Abstract

The formation of the topological surface state originates from bulk band inversion at the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band. The transition between normal and topological insulators is known as a topological phase transition. Here we show spin-polarized electronic states of Pb-based ternary topological insulators Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 (x = 0.55, 0.70, 0.79) investigated by spin- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy and first-principles calculations. We visualize a pair of spin-polarized surface resonances dispersing along the upper edge of projected bulk bands in occupied states. Interestingly, a branch of the spin-polarized surface resonances continuously connects to the topological surface state. The coexistence of the topological surface state and the spin-polarized surface resonances can be explained by considering the topological phase transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent progress in science and technology based on spin-polarized electrons in solid surfaces/interfaces is remarkable. To develop novel functions, it is essential to utilize the spin-polarized electrons and control them by engineering techniques. In this context, a topological surface state (TSS) holds enormous potential because of prohibited spin-dependent backscattering. Tuning the band bending in the topological insulator is one of the useful routes to control the spin-polarized electrons and pure spin currents1,2. Another distinct way is to utilize the topological phase transition. The formation mechanism of TSS is well established theoretically3,4,5,6, where the bulk band inversion with different parities between the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band is required. The phase transition from a trivial insulator to a topological insulator due to the bulk band inversion is known as the topological phase transition. Accordingly, elucidating the modification of electronic states driven by the topological phase transition is not only of interest as fundamental research but is also crucial in technological aspects, such as topological electronics, photonics, and thermoelectrics7,8,9,10.

The evolution of the TSS due to the topological phase transition has been demonstrated in several systems, where the bulk band inversion is artificially controlled by changing the composition11,12,13,14,15, varying the film thickness16,17, and modulating the lattice constant by strain 18,19. The spin-polarized electronic states for pristine topological materials can also be understood by considering topological phase transition. For instance, Jozwiak et al. found spin-polarized trivial unoccupied surface resonances accompanied by the TSS in a prototypical topological insulator, Bi2Se3, and concluded that the topological phase transition resulted in the coevolution of the TSS and the spin-polarized unoccupied surface resonances 20. Here, we point out that the coexistence of the spin-polarized surface resonance and the TSS reflecting the topological phase transition can also exist in the occupied state. The rich variety of spin-polarized surface states near the Fermi level is crucial for spintronic applications.

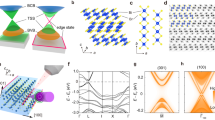

Pb-based ternary compounds, Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4, have been theoretically and experimentally revealed to be topological insulators21,22,23,24,25,26. The emergence of the TSS of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 originates from the bulk band inversion at the Z point in a three-dimensional bulk Brillouin zone21. Thus, the (111) surface possesses the TSS at \(\bar{\Gamma}\) point in the surface Brillouin zone [Fig. 1(a)]. In the previous ARPES studies, the TSS above a Dirac point (DP) has been investigated intensively24,25. In contrast, the dispersive feature below the DP is unclear. This might be caused by the bulk electronic states in the vicinity of the surface states, making it difficult to identify the dispersion shape of the surface states. The investigation of the spin-polarized electronic states around the TSS can provide deep insight into the formation mechanism of the TSS. In addition, the spin texture of the bands around the DP is significant in band engineering using topological materials.

Electronic band structures for Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 (x = 0.55, 0.70, 0.79). (a) Bulk Brillouin zone and (111) surface Brillouin zone. (b−d) ARPES intensity images along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) for x = 0.55, 0.70, 0.79, respectively. Dashed curves represent the projected bulk band edges determined from the calculated bulk bands shown in Fig. 3(a). (e) Constant energy contours of the ARPES intensity x = 0.70 recorded with h ν= 6.994 eV photons.

In this article, we perform a systematic study of the spin-polarized surface-derived states of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 (x = 0.55, 0.70, 0.79), investigated by spin- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy with a laser (laser-SARPES)27. We reveal several spin-polarized surface resonances in addition to the TSS. Interestingly, a branch of the occupied spin-split surface resonances continuously connects to the TSS. Theoretical calculations also show the spin-polarized surface resonance accompanying the TSS. The coexistence of the TSS and the adjacent surface resonance with opposite spin helicity is explained by the topological phase transition from a trivial insulator with Rashba-type spin-polarized surface bands. Appropriate tuning of the Fermi level is essential to control the performance of the material since the oppositely spin-polarized surface resonance near the TSS significantly affects material properties.

Results

Figures 1(b)−(d) show the ARPES intensity maps for x = 0.55, 0.70 and 0.79 recorded along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\), respectively. The bulk valence (conduction) band maximum (minimum) is identified from the calculated bulk bands. We note that the shape of the projected bulk band edge is based on the calculation results of PbSb2Te4 (i.e., x = 1.0) [Supplementary Fig. S1]. According to the previous theoretical study, the wavenumber and energy of the valence band maximum (VBM) depend on x, where the VBM for x = 0.0 is located at a wave number |k|~ 0.3 Å−1 in the \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) axis at the binding energy comparable to that of the DP, whereas the VBM for x = 1.0 is located at \(\bar{\Gamma}\) at the energy of 40 meV below the DP 23. Thus, the actual bulk valence band edges around |k|~ 0.3 Å−1 for x = 0.55, 0.70, and 0.79 are found in the lower binding energy side slightly.

Dispersive features of the TSSs around \(\bar{\Gamma}\) are similar to reported band structures for PbBi2Te4 (i.e., x = 0.0) in the previous ARPES studies except for the band energy because of the difference in composition ratio24,25. Here, we point out that the precise band structure near the DP has been demonstrated in the present study thanks to our high-resolution laser-ARPES. For x = 0.55 (x = 0.70), we find the TSS with the Fermi wavenumbers of ± 0.13 Å-1 (± 0.10 Å−1). The DPs for x = 0.55 and 0.70 are observed at the binding energies EB = 280 meV and 190 meV, respectively, meaning that the Dirac carriers for x = 0.55 and 0.70 are n-type. Meanwhile, the bands for x = 0.79 are shifted to 0.2 eV lower binding energy side than those for x = 0.70. Thus, the DP for x = 0.79 is located above the Fermi level, meaning that the Dirac carriers for x = 0.79 are p-type. The energy shifts of the bands upon changing the composition of Bi and Sb agree with the results reported in reference24.

The TSSs merge into the projected bulk valence bands around |k|~ 0.1 Å−1, indicating that the surface states change to surface resonances. Hereafter, we call these states lower surface resonances (LSRs). The LSRs for x = 0.55, x = 0.70, and x = 0.79 disperse in the binding energy range of 0.4–0.6 eV, 0.3–0.5 eV, and 0.1–0.3 eV, respectively. The spectral widths of the LSRs are broadened compared with those of pure surface states in the band gap. The photoemission intensities from the pure surface states are prominent, while those from the surface resonances are weakened drastically. One can find electron pockets in conduction bands located inside the TSSs with an energy minimum of 180 meV above the DP. A similar two-dimensional state in the conduction band for x = 0.0 has been observed in the previous ARPES study25. Our DFT calculation (shown later) suggests that the corresponding bands disperse along the upper edges of the projected bulk conduction bands. Therefore, we attribute these electron pockets in the conduction bands to upper surface resonances (USRs). We note that spin resolution plays an important role in identifying the dispersive features of the bands.

Figure 1(e) shows constant energy contours for x = 0.70. The photoelectron intensity distribution is symmetric (asymmetric) in the direction perpendicular (parallel) to the mirror plane with respect to ky = 0 (kx = 0), which reflects the experimental geometry in the photoemission process. On the lower binding energy side above the DP, the constant energy contours gradually change from circular to hexagonal shapes with decreasing the binding energy: the constant energy contours at EB = 110 meV and 150 meV are circular, at EB = 70 meV, a single hexagon, and at EB = 30 meV the USR appears at \(\bar{\Gamma}\) in addition to the hexagonal TSS. On the other hand, the constant energy contours on the higher binding energy side below the DP show a strong warping effect. The constant energy contours at EB = 260 meV and 330 meV are elongated in \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) while they are significantly curved inward in \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{K}}\).

Figures 2(a) and (b) display SARPES images for x = 0.55 and 0.70 recorded along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) with a p-polarized light. The spin polarization of the TSS is inverted with respect to \(\bar{\Gamma}\), resulting in a spin-helical texture. More interestingly, the spin polarization in the opposite direction to the TSS is observed in the wavenumber region |k|~ 0.08 – 0.18 Å-1 below the DP. It will be shown later that this is due to the existence of another band. Furthermore, we find the spin polarization of the USR in the conduction band, which is also inverted with respect to \(\bar{\Gamma}\) [Figs. 2(a), (c)]. The precise analysis of momentum distribution curves (MDCs) reveals that the spin degeneracy of the USR is lifted [Fig. 2(d)], resulting in the Rashba-like spin splitting. Here, the photoelectron intensities from inner spin-polarized branches are prominent compared with those from outer spin-polarized branches. We also note that the photoelectron intensity from the TSS in the negative wavenumber side is rather weak. The modulations of the photoelectron intensities are due to the matrix element effect in photoemission.

Spin-resolved band structures for x = 0.55, 0.70, 0.79. (a, b) SARPES images recorded with the p-polarized light along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) for x = 0.55, 0.70, respectively. The color scale displays both spin polarization and photoemission intensity. (c) An enlarged SARPES image and (d) the MDCs for x = 0.55 at 20, 40, 60 meV. Each MDC is obtained by summing the photoemission intensity within an energy window of 20 meV. Symbols in (d) represent the peak positions of MDCs for the guide to the eye. (e) A SARPES image for x = 0. 79 along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\). (f) EDCs obtained from (e) at the photoelectron emission angles of \(\theta_{e}\) . Symbols represent the peak positions. (g) Schematic drawing of the band structure of the TSS and the spin-polarized surface resonances.

To obtain a whole picture of the spin-polarized bands in the valence band around \(\bar{\Gamma}\), we have performed SARPES measurements for x = 0.79 over wide ranges of both the energy and momentum [Fig. 2(e)]. As the ARPES result shown in Fig. 1(d), the DP for x = 0.79 is located above the Fermi level. The spin-polarized LSRs disperse downward from the Fermi level near \(\bar{\Gamma}\) and lie around EB = 0.2–0.3 eV. In addition, surprisingly, the spin polarization is observed even outside of the bulk band gap region away from \(\bar{\Gamma}\), |k|> 0.2 Å-1 at least. According to the previous theoretical calculations25, the parity inversion of the bulk bands occurs in the wavenumber range of about ± 0.1 Å-1. Therefore, the topological origin cannot explain the spin polarization at the high k points. Furthermore, the spin-polarized bands that are inverted with respect to \(\bar{\Gamma}\) are found on the higher binding energy side EB = 0.5–0.8 eV and are also attributed to the surface-derived states.

The spin-resolved energy distribution curves (EDCs) provide precise information about the dispersive feature of the LSRs [Fig. 2(f)], and reveal the existence of a spin-split pair of the LSRs. The upper branch of the LSRs has the same spin orientation as the TSS and is continuously connected to the TSS. The lower branch with the spin polarization opposite to the TSS appears around |k|~ 0.1–0.2 Å-1 with peak positions of EB = 0.2–0.3 eV. The energy difference between the upper and lower branches is estimated to be 100 meV. We note that the photoemission intensity from the lower branch is much higher than that from the upper one. Therefore, we conclude that the TSS switches to the LSRs away from \(\bar{\Gamma}\), where the upper branch of the LSRs continuously connects to the TSS while the lower branch merges into the bulk states near \(\bar{\Gamma}\). We notice here that the wavenumber at which the TSS changes to the spin-split surface resonances roughly corresponds to the wavenumber at which bulk band inversion occurs 25. We represent the schematic drawing of the surface resonances and the TSS in Fig. 2(g).

In our DFT calculations, we start by examining which of the theoretical bands, PbBi2Te4 (x = 0.0) or PbSb2Te4 (x = 1.0), is more likely to reproduce the experimental results (Fig. S1). From the comparison of the calculated band structures, we find that the TSSs and the surface resonances appear for both x = 0.0 and x = 1.0 around \(\bar{\Gamma}\). In contrast, the wavenumber positions of the valence band maxima are different. Eventually, we judged that the calculations for x = 1.0 more closely reproduce the experimental results [Fig. 3(a)].

Calculated band structures. DFT calculations for PbSb2Te4 (x = 1.0) along \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) over the wide region (a) and focused around the TSS (b), respectively. The red (blue) circles represent the spin polarization in the + y (−y) direction. The red-white-blue color of the circles is proportional to the absolute value of the net spin polarization. The size of the circles is proportional to the net contribution from the total orbitals of Pb, Sb, and Te in three septuple layers from the surface. The shaded area represents the projected bulk bands.

In addition to the spin-polarized TSSs in the fundamental gap, spin-polarized surface-derived states are found in the first local gap between the first and second bulk valence bands, which agrees with the SARPES results shown in Fig. 2(e). Besides, X-shaped spin-polarized states also appear in the second local band gap at the energy of 1.2 eV. These surface-derived states might also be non-trivial, suggesting the coexistence of multiple topological states in this material. The existence of the TSSs in the local gaps has been suggested in the previous theoretical study 28,29. More recently, the multiple TSSs have been demonstrated in iron-based superconductors 30. It is intriguing to note that the spin textures in the first and second local gaps are the same as the TSS in the fundamental gap, while the third local gap is reversed.

Next, we focus on the band structure near the Fermi level around \(\bar{\Gamma}\) [Fig. 3(b)]. The pair of the spin-polarized LSRs exists just below the DP. The upper branch of the LSRs is continuously connected to the TSS. The lower branch of the LSRs merges into the bulk electronic states in the close vicinity of \(\bar{\Gamma}\). In contrast, the contribution from the surface increases away from \(\bar{\Gamma}\). Besides, the spin polarization of the lower branch is rapidly diminishing away from \(\bar{\Gamma}\). This feature agrees with the SARPES results shown in Fig. 2, where the lower branch of the LSRs emerges only in the wavenumber range of 0.08–0.18 Å-1. Above the DP, the TSS merges into the bulk bands around EB ~−0.2 eV. The Rashba-like spin-polarized surface resonances, corresponding to the USRs, appear along the upper edge of the first bulk conduction bands around \(\bar{\Gamma}\), corresponding to the USRs, appear along the upper edge of the first bulk conduction bands around \(\bar{\Gamma}\).

Discussion

The spin-polarized band structure near the top of the valence band for Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 can be understood phenomenologically by considering the topological phase transition from the normal insulator to the topological insulator by increasing spin-orbit coupling (SOC). In the normal insulator phase, the truncation of the bulk Bloch states at the surface forms the surface resonance along the upper edge of the bulk valence bands [Fig. 4(a)]. This state exhibits a two-dimensional nature, partially retaining the character of the bulk electronic states. The surface state formed with this mechanism is known as a Shockley state31. Besides, the surface resonance in the normal insulator phase is capable of the Rashba spin splitting due to the SOC. Subsequently, the touching between the bulk valence and conduction bands results in a gapless Dirac semimetal phase [Fig. 4(b)], where the SOC induces the energy modulation of the bulk bands. Further increase of the SOC results in the bulk band inversion near \(\bar{\Gamma}\) [Fig. 4(c)]. At this stage, one branch of the surface resonances evolves into the TSS. Therefore, the coexistence of the spin-polarized surface resonance connected to the TSS and adjacent surface resonance with opposite spin helicity indicates that the system has hypothetically undergone the topological phase transition. Here, we point out that the trivial spin-polarized surface resonances are found in various systems32,33,34,35. In this context, the formation of the surface resonance is general, while the evolution into the TSS requiring band inversion is additional.

The spin-polarized surface resonances accompanied by the TSS have been reported in the unoccupied states of Bi2Se320. In the case of Bi2Se3, giant Rashba spin-split surface resonances across the first bulk conduction bands are assumed even in the trivial insulator phase, of which a lower branch evolves into the TSS resulting from the topological phase transition. In contrast, we demonstrate that the spin-split surface resonances along the upper edge of the projected bulk valence bands evolve into the TSSs. Importantly, the surface resonances along the upper edge of the bulk conduction bands are not involved in the topological phase transition. In addition, in our scenario, we can start from the tiny spin-split band model in the trivial insulator phase, which is reasonable because the size of the spin splitting should be small in this phase. Thus, the formation mechanism of the TSSs for Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 is qualitatively different from that for Bi2Se3. In fact, a similar model is theoretically proposed in the Supplementary Fig. 6 of reference20 as another possible case of the topological phase transition.

One of the surprising results in the present study is the existence of the surface resonances with opposite spins adjacent to the TSS. This means that the spin polarization of the conducting electrons changes with electron filling. In Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4, only the spin-helical TSS exists above the DP, allowing manipulation of highly spin-polarized electrons. Below the DP, in contrast, the polarization of the spin current is largely reduced due to the LSR with the opposite spin to the TSS. The coexistence of the TSS and the adjacent surface resonance with opposite spin helicity is a general consequence that the system undergoes the topological phase transition. Therefore, the oppositely spin-polarized surface-derived states near the TSSs are possible in other topological insulators and, thus, considerably affect the material properties. It is essential to optimize the performance of the materials and devices by considering the existence of the adjacent band with the opposite spin to the TSS when applied to spintronics.

Methods

Sample preparation methods

Single phase samples of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 were synthesized by vertical Bridgman method36. A stoichiometric mixture of high-purity (6N) elements was first sealed into an evacuated conical-bottom quartz ampoule. The mixture was first melted at 800 ºC and was shaken in a furnace, followed by air cooling. Afterward, the mixture was placed in a Bridgman furnace and was melted at 800 ºC for 24 h. The melt was then cooled down at a rate of approximately 6 ºC/h down to 200 ºC. The grown crystals were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction and an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA). Single-phased Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 was obtained in the middle part of the ingot, while PbTe and (Bi,Sb)2Te3 impurity phases were included at the initial and end stages of the crystallization process, respectively. From EPMA analyses, the Bi:Sb ratio in Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 single phase region was almost identical to the nominal composition, except a slight concentration gradient of Δx = 0.01 along the growth direction with higher Sb concentration at the end stage of crystallization.

ARPES and SARPES

ARPES and SARPES have been performed at the Institute for Solid State Physics, The University of Tokyo27. The samples were cleaved with scotch tape in an ultra-high vacuum chamber below the base pressure of 1.0 × 10–8 Pa. We used a 6.994-eV laser as a light source for photoemission 37. The photoelectrons were analyzed by a ScientaOmicron DA30L analyzer and the spin information was obtained by the very-low-energy-electron-diffraction-type spin detector. The light incident plane was parallel to the \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) mirror plane of the sample. We used a p-polarized light, for which the electric-field vector is parallel to the light incident plane. The spin polarization perpendicular to the \(\bar{\Gamma}\bar{\rm{M}}\) mirror plane was detected in SARPES38. The ARPES and SARPES spectra were recorded with 5 and 10 meV instrument energy resolutions, respectively. The sample temperature was set to be 35 K during the measurements.

DFT calculations

The DFT calculations were performed using the OpenMX code, which is based on the norm-conserving relativistic pseudopotentials and optimized pseudo-atomic basis functions39,40. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof form was employed for exchange–correlation energy41. The basis functions of s3p2d2f1 were allocated for each atom, and the cutoff radius was chosen to be 7.0, 7.0, and 8.0 Bohr for Te, Sb, and Pb, respectively. The crystal structure of the bulk PbSb2Te4 was obtained by geometrical optimization without the SOC until the force on each atom was relaxed to be less than 1 × 10–5 Hartree/Bohr. We used a 12 × 12 × 3 k-point mesh and an energy cutoff of 300 Ry for this calculation. Then, we constructed a slab model consisting of five bulk unit cells and a vacuum layer of 3.0 nm and carried out noncolinear calculations with the SOC turned on. A 9 × 9 × 1 k-point mesh and an energy cutoff of 300 Ry were used. The spin texture and the contribution from each atom were analyzed using the kSpin code distributed with the OpenMX package42.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hsieh, D. et al. A tunable topological insulator in the spin helical Dirac transport regime. Nature 460, 1101–1105 (2009).

ViolBarbosa, C. E. et al. Direct observation of band bending in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 88, 195128 (2013).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys Rev B 76, 045302 (2007).

Fu, L., Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Topological Insulators in Three Dimensions. Phys Rev Lett 98, 106803 (2007).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium : Topological insulators. Rev Mod Phys 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev Mod Phys 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Tokura, Y., Kawasaki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Emergent functions of quantum materials. Nat Phys 13, 1056–1068 (2017).

Gilbert, M. J. Topological electronics. Commun Phys 4, 70 (2021).

Politano, A., Viti, L. & Vitiello, M. S. Optoelectronic devices, plasmonics, and photonics with topological insulators. APL Mater 5, 035504 (2017).

Chen, L.-C. et al. Enhancement of thermoelectric performance across the topological phase transition in dense lead selenide. Nat Mater 18, 1321–1326 (2019).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Topological phase transition and texture inversion in a tunable topological insulator. Science 1979(332), 560–564 (2011).

Brahlek, M. et al. Topological-metal to band-insulator transition in (Bi1−xInx)2Se3 thin films. Phys Rev Lett 109, 186403 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Topology-driven magnetic quantum phase transition in topological insulators. Science 1979(339), 1582–1586 (2013).

Wu, L. et al. A sudden collapse in the transport lifetime across the topological phase transition in (Bi1−xInx)2Se3. Nat Phys 9, 410–414 (2013).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Unconventional transformation of spin Dirac phase across a topological quantum phase transition. Nat Commun 6, 6870 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Crossover of the three-dimensional topological insulator Bi2Se3 to the two-dimensional limit. Nat Phys 6, 584–588 (2010).

Chen, K. H. M. et al. Thickness-dependent topological phase transition and Rashba-like preformed topological surface states of α-Sn(001) thin films on InSb(001). Phys Rev B 105, 075109 (2022).

Mutch, J. et al. Evidence for a strain-tuned topological phase transition in ZrTe5. Sci Adv5, eaav9771 (2019).

Lin, C. et al. Visualization of the strain-induced topological phase transition in a quasi-one-dimensional superconductor TaSe3. Nat Mater 20, 1093–1099 (2021).

Jozwiak, C. et al. Spin-polarized surface resonances accompanying topological surface state formation. Nat Commun 7, 13143 (2016).

Menshchikova, T. V., Eremeev, S. V., Koroteev, Yu. M., Kuznetsov, V. M. & Chulkov, E. V. Ternary compounds based on binary topological insulators as an efficient way for modifying the Dirac cone. JETP Lett 93, 15–20 (2011).

Jin, H., Song, J.-H., Freeman, A. J. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Candidates for topological insulators: Pb-based chalcogenide series. Phys Rev B 83, 041202 (2011).

Menshchikova, T. V., Eremeev, S. V. & Chulkov, E. V. Electronic structure of SnSb2Te4 and PbSb2Te4 topological insulators. Appl Surf Sci 267, 1–3 (2013).

Souma, S. et al. Topological surface states in lead-based ternary telluride Pb(Bi1−xSbx)2Te4. Phys Rev Lett 108, 116801 (2012).

Kuroda, K. et al. Experimental verification of PbBi2Te4 as a 3D topological insulator. Phys Rev Lett 108, 206803 (2012).

Eremeev, S. V. et al. Atom-specific spin mapping and buried topological states in a homologous series of topological insulators. Nat Commun 3, 635 (2012).

Yaji, K. et al. High-resolution three-dimensional spin- and angle-resolved photoelectron spectrometer using vacuum ultraviolet laser light. Review of Scientific Instruments 87, (2016).

Eremeev, S. V., Silkin, I. V., Menshchikova, T. V., Protogenov, A. P. & Chulkov, E. V. New topological surface state in layered topological insulators: Unoccupied Dirac cone. JETP Lett 96, 780–784 (2013).

Yan, B. et al. Topological states on the gold surface. Nat Commun 6, 10167 (2015).

Zhang, P. et al. Multiple topological states in iron-based superconductors. Nat Phys 15, 41–47 (2019).

Shockley, W. On the surface states associated with a periodic potential. Physical Review 56, 317–323 (1939).

Hatta, S., Aruga, T., Ohtsubo, Y. & Okuyama, H. Large Rashba spin splitting of surface resonance bands on semiconductor surface. Phys Rev B 80, 113309 (2009).

Ohtsubo, Y., Yaji, K., Hatta, S., Okuyama, H. & Aruga, T. Two-dimensional states localized in subsurface layers of Ge(111). Phys Rev B 88, 245310 (2013).

Stolwijk, S. D., Sakamoto, K., Schmidt, A. B., Krüger, P. & Donath, M. Thin line of a Rashba-type spin texture: Unoccupied surface resonance of Tl/Si(111) along \(\Gamma\bar{M}\). Phys Rev B 90, (2014).

Yaji, K. et al. Experimental evidence for two-dimensional states localized in subsurface region of Ge(111). J Electron Spectros Relat Phenomena 201, 92–97 (2015).

Hattori, Y., Tokumoto, Y. & Edagawa, K. Optimizing composition of Pb(Bi1−xSbx)2Te4 topological insulator to achieve a bulk-insulating state. Phys Rev Mater 1, 074201 (2017).

Shimojima, T., Okazaki, K. & Shin, S. Low-Temperature and High-Energy-Resolution Laser Photoemission Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 072001 (2015).

Yaji, K. et al. Spin-dependent quantum interference in photoemission process from spin-orbit coupled states. Nat Commun 8, 14588 (2018).

OpenMX (Open source package for Material eXplorer), Available: http://www.openmx-square.org/.

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys Rev B 67, 155108 (2003).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kotaka, H., Ishii, F. & Saito, M. Rashba effect on the structure of the Bi one-bilayer film: fully relativistic first-principles calculation. Jpn J Appl Phys 52, 035204 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ryo Noguchi for Igor Macro for data analysis and Ayumi Harasawa for technical support before the experiments. The DFT calculations in this study were performed on the Numerical Materials Simulator at NIMS. The present work was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (Grant Nos. JP18K03484, JP21K04633, JP21K18898, JP21H04439, JP22H01765) and the Innovative Science and Technology Initiative for Security, ATLA, Japan (Grant No JPJ004596) and by MEXT Q-LEAP (Grant No. JPMXS0118068681). MANA is supported by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KY conceived the research. KY, YH, and ST carried out ARPES and SARPES measurements under the support of FK, YF, KK, and TK. YH fabricated and characterized the sample under the support of YT, KE and TT. SY performed DFT calculations under the support of YY. All authors discussed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaji, K., Hattori, Y., Yoshizawa, S. et al. Visualization of spin-polarized surface resonances in Pb-based ternary topological insulators. Sci Rep 14, 25868 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76493-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76493-9