Abstract

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) can cause mild diarrhea even severe hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Shiga toxin (Stx) is the primary virulence factor. Two Stx types and several subtypes have been identified. STEC strains encoding stx2f (Stx2f-STECs) are frequently identified from pigeons. Stx2f was initially considered to be associated with mild symptoms, more recently Stx2f-STECs have been isolated from HUS cases, indicating their pathogenic potential. Here, we investigated the prevalence of Stx2f-STECs among domestic pigeons in two regions in China, characterized the strains using whole-genome sequencing (WGS), and assessed the Stx2f transcriptions. Thirty-two Stx2f-STECs (4.36%) were culture-positive out of 734 fecal samples (one strain per sample). No other stx subtype-containing strain was isolated. Four serotypes and two sequence types were determined, and a novel sequence type ST15057 was identified. All strains harbored the E. coli attaching and effacing gene eae. Two types of Stx2f prophages were assigned. Stx2f-STECs showed variable Stx transcription levels induced by mitomycin C. Whole genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (wgSNP) analysis revealed different genetic backgrounds between pigeon-derived strains and those from diarrheal or HUS patients. In contrast, pigeon-derived Stx2f-STECs from diverse regions exhibited genetic similarity. Our study reports the prevalence and characteristics of Stx2f-STECs from pigeons in China. The pigeon-derived strains might pose low public health risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is a significant zoonotic pathogen, which can cause mild diarrhea, gastroenteritis, and even severe life-threatening complication hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in humans1,2. The key virulence factor of STEC is Shiga toxin (Stx), an essential factor for the development of HUS3,4. The stx gene is located downstream of the Q gene encoding late promotor in lysogenized lambdoid prophages. The transcription and expression of Stx is regulated by the Stx prophages. Stx-converting phages are highly mobile genetic elements that play an important role in horizontal gene transfer and STEC pathogenies5.

Stx can be distinguished into two immunologically distinct types (Stx1 and Stx2)6. Based on variations in amino acid sequences, various subtypes, i.e., four Stx1 (Stx1a, Stx1c, Stx1d, and Stx1e) and fifteen Stx2 (Stx2a to Stx2o) subtypes have been reported7,8. Shiga toxin subtypes display notable variances in biological activity, including serological reactivity, receptor binding, and the potency of the toxin. These differences are instrumental in determining the host specificity and the resultant health outcomes after human infection. Stx2a- and Stx2d-producing strains are more often associated with severe disease than Stx1-producing strains9,10. Stx2f subtype is highly distinct from other known Stx2 subtypes when comparing nucleotide and amino acid sequences, and this may lead to those most routine tests cannot efficiently identify this subtype11, its clinical relevance might thus have been underestimated12. Stx2f-STEC is known to cause relatively mild disease in humans, however, there were sporadic case reports of fatal illness associated with human Stx2f-STEC infection12, suggesting its clinical relevance.

Besides Stx, other virulence factors also play a role in STEC pathogenicity. For example, intimin encoded by eae gene on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island, plays an important role in intestinal colonization13, and is responsible for host specificity and tissue tropism14. The LEE encodes a type III secretion system (TTSS), which is responsible for the attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions on intestinal epithelia14. Several eae subtypes have been identified based on the heterogeneous 3’ region, which encoding the intimin cell-binding domain13.

Ruminants, primarily cattle, are regarded as the natural reservoir of STEC. Birds and pigs have also been reported to carry STEC15. STEC strains harboring Stx2e and Stx2f are host preference. Stx2e-producing strains have been mainly reported in swine and associated with porcine edema disease16. STECs harboring the stx2f subtype are frequently found in bird species and especially in pigeons, but have never been reported in ruminants17. Stx2f subtype has also been detected in Escherichia albertii strains from various bird species worldwide18,19. The prevalence and characteristics of Stx2f-STEC strains in pigeon have been reported in other countries20,21,22, yet it was largely unknown in China.

In the present study, we depicted the prevalence and characteristics of the Stx2f subtype-producing strains from pigeons in two provinces in China. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed to characterize the genomic features of Stx2f-STEC strains. We analyzed the phylogenetic relatedness of Stx2f-STEC strains in this study and those reported from diverse sources, and further assessed Stx2f transcription levels to demonstrate their pathogenic potential.

Results

Prevalence of STEC in pigeons

Only stx2f gene was positive when examining the fecal samples enrichments. Finally, twenty-nine Stx2f-STEC strains were isolated from pigeons in three farms in Wujiaqv City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the overall isolation rate in this region was 7.44% (29/390). Three Stx2f-STEC strains were isolated in one farm in Zaozhuang City, Shandong Province, and the isolation rate was 0.87% (3/344). In total, 32 Stx2f-STEC strains were isolated from 734 pigeon fecal samples, giving a culture positive rate of 4.36% (32/734) (Table 1).

In Wujiaqv City, samples from Farm B collected during March and April yielded a single Stx2f-STEC strain each month, the isolation rates were 2.86% (1/35) and 5.00% (1/20), respectively. In farm C, 24 strains were isolated from samples collected in July (48%, 24/50), while no strains were detected from samples collected in March. In farm F, samples were collected in July, and three strains were isolated (6.00%, 3/50). In Zaozhuang City, Stx2f-STEC strains were isolated exclusively from Farm I in March (4.00%, 2/50) and April (4.00%, 1/25). No Stx2f-STEC strains were isolated in samples collected from June and July in Farm I.

Molecular characteristics of pigeons-derived Stx2f- STEC isolates

WGS data analysis revealed four different O: H serotypes. O4:H2 was the most predominant serotype accounting for 53.13% (17/32) of all strains. O45:H2 and O75:H2 were identified in six strains, respectively. Three strains were typed as O128:H2. Two MLST sequence types (STs) were assigned, i.e., ST20 (26 strains), ST15057 (6 strains) (Table 2).

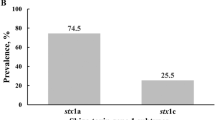

Multiple virulence factors genes were identified in the 32 Stx2f-STEC strains (Table S1a). These virulence genes were classified into several groups based on their functions: adherence, invasion, effector system, exotoxin, immune modulation, nutritional/metabolic factor, and regulation. The STEC strains exclusively harbored the stx2f subtype. All the 32 Stx2f-STEC strains carried intimin encoding gene eae, belonging to beta3 (β3) subtype. The enteroaggregative E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin (EAST1) encoding gene astA was also detected in 32 strains. The presence/absence of eae and astA among 25 pigeon- and human-derived reference Stx2f-STEC strains were also assessed. All harbored the eae gene, including α2, β2, β4, ι1, and ξ subtypes (Fig. 1). Except strain M885 (GenBank: GCA_900007725.1) and M900 (GenBank: GCA_900007735.1), all other strains possessed the astA gene. The bundle-forming pilus (BFP) encoding genes bfpB-K, were identified in all 32 strains.

Phylogenetic tree based on core-genome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using the Maximum-Likelihood method. Colored circles indicate strains in this study isolated from different farms. The colored rectangle indicates the sample regions of the strains. The background color of the strain number indicates the sources of the strains. MLST type, serotype, and accession number of all strains are shown. UNK indicates the sequence type of the reference stain is unknown.

Sixty-one AMR genes were identified, 36 of them were efflux-related transporter protein-encoding genes (Table S1b). AMR genes associated with resistance to peptide antibiotics (bacA, baeR, baeS, eptA, pmrF, ugd) and class C β-lactamase (blaEC-18, ampH, and ampC1) were found in all strains. The other predominant AMR genes were dfrA14 (n = 22), tet(A) (n = 23), oqxA (n = 16), oqxB (n = 16), qnrS1 (n = 22), floR (n = 16), cmlA1 (n = 1), cmlA5 (n = 6), aadA2 (n = 1), ant(3’’)-IIa (n = 7), blaTEM-181 (n = 16), and sul3 (n = 1).

PlasmidFinder identified the presence of IncFIB (AP001918) plasmids replicons in the 32 Stx2f-STEC strains in this study, IncFII (pCoo) was identified in 24 strains. Other plasmids replicons such as IncFII (pHN7A8), IncFII (pSFO), IncHI2, IncHI2A, IncI1-I (Alpha), IncI2 (Delta), and pKPC-CAV1321 were also identified (Table S1c). In silico analysis revealed that the IncFIB (AP001918) was located on the same contig as bfpB-K.

Genetic feature of Stx2f-converting prophages

Fifteen genomes of Stx2f-STEC strains were excluded due to limited length of stx-containing contigs, seventeen draft genomes were thus used for analyzing. The comparison of the stx2f-containing contigs demonstrated that there were two types of Stx2f prophages named as Group Type 1 (GT1) and Group Type 2 (GT2) (Table S2). Variability was observed at the insertion sites and phage integrase of the two prophage types, four Stx2f prophages of GT1 were inserted at yecE gene (DUF72 domain-containing protein YecE), while thirteen Stx2f prophages of GT2 were inserted at a response regulator receiver domain protein encoding gene (GenBank: JAUKLQ010000056.1:1897.3645) (Fig. 2). Besides the identical integrase (NCBI Reference Sequence: WP_062860143) possessed by the seventeen Stx2f prophages, tyrosine-type recombinase protein accession number (NCBI Reference Sequence: HAX3195029) was also found in Stx2f prophage of GT2.

Easyfig plot comparison of the Stx2f prophages. Stx2f prophages in this study were assigned into two phage groups, Group Type 1 (GT1) and Group Type 2 (GT2). The phi467 was a reference Stx2f prophage. Coding sequences and gene directions are represented by arrows. The asterisk (*) signifies that downstream of the phage could not be conclusively identified. The gray bars represent the nucleotide identity as indicated in the legend.

Stx2f prophage phi467 (GenBank: LN997803.1) was possessed by a HUS-derived Stx2f-STEC strain EF467 (GenBank: GCA_013172765.1). GT2 prophage was virtually identical to the reference phi467. Among the Stx2f prophages, the upstream sequence of the repressor protein (CI) was different, while the downstream sequence was identical (Fig. 2). When comparing the Stx2f prophages in this study with reference Stx2a prophage 933 W (GenBank: AF125520.1), high diversity was observed (Figure S1). The nucleotide sequences between the Stx2a prophage and the Stx2f prophage were quite different. tRNA genes are usually located upstream of Shiga toxin coding gene stx, while in Stx2f prophage, two tRNA genes were located downstream of stx2f.

SNP-based phylogeny relationship of Stx2f-producing strains

To assess the phylogenetic relationships of the Stx2f-STEC strains from this study and reference strains derived from diverse sources, whole-genome SNP-based phylogeny trees were constructed. Strains isolated from the same source exhibited the tendency to cluster together. Four main clusters were observed based on the source of strains (Fig. 1). Pigeon-derived strains from different regions clustered closely (Cluster 1). Human-derived strains sharing same serotype and MLST type as pigeon-derived strains also clustered within Cluster 1, while most of other human-derived strains were grouped at Cluster 2. Strains from patients with HUS exhibited different serotypes and MLST types from other source strains and formed separate Cluster 3 and Cluster 4. Pairwise SNP distances were calculated to illustrate the dissimilarity among the strains within Cluster 1 (Figure S2). The genetic divergence, as measured by SNP distance, among strains isolated from Farm I was less than 29 SNPs, within Farm F it was less than 25 SNPs, in Farm B it was 20 SNPs, and across Farm D it spanned a more variable spectrum, ranging from 6 to 854 SNPs. The SNP distance among pigeon-derived strains in this study and the reference human diarrhea-derived strains was ≥ 591, when comparing pigeon-derived strains in this study and the reference pigeon-derived strains, the SNP distance was ≥ 538.

Stx2f mRNA expression levels

To assess the transcriptional activity of Stx2f, strains were induced by mitomycin C, qRT-PCR result revealed variable stx2f expression levels among the strains (Fig. 3). Notably, all strains exhibited a more than one-fold increase of stx2f expression level after mitomycin C treatment, as compared to the levels without mitomycin C treatment. A higher expression level of stx2f gene were observed in strain STEC1636 and STEC1632 with the transcript level 78.6- and 53.3-fold. The lowest expression level was observed in STEC1660 with the transcript level 3.5-fold.

Fold change in Stx2f mRNA expression in the induced state relative to the basal state. The dotted red line indicates one-fold level. Levels of stx2f mRNA expression were normalized against gapA. Non-induced stx2f mRNA levels of each strain were used as calibrators (defined as 1). Data are represented by mean ± SD (standard deviation) (n = 3).

Discussion

In this study, the isolation rate of Stx2f-STEC strains from pigeons was 7.44% and 0.87% in two provinces in China, which is lower than those reported in other countries. For instance, Stx2f-STECs were isolated from 9%~25.8% of pigeon fecal samples from different cities in Iran21. In Italy, the prevalence of Stx2f-STEC strains in pigeons was 8%~12.4%22. The prevalence rate of Stx2f-STEC has also been reported in pigeon of Finland (3.0%, 1/33) and Japan (3.0%, 2/67)23,24. Interestingly, there was variability in the isolation rates of STEC across different farms within the same region, which might be attributed to differences in pigeon breeds and the specific conditions of their breeding environments25.

Stx2f has a low homology with other Stx2 subtypes, commercial PCR assays cannot detect this variant26,27. Reports from Germany described the isolation of Stx2f-STEC strains from human diarrheal stool specimens28. In Belgium and Netherlands, Stx2f-STECs infections represented an estimated respectivev16% and 20% of all STEC infections29,30. Although Stx2f-STECs are considered less virulent than Stx2a-STEC O157 infections, Stx2f-STEC infections are more common than anticipated. Several studies showed that Stx2f-STECs are linked with severe disease in humans, HUS caused by Stx2f-STEC strains have been reported in England, Netherlands, Austria, and Italy29,31,32. Although there has been no report of human Stx2f-STEC infection in China so far, in our study, pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains were continuously detected in different months in two farms, the persistent circulation increases the chance of cross-species transmission and potential risk of human infection.

We characterized the molecular characteristics of Stx2f-STEC strains, strains belonging to three serotypes (O128:H2, O4:H2, and O45:H2) and ST20 were predominant in pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains, and different from the exclusively human-derived serotypes such as O63:H6, O113:H6, O125:H6, and O145:H3420. It is noteworthy that O45:H2 and O128:H2 were also reported in clinical isolates in Germany28. The overlaps in serotypes among human and pigeon isolates were limited. In this study, we isolated strains characterized by the serotype O75:H2 and the sequence type ST15057. Notably, this particular sequence type and serotype combination has not been previously documented in Stx2f-STEC strains, thereby broadening our understanding of the genetic traits typically associated with pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains, which are known for their relative conservatism.

In our study, although human- and pigeon-derived strains phylogenetically clustered in cluster 1, the large SNP distance among strains within this cluster indicates genetic differences between the two sources of strains. The result supports previous findings, suggesting that common human-associated Stx2f-STEC strains do not originate from the pigeon reservoir20, instead, transmission of Stx2f-STEC primarily occurs through person-to-person contact. The pigeon-derived strains in this study and reference HUS patient-derived strains were phylogenetically separated. This indicates that HUS-associated Stx2f-STEC strains constitute a unique subgroup within the broader Stx2f-STEC population. Previous studies have revealed that HUS-derived Stx2f-STEC strains are more similar to the non-O157 STEC isolated from patients with severe disease, rather than Stx2f-STEC isolated from humans with mild diarrhea or asymptomatic pigeons20. This suggested that these human-associated and HUS-derived Stx2f-STEC strains are not inherently part of the pigeon gut microbiota as those pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains, instead, the Stx2f-STEC strains causing HUS might emerged due to the acquisition of the Stx2f phage by E. coli strains with typical HUS-associated virulence genes31.

All the 32 pigeon-derived isolates and the 25 pigeon- and human-derived reference strains in the current study possessed the eae and most of them (96.5%, 55/57) harbor astA genes. Similarly, the widespread occurrence of eae, and astA gene were reported previously in Stx2f-STEC strains. It should be particularly taken into consideration that the high prevalence of eae and astA gene among Stx2f-STEC strains, indicated that the Stx2f-STEC strains are more tend to form hybrid strains, the risk of emerging highly pathogenic hybrid STEC/EPEC strains and enteroaggregative hemorrhagic pathotype (EAHEC) should not be ignored33. The eae-positive STEC strains are more related to severe clinical outcome34. However, eae subtype β3 was related to non-HUS strains, this might indicate the low pathogenic potential of those eae β3-carried strains. The different distribution of eae subtypes of strains in this study and reference strains suggested diverse genetic backgrounds among pigeon- and human-derived strains. This was consistent with a study in the Netherlands that demonstrated considerable differences between pigeon and human Stx2f-STEC genomes20. In addition, the pigeon-derived strains in our study and the reference strains exhibited distinct eae subtypes. Other virulence effectors such as bfpA and cdt were not detected in our pigeon-derived strains. Studies have reported that a 85 kb plasmid that encoded bfpA and cdt in Stx2f-STEC strains may facilitate transmission within the human population12. In our study, the plasmid replicons IncFIB (AP001918) were found in the same contig as BFP encoding genes, suggesting these genes may be co-localized on the same plasmid, given that BFP is frequently linked to FIB/FIIA plasmid families20, the role of this plasmid in pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains and the role of the animal reservoir pigeon in strain transmission to humans needs further research.

In our study and previous research, the Stx2f-STEC strains exclusively carry the Shiga toxin 2f, differ in numerous STEC strains harbor multiple Shiga toxin types or subtypes21. This uncommon characteristic might relate to the distinctive Stx2f prophage, it prevented the invasion of other Stx phages during STEC evolution. In our study, the insertion sites among the two Stx2f prophages, yecE was commonly found in Stx2k and Stx2e prophages16,35, whereas another insertion site, a response regulator receiver domain protein, was rarely reported. Although the two insertion sites were different from ssrA gene found in a HUS-derived STEC strain, the high similarity of GT2 prophages in this study to the Stx2f prophage carried by a HUS-derived STEC strain suggests the pathogenic potential of strains carrying GT2 Stx2f phage. Our study showed that the genomic diversity between Stx2f prophages mainly occurs at their early regions between integrase and repressor coding genes. This region was part of early regulation that mediates the switch between repression and induction of the prophage, thus influencing the expression level of the Shiga toxin as well as the potential to produce phage particles without inducing agents of STEC strains. No significant differences in stx2f mRNA expression level were found between strains carrying GT1 and GT2 prophages. Since the genes in the different regions mainly encoded hypothetical proteins among Stx2f prophages, the function of those genes and their effects on toxin expression should be further investigated.

The higher stx2f mRNA producing strains STEC1636 and STEC1632 belonged to the same serotype O45:H2 and MLST 20, with an SNP distance of 20, although six strains possessed the same serotype O45:H2 and MLST 20 in this study, the SNPs between the higher stx2f mRNA producing strain STEC1636 and the other five strains were 20 to 205. This result indicated that the two higher stx2f mRNA producing strains might possess genes influencing stx2f expression that were distinct from other strains.

To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the prevalence and molecular traits of Stx2f-STEC strains from pigeons in China. Genomic characterization revealed genetic similarity of pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains from different countries, a novel sequence type ST15057 was found in Stx2f-STEC strains. Two genome types of Stx2f prophages were defined. Stx2f-STEC strains were phylogenetically clustered based on sources of strains. Stx2f mRNA expression levels of Stx2f-STEC strains in this study could be detected after inducing by MMC. The pigeon-derived strains might pose low public health risk. Further studies are essential to investigate the prevalence of Stx2f-STEC strains among humans in the two regions in China, and to assess their transmission routes and pathogenic potentials to humans.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and isolation of Stx2f-STEC strains

Fecal sampling from domestic pigeons was carried out in two geographical regions in China. Briefly, 390 fecal samples were collected from six small-scale family pigeon farms in Wujiaqv, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in March, April, and July in 2023. A total of 344 fecal samples were collected from three small-scale family pigeon farms in Zaozhuang, Shandong Province in March, April, June, and July in 2023. Those pigeon feces were collected from specific individual birds. The fresh fecal samples were collected in 5 mL sterile tubes containing Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with 30% glycerol, and transported immediately to the laboratory in the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC under cold condition. STEC strains were isolated and confirmed by methods described previously36. Briefly, all samples were homogenized in 5 mL E. coli broth (EC broth, Land Bridge, Beijing, China). The enrichments were examined by PCR for the presence of stx, due to high dissimilarity of stx2f from other stx2 subtypes, the presence of stx2f was tested using primer pairs 5′-TCTCAGGGTGGTRTTTCTGTT-3′ and 5′-AACAATGGCTGCAAATTCCAT-3′, in addition the primer pairs stx1 (5′-AAATCGCCATTCGTTGACTACTTCT-3′ and 5′-TGCCATTCTGGCAACTCGCGATGCA-3′), stx2 (5′-CAGTCGTCACTCACTGGTTTCATCA-3′ and 5′-GGATATTCTCCCCACTCTGACACC-3′) were used to test the presence of other stx1/stx2 subtypes. Samples positive for stx were plated onto MacConkey agar (MAC, Land Bridge, Beijing, China) and CHROMagar ECC agar (CHROMagar, Paris, France). After overnight incubation at 37 °C, pink or colorless colonies on Mac agar and green-blue colonies on ECC agar were picked and tested for presence of stx1/stx2/stx2f by a single-colony PCR assay, API 20E biochemical test strips (bioMérieux, Lyon, France) were used to confirm that all stx2f-containing isolates were E. coli. One isolate per sample was kept for further analysis.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and genome assembly

Bacterial DNA of all isolates was extracted from overnight culture using Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Library preparation and WGS were performed at BGI, China. 150 bp paired-end short reads libraries were prepared and sequenced using MGISEQ-2000 platform (MGI Tech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Low-quality reads (Q-value ≤ 20) and adapter sequences were filtered by SOAPnuke and then the reads were de novo assemble using SPAdes version 3.9.037. All the assembled sequences were uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (BioProject: PRJNA1064233).

WGS-based molecular characterization of Stx2f-STEC strains

The genome assemblies were compared with SerotypeFinder database (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) (accessed on 10 November 2023), VFDB database (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) (accessed on 10 November 2023), Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (http://arpcard.mcmaster.ca) (accessed on 15 November 2023), an in-house stx subtyping database included all identified stx1 (stx1a, stx1c, and stx1d), and stx2 (stx2a to stx2o) subtypes, an in-house eae subtyping database and PlasmidFinder database (http://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/) (accessed on 25 July 2024), to determine the serotypes, virulence factors genes, antimicrobial resistance genes, stx subtypes, eae subtypes, and plasmid types respectively, using ABRicate version 0.8.10 with default parameters. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) alleles of seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, recA) was performed in silico through the Seemann T, mlst (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) (accessed on 20 November 2023).

Identification and characterization of Stx2f prophages

The partial Stx2f prophage sequences were identified from the draft Stx2f-STEC genomes using methods previously described35. Briefly, the stx located contigs were searched and extracted from draft genomes by using Seqkit version 2.2.0, PHAge Search Tool Enhanced Release (PHASTER, http://phaster.ca/) was used to identify Stx prophages (accessed on 25 November 2023). The RAST server (http://rast.nmpdr.org/) was used to annotate the genomes of Stx prophages (accessed on 26 November 2023). The phage insertion site was defined as the gene adjacent to the integrase. The sequences of Stx2f prophage were compared and visualized in details using Easyfig38.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogeny of Stx2f-STECs

The genomic relatedness of pigeon-derived Stx2f-STEC strains obtained in this study as well as 25 reference Stx2f-STEC strains from other sources was assessed by constructing a whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (wgSNP) phylogeny. The selection of the 25 reference Stx2f-STEC strains was based on their isolation sources, including pigeon, HUS cases, and diarrheal patients. The genomes of reference Stx2f-STEC strains isolated from pigeons, diarrhea patients, and HUS patients were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The core alignment of the SNPs was obtained by using snippy-multi in Snippy version 4.3.6 (https://github.com/tseemann/ snippy) (accessed on 10 November 2023) with default parameters. Stx2f-STEC strain STEC1672 in this study (GenBank: GCA_035967375.1) was used as a reference. Gubbins version 2.3.439 was then used to concatenate SNPs and remove recombinations from core SNP alignments, and construct a maximum likelihood tree based on filtered SNP alignments. SNP distances were executed using snp-dists v0.7.0. (https://github.com/tseemann/snp-dists) (accessed on 20 November 2023). The phylogenetic tree was visualized and annotated by the web-tool ChiPlot (https://www.chiplot.online/#Phylogenetic-Tree) (accessed on 25 November 2023)40.

RNA extraction and mRNA expression level of stx2f

The Stx2f-STEC strains were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) to the early-exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.6). Then each culture was subdivided into two flasks, one was induced by Mitomycin C (MMC) at a final concentration of 0.5 µg/mL, the other was used as non-induced control. The cultures were then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 3 h, and then the total RNA was extracted and purified by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amount of total RNA was determined by a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was accomplished using HiScript II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The primer pairs for stx2f (5′- AGAGGAGAGGAAGGGGTAAG − 3′ and 5′- TCACGGAACGAACTGAATAAC − 3′), and for the housekeeping gene gapA (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A) (5′-TATGACTGGTCCGTCTAAAGACAA-3′ and 5′-GGTTTTCTGAGTAGCGGTAGTAGC-3′) were used41. The gapA gene was used for a within-sample normalization. The RT-qPCR cycle parameters were as follows: 50 °C (15 min), 95 °C (30 s), 40 cycles of 95 °C (10 s), 55 °C (30 s-read fluorescence), and followed by melt curve analysis. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. The relative difference in gene expression was calculated using the 2−△△CT method. The Stx expression levels under mitomycin C-inducing relative to non-induced ones were calculated. The bar plots were visualized using GraphPad Prism.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention (protocol code ICDC-202114); and all methods were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Data availability

The genome data presented in this study are publicly available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with accession numbers provided in Fig. 2 and Table S2.

References

Smith, J. L. & Fratamico, P. M. t. Gunther, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 86, 145–197 (2014).

Tarr, P. I., Gordon, C. A. & Chandler, W. L. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 365 (9464), 1073–1086 (2005).

Kruger, A. & Lucchesi, P. M. Shiga toxins and stx phages: highly diverse entities. Microbiol. (Reading). 161 (Pt 3), 451–462 (2015).

Steyert, S. R. et al. Comparative genomics and stx phage characterization of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 133 (2012).

Rodríguez-Rubio, L. et al. Bacteriophages of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and their contribution to pathogenicity. Pathogens, 10(4). (2021).

Bryan, A., Youngster, I. & McAdam, A. J. Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli. Clin. Lab. Med. 35 (2), 247–272 (2015).

Scheutz, F. et al. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing stx nomenclature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50 (9), 2951–2963 (2012).

Lindsey, R. L. et al. Identification and characterization of ten Escherichia coli strains encoding novel Shiga toxin 2 subtypes, Stx2n as well as Stx2j, Stx2m, and Stx2o, in the United States. Microorganisms. 11 (10), 2561 (2023).

Scheutz, F. Taxonomy meets public health: the case of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr., 2(3). (2014).

Panel, E. B. et al. Pathogenicity assessment of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and the public health risk posed by contamination of food with STEC. EFSA J. 18 (1), e05967 (2020).

Cointe, A. et al. Be aware of shiga-toxin 2f-producing Escherichia coli: case report and false-negative results with certain rapid molecular panels. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 98 (4), 115177 (2020).

Den Ouden, A. et al. Escherichia coli encoding Shiga toxin subtype Stx2f causing human infections in England, 2015–2022. J. Med. Microbiol., 72(6). (2023).

Liu, Q. et al. Genetic diversity and expression of Intimin in Escherichia albertii isolated from humans, animals, and food. Microorganisms, 11(12). (2023).

Hua, Y. et al. Molecular characteristics of Eae-positive clinical Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in Sweden. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9 (1), 2562–2570 (2020).

Persad, A. K. & LeJeune, J. T. Animal reservoirs of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr, 2(4): p. EHEC-0027-2014. (2014).

Yang, X. et al. Genomic characteristics of Stx2e-producing Escherichia coli strains derived from humans, animals, and meats. Pathogens, 10(12). (2021).

Koochakzadeh, A. et al. Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing and Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in wild and pet birds in Iran. Brazilian J. Poult. Sci. 17, 445–450 (2015).

Liu, Q. et al. Identification and genomic characterization of Escherichia albertii in migratory birds from Poyang Lake, China. Pathogens, 12(1). (2022).

Hinenoya, A. et al. Detection, isolation, and molecular characterization of Escherichia albertii from wild birds in west Japan. Jpn J. Infect. Dis. 75 (2), 156–163 (2022).

van Hoek, A. et al. Comparative genomics reveals a lack of evidence for pigeons as a main source of stx(2f)-carrying Escherichia coli causing disease in humans and the common existence of hybrid Shiga toxin-producing and enteropathogenic E. Coli pathotypes. BMC Genom. 20 (1), 271 (2019).

Askari Badouei, M. et al. Molecular characterization, genetic diversity and antibacterial susceptibility of Escherichia coli encoding Shiga toxin 2f in domestic pigeons. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 59 (4), 370–376 (2014).

Morabito, S. et al. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in feral pigeons. Vet. Microbiol. 82 (3), 275–283 (2001).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Eae- and stx-positive strains of Escherichia coli from wild birds in the immediate environment of Tokyo Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 (1), 292–295 (2009).

Kobayashi, H., Pohjanvirta, T. & Pelkonen, S. Prevalence and characteristics of intimin- and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from gulls, pigeons and broilers in Finland. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 64 (11), 1071–1073 (2002).

Ghanbarpour, R. & Daneshdoost, S. Identification of Shiga toxin and intimin coding genes in Escherichia coli isolates from pigeons (Columba livia) in relation to phylotypes and antibiotic resistance patterns. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 44 (2), 307–312 (2012).

De Rauw, K. et al. Detection of Shiga toxin-producing and other diarrheagenic Escherichia coli by the BioFire FilmArray(R) gastrointestinal panel in human fecal samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35 (9), 1479–1486 (2016).

Staples, M. et al. Evaluation of the SHIGA TOXIN QUIK CHEK and ImmunoCard STAT! EHEC as screening tools for the detection of Shiga toxin in fecal specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 87 (2), 95–99 (2017).

Prager, R. et al. Escherichia coli encoding Shiga toxin 2f as an emerging human pathogen. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 299 (5), 343–353 (2009).

De Rauw, K., Jacobs, S. & Pierard, D. Twenty-seven years of screening for Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in a university hospital. Brussels, Belgium, 1987–2014. PLoS One. 13 (7), e0199968 (2018).

Friesema, I. et al. Emergence of Escherichia coli encoding Shiga toxin 2f in human shiga toxin-producing E. Coli (STEC) infections in the Netherlands, January 2008 to December 2011. Euro. Surveill. 19 (17), 26–32 (2014).

Grande, L. et al. Whole-genome characterization and strain comparison of VT2f-producing Escherichia coli causing hemolytic uremic syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22 (12), 2078–2086 (2016).

Friesema, I. H. et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Escherichia coli O8:H19 and shiga toxin 2f gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21 (1), 168–169 (2015).

Brzuszkiewicz, E. et al. Genome sequence analyses of two isolates from the recent Escherichia coli outbreak in Germany reveal the emergence of a new pathotype: Entero-Aggregative-Haemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EAHEC). Arch. Microbiol. 193 (12), 883–891 (2011).

Matussek, A. et al. Genome-wide association study of hemolytic uremic syndrome causing Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from Sweden, 1994–2018. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 42 (6), 771–779 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. High prevalence and persistence of Escherichia coli strains producing Shiga toxin subtype 2k in goat herds. Microbiol. Spectr. 10 (4), e0157122 (2022).

Fan, R. et al. High prevalence of non-O157 shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle detected by combining four selective agars. BMC Microbiol. 19 (1), 213 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience. 7 (1), 1–6 (2018).

Sullivan, M. J., Petty, N. K. & Beatson, S. A. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 27 (7), 1009–1010 (2011).

Croucher, N. J. et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (3), e15 (2015).

Xie, J. et al. Tree visualization by one table (tvBOT): a web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 51 (W1), W587–W592 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Global transcriptional and phenotypic analyses of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain Xuzhou21 and its pO157_Sal cured mutant. PLoS One. 8 (5), e65466 (2013).

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 82072254.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. administrated the project, Y.M., F.C, H.W., and Q. L. participated in the investigation, Y.M., F.C., and B.D collected the samples; X.Y. and H.W. performed the experiments, X.Y., X.S., and P.Z. analyzed the data; X.Y. wrote the original draft, the other authors reviewed and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Ma, Y., Chu, F. et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains producing Shiga Toxin 2f subtype from domestic Pigeon. Sci Rep 14, 24481 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76523-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76523-6