Abstract

Several indices have been devised to quantify a person’s stability from its gait pattern during overground walking. However, clinical interpretation of the indices is difficult because the link between being stable and adopting a mechanically stable gait pattern may not be straightforward. This is particularly true for one of these indices, the margin of stability, for which opposite interpretations are available in the literature. We collected overground walking data in two groups of 20 children, with unilateral cerebral palsy (CP) and typically developing (TD), for two conditions, on flat and on uneven grounds (UG). We postulated that TD children were more stable during gait than children with CP and that both groups were more stable on flat compared to UG. We explored the coherent association between several indices and the two postulates to clarify clinical interpretation. Our results showed that increased margin of stability, increased amplitude of the whole-body angular momentum, decreased duration of single limb support, increased variability (gait kinematics, step length, and step width) were associated with reduced stability for both postulates. However, results for the margin of stability were paradoxical between the sides in the CP group where small margin of stability was indicative of a fall forward strategy on the affected side rather than improved stability. Whole-body angular momentum and duration of single limb support appeared as the most sensitive indices. However, walking speed influenced these and would need to be considered when comparing groups of different walking speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In ambulant children with cerebral palsy, three-dimensional gait analysis provides an objective assessment of the walking function to plan orthopaedic treatments, and evaluate the effect of these1. Questions about stability during gait often arise during clinical interpretation. For example, clinicians may wonder if a treatment, or the use of an orthotic device, may improve or reduce stability during gait.

Clinical interpretation focuses on the walking person, i.e. answering the question: “Is John stable?”, or “Is John more or less stable after receiving a treatment?”. In these questions, what is meant by “being stable or being unstable” is difficult to qualify objectively. Often, we aim to know whether the person feels confident and is competent at maintaining balance during walking. We expect that persons confident and competent at maintaining balance during walking will translate into being at low, or conversely high, risk of falling during gait. However, dynamic stability of the person is not measured per se but inferred from surrogate indices calculated based on the gait pattern2.

The equivalence between “being stable” and “adopting a stable gait pattern” is often assumed rather than tested. In principle, the association between adopting a stable gait pattern, as measured by the index, and being stable should be tested against an external criteria such as history of falls, capacity to recover balance after large external perturbation, or capacity to walk on a range of terrain, but it is rarely the case for practical reasons2. This may lead to results appearing paradoxical, as was noted recently for the margin of stability3.

The margin of stability (MoS) was introduced by Hof as a measure of how far a gait pattern may be from the limits of dynamical stability4. It uses an inverted pendulum model of the human body during gait to assess dynamic stability in the sagittal and frontal planes4. The MoS is the distance between the projection of the extended centre of mass (xCoM) and the border of the feet as the basis of support3,4. Negative MoS denotes mechanically unstable situations which would lead to falling if no correcting actions or steps were taking place5. Increasingly positive MoS denotes increasingly stable mechanical situations.

A common a priori interpretation of the MoS is that unstable persons adopt unstable gait patterns. However, several studies noted increased MoS, hence a more stable pattern from the point of view of the MoS, in populations with walking difficulties and higher risk of falling, including children with cerebral palsy3,6,7,8. Recently, Kazanski et al. devised a complex new index that incorporates step to step variability to the MoS to solve this so-called paradox6. However, the paradox may be to assume that stable persons adopt stable gait pattern as measured with the MoS when the opposite relationship may in fact be true, i.e. that stable persons can afford more unstable gait pattern while unstable persons need to adopt more stable gait pattern. For example, infants who have just acquired independent walking adopt a wide stance during walking, hence a large and positive medio-lateral MoS, and MoS tend to decrease with maturation of motor control9,10,11. In addition, other researchers adopt the opposite a priori interpretation of the MoS. In their study, Wist et al. interpreted an increased MoS during dual tasks (walking + cognitive tasks) as a sign of impaired stability12.

In addition to the MoS, a range of indices of stability may be obtained during routine clinical gait analysis, i.e. overground walking, where a relatively small number of non-consecutive gait cycles are collected. The whole-body angular momentum (WBAM) measures the contribution of body segments to the angular momentum around the centre of mass (CoM). Several studies have shown that the WBAM is tightly regulated and kept small during normal walking, through cancellation of the contribution between segments13,14. In contrast, the range of WBAM was increased in population and in situation with higher likelihood of falling15,16,17 or with decreased postural balance as measured with the Berg balance scale8.

Variability of the gait pattern and stability of the person adopting the gait pattern may be linked, although variability and stability are two different concepts2. Indices based on the variability of spatio-temporal parameters have been used extensively in the past, notably stride or step width variability18,19,20. Recently, gait kinematics variability has been shown to decrease with age in typically developing children up to 16 years of age and to remain constant in young adults after that21,22. Hence, kinematics variability may be a sensitive measure of motor control maturation, and linked to how competent a subject is for a given dynamic task.

Gage and Perry proposed the five pre-requisites of normal gait as key clinical concepts to appraise gait impairments23,24. The first of these pre-requisites is “stability in stance”. Within the stance phase, balance is particularly challenged during single limb support, when only one foot is in contact with the ground to allow the other foot to swing through. During normal gait, single limb support phase is about 40% of the gait cycle with moderate change with walking speed, from 32% at very slow walking speed to 42% at very fast walking speed25. In line with recent findings26, we hypothesized that a reduction of the duration of single limb support expressed as a percentage of the gait cycle, after controlling for the effect of walking speed, would be related to impaired stability.

In this study, we proposed to clarify the interpretation of the MoS as an index of stability. The study is based on a secondary analysis of the data presented by Romkes et al.27 who collected overground walking in two groups of children, typically developing (TD) and children with cerebral palsy (CP), and for two conditions, the hard and flat ground of the gait laboratory (flat) and uneven ground (UG) made of shock absorbing material. We postulated that (1) TD children are more stable during walking than children with CP for the same age, and that (2) both groups are less stable on UG compared to flat ground. We tested the sign and consistency of the association with the two postulates, held as true.

The two postulates are strongly supported by evidence. Children with CP are at higher risk of falls than TD peers28, they show larger postural sway during static standing29,30, and adults with CP have about four times larger risk of falls than adults without CP31,32. Similarly, walking on uneven ground is associated with increased risk of falling and is perceived as a more challenging walking condition33,34,35,36.

We hypothesized that MoS would be larger for children with CP, and larger for both groups when walking on UG. We hypothesized that the range of WBAM and all indices based on variability would also be larger for the same comparisons.

Materials and methods

The readers are referred to the original publication of Romkes et al. for detailed information about the participants and the data collection process27. In short, 20 TD children (mean age: 11.4 years range: [7.7–16.7]) and 20 children with unilateral CP (gross motor function classification I and II, mean age: 10.8 years range: [8.3–17.8]) participated in the study. Data collection took place in the gait laboratory at the University children’s hospital Basel (UKBB, Switzerland). The study was conducted according to all relevant guidelines and regulations. It was approved by the local ethical committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, EKNZ, #2015-300) and all subjects, or their parent or legal guardian if under the age of 14 years, signed a written informed consent.

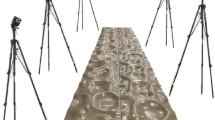

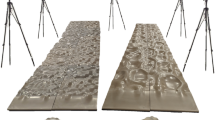

All children walked barefoot for a minimum of 6m for two conditions: (1) directly on the floor of the gait laboratory, a hard and flat surface, and (2) on compliant uneven ground terrain made from Terrasensa (Hübner GmbH, Germany) 50 × 50 × 4–8 cm tiles, Fig. 1. The order of the two conditions was randomly selected for each child.

Picture with 3D overlay of the set-up with one child with unilateral cerebral palsy. Coronal view for the flat surface condition (left picture), sagittal view for the uneven ground condition for the affected side (middle picture), and the sound side (right picture). The centre of mass (CoM), the extended CoM (xCoM), and the markers utilised as the boundary of the basis of support for the lateral MoS (left, DMT5) and the anterior MoS (middle and right, TOE) are outlined in blue.

Full body kinematics data for 10 gait cycles per side were included for analysis. Full body dynamics necessary for the MoS and WBAM calculations was obtained from the kinematics of the conventional gait model (CGM 1.0 via Plug in Gait, Vicon Nexus, UK37) with the body segment inertial parameters (including reference points and lengths) from Dumas et al.38. The position of the overall body centre of mass (CoM) was calculated as the weighted average of each body segment CoMs. The overall body extended centre of mass (xCoM) position was calculated according to Hof4. The equivalent pendulum length (\(eL\)) was calculated as the average distance over the gait cycle between the ipsilateral ankle joint centre and the CoM. The positive direction of walking was calculated as the vector from the first to the last position of the CoM during the gait cycle. The medio-lateral direction of walking was calculated as the vector perpendicular to the positive direction of walking in the transverse plane of the laboratory, i.e. perpendicular to the vertical axis.

The anterior MoS was calculated as the distance along the positive direction of walking between xCoM and the marker located on the ipsilateral foot second metatarsal head (TOE). The lateral MoS was calculated as the distance along the medio-lateral direction of walking between xCoM and the ipsilateral foot fifth metatarsal head marker (DMT5, located superior to the metatarsal head). The MoSs were reported at heel strike with a positive value indicating a stable mechanical situation, i.e. the xCoM was located more posterior and more medial than the corresponding foot markers for the anterior, respectively lateral, MoS3.

The WBAM was calculated as the sum of each body segment momenta with respect to the CoM, e.g.13,14,39 and scaled to body size using the equivalent pendulum length (eL) as characteristic length. Non-dimensional \(WBAM=\frac{WBAM}{body mass\times eL\times \surd \left(eL\times 9.81\right)}\)40,41. The amplitude of non-dimensional WBAM over the gait cycle was reported in the sagittal (positive direction of walking x vertical), coronal (medio-lateral direction of walking x vertical), and transverse (positive x medio-lateral direction of walking) planes.

Spatio-temporal parameters were calculated from the foot marker positions at foot contact and foot off events from both sides42. Single limb support was defined as the period during stance between the opposite foot off and opposite foot contact events. Stride width was calculated as the distance between the contralateral foot position at foot contact and its projection onto the vector joining the position of the ipsilateral foot at the start and end of the gait cycle (ipsilateral foot contact events). Step length was calculated as the distance along the positive direction of walking between the ipsilateral foot contact at the end of the gait cycle (i.e. second foot contact) and the contralateral foot position at foot contact. It is important to note that gait nomenclature specifies a left stride is composed of a right step first and a left step second, and vice versa for the right side. All spatio-temporal parameters were scaled to body size using leg length and the formulae from Hof40. Leg length was measured with a tape measure in standing, between the ipsilateral anterior iliac spine and medial ankle malleolus bony landmarks.

Stride width and step length variability were reported with the standard deviation (SD) over 10 cycles for each subject, side, and condition. The GaitSD was used to summarise the variability of lower limb kinematics during gait21. The most representative cycle was selected automatically and used for the anterior and lateral MoS, the range of WBAM in the three planes, and duration of single limb support, as a% of the gait cycle43.

Kinematics data processing was performed with Plug-In-Gait within Vicon Nexus (Oxford metrics group, UK). All other computations were performed with custom Matlab (The Mathworks, USA) scripts. We checked our implementation of the MoS and the WBAM by comparing with results from similar studies (please find these comparisons in the supplementary material).

The distribution of the indices values was checked visually with boxplots. Outliers were identified and checked manually44. Linear mixed-effect models were fitted for each of the presumed index of stability independently. The models considered the following fixed effects: Subject group (TD or CP), Condition (flat or UG), the interaction between Subject group and Conditions, and Side (affected, aff, or sound). The models considered the following fixed effects: Subject group (TD or CP), Condition (flat or UG), the interaction between Subject group and Conditions, and Side (affected, aff, or sound). Contrary to children with unilateral CP, there is no affected and sound sides in TD children. For the TD group, the aff and sound sides were randomly associated with data from the left or the right side. In addition, we defined Side as nested within Subject group. We expected an influence of dimensionless walking speed on the indices and included it in the model as a continuous covariate. Subject ID was the only random effect.

The following is a mathematical representation of each model for the conditional expectation of y (each index of stability) given the predictors and conditional on individual characteristics not observed:

With \({\alpha }_{i}\) representing the unobserved characteristics of individual i and \({\epsilon }_{ij}\) the error term for each individual i and condition j. The models were fitted with the package lme4 in R with default options and the following formula45,46.

Statistical significance was set at \(\text{p}\le 0.05\) and p values were calculated with the package lmerTest47.

Results

Age between the two groups was not statistically significant. There was good agreement between the raw and fitted values from the statistical models. Boxplots depicting the raw and model fitted distribution of the indices, as well as evaluation plots of the models fitting (residuals) are available as supplementary materials. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the mean (SD) values for each condition and the estimated model coefficients.

Except for the lateral MoS, all indices were significantly associated with a difference between the flat and UG conditions. For all indices except duration of single limb support (%), the coefficient was positive, indicating the values increased for the UG condition compared to flat. Conversely, all indices except for the range of WBAM in the sagittal plane were not significantly associated with Subject group. For the range of WBAM in the sagittal plane, the coefficient was positive, indicating the range increased for the CP group compared to TD.

There was a significant interaction between subject groups and sides in the CP group for the anterior MoS, duration of single limb support (%), and the GaitSD. For the affected side in the CP group, anterior MoS, duration of single limb support (%), and GaitSD were smaller. Figure 2 depicts these relationships and post-hoc tests for the two groups.

There was a significant interaction and positive coefficients between conditions and subject groups for the range of WBAM in the coronal and transverse planes and for GaitSD, indicating that values increased further in the CP compared to the TD group for the UG condition.

Dimensionless walking speed had a large effect on the anterior MoS (negative coefficient), the range of WBAM in the sagittal and transverse planes (positive coefficients), and duration of single limb support (%, positive coefficient).

Discussion

We primarily aimed to clarify the interpretation of common indices of overground gait stability using an approach based on two postulates: (1) children with CP are less stable than TD children and (2) all children are less stable on UG compared to flat surface when walking barefoot. A postulate-based approach was required to avoid the pitfall of considering a priori that a large MoS, i.e. a stable gait pattern, is adopted by persons that are stable during walking.

We found coherent results across all indices, with the same direction for the two postulates. Decreased stability from the TD to CP groups and from the flat to UG conditions was associated with increased anterior and lateral MoS, increased range of the WBAM in all planes, decreased duration of single limb support phase, and increased variability of the lower limb kinematics and spatio-temporal parameters (Table 1).

Our findings confirm previous studies about the change of MoS in persons with impaired stability3,7,8. A stable gait pattern from the point of view of the MoS seems to be associated with less stable persons, rather than the opposite. The more dynamically stable gait pattern may be related to stiffer coordination between adjacent body segments. For example, increased coordination stiffness between the head and the trunk was noted in previous studies investigating the effect of increasing level of motor task difficulties on coordination in TD children and children with internal rotation gait48,49.

However, interpretation remains difficult because side was a significant effect for the anterior MoS within the unilateral CP group, and the direction was counterintuitive. There was decreased anterior MoS for the affected compared to the sound side in the context of an increased MoS for the two sides (Table 1). Therefore, what is true at the person level seems to be contradicted at the side level. Indeed, it would be counter-intuitive to consider the affected side (small MoS) is more stable than the sound side (larger MoS) in children with unilateral CP (Figs. 1 and 2).

Here, we should consider a detail about the calculation of the MoS and the contribution of the two sides to propulsion in children with unilateral CP. The MoS presented in this study was calculated at foot strike, as is customary3. In children with unilateral CP, the affected side tends to contribute less to propulsion and makes smaller step length50. Therefore, the basis of support in the anterior direction is reduced and the position of xCoM is further forward because propulsion (from the contralateral side) is increased at the time of foot strike of the affected side. Such a combination may be labelled as ‘fall forward’ gait (Fig. 1, middle picture).

We conclude that although MoS is an instantaneous measure of mechanical stability51, it is difficult to interpret and may not be considered a clinically useful indicator of gait stability, especially for the anterior MoS and in case of asymmetry between the sides. On the one hand, TD children presented with smaller MoS compared to CP overall, and smaller MoS walking on flat compared to UG indicating that stable persons tend to adopt a walking pattern with small (including negative) MoS. On the other hand, in children with unilateral CP, the affected side has a small MoS which does not indicate improved stability but rather a walking strategy that involves falling forward on this side.

One limitation of our study is that we used markers located on the foot to define the boundary of support for the MoS. This is a frequent choice that maximises the size of the potential boundary of support in many situations3. However, using a fixed marker may bias the results when foot contact is markedly different between individuals, e.g. out-toeing heel contact vs in-toeing forefoot contact. Using the centre of pressure (CoP) at initial contact may provide fairer comparison in these cases. In this study, we could not determine the position of the CoP during the UG condition. In supplementary materials, we show that the results do not change if we use a different marker (the heel instead of toe marker).

Contrary to the anterior MoS, the interpretation of the duration of single limb support is consistent overall and at the side level within the CP group. Duration of single limb support was also sensitive with significant decrease associated with the UG condition and for the affected side in unilateral CP. Duration of single limb support may be measured with a range of technology, including low-cost inertial measurement units, and as such appears as a promising index of stability for overground walking. However, walking speed was a significant and strong effect and would need to be considered when comparing results between groups with different walking speed. Similarly, walking speed had a significant and strong effect on the anterior MoS and the range of the WBAM in the sagittal and transverse planes.

The WBAM in the sagittal plane was sensitive to differences between the ground conditions and the subject groups. The WBAM in the coronal and transverse planes was less sensitive to the group condition, but the indices detected a significant interaction between subject group and condition. The WBAM was available for the two sides because the indices were available for the left and right strides. However, the WBAM include the contribution of all body segments, from both sides, for either stride side. As a result, the WBAM was not sensitive to the side. Of note, walking speed had an effect not only on the WBAM in the sagittal plane but also in the transverse plane.

Interestingly, indices based on variability of the kinematics pattern (GaitSD) or spatio-temporal parameters (step length and stride width) did not detect significant differences between groups, only between walking conditions, and the estimated coefficient were twice as large between conditions than between groups.

Overall, considering the estimated coefficients from all indices, we note that the UG condition induced a challenge to maintaining balance during gait larger than mild CP compared to TD. We believe these results confirm the benefits of exposure to more challenging environment, such as UG, to investigate stability in clinical population52.

Conclusion

The results of this study clarified how to interpret the direction of the MoS, at least in children with CP and TD. In these populations, larger MoS meant less stability and not the contrary. However, the interpretation remains difficult, in particular in the sagittal plane, because small (including negative) MoS may be a sign of good stability or a fall forward gait strategy.

The range of the WBAM and the duration of single limb support (expressed as % of the gait cycle) may be considered better indices of stability during walking since the interpretation of the indices was consistent and both indices appeared sensitive.

Data availability

All data analysed in this study are included in the Supplementary Information files, as well as the code to reproduce the analysis, produce the results, and the additional graphs available in the supplementary html page.

References

Baker, R. Gait analysis methods in rehabilitation. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 3, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-3-4 (2006).

Bruijn, S. M., Meijer, O. G., Beek, P. J. & van Dieën, J. H. Assessing the stability of human locomotion: A review of current measures. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20120999. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0999 (2013).

Watson, F. et al. Use of the margin of stability to quantify stability in pathologic gait - a qualitative systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 597. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04466-4 (2021).

Hof, A. L., Gazendam, M. G. J. & Sinke, W. E. The condition for dynamic stability. J. Biomech. 38, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.025 (2005).

Hof, A. L. The equations of motion for a standing human reveal three mechanisms for balance. J. Biomech. 40, 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.12.016 (2007).

Kazanski, M. E., Cusumano, J. P. & Dingwell, J. B. Rethinking margin of stability: Incorporating step-to-step regulation to resolve the paradox. J. Biomech. 144, 111334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2022.111334 (2022).

Rethwilm, R. et al. Dynamic stability in cerebral palsy during walking and running: Predictors and regulation strategies. Gait Posture 84, 329–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.12.031 (2021).

Vistamehr, A., Kautz, S. A., Bowden, M. G. & Neptune, R. R. Correlations between measures of dynamic balance in individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis. J. Biomech. 49, 396–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.12.047 (2016).

Grigoriu, A. I., Brochard, S., Sangeux, M., Padure, L. & Lempereur, M. Reliability and sources of variability of 3D kinematics and electromyography measurements to assess newly-acquired gait in toddlers with typical development and unilateral cerebral palsy. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 58, 102544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2021.102544 (2021).

Grigoriu, A. I., Lempereur, M., Bouvier, S., Padure, L. & Brochard, S. Characteristics of newly acquired gait in toddlers with unilateral cerebral palsy: Implications for early rehabilitation. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 64, 101333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2019.10.005 (2021).

Hallemans, A. et al. Developmental changes in spatial margin of stability in typically developing children relate to the mechanics of gait. Gait Posture 63, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.04.019 (2018).

Wist, S. et al. Gait stability in ambulant children with cerebral palsy during dual tasks. PLoS One 17, e0270145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270145 (2022).

Herr, H. & Popovic, M. Angular momentum in human walking. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.008573 (2008).

Negishi, T. & Ogihara, N. Regulation of whole-body angular momentum during human walking. Sci. Rep. 13, 8000. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34910-5 (2023).

Silverman, A. K. & Neptune, R. R. Differences in whole-body angular momentum between below-knee amputees and non-amputees across walking speeds. J. Biomech. 44, 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.027 (2011).

Silverman, A. K., Wilken, J. M., Sinitski, E. H. & Neptune, R. R. Whole-body angular momentum in incline and decline walking. J. Biomech. 45, 965–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.012 (2012).

Nott, C. R., Neptune, R. R. & Kautz, S. A. Relationships between frontal-plane angular momentum and clinical balance measures during post-stroke hemiparetic walking. Gait Posture 39, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.06.008 (2014).

Brach, J. S., Berlin, J. E., VanSwearingen, J. M., Newman, A. B. & Studenski, S. A. Too much or too little step width variability is associated with a fall history in older persons who walk at or near normal gait speed. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-2-21 (2005).

Hamacher, D., Singh, N. B., Van Dieën, J. H., Heller, M. O. & Taylor, W. R. Kinematic measures for assessing gait stability in elderly individuals: A systematic review. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 1682–1698. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2011.0416 (2011).

Skiadopoulos, A., Moore, E. E., Sayles, H. R., Schmid, K. K. & Stergiou, N. Step width variability as a discriminator of age-related gait changes. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 17, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-00671-9 (2020).

Sangeux, M., Passmore, E., Graham, H. K. K. & Tirosh, O. The gait standard deviation, a single measure of kinematic variability. Gait Posture 46, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.015 (2016).

McGinley, J., Wolfe, R., Morris, M., Pandy, M. G. & Baker, R. Variability of walking in able-bodied adults across different time intervals. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Sci. 17, 6–10 (2014).

Gage, J. R. Gait analysis in cerebral palsy (Mac Keith Press, 1991).

J. Perry, Normal and pathological gait, University of California, 1980.

Schwartz, M. H., Rozumalski, A. & Trost, J. P. The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J. Biomech. 41, 1639–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.03.015 (2008).

Ertürk, G., Akalan, N. E., Evrendilek, H., Karaca, G. & Bilgili, F. The relationship of one leg standing duration to GMFM scores and to stance phase of walking in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Physiother. Theory Pract. 38, 2170–2174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2021.1920078 (2022).

Romkes, J., Freslier, M., Rutz, E. & Bracht-Schweizer, K. Walking on uneven ground: How do patients with unilateral cerebral palsy adapt?. Clin. Biomech. 74, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.02.001 (2020).

Boyer, E. R. & Patterson, A. Gait pathology subtypes are not associated with self-reported fall frequency in children with cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 63, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.05.004 (2018).

Donker, S. F., Ledebt, A., Roerdink, M., Savelsbergh, G. J. P. & Beek, P. J. Children with cerebral palsy exhibit greater and more regular postural sway than typically developing children. Exp. Brain Res. 184, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1105-y (2008).

Reynolds, R. F. The ability to voluntarily control sway reflects the difficulty of the standing task. Gait Posture 31, 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.09.001 (2010).

Ryan, J. M. et al. Incidence of falls among adults with cerebral palsy: A cohort study using primary care data. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 62, 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14444 (2020).

Opheim, A., McGinley, J. L., Olsson, E., Stanghelle, J. K. & Jahnsen, R. Walking deterioration and gait analysis in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 37, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.06.032 (2013).

Zurales, K. et al. Gait efficiency on an uneven surface is associated with falls and injury in older subjects with a spectrum of lower limb neuromuscular function: A prospective study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000324 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: A neglected public health problem. Am. J. Public Health 96, 1192–1200. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.083055 (2006).

Dixon, P. C. et al. Gait adaptations of older adults on an uneven brick surface can be predicted by age-related physiological changes in strength. Gait Posture 61, 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.01.027 (2018).

Talbot, L. A., Musiol, R. J., Witham, E. K. & Metter, E. J. Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: Perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Public Health 5, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-86 (2005).

Baker, R., Leboeuf, F., Reay, J., Sangeux, M.: The conventional gait model - success and limitations. In: Müller, B., Wolf, S.I., Brueggemann, G.-P., Deng, Z., McIntosh, A., Miller, F., Selbie, W.S., Müller, B., Wolf, S.I., Brueggemann, G.-P., Deng, Z., McIntosh, A., Miller, F., Selbie, W.S. (Eds.), Handbook of human motion. Cham, pp. 1–19 (2017).

Dumas, R. & Wojtusch, J. Estimation of the body segment inertial parameters for the rigid body biomechanical models used in motion analysis. In Handbook of human motion (eds Müller, B. et al.) 1–31 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30808-1_147-1.

Robert, T., Bennett, B. C., Russell, S. D., Zirker, C. A. & Abel, M. F. Angular momentum synergies during walking. Exp. Brain Res. 197, 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-009-1904-4 (2009).

Hof, A. L. A. L. Scaling gait data to body size. Gait Posture 4, 222–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/0966-6362(95)01057-2 (1996).

Caderby, T. et al. Influence of aging on the control of the whole-body angular momentum during volitional stepping: An UCM-based analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 178, 112217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2023.112217 (2023).

Baker, R. Measuring walking: A handbook of clinical gait analysis (Mac Keith Press, 2013).

Sangeux, M. & Polak, J. A simple method to choose the most representative stride and detect outliers. Gait Posture 41, 726–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.12.004 (2015).

Kassambara, A.: rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests, 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix.

R Core Team, R Development Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, (2014). http://www.r-project.org/.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

Assaiante, C., Mallau, S., Viel, S., Jover, M. & Schmitz, C. Development of postural control in healthy children: A functional approach. Neural Plast. 12, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1155/NP.2005.109 (2005).

Mallau, S. et al. Locomotor skills and balance strategies in children with internal rotations of the lower limbs. J. Orthop. Res. 26, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20476 (2008).

Bracht-Schweizer, K., Romkes, J., Widmer, B., Viehweger, E. & Sangeux, M. Effects of walking with hinged ankle-foot-orthosis on propulsion and body weight support in unilateral cerebral palsy. Gait Posturehttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.07.040 (2023).

Curtze, C., Buurke, T., McCrum, C.: Notes on the margin of stability (2023). https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/nym5w.

Dussault-Picard, C., Mohammadyari, S. G., Arvisais, D., Robert, M. T. & Dixon, P. C. Gait adaptations of individuals with cerebral palsy on irregular surfaces: A scoping review. Gait Posture 96, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.05.011 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded through the University of Basel Research Fund. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Andrea Wiencierz, senior statistician, Department of Clinical Research at the University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. conceived the presented ideas, processed the data, analysed the results, and wrote the first draft. E.V. encouraged M.S. to investigate the topic, reviewed the ideas, and reviewed the final manuscript. J.R. helped design the experiments, participated in the data collection and processing, and reviewed the final manuscript. K.B.W. acquired funding, designed the experiments, collected the data, participated in the data processing, and reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sangeux, M., Viehweger, E., Romkes, J. et al. On the clinical interpretation of overground gait stability indices in children with cerebral palsy. Sci Rep 14, 26363 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76598-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76598-1

This article is cited by

-

Structural brain correlates of balance control in children with cerebral palsy: baseline correlations and effects of training

Brain Structure and Function (2025)

-

Probing gait adaptations: The impact of aging on dynamic stability and reflex control mechanisms under varied weight-bearing conditions

European Journal of Applied Physiology (2025)