Abstract

Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome (CHS) is a serious complication after bypass surgery in Moyamoya disease (MMD), with autoregulatory dysfunction being a major pathogenesis. This study investigated the change of perioperative autoregulation and preoperative prognostic potentials in MMD with postoperative CHS. Among 26 hemispheres in 24 patients with adult MMD undergoing combined bypass, 13 hemispheres experienced postoperative CHS. Arterial blood pressure and cerebral blood flow velocity were perioperatively measured with transcranial Doppler ultrasound during resting and the Valsalva maneuver (VM). Autoregulation profiles were discovered in both the CHS and non-CHS groups using mean flow index (Mxa), VM Autoregulatory Index (VMAI), and a new metric termed VM Overshooting Index (VMOI). The CHS group had inferior autoregulation than the non-CHS group as indicated by VMOI on preoperative day 1 and postoperative 3rd day. Deteriorated autoregulation was observed via Mxa in the CHS group than in the non-CHS group on the postoperative 3rd and discharge days. Postoperative longitudinal autoregulation recovery in the CHS group was found in a logistic regression model with diminished group differences over the time course. This work represents a step forward in utilizing autoregulation indices derived from physiological signals, to predict the postoperative CHS in adult MMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a progressive occlusive cerebrovascular disease characterized by stenosis in the internal carotid arteries and the development of collateral vessels1. Although the pathogenesis of MMD is not fully understood, bypass surgery has shown favorable outcomes in preventing ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in patients with MMD2,3,4,5. Bypass surgery is performed in either a direct6or an indirect2,3manner and in combination to achieve maximal augmentation of cerebral perfusion4,7.

The long-term outcomes of bypass surgery in MMD patients are well documented2,4; however, numerous postoperative complications have been reported8,9,10. Among them, cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome (CHS), one of the major complications, is characterized by radiologic evidence of focal hyperperfusion around the anastomosed arteries and a spectrum of corresponding clinical symptoms such as headache, transient neurological deficits, seizure and intracerebral hemorrhage11,12. In patients with MMD who underwent revascularization surgery, CHS incidence varies from 21.5–31.5%4,11,12,13. Postoperative CHS is believed to be associated with several factors, including impaired cerebral autoregulation and elevated cerebral blood flow (CBF)14,15.

Cerebral autoregulation refers to the ability of cerebral blood vessels to maintain a constant CBF regardless of the changes in arterial blood pressure (ABP) (or cerebral perfusion pressure, CPP)16. Typically, cerebral autoregulation has been evaluated as a static or dynamic relationship between ABP (or CPP) and CBF17. The dynamic cerebral autoregulation assessment methods can be further classified into two major categories: (1) invoked autoregulation tests that require the application of specific maneuvers to induce changes in CBF following abrupt changes in ABP and (2) those that can be assessed on the basis of spontaneous fluctuations in the ABP during rest16.

The majority of the literature regarding the risk factors for CHS and hemodynamic changes after revascularization surgery have utilized radiological modalities such as computed tomography, positron emission tomography, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)9,12,18,19,20,21. These imaging modalities are inherently ‘snap-shot’ measures; furthermore, most of these studies have mainly investigated the changes in regional CBF following an operation. In contrast, transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD), can measure cerebral hemodynamics with excellent temporal resolution; the morphology of instantaneously induced changes in CBF velocity (CBFv) can be captured, from which meaningful autoregulatory parameters can be derived. Nevertheless, studies that explored the postoperative occurrence of CHS, using physiological signal derived autoregulatory parameters have rarely been conducted22,23,24,25. Given the nature of MMD patients with severe stenosis in intracranial major arteries, it may be more appropriate to assess dynamic cerebral autoregulation in maneuver-induced conditions to invoke an abrupt and more distinguishable hemodynamic change. Thus, parameters derived from both spontaneous fluctuations in resting conditions and invoked hemodynamic change conditions were employed to access autoregulatory function in MMD patients. We hypothesized that postoperative CHS is associated with impaired cerebral autoregulation and therefore, this study attempted to examine the changes in physiological signals and the associated autoregulation indices during the perioperative period, to determine the differences between the non-CHS and CHS groups, to find strong evidence regarding the pathogenesis of postoperative CHS and to use them in predicting, diagnosing, and managing postoperative CHS in patients with adult MMD.

Methods

Ethics statement

All procedures performed in this study, were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the declaration of Helsinki standards. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul National University Hospital (IRB no. 1712-029-904). All patients were informed of the experimental procedures and the potential risks, and written informed consent was obtained.

Study population

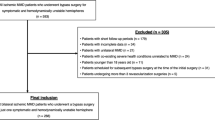

To ensure adequate statistical power, we initially aimed to collect data from 36 hemispheres in total. Among the adult MMD patients who were scheduled for combined bypass between December 2020 and January 2022, 26 hemispheres in 24 patients all of whom underwent consecutive combined bypass procedures performed by the experienced neurosurgeon (W.S.C.), were finally enrolled in this prospective study. Exclusions were made due to technical issues with TCD measurement (n = 7), patient discomfort preventing sustained measurement (n = 2) and loss of recorded data (n = 1) (Fig. 1). To determine this target sample size, a power analysis was performed using G*Power26version 3.1.9.7 to decide the sample size, using the mean and the standard deviation (SD) obtained from the previous literature27,28utilizing autoregulatory indices to investigate autoregulatory function in cerebrovascular disease cohort. Based on the previous literature, we estimated an effect size of 1.3 and the power analysis returned a sample size of 22 hemispheres, considering an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. We preliminarily determined to collect data from 36 hemispheres in total to account for the possibility of excluding data (e.g., technical problems, drop out). The inclusion criteria included the following: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) compatibility with the diagnostic criteria for MMD29; (3) intracerebral hemorrhage or recurrent ischemic symptoms, including transient ischemic attack and small cerebral infarction; (4) marked decrease in basal perfusion and reservoir capacity on brain SPECT and notable perfusion decrease and delay on brain arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI; and (5) no considerable medical history, such as traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, epilepsy, neuroinflammatory disease, metabolic encephalopathy, neurodegenerative disease, cardiovascular disease and other severe medical problems.

Flow chart of patient enrollment. Flow chart demonstrating the cohort selection. *One patient failed the initial monitoring at the first operation due to technical problems with TCD. However, the patient had a successful second monitoring at the second operation. TCD, transcranial Doppler ultrasound.

Surgical procedures

Combined bypass surgery was performed under general anesthesia with intravenous propofol and remifentanil. During the surgery, arterial PCO2 was maintained at a range of 35 to 40 mmHg, and mild hypothermia at a temperature level of 34 °C was induced. Systolic and mean blood pressures were basically maintained at around 120 and 85 mmHg, respectively4,8. However, the range of BP control was individualized according to the preoperative bedside BP and associated clinical symptoms. Direct [anastomosis between the superficial temporal artery and cortical middle cerebral artery (MCA) branch] and indirect (encephalo-duro-galeo-fascio-synangiosis) surgeries were combined for the revascularization procedure4,30. Detailed descriptions of the surgical procedure are provided in the supplementary material.

Evaluation and management of CHS

When postoperative CHS occurred, the patients were categorized into the “CHS group”, and the others were categorized into the “non-CHS group”. The diagnostic criteria of CHS were (1) focal hyperperfusion on brain SPECT and ASL MRI with no abnormal findings such as infarction and hemorrhage and (2) transient neurological deterioration corresponding well to the hyperperfused area4,12,21. Transient neurological symptoms generally include headache, motor weakness, sensory disturbance, language dysfunction, partial seizure, involuntary movement, and intracerebral hemorrhage. Seizure and involuntary movement were differentiated based on the electroencephalographic findings. Brain imaging, such as SPECT, CT, and MRI with diffusion-weighted, susceptibility-weighted or T2* gradient echo and ASL protocols, was selectively performed at the onset and end of CHS when the associated symptoms had almost entirely or completely improved. TCD was also conducted at the same time periods. The aforementioned key assessments for determining the diagnostic criteria for CHS were conducted by radiologists and/or neurologists, not specifically to differentiate CHS, but to identify the cause of new symptoms that emerged following surgery. To ensure inter-rater reliability in diagnosing CHS, the diagnosis was made with careful consideration, based on a consensus formed within the treating team through a comprehensive evaluation of the available information.

During the postoperative period, the patients were normohydrated, and their hemoglobin levels were kept between 10 and 11 g/dL. The mean ABP was maintained at the preoperative level ± 15 mmHg, with a systolic ABP less than 140 mmHg. Even after the diagnosis of CHS, the general principles for patient management were identical to those used in the immediate postoperative period, except that stricter blood pressure control was implemented and more precise management was adopted based on the patient’s symptoms and vital signs. Specifically, if CHS occurred, we implemented strict control by maintaining the mean ABP at preoperative level ± 10 mmHg, with a systolic ABP less than 130 mmHg. Other medications, such as edaravone, minocycline, steroids, and antiplatelet agents, were not newly administered due to insurance coverage policies in our country.

Neurophysiologic monitoring

TCD measurements were implemented bilaterally using 2 MHz transducer probes (Digi-one, Rimed Ltd, New York, USA) at an insonation level of 45–55 mm to record CBFv in the MCA. Both probes were firmly fixed in position throughout the experimental procedure with a headset we devised. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the CBFv recordings, the TCD measurements were conducted by N.H. and Y.C., both of whom are experienced neurosurgeons and skilled operators in this field. ABP was measured in the middle finger of the right hand held at heart level noninvasively and continuously using the volume-clamping method (Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Physiological signals were measured four times during the admission period according to the protocol: one day before the surgery (PRE1), within 24 h after the surgery (POD0), the third postoperative day (POD3) and on the discharge day (DD), among which the POD0 recordings were excluded from the evaluation, owing to insufficient data quality, as all the patients were unable to fully comply with the experimental protocol immediately after the major brain surgery. The time point for measuring physiological signals corresponding to DD was scheduled at POD10 in the non-CHS group; however, it varied slightly in the CHS group, with a median POD of 12.5 (range, POD 8–20), taking each individual patient’s improvements into account.

The experimental protocol began with a resting period of 10 to 15 min in a seated condition. Next, the patients performed a Valsalva maneuver (VM) by holding their breath for 30 s. The protocols were verbally instructed, while physiological signals were continuously monitored.

Data preprocessing and analysis

The ABP signals and the CBFv recordings were acquired at a sampling rate of 200 Hz and recorded for an off-line analysis. VM phase segmentation was accomplished based on the triggering information (i.e., taking a tidal breath, breath holding and exhaling period) and the general time trends of ABP during VM. The VM can be divided into 4 physiological phases, where the characteristics of each phase are as follows: (1) rise of ABP immediately after the onset of strain, (2) initial drop and partial recovery of ABP with sustained straining, (3) release of the strain with a sudden drop of ABP, and (4) overshoot and recovery of ABP to the baseline31,32,33. Baseline recordings were acquired 30 s before the VM, where ABP and both CBFv measured at ipsilateral (Ipsi) and contralateral (Contra) to the operation hemisphere were each averaged over the baseline period. Additionally, the CBFv laterality ratio was computed by the following formula:

Raw ABP and CBFv recordings were obtained at each of the four phases of the VM by averaging across each phase. The relative ABP and CBFv of each VM phase were calculated by subtracting the raw ABP and CBFv (Ipsi) obtained during the baseline period from the raw ABP and CBFv (Ipsi) obtained at each VM phase and were denoted as the relative ABP and relative CBFv.

To quantify the dynamic autoregulatory response, we utilized three indices: the Valsalva Maneuver Autoregulatory Index (VMAI) and mean flow index (Mxa), which are established measures, and the Valsalva Maneuver Overshooting Index (VMOI), which was first introduced in this study. The VMAI, which was first defined by Tiecks et al27,34,34., compares the ABP overshoot with CBFv (Ipsi) overshoot after release of the strain and is calculated by using the following formula:

Furthermore, to quantify the morphology of transient CBFv response during VM (i.e., overshoot), VMOI was calculated by the magnitude difference between the peak CBFv (Ipsi) during phase 4 of VM and the CBFv (Ipsi) measured at the corresponding point to the nadir of ABP during phase 3 of VM (Fig. 2A). Specifically, it was calculated as follows:

\(\:({X}_{1}=Time\:point\:where\:CBFv\:is\:at\:the\:peak\:point\:during\:VM\:Phase\:4)\)\(\:({X}_{2}=Time\:point\:where\:ABP\:is\:at\:the\:lowest\:point\:during\:VM\:Phase\:3)\)

Schematic description of the study procedure and representative cases of the CHS and non-CHS groups. (A) Illustration of the recordings (non-CHS patient) of ABP and CBFv signals obtained during the resting status (green box outline) and VM (blue box outline). (Mid left panel) Each shaded green box represents a 5-minute time window for calculating 30 consecutive 10-s averages of ABP and CBFv, obtained for deriving Mxa. (Mid right panel) Graph illustrating the general VM trends in each phase. The red point corresponds to the CBFv at the time when ABP is lowest during VM phase 3, and the green point corresponds to the peak CBFv point. The magnitude difference in CBFv between these two points was defined as VMOI. (B) Representative cases of spontaneous dynamic cerebral autoregulation in the non-CHS group. (The red line indicates the cut-off for discriminating against altered cerebral autoregulation). (C,D) Representative cases of maneuver associated dynamic cerebral autoregulation in the non-CHS group. (Shaded blue: Phase 4 of the VM where the notable overshooting phenomenon is presented) (E) Representative cases of spontaneous dynamic cerebral autoregulation in the CHS group. (F,G) Representative cases of maneuver associated dynamic cerebral autoregulation in the CHS group. (Shaded blue: Diminished overshooting phenomenon is presented). ABP, arterial blood pressure, CBFv, cerebral blood flow velocity, CHS, cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome, Mxa, mean flow index, VM, valsalva maneuver, VMOI, valsalva maneuver overshooting index.

Finally, Mxa, a time domain index first developed by Czosnyka et al36., was introduced to assess spontaneous dynamic cerebral autoregulation. Mxa represents the stability of CBF during changes in CPP or ABP, where a negative or lack of correlation between ABP and CBFv indicates functional autoregulation37. For the ABP and CBFv (Ipsi) signals, 10-s averages were calculated using recordings obtained during the resting state (i.e., recordings before the beginning of the VM protocol). Then, 30 consecutive 10-s averages of ABP and CBFv (Ipsi) were used to calculate a single Pearson’s correlation coefficient, where the computations were repeated with a 5-min moving window every 10 s as previously reported38,39. An overview of the autoregulation indices derived from the physiological recordings during a single trial of resting state and VM is presented in Fig. 2A. The aforementioned recordings and variables were averaged over two repeated trials with few exceptions of using single trial values (e.g., the patient did not complete the VM).

A comprehensive analysis was performed using a logistic regression model to find the relation of the multiple autoregulation indices (i.e., VMAI, VMOI and Mxa) to CHS occurrence in all the available recordings along the longitudinal time axis. For the evaluation, a 5 × 5 stratified k-fold cross-validation was employed, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was determined. The model using the PRE1 autoregulation indices as input variables was further interpreted using a Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) value analysis40. Feature importance was derived by calculating the effect of a feature on the model, enabling better interpretation of the results of the logistic regression model. All data preprocessing and analysis were performed using MATLAB (R2021a; Mathworks, Natick, USA) and Python 3.8.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data are presented as medians with ranges or counts (%), as appropriate. All other data are reported as medians with interquartile ranges. To calculate the differences between the CHS and non-CHS groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used (For certain categorical demographic characteristics, Fisher’s exact test was applied). To determine the optimal cut-off value of the PRE1 autoregulation indices for discriminating between the CHS and non-CHS groups, an AUC analysis with Youden’s J statistic (sensitivity + specificity − 1) was performed. Wilcoxon signed t-tests were applied to examine the longitudinal change (i.e., from PRE1 to DD). Within the VM, phase-wise differences of recordings were explored by using the Friedman test. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyze longitudinal differences (i.e., from PRE1 to DD) in the AUC derived from the logistic regression model. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package version 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics and clinical course of CHS

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 30 years (range 24–37 years), and females were dominant (n = 20, 83.3%). Unilateral MMD was identified in four patients (16.7%). Except for one case of hemorrhagic MMD, all patients initially presented with ischemic symptoms. In addition, other postoperative complications included transient symptomatic focal infarction in two patients, permanent symptomatic focal infarction in one patient, and pulmonary thromboembolism in one patient.

Out of 26 hemispheres in 24 patients, 12 patients (13 hemispheres) experienced postoperative CHS. In two patients who underwent revascularization surgery twice, one patient developed postoperative CHS after both bypass surgeries at an interval of 6 months. The other experienced CHS only after the first bypass. Postoperative CHS occurred at a median POD of 6 (range, POD 1–9) and was maintained for a median of 6.5 days (range, 2–15 days). Clinical symptoms included contralateral sensory disturbance in 100%, contralateral motor weakness in 76.9%, language dysfunction in 46.2%, and others such as involuntary movement in one patient, headache in one, subarachnoid hemorrhage in one and agraphia in one. Most of the sensory disturbance and motor weakness were present in the arm, hand and face.

Comparison of the physiological parameters between CHS and non-CHS groups

Representative recordings of the physiological signals (i.e., ABP and CBFv) during the VM and physiological signal derived autoregulation indices are shown in Fig. 2B–G. The observed trend of ABP and CBFv signals during each VM phase in the non-CHS group is consistent with previous studies (Fig. 2C,D)31,32,33. Evident VM trends are shown in both relative ABP and relative CBFv (with respect to the baseline measurements) with the elimination of individual variability (Fig. 3). VM phase-wise differences in both ABP and CBFv were present in all the available recordings at PRE1, POD3 and DD (P < 0.001). The median values of the relative CBFv (VM phase 4) before the operation were 4.616 and 0.589 cm/s in the non-CHS and CHS groups, respectively (P = 0.016). Similarly, a difference in the relative CBFv (VM phase 4) was noted in the POD3 recordings (median: 6.730 in the non-CHS group versus 3.669 cm/s in the CHS group; P = 0.041), where blunted overshoot could be expected in the CHS group. However, these differences in the relative CBFv (VM phase 4) were not shown in the DD recordings (P = 0.591).

Baseline data (ABP, CBFv, CBFv laterality ratio) before the VM were also explored to find the association between the presence of CHS and physiological parameters (Table 2). The ABP and CBFv measured from both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres did not differ between the non-CHS and CHS groups. The CBFv laterality ratio measured after the operation, however, showed significant differences between the non-CHS and CHS groups (P = 0.037 and 0.018 for POD3 and DD, respectively).

Comparison of the autoregulation indices between the CHS and non-CHS groups

The differences between the CHS and non-CHS groups in terms of the autoregulation indices are summarized in Table 2. The VMAI values were statistically insignificant during the perioperative period. VMOI measured at PRE1 and POD3 was significantly lower in the CHS group (P = 0.001 and 0.029, respectively). However, VMOI measured at DD became statistically insignificant (P = 0.270). Mxa measured at PRE1 was insignificant between the groups; however, Mxa measured at POD3 and DD was higher in the CHS group (P = 0.020 and 0.023, respectively). Additionally, the autoregulation indices derived using CBFv (Contra) did not differed between the CHS and non-CHS groups during the perioperative period.

Longitudinal changes in the autoregulation indices

The changes in the autoregulation indices over time (i.e., from PRE1 to DD) are shown in Fig. 4. In the CHS group, the median VMAI changed from 0.952 to 0.978 and to 0.973 toward the DD [P = 0.004 (PRE1 - POD3), 0.476 (POD3 – DD) and 0.034 (PRE1 – DD)]. VMOI tended to increase over time, with median values of 12.345, 15.819 and 20.640 cm/s [P = 0.021 (PRE1 - POD3), 0.004 (POD3 – DD) and 0.001 (PRE1 – DD)]. In the CHS group, significant differences over time were not found in the Mxa, where the median value increased on POD3 from 0.205 to 0.318 and then decreased on the DD to 0.315 [P = 0.173 (PRE1 - POD3), 0.426 (POD3 – DD) and 0.217 (PRE1 – DD)]. In the non-CHS group, Mxa gradually decreased along the time axis [median 0.238, 0.181 and 0.077; P = 0.570 (PRE1 - POD3), 0.191 (POD3 – DD) and 0.036 (PRE1 – DD)].

A comprehensive analysis was conducted using a logistic regression model with multiple cerebral autoregulation indices, and the AUC score for differentiating the CHS and non-CHS groups is shown in Fig. 5. The median AUC scores of the logistic regression model when using three features (i.e., VMAI, VMOI and Mxa) were 0.889, 0.778 and 0.667 for PRE1, POD3 and DD, respectively [P = 0.674 (PRE1 – POD3), 0.001 (POD3 – DD) and 0.001 (PRE1 – DD)]. It can be inferred that the difference between the CHS and non-CHS groups decreases as the median AUC score decreases over time.

Preoperative autoregulation indices for predicting CHS

Based on an AUC analysis with Youden’s J statistic, the optimal cut-off values of the PRE1 autoregulation indices for distinguishing the CHS and non-CHS groups were determined (Fig. 6A). VMOI had an AUC of 0.838 (0.684–0.992) with a Youden index of 14.762 cm/s for differentiating the two groups. Similarly, AUCs of 0.676 (0.479–0.873) and 0.557 (0.338–0.776) with a Youden index of 0.994 (a.u.) and 0.181 (a.u.) were found for VMAI and Mxa, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 6A). In addition to a single inspection of each autoregulation index, feature importance and SHAP value were discovered to further interpret the derived PRE1 AUC score of the logistic regression model. The VMOI was found to be the most critical feature, and the SHAP value indicates that low values of VMOI contribute positively to CHS prediction, meaning that the patients from the CHS group have a lower value of VMOI than the patients from the non-CHS group (Fig. 6B,C). Similar but less distinct distributions of SHAP values were observed in VMAI with a lower feature importance than that of VMOI. Mxa had the least impact on the performance of the logistic regression model with the blurred distribution of the SHAP value, and these results are in line with the probability value obtained from the conventional statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis and logistic regression model interpretation of PRE1 recordings. (A) ROC curves of the three autoregulation indices (VMOI, VMAI, Mxa) for the differentiation of the CHS and non-CHS groups (the best cut-off points that are equivalent to measuring the J of Youden Index are marked along with the false positive rate and true positive rate corresponding to the cut-off points). (B) Feature importance of the logistic regression model. (C) SHAP value of the logistic regression model.

Discussion

Impaired autoregulation has long been thought to be the primary pathophysiology for the occurrence of CHS. Evidence supporting this claim has been occasionally presented in imaging and neurophysiology studies9,12,18,19,20,21,41. There have been only a few studies22,23 that have examined the incidence of CHS following bypass surgery in patients with MMD, solely using physiological signals. Therefore, the following research objectives were established to validate this claim. We (1) examined hemodynamic differences between the non-CHS and CHS groups, (2) evaluated postoperative changes in autoregulation indices derived from ABP and CBFv recordings, and (3) investigated the potential of preoperative autoregulation indices for predicting CHS before revascularization. The autoregulatory function was measured in MMD patients perioperatively, using autoregulation parameters derived from both spontaneous and maneuver-induced condition. Before the operation, a higher VMOI value was observed in the non-CHS group than in the CHS group, suggesting that the autoregulation function of the non-CHS group was superior to that of the CHS group. These findings were similarly observed at POD3, while the differences were not present at DD. With the exception of PRE1, Mxa was significantly higher in the CHS group than in the non-CHS group, indicating that the CHS group had worse autoregulation ability. A recovery of autoregulatory function was observed in the CHS group based on the results of VMAI and VMOI. In light of these findings, it is evident that patients experiencing postoperative CHS possess a diminished level of autoregulatory function. Additionally, among the different autoregulatory indices, VMOI was the most potent predictor of postoperative CHS.

Incidence of CHS after revascularization procedure

The occurrence of postoperative CHS at our center, Seoul National University Hospital, is higher than typically reported, as documented in our earlier publications4,42. This may be attributed to several factors: (1) surgeries at our institution primarily involve unstable patients with hemodynamic instability and recurrent or progressive TIA or cerebral infarctions, (2) most patients are in advanced stages of Moyamoya disease (Suzuki grades 4–5), and (3) all bypass procedures specifically targeted recipient arteries supplying eloquent brain regions, which inherently increases the risk of postoperative CHS.

Hemodynamic differences between CHS and non-CHS

In this study, postoperative ABP and CBFv on the operated hemisphere measured before the VM did not differ significantly between the groups with and without CHS. Existing literature also states that the presence of CHS after revascularization surgery may not necessarily be associated with an increase in CBF or CBFv43,44. However, the relative CBFv (with respect to the baseline measurements) during phase 4 of the VM revealed a severely reduced overshoot in patients with postoperative CHS. This event of overshooting during VM (phase 4) for other medical conditions is documented in a few other studies27,45; however, this phenomenon is approximated by simply taking into account the mean CBFv during VM (phase 4). Hence, we defined VMOI to quantify this phenomenon during VM (phase 4), based on the magnitude change in CBFv after the release of the strain. Besides the VM, there are other non-pharmacological approaches used for measuring dynamic cerebral autoregulation, such as the transient hyperemic response test (THRT)46. This test measures the response of the CBFv to brief (5-sec) compression of the carotid artery47. The mechanism of VMOI can be explained in a similar manner to that of THRT, as the CBFv overshooting action after the release of the strain is assessed. This suggests that a higher value of VMOI may be a clinical indicator of intact cerebral autoregulation, which is consistent with our findings that the non-CHS group has a higher VMOI value than the CHS group. The ‘Mxa’ has been reported to be an effective index for assessing cerebral autoregulation in a variety of studies involving different types of medical conditions39,48. In the present study, the level of Mxa varied according to whether CHS took place after the operation, where reduced cerebral autoregulation denoted as a higher value of Mxa, was associated with the development of CHS. MMD patients who are required to have bypass surgery have severe stenosis in the intracranial arteries. Therefore, in the context of assessing autoregulatory function in MMD, parameters such as VMOI, which measures autoregulatory function based on extreme and excessive hemodynamic changes, should be utilized in conjunction with autoregulatory parameters derived from spontaneous conditions with subtle hemodynamic changes.

Recovery of cerebral autoregulatory function after surgery

There is evidence that cerebral autoregulation is affected by revascularization surgery, and previous reports indicate that the process of stabilizing and recovering autoregulatory function may take some time49,50. Therefore, in this study, the longitudinal change in the various cerebral autoregulation parameters after the operation was further investigated. Our results show that this longitudinal change was particularly pronounced in patients with postoperative CHS. Moreover, the comprehensive analysis using a logistic regression model demonstrated that the autoregulatory function in the CHS group tended to become comparable to that in the non-CHS group over time. Under the assumption that the autoregulatory function in the non-CHS group remained relatively intact although normal autoregulatory function in the normal control was not included, we can conclude that the autoregulatory function in the CHS group recovered to a similar status as cerebral autoregulation in the non-CHS group over time.

Prognostic value for postoperative management of CHS

Identifying patients who may be at risk of developing postoperative CHS is essential, as early detection would help them to cope with significant complications51. In this study, we sought to determine the prognostic value of cerebral autoregulation indices before bypass surgery. In previous studies39,52, the cut-off value for Mxa discriminating altered cerebral autoregulation was 0.3 (a.u.); however, in the present study, the optimal cut-off value for Mxa was determined to be 0.181 (a.u.). The threshold for determining intact cerebral autoregulation can vary depending on the targeted clinical status and methodological approach used for calculating Mxa53. Previous studies regarding autoregulatory function have typically focused on survival versus death or mild versus severe neurological status in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. However, we targeted the occurrence of postoperative CHS, which would be determined on the better range of autoregulatory function. Similarly, for VMAI, the threshold for discriminating between the two groups was 0.994 (a.u.) in this study, whereas previous studies reported that the threshold for distinguishing dysfunction in autoregulation from intact autoregulation was 1.000 (a.u.)27,34 Lastly, the discrimination threshold of VMOI between the CHS and non-CHS groups was 14.762 cm/s. Since the quantified index capturing the actual magnitude change of an overshooting event is first introduced in this study, its usefulness should be clarified in future studies utilizing this index. These three indices associated with autoregulatory function are expected to be used prior to surgery as prognostic values of the occurrence of postoperative CHS.

Limitations

The present study has the following limitations. First, this was a single institution study with a limited number of participants. To advance the understanding of these autoregulatory indices and their clinical applicability, future research should aim to employ a larger and more sufficient sample size. Additionally, it would be beneficial to compare the proposed metric, VMOI, with established markers such as VMAI and Mxa in healthy subjects to assess its reflection of cerebral autoregulation and its relationship with traditional metrics. Second, extended research with consideration of multiple factors (e.g., baroreceptor-reflex breakdown, axon-like trigeminovascular reflex) other than autoregulation indices that may contribute to postoperative CHS development will be needed14. Third, when performing statistical comparisons, the samples from each group must be independent and randomly distributed. Therefore, when including both hemispheres in the analysis, generalized estimation equation (GEE) analysis is typically employed. However, since only two patients underwent bilateral surgeries in this study, GEE was not applied in this study. In future studies, if we include more subjects with bilateral surgeries, we plan to utilize the GEE method to account for this. Forth, the DD recordings used in this study varied, especially in the CHS group, in which some patients completely recovered from postoperative CHS at discharge, and the others were discharged with mild but residual symptoms. It might be more appropriate to evaluate the patients based on the recordings obtained on the same day as well as the recordings at discharge when the CHS related symptoms had completely disappeared. Lastly, the increased thoracic pressure during the VM could potentially reduce venous outflow, which could, in turn, diminish arterial inflow. In patients with MMD, who already have compromised cerebral vasculature, this reduction in arterial inflow could further exacerbate ischemia. To account for these considerations, future studies involving VM in MMD patients may include venous outflow measurements.

Conclusion

CHS is one of the serious complications after direct bypass surgery in patients with adult MMD. Its development has long been thought to be related to impairment of cerebral autoregulation; however, this has rarely been proven. This study demonstrated that impaired cerebral autoregulation seems to be the main pathophysiology of postoperative CHS. Autoregulation indices based on physiological signals was effective in evaluating cerebral autoregulatory function during the perioperative period and in predicting the postoperative CHS in a high likelihood. Further studies are expected to validate the usefulness of autoregulation indices as a sensitive indicator of the occurrence of postoperative CHS.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

Suzuki, J. & Kodama, N. Moyamoya disease—a review. Stroke 14, 104–109 (1983).

Kim, S. K. et al. Pediatric Moyamoya disease: An analysis of 410 consecutive cases. Ann. Neurol. 68, 92–101 (2010).

Kim, T., Oh, C. W., Bang, J. S., Kim, J. E. & Cho, W. S. Moyamoya disease: Treatment and outcomes. J. Stroke 18, 21–30 (2016).

Cho, W. S. et al. Long-term outcomes after combined revascularization surgery in adult moyamoya disease. Stroke. 45, 3025–3031 (2014).

Takahashi, J. C. et al. Significance of the hemorrhagic site for recurrent bleeding: prespecified analysis in the Japan Adult Moyamoya Trial. Stroke. 47, 37–43 (2016).

Scott, R. M. & Smith, E. R. Moyamoya disease and Moyamoya syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1226–1237 (2009).

Houkin, K., Kamiyama, H., Takahashi, A., Kuroda, S. & Abe, H. Combined revascularization surgery for childhood moyamoya disease: STA-MCA and encephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 13, 24–29 (1997).

Fujimura, M. & Tominaga, T. Significance of cerebral blood flow analysis in the acute stage after revascularization surgery for moyamoya disease. Neurol. Med. -Chir. 55, 775–781 (2015).

Cho, W-S. et al. Symptomatic cerebral hyperperfusion on SPECT after indirect revascularization surgery for Moyamoya disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 38, 44–46 (2013).

Phi, J. H. et al. Postoperative transient neurologic dysfunction: a proposal for pathophysiology. J. Clin. Neurol. 14, 393–400 (2018).

Fujimura, M. et al. Significance of focal cerebral hyperperfusion as a cause of transient neurologic deterioration after extracranial-intracranial bypass for moyamoya disease: comparative study with non-moyamoya patients using N-isopropyl-p-[123I] iodoamphetamine single-photon emission computed tomography. Neurosurgery. 68, 957–965 (2011).

Kim, J. E. et al. Transient hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery/middle cerebral artery bypass surgery as a possible cause of postoperative transient neurological deterioration. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 25, 580–586 (2008).

Uchino, H. et al. Predictors and clinical features of postoperative hyperperfusion after surgical revascularization for moyamoya disease: a serial single photon emission CT/positron emission tomography study. Stroke. 43, 2610–2616 (2012).

van Mook, W. N. K. A. et al. Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 4, 877–888 (2005).

Lin, Y-H. & Liu, H-M. Update on cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 12, 788–793 (2020).

Azevedo, E. & Castro, P. Cerebral Autoregulation. 215–227 (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Tiecks, F. P., Lam, A. M., Aaslid, R. & Newell, D. W. Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke. 26, 1014–1019 (1995).

Wang, D. et al. Predicting cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome following superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery bypass based on intraoperative perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–10 (2015).

Chang, C. H. et al. The role of perfusion computed tomography in the prediction of cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome. PLoS One. 6, e19886 (2011).

Sato, S. et al. Preoperatively reduced cerebrovascular contractile reactivity to hypocapnia by hyperventilation is associated with cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome after arterial bypass surgery for adult patients with cerebral misery perfusion due to ischemic moyamoya disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 38, 1021–1031 (2018).

Fujimura, M., Kaneta, T., Mugikura, S., Shimizu, H. & Tominaga, T. Temporary neurologic deterioration due to cerebral hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery anastomosis in patients with adult-onset moyamoya disease. Surg. Neurol. 67, 273–282 (2007).

Lee, J. K., Williams, M., Reyes, M. & Ahn, E. S. Cerebrovascular blood pressure autoregulation monitoring and postoperative transient ischemic attack in pediatric moyamoya vasculopathy. Paediatr. Anaesth. 28, 94–102 (2018).

Lee, J. K. et al. Cerebrovascular autoregulation in pediatric moyamoya disease. Paediatr. Anaesth. 23, 547–556 (2013).

Chen, J. et al. Impaired dynamic cerebral autoregulation in moyamoya disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 19, 638–640 (2013).

Horn, P. et al. Hemodynamic reserve and high-intensity transient signals in moyamoya disease. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 19, 141–146 (2005).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A-G., Buchner, A. & G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191 (2007).

Tiecks, F. P., Douville, C., Byrd, S., Lam, A. M. & Newell, D. W. Evaluation of impaired cerebral autoregulation by the valsalva maneuver. Stroke. 27, 1177–1182 (1996).

Calviere, L. et al. Prediction of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage using cerebral blood flow velocities and cerebral autoregulation assessment. Neurocrit. Care. 23, 253–258 29.

Fujimura M, et al. 2021 Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Moyamoya Disease: Guidelines from the Research Committee on Moyamoya Disease and Japan Stroke Society. Neurol. Med.-Chir. 62, 165–170 (2022). (2015).

Newell, D. W., Vilela, M. D., Sekhar, L. N., Tabrizi, P. & Spetzler, R. F. Superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery bypass. Neurosurgery. 54, 1441–1449 (2004).

Pstras, L., Thomaseth, K., Waniewski, J., Balzani, I. & Bellavere, F. The Valsalva manoeuvre: physiology and clinical examples. Acta Physiol. 217, 103–119 (2016).

Perry, B. G., Cotter, J. D., Mejuto, G., Mündel, T. & Lucas, S. J. E. Cerebral hemodynamics during graded valsalva maneuvers. Front. Physiol. 5, 349 (2014).

Goldberg, H., Elisberg, E. I. & Katz, L. N. The effects of the Valsalva-like Maneuver upon the circulation in normal individuals and patients with mitral stenosis. Circulation. 5, 38–47 (1952).

Bellapart, J. & Fraser, J. F. Transcranial Doppler Assessment of Cerebral Autoregulation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 35, 883–893 (2009).

Tiecks, F. P. et al. Effects of the valsalva maneuver on cerebral circulation in healthy adults: a transcranial doppler study. Stroke. 26, 1386–1392 (1995).

Czosnyka, M., Brady, K., Reinhard, M., Smielewski, P. & Steiner, L. A. Monitoring of cerebrovascular autoregulation: facts, myths, and missing links. Neurocrit Care. 10, 373–386 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Comparison of frequency and time domain methods of assessment of cerebral autoregulation in traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35, 248–256 (2015).

Budohoski, K. P. et al. Monitoring cerebral autoregulation after head injury. Which component of transcranial doppler flow velocity is optimal? Neurocrit Care. 17, 211–218 (2012).

Sorrentino, E. et al. Critical thresholds for transcranial doppler indices of cerebral autoregulation in traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 14, 188–193 (2011).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Neural Information Processing Systems. 4768–4777 (2017).

Ogasawara, K. et al. Prediction and monitoring of cerebral hyperperfusion after carotid endarterectomy by using single-photon emission computerized tomography scanning. J. Neurosurg. 99, 504–510 (2003).

Lee, K. et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption imaging in postoperative cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome using DCE-MRI. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 44, 345–354 (2005).

Karapanayiotides T, et al. Postcarotid endarterectomy hyperperfusion or reperfusion syndrome. Stroke. 36, 21–26 (2005). (2024).

Buczek, J., Karliński, M., Kobayashi, A., Białek, P. & Członkowska, A. Hyperperfusion syndrome after carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 35, 531–537 (2013).

Zhang, R., Crandall, C. G. & Levine, B. D. Cerebral hemodynamics during the Valsalva Maneuver: insights from Ganglionic Blockade. Stroke. 35, 843–847 (2004).

Topcuoglu, M. A. Transcranial doppler ultrasound in neurovascular diseases: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. J. Neurochem. 123, 39–51 (2012).

Smielewski, P., Czosnyka, M., Kirkpatrick, P. & Pickard, J. D. Evaluation of the transient hyperemic response test in head-injured patients. J. Neurosurg. 86, 773–778 (1997).

Crippa, I. A. et al. Impaired cerebral autoregulation is associated with brain dysfunction in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care. 22, 1–9 (2018).

Magee, T. R., Davies, A. H., Baird, R. N. & Horrocks, M. Transcranial Doppler measurement before and after carotid endarterectomy. J. R Coll. Surg. Edinb. 37, 311–312 (1992).

Reinhard, M. et al. Effect of carotid endarterectomy or stenting on impairment of dynamic cerebral autoregulation. Stroke. 35, 1381–1387 (2004).

Dalman, J. E., Beenakkers, I. C. M., Moll, F. L., Leusink, J. A. & Ackerstaff, R. G. A. Transcranial doppler monitoring during carotid endarterectomy helps to identify patients at risk of postoperative hyperperfusion. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 18, 222–227 (1999).

Crippa, I. A. et al. Cerebral autoregulation in anoxic brain injury patients treated with targeted temperature management. J. Intensive Care. 9, 1–9 (2021).

Olsen, M. H., Riberholt, C. G., Plovsing, R. R., Møller, K. & Berg, R. M. G. Reliability of the mean flow index (Mx) for assessing cerebral autoregulation in healthy volunteers. PHYSIOL. REP. 9, e14923 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: HI17C1561); and a Grant number 0420210280 from the SNUH Research Fund; and by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (Grant number: 2022R1A2C1013205); and by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (grant number: RS-2024-00336744).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W-S.C., D-J.K., J.K., K.K., and J.K. contributed to the conception and design of the study; J.K., N.H., Y.C., H.L., E.H., S.L., and S.L. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; and W-S.C., D-J.K., J.K., H.K., and J.K. contributed to interpretation of data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.H., Hong, N., Kim, H. et al. Autoregulatory dysfunction in adult Moyamoya disease with cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome after bypass surgery. Sci Rep 14, 26451 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76559-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76559-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Postoperative seizure, stroke, hemorrhage, and cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome rates in adult patients with moyamoya disease undergoing revascularization: a systematic review and proportional meta-analysis

Neurosurgical Review (2026)

-

Incidence of cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome following revascularization surgery in moyamoya patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Neurosurgical Review (2025)