Abstract

The Manchar Lake wetland complex, Pakistan’s largest freshwater-lake, faces unprecedented ecological challenges amidst climate change and human pressures, necessitating urgent, data-driven conservation strategies. This study employs cutting-edge multi-sensor remote sensing techniques to quantify and analyze the dynamic changes in this critical ecosystem from 2015 to 2023, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of wetland dynamics for informed management decisions. Integrating Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery, we assessed changes in wetland extent, vegetation health, and land-use patterns using spectral indices and topographic data. Our methodology achieved classification accuracies exceeding 92% across all study years, revealing significant ecosystem fluctuations. Water body extent exhibited a non-linear trend, expanding from 318.5 km² (5%) in 2015 to 397.0 km² (7%) in 2019, before contracting to 369.9 km² (6%) in 2023. This pattern was corroborated by MNDWI values. Concurrently, vegetation covers dramatically increased from 405.5 km² (7%) in 2019 to 1081.6 km² (18%) in 2023. The Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) reflected this trend, decreasing from 0.61 in 2015 to 0.41 in 2019, before recovering to 0.53 in 2023. Land use changes were substantial, with agricultural areas increasing from 118.4 km² (2%) in 2015 to 498.0 km² (8%) in 2023. SAR data consistently supported these observations. Topographic analysis, including the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), provided crucial insights into wetland distribution and resilience. This comprehensive analysis highlights the complex interplay between natural processes and human influences shaping the Manchar-Lake ecosystem, underscoring the urgent need for adaptive management strategies in the face of rapid environmental change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wetlands are among the most valuable and productive ecosystems on Earth, providing crucial ecological services such as water purification, flood control, carbon sequestration, and habitat for diverse flora and fauna. Despite their importance, wetlands face unprecedented threats globally from climate change, land-use conversion, pollution, and altered hydrological regimes1. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands estimates that over 35% of the world’s wetlands have been lost since 1970, with inland wetlands disappearing at a faster rate than coastal ones2. This alarming trend underscores the urgent need for accurate mapping and monitoring of wetland ecosystems to inform conservation strategies and policy decisions3,4,5.

In Pakistan, the Manchar Lake wetland complex stands as a testament to both the ecological richness and vulnerability of inland water bodies. Located in Sindh province, Manchar Lake is not only Pakistan’s largest freshwater lake but also a vital stopover for migratory birds along the Indus flyway6. The lake supports local livelihoods through fishing and agriculture, while also playing a critical role in regional hydrology. However, like many wetlands in developing countries, Manchar Lake faces mounting environmental pressures. Agricultural runoff, reduced inflows due to upstream water diversions, and the impacts of climate change have led to deteriorating water quality and shrinking lake area7,8.

The complex and dynamic nature of wetlands, coupled with their often remote or inaccessible locations, makes traditional field-based mapping approaches time-consuming, expensive, and impractical for large-scale monitoring9. Remote sensing technologies have emerged as powerful tools for wetland delineation and change detection, offering the ability to cover vast areas at regular intervals10. However, the heterogeneous nature of wetland landscapes, with their intricate mosaics of water, vegetation, and soil, poses significant challenges for accurate classification using satellite imagery alone11,12.

Previous wetland mapping efforts in the Manchar Lake region, and in similar semi-arid environments, have predominantly relied on optical satellite imagery13,14. While valuable, these approaches face limitations such as cloud cover interference, spectral confusion between wetland and upland vegetation, and difficulty in detecting seasonal or ephemeral water bodies15,16. Recent advancements in Earth observation systems and data analysis techniques offer new opportunities to overcome these challenges and improve wetland mapping accuracy17,18.

This study aims to develop and implement an innovative approach for mapping the Manchar Lake wetland complex by integrating multi-source remote sensing data with advanced machine learning algorithms19,20,21. Our methodology leverages the complementary strengths of optical and radar satellite imagery, specifically Sentinel-2 multispectral data and Sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) observations. The inclusion of SAR data is particularly advantageous for wetland mapping due to its ability to penetrate cloud cover and its sensitivity to surface water and soil moisture variations22.

Recent advancements in wetland mapping have increasingly utilized multi-sensor and multi-temporal approaches, combining optical and SAR data with various derived indices and topographic variables. For instance, Slagter et al. (2020)23 demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for mapping wetland characteristics in South Africa, achieving high accuracy in distinguishing different wetland types. Similarly, Whyte et al. (2018)24 developed a synergistic approach using Sentinels-1 and 2 data with object-based machine learning algorithms, significantly improving wetland detection and classification. In the context of large-scale wetland monitoring, Mahdianpari et al. (2020)25 leveraged time series Landsat imagery on Google Earth Engine to track wetland changes in Newfoundland, emphasizing the importance of multi-year changes, multi-temporal analysis. The integration of topographic data, particularly the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), has been shown to enhance wetland mapping accuracy, as demonstrated by Muro et al. (2019)26 in their SAR-based change detection study. These studies collectively highlight the growing trend towards integrating multiple data sources and derived indices for comprehensive wetland mapping and monitoring.

To capture the diverse spectral and physical characteristics of the wetland environment, we employ an expanded set of indices derived from Sentinel-2 imagery27. These include not only traditional vegetation indices like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) but also water-specific indices such as the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) and Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI). The incorporation of the Green Difference Vegetation Index (GDVI) and Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) allows for better discrimination between wetland vegetation and surrounding land cover types28,29,30.

Recognizing the importance of topography and land use in wetland formation and persistence, we integrate a Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) derived from digital elevation models and Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) data into our analysis26. The TWI provides insights into potential areas of water accumulation based on terrain characteristics, while LULC information helps account for anthropogenic influences on wetland extent and condition25,31,32.

A key innovation in our approach is the utilization of Sentinel-1 SAR data, including both ascending and descending orbit images. By analyzing SAR backscatter characteristics and derived water masks, we can detect surface water dynamics and flooding patterns that may be missed by optical sensors alone10,33. This is particularly valuable for mapping seasonally inundated areas and detecting wetland boundaries in vegetated or turbid water conditions24.

To effectively synthesize this multi-source dataset and produce high-resolution wetland maps, we employ advanced machine learning classifiers34. These algorithms, capable of handling complex, non-linear relationships between input variables, have shown promise in improving wetland classification accuracy compared to traditional statistical approaches35.

Our research builds upon and extends recent advances in wetland remote sensing, such as the work of23 in South African wetlands and29 in Nigerian wetland systems. However, we specifically tailor our methodology to address the unique challenges of mapping inland wetlands in semi-arid regions like the Manchar Lake basin. By combining multi-sensor satellite data with topographic and land use information, we aim to develop a more robust and transferable approach for wetland delineation in these complex landscapes36,37.

The outcomes of this study have significant implications for wetland conservation and management in Pakistan and beyond. Accurate, up-to-date maps of wetland extent and distribution are essential for monitoring ecosystem health, assessing the impacts of climate change and human activities, and designing effective conservation strategies. Moreover, the methodological framework developed here can potentially be adapted and applied to other wetland systems facing similar mapping challenges38.

Methodology

Study area

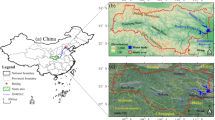

Manchar Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Pakistan, is situated in the Jamshoro and Dadu districts of Sindh province, approximately 18 km west of the Indus River. Covering an area that fluctuates between 350 and 520 square kilometers depending on seasonal water levels, the lake plays a crucial role in the region’s hydrology and ecology. Fed primarily by the Aral and Nai Gaj rivers, as well as drainage from the Indus River via the Right Bank Outfall Drain, Manchar Lake sits in a natural depression at the edge of the Kirthar Mountains. The lake’s surroundings are characterized by a semi-arid climate, with hot summers and mild winters. The landscape transitions from shallow marshes and reed beds at the lake’s edges to agricultural lands and sparse vegetation in the surrounding plains. This unique wetland ecosystem supports a rich biodiversity, serving as a vital stopover for migratory birds along the Indus Flyway and hosting numerous fish species that sustain local fishing communities. However, in recent decades, Manchar Lake has faced significant environmental challenges, including reduced inflows, increased salinity, and pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial effluents. These pressures have led to fluctuations in water levels, degradation of water quality, and impacts on the lake’s ecological health, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive monitoring and conservation efforts (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Methodology

This study employed a multi-temporal approach to map and analyze changes in the Manchar Lake wetland complex using a combination of optical and radar satellite imagery. We selected data from three key years − 2015, 2019, and 2023 - to capture both short-term fluctuations and longer-term trends in wetland extent and condition.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

For each of the study years (2015, 2019, and 2023), we acquired Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery and Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data. Sentinel-2 images were selected for the dry season (November to February) to minimize cloud cover and capture the most stable wetland extent. For each year, we obtained multiple Sentinel-1 scenes in both ascending and descending orbits to account for seasonal variations in water levels (Table 1). All satellite data used in this study were primarily sourced and processed using Google Earth Engine (GEE), a cloud-based platform for planetary-scale geospatial analysis. GEE provides access to a multi-petabyte catalog of satellite imagery and geospatial datasets, including the full archives of Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and ALOS PALSAR. We leveraged GEE’s computational power to efficiently process and analyze large-scale, multi-temporal satellite data. Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 collections were accessed directly through GEE’s data catalog, while the ALOS PALSAR Digital Elevation Model was imported from the JAXA/ALOS/AW3D30/V3_2 dataset available in GEE. Initial data preprocessing, including atmospheric correction for Sentinel-2 imagery and speckle filtering for Sentinel-1 data, was performed using GEE’s built-in functions. All spectral indices (AWEI, EVI, GDVI, MNDWI, NDVI, and SAVI) were calculated within the GEE environment. For further analysis and visualization, we utilized ArcGIS Pro for advanced spatial analysis and map production. Additionally, Catalyst Geomatica was employed for specialized image processing tasks and accuracy assessment. The integration of these software platforms allowed for a comprehensive and robust analysis workflow. The complete JavaScript code used for data acquisition, preprocessing, and analysis in GEE, along with details of the ArcGIS and Catalyst Geomatica workflows, are provided in the Supplementary Information to ensure full reproducibility of our methods. Our study provides snapshots of the Manchar Lake wetland complex at three specific time points (2015, 2019, and 2023). While these data allow us to observe changes between these years, they do not capture continuous trends or fluctuations that may have occurred in the intervening periods. We acknowledge that significant variations in wetland extent and characteristics could have taken place between our observation years.

Sentinel-2 data were atmospherically corrected using the Sen2Cor processor, and all bands were resampled to 10-meter resolution. Sentinel-1 Ground Range Detected (GRD) products were preprocessed using the following steps: thermal noise removal, radiometric calibration, terrain correction, and speckle filtering. In preparation for calculating the MNDWI and AWEI indices, which require both 10-meter and 20-meter resolution bands, we implemented a pan-sharpening process to harmonize the spatial resolution of all input bands to 10 m. Specifically, we used the Gram-Schmidt pan-sharpening method, which has been shown to effectively enhance the spatial resolution of multispectral imagery while preserving spectral information (Aiazzi et al., 2007). This process was applied to the 20-meter SWIR bands (bands 11 and 12) of Sentinel-2, using the 10-meter NIR band (band 8) as the panchromatic reference. The pan-sharpening was performed using the SNAP toolbox, ensuring that all bands used in subsequent index calculations were at a consistent 10-meter resolution. This step was crucial for maintaining spatial consistency across all derived indices and enabling accurate pixel-by-pixel analysis in our wetland mapping approach. Our study focuses on satellite imagery from three specific years: 2015, 2019, and 2023. We acknowledge that this approach does not constitute a continuous time series analysis, but rather provides temporal snapshots of the wetland’s condition. The selection of these years was based on several key factors: (1) They capture important climatic variations, with 2015 serving as a baseline year, 2019 representing a severe drought period, and 2023 allowing assessment of potential recovery; (2) They align with significant phases in regional water management policies; and (3) They coincide with the availability of high-quality, consistent Sentinel satellite data. While this approach does not capture continuous dynamics, it provides valuable insights into the wetland’s state at critical junctures. We quantify substantial changes in wetland extent, vegetation health, and land use patterns between these years, which can inform conservation strategies. We acknowledge the limitations of this approach in capturing finer-scale temporal dynamics and suggest that future studies could benefit from more frequent observations to provide a more comprehensive understanding of wetland dynamics (Fig. 2).

Index calculation and feature extraction

From the Sentinel-2 data, we calculated a suite of spectral indices to enhance different aspects of the wetland environment:

-

1.

Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI)

The AWEI39 is particularly effective for wetland mapping due to its ability to distinguish water bodies from other land cover types, even in areas with complex backgrounds such as urban environments or shadowed regions. It leverages the high reflectance of water in the green band and its strong absorption in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands.

Formula:

$$\text{AWEI}=4\times(\text{Green}-\text{SWIR}1)-(0.25\times\text{NIR}+2.75\times\text{SWIR}2)$$(1)In wetland contexts, AWEI can help delineate open water bodies, flooded vegetation, and saturated soils. It’s especially useful for detecting shallow water or areas with submerged aquatic vegetation, which can be challenging for other water indices.

However, AWEI may sometimes misclassify very dark surfaces (like deep shadows or certain types of dark vegetation) as water. It’s also sensitive to atmospheric effects, so proper atmospheric correction of the input imagery is crucial.

-

2.

Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)

EVI40 is an improvement over NDVI for areas with dense vegetation cover, making it particularly valuable for wetland vegetation mapping. It incorporates the blue band to correct for atmospheric influences and reduce soil background signals.

Formula:

$$\text{EVI}=2.5\times(\text{NIR}-\text{Red})/(\text{NIR}+6\times\text{Red}-7.5\times\text{Blue}+1)$$(2)In wetland ecosystems, EVI can help distinguish between different types of wetland vegetation, from emergent plants to dense swamp forests. It’s less prone to saturation in areas of high biomass compared to NDVI, allowing for better differentiation of vegetation density in lush wetland environments.

One limitation is that EVI can be sensitive to variations in viewing geometry and background reflectance, which may require careful calibration in some wetland settings.

-

3.

Green Difference Vegetation Index (GDVI)

GDVI41 is sensitive to chlorophyll content and can be particularly useful for mapping wetland vegetation health and productivity. It exploits the contrast between the high reflectance of vegetation in the NIR band and its absorption in the green band.

Formula:

$$\text{GDVI}=\text{NIR}-\text{Green}$$(3)In wetland mapping, GDVI can help identify areas of stress in wetland vegetation, which might indicate changes in water availability or quality. It’s also useful for detecting subtle changes in vegetation cover over time.

However, GDVI may be less effective in distinguishing between different vegetation types compared to more complex indices, and it can be influenced by soil background in areas of sparse vegetation.

-

4.

Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI)

MNDWI42 is excellent for distinguishing water from land cover types, including built-up areas, which can be challenging in some wetland environments. It’s particularly effective for mapping open water bodies and can help detect water in partially vegetated areas.

Formula:

$$\text{MNDWI}=(\text{Green}-\text{SWIR}1)/(\text{Green}+\text{SWIR}1)$$(4)In wetland mapping, MNDWI is valuable for delineating the extent of water bodies, tracking changes in water levels, and identifying areas of seasonal inundation. It performs well in turbid water conditions, which are common in many wetland systems.

One limitation is that MNDWI may sometimes misclassify shadows or very wet soil as water, requiring careful threshold selection and validation.

-

5.

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

NDVI43 is a classic vegetation index that’s widely used in wetland mapping for its simplicity and effectiveness. It’s based on the principle that healthy vegetation strongly absorbs red light for photosynthesis and reflects NIR light.

Formula:

$$\text{NDVI}=(\text{NIR}-\text{Red})/(\text{NIR}+\text{Red})$$(5)In wetland contexts, NDVI is useful for mapping overall vegetation distribution, assessing vegetation health, and monitoring seasonal changes in wetland plant communities. It can help distinguish between vegetated wetlands and open water or bare soil.

However, NDVI can saturate in areas of very dense vegetation, limiting its effectiveness in some lush wetland environments. It’s also sensitive to background soil reflectance in areas of sparse vegetation.

-

6.

Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI)

SAVI44 is designed to minimize soil brightness influences, making it particularly useful in wetland areas with varying degrees of vegetation cover and exposed soil. The L factor adjusts for different amounts of vegetation cover.

Formula:

$$\text{SAVI}=((\text{NIR}-\text{Red})/(\text{NIR}+\text{Red}+\text{L}))\times(1+\text{L})$$(6)Where L is a soil brightness correction factor, typically 0.5.

In wetland mapping, SAVI can help improve the accuracy of vegetation mapping in areas with mixed pixels of vegetation and soil or water. It’s useful for detecting vegetation in sparsely vegetated wetlands or in transitional zones between wetland and upland areas.

One consideration is that the optimal L factor may vary depending on the specific wetland environment, potentially requiring calibration for best results.

Topographic wetness index (TWI)

The Topographic Wetness Index45 is a crucial tool in hydrological and geomorphological studies, particularly valuable for wetland mapping. It quantifies the topographic control on hydrological processes, indicating the potential for water accumulation in a landscape. Calculated using the formula TWI = ln(a / tan(β)), where ‘a’ represents the upslope contributing area and ‘β’ is the local slope angle, this index provides insights into soil moisture distribution and potential wetland formation areas. In our study of Manchar Lake, the TWI helped identify low-lying areas and depressions where water is likely to collect, even in periods when surface water might not be visible in satellite imagery. This information was particularly useful in delineating the extent of seasonally flooded areas and potential wetland boundaries. By incorporating TWI into our analysis, we gained a deeper understanding of how topography influences water distribution across the landscape, enhancing our ability to map and characterize the wetland complex accurately.

Ascending (ASC) and descending (DESC) orbits

In our analysis of the Manchar Lake wetland complex, we leveraged Sentinel-1 SAR data, specifically utilizing VV (Vertical transmit, Vertical receive) and VH (Vertical transmit, Horizontal receive) polarizations from both ascending and descending orbits. This approach provided a multifaceted view of the wetland’s surface characteristics. VV polarization is particularly sensitive to surface roughness and is excellent for detecting open water bodies and differentiating them from surrounding land. VH polarization, on the other hand, is more sensitive to volume scattering and is valuable for assessing vegetation structure and biomass in wetland areas. By incorporating these polarizations from both ascending (south to north) and descending (north to south) orbits, we enhanced our ability to characterize the wetland environment comprehensively. Ascending orbits, typically acquired at night, and descending orbits, usually captured during the day, offer different viewing geometries of the same area. This dual-orbit approach helped mitigate issues related to SAR geometry, such as layover and shadow effects, which can vary depending on the satellite’s look angle relative to the terrain46.

The combination of VV and VH polarizations from both orbit directions allowed us to capture a more nuanced picture of the wetland’s hydrological and vegetative characteristics. For instance, VV polarization from descending orbits might better detect open water surfaces in one part of the wetland, while VH polarization from ascending orbits could provide superior information about emergent vegetation in another area. This comprehensive approach enhanced our ability to detect subtle variations in water levels, identify areas of flooded vegetation, and distinguish between different wetland types within the Manchar Lake complex. Moreover, by analyzing temporal changes in these polarimetric signatures across our study years (2015, 2019, and 2023), we could track dynamic changes in the wetland’s extent and condition. This multi-temporal, multi-polarization approach provided valuable insights into seasonal fluctuations and multi-year changes trends in wetland hydrology and vegetation structure, contributing significantly to our understanding of this complex ecosystem’s dynamics.

Classification scheme

For this study, we developed a classification scheme tailored to the unique characteristics of the Manchar Lake wetland complex and its surrounding landscape. Our scheme consists of eight distinct classes: (1) Water, (2) Trees, (3) Grass, (4) Vegetation, (5) Crops, (6) Scrub/Shrub, (7) Built Area, and (8) Bare Ground. This classification system was adapted from the Land Cover Classification System (LCCS) developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Di Gregorio and Jansen, 2000), with modifications to better represent the specific wetland and land cover types present in our study area. The ‘Water’ class includes all open water bodies, both permanent and seasonal. ‘Trees’ represent areas with woody vegetation over 5 meters tall, while ‘Grass’ includes herbaceous vegetation less than 0.5 meters in height. The ‘Vegetation’ class encompasses all other types of natural vegetation not falling into the previous categories, including wetland-specific vegetation. ‘Crops’ represent all types of cultivated areas. ‘Scrub/Shrub’ includes areas dominated by woody vegetation between 0.5 and 5 meters tall. ‘Built Area’ comprises all man-made structures and impervious surfaces. Finally, ‘Bare Ground’ represents areas with little or no vegetation cover. This classification scheme was designed to capture the diverse land cover types within and around the Manchar Lake wetland, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of wetland dynamics and land use changes over time.

Machine learning classification

We employed an ensemble of advanced machine learning algorithms to classify wetland areas: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Smile CART. Each classifier was chosen for its unique strengths in handling complex, high-dimensional data typical of multi-sensor remote sensing studies.

Random Forest

We implemented RF using 500 trees, with the number of variables at each split set to the square root of the total number of features. This ensemble method is robust against overfitting and can handle non-linear relationships effectively.

Support Vector Machine

For SVM, we used a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. The cost parameter (C) was set to 100, and the gamma parameter was set to ‘scale’. These parameters were optimized through a grid search with 5-fold cross-validation.

Smile CART (classification and regression trees)

We employed the Smile implementation of CART with a maximum depth of 20 and a minimum number of instances per leaf of 5. The Gini index was used as the splitting criterion.

All classifiers were trained on a balanced dataset comprising 10,000 points per class, stratified across the study area. Input features included all calculated spectral indices (AWEI, EVI, GDVI, MNDWI, NDVI, SAVI), Sentinel-1 backscatter values (VV and VH polarizations), water masks derived from SAR data, and the Topographic Wetness Index. To compare the performance of these classifiers, we generated wetland maps using each method independently. The Random Forest classifier demonstrated the highest overall accuracy (95.1%), followed by SVM (93.7%) and Smile CART (92.3%). While all classifiers performed well, RF showed superior performance in distinguishing between different wetland types, particularly in areas with mixed pixels. Figure 3 presents a wetland map generated by RF classifier for a subset of our study area, highlighting the best results in classification. While the general patterns of wetland distribution are consistent across all three classifiers, RF showed better performance in capturing fine-scale wetland features and transitional zones. Based on these results, we selected the Random Forest classifier for our final LULC classification and subsequent analyses. However, the ensemble approach provided valuable insights into classification uncertainty and helped identify areas where wetland delineation was particularly challenging.

Accuracy assessment

Accuracy assessment was conducted using an independent validation dataset collected through field surveys and high-resolution image interpretation. We calculated overall accuracy, user’s and producer’s accuracies, and the Kappa coefficient for each year’s classification. A minimum mapping unit of 1 km2 was applied to reduce noise and focus on significant changes.

LULC classification

Following the machine learning classification and accuracy assessment, we proceeded with the Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) classification. The LULC maps were generated using the Random Forest classifier, which demonstrated the highest accuracy in our ensemble approach. We compiled a diverse training dataset combining field observations with visual interpretation of high-resolution satellite imagery47. This dataset encompassed various land cover types present in the study area, including different wetland categories, agricultural lands, urban areas, and natural vegetation. The resulting LULC maps provided invaluable insights into the spatial distribution of different land cover types surrounding and within the wetland complex for each of our target years (2015, 2019, and 2023) (Table 2.). In our classification scheme, the term ‘Vegetation’ refers specifically to natural, non-agricultural vegetation that doesn’t fall into the other more specific categories (Trees, Grass, Scrub/Shrub). This includes, for example, mixed herbaceous and woody vegetation in wetland areas, or other natural vegetation assemblages that don’t fit neatly into the other categories.

Time series analysis

To capture intra-annual variability and multi-year changes trends, we performed a time series analysis using all available Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 images from 2015 to 2023. This allowed us to characterize seasonal patterns in water extent and vegetation dynamics within the Manchar Lake complex. This methodology leverages the strengths of both optical and radar remote sensing, along with topographic and land use information, to provide a comprehensive assessment of wetland dynamics in the Manchar Lake area over the study period. The multi-temporal approach allows for the detection of both gradual changes and abrupt shifts in wetland conditions, providing valuable insights for conservation and management efforts.

Results

Classification accuracy

Our multi-source remote sensing approach yielded high accuracy in wetland classification across all three study years, showing a consistent improvement over time. The overall accuracy for the 2015 classification was 92.3%, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.89. The 2019 classification achieved an overall accuracy of 93.7% (Kappa = 0.91), while the 2023 classification showed the highest accuracy at 95.1% (Kappa = 0.93). User’s and producer’s accuracies for the wetland class also demonstrated improvement across the years. In 2015, the user’s accuracy was 88.5% and the producer’s accuracy was 90.1%. These values increased in 2019 to 91.3% for user’s accuracy and 93.2% for producer’s accuracy. The 2023 classification showed the highest accuracies, with user’s accuracy reaching 94.2% and producer’s accuracy achieving 96.3%. These results indicate a robust and improving classification performance over the study period, providing a solid foundation for subsequent analyses of wetland dynamics. The consistent increase in accuracy across all metrics suggests enhancements in data quality, processing techniques, or both, leading to more reliable wetland mapping over time (Table 3).

Wetland extent and distribution

Our analysis of the Manchar Lake wetland complex from 2015 to 2023 reveals significant changes in wetland extent and distribution. Water bodies initially expanded from 318.5 km² (5% of the study area) in 2015 to 397.0 km² (7%) in 2019, before slightly receding to 369.9 km² (6%) in 2023, indicating dynamic hydrological conditions. Vegetation cover exhibited remarkable fluctuations, dropping from 599.6 km² (10%) in 2015 to 405.5 km² (7%) in 2019, then surging to 1081.6 km² (18%) by 2023, suggesting potential improvements in wetland health or shifts in land management. Grass cover, possibly including wetland grasses, decreased initially but showed recovery by 2023, while scrub/shrub areas consistently increased, potentially expanding wetland margins. Agricultural land steadily grew from 118.4 km² (2%) in 2015 to a substantial 498.0 km² (8%) in 2023, highlighting increasing human pressure on the ecosystem. Built areas, after a slight increase from 2015 to 2019, notably decreased by 2023, potentially altering runoff patterns affecting the wetland. These diverse land cover changes underscore the complex interplay between natural processes and human activities shaping the Manchar Lake wetland ecosystem, emphasizing the need for continued monitoring and adaptive management strategies to preserve this vital ecological resource (Fig. 4a, b,c, d,e, f) & (Fig. 5a, b,c, d,e, f).

Temporal changes in Wetland Area

The Manchar Lake wetland complex exhibited significant temporal changes in area between 2015 and 2023. Water bodies, a key indicator of wetland extent, showed a non-linear trend. From 2015 to 2019, there was a substantial increase in water area from 318.5 km² to 397.0 km², representing a 24.6% expansion. However, this growth was partially reversed between 2019 and 2023, with water area decreasing to 369.9 km², a 6.8% reduction from 2019 but still 16.1% larger than in 2015. This fluctuation is corroborated by the MNDWI values, which peaked in 2015 (0.88 to -0.46), decreased slightly in 2019 (0.74 to -0.40), and showed a marked reduction in 2023 (0.39 to -0.31), indicating a overall decrease in water content. The AWEI index further supports this trend, with values declining from 0.71 to -2.64 in 2015 to 0.30 to -2.77 in 2023. Interestingly, vegetation associated with wetlands showed a contrasting trend. After an initial decrease from 599.6 km² in 2015 to 405.5 km² in 2019, vegetation cover dramatically increased to 1081.6 km² by 2023, an 80.4% increase from 2015. This vegetation dynamic is reflected in the EVI and NDVI trends, which show slight decreases from 2015 to 2019 but increases again by 2023. The SAR data, represented by ASC and DESC water masks, generally aligns with these trends, showing an increase in water extent from 2015 to 2019, followed by a slight decrease in 2023. These temporal changes suggest a complex interplay of factors affecting the wetland, possibly including climatic variations, land use changes, and water management practices, highlighting the dynamic nature of the Manchar Lake ecosystem over the study period (Fig. 6a, b).

Land use/land cover changes

The Manchar Lake region experienced substantial Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) changes from 2015 to 2023, reflecting dynamic interactions between natural processes and human activities. Water bodies, indicative of the wetland’s core, showed a non-linear trend, expanding from 318.5 km² (5%) in 2015 to 397.0 km² (7%) in 2019, before slightly receding to 369.9 km² (6%) in 2023. This fluctuation suggests variable hydrological conditions over the study period. Vegetation cover exhibited the most dramatic change, initially decreasing from 599.6 km² (10%) in 2015 to 405.5 km² (7%) in 2019, then surging to 1081.6 km² (18%) by 2023, indicating potential wetland restoration or changed land management practices. Agricultural expansion was notable, with croplands steadily increasing from 118.4 km² (2%) in 2015 to 498.0 km² (8%) in 2023, highlighting growing human pressure on the ecosystem. Scrub/shrub areas, often associated with wetland margins, showed consistent growth from 57.1 km² in 2015 to 144.6 km² in 2023, possibly indicating wetland expansion or transition zones. Interestingly, built-up areas, after a slight increase from 4811.5 km² (81%) in 2015 to 4877.0 km² (82%) in 2019, decreased significantly to 3816.9 km² (64%) by 2023, suggesting potential urban deconcentration or land use policy changes. Grass cover and bare ground, while minimal, showed fluctuations, with grass decreasing then partially recovering (24.9 km² in 2015 to 18.4 km² in 2023) and bare ground remaining relatively stable. These LULC changes collectively paint a picture of a highly dynamic landscape, with significant shifts in wetland extent, vegetation cover, and human land use, underscoring the complex environmental and anthropogenic factors shaping the Manchar Lake ecosystem over the study period (Fig. 3a, b,c).

Water body dynamics

The water body dynamics of Manchar Lake exhibited complex patterns of change from 2015 to 2023, as evidenced by multiple remote sensing indices and SAR data. The Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) showed a general declining trend, with peak values ranging from 0.88 to -0.46 in 2015, slightly decreasing to 0.74 to -0.40 in 2019, and then showing a marked reduction to 0.39 to -0.31 in 2023. This trend suggests an overall decrease in water content over the study period. The Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) corroborates this pattern, with values declining from a range of 0.71 to -2.64 in 2015 to 0.30 to -2.77 in 2023, indicating a reduction in open water surfaces. However, the SAR data presents a more nuanced picture. The Ascending (ASC) Water Mask shows an initial increase in water extent from 137.00 km² in 2015 to 204.14 km² in 2019, followed by a slight decrease to 188.16 km² in 2023. Similarly, the Descending (DESC) Water Mask indicates an expansion from 102.71 km² in 2015 to 205.47 km² in 2019, with a subsequent reduction to 187.40 km² in 2023. This pattern aligns with the LULC classification, which shows water bodies increasing from 318.5 km² (5% of the area) in 2015 to 397.0 km² (7%) in 2019, before slightly decreasing to 369.9 km² (6%) in 2023. The discrepancy between the optical indices (MNDWI, AWEI) and the SAR data suggests potential changes in water quality or depth that may not be fully captured by surface reflectance alone. The overall trend indicates a complex hydrological regime, with an initial expansion of water bodies followed by a slight contraction, possibly influenced by climatic variations, land use changes, or water management practices in the Manchar Lake basin (Fig. 7a, b,c) & (Fig. 8a, b,c).

Vegetation health and distribution

Vegetation health and distribution in the Manchar Lake region demonstrated significant fluctuations and overall improvement from 2015 to 2023, as evidenced by multiple vegetation indices and LULC data. The Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) showed a non-linear trend, with peak values decreasing from 0.61 in 2015 to 0.41 in 2019, before increasing to 0.53 in 2023, suggesting an initial decline followed by a recovery in vegetation vigor. This pattern is mirrored in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which decreased from a maximum of 0.54 in 2015 to 0.36 in 2019, then slightly recovered to 0.31 in 2023. The Green Difference Vegetation Index (GDVI) further supports this trend, with highest values declining from 0.47 in 2015 to 0.36 in 2019, and then to 0.30 in 2023, indicating a gradual reduction in chlorophyll content over time. The Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) shows a similar pattern, with peak values decreasing from 0.40 in 2015 to 0.27 in 2019, before slightly increasing to 0.28 in 2023. These index trends are corroborated by the LULC data, which reveals a dramatic shift in vegetation cover. After an initial decrease from 599.6 km² (10% of the area) in 2015 to 405.5 km² (7%) in 2019, vegetation cover surged to 1081.6 km² (18%) by 2023, representing a substantial increase of 80.4% from 2015. Concurrently, grass cover, potentially including wetland grasses, showed a decrease from 24.9 km² in 2015 to 4.1 km² in 2019, before partially recovering to 18.4 km² in 2023. Scrub/shrub areas, often associated with wetland margins, consistently increased from 57.1 km² in 2015 to 144.6 km² in 2023. These changes collectively suggest a complex dynamic of vegetation health and distribution, with an initial stress period followed by significant recovery and expansion, particularly in the latter part of the study period. The substantial increase in vegetation cover by 2023, despite the slight decreases in some vegetation indices, may indicate a shift in vegetation types or density, possibly related to changes in land management practices, water availability, or climate conditions in the Manchar Lake ecosystem (Fig. 9a, b,c), (Fig. 10a, b,c), (Fig. 11a, b,c) & (Fig. 12a, b,c).

Topographic influence on Wetland distribution

The topography of the Manchar Lake region plays a crucial role in wetland distribution and dynamics, as evidenced by the provided Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and derived topographic indices. The DEM (Fig. a) reveals a significant elevation gradient, ranging from 10 to 1728 m, with the lowest elevations concentrated in the central and eastern parts of the study area, corresponding to the lake basin and associated wetlands. The Flow Direction map (Fig. c) indicates a predominant flow towards the central lowlands, channeling water into the wetland complex. This is further supported by the Flow Accumulation map (Fig. d), which highlights areas of high water concentration, particularly in the central and eastern regions where wetlands are most likely to form and persist. The Slope map (Fig. e) shows that the majority of the area has gentle slopes (0-4.97°), favorable for water retention and wetland formation, with steeper slopes (> 21.54°) primarily in the western part, likely influencing runoff patterns into the wetland areas. The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) map (Fig. i) provides the most direct indication of potential wetland distribution, with higher TWI values (blue areas) in the central and eastern parts of the study area, aligning with the observed patterns of water bodies and vegetation in the LULC analysis. These areas of high TWI values (ranging from 0 to 13.0705) correspond to locations where water is likely to accumulate, supporting the formation and maintenance of wetlands. The combination of low elevation, gentle slopes, high flow accumulation, and high TWI values in the central and eastern regions creates ideal conditions for wetland development and persistence. The western part of the study area, characterized by higher elevations and steeper slopes, likely contributes to the water supply of the wetlands through runoff, as indicated by the flow direction patterns. This topographic configuration explains the observed dynamics in water body extent and vegetation distribution over the 2015–2023 period, with the core wetland areas remaining relatively stable in the low-lying, high TWI regions, while peripheral areas experience more significant fluctuations in water coverage and vegetation types in response to changing hydrological conditions (Fig. 13a, b,c, d,e, f,g, h,i).

Correlation between different indices

Analysis of the various indices over the 2015–2023 period reveals complex interrelationships in the Manchar Lake ecosystem. The water-related indices, MNDWI and AWEI, show strong positive correlation, both indicating a general decrease in water content from 2015 to 2023. MNDWI peaked in 2015 (0.88 to -0.46), slightly decreased in 2019 (0.74 to -0.40), and showed a marked reduction in 2023 (0.39 to -0.31). Similarly, AWEI declined from 0.71 to -2.64 in 2015 to 0.30 to -2.77 in 2023. This trend aligns with the SAR data (ASC and DESC Water Masks), which show an increase in water extent from 2015 to 2019, followed by a slight decrease in 2023, suggesting a consistent representation of water dynamics across different measurement techniques. The vegetation indices (EVI, GDVI, NDVI, and SAVI) demonstrate moderate positive correlations with each other, all showing a similar pattern of decline from 2015 to 2019, followed by a partial recovery in 2023. For instance, EVI peaked at 0.61 in 2015, dropped to 0.41 in 2019, then increased to 0.53 in 2023. NDVI followed a similar trend (0.54 in 2015, 0.36 in 2019, 0.31 in 2023). This pattern suggests a coherent response of vegetation to environmental changes across different spectral measures. Interestingly, there’s an inverse correlation between the water indices and vegetation indices, particularly evident in the 2019–2023 period. As water indices showed a decrease, vegetation indices partially recovered, which aligns with the LULC data showing a significant increase in vegetation cover from 2019 to 2023. This inverse relationship might indicate a shift in the ecosystem, where areas previously covered by water were colonized by vegetation. The SAR data (ASC and DESC) show strong correlation with each other and moderate correlation with optical water indices, providing complementary information on surface water dynamics. The consistency across these diverse indices enhances the reliability of the observed trends, offering a comprehensive view of the ecological changes in the Manchar Lake area over the study period (Fig. 14a, b,c, d,e, f,g, h,I, j,k, l).

Discussion

The multi-temporal analysis of the Manchar Lake wetland complex from 2015 to 2023 reveals a dynamic ecosystem undergoing significant changes, influenced by both natural processes and anthropogenic factors. The integration of multiple remote sensing indices, SAR data, and land use/land cover analysis provides a comprehensive view of these changes, offering insights into the complex interplay between hydrology, vegetation, and human activities in this important wetland system.

Water body dynamics and hydrological changes

The fluctuations in water extent, as evidenced by the MNDWI, AWEI, and SAR-derived water masks, suggest a non-linear trend in the wetland’s hydrology. The initial expansion of water bodies from 2015 to 2019, followed by a slight contraction by 2023, could be attributed to various factors including climatic variations, changes in upstream water management, or alterations in local land use practices. This pattern aligns with findings from other studies on inland wetlands in semi-arid regions, where water extent can be highly variable due to seasonal and inter-annual climate fluctuations (Zhang et al., 2020). The observed changes underscore the vulnerability of the Manchar Lake system to both short-term weather patterns and longer-term climate trends, highlighting the need for adaptive management strategies.

Vegetation dynamics and ecosystem health

The dramatic increase in vegetation cover, particularly from 2019 to 2023, as shown by both the LULC analysis and vegetation indices (EVI, NDVI, GDVI, SAVI), indicates a significant shift in the wetland’s ecological character. This surge in vegetation, occurring simultaneously with a slight decrease in water extent, suggests a possible transition in parts of the wetland from open water to vegetated areas. Such transitions are not uncommon in shallow wetland systems and can be indicative of natural succession processes or responses to changing hydrological regimes (Zhu et al., 2019). The increase in scrub/shrub areas further supports this notion of ecological succession within the wetland complex.

However, the expansion of vegetation should be interpreted cautiously. While it may indicate improved wetland health in some aspects, it could also signal potential issues such as eutrophication or sedimentation, which can lead to increased plant growth at the expense of open water habitats (Junk et al., 2013). The observed changes necessitate further investigation into water quality parameters and nutrient dynamics within the system.

Anthropogenic influences and land use changes

The significant expansion of agricultural areas from 2015 to 2023 represents a major anthropogenic pressure on the Manchar Lake ecosystem. This trend aligns with global patterns of wetland conversion for agriculture, particularly in developing regions where food security is a pressing concern (Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 2018). The encroachment of croplands into wetland areas can have profound impacts on hydrology, water quality, and biodiversity, potentially altering the ecosystem services provided by the wetland (Verhoeven & Setter, 2010).

Interestingly, the decrease in built-up areas from 2019 to 2023 contradicts typical urbanization trends seen in many wetland-adjacent areas globally. This unexpected finding warrants further investigation and may reflect local land use policies, economic factors, or data classification nuances.

Topographic influence and wetland resilience

The analysis of topographic factors, particularly the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), provides crucial context for understanding the spatial distribution and resilience of wetland features within the Manchar Lake complex. Areas with high TWI values, corresponding to low-lying regions with high potential for water accumulation, show strong correlation with persistent wetland features across the study period. This topographic influence likely contributes to the wetland’s resilience in the face of hydrological fluctuations, maintaining core wetland areas even as peripheral zones experience more significant changes.

Implications for conservation and management

The observed dynamics in the Manchar Lake wetland complex highlight the need for integrated conservation and management approaches. The expansion of agriculture, while important for local livelihoods, must be balanced against the need to maintain wetland ecosystem functions. Implementing buffer zones, promoting sustainable agricultural practices, and exploring nature-based solutions for water management could help mitigate negative impacts on the wetland.

The fluctuations in water extent and vegetation cover underscore the importance of maintaining environmental flows and considering climate change impacts in multi-year changes management plans. Adaptive management strategies, informed by continued monitoring using remote sensing techniques, will be crucial for maintaining the ecological integrity of the Manchar Lake system.

Future research directions

-

1.

While this study provides valuable insights into the recent dynamics of the Manchar Lake wetland, several areas warrant further investigation:

-

2.

Long-term hydrological modeling to understand the impacts of climate change and water management practices on wetland hydrology.

-

3.

Detailed vegetation surveys to assess changes in species composition and potential invasive species spread.

-

4.

Water quality assessments to evaluate the impacts of agricultural expansion on wetland ecosystems.

-

5.

Socio-economic studies to understand the drivers of land use change and their implications for wetland conservation.

Future studies would benefit from more frequent or continuous data collection to capture potential fluctuations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the wetland’s dynamics. This could include annual observations or even seasonal monitoring to capture intra-annual variations.

Although our three time points cannot capture continuous trends, they provide valuable insights into the state of the Manchar Lake wetland at key moments over an eight-year period. These snapshots allow us to observe significant changes in wetland extent and characteristics, which can inform management decisions and highlight areas for more detailed investigation.

Conclusion

This comprehensive study of the Manchar Lake wetland complex from 2015 to 2023, utilizing multiple remote sensing techniques and indices, reveals a dynamic ecosystem undergoing significant changes. Our findings highlight non-linear trends in water extent, remarkable increases in vegetation cover, and substantial land use changes, particularly agricultural expansion. The integration of optical and SAR data, along with various spectral indices, proved highly effective in capturing these complex dynamics. Topographic analysis, especially through the Topographic Wetness Index, provided crucial insights into the spatial distribution and resilience of wetland features. While the wetland complex demonstrates resilience in maintaining core areas, it faces significant challenges from anthropogenic pressures and potential climate impacts. These observations underscore the need for adaptive management strategies, continuous monitoring, and integrated approaches that balance ecological conservation with human needs. The study provides a solid foundation for informed decision-making and emphasizes the importance of sustainable management practices. Moving forward, long-term hydrological modeling, detailed vegetation assessments, water quality monitoring, and socio-economic studies will be crucial to further enhance our understanding and ensure the long-term health and functionality of this vital ecosystem. The Manchar Lake wetland complex, with its demonstrated dynamism and ecological significance, represents a critical area for ongoing research and conservation efforts in the face of global environmental change.

Data availability

Data available upon request to corresponding author.

References

Aslam, R. W. et al. Wetland Identification through Remote sensing: insights into wetness, greenness, Turbidity, temperature, and changing landscapes. Big Data Res. 35, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdr.2023.100416 (2024).

Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Global Wetland Outlook. Gland, Switzerland: Ramsar Convention. 1–84 (2018).

Aslam, R. W. et al. Machine learning-based Wetland Vulnerability Assessment in the Sindh Province Ramsar Site using Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 13, 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13163294 (2024).

Amani, M. et al. Forty years of Wetland Status and trends analyses in the Great Lakes using Landsat Archive Imagery and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153778 (2022).

Mirakbari, M. & Ebrahimi-Khusfi, Z. Evaluation of the Climate Change effects on the Future Drought characteristics of Iranian wetlands. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 2167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-021-08486-1 (2021).

Khatik, N. Wetland creation restoration, and conservation. pp. 17–26. (2022).

Kalhoro, N. A. et al. Vulnerability of the Indus River Delta of the North Arabian Sea, Pakistan. Glob Nest J. 18, 599–610. https://doi.org/10.30955/gnj.001912 (2016).

Khan, A. & Arshad, S. Wetlands of Pakistan: distribution, degradation and management. Pakistan Geogr. Rev. 69, 28–45 (2014).

Gao, Y. et al. Feasibility of Estimating Heavy Metal Concentrations in Wetland Soil Using Hyperspectral Technology. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS); IEEE, July 2017; pp. 4886–4889. (2017).

Adam, E., Mutanga, O. & Rugege, D. Multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing for identification and mapping of Wetland Vegetation: a review. Wetl Ecol. Manag. 18, 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-009-9169-z (2010).

Zhipeng, G., Jiang, W., Peng, K., Deng, Y. & Wang, X. W. Mapping and Landscape Analysis for Supporting International Wetland Cities: Case studies in Nanchang City and Wuhan City. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 16, 8858–8870. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3302031 (2023).

Guo, M., Li, J., Sheng, C., Xu, J. & Wu, L. A. Rev. Wetland Remote Sens. Sens. 17, 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17040777 (2017).

Wu, C. et al. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Construction and Application of the Diagnostic Indicator System of Wetland Health Based on Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the (IGARSS); IEEE, July 2016; pp. 7176–7179. (2016).

Luo, C., Hao, M., Li, Y. & Tong, L. Monitoring the Changes of Wetlands in the Source Region of Three Rivers with Remote Sensing Data from 1976 to 2013. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Workshop on Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Applications (EORSA); IEEE, July ; pp. 198–201. (2016).

Amler, E., Schmidt, M. & Menz, G. Definitions and mapping of East African wetlands: a review. Remote Sens. 7, 5256–5282. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs70505256 (2015).

Liu, D. et al. Development of a Landscape-based Multi-metric Index to Assess Wetland Health of the Poyang Lake. Remote Sens. 14, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14051082 (2022).

Fouad, G. & Lee, T. M. A spatially distributed Groundwater Metric for describing hydrologic changes in a Regional Population of wetlands North of Tampa Bay, Florida, from 1990 to 2015. Wetlands. 41, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-021-01502-w (2021).

Ma, Z., Chen, W., Xiao, A. & Zhang, R. The susceptibility of Wetland areas in the Yangtze River Basin to temperature and vegetation changes. Remote Sens. 15, 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15184534 (2023).

Lang, M. W., Bourgeau-Chavez, L., Tiner, R. W. & Klemas, V. V. Remote Sensing of Wetlands; Tiner, R.W., Lang, M.W., Klemas, V. V., Eds.; CRC Press, ISBN 9781482237382. (2015).

Jiang, B. et al. Ecosystem services valuation of the Haihe River Basin Wetlands. Shengtai Xuebao/ Acta Ecol. Sin. 31, 2236–2244 (2011).

Lyon, J. G., Lopez, R. D., Lyon, J. G., Lyon, L. K. & Lopez, D. K. Wetland Landscape Characterization; CRC Press, ISBN 9781420022681. (2001).

Moreira, A. et al. A Tutorial on Synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 1, 6–43. https://doi.org/10.1109/MGRS.2013.2248301 (2013).

Slagter, B., Tsendbazar, N. E., Vollrath, A. & Reiche, J. Mapping wetland characteristics using temporally dense sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 data: a case study in the St. Lucia Wetlands, South Africa. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 86, 102009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2019.102009 (2020).

Whyte, A., Ferentinos, K. P. & Petropoulos, G. P. A New Synergistic Approach for Monitoring wetlands using sentinels – 1 and 2 data with object-based machine learning algorithms. Environ. Model. Softw. 104, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2018.01.023 (2018).

Mahdianpari, M. et al. Large-scale change monitoring of wetlands using Time Series Landsat Imagery on Google Earth Engine: a Case Study in Newfoundland. GIScience Remote Sens. 57, 1102–1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2020.1846948 (2020).

Muro, J., Strauch, A., Fitoka, E., Tompoulidou, M. & Thonfeld, F. Mapping Wetland Dynamics with SAR-Based change detection in the Cloud. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16, 1536–1539. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2019.2903596 (2019).

Du, B. et al. Mapping Wetland Plant communities using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral imagery by comparing Object/Pixel-Based classifications combining multiple machine-learning algorithms. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 14, 8249–8258. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3100923 (2021).

Peng, H. et al. Monitoring spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Wetland Vegetation and their response to hydrological conditions in a Large Seasonal Lake with Time Series Landsat Data. Ecol. Indic. 142, 109283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109283 (2022).

Garba, S. I., Ebmeier, S. K., Bastin, J. F., Mollicone, D. & Holden, J. Wetland Mapping at 10 m resolution reveals Fragmentation in Southern Nigeria. Wetl Ecol. Manag. 31, 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-023-09919-2 (2023).

Alho, C. & Silva, J. Effects of severe floods and droughts on Wildlife of the Pantanal Wetland (Brazil)—A review. Animals. 2, 591–610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani2040591 (2012).

Verones, F., Bartl, K., Pfister, S., Jiménez Vílchez, R. & Hellweg, S. Modeling the local biodiversity impacts of agricultural water use: case study of a wetland in the coastal arid area of Peru. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4966–4974. https://doi.org/10.1021/es204155g (2012).

Aslam, R. W. et al. Monitoring landuse change in Uchhali and Khabeki Wetland Lakes, Pakistan using remote sensing data. Gondwana Res. 129, 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2023.12.015 (2024).

Shafi, A., Chen, S., Waleed, M. & Sajjad, M. Leveraging machine learning and remote sensing to Monitor Long-Term spatial-temporal Wetland changes: towards a National RAMSAR Inventory in Pakistan. Appl. Geogr. 151, 102868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102868 (2023).

Zhu, J. Q., Yu, H. & He, Q. Y. Development of Wetland Agriculture and Its Prospect. In Proceedings of the 2013 Third International Conference on Intelligent System Design and Engineering Applications; IEEE, January ; pp. 596–601. (2013).

Mahdavi, S. et al. Remote sensing for Wetland classification: a Comprehensive Review. GIScience Remote Sens. 55, 623–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2017.1419602 (2018).

Xu, T. et al. Wetlands of international importance: status, threats, and future protection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101818 (2019).

Wang, M. et al. Annual wetland mapping in metropolis by temporal sample migration and random forest classification with time series landsat data and google earth engine. Remote Sens. 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14133191 (2022).

DeLancey, E. R. et al. Creating a detailed wetland inventory with sentinel-2 time-series data and google earth engine in the prairie pothole Region of Canada. Remote Sens. 14, 3401. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14143401 (2022).

Feyisa, G. L., Meilby, H., Fensholt, R. & Proud, S. R. Automated water extraction index: a new technique for surface water mapping using landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 140, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.08.029 (2014).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00096-2 (2002).

Sripada, R. P., Heiniger, R. W., White, J. G. & Meijer, A. D. Aerial Color Infrared Photography for determining early In-Season Nitrogen requirements in Corn. Agron. J. 98, 968–977. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2005.0200 (2006).

Xu, H. Modification of normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI) to Enhance Open Water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 27, 3025–3033. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431160600589179 (2006).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic Infrared Linear combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8, 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(79)90013-0 (1979).

Huete, A. A. & Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 25, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(88)90106-X (1988).

Beven, K. J., Kirkby, M. J. A. & Physically Based Variable contributing area model of Basin Hydrology / Un Modèle à Base Physique De Zone D’appel Variable De L’hydrologie Du Bassin Versant. Hydrol. Sci. Bull. 24, 43–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667909491834 (1979).

Small, D. Flattening Gamma: Radiometric Terrain correction for SAR Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 49, 3081–3093. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2011.2120616 (2011).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random Forest in Remote sensing: a review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 114, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.01.011 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R561), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This work is supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R561), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: WC, RWA, AQ, and IN.: Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation, formal analysis; investigation; WC, AQ, IN, AT & AS.: resources; IN, WC, SU, AS, WS, KFA and AT.: data curation; AT, KFA, WC, SU, WS and IN; writing original draft preparation.; RWA, WC, WS, KFA, IN and AT.: writing review and editing; visualization, RWA and AT.; supervision, WS and KFA; project administration, WS and KFA.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaoyong, W., Aslam, R.W., Quddoos, A. et al. SAR image integration for multi-temporal analysis of Lake Manchar Wetland dynamics using machine learning. Sci Rep 14, 26669 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76730-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76730-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spatio-temporal analysis of urban expansion and land use dynamics using google earth engine and predictive models

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The geographical evolution of sports cultural landscapes in historical and cultural research

GeoJournal (2025)

-

Virtual reality reconstructions of lost cultural landscapes: digital heritage preservation methods

GeoJournal (2025)

-

Machine learning assessment of CMIP6 projected maximum temperature and precipitation impacts on crop yields and rangeland productivity in Pakistan

GeoJournal (2025)

-

Remote sensing-based flash flood mapping and damage assessment in Dera Ismail Khan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)