Abstract

This study evaluated the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the “Motivational Climate in Physical Education Scale” (MCPES) among middle school students. Data were collected from 1,008 students, with 473 completing the MCPES, the Physical Needs Support in Physical Education Scale (PNS-PE), and the Youth Sports Friendship Quality Scale (YSFQS). Additionally, 437 students completed only the MCPES, and 200 valid retest questionnaires were gathered three weeks later. Exploratory factor analysis identified four factors: perceived mastery climate, perceived performance climate, perceived autonomy support, and perceived relatedness support with a total of 16 items. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the four-factor structure (χ2/df = 3.38, GFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.05). The scale exhibited strict measurement invariance across genders and strong invariance across grade levels. It was positively correlated with teacher autonomy support (r = 0.34–0.53) and with each dimension and total score of sports friendship (r = 0.21–0.61). Cronbach’s α coefficients for the MCPES and its dimensions were 0.75, 0.82, 0.79, 0.80, and 0.88, respectively. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the three-week retest were 0.64, 0.63, 0.72, and 0.76. In conclusion, the Chinese version of the MCPES demonstrates robust reliability and validity for use with middle school students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Classroom teaching occurs in a specific environment, which at the macro level includes both the physical and psychological teaching environments1. The state of the classroom atmosphere reflects the condition of the psychological environment. Unlike other academic settings, physical education (PE) combines physical activity, competition, and collaboration, creating a unique motivational climate that directly influences students’ emotional, social, and psychological experiences2,3. The 2022 edition of the Physical Education and Health Curriculum Standards in China emphasizes the reform of teaching methods, urging a shift toward a “student-centered” approach. This involves updating teaching processes and creating dynamic, engaging contexts that combine interaction, communication, and practical application4. The classroom atmosphere is a comprehensive topic that involves multiple disciplines such as pedagogy, educational sociology, and psychology5. Over the past few decades, Achievement Goal Theory (AGT)6 and Self-Determination Theory (SDT)7 have explored how to create a positive classroom atmosphere from a psychological perspective of motivation, deepening research in this field and becoming a major focus of study. AGT posits that the motivational climate is influenced by social factors in the individual’s environment, such as teachers, coaches, parents, and peers, and is shaped by the achievement goals set in specific activities. According to Epstein and Ames, the motivational climate is defined by six dimensions (TARGET): Task, Authority, Reward, Grouping, Evaluation, and Time. Therefore, the teaching behavior of physical education teachers can influence students’ orientations. Specifically, according to AGT, when students are in a master-oriented environment, success is defined by personal effort, and personal progress, skill development, and learning new abilities are encouraged. However, in a performance-oriented environment, success is defined by comparing one’s performance to others, fostering a sense of superiority over peers. Morgan et al.5 redefined the motivational climate from an interdisciplinary perspective, emphasizing the inclusion of “Relationship” into the TARGET framework, as relationships are critical to fostering effective student motivation. SDT posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are key factors influencing individual mental health and social well-being. Environments that satisfy these needs positively impact well-being. Conversely, environments that restrict the fulfillment of these needs can negatively affect human functioning and well-being. All three needs are essential, and if any are unmet, detrimental motivational outcomes may result7,8. Previous studies have shown that integrating AGT6and SDT7 helps to understand students’ intrinsic motivation, as both involve social and cognitive factors. The main distinction between the two theories is that AGT focuses solely on competence, dividing it into master-oriented and performance-oriented types. Although SDT also addresses competence, it includes two additional cognitive elements: autonomy and relatedness. These two theories approach competence from different perspectives. In AGT, competence can be described as the driving force of behavior6. In SDT, competence is a factor that meets individual needs, influencing subsequent beliefs, emotions, and behaviors7,9.

Developing a valid and reliable scale is crucial for analyzing the motivational climate in PE classes. Such a scale can benefit physical education teachers by helping them assess how their teaching behavior affects the motivational climate. International motivational scales are generally based on AGT. Prominent examples include the Learning and Performance Orientation in Physical Education Questionnaire (LAPOPEQ)10 and the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire (PMCSQ)11. The PMCSQ has been widely applied and validated in adolescent populations, showing high reliability and validity12. These scales are primarily based on AGT’s two dimensions of perceived competence. However, SDT’s concepts of autonomy and relatedness are either overlooked or subsumed within these two dimensions. Soini et al.,13 following the recommendations of Duda and Balaguer14, integrated SDT and AGT into a new framework to develop the MCPES. This scale enhances the theoretical framework by addressing four dimensions related to the environment that satisfy three psychological needs: perceived relatedness, perceived autonomy, perceived master -climate, and perceived performance climate. The last two dimensions reflect perceptions of competence. This scale has been widely used in various countries and regions and has demonstrated cross-cultural consistency15,16.

Empirical research on motivational climate in physical education classes in China is still relatively limited, and research tools are scarce. Some studies have examined the role of autonomy support17 and relatedness support18 in promoting middle students’ intrinsic motivation in these settings. However, a comprehensive, theory-driven, multidimensional measurement tool has yet to be developed. This gap in robust tools impedes a full understanding of the motivational climate in PE classrooms. Research into the adaptability of such climates in Chinese physical education can substantially advance the field. To address this, we plan to introduce MCPES into Chinese physical education classrooms, filling the current gap in measurement tools for assessing motivational climate. In summary, we propose the following research questions: Can the MCPES maintain the same factor structure as the original scale within the Chinese cultural context? What are the internal consistency, reliability, and cross-cultural applicability of the Chinese version of MCPES? Accordingly, Hypothesis 1 is proposed: The Chinese version of MCPES will demonstrate high internal consistency and reliability across four dimensions—mastery climate, performance climate, autonomy support, and relatedness support.

The Chinese educational system, similar to that of many other countries, is structured into 6 years of elementary education and 3 years of middle school education. As students transition into middle school, they experience substantial changes in attention19 and emotional regulation20, which can impact the classroom environment both positively and negatively. Throughout middle school, students not only face higher academic demands but must also adapt to evolving classroom norms, shifting teacher-student dynamics, and changing peer interactions. This period represents a critical phase of adolescent development, during which students’ self-awareness, academic self-concept, and self-esteem are particularly susceptible to fluctuations due to changes in the school and classroom environments. Research suggests that students’ self-perceptions of social competence tend to improve following their transition into seventh grade21. A study by Chai & Wu on Chinese middle school students explored grade and gender differences in sources of enjoyment and exercise motivation22. They found that compared to 7th graders, 8th and 9th graders reported significantly lower levels of enjoyment and exercise motivation. Additionally, boys exhibited significantly higher exercise motivation intensity compared to girls. Based on these developmental changes, we pose the following question: Can the introduced scale maintain measurement stability and consistency across different grade levels and gender groups? To address this inquiry, we propose Hypothesis 2: The Chinese version of the MCPES will demonstrate measurement invariance across grade levels and gender groups.

Participant

Boateng et al. proposed a three-phase, nine-step framework for scale development and revision23. They suggested that the revision process could be streamlined to the last several steps: factor analysis, structural validity testing, and reliability assessment. To enhance the robustness of the sample, the study recommended using different samples for scale development and validation. Accordingly, this study will employ four distinct samples to conduct item comprehensibility, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and reliability testing.

Given that the original scale was designed for ninth-grade students, this study expanded its applicability to cover students from seventh to ninth grade. We selected seventh-grade students to assess item comprehensibility. To further enhance the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, we conducted analyses using student samples from various regions. Research indicates that the sample size EFA should be 5–10 times the number of items on the scale24, and CFA requires a minimum of 200 cases25. Given that this study also includes an evaluation of gender and grade invariance, the sample sizes for both exploratory and confirmatory analyses were set at no less than 400 participants to ensure the robustness of the analysis.

Sample 1: Using purposive sampling, 20 seventh-grade students from a general school in Shandong Province, China were selected to complete the Chinese version of MCPES questionnaire. The sample was evenly divided by gender and comprised students with relatively weaker reading comprehension skills as nominated by their Chinese language teacher.

Sample 2: Convenient sampling was used to select 437 middle school students from two schools in Shandong Province, China to complete the Chinese version of MCPES questionnaire. This sample included 205 boys and 232 girls, with 178 -seventh-grade students, 132 - eighth-grade students, and 127 ninth-grade students, aged 12.82 ± 1.13 years.

Sample 3: Convenient sampling was used to select 473 middle school students from two schools in Chongqing, China to complete the MCPES and criterion-related questionnaires. The sample included 225 boys and 248 girls, with 323 seventh-grade students, 96 eighth-grade students, and 54 t ninth-grade, aged 12.56 ± 1.05 years.

Sample 4: A follow-up test was conducted after two months with 78 students from Sample 2, including 42 boys and 36 girls.

Measures

Motivational climate in Physical Education Scale (MCPES)

Developed by Soini and colleagues13, the MCPES contains 18 items, divided into four factors: perceived mastery climate, perceived performance climate, perceived autonomy support, and perceived relatedness support. Respondents rate the items on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represent “strongly disagree” and 5 represent “strongly agree.”

The MCPES was translated into Chinese using the translation-back translation method. Four university teachers, each holding the Test for English Majors Band 8 (TEM-8) certificate, were responsible for the translation: two for the forward translation and two for the back translation. It is worth noting that two of the translators were professional English teachers from sports universities, and the other two were English teachers actively engaged in middle school teaching. As mentioned earlier, some MCPES items might not be appropriate for middle school students. Therefore, based on the forward and back translations, feedback from four experienced middle school teachers (each with over 12 years of teaching experience) was incorporated.

Validity testing tools

Boateng et al. categorized criterion validity into two types: predictive validity and concurrent validity23. To assess criterion validity in this study, we utilized Sample 3 and employed the concurrent validity approach by selecting the Youth Sports Friendship Quality Scale (YSFQS)26 and the Perceived Needs Support in Physical Education Scale (PNS-PE)27. The YSFQS assesses students’ social interactions and emotional experiences during physical activities, examining the relationship between the motivational climate and the quality of peer interactions. The PNS-PE, grounded in SDT, measures the support for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom, evaluating how the motivational climate influences the fulfillment of students’ psychological needs. Both scales have been extensively validated and widely applied in China, demonstrating strong reliability and validity28. We anticipate significant positive correlations between relevant dimensions of these scales and the motivational climate in physical education settings, thereby confirming the criterion-related validity of the scale.

YSFQS: The version of the scale revised by Zhu et al.26 in 2010 was utilized in this study. To better align with the context of physical education classes, the terms “competition” and “training” in the original scale were replaced with “practice.” This scale comprises six dimensions: Common Interests and Communication (9 items), Conflict Resolution (3 items), Positive Personal Qualities (3 items), Companionship and Sports Enjoyment (4 items), Self-Esteem Enhancement (3 items), and Sport Support (3 items), making up a total of 25 items. Responses are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree.” (5) The scale demonstrated an internal consistency coefficient of 0.98 in this study.

PNS-PE: This questionnaire, originally developed by Williams and Deci (1996)27 and later revised into Chinese by Xiang (2014)29, contains 15 items across three dimensions: Autonomy Support (6 items), Competence Support (4 items), and Relatedness Support (5 items). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree.” (5) In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the scale was 0.92.

Procedure

Convenience cluster sampling was used to select students from grades 7–9 in six middle schools in Shandong Province and Chongqing City as participants. The study began by communicating with the principals of the six schools via phone or in-person meetings to explain the purpose and significance of the research. Four schools agreed to participate in the study. After obtaining school approval, informed consent from parents and/or legal guardians has been obtained.

The study was approved by the Capital Sports Ethics Committee, and all methods were conducted following relevant guidelines and regulations. Data were collected using the Wenjuanxing platform. As the primary investigator, I trained the homeroom and PE teachers on how to administer the questionnaire, ensuring they were familiar with the instructions and key considerations. Students completed the questionnaires during PE class in the school’s computer lab. For those unable to complete the survey at school, the questionnaire was disseminated by their homeroom teachers through the same platform for independent completion at home. To maintain consistency and reliability, participants were able to access support for any queries related to the questionnaire through designated communication channels, including a dedicated email address or phone number, thereby ensuring standardized responses. All questionnaire items were presented in a random order to mitigate potential sequence, proximity, and priming effects.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 and Amos 24.0. Data from Sample 1 were used to test item comprehensibility (participants rated items as “understood” or “not understood”). Data from Sample 2 were used for common method bias testing, item analysis, and EFA. Data from Sample 3 were used for CFA, equivalence testing, and criterion-related validity testing. Data from Sample 4 were used to test 2-month retest reliability. Internal Consistency Reliability: According to Nunally (1978)30, a Cronbach’s α coefficient > 0.9 indicates excellent reliability, 0.7 < α < 0.9 indicates high reliability, 0.35 < α < 0.7 indicates moderate reliability, and α < 0.35 indicates low reliability. In practice, a Cronbach’s α greater than 0.7 is commonly used as the standard.

Results

Item comprehensibility testing

Twenty middle school students with relatively weaker reading abilities indicated that they understood all 18 items of the Chinese MCPES, suggesting that the items are comprehensible to most middle school students and suitable for larger-scale administration.

Common method bias testing

Since data collection was solely through self-report, common method bias was considered. Necessary controls, such as the examiner, time, location, order, and anonymity, were applied during the testing process, and the Harman single-factor test was used for further statistical control. Results showed that the first factor accounted for 24.46% of the variance, below the critical value of 40%, indicating that common method bias is not a serious concern in this study31.

Item analysis

Item analysis was conducted using Sample 2, and evaluated based on item-total correlations. Results showed that the correlation coefficients between the 18 items and the total score ranged from 0.503 to 0.609 (p < 0.001). Critical ratio analysis was then performed, with the highest 27% of total scores classified as the high group and the lowest 27% as the low group. An independent samples t-test revealed significant differences across 18 items (P < 0.001). These results suggest that the Chinese version of the MCPES has high discriminatory power (Table 1).

Validity testing

Construct validity

EFA was performed on the Chinese version of MCPES using data from Sample 2. Results showed that the KMO value was 0.898 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded χ2(153) = 3276.98, P < 0.001, indicating that factor analysis was appropriate.

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation revealed that three factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining a total of 52.57% of the variance. The analysis indicated that two items (6 and 13) exhibited cross-loadings on multiple factors, with a difference in loadings of less than 0.20, leading to their removal. Based on the 4-factor structure from previous research and theoretical considerations, four factors were retained. EFA was then performed on the remaining 16 items in the sample. The eigenvalues were 5.36, 3.00, 1.17, 0.83 with a cumulative variance explained rate of 64.72%. Factor loadings ranged from 0.51 to 0.85. Based on the content of the factors and corresponding items (see Table 2), the factors were named perceived mastery climate, perceived performance climate, perceived autonomy support, and perceived relatedness support.

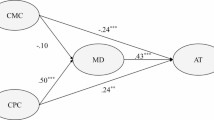

Data from Sample 3 were used to perform CFA on the four-factor structure of the Chinese version of the Motivational Climate in Physical Education Scale, See Fig. 1. The results showed that the factor loadings ranged from 0.63 to 0.81, and the model fit was good (χ2/df = 3.38, GFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.93).

Measurement invariance testing

Measurement invariance testing was conducted on Sample 3 by constructing multiple group models to examine whether the Chinese version of the MCPES demonstrates invariance across gender and grade levels. The results are detailed in Table 3. In the morphological equivalence test, the model fit was deemed acceptable, meeting the criteria for further invariance analysis. Building on this model, factor loadings, intercepts, and residuals were constrained to be equal successively.

For the gender group, the differences in CFI, TLI, and RMSEA (ΔCFI, ΔTLI, ΔRMSEA) between the morphological and weak invariance models, the weak and strong invariance models, and the strong and strict invariance models were all less than 0.01. This indicates that strict invariance across genders was established for the Chinese version of MCPES.

For the grade level group, the differences in CFI, TLI, and RMSEA (ΔCFI, ΔTLI, ΔRMSEA) between the morphological and weak invariance models, as well as between the weak and strong invariance models, were all less than 0.01. However, the ΔCFI between the strong and strict invariance models was 0.018, indicating moderate differences32, suggesting that strong invariance across grade levels was established for the Chinese version of MCPES.

Criterion validity

Criterion-related validity was assessed using Pearson correlation analysis based on Sample 3, incorporating scores from the MCPES,. PNS-PE, and YSFQS. The results in Table 4 show that the total score and each dimension of the MCPES were significantly positively correlated with both PNS-PE and YSFQS.

Reliability testing

For Sample 2, Cronbach’s α coefficients for autonomy support, relatedness support, mastery climate, performance climate, and the overall scale were 0.72, 0.84, 0.81, 0.89, and 0.86, respectively. For Sample 3, the corresponding Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.75, 0.82, 0.79, 0.80, and 0.88.

Test-Retest Reliability: Although motivational climate has contextual characteristics, it is also a relatively stable trait. Therefore, in this study, the MCPES was retested after a 2-month interval to examine test-retest reliability. For Sample 4, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the overall scale was 0.76. The ICCs for perceived autonomy support, perceived relatedness support, perceived master climate, and perceived performance climate were 0.64, 0.63, 0.72, and 0.70, respectively.

Discussion

This study targeted middle school students and conducted a preliminary revision of the widely used MCPES. The findings suggest that the Chinese version of the MCPES exhibits strong structural validity, reliability, and measurement invariance across both gender and grade levels. These results support Hypothesis 1, confirming that the Chinese MCPES demonstrates high internal consistency and reliability across the four dimensions: perceived mastery climate, perceived performance climate, perceived autonomy support, and perceived relatedness support.In terms of content validity, since the original MCPES was designed for middle school students aged 14–15, this study expanded the target group to include all middle school students aged 12–15. To verify the suitability of the scale items for this age group, 20 seventh-grade students (aged 12–13) with relatively weaker reading abilities were selected to analyze the content of the 18 translated items. Some translated items were further refined to better fit the Chinese context without altering the original meaning. For example, in item 7, the initial translation was “During practice in class, our goal in PE is to achieve unity.” However, this item aimed to emphasize the perception of peer support during class. Although the translation was relatively accurate, it did not fully capture the item’s intent. Therefore, it was revised to “During PE class, we unite and practice together.” After revision, all items were understandable to the majority of middle school students. Item analysis results indicated that the Chinese version of the MCPES, consisting of 18 items, demonstrated good item discrimination, with high consistency between individual items and the total score.

Regarding construct validity, EFA revealed that items 6 and 13 exhibited cross-loadings on two or more factors, with cross-loading differences less than 0.20, leading to their removal. The remaining items produced four dimensions consistent with the theoretical framework proposed by Soini et al., based on SDT and AGT13. The results of the CFA indicated that the four-factor structure of the Chinese version of the MCPES demonstrated good model fit, suggesting good stability. This structure was consistent with both the original13 and the Greek version16 of the scale.

Additionally, this study conducted measurement invariance testing across gender and grade levels for the Chinese version of MCPES by constructing multi-group models. The results support Hypothesis 2, demonstrating that strict invariance across gender and strong invariance across grade levels were achieved for the revised MCPES. This confirms its suitability and reliability for use across different gender and grade groups among middle school students, further validating its broader applicability.

Correlation analysis between the total score and four dimensions of the Chinese version of MCPES and the criterion variables revealed significant positive correlations between the mastery climate, autonomy support, and relatedness support dimensions of the MCPES and PNS-PE and its sub-dimensions. The evaluation of teaching goals and the reward processes set by teachers largely determine whether the classroom motivational climate is mastery-oriented or performance-oriented. Teacher-provided need support fosters a lively and proactive classroom atmosphere, which in turn enhances students’ perceptions of mastery climate, autonomy support, and relatedness support, consistent with previous research findings18,33.

However, an interesting finding of this study is the significant positive correlation between perceived performance climate in MCPES and the dimensions of need support, which contrasts with some earlier studies. Some research has distinguished between performance climates driven by teachers and those driven by students34,35. These studies found that a teacher-driven performance climate was negatively associated with basic psychological need satisfaction, while a peer-driven performance climate showed a significant positive relationship with need satisfaction. The peer-driven performance climate may encourage positive engagement and autonomous choices in competitive environments, whereas a teacher-driven performance climate could increase stress and anxiety, potentially undermining the satisfaction of relatedness needs. Notably, all four items in this study related to students’ perceptions of competition among peers, suggesting that peer competition may contribute to a more positive classroom climate. Currently, there is limited research investigating the effects of both teacher- and peer-driven performance climates on student learning outcomes. Future studies should aim to explore this area more comprehensively, providing stronger empirical evidence to clarify the specific impact of these climates on classroom motivation and engagement.

Furthermore, the total score and dimensions of the MCPES were significantly positively correlated with the YSFQS and its dimensions, consistent with previous studies36,37,38. Peers may influence achievement motivation by creating specific motivational climates. For example, Wentzel et al.39 found that through cooperative learning activities, peers held each other accountable for certain behaviors, provided help, and shared knowledge, which contributed to the formation of a master-involved climate. The results of the Chinese version of MCPES showed good consistency and temporal stability, indicating that the scale has good reliability among Chinese middle school students. It can be used to assess the motivational climate in PE classes and provide a new tool for evaluating PE instruction.

This study offers a valuable tool for future research on motivational climates in PE. Since motivational climate significantly impacts students’ classroom performance and psychological development, localizing measurement tools is essential for a deeper understanding of sports motivation among Chinese students. This tool provides crucial insights for developing and evaluating future teaching strategies. For instance, Ahmadi et al. (2023)40 created a classification system for teacher motivational behaviors grounded in SDT, featuring 57 behaviors aligned with SDT principles. Given the extensive range of motivational behaviors, implementing effective interventions presents significant challenges. Future research could utilize the MCPES to assess the effectiveness of these behaviors and identify more representative indicators, thereby making interventions to enhance motivational climates in PE more feasible, particularly within the Chinese educational context.

Furthermore, there is a scarcity of effective measurement tools for sports motivation in the Chinese context. Current research tends to examine individual aspects of the motivational climate, such as autonomy support29 and relatedness support41, with less focus on the synergistic effects of multiple factors within the classroom environment. This limitation results in an incomplete capture of the various factors influencing students’ sports motivation, leading to a fragmented understanding of their motivational states. Therefore, applying a localized version of MCPES will facilitate more comprehensive research on sports motivation, offer a thorough understanding of student motivation, and support the development of scientifically based interventions to improve the motivational climate in PE classrooms.

Strengths, limitations, and future research directions

The primary strength of this study lies in its integration of SDT and AGT to create a more comprehensive tool for assessing the motivational climate in PE classrooms. By revising the MCPES and extending its applicability to students in grades 7 to 9, the study demonstrates the scale’s cross-grade applicability. Additionally, the cultural adaptation of the scale ensures its relevance and reliability within the context of Chinese middle school students. The results validate the structural validity and measurement invariance of the scale, indicating high internal consistency and cross-cultural applicability.

Although data were collected from students across multiple regions in China, the sample does not fully represent the national student population, particularly excluding rural and special student groups. This limitation may impact the external validity of the findings, restricting the generalizability of the results to broader student populations. Furthermore, the deletion of certain items due to cross-loading, while improving the scale’s reliability and validity, may result in the loss of key information, particularly lacking items that capture the perception of performance climate from the teacher. This absence potentially weakens the interpretive power of the scale. Lastly, the criterion-related validation relied heavily on self-report measures, which are susceptible to social desirability bias, as students may provide idealized responses, thereby affecting the accuracy of the results.

Future studies should expand the sample size to include a wider variety of student groups, enhancing the generalizability and representativeness of the scale. Incorporating classroom observations, teacher evaluations, and objective measures of physical activity could further validate the scale’s effectiveness, minimizing bias from self-reports. In addition, adding items that capture teacher-driven performance climate will provide a more holistic view of the classroom motivational environment and improve the scale’s explanatory power. Longitudinal research could also be conducted to track changes in student motivation across academic years, evaluating the long-term stability and predictive validity of the MCPES, thereby offering more timely insights for instructional interventions and further advancing research on motivational climates in PE classrooms.

Data availability

The dataset used during the current study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Wang, S. H. A glimpse into Research on Classroom Atmosphere. Educ. Explor. 37–38 (2007).

Gilbert, L. M. et al. Effects of a games-based physical education lesson on cognitive function in adolescents. Front. Psychol. 14, (2023).

Garn, A. C., Simonton, K., Dasingert, T. & Simonton, A. Predicting changes in student engagement in university physical education: application of control-value theory of achievement emotions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 29, 93–102 (2017).

Ji, L. Interpretation of the national standard for physical education and health curriculum. China Sport Sci. 42, 3–17 (2022).

Morgan, K. Reconceptualizing Motivational Climate in Physical Education and Sport Coaching: an interdisciplinary perspective. Quest. 69, 95–112 (2017).

Nicholls, J. G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education261 (Harvard University Press, 1989).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Contemp. Sociol. 3, (1985).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78 (2000).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Papaioannou, A. Development of a questionnaire to measure achievement orientations in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 65, 11–20 (1994).

Seifriz, J. J., Duda, J. L. & Chi, L. The relationship of perceived motivational climate to intrinsic motivation and beliefs about success in basketball. J. Sport Exerc. Psy. 14, 375–391 (1992).

Walling, M. D., Duda, J. L. & Chi, L. The Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire: construct and predictive validity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 15, 172–183 (1993).

Soini, M., Liukkonen, J., Watt, A., Yli-Piipari, S. & Jaakkola, T. Factorial validity and internal consistency of the motivational climate in physical education scale. J. Sport Sci. Med. 13, 137–144 (2014).

Duda, J. L. & Balaguer, I. Coach-Created Motivational Climate. in Social Psychology in Sport 117–130 (Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, US, doi: (2007). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781492595878.ch-009

Jaakkola, T., Wang, C. K. J., Soini, M. & Liukkonen, J. Students’ perceptions of Motivational Climate and Enjoyment in Finnish Physical Education: A Latent Profile Analysis. J. Sport Sci. Med. 14, 477–483 (2015).

Topatsi, A. et al. The motivational climate in Physical Education Scale (MCPES) in Greek educational context of elementary school: psychometric properties. AJHSSR. 05, 34–39 (2022).

Xiang, P., Gao, Z. & Chen, S. Instructional choices and student engagement in physical education. Asian J. Exerc. Sports Sci. 10, 90–97 (2013).

Koka, A. The effect of teacher and peers need support on students’ motivation in physical education and its relationship to leisure time physical activity. Acta Kinesiologiae Universitatis Tartuensis. 19, 48 (2013).

Cohen Kadosh, K., Heathcote, L. C. & Lau, J. Y. F. Age-related changes in attentional control across adolescence: how does this impact emotion regulation capacities? Front. Psychol. 5, 111 (2014).

Beaumont, J. et al. Students’ emotion regulation and School-Related Well-Being: longitudinal models juxtaposing between- and within-person perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 115, (2023).

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Mac Iver, D., Reuman, D. A. & Midgley, C. Transitions during early adolescence: changes in children’s domain-specific self-perceptions and general self-esteem across the transition to junior high school. Dev. Psychol. 27, 552–565 (1991).

Chai, J. & Wu, P. X. Analysis of the changes in sports enjoyment among adolescents in China and theoretical responses. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 46, 65–79 (2023).

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. & Young, S. L. Best practices for developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front. Public. Health. 6, 149 (2018).

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S. & Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol. Methods. 4, 84–99 (1999).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Ed. xvii, 534 (Guilford Press, New York, NY, US, 2016).

Zhu, Y., Guo, L. Y., Chen, P. & Xu, C. Construction of a model for peer relationships, exercise motivation, and behavioral engagement in adolescents. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport. 25, 218–223 (2010).

Williams, G. C. & Deci, E. L. Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self-determination theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 767–779 (1996).

Zhang, B. G. A study on the impact of interpersonal support on high school students’ sports participation in specialized physical education (Shanghai University of Sport, 2023).

Xiang, M. Q. The relationship between autonomy support in physical education and extracurricular exercise among adolescents: the mediating role of basic psychological needs. J. Sport Sci. 35, 96–100 (2014).

Nunally, J. C. Psychometric Theory 2nd edn (McGraw-Hill, 1978).

Zhou, H. & Long, L. R. Statistical tests and control methods for common method bias. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 942–950 (2004).

Wang, M. C. Latent Variable Modeling and Applications of Mplus: Basic Volume (Chongqing University, 2014).

Barkoukis, V. & Hagger, M. S. The trans-contextual model: perceived learning and performance motivational climates as analogues of perceived autonomy support. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28, 353–372 (2013).

Rodrigues, F., Monteiro, D., Teixeira, D. S. & Cid, L. The relationship between teachers and peers’ motivational climates, needs satisfaction, and Physical Education grades: an AGT and SDT Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 6145 (2020).

Rodrigues, F., Monteiro, D., Teixeira, D. & Cid, L. Understanding motivational climates in physical education classes: how students perceive learning and performance-oriented climates by teachers and peers. Curr. Psychol. 41, 5298–5306 (2022).

Cox, A., Duncheon, N. & McDavid, L. Peers and teachers as sources of relatedness perceptions, motivation, and affective responses in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 80, 765–773 (2009).

Ntoumanis, N., Taylor, I. M. & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. A longitudinal examination of coach and peer motivational climates in youth sport: implications for moral attitudes, well-being, and behavioral investment. Dev. Psychol. 48, 213–223 (2012).

Ntoumanis, N. & Vazou, S. Peer motivational climate in Youth Sport: Measurement Development and Validation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 27, 432–455 (2005).

Wentzel, K. R. Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: implications for understanding motivation at school. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 76–97 (1999).

Ahmadi, A. et al. A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviors recommended in self-determination theory interventions. J. Educ. Psychol. 115, 1158–1176 (2023).

Wang, F. B. H., Wang, Y. C. & Tan, Z. Y. The impact of peer support on adolescents’ physical activity: a study. China Sport Sci. Technol. 54, 18–24 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Teaching Reform Project (Grant No. ZZ223442). This study presents one of the research outcomes of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. designed the study, interpreted the results, and drafted and edited the manuscript. Y.S. and E.F. prepared the materials and participated in data collection and analysis. W.D. critically revised the draft of the manuscript and was responsible for funding acquisition. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Sun, Y., Fan, E. et al. Revision and validation of the “Motivational Climate in Physical Education Scale” (MCPES) in Chinese educational context. Sci Rep 14, 25799 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76803-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76803-1