Abstract

The phase transitions in IrTe2 have been extensively studied but the symmetry at each phase is yet to be settled. Employing second harmonic generation (SHG) measurements over a temperature range of 4 –300 K, we probe the evolution of the symmetry of IrTe2. Our results indicate shifts in two distinct transition temperatures (Ts1 and Ts2 with Ts1 > Ts2) through thermal cycling, providing an explanation for the variations of reported values in literature. The SHG polarimetry measurements identify symmetries in different temperature ranges, confirming the trigonal symmetry above Ts1, the triclinic symmetry between Ts1 and Ts2, and the coexistence of multiple stripe phases below Ts2. The most striking feature is the reemergence of a trigonal phase as reflected by six-fold symmetry below ~ 10 K which is likely responsible for phenomena observed at low temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have drawn significant attention in the field of condensed matter physics, because of their unique structures accompanied with rich physical properties. TMDs are composed of chalcogens (Ch) separated by a transition metal (T), forming Ch-T-Ch slabs1. Such a layered structure is advantageous for dimensionality manipulation and physical property control, which could serve as a complement to graphene in a new class of highly versatile and stackable 2D materials. Due to their wide variety of electronic properties spanning from insulating to conducting to superconducting behavior, TMDs are appealing for applications such as nanoelectronics and nanophotonics2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

Among TMDs, IrTe2 possesses unique structural and physical properties9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. At room temperature (RT), IrTe2 crystalizes in a trigonal symmetry10,11,12,13. Upon cooling, it undergoes multiple phase transitions including two structural transitions with Ts1 ~ 250 –283 K13,23,24,25 and Ts2 ~ 150 –180 K10,13,26 and one superconducting transition with Tc ~ 2.5 K13,14,17,18. The structural phase transitions involve structural distortions in 3D due to the strong interlayer coupling of Te-Te bonds19,20, resulting in the dimerization of Ir-Ir atoms and the formation of stripe phases with multiple periodicities21. For example, the stripe phase below Ts1 is described by the change of a unit cell from 1 × 1 × 1 at T > Ts1 to a 5 × 1 × 5 supercell at T < Ts112. Correspondingly, the surface cell changes from 1 × 1 to 5 × 112. While the formation of the stripe phase below Ts1 is confirmed, there are many unanswered questions associated with all phase transitions. For example, various reports have shown that the structure below Ts1 is either a monoclinic stripe phase11,18,22,23, or a triclinic stripe phase12,13,27,28, or a coexistence of different stripe phases12,15,29,30. Furthermore, while revealing intricate structural information, microscopic-level investigations9,12,29,31 do not show how the structure evolves over a wide temperature range nor does it provide insights into how the symmetry changes in each phase. This gives great difficulty in understanding the underlying physics of IrTe2 at different temperatures. First, what are the dominant phases of IrTe2 at temperatures below Ts1? Second, what causes the variations in the reported transition temperatures (Ts1 from 250 K to 283 K, and Ts2 from 150 K to 180 K)? Third, are there any additional, yet unidentified, phases present at temperatures below Ts2?

In this article, we report second harmonic generation (SHG) measurements on an undoped IrTe2 crystal over a wide temperature range (4 K – 300 K). SHG, in the reflection geometry, is an extremely powerful and sensitive tool for probing the surface symmetry in material systems32,33,34,35,36. As SHG probes the symmetry related information on a larger size scale (~ 5 µm) defined by the optical spot size, we can identify the phase development in the measured temperature range. We subject the sample to multiple thermal cycles and observe under the same illumination spot a systematic shift of the transition temperature Ts1, which decreases with thermal cycles. Interestingly, there is also a shift in Ts2 upon thermal cycling but in an opposite trend to Ts1. Strikingly, we observe the reemergence of a trigonal phase below ~ 10 K and discuss its connection with the prior scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) measurements21,30.

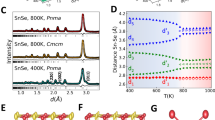

Crystal structure characterization and SHG polarimetry. (a) RT XRD pattern on the flat plane of IrTe2 showing (00l) peaks only as indicated. (b) IrTe2 structure with enclosed black solid lines representing its unit cell and the ab plane at RT. (c) Experimental setup for the SHG polarimetry. (d) SHG polarimetry at RT in the co-polarized (XX) (black open circles) and cross-polarized (XY) (pink open squares) configurations with the solid lines representing the corresponding fits for the trigonal symmetry. The green solid line at \(\:\phi\:\) = 50° indicates the polarization setting under which thermal cycle data is taken.

Experimental methods

High quality single crystals of IrTe2 were grown using the self-flux technique with details described in Ref13. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out at RT using a Rigaku MiniFlex diffractometer. Figure 1a shows the XRD pattern on the flat surface of a single crystal measured at RT, which can be indexed using (00l) with l = integer. The c-axis lattice parameter obtained from XRD is consistent with previous reports11,13 for IrTe2 with the trigonal symmetry (belonging to the P-3m 1 space group). Figure 1b depicts the trigonal symmetry of the RT phase of IrTe2. The ab plane consists of an axis of three-fold rotational symmetry and a mirror plane. The non-centrosymmetric trigonal point group that describes this surface is 3 m.

Figure 1c shows the experimental setup for SHG polarimetry measurements in the normal incidence geometry. A Ti:sapphire femtosecond laser with a center wavelength of 820 nm is used as the incident beam and a dichroic filter, that reflects the fundamental signal (frequency ω) and transmits the SHG signal (frequency 2ω), is used to share the path for incident signal and generated SHG signal. We perform SHG polarimetry by simultaneously rotating the polarizations of incident beam and second harmonic beam (using half wave plates, HWP1 and HWP2, respectively) by an angle \(\:\phi\:\) and resolving the polarization of the SHG signal under both co-polarized (XX) and cross-polarized (XY) configurations utilizing a fixed Glan-Taylor (GT) polarizer as an analyzer. The purpose of these configurations is to mimic sample rotation without rotating the sample. The beam spot is ~ 5 µm in diameter using an infinity-corrected 50× objective lens. The laser power is kept below ~ 6 mW to avoid sample surface damage. Any stray lights are blocked by the filters placed before the detector (photomultiplier tube (PMT)). The axis label (X, Y, Z) in Fig. 1c represents the coordinate system in the lab frame where light propagates towards the detector along the Z-direction and the XY-plane represents the plane of detection. The co-polarized (XX) and cross-polarized (XY) configurations are defined by the fixed GT-polarizer with its transmission axis parallel and perpendicular to the X-axis, respectively.

For thermal cycling, the sample experiences three types of temperature sweeps: initial cooling sweep (~ 2.7 K/min), warming sweep (~ 1.5 K/min), and cooling sweep (~ 2.0 K/min). These warming and cooling rates are lower than the known quenching rates thus avoiding sample quenching15. In the initial cooling sweep, no data can be taken as the temperature cannot be controlled. Prior to SHG measurements, the IrTe2 sample was cleaved at RT to create a fresh surface. The cleaved sample was kept inside the cryostat vacuum chamber (base pressure ~ 1 Torr at RT and ~ 10−4 Torr at T < RT) for all thermal cycling measurements. For each SHG measurement, there is a waiting time of ~ 5 min at each temperature for thermal equilibrium prior to data taking. For comparison, the SHG intensity under XX configuration is monitored at \(\:\phi\:\) = 50° during thermal cycling, corresponding to the maximum of one of the lobes in the six-lobe polarimetry pattern at RT as shown in Fig. 1d.

Electrical resistance measurements were conducted on the same sample, after SHG measurements are completed, via the standard four-probe technique using a physical property measurement system (Dynacool PPMS; Quantum Design). The four probes were made by attaching thin Pt wires to the rectangular-shaped samples using silver epoxy and heat treated for 15 min at ~ 150 °C. The current was passed through the outer two electrodes that cover the cross section to ensure homogeneous current distribution and the corresponding potential was measured across the inner two electrodes allocated in the ab plane. The cooling and warming sweeps for resistance measurements have warming and cooling rates of 0.3 K/min for 1.8 K < T < 10 K and 2 K/min for T > 10 K.

Results and discussion

We conduct SHG polarimetry on the ab plane of IrTe2 at RT and observe six even lobed patterns for both XX and XY configurations as shown in Fig. 1d. Such a pattern is consistent with the trigonal symmetry in the normal incidence geometry37, validating the accuracy of our experimental setup. Next, we investigate the SHG polarimetry patterns in XX and XY configurations at selected temperatures through warming and cooling sweeps. Figure 2 presents SHG patterns through the 9th warming (Warm9) sweep in the top row and 10th cooling sweep (Cool10) in the bottom row. Due to drastic changes upon warming and cooling, we categorize the observed polarimetry patterns into three regions as highlighted by different background colors: pink (region I), green (region II), and blue (region III). Note that the patterns in region I show a clear six-fold symmetry while those in regions II and III do not. To determine the structure symmetry in each region, we conduct global fits to the polarimetry data.

Temperature dependent SHG polarimetry measurements. SHG polarimetry as a function of temperature during the 9th warming (Warm9) and 10th cooling (Cool10) sweeps in XX and XY configurations. Black open circles (pink open squares) represent data for XX (XY) configurations. Each point is an average of 300 independent data points. Solid black (pink) lines are the global fits. Each colored region contains the likewise symmetry patterns. Region I (pink): trigonal (3m) symmetry fitted with Eqs. (1) and (2), region II (green): triclinic (1) symmetry, fitted with Eqs. (3) and (4). region III (blue): undefined mixed phase (not fitted). The intensity in region I is × 0.5 to plot data in the same framework.

From previous studies12,13, it has been established that IrTe2 undergoes a phase transition from trigonal at high temperatures to stripe phases at low temperatures. We thus use two different fitting models, one for the trigonal phase and another for the stripe phase. For the trigonal phase, the non-centrosymmetric point group is 3m. In the normal incidence geometry, the only nonzero element in the second order susceptibility tensor for 3m is \(\:{\chi\:}_{222}\). For convenience, we denote \(\:{\chi\:}_{222}\) as \(\:{\chi\:}_{3 m}\). The corresponding SHG intensities for the 3m symmetry in XX and XY configurations are:

where \(\:\theta\:\) is the initial angle of polarization of light in the experiment. For the stripe phase, since the polarimetry patterns in region II lack mirror symmetry as well as two-fold rotational symmetry, we rule out the monoclinic phase. Therefore, the only relevant non-centrosymmetric point group that matches our observation is triclinic 1. The corresponding SHG intensities for the 1 symmetry in the XX and XY configurations are given by

where \(\:{\chi\:}_{111}\), \(\:{\chi\:}_{122}\), \(\:{\chi\:}_{112}\), \(\:{\chi\:}_{211}\), \(\:{\chi\:}_{222}\) and \(\:{\chi\:}_{212}\) are the nonzero second order susceptibility tensor elements for the 1 symmetry in normal incidence. Polarimetry patterns in region III are not fitted because they lack clear symmetry.

Global fits to the polarimetry data are presented as solid lines in Fig. 2. For region I, data is fitted using Eqs. (1) and (2) for the 3m symmetry. For region II, both intensity and pattern are much lower than that in region I and they are fitted using Eqs. (3) and (4) for the 1 symmetry. While the SHG technique alone cannot distinguish the periodicity of the supercells associated with the stripe phases, assignment can be made by correlating our data with other results. A rigorous surface investigation of IrTe2 utilizing low energy electron diffraction (LEED) and STM measurements12 demonstrates the existence of 5 × 1 stripe phases between Ts1 and Ts2. We thus suggest the 5 × 1 phase in region II. Notably, compared to the pattern symmetry in region II, the symmetry in region III is less defined, suggesting that there are mixed stripe phases as observed in transmission electron microscopy38 all the way down to 7 K through Warm9 and Cool10 (Fig. 2). While LEED shows dominant 8 × 1 stripe below Ts212, our SHG data clearly indicates mixed contributions, reflecting higher sensitivity than that of LEED.

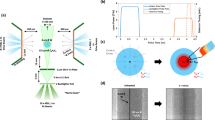

With the identification of symmetries regions I and II, we perform SHG measurements under thermal cycling on our sample to track how Ts1 and Ts2 change. Figure 3a presents the temperature dependence of the SHG intensity measured at \(\:\phi\:\) = 50° as indicated in Fig. 1d. The cooling and warming sweeps include Cool3 (blue circles), Warm7 (red squares), Warm19 (red triangles), and Cool20 (blue triangles). From these sweeps, we notice that Ts1 decreases from the commonly reported value of 280 K at Cool3 to 235 K at Cool20. Interestingly, Ts2 exhibits the opposite trend: it increases from the commonly reported value of 155 K in Cool3 to 190 K in Cool20. The observed thermal cycling effect on both Ts1 and Ts2 is remarkable. To gain insight into the nature of such drastic effect, we further perform electrical resistance measurements on the same IrTe2 sample. Figure 3b displays the temperature dependence of the in-plane resistance through Cool27, Warm28, Cool29, Warm30, Cool31, and Warm32. As indicated by vertical dashed lines, neither Ts1 nor Ts2 changes over thermal cycling. Both Ts1 and Ts2 are nearly the same as that obtained from a fresh sample13. The difference in transition temperatures obtained from SHG and the resistance to thermal cycling strongly suggests that the change in Ts1 and Ts2 are the manifestation of surface response rather than the bulk. While the electrical resistance includes conduction channels from both surface and bulk, the bulk contribution dictates the overall behavior in this case.

Effects of thermal cycling in transition temperatures. (a) SHG intensity as a function of temperature from IrTe2ab plane during different thermal sweeps for \(\:\phi\:\)= 50° in XX configuration (shown by the green solid line in the inset of Fig. 1d). Both transition temperatures shifted significantly as the sample is subject to thermal cycles. Each point on the line is an average of 300 individual data points and the shaded region in each sweep represents the corresponding standard deviation. Inset in the top left corner is the zoomed in view of SHG intensity for temperatures below 20 K where a sharp increase in SHG intensity is observed. The second inset on the bottom left represents the emergence of trigonal symmetry at 7 K. (b) Electrical resistance measurements in bulk IrTe2 for the six consecutive thermal sweeps. No shifts in transition temperatures were observed in resistance measurements due to thermal cycling.

What is more remarkable, and puzzling are the anomalies at temperatures below 10 K in the thermal cycling study. Specifically, a sharp jump is observed in the SHG intensity around 9 K as shown in the top inset of Fig. 3a. Typically, such behavior is associated with some type of phase transition. To further probe the origin of this jump, we performed more polarimetry scans in the low temperature region. While there is no sign in Warm9 and Cool10 at 7 K (Fig. 2), we observe a six-fold symmetry polarimetry pattern at 7 K in Cool12, as shown in the bottom inset of Fig. 3a. This pattern resembles that above Ts1 (region I) but with reduced intensity, a factor of 4 lower compared to that at RT. According to STM studies21,31, trigonal nano-domains within crisscrossing stripe regions can form at low temperatures. This can explain the large intensity difference between the two trigonal SHG signals. We recall that superconductivity of IrTe2 is detected via bulk property measurements including the resistivity drop and diamagnetism below Tc ~ 2.5 K13. Coupling this with the STM investigations, which show that superconductivity can only be seen in the trigonal domains21, our SHG data suggest that considerable number of trigonal domains can occur at low temperatures to warrant a measurable superconducting signal in bulk sensitive quantities such as the magnetic susceptibility and specific heat13. It is justified that, within the laser spot, the trigonal domains make dominant contribution to the SHG signal at 7 K. In view of the polarimetry pattern at Cool12, the formation of trigonal domains is rather a unique low-temperature property than a remnant of the high temperature trigonal phase. This observation highlights the ability of the SHG technique in bridging the knowledge gap between large scale bulk and nanoscale STM measurements.

Based on our SHG data in Fig. 3a, Ts1 and Ts2 approach each other upon thermal cycling, likely associated with the locking of the phases due to the local strain31. According to Ref31, a 0.1% tensile strain applied along the a-axis of IrTe2 results in partial stripe phase in an otherwise pure trigonal phase. Thermal cycling may offer an opposite effect: it gradually releases strain inherent on the surface of IrTe2. In such a scenario, the surface Ts1 decreases with thermal cycling. As for surface Ts2, it marks the onset of the mixed stripe phases. The surface strain relief could promote the formation of mixed stripe phases, leading to the raise of Ts2 upon thermal cycling. Strain also plays an important role for the anomalies observed at temperatures below 10 K. The STM study in Ref21. presents a model which suggests the formation of the trigonal domains as a result of overlapping striped domains orienting at 60° with respect to each other where the domain size has a direct relationship to the local strain. Given the near-degenerate nature of the stripe phases in IrTe231, it is entirely possible that variations in the local strain under the laser spot size upon thermal cycling is enough to cause instabilities and randomize the stripe phase orientations. This can explain why the trigonal phase at 7 K was not consistently observed due to the delicate conditions required. Overall, the trend in the thermal cycling measurement suggests Ts1 and Ts2 at the surface will eventually merge and become a single transition temperature, Ts. From this point of view, the surface hysteresis (Ts1\(\:\ne\:\) Ts2) can be removed, while the bulk remains unchanged under the same condition as seen in the resistance data in Fig. 3b. Our investigation demonstrates that the surface strain relaxation is quite different from that in the bulk due to the broken translational symmetry.

Conclusions

Using SHG measurements, we study the structural phase transitions in IrTe2 in a wide temperature range. The SHG pattern shows different symmetries in different temperatures: (i) at T > Ts1, the SHG pattern can be well described by the 3m symmetry, (ii) at Ts2 < T < Ts1, the SHG pattern shows a reduced symmetry of 1, (iii) at T < Ts2, SHG intensity is weaker and is nearly featureless, and (iv) at T < 10 K, a possible new phase emerges with an associated SHG pattern showing the six-fold symmetry. Our new findings also include the systematic changes of Ts1 and Ts2 with thermal cycling. The decrease of Ts1 and the increase of Ts2 upon thermal cycling may be related to the surface strain relief, as the transition temperatures in bulk remain unchanged through resistance measurements under the same process. Variations in the local strain upon thermal cycling might also explain the lack of reproducibility of the low temperature trigonal phase with the six-fold symmetry.

It should be emphasized that our investigation, combining both SHG and electrical resistance measurements, allows us for the first time to reconcile the discrepancies in terms of structural transitions in IrTe2: (1) the difference in reported Ts1 and Ts2 values are related to the surface structural changes, (2) when Ts1 = Ts2, the pure stripe phase is absent, and (3) it is possible to form trigonal-phase domains at low temperatures. However, the stability of such domains depends on the balance/imbalance of various mixed stripe phases below Ts2.

Data availability

The datasets obtained and/or analyzed in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ovchinnikov, A. S. et al. Unbiased identification of the Griffiths phase in intercalated transition metal dichalcogenides by using Lee-Yang zeros. Phys. Rev. B. 106, L020401 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Engineering graphene and TMDs based Van Der Waals heterostructures for photovoltaic and photoelectrochemical solar energy conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 4981–5037 (2018).

Akinwande, D., Petrone, N. & Hone, J. Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics. Phys. Commun. 5, 5678 (2014).

Munkhbat, B., Küçüköz, B., Baranov, D. G., Antosiewicz, T. J. & Shegai, T. O. Nanostructured transition metal Dichalcogenide Multilayers for Advanced Nanophotonics. Laser Photon Rev. 17, 2200057 (2023).

Gelly, R. J. et al. An inverse-designed Nanophotonic Interface for excitons in Atomically Thin materials. Nano Lett. 23, 8779–8786 (2023).

Chowdhury, T., Sadler, E. C. & Kempa, T. J. Progress and prospects in transition-metal Dichalcogenide Research Beyond 2D. Chem. Rev. 120, 22, 12563–12591 (2020).

Mueller, T. & Malic, E. Exciton physics and device application of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 29 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Valleytronics in transition metal dichalcogenides materials. Nano Res. 12, 2695 (2019).

Rumo, M. et al. Break of symmetry at the surface of IrTe2 upon phase transition measured by x-ray photoelectron diffraction. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 34, 075001 (2022).

Fang, A. F., Xu, G., Dong, T., Zheng, P. & Wang, N. L. Structural phase transition in IrTe2: a combined study of optical spectroscopy and band structure calculations. Sci. Rep. 3, 1153 (2013).

Ko, K. T. et al. Charge-ordering cascade with spin–orbit Mott dimer states in metallic iridium ditelluride. Nat. Commun. 6, 7342 (2015).

Chen, C. et al. Surface phases of the transition-metal dichalcogenide IrTe2. Phys. Rev. B. 95, 094118 (2017).

Cao, G., Xie, W., Phelan, W. A., DiTusa, J. F. & Jin, R. Electrical anisotropy and coexistence of structural transitions and superconductivity in IrTe2. Phys. Rev. B. 95, 035148 (2017).

Yoshida, M., Kudo, K., Nohara, M. & Iwasa, Y. Metastable Superconductivity in two-dimensional IrTe2 crystals. Nano Lett. 18, 3113–3117 (2018).

Rumo, M. et al. Examining the surface phase diagram of IrTe2 with photoemission. Phys. Rev. B. 101, 235120 (2020).

You, J. S. et al. Thermoelectric properties of the stripe-charge ordering phases in IrTe2. Phys. Rev. B. 103, 045102 (2021).

Park, S. et al. Superconductivity emerging from a stripe charge order in IrTe2 nanoflakes. Nat. Commun. 12, 3157 (2021).

Matsumoto, N., Taniguchi, K., Endoh, R., Takano, H. & Nagata, S. Resistance and susceptibility anomalies in IrTe2 and CuIr2Te4. J. Low Temp. Phys. 117, 1129 (1999).

Saleh, G. & Artyukhin, S. First-principles theory of phase transitions in IrTe2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 2127–2132 (2020).

Oh, Y. S., Yang, J. J., Horibe, Y. & Cheong, S. W. Anionic depolymerization transition in IrTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 127209 (2013).

Kim, H. S. et al. Nanoscale Superconducting Honeycomb Charge Order in IrTe2. Nano Lett. 16, 4260 – 4265 (2016).

Ootsuki, D. et al. Electronic structure Reconstruction by Orbital Symmetry breaking in IrTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 093704 (2013).

Pyon, S., Kudo, K. & Nohara, M. Superconductivity Induced by Bond breaking in the triangular lattice of IrTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 81, 053701 (2012).

Ootsuki, D. et al. Orbital degeneracy and Peierls instability in the triangular lattice superconductor Ir1-xPtxTe2. Phys. Rev. B. 86, 014519 (2012).

Taylor, J. E. et al. Electronic phase transition of IrTe2 probed by second Harmonic Generation. Chin. Phys. Lett. 35, 097102 (2018).

Eom, M. J. et al. Dimerization-Induced Fermi-Surface Reconstruction in IrTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 266406 (2014).

Pascut, G. L. et al. Dimerization-Induced Cross-layer Quasi-two-dimensionality in metallic IrTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 086402 (2014).

Cao, H. et al. Origin of the phase transition in IrTe2: structural modulation and local bonding instability. Phys. Rev. B. 88, 115122 (2013).

Li, Q. et al. Bond competition and phase evolution on the IrTe2 surface. Nat. Commun. 5, 5358 (2014).

Hsu, P. et al. Hysteretic melting transition of a soliton lattice in a commensurate charge modulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 266401 (2013).

Nicholson, C. W. et al. Uniaxial strain-induced phase transition in the 2D topological semimetal IrTe2. Commun. Mater. 2, 25 (2021).

Jakobsen, C., Podenas, D. & Pedersen, K. Optical second-harmonic generation from Vicinal Al(100) crystals. Surf. Sci. 321, 1–2 (1994).

Bourguignon, B. et al. On the anisotropy and CO coverage dependence of SHG from pd(111). Surf. Sci. 515, 2–3 (2002).

Cheikh-Rouhou, W. et al. SHG anisotropy in Au/Co/Au/Cu/vicinal Si(111). J. Magn. Mag Mater. 240, 1–3 (2002).

Heinz, T. F., Loy, M. M. T. & Thompson, W. A. Study of Si(111)surfaces by Optical Second-Harmonic Generation: Reconstruction and Surface Phase Transformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 1 (2018).

Chavez, B. L. et al. Hidden anomalies in topological t–PtBi2–x probed by second harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. B. 108, 224104 (2023).

Zu, R. et al. Analytical and numerical modeling of optical second harmonic generation in anisotropic crystals using ♯SHAARP package. Npj Comput. Mater. 8, 246 (2022).

Wang, Z., Cao, G., Zhang, J., Zhu, Y. & Jin, R. Visualizing Three-dimensional Phase Transitions in IrTe2 via in-situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (unpublished).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Jie Xing for his assistance in the XRD measurements. This work was partially supported by Grant No. 1652720 funded by the National Science Foundation (YW) and by Grant No. DE-SC0024501 (RJ) funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. H. grew the single crystals of IrTe2. G. K. carried out the XRD measurement, designed and executed the second harmonic generation measurements, and analyzed the data. B. L. C. conducted electrical resistance measurements and contributed to the regular discussion of this project. G. K., R. J. and Y. W. wrote the manuscript. R. J. and Y. W. supervised the project. All authors have given approval to the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kharal, G., Chavez, B.L., Huang, S. et al. Evolution of the surface phase transitions in IrTe2. Sci Rep 14, 24857 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76853-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76853-5