11(10), 474 (2022).

Abdelmaboud, A. The internet of drones: Requirements, taxonomy, recent advances, and challenges of research trends. Sensors 21(17), 5718 (2021).

Labib, N. S., Brust, M. R., Danoy, G. & Bouvry, P. The rise of drones in internet of things: A survey on the evolution, prospects and challenges of unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Access 9, 115466–115487 (2021).

Sharma, M., Narwal, B., Anand, R., Mohapatra, A. K. & Yadav, R. PSECAS: A physical unclonable function based secure authentication scheme for Internet of Drones. Comput. Electr. Eng. 108, 108662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108662 (2023).

Srivastava, A. & Prakash, J. Future FANET with application and enabling techniques: Anatomization and sustainability issues. Computer Sci. Rev. 39, 100359 (2021).

Aydin, B. Public acceptance of drones: Knowledge, attitudes, and practice. Technol. Soc. 59, 101180 (2019).

Sabino, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the main factors for public acceptance of drones. Technol. Soc. 71, 102097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102097 (2022).

Sedig, K., Seaton, M. B., Drennan, I. R., Cheskes, S. & Dainty, K. N. Drones are a great idea! What is an AED?” novel insights from a qualitative study on public perception of using drones to deliver automatic external defibrillators. Resuscitation Plus 4, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2020.100033 (2020).

Adnan, W. H. & Khamis, M. F. Drone use in military and civilian application: Risk to national security. J. Media Inf. Warfare (JMIW) 15(1), 60–70 (2022).

Schulzke, M. Drone proliferation and the challenge of regulating dual-use technologies. Int. Stud. Rev. 21(3), 497–517 (2019).

Bine, L. M. S., Boukerche, A., Ruiz, L. B. & Loureiro, A. A. F. Connecting internet of drones and urban computing: methods, protocols and applications. Comput. Netw. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2023.110136 (2023).

Paneque-Gálvez, J., McCall, M. K., Napoletano, B. M., Wich, S. A. & Koh, L. P. Small drones for community-based forest monitoring: An assessment of their feasibility and potential in tropical areas. Forests 5(6), 1481–1507 (2014).

Gallacher, D. Drones to manage the urban environment: Risks, rewards, alternatives. J. Unmanned Vehicle Syst. 4(2), 115–124 (2016).

Watkins, S. et al. Ten questions concerning the use of drones in urban environments. Build. Environ. 167, 106458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106458 (2020).

Duffy, J. P. et al. Location, location, location: considerations when using lightweight drones in challenging environments. Remote Sens. Ecolo. and Conserv. 4(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.58 (2018).

Dorn, N. & Levi, M. European private security, corporate investigation and military services: collective security, market regulation and structuring the public sphere. Polic. Soc. 17(3), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460701497303 (2007).

Chordia, K., Bhagwatkar, D., Fernandes, D., Gill, A., & Jaju, A. To study the scope of drone usage for disaster management in India with respect to the USA with a comparison of economic factors including the GDP, the level of unemployment and inflation, and the government regulations 2022.

Mohsan, S. A. H., Othman, N. Q. H., Li, Y., Alsharif, M. H. & Khan, M. A. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): Practical aspects, applications, open challenges, security issues, and future trends. Intell. Serv. Robot. 16(1), 109–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11370-022-00452-4 (2023).

Bello, A. B. et al. Fixed-wing UAV flight operation under harsh weather conditions: A case study in Livingston Island Glaciers, Antarctica. Drones https://doi.org/10.3390/drones6120384 (2022).

Noca, F., Catry, G., Bosson, N., Bardazzi, L., Márquez, S., & Gros, A. Wind and weather facility for testing free-flying drones. in AIAA Aviation 2019 Forum, 2019, p. 2861.

Bärfuss, K. et al. Drone-based atmospheric soundings up to an altitude of 10 km-technical approach towards operations. Drones 6(12), 404 (2022).

Vanderhorst, H. R., Suresh, S., & Renukappa, S. Systematic literature research of the current implementation of unmanned aerial system (UAS) in the construction industry 2019.

Hatoum, M., & Nassereddine, H. The use of Drones in the construction industry: Applications and implementation. in ISARC. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, 2022, vol. 39: IAARC Publications, pp. 542–549.

Taylor, A. B. Counter-Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Study: Shipboard Laser Weapon System Engagement Strategies for Countering Drone Swarm Threats in the Maritime Environment," Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School, 2021.

Nelson, J. Policy Innovation for an Uncertain Future: Regulating Drone Use in Southern California Cities. Arizona State University, 2019.

Elghaish, F. et al. Toward digitalization in the construction industry with immersive and drones technologies: A critical literature review. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 10(3), 345–363 (2021).

Manzoor, B., Othman, I., Pomares, J. C. & Chong, H.-Y. A research framework of mitigating construction accidents in high-rise building projects via integrating building information modeling with emerging digital technologies. Appl. Sci. 11(18), 8359 (2021).

Vanderhorst, H. R., Suresh, S., Renukappa, S. & Heesom, D. Strategic framework of unmanned aerial systems integration in the disaster management public organisations of the Dominican Republic. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 56, 102088 (2021).

Siraj, N. B. & Fayek, A. R. Risk identification and common risks in construction: Literature review and content analysis. J. Construct. Eng. Manag. 145(9), 03119004 (2019).

El-Sayegh, S. M., Manjikian, S., Ibrahim, A., Abouelyousr, A. & Jabbour, R. Risk identification and assessment in sustainable construction projects in the UAE. J. Construct. Eng. Manag. 21(4), 327–336 (2021).

McSweeney, K. et al. Development of a comprehensive multi-component toolkit for offshore safety culture assessment. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 175, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.05.030 (2023).

Delgado Bellamy, D., Chance, G., Caleb-Solly, P. & Dogramadzi, S. Safety assessment review of a dressing assistance robot. Front. Robot. AI 8, 667316 (2021).

Nnaji, C. & Karakhan, A. A. Technologies for safety and health management in construction: Current use, implementation benefits and limitations, and adoption barriers. J. Build. Eng. 29, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101212 (2020).

Patrick, O. O., Nnadi, E. O. & Ajaelu, H. C. Effective use of quadcopter drones for safety and security monitoring in a building construction sites: Case study Enugu Metropolis Nigeria. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 12(1), 37–46 (2020).

Aghimien, D. et al. Empirical scrutiny of the behavioural intention of construction organisations to use unmanned aerial vehicles. Construct. Innov. 23(5), 1075–1094 (2023).

Balasubramanian, S., Shukla, V., Islam, N., Manghat, S. Construction industry 4.0 and sustainability: An enabling framework. IEEE transactions on engineering management, 2021.

Law, C. H. Y. "Drone technology and its implications to the Malaysian construction industry," UTAR, 2021.

York, D. D., Al-Bayati, A. J. & Al-Shabbani, Z. Y. Potential applications of UAV within the construction industry and the challenges limiting implementation. In Construction Research Congress 2020 31–39 (American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, 2020).

Almalki, F. A., Soufiene, B. O., Alsamhi, S. H. & Sakli, H. A low-cost platform for environmental smart farming monitoring system based on IoT and UAVs. Sustainability 13(11), 5908 (2021).

Alsamhi, S. H. et al. Blockchain-empowered security and energy efficiency of drone swarm consensus for environment exploration. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 7(1), 328–338 (2022).

Saif, A. et al. Distributed clustering for user devices under UAV coverage area during disaster recovery. in 2021 IEEE International Conference in Power Engineering Application (ICPEA), 2021: IEEE, pp. 143–148.

Aiyetan, A. & Das, D. Use of Drones for construction in developing countries: Barriers and strategic interventions. Int. J. Construct. Manag. 23(16), 2888–2897 (2023).

Liang, H., Lee, S.-C., Bae, W., Kim, J. & Seo, S. Towards UAVs in construction: advancements, challenges, and future directions for monitoring and inspection. Drones 7(3), 202 (2023).

Yahya, M. Y., Shun, W. P., Yassin, A. M. & Omar, R. The Challenges of Drone Application in the Construction Industry. J. Technol. Manag. Bu. 8(1), 20–27 (2021).

F. Dejonghe, "Drone technology readiness and adoption in the construction and surveying industry," ed: Ghent University. 2019.

Othman, I., Kineber, A., Oke, A., Zayed, T., & Buniya, M. Barriers of value management implementation for building projects in Egyptian construction industry. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2020.

Buniya, M. K., Othman, I., Sunindijo, R. Y., Kineber, A. F., Mussi, E., & Ahmad, H. Barriers to safety program implementation in the construction industry. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2020.

Olanrewaju, O. I., Kineber, A. F., Chileshe, N. & Edwards, D. J. Modelling the Impact of Building Information Modelling (BIM) Implementation Drivers and Awareness on Project Lifecycle. Sustainability 13(16), 8887 (2021).

Kineber, A. F., Othman, I., Oke, A. E., Chileshe, N. & Zayed, T. Exploring the value management critical success factors for sustainable residential building – A structural equation modelling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 293, 126115 (2021).

A. M. Al-Yami, "An integrated approach to value management and sustainable construction during strategic briefing in Saudi construction projects," © Ali Al-Yami, 2008.

Lai, N. K. Value management in construction industry (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 2006).

A. Badewi, "Investigating benefits realisation process for enterprise resource planning systems," 2016.

A. Field, Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. sage, 2013.

R. K. Yin, "Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th edn., vol. 5," Applied social research methods series, 2009.

C. Kothari, "Research Methodology Methods and Techniques 2 nd Revised edition New Age International publishers," Retrieved February, vol. 20, p. 2018, 2009.

Wahyuni, D. The research design maze: Understanding paradigms, cases, methods and methodologies. J. Appl. Manag. Account. Res. 10(1), 69–80 (2012).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879 (2003).

Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A. & Buckley, M. R. Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: reality or artifact?. J. Appl. Psychol. 74(3), 462 (1989).

Strandholm, K., Kumar, K. & Subramanian, R. Examining the interrelationships among perceived environmental change, strategic response, managerial characteristics, and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 57(1), 58–68 (2004).

Podsakoff, P. M. & Organ, D. W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12(4), 531–544 (1986).