Abstract

Out-of-hospital mortality in coronary artery disease (CAD) is particularly high and established adverse event prediction tools are yet to be available. Our study aimed to investigate whether precision phenotyping can be performed using routine laboratory parameters for the prediction of out-of-hospital survival in a CAD population treated by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). All patients treated by PCI and discharged alive in a tertiary center between January 2016 – December 2022 that have been included prospectively in the local registry were analyzed. 115 parameters from the PCI registry and 266 parameters derived from routine laboratory testing were used. An extreme gradient-boosted decision tree machine learning (ML) algorithm was trained and used to predict all-cause and cardiovascular-cause survival. A total of 4027 patients with 4981 PCI hospitalizations were randomly included in the 70% training dataset and 1729 patients with 2160 PCI hospitalizations were randomly included in the 30% validation dataset. All-cause and cardiovascular cause mortality was 17.5% and 12.2%. The integrated area under the receiver operator characteristic curve for prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular cause mortality by the ML on the validation dataset was 0.844 and 0.837, respectively (all p < 0.001). Parameters reflecting renal function (first and maximum serum creatinine), hematologic function (mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, platelet distribution width), and inflammatory status (lymphocyte per monocyte ratio) were among the most important predictors. Accurate out-of-hospital survival prediction in CAD can be achieved using routine laboratory parameters. ML outperformed clinical risk scores in predicting out-of-hospital mortality in a prospective all-comers PCI population and has the potential to precisely phenotype patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extensive research has been dedicated to the prediction of adverse events in the coronary artery disease (CAD) population given the high associated mortality rates. CAD has a median general incidence of 293 per 100 000 people and is the most important cause of premature mortality worldwide1. A recent study reported a 15% all-cause mortality rate at 3 years in CAD population2. Numerous clinical, angiographic, and combined risk scores were developed to estimate survival, such as Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score, Age, Creatinine, and Ejection fraction (ACEF) score, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) score and Synergy Between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) score3,4,5,6. However, in many available risk scores the overall prediction performance is mainly driven by high accuracy in predicting in-hospital death, since the presence of very high-risk clinical features almost invariably leads to in-hospital death (e.g., cardiogenic shock, acute pulmonary edema, resuscitated cardiac arrest, mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction, severe anemia or acute kidney injury), while out-of-hospital death prediction is frequently under-investigated. There is a research gap regarding out-of-hospital death prediction and may be more difficult to predict also due to factors beyond the initial hospitalization (e.g., compliance to prescribed treatment). Moreover, long-term survival in CAD is less determined by the complexity of coronary anatomy7. Thus, more research is needed to find robust predictors of impaired survival in the CAD population, especially after hospital discharge.

Phenotype, initially defined as “the observable traits of an organism”, nowadays includes clinical and paraclinical characteristics of a patient (e.g., diagnostic imaging, laboratory parameters, electrocardiographic changes)8. According to the patient’s phenotypic abnormalities, both diagnostic and prognostic assessments can be made8. Precision phenotyping is a concept that implies a comprehensive analysis of a wide panel of clinical parameters usually using artificial intelligence (AI) techniques which can quantify even slight changes in a patient’s phenotype and offer a precise prognostic estimate. Precision phenotyping has been previously proposed using clinical, ultrasound, computed tomography, or big “-omic” data9,10,11. Whether a precise survival estimate can be given using a spectrum of laboratory parameters routinely measured in clinical practice is yet to be proven.

The aim of the present study was (1) to train a machine learning (ML) model to predict out-of-hospital all-cause and cardiovascular cause mortality using a wide panel of laboratory parameters, (2) to identify predictors of out-of-hospital adverse events using the SHAP framework, and (3) to compare the predictive performance of ML model with clinical risk scores relevant for CAD population, in an all-comers patient population treated by PCI in a Romanian tertiary cardiovascular center.

Materials and methods

Population selection protocol

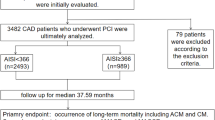

The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1. All patients treated by PCI in the Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases and Transplantation of Târgu Mureş have been prospectively included at discharge in the local PCI Registry of the Institute since January 2016. For the current analysis, all patients treated between January 2016 – December 2022 were included, in order to have a minimum of 6 months of follow-up. Subjects were analyzed by PCI hospitalization (hospitalization in which PCI was performed). Exclusion criteria consisted of (1) age less than 18 years old, (2) presence of in-hospital death, or (2) lack of available survival data (e.g., foreign patients). The Registry is accessible online at the website http://pci.cardio.ro/ and is based on the criteria of Cardiology Audit and Registration Data Standards (CARDS) developed by the Department of Health and Children, European Society of Cardiology, Irish Cardiac Society, and the European Commission12. Briefly, the CARDS recommendations address data regarding demographics, relevant medical history, and comorbid conditions, clinical status at hospital admission, PCI indication, affected and treated coronary artery segments, usage of invasive diagnostic or therapeutic devices, procedural complications, medical treatment during hospitalization and at discharge and in-hospital evolution. All the information available regarding all the variables proposed in that document was collected for each included patient, at every PCI. A number of 115 parameters were available from the PCI registry. Moreover, to complete and update the original CARDS recommendations regarding PCI procedures, an additional 266 laboratory parameters were also collected (Supplemental Table 1). Noteworthy, all laboratory data during the PCI hospitalization was acquired from the electronic health record (EHR). Since the timing and number of determinations of laboratory parameters differ between patients and hospitalizations, each laboratory parameter was considered separately first value in hospital, last value before discharge, average value during hospitalization, absolute maximum and minimum value, and number of each separate determination of that certain laboratory parameter (e.g., first creatinine, last creatinine, average creatinine, maximum and minimum creatinine, number of creatinine determinations, Supplemental Table 1). A total of 381 parameters were used for the final analysis. Furthermore, clinical, and angiographic risk scores such as ACEF, GRACE, and SYNTAX score were also calculated for comparison with the ML model’s survival prediction performance.

All patients or their legal representatives provided a signed informed consent regarding the PCI procedure and their participation in the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of our institution (decision number 8646 / 22 December 2015). The protocol was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects established by the Declaration of Helsinki, protecting the confidentiality of personal information of the patients.

Follow-up and clinical outcomes

The clinical endpoint of this study was the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Out-of-hospital mortality was defined as death that occurred after discharge, but not occurring during the initial hospital admission when the PCI procedure was performed. The Romanian National Health Insurance System database supplied mortality rates as of July 2023 for all the patients. For patients who had died during follow-up, the Regional Statistics Office of the Romanian National Institute of Statistics supplied the exact date and cause of death according to the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). If the cause of death belonged to diseases of the circulatory system, then death was considered to be of cardiovascular cause.

Machine learning

All patients had a minimum of 6 months survival status available and up to 6 years of follow-up. Patients were dichotomized every 6 months into alive/deceased groups and censored events were removed. Afterward, for each timeframe, the dataset was randomly divided into 70% training and 30% validation datasets. To prevent data leaks since a patient could have multiple hospitalizations, each patient was assigned to either a training or validation set. On the 70% training dataset, a 5-fold cross-validation was performed and to prevent data leak between folds, each patient was only assigned to one-fold. An extreme gradient boosted decision tree (XGBoost) algorithm13 was evaluated as a binary classifier for predicting both all-cause- and cardiovascular-cause mortality occurred out of hospital, for each timeframe. XGBoost algorithm was implemented in Python version 3.9.13. Hyperparameter optimization was performed by using Bayesian search on 6 years survival status, being the least imbalanced dataset, and those best training parameters were used for all timeframes. The range specified for hyperparameter tuning was learning rate between 0.01 and 1.0, maximum depth between 3 and 12, L1 and L2 regularization between e− 9 and 102, number of trees between 50 and 5000, subsampling and column subsampling between 0.1 and 1.0. The accessibility of underlying supporting scripts is detailed in the data availability section. In order to explain the ML decision process, the open-source Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) framework was used14. Most important features were obtained as follows: (1) SHAP values were obtained for each of the database values at each timeframe, for both all-cause and cardiovascular cause events; (2) at each timeframe, absolute SHAP values were added, and parameters’ importance was considered by the highest sum of absolute SHAP value (e.g., the parameter with the highest absolute SHAP values sum at 5-years cardiovascular survival was the most important); (3) overall most important predictors were obtained by ascending classification of averaged positions at all timeframes for all-cause and cardiovascular cause survival, separately (see supporting code). Illustration of time-dependent SHAP values for a certain parameter on a specified survival (e.g., time-dependent SHAP values for age impact on all-cause survival) was performed as follows: (1) SHAP values were obtained for every value of that parameter at each timeframe on the specified survival; (2) for the specified parameter, ten percentile intervals were obtained according to the minimum and maximum value; (3) SHAP values were averaged for each percentile at each timeframe; (4) 3D mesh plot was illustrated using the ten percentiles of that parameter, all investigated timeframes and averaged SHAP values for that percentile; (5) in order to correlate averaged SHAP values with actual observed survival, the now 4D mesh plot was coloured by averaged survival for each parameter percentile at each timeframe (see supporting code). While XGBoost was the default ML algorithm used, other consecrated algorithms were trained for comparison, including CatBoost, Random Forest, and TabNet. Furthermore, we investigated if predictive performance could be improved using oversampling techniques, such as the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), or dimensionality reduction techniques, such as principal component analysis (PCA). For each laboratory parameters pair (e.g., creatinine at presentation, at discharge, maximum, minimum and number of measurements), PCA was performed with one, two and three components.

Performance metrics

Performance on survival prediction was measured by (1) the time-integrated area under the curve of receiver-operator characteristic (AUC-ROC): \(\:integrated\:AUC\text{-}ROC=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}AUC\text{-}ROC\:\left(t\right)dt\), where AUC-ROC (t) is the area under the ROC curve at a specific time t, t0 is the starting time for the analysis, and tmax is the maximum time point of interest, (2) the time-integrated area under the curve of precision-recall (AUC-PR): \(\:integrated\:AUC\text{-}PR=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}AUC\text{-}PR\:\left(t\right)dt\), where AUC-PR (t) is the area under the precision-recall curve at a specific time t, t0 is the starting time for the analysis, and tmax is the maximum time point of interest, (3) the time-integrated Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC): \(\:integrated\:MCC=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}MCC\:\left(t\right)dt\), where MCC (t) is the Matthews correlation coefficient at a specific time t, t0 is the starting time for the analysis, and tmax is the maximum time point of interest; MCC is calculated as \(\:MCC=\frac{TPXTN-FPXFN}{\sqrt{(TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)(TN+FN)}}\) , where TP, TN, FP and FN are true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, (4) the time-integrated F1 score: \(\:integrated\:F1=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}F1\:\left(t\right)dt\), where F1 (t) is the F1 score at a specific time t, t0 is the starting time for the analysis, and tmax is the maximum time point of interest; F1 score is calculated as \(\:F1=\frac{2\times\:Precision\times\:Recall}{Precision+Recall}\), and (5) the time-integrated Brier score: \(\:integrated\:Brier\:score=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}Brier\:score\:\left(t\right)dt\), where Brier score (t) is the Brier score at a specific time t, t0 is the starting time for the analysis, and tmax is the maximum time point of interest. While for AUC-ROC the baseline is constant at 0.5, in the case of AUC-PR, the baseline is determined by positive cases per total cases ratio15. Thus, a baseline-corrected AUC-PR was calculated by subtracting the baseline value from the AUC-PR value: \(\:integrated\:AUC\text{-}PR\:baseline\text{-}corrected=\frac{1}{{t}_{max}-{t}_{0}}{\int\:}_{{t}_{0}}^{t\:max}(AUC\text{-}PR\:\left(t\right)-baseline\:\left(t\right))dt\), where baseline (t) is the ratio between positives and total cases at a specific time. MCC and F1 score calculation requires dichotomization from probability for ML model and score value for clinical risk scores into predicted deceased or alive, which was performed using Youden’s method for cut-off calculation.

Statistical analysis

A significance level α of 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were considered. Continuous variables were evaluated for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables with parametric distributions were reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using non-paired Student’s t-test, while continuous variables with non-parametric distributions and discrete variables were reported as median (interquartile range) and compared using Mann Whitney test. Categorical variables were reported as absolute and relative frequencies and compared using Fisher’s exact test for clinical parameters with frequencies less than 5 and the Chi2 test otherwise. For baseline clinical characteristics, univariate Cox proportional hazard was used to predict the association in the form of hazard ratio (HR) between observed survival and an independent categorical variable. All continuous variables were dichotomized related to the median to facilitate comparability of HR and CI between variables. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.1 and R Studio version 1.4.17.

Results

Included population

A total of 7186 PCI hospitalizations for 5797 patients were included in the present study, with a total of 611,309 laboratory values. Of those patients, 4062 (70.07%) were male sex, the median age was 65.0 (57.2–71.8) years, and the median BMI was 28.3 (25.9–31.8) kg/m2. Complete clinical characteristics of the studied patients are reported in Table 1 and Supplemental Table (1) Complete clinical characteristics of the studied PCI hospitalizations are reported in Table 2 and Supplemental Table (2) A total of 1017 (17.5%) patients died of all causes during a median follow-up time of 1454 (687–2072) days. When censoring events of non-cardiovascular cause, a total of 710 (12.2%) patients died of cardiovascular causes during a median follow-up time of 1544 (748– 2155) days. Cumulative per-patient mortality incidence is illustrated in Fig. 2A and cumulative per-PCI mortality incidence is illustrated in Fig. 2B. A total of 115 clinical parameters were available from the PCI registry. A median of 114 (110–115) parameters were available for each patient as some parameters were missing or not applicable (e.g., time from symptom onset to PCI, which is measured in acute but not in chronic coronary syndrome). A total of 611,309 laboratory values were analyzed for all 7186 hospitalizations. Per hospitalization, a median of 78 (65–116) laboratory values were available. For each laboratory parameter, the first and last in-hospital value, maximum and minimum value during hospitalization, averaged value during hospitalization, and number of determinations for that parameter during hospitalization were calculated, therefore 266 additional parameters were analyzed.

Machine learning model analysis

A number of 4027 patients with 4981 PCI hospitalizations were randomly included in the 70% training dataset and 1729 patients with 2160 PCI hospitalizations were randomly included in the 30% validation dataset. XGBoost models accurately predicted out-of-hospital survival at all timeframes on all time-dependent performance metrics (Fig. 3). While AUC-ROC was consistently high (Fig. 3A and C), AUC-PR gradually increased as the deceased-to-alive ratio became less imbalanced (Fig. 3B and D). Minor differences were between testing dataset predictions and validations dataset predictions, revealing that overfitting did not occur (Fig. 3). Tuned hyperparameters found by Bayesian search included a total of 5000 aggregated decision trees, with a maximum tree depth of 3 levels, a learning rate of 0.01, L1 and L2 regularization of e− 9 (see supporting code). Most important survival predictors were obtained by classifying the averaged importance position at all timeframes. For all-cause mortality, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), age, hospitalization cost, heart rate at presentation, renal function reflected by maximum creatinine during hospitalization, standard deviation of red cell distribution width and last determined before discharge lymphocyte per monocyte ratio were among the most important parameters. For cardiovascular cause mortality, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), age, systolic and diastolic blood pressure at presentation, heart rate at presentation, hospitalization cost, renal function reflected by maximum creatinine during hospitalization, the standard deviation of red cell distribution width and last determined before discharge lymphocyte per monocyte ratio was among the most important parameters. Furthermore, the most important factors for the occurrence of adverse events and most important factors against the occurrence of adverse events of any cause and cardiovascular cause are reported in Supplemental Fig. 1. Time-dependent SHAP values are reported in Fig. 4 and reveal how the predictor’s values (e.g., advanced age or reduced LVEF) predispose to adverse events. Patient individualized survival prediction can be illustrated using XGBoost probability output at each timeframe with event occurrence estimated at the point where probability is less than the cut-off for that specific timeframe (Fig. 5).

Comparison between machine learning and clinical scores

To illustrate the predictive performance of XGBoost models, some important clinical risk scores, such as ACEF, GRACE, or SYNTAX scores, were also calculated and compared with XGBoost models. XGBoost consistently and significantly outperformed clinical risk scores on all timeframes (Fig. 3) and all performance metrics (Table 3). Among clinical scores, the ACEF score had the highest performance metrics, while the SYNTAX score had the lowest performance metrics. The integrated AUC-ROC for prediction of all-cause mortality by the XGBoost model versus ACEF score was 0.844 and 0.735, respectively (Table 3). The integrated AUC-ROC for prediction of cardiovascular cause mortality by the XGBoost model versus ACEF score was 0.837 and 0.761, respectively (Table 3). A more striking increase in prediction performance is reflected by the integrated AUC-PR and integrated baseline-corrected AUC-PR. The integrated AUC-PR for prediction of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality by the XGBoost model was 0.647 and 0.589, respectively, while for ACEF score was 0.380 and 0.410, respectively (Table 3). The integrated baseline corrected AUC-PR for prediction of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality by the XGBoost model was 0.407 and 0.428, respectively, while for ACEF score was 0.199 and 0.190, respectively (Table 3). Additional details regarding performance metrics are reported in Supplemental Table 3. Other metrics, such as integrated MCC, F1, and Brier score were also in favor of XGBoost models.

Comparison between different AI models in predicting out-of-hospital death

To comparatively assess prediction performance of various consecrated AI models, we additionally trained CatBoost, Random Forest and TabNet models, besides XGBoost. Interestingly, CatBoost had the closest performance to XGBoost (AUC-ROC for all-cause mortality of 0.786 versus 0.837, p = 0.04), while Random Forest and TabNet had worse prediction performance than XGBoost (Table 4). Moreover, neither oversampling technique, such as SMOTE, or decreasing the number of variables using PCA (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussions

The main findings of our study are: (1) In a prospective all-comers PCI registry, both all-cause and cardiovascular cause out-of-hospital mortality is high, with 6-years mortality of up to 42%; (2) ML models can accurately predict long-term out-of-hospital survival in a CAD population treated by PCI using routine laboratory parameters; (3) Predictive performance of ML models was better than relevant clinical scores, such as GRACE, ACEF or SYNTAX score on all performance metrics, including integrated AUC-ROC, AUC-PR, MCC, F1 and Brier score; (3) Important factors for survival prediction includes age, LVEF, blood pressure and heart rate on presentation. However, most important factors were those derived from laboratory parameter analysis; (4) Time-dependent SHAP values reveal how the values of a parameter impact predictions for each timeframe.

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death16, although precise long-term follow-up from the moment of CAD diagnosis, especially out-of-hospital, is scarce. In our study 5-year and 6-year all-cause, out-of-hospital mortality was 21.7% and 33.2%, respectively, relatively lower than the 5-year all-cause mortality of 37.3% from the SYNTAX trial although it included only three-vessel CAD disease17. In patients with established CAD, clinical risk prediction tools for secondary prevention are useful, considering the high mortality associated with CAD. For this purpose, certain clinical scores such as ACEF, SYNTAX, and GRACE scores were developed3,4,6. Refinements of clinical scores were attempted to improve predictive performance, particularly for the original SYNTAX score, from which several SYNTAX-derived scores were reported18. In our analysis, ML models outperformed clinical scores on all timeframes and all statistical metrics (Table 3). Accordingly, the use of machine learning instead of continuously refined traditional risk scores seems to be more efficient in long-term mortality risk prediction in CAD patients, especially if clinical data can reliantly be obtained from EHR. In the present study, over 600,000 laboratory values were automatically obtained from the EHR, making future integration in clinical practice possible.

SHAP is a recognized methodology in explainable AI, it is based on cooperative game theory, particularly the Shapley values, which assign a fair contribution to each feature in a prediction14. SHAP assumes the model output is the sum of contributions from all parameters and calculates how much each feature’s presence, compared to its absence, contributes to that prediction14. In our analysis, LVEF, age, blood pressure, and heart rate were among the most important predictors, which are also partially included in clinical scores such as ACEF and GRACE scores. High hospitalization cost and increased contrast volume were also predictors of events, reflecting the need for advanced therapies and long or complex PCI procedures, respectively. Interestingly, numerous important clinical features were obtained from laboratory values, reflecting renal function (first and maximum serum creatinine and urea levels), hematologic function (red cell distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, platelet distribution width), inflammatory status (lymphocyte per monocyte ratio, maximum neutrophil count) and glycemic status (Fig. 6). Most of the mentioned parameters were previously reported as predictors of adverse events. The association between lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and impaired prognosis in the CAD population has been documented in a recent meta-analysis19. Other studies showed that red cell distribution width is an inexpensive prognostic marker in both myocardial infarction and heart failure20,21. This illustrates that precision phenotyping can be achieved using laboratory parameters. Moreover, while the clinician works with dichotomized outcomes from continuous variables (e.g., patient has heart failure with reduced ejection fraction if LVEF ≤ 40%) leading to an information loss22, ML models are particularly powerful in analyzing continuous data without the need for fitting into categories – for this reason, the most important parameters were laboratory values instead of disease labels. Interestingly, the severity of coronary lesions was not particularly important for long-term prognosis. Similarly, SYNTAX score performance decreased over time, revealing that coronary anatomy is less important in the long term.

The emergence of AI brought numerous tools for prediction making, which can be simplistically categorized as supervised learning using machine learning techniques (e.g., support vector machines or gradient-boosted decision trees) or unsupervised learning using deep learning techniques (e.g., neural networks). Depending on the underlying task, certain algorithms could be more suitable. In our study, gradient-boosting algorithms (XGBoost and CatBoost) and random forest outperformed deep learning (Table 4), in line with other previous studies that showed gradient-boosted tree ensembles outperforming deep learning models on supervised learning tasks by an important margin23. Indeed, for tabular data, deep learning seldom outperforms machine learning24. Interestingly, oversampling techniques, such as SMOTE, or dimensionality reduction techniques, such as PCA, did not manage to improve prediction performance (Supplemental Table 4).

Regarding survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazards models have successfully been used for decades25. However, both techniques consider a linear relationship between the risk factor and the log hazard function26. This constant effect of the risk factor during the follow-up assumed by the Kaplan–Meier and Cox models could be an oversimplification26. Recently, ML methods were proposed to analyze survival data27. More specifically, standard ML techniques use binary classification to predict the outcome at a certain timeframe. This requires dichotomization with removal of censored data, does not consider hazards a function of time, but has a high interpretability of the model. On the other hand, modified ML techniques for survival data are adjusted to consider hazards as a function of time, to handle censored and time-to-event data, but have lower interpretability27. Moreover, numerous performance metrics to evaluate survival prediction models are time-dependent and require the removal of censored events (e.g., Brier score or time-dependent area under receiver operator characteristic)28. Indeed, there are a variety of ML and deep learning techniques to analyze survival data, and the best technique to perform survival analysis is yet to be determined. Nevertheless, the method illustrated in this study, which used binary dichotomization at each timeframe, revealed that accurate individual survival curves can be plotted (Fig. 5). It had potential important application, since survival curves can be plotted within different clinical scenarios – for instance if survival is estimated to be longer after PCI treatment than after surgical revascularization in a CAD patient, then the former could be used.

A reproducibility crisis is increasingly recognized in the area of AI, driven mainly by data leakage and lack of transparency by unpublished code29,30. Indeed, data leakage – the ability of the AI model to see the outcome of the training dataset – is an important problem that may remain undetected31. In our previous study, an unexpected data leak was observed – the ML model was making an unrealistic nearly perfect in-hospital mortality prediction by looking at treatment at discharge, recognizing that if a patient did not have medical treatment at hospital discharge it was because the patient was deceased2. In the current study, we consider data leak to be highly improbable, since (1) only in-hospital data was analyzed, (2) only out-of-hospital death was considered, and (3) survival data was acquired from a different institution. Moreover, survival data was not merged with clinical data during the analysis. Regarding underlying code, a report revealed that 6% of AI papers are accompanied by complete code, while half of the AI papers contained “pseudocode”, a brief description of the algorithm32. In line with current recommendations, the underlying algorithm code for the current study is publicly disclosed.

Study limitations and future research directions

The main limitation of our study is the lack of external validation. In addition, the study population is typical for Eastern Europe, thus extrapolating to other populations could be limited. Although not a limitation per se, we are the first to illustrate a time-dependent SHAP plot and certain time-integrated statistical indicators (e.g., integrated AUC-PR and baseline corrected AUC-PR) which warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

Machine learning can accurately predict out-of-hospital all-cause and cardiovascular cause death using routinely performed laboratory parameters and outperforms classic clinical parameter-based risk scores in a prospectively followed CAD population treated by PCI. Individual survival curves can be estimated for each patient which can lead to an improved out-of-hospital event prediction and precise clinical phenotyping. Further research is needed to evaluate the potential of individual survival curves in estimating event risk reduction, particularly by adjusting various factors such as treatment options.

Data availability

Due to national and EU regulations, particularly the General Data Protection Regulation, the data used in this study cannot be made publicly available and shared with the wider research community. The data can be shared by the corresponding author for use in secure environments upon request. However, all Python scripts underlying this study are publicly available at https://github.com/paul-md/Survival-ML.

References

Timmis, A. et al. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur. Heart J. 43, 716–799 (2022).

Călburean, P. A. et al. Prediction of 3-year all-cause and cardiovascular cause mortality in a prospective percutaneous coronary intervention registry: machine learning model outperforms conventional clinical risk scores. Atherosclerosis. 350, 33–40 (2022).

Tang, E. W., Wong, C. K. & Herbison, P. Global Registry of Acute coronary events (GRACE) hospital discharge risk score accurately predicts long-term mortality post acute coronary syndrome. Am. Heart J. 153, 29–35 (2007).

Chichareon, P. et al. Predictive ability of ACEF and ACEF II score in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the GLOBAL LEADERS study. Int. J. Cardiol. 286, 43–50 (2019).

Mok, Y. et al. International Validation of the Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary Prevention in Post-MI patients: a collaborative analysis of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium and the Risk Validation Scientific Committee. J. Am. Heart Association. 7, e008426 (2018).

Sianos, G. et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/article/the-syntax-score-an-angiographic-tool-grading-the-complexity-of-coronary-artery-disease

Thuijs, D. J. F. M. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease: 10-year follow-up of the multicentre randomised controlled SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 394, 1325–1334 (2019).

Robinson, P. N. Deep phenotyping for precision medicine. Hum. Mutat. 33, 777–780 (2012).

Precision Phenotyping in Heart Failure and Pattern Clustering of Ultrasound Data for the Assessment of Diastolic Dysfunction. https://www.jacc.org/doi/epdf/10.1016/j.jcmghttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.10.012

Oikonomou, E. K., Siddique, M. & Antoniades, C. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: a radiomic guide to precision phenotyping of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular. Res. 116, 2040–2054 (2020).

Delude, C. M. Deep phenotyping: the details of disease. Nature. 527, S14–S15 (2015).

Flynn, M. R. et al. The Cardiology Audit and Registration Data standards (CARDS), European data standards for clinical cardiology practice. Eur. Heart J. 26, 308–313 (2005).

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. & XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S. I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv:1705.07874 [cs, stat] (2017).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating Binary classifiers on Imbalanced datasets. PLOS ONE. 10, e0118432 (2015).

Nowbar, A. N., Howard, J. P., Finegold, J. A., Asaria, P. & Francis, D. P. Global geographic analysis of mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, age and income: Statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. International Journal of Cardiology 174, 293–298 (2014). (2014).

Mohr, F. W. et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 381, 629–638 (2013).

Yadav, M. et al. Prediction of coronary risk by SYNTAX and derived scores. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 1219–1230 (2013).

Quan, X. Q., Wang, R. C., Zhang, Q., Zhang, C. T. & Sun, L. The predictive value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in the prognosis of acute coronary syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 338 (2020).

Al-Najjar, Y., Goode, K. M., Zhang, J., Cleland, J. G. F. & Clark, A. L. Red cell distribution width: an inexpensive and powerful prognostic marker in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 11, 1155–1162 (2009).

Dabbah, S., Hammerman, H., Markiewicz, W. & Aronson, D. Relation between red cell distribution width and clinical outcomes after Acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 105, 312–317 (2010).

Fedorov, V., Mannino, F. & Zhang, R. Consequences of dichotomization. Pharm. Stat. 8, 50–61 (2009).

Borisov, V. et al. Deep neural networks and Tabular Data: a Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35, 7499–7519 (2024).

Shwartz-Ziv, R. & Armon, A. Tabular Data: Deep Learning is Not All You Need. Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.03253

Cox, D. R. Regression models and life-tables. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 34, 187–202 (1972).

Harrell, F. E. Regression Modeling Strategies: with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis vol. 608 (Springer, 2001).

Cygu, S., Seow, H., Dushoff, J. & Bolker, B. M. Comparing machine learning approaches to incorporate time-varying covariates in predicting cancer survival time. Sci. Rep. 13, 1370 (2023).

Park, S. Y., Park, J. E., Kim, H. & Park, S. H. Review of statistical methods for evaluating the performance of survival or other Time-to-event Prediction models (from Conventional to Deep Learning approaches). Korean J. Radiol. 22, 1697–1707 (2021).

Hutson, M. Artificial intelligence faces reproducibility crisis. Science. 359, 725–726 (2018).

Gibney, E. Could machine learning fuel a reproducibility crisis in science? Nature. 608, 250–251 (2022).

Kapoor, S. & Narayanan, A. Leakage and the Reproducibility Crisis in ML-based Science. Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.07048

Gundersen, O. E. & Kjensmo, S. State of the art: Reproducibility in artificial intelligence. in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence vol. 32 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the resident colleagues who continuously introduced the data regarding PCIs performed in the Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases and Transplantation since 2016. We also would like to thank Mr. Ioan Matei for his help in achieving long-term mortality data.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.-A.C. and L.H. were involved in the study design. P.-A.C. and L.H. performed the literature search. L.H. supervised and coordinated the data collection in the registry. P.-A.C. and M.H. were involved in the development of machine learning models and explainable artificial intelligence. All authors were involved in data collection. T.O. was responsible for the development and maintenance of the online platform. P.-A.C. and L.H. analyzed the data. P.-A.C. and L.H. were involved in the writing of the initial draft. All authors were involved in the writing of the final draft and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Călburean, PA., Harpa, M., Scurtu, AC. et al. Precision phenotyping from routine laboratory parameters for out of hospital survival prediction in an all comers prospective PCI registry. Sci Rep 14, 24837 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76936-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76936-3