Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction under the influence of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment. Participants were recruited from eight universities located in six Chinese cities, naming Chongqing, Maoming, Nanjing, Suzhou, Shijiazhuang, and Zhengzhou. The sample consisted of 575 participants enrolled in Chinese universities, with 309 (53.7%) being female students. The mediation model was tested under the structural equation modeling framework using Mplus. Results showed that (1) perceived stress had a direct and negative impact on life satisfaction, and it also had indirect effects through the two mediators; (2) perceived stress positively predicted mobile phone addiction, which, in turn, negatively impacted life satisfaction; (3) perceived stress negatively predicted sport commitment, which, in turn, positively impacted life satisfaction. By emphasizing the mediating roles of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment, our findings highlight the importance of addressing these factors in interventions aimed at encouraging college students’ well-being. Implications for intervention design to promoter health among university students should take into account the mediating roles of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The usage of mobile phones has become ubiquitous, integrating into modern life and enriching various aspects of individuals’ daily experiences. Mobile phones serve multiple purposes, such as enhancing social communication1, providing entertainment2, searching for information3, and offering access to social media4. As of 2023, the number of mobile Internet users in China reached 1.076 billion people, emphasizing the extensive integration of mobile technology into daily life and its broad societal impact5. Although mobile phones undoubtedly offer numerous benefits that significantly improve people’s lives, it is essential to examine the underlying mechanisms of mobile phone usage. For instance, the behavioral mechanism in which mobile phone usage transitions from serving as a social facilitator to becoming a source of distraction and social disconnection manifests when excessive use disrupts face-to-face communication and adversely affects daily life activities6. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use suggests that problematic cognitive patterns are connected to behaviors that either intensify or perpetuate maladaptive responses7, thereby highlighting the cognitive mechanisms driving mobile phone usage. Additionally, excessive mobile phone use may be viewed as an extension of Internet addiction due to the overlap in symptoms that encompass psychological dimensions and reflect a type of behavioral and technological dependence2. Therefore, excessive use of mobile phones poses a potential threat to individuals’ health and well-being through behavioral and cognitive mechanisms, highlighting the necessity for a theoretical investigation into this phenomenon.

Several studies have indicated that excessive mobile phone usage may lead to addiction, which is associated with various psychological and behavioral problems8,9. Mobile phone addiction is a specific form of technology addiction characterized by repetitive and excessive use, leading to detrimental health behaviors10,11. This addiction may arise from reinforcement mechanisms associated with the Internet and emerging mobile phones, influenced by operant conditioning, whereby positive reinforcement form initial interactions facilitates increased engagement7. Additionally, mobile phone usage patterns can be categorized into two types: possible mobile phone addiction and non-addiction12. This categorization assists in identifying individuals with varying levels of mobile phone related issues, from occasional to frequent problems, versus those with controlled usage patterns12. This distinction is crucial for developing targeted interventions and support strategies. Studies consistently demonstrate that mobile phone addiction is associated with negative health outcomes, impacting various aspects of well-being, including quality of life13. Furthermore, mobile phone addiction has been positively associated with mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression14,15. While acknowledging the potential risks associated with mobile phone addiction, it is essential to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework to understand how mobile phone usage affects well-being.

Subjective well-being has become a substantial focus in research on overall health and well-being. The association between subjective well-being and problematic mobile phone usage has been explored16. Subjective well-being can be conceptualized as the extent to which an individual perceptually evaluates the overall quality of their life17. According to the subjective well-being model18, it comprises three components: pleasant affect, unpleasant affects and life satisfaction. Unpleasant affect, a negative aspect of subjective well-being, can be understood as ill-being, including experiences such as stress, depression and anxiety18,19. In addition to these components of ill-being, stress is a well-known negative indicator of mental health. This is not only because individuals frequently experience negative stressful events but also because stress can lead to depression and anxiety20,21,22,23.

Perceived stress is recognized as the extent to which events in an individual’s life are evaluated as being stressful24. The detrimental impact of perceived stress on individuals’ overall health is well-documented25. Furthermore, a positive correlation between perceived stress and mobile phone addiction has been identified26. This empirical finding can be understood through the framework of stress and coping theory27, which defines coping as the strategies used to avert or mitigate threats and losses, or to alleviate related distress28. Specifically, emotion-focused coping strives to reduce distress from stressors through various methods, such as efforts to avoid stressful situations28. Therefore, individuals experiencing stressful situations may resort to using their mobile phones as a means of escape. Conversely, life satisfaction is a significant indicator of subjective well-being. Furthermore, studies have unequivocally demonstrated a negative association between mobile phone addiction and life satisfaction29, suggesting that excessive mobile use may reduce overall life satisfaction due to its adverse effects of well-being. Despite the associations among mobile phone addiction, perceived stress, and life satisfaction, few studies have explored the mediating role of mobile phone addiction in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Moreover, there is a positive association between mobile phone addiction and physical inactivity30. Coincident the widespread intrusion of mobile phones into daily life, physically inactivity has become a prevalent issue across various populations, affecting not only adults31 and adolescents32. For instance, a study found that approximately four in ten college students were identified as physically inactive across 23 countries33. The consequences of physical inactivity are noteworthy, being linked to various diseases, including non-communicable diseases34. The increasing prevalence of physically inactivity as a key health indicator presents a multifaceted threat to both individual well-being and public healthcare systems, contributing to a range of chronic health conditions and placing significant burdens on healthcare resources32,35. Addressing this pervasive health problem requires comprehensive strategies. One of the most pivotal approaches involves promoting and encouraging regular physical activity36. This proactive stance not only enhances individual health but also contributes to the broader goal of improving public health outcomes.

Commitment to engaging in sports proves to be a valuable strategy for enhancing an individual’s participation in physical activities. The concept of sport commitment has consistently been highlighted as a crucial factor in motivating individuals to engage in sports and remain active participants in physical activities37. Sport commitment can be conceptualized as a general psychological state that intentionally centers on the desire to persist in sports participation38. It also serves as a substantial motivational force, emphasizing a critical psychological basis for maintaining persistence39. The original sport commitment model was comprised of multiple domains, including sport enjoyment, involvement alternatives, personal investments, social constraints, and involvement opportunities38. The updated model includes 12 factors, consisting of two types of commitment and 10 sources40. In essence, sport commitment is a multifaceted construct that provides a comprehensive view, allowing for a deeper understanding of the psychological and motivational aspects that drive individuals to persist in sports participation. Moreover, sport commitment has been investigated to explore the relationship between sport commitment and commitment to social relationships41. For instance, studies have examined the relationship between sport commitment, self-determination theory, and need satisfaction to improve well-being42,43,44. Given the positive relationship found between need satisfaction and sport commitment in previous research44, it is reasonable to anticipate that sport commitment may significantly predict life satisfaction, psychological distress, and mobile phone addiction.

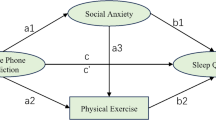

In summary, this study integrates the subjective well-being model18, sport commitment model38, and stress and coping theory27 to explore the mediating effects of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction. According to the subjective well-being model18 and stress and coping theory27, it is posited that stress is directly linked to life satisfaction; however, this connection may be influenced by mobile phone usage, as individuals experiencing elevated stress levels frequently turn to their phones to alleviate their stress. Furthermore, this mediation implies that the presence of psychopathology is necessary for the manifestation of symptoms associated with mobile phone addiction and Internet use7; consequently, mobile phone addiction subsequently diminishes life satisfaction. Thus, the first hypothesis of this study posits that mobile phone addiction mediates the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction. The second aim of this study is to examine the mediating effect of sport commitment on the relationship between life satisfaction and perceived stress, thereby addressing the existing knowledge gap. The second hypothesis of this study posits that sport commitment mediates the relationship between life satisfaction and perceived stress. Moreover, studies have revealed significant gender and age differences in variables related to mobile phone addiction and sports participation30,45. These findings emphasize the need to consider demographic factors in understanding individuals’ behaviors and attitudes toward technology and physical activity. Therefore, the third hypothesis of this study is that there are differences in gender and age among variables of mobile phone addiction, sport commitment, life satisfaction, and perceived stress. In addition, the specific hypothesis model diagram is displayed in Fig. 1. This research offers a novel contribution by integrating the concepts of sport commitment and mobile phone addiction within the context of perceived stress and life satisfaction, areas that have been underexplored in existing literature. Furthermore, this study is important not only for understanding the negative impact of mobile phone addiction but also for examining proactive strategies that can promote life satisfaction. Moreover, this study offers a comprehensive understanding of how these demographic factors influence the dynamics between mobile phone addiction, sport commitment, perceived stress, and life satisfaction. This multifaceted approach not only addresses gaps in current research but also provides valuable insights for developing targeted interventions to enhance well-being.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A cross-sectional design was adopted, utilizing convenience sampling to collect research data. After an approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (reference number: 2023013, data approved: 2023.02.22), the researchers contacted ten potential gatekeepers who worked in the Chinese universities to facilitate participant recruitment. Eight out of the ten potential gatekeepers agreed to assist in recruiting participants by sharing with their students the online survey link created by the researchers. The online survey link took participants to the study instrument which was comprised of two sections: an Informed Consent form and the survey itself. Upon agreeing to participate, respondents completed the survey. Participants were recruited from eight universities located in six Chinese cities, naming Chongqing, Maoming, Nanjing, Suzhou, Shijiazhuang, and Zhengzhou. The sample included 575 participants enrolled in Chinese university, with 309 (53.7%) being female students. Informed Consent forms were obtained from all participants. The mean age was 19.18 years (SD = 1.23). Additionally, participants’ majors were varied, encompassing fields such as computer science, physical education, and economics. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Monte Carlo Power analysis was performed via Mplus to determine the statistical power of this study. Given the novelty of this study, no existing effect sizes are available from previous literature for the mediation model. We thus performed a post-hoc power analysis using our final mediation model estimation results as the population parameter, and 1000 replications were used. Results showed that with n = 575, the estimations of all the paths in the mediation model had reached statistical power of at least 90%, indicating that our study is well powered.

Measures

Perceived stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was utilized to assess the extent to which an individual’s life stress is linked with experiences such as overload24. The PSS consists of 10 items, with four items phrased positively and six negatively24,46, and pervious literature was comprised of positively worded and negatively worded subscales among Chinse university students46. In addition, previous research has demonstrated, using factor analysis, that positively worded and negatively worded items form separate latent factors46,47. The Chinses version of the PSS was translated from English48, demonstrating a good validity and reliability within the Chinese population. In this study, we adopted the six negatively worded items for measuring perceived stress due to the following considerations: (1) the negatively worded items are more aligned with the direction of stress, for example, “How often you have felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them”, which helps circumvent potential comprehension bias caused by reversely-worded items; (2) the negatively worded subscale has better psychometric properties compared to the positively worded subscales. Moreover, the negatively worded items consist of six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.75, indicating acceptable internal consistency. The average score across these items was used as an observed variable.

Sport commitment

The Sport Commitment Scale (SCS), developed by Chen and Li49, was formulated based on the theory of sport commitment and sport commitment scale developed by Scanlan et al.38. The primary aim of the instrument was to measure and predict the physical activity of Chinese college students, with the SCS indicating good validity and reliability within this population49. The SCS consists of 5 factors: sport commitment, sport enjoyment, personal investments, social constraints, and involvement opportunities, encompassing a total of 15 items. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The present study was used the SCS to measure sport commitment among Chinese college students. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93, indicating high internal consistency. The composite score was calculated by averaging across the items.

Mobile phone addiction

The Mobile Phone Addiction Tendency Scale (MPATS), developed by Xiong et al.50, was used to assess mobile phone addiction, demonstrating good validity and reliability among Chinese college students50. The MPATS consists of 4 factors: withdrawal symptoms (6 items), salience (4 items), social comfort (3 items), and mood changes (3 items), totaling 16 items. Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher level of mobile phone addiction. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.92, indicating high internal consistency. The composite score was calculated by averaging across the items.

Life satisfaction

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al.51, contains 5 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The present study was utilized the SWLS to measure Chinese college students’ life satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, indicating good internal consistency. The composite score was calculated by averaging across the items.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation were used to characterize demographic information and study variables. Harman’s single factor test was used to check the common method bias among the model variables except for the demographic covariates. We found that the first eigenvalue explained 46.1% of the total variance, not exceeding the cutoff point of 50%52, indicating that the common method bias is not of a major concern. Then, using Mplus53, path analysis within the structural equation modeling framework was adopted to fit the proposed mediation model where mobile phone addiction and sport commitment served as the multiple mediators in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction. Age and gender served as the covariates in the model. Model fit was evaluated by indices of comparative fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Decent model fit was indicated by CFI and TLI values of above 0.95, and RMSEA and SRMR values of less than 0.0854. To test the mediating effects, a bootstrapping procedure was used with 1000 samples, and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained to test the statistical significance of indirect effects.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations among demographic and model variables. Mobile phone addiction (M = 2.57 out of a 1–5 scale) and sport commitment (M = 3.49 out of a 1–5 scale) showed moderate levels of mean value, while life satisfaction (M = 4.60 out of a 1–7 scale) had moderate-to-high level of mean value. Female was significantly and negatively related to sport commitment (r = − .20, p < .01), and age was significantly and positively related to sport commitment (r = .15, p < .01). Perceived stress had significant and positive relationship with mobile phone addiction (r = .45, p < .01), and negative relationship with sport commitment (r = − .15, p < .01) as well as life satisfaction (r = − .33, p < .01). Mobile phone addiction was significantly and negatively related to sport commitment (r = − .25, p < .01) and life satisfaction (r = − .25, p < .01). Sport commitment and life satisfaction were significantly and positively associated (r = .23, p < .01).

The proposed path analysis model showed satisfactory goodness-of-fit, χ2 (1) = 0.13, p = .724, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, 90% CI = [0.000, 0.079], and SRMR = 0.003. Figure 2 displays the standardized path coefficients. Perceived stress was significantly and positively associated with mobile phone addiction (β = 0.44, p < .001), which in turn negatively affected life satisfaction (β = − 0.09, p < .05). Perceived stress was significantly and negatively associated with sport commitment (β = − 0.15, p < .01), which in turn positively affected life satisfaction (β = 0.20, p < .001). A direct and negative effect was also observed from perceived stress to life satisfaction (β = − 0.26, p < .001). Additionally, The two parallel mediators, mobile phone addiction and sport commitment were significantly and negatively correlated (β = − 0.19, p < .001).

Regarding the effects from covariates, female was significantly and positively related to mobile phone addiction (β = 0.08, p < .05) and life satisfaction (β = 0.11, p < .01), and negatively related to sport commitment (β = − 0.19, p < .001). In addition, age was significantly and positively associated with sport commitment (β = 0.13, p < .01), and negatively affected life satisfaction (β = − 0.08, p < .05).

Table 2 shows the indirect effects of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment. The total indirect effect from perceived stress to life satisfaction was β = -0.07, p < .01, 95% CI = [-0.13, -0.03], and the direct effect was 0.26, summing up to a total effect of 0.34. The indirect effect through mobile phone addiction was negative and significant, β = − 0.04, p < .05, 95% CI = [-0.09, -0.01], accounting for 11.8% of the total effect. Additionally, the indirect effect through sport commitment was negative and significant, β = − 0.03, p < .01, 95% CI = [-0.06, -0.01], accounting for 8.8% of the total effect. The total indirect effect accounted for 20.6% of the total effect. The multiple mediation model results indicated that mobile phone addiction and sport commitment partially mediated the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Discussion

The primary aim of the study was to examine the relationships amongß perceived stress, sport commitment, mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction, controlling for the demographic variables of gender and age. Our path analysis revealed that both mobile phone addiction and sport commitment mediate the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction, supporting H1 and H2. Additionlly, our findings demonstrated significant associations among gender, age, and the variables studied, aligning with H3. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing mobile phone addiction and sport commitment for promoting both individual and public health, while also highlighting the significance of considering gender and age when exploring the complex relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

The current study uncovered a significant relationship between perceived stress, mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction. Our finding revealed mobile phone addiction plays a crucial role as a mediator between perceived stress and life satisfaction. We found a positive correlation between mobile phone addiction and perceived stress, which aligns with a research study reported by Liu et al.55. This indicated that individuals who use their phones excessively tend to experience higher levels of stress. Additionally, the findings observed a negative correlation between mobile phone addiction and life satisfaction, which was consistent with the reports of a previous study conducted by Vujic and Szabo56. This suggested that those who are addicted to their phones tend to report lower levels of satisfaction with their lives. Moreover, our stduyfindings are consistent with previous research57,58 by reporting a negative association between perceived stress and life satisfaction. This implied that individuals experiencing higher levels of perceived stress are likely to report lower levels of life satisfaction. Our findings shed light on the intricate dynamics among perceived stress, mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction, highlighting the detrimental effect of excessive phone use on well-being.

College students, who are navigating the early stages of young adulthood while facing heightened social and financial responsibility59, often experience significant stress. This stress can drive them to seek solace or distraction through their mobile phones, leading to increased usage. Mobile phones are not only incredibly convenient and accessible60, but they have also become indispensable for daily tasks such as making payments for services like deliveries and express options61. Consequently, the combination of elevated stress levels and the demands of modern life may contribute to the development of mobile phone addiction among college students, which has been linked to decreased life satisfaction.

Our results suggested that higher levels of perceived stress were associated with increased mobile phone addiction, and in turn, this elevated mobile phone usage negatively impacts life satisfaction. College students may engage in both occasional and frequent uncontrolled use of mobile phones when experiencing elevated stress levels. They might turn to their mobile phones as a means of escaping challenging circumstances or finding social support when facing psychological difficulties62. Additionally, some individuals might prioritize relationships within the virtual realm over real-world connections63. These patterns of uncontrolled usage might lead to mobile phone addiction, characterized by problematic behaviors64. Moreover, it is crucial to examine the theoretical foundations that underpin the proposed relationships between variables in this study. Although it is acknowledged that mobile phone addiction can induce stress, this study emphasizes the pathway from perceived stress to mobile phone addiction for several reasons. Stress frequently acts as a primary trigger for seeking immediate relief through readily accessible resources, such as mobile phones60,62. The immediate availability and accessibility of mobile phones make them an appealing coping mechanism for stressed individuals65. The tendency is particularly evident among college students, who face substantial societal pressures63, increasing the likelihood that stress precedes addictive behaviors as they resort to their phones for comfort. Based on the emotion-focused coping strategy within stress and coping theory27,28, individuals experiencing higher levels of stress are more likely to use their mobile phones as a means of escaping stressful situations. Consequently, excessive mobile phone use may represent an unhealthy coping strategy for managing negative emotions caused by stress in individuals66. Ultimately, both stress and mobile phone addiction are likely to contribute to a decline in life satisfaction among college students, owing to the negative association between stress, mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction. Our research extends the existing literature by highlighting the mediating role of mobile phone addiction in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction, particularly among the Chinese college student population.

Moreover, our findings elucidated that sport commitment plays a crucial role in mitigating the negative impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction among Chinese college students. Essentially, this means that individuals who are highly committed to sports tend to experience higher life satisfaction levels, even when facing elevated stress levels. This finding is significant as it sheds light on the potential protective role of sport commitment in maintaining mental well-being. The findings provide support for the idea that promoting sport commitment could be an effective strategy for enhancing life satisfaction, particularly among college students experiencing stress. This aligns with previous research conducted by Murillo et al.67, Tian and Shi68, and Wilson et al.69, which reported positive associations among sport commitment and various health indicators. For instance, Murillo et al.67, found a positive relationship between sport commitment and need satisfaction among water polo players, while Tian and Shi68 reported a similar positive relationship with social support among Chinese college students. Our study contributes to this body of knowledge by highlighting not only the positive correlation between sport commitment and life satisfaction but also its role as a partial mediator between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Furthermore, the study revealed a negative association between sport commitment and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students. The findings suggest that those who excessively and uncontrollably use their mobile phones tend to have lower levels of commitment to sports. The findings extend our understanding of the theory of sport commitment proposed by Scanlan et al.38. Moreover, previous research primarily focused on investigating the relationships between sport commitment, mobile phone addiction, and physical activity. For instance, Pereira et al.30 reported a positive correlation between mobile phone addiction and physical inactivity, while Choi70 found positive relationships between sport commitment, participation motivation factors, and sustained participant intention among university students. In essence, our findings indicated that mobile phone addiction may detrimentally impact sport commitment, leading to reduced engagement in physical activity. These insights are crucial for designing interventions aimed at promoting physical activity among college students, thereby enhancing their overall well-being.

Also, the research illustrated a significant association among gender, age, and the variables under investigation. Specifically, the findings indicate females tend to positively predict mobile phone addiction and life satisfaction, while negatively predicting sport commitment. Moreover, age positively predicts sport commitment and negatively predicts life satisfaction. These findings contrast with a study conducted by Billieux et al.64, which reported that gender was not a predictor of problematic mobile phone use. However, this inconsistency may be attributed to differences in study populations. Indeed, research indicates that gender plays a significant role in predicting mobile phone addiction71, and a study identified gender differences in smartphone usage among Chinese college students61. Furthermore, our findings align with the study conducted by Tian and Shi68, who reported that males had higher levels of sport commitment than females among Chinese college students. In summary, our study enhances understanding of how gender and age influence mobile phone addiction, perceived stress, life satisfaction, and sport commitment among Chinese college students.

Implications

The study not only contributes theoretical insights but also offers practical implications. First, it illuminates the pathways through which mobile phone addiction and sport commitment mediate the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction. These findings highlight the urgent need to address these factors to promote mental well-being of college students. Mitigating mobile phone addiction and fostering sport commitment could significantly enhance life satisfaction, especially among those facing heightened stress levels. Second, recognizing the correlations among gender, age, and the variables studied can inform tailored interventions. For instance, interventions targeting mobile phone addiction should consider gender differences in smartphone usage patterns. Third, the positive associations between sport commitment and various health indicators suggest that encouraging participation in sport and physical activities could be an effective strategy for enhancing overall health and well-being among college students. Thus, health promotion programs should prioritize initiatives that foster engagement in sports and physical activities among this demographic.

Limitations

Some limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, while the cross-sectional design offers valuable insights, it limits the ability to establish causality between variables. Future longitudinal studies could provide stronger evidence of the relationships examined. Moreover, although this study employed a cross-sectional design and convenience sampling technique, which might not yield a fully representative sample of the broader population of Chinese university students, it aimed to include participants from eight universities located in six different cities in China, reflecting diverse geographic and demographic backgrounds to capture a wide range of perspectives. Future research should consider implementing a random sampling technique to ensure a more representative sample. Second, the study’s reliance on a sample of Chinese college students may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Replicating the study with diverse samples would enhance the generalizability of the results. Finally, the absence of control for specific confounding variables, such as socioeconomic status and academic performance, limits the depth of understanding of the relationship studied. Future research should consider and control for these factors to elucidate their impact accurately.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the complex relationships among perceived stress, mobile phone addiction, sport commitment, and life satisfaction in Chinese college students. By emphasizing the mediating roles of mobile phone addiction and sport commitment, our findings underscore the importance of addressing these factors in interventions aimed at encouraging college students’ well-being. Addressing these aspects through targeted interventions could enhance the overall health and fulfillment of college students, hence contributing to their success during this critical development stage.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M. X., upon reasonable request.

References

Chan, M. Mobile-mediated multimodal communications, relationship quality and subjective well-being: an analysis of smartphone use from a life course perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 87, 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.027 (2018).

Cha, E. & Seo, B. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open. 5, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102918755046 (2018).

Chen, H. & Li, X. The contribution of mobile social media to social capital and psychological well-being: examining the role of communicative use, friending and self-disclosure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 75, 958–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.011 (2017).

Cao, X., Masood, A., Luqman, A. & Ali, A. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 85, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.023 (2018).

Online document China Internet Network Information Center. The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development (2023). https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2023/0828/c88-10829.html

Billieux, J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: a literature review and a pathways model. Curr. Psychiatry Reviews. 8, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340012803520522 (2012).

Davis, R. A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 17, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8 (2001).

Han, S., Kim, K. J. & Kim, J. H. Understanding nomophobia: structural equation modeling and semantic network analysis of smartphone separation anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw. 20, 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0113 (2017).

Kuang-Tsan, C. & Fu-Yuan, H. Study on relationship among university students’ life stress, smart mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction. J. Adult Dev. 24, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-016-9250-9 (2017).

Kaya, F., Bostanci Daştan, N. & Durar, E. Smart phone usage, sleep quality and depression in university students. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 67, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020960207 (2021).

Lopez-Fernandez, O., Honrubia-Serrano, L., Freixa-Blanxart, M. & Gibson, W. Prevalence of problematic mobile phone use in British adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw. 17, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0260 (2014).

Chen, L. et al. Mobile phone addition levels and negative emotions among Chinese young adults: the mediating role of interpersonal problems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 856–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.030 (2016).

Gao, T., Xiang, Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, Z. & Mei, S. Neuroticism and quality of life: multiple mediating effects of smartphone addiction and depression. Psychiatry Res. 258, 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.074 (2018).

Geng, Y., Gu, J., Wang, J. & Zhang, R. Smartphone addiction and depression, anxiety: the role of bedtime procrastination and self-control. J. Affect. Disord. 293, 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.062 (2021).

Li, Y., Li, G., Liu, L. & Wu, H. Correlations between mobile phone addiction and anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and poor sleep quality among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Addictions 9, 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00057 (2020).

Horwood, S. & Anglim, J. Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 97, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.028 (2019).

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E. & Oishi, S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 4, 15. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.115 (2018).

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E. & Smith, H. L. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 (1999).

Ryff, C. D. et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother. Psychosom. 75, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090892 (2006).

Balkin, R. S., Tietjen-Smith, T., Caldwell, C. & Shen, Y. P. The utilization of exercise to decrease depressive symptoms in young adult women. ADULTSPAN J. 6, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0029.2007.tb00027.x (2011).

Chan, E. S. et al. Biochemical and psychometric evaluation of self-healing Qigong as a stress reduction tool among first year nursing and midwifery students. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 19, 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.08.001 (2013).

Rayle, A. D. & Chung, K. Y. Revisiting first-year college students’ mattering: social support, academic stress, and the mattering experience. J. Coll. Student Retention: Res. Theory Pract. 9, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.2190/X126-5606-4G36-8132 (2007).

Soysa, C. K. & Wilcomb, C. J. Mindfulness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Mindfulness 6, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0247-1 (2015).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Social Behav. 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 (1983).

Denovan, A. & Macaskill, A. Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y (2017).

Peng, Y. et al. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: the mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Personality Individual Differences. 185, 111222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111222 (2022).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping (Springer, New York, 1984).

Carver, C. S. & Connor-Smith, J. Personality and coping. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 61, 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352 (2010).

Jiang, W., Lou, J., Guan, H., Jiang, F. & Tang, Y-L. Problematic mobile phone use and life satisfaction among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Shanghai, China. Front. Public. Health. 9, 805529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.805529 (2022).

Pereira, F. S., Bevilacque, G. G., Coimbra, D. R. & Andrade, A. Impact of problematic smartphone use on mental health of adolescent students: Association with mood, symptoms of depression, and physical activity. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw. 23, 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0257 (2020).

Dumith, S. C., Hallal, P. C., Reis, R. S. & Kohl, H. W. Worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and its association with human development index in 76 countries. Prev. Med. 53, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.02.017 (2011).

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M. & Bull, F. C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 4, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2 (2019).

Pengpid, S. et al. Physical inactivity and associated factors among university students in 23 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Int. J. Public. Health. 60, 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0680-0 (2015).

Lee, I. M. et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 380, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 (2012).

Ding, D. et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 388, 1311–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X (2016).

Warburton, D. E., Nicol, C. W. & Bredin, S. S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 174, 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351 (2006).

Berki, T., Piko, B. F. & Page, R. M. Hungarian adaptation of the sport commitment questionnaire-2 and test of an expanded model with psychological variables. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 86, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2020-0009 (2020).

Scanlan, T. K., Carpenter, P. J., Schmidt, G. W., Simons, J. P. & Keeler, B. An introduction to the sport commitment model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 15, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.1.1 (1993).

Carpenter, P. J., Scanlan, T. K., Simons, J. P. & Lobel, M. A test of the sport commitment model using structural equation modeling. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 15, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.2.119 (1993).

Scanlan, T. K., Chow, G. M., Sousa, C., Scanlan, L. A. & Knifsend, C. A. The development of the sport commitment questionnaire-2 (English version). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 22, 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.002 (2016).

Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. et al. Adapting the Sport Commitment Questionnaire-2 for Spanish usage. Percept. Motor Skills. 126, 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512518821822 (2019).

Hu, Q., Li, P., Jiang, B. & Liu, B. Impact of a controlling coaching style on athletes’ fear of failure: Chain mediating effects of basic psychological needs and sport commitment. Front. Psychol. 14, 1106916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1106916 (2023).

Hodge, K., Chow, G. M., Luzzeri, M., Scanlan, T. & Scanlan, L. Commitment in sport: motivational climate, need satisfaction/thwarting and behavioural outcomes. Asian J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 3, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsep.2023.03.004 (2023).

Pulido, J. J., Sánchez-Oliva, D., Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., Amado, D. & García-Calvo, T. Sport commitment in young soccer players: a self-determination perspective. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching. 13, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954118755443 (2018).

Li, Y., Ma, X., Li, C. & Gu, C. Self-consistency congruence and Smartphone Addiction in adolescents: the mediating role of Subjective Well-Being and the moderating role of gender. Front. Psychol. 12, 766392. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.766392 (2021).

Lu, W. et al. Chinese version of perceived stress Scale-10: a psychometric study in Chinese University. PloS One. 12, e0189543. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189543 (2017).

Ng, S. M. Validation of the 10-item Chinese perceived stress scale in elderly service works: one-factor versus two-factor structure. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-1-9 (2013).

Yang, T. & Huang, H. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 24, 760–764 (2003).

Chen, S. P. & Li, S. Z. Research on the test of the sport commitment model under the sport participations among college students in China. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 29, 623–625 (2006).

Xiong, J., Zhou, Z. K., Chen, W., You, Z. Q. & Zhai, Z. Y. Development of the mobile phone addiction scale for college students. Chin. Mental Health J. 26, 222–225. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2012.03.013 (2012).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 (1985).

Harman, D. A single factor test of common method variance. J. Psychol. 35, 359–378 (1967).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide8th. (Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Liu, Q. et al. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 87, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.006 (2018).

Vujic, A. & Szabo, A. Hedonic use, stress, and life satisfaction as predictors of smartphone addiction. Addict. Behav. Rep. 15, 100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100411 (2022).

Kim, B. & Kang, H. S. Differential roles of reflection and brooding on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: a serial mediation study. Personality Individual Differences. 184, 111169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111169 (2022).

Zheng, Y., Zhou, Z., Liu, Q., Yang, X. & Fan, C. Perceived stress and life satisfaction: a multiple mediation model of self-control and rumination. J. Child. Family Stud. 28, 3091–3097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01486-6 (2019).

Civitci, A. Perceived stress and life satisfaction in college students: belonging and extracurricular participation as moderators. Procedia - Social Behav. Sci. 205, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.077 (2015).

Cho, H., Kim, D. J. & Park, J. W. Stress and adult smartphone addiction: mediation by self-control, neuroticism, and extraversion. Stress Health. 33, 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2749 (2017).

Zhai, X. et al. Associations among physical activity and smartphone use with perceived stress and sleep quality of Chinese college students. Mental Health Phys. Activity. 18, 100323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100323 (2020).

Ran, G., Li, J., Zhang, Q. & Niu, X. The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: a three-level meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 130, 107198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107198 (2022).

Cikrikci, O., Griffiths, M. D. & Erzen, E. Testing the mediating role of phubbing in the relationship between the big five personality traits and satisfaction with life. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 20, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00115-z (2022).

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L. & Van der Linden, M. The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behav. Res. Therapy. 48, 1085–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008 (2010).

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C. & Hall, B. J. Problematic smartphone use: a conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 207, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030 (2017).

Wang, J., Rost., D. H., Qiao, R. & Monk, R. Academic stress and smartphone dependence among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105029 (2020).

Murillo, M., Abós, Á., Sevil-Serrano, J., Burgueño, R. & García-González, L. Influence of coaches’ motivating style on motivation, and sport commitment of young water polo players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching. 17, 1283–1294. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221116439 (2022).

Tian, Y. & Shi, Z. The relationship between social support and exercise adherence among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating effects of subjective exercise experience and commitment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811827 (2022).

Wilson, P. M. et al. The relationship between commitment and exercise behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 5, 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00035-9 (2004).

Choi, H. H. The relationships between participation motivation and continuous participation intention: mediating effect of sports commitment among university futsal club participants. Sustainability. 15, 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065224 (2023).

Li, L. et al. The severity of mobile phone addiction and its relationship with quality of life in Chinese university students. PeerJ. 8, e8859. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8859 (2020).

Funding

We acknowledge open access funding by the Talent Scientific fund of Lanzhou University. The authors received no external funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by WK, ZY, and SS. Analysis was performed by MX. MX and XD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XD, MX, and WK revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, X., Kan, W., Song, S. et al. Perceived stress and life satisfaction: the mediating roles of sport commitment and mobile phone addiction. Sci Rep 14, 24608 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76973-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76973-y