Abstract

Earthquakes have a significant impact on groundwater environments as well as human life. However, identifying active and affected zones from seismic events using isotopic and microbial diversity indicators remains a challenging frontier. To validate the applicability of this coupled method for real-time analysis, we analyzed thoron (220Rn), radon (222Rn), microbial community compositions, and hydrochemistry in groundwater samples during the 2017 Pohang earthquake for the first time. We observed the detection of 220Rn in groundwater right before the aftershocks, with a high correlation to 222Rn concentrations. This indicates that 220Rn and 222Rn can serve as reliable seismic indicators for real-time analysis. The microbial data can assist in identifying affected groundwater zones, particularly when real-time detection of 220Rn is not feasible. At the phylum level, Peregrinibacteria and Firmicutes were only found in samples with detected thoron. At the genus level, hydrogen-oxidizing or sulfur-oxidizing bacteria could serve as indicators of active zones. Two statistical analyses, self-organizing map (SOM) and principal component analysis (PCA) using hydrochemical parameters, also correlated with the results from these coupled indicators. This study demonstrates the theoretical and practical applicability of 220Rn, 222Rn, and microbial community compositions as new multi-faceted ecological indicators, whether for real-time analysis or otherwise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

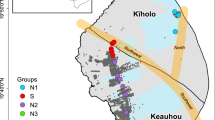

An Mw 5.5 earthquake occurred in the Pohang area of southeastern Korea on November 15, 2017. This event took place near the Pohang Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS) site, around the Yangsan fault (Fig. 1). The mainshock was identified as reverse-faulting on a WSW-ENE striking fault, at a depth of 4.0–4.5 km1,2,3. Grigoli, et al.1 this reverse fault as striking WSW-ENE with a ~ 75º dip toward the NW at a very shallow depth (4.0–5.0 km). Kim, et al.2 determined the main and subsidiary rupture planes with N36 ºE (strike)/65 ºNW (dip) and N18 ºE/60 ºNW, respectively. Subsequently, the depth of the mainshock was adjusted to 7.0–8.0 km. Hydraulic stimulation operations had been conducted at this site since January 2016, leading to debate about the causes of the Pohang earthquake. Some studies suggested that the earthquake was induced by EGS operations2,3,4,5,6, while others argued that it resulted from a combined influence of medium weakening and stress perturbation from the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake and the 2016 ML 5.8 Gyeongju earthquake5. Generally, the Korean Peninsula is considered stable with low intraplate seismic activity. The largest recorded event is the 2016 Gyeongju earthquake, which occurred since instrumental seismic monitoring began in Korea in 19037. The 2017 Pohang earthquake, however, caused extensive damage in the city. Earthquakes significantly impact groundwater systems as well as human life. Additionally, aftershocks of the Pohang earthquake occurred frequently, highlighting the need to understand hydrological responses to both the mainshock and aftershocks for effective groundwater management.

Geological map of the study area and well locations. The upper left map shows the location of the Pohang area on the southeastern Korean Peninsula. Yellow stars indicate the epicenters of the mainshocks of the 2017 Pohang earthquakes. The focal mechanisms of the two largest events from the Pohang earthquake catalog are illustrated, as determined by Woo, et al.8. Diagrams are displayed as standard equal-area projections of the lower focal hemisphere, with north at the top and compressional quadrants of the double-couple P-wave radiation pattern shaded in red. The color legend shows the lithostratigraphic units comprising the Pohang and Gyeongju areas. Major faults comprising the Yangsan Fault System are denoted with abbreviations: YSF, Yangsan Fault; MoRF, Moryang Fault; MiRF, Miryang Fault; USF, Ulsan Fault; JNF, Jain Fault.

Most previous studies have focused on earthquake forecasting and finding precursors. Hydrochemical parameters, especially isotopes, have been widely used as tracers. Among these, radon (222Rn) is commonly used as an earthquake precursor and is sampled in water or air9,10,11,12. 222Rn, a short-lived isotope with a half-life of 3.83 days, originates from rocks with high 238U content and is transported into groundwater via diffusion through rock fractures. However, despite its use in many studies, 222Rn alone is not always reliable due to its concentrations being influenced by factors such as mixing or rainfall13,14,15. Hwa Oh and Kim16 applied a radon-thoron isotope pair as an earthquake precursor in Korea. Thoron (220Rn) has a very short half-life of 55.6 s and originates from rocks with high 232Th content, also diffusing into groundwater through rock fractures. However, previous studies using the radon-thoron isotope pair were conducted in air or soil, not groundwater, due to the short half-life of thoron16,17,18,19. Only Burnett, et al.17 suggested that thoron concentrations in groundwater could be useful for interpreting earthquakes as precursors. The detection of thoron could indicate proximity to an active source, such as a fault, due to its very short half-life17. This study therefore analyzed 220Rn and 222Rn in groundwater to identify active and affected zones from seismic events, considering these isotopes not only as precursors but also in investigating hydrologic responses during seismic events.

In addition to these isotopes, microbial community compositions were analyzed to evaluate the applicability of a new multi-indicator method and to address the limitations of the isotopes’ short half-lives. Microorganisms in certain environments can be affected by environmental disturbances such as earthquakes, and microbial community compositions have been used to investigate these responses in a few studies18,20,21. However, microorganisms related to thoron and radon have rarely been identified, particularly as multiple indicators.

The main objective of this study was to propose a new coupled indicator method—using isotopes (220Rn and 222Rn) and microbial community compositions—and evaluate its applicability for investigating groundwater environment anomalies during seismic events in real-time. This research was achieved through: (1) conducting self-organizing map (SOM) statistical analysis for correlation and clustering using major ions and environmental isotopes; (2) analyzing co-seismic changes in 220Rn-222Rn concentrations in groundwater; (3) identifying microbial community compositions to reveal correlations with 220Rn-222Rn concentrations; and (4) performing principal component analysis (PCA) and examining time series data of groundwater levels to support the results from the isotopes and microbial diversity indicators.

Results

Statistical analysis of hydrogeochemistry and environmental isotopes using self-organizing map (SOM)

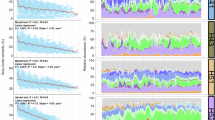

The hydrogeochemical data for 21 parameters (Na, K, Ca, Mg, Cl, NO3, SO4, HCO3, temperature, pH, DO, EC, TDS, salinity, Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, δ2H, δ18O, 222Rn, 220Rn, and4He) are summarized in Table S1. For correlation and clustering analysis, we performed SOM using major ions (Ca, K, Mg, Na, Cl, SO4, NO3, and HCO3) and environmental isotopes (Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, δ18O, δ2H, 222Rn, and 220Rn). The contribution map of the variables is shown in the component map (Fig. 2a). Each component plane represents the average value at each node, with colors indicating values; pink indicates high values and sky blue indicates low values. By comparing component planes, the planes for Ca, K, Mg, NO3, Sr, and 87Sr/86Sr showed high correlations among these variables. The planes for Na, Cl, and HCO3 also had high correlations. Notably, the planes for δ²H and δ¹⁸O, as well as 222Rn and 220Rn, showed strong correlations with each other, displaying little relationship with other variables. Additionally, clustering was conducted with a visual inspection of the U-matrix result (Fig. 2b). The pink shades on the U-matrix correspond to short distances between neighboring nodes, while sky blue shades indicate long distances between nodes. Based on these distances, the distribution of water samples could be classified into four groups: Group A (KW 8 − 1, KW 9 − 1, and MC), Group B (KW 4 − 1 and KW 4 − 2), Group C (KW 3, KW 5 − 2, KW 11 − 1, and KW 13 − 1), and Group D (KW 5 − 1, KW 7 − 2, KW 8 − 2, and KW 14).

(a) Visualization of the component planes of the hydrogeochemical data for the Pohang area from the SOM results. The pink color indicates high values of the nodes, while the sky blue color represents low values. (b) U-matrix visualization and pattern of group formation from the SOM results in the Pohang area. The label on each hexagon denotes the sample number.

Thoron (220Rn) and radon (222Rn) concentrations in groundwater

During the monitoring period, 220Rn concentrations in groundwater were detected in KW 5 − 1 (700 Bq/m3), KW 7 − 2 (120 Bq/m3), KW 8 − 1 (120 Bq/m3), KW 8 − 2 (1400 Bq/m3), KW 9 − 1 (470 Bq/m3), KW 14 (200 Bq/m3), and KW 15 (100 Bq/m3) (Fig. 3 and Table S1). These wells were sampled before the aftershocks, which occurred at 00:41:46 on November 22, 22:15:41 on November 22, 23:27:05 on November 23, and 01:17:27 on November 24, 2017. Wells KW 8 − 1, KW 8 − 2, and KW 9 − 1 were sampled before the aftershock at 22:15:41 on November 22 (Mw = 2.0), while KW 5 − 1, KW 7 − 2, KW 14, and KW 15 were sampled before the aftershocks at 23:27:05 on November 23 (Mw = 2.3) and 01:17:27 on November 24 (Mw = 2.3) (Fig. 3). Wells KW 3, KW 4 − 1, KW 4 − 2, KW 5 − 2, KW 7 − 1, KW 9 − 2, KW 11 − 1, KW 11 − 2, KW 13 − 1, KW 13 − 2, and KW 16 had thoron concentrations of 0 Bq/m2. Among these, KW 3, KW 4 − 1, KW 4 − 2, KW 13 − 1, and KW 13 − 2 were sampled on the third sampling day (November 24, 2018), not before the aftershock.

Radon concentrations in 18 groundwater wells in the Pohang area ranged from 680 Bq/m2 to 65,000 Bq/m2 (Table S1). Wells KW 5 − 1, KW 8 − 2, and KW 11 − 1 exhibited higher values compared to other wells, with the Bulguksa granite zone typically showing high radon concentrations. Significant differences in radon values were observed between alluvial and bedrock aquifer wells in KW 5, KW 8, and KW 11, while values were similar in KW 7 and KW 9. Most alluvial aquifer wells showed higher values than bedrock aquifer wells, except for KW 8, which was the only well that showed thoron detection among both types of wells.

Considering the two isotopes, 220Rn concentrations showed a positive correlation (n = 7, r2 = 0.8462) with 222Rn concentrations (Fig. 4). Despite the small sample size, this correlation between the two isotopes was very high. Anomalies, where thoron was detected with low radon activity (< 10,000 Bq/m³), were observed in KW 7 − 2, KW 8 − 1, KW 9 − 1, and KW 15. Conversely, relatively high radon concentrations with low thoron concentrations (< 1,000 Bq/m³) were observed in KW 5 − 1 and KW 14.

Microbial community compositions in groundwater

Groundwater monitoring wells were characterized for bacterial microbiota using 16 S rRNA pyrosequencing. Major microbial communities were analyzed to compare two groups at the phylum level: thoron-detected groundwater samples and non-detected groundwater samples. The averaged taxonomic compositions of the Multi-threading Parallel (MTP) sets for these two groups are shown in Fig. 5. In thoron-detected groundwater samples, the bacterial reads were affiliated with five dominant phyla: Proteobacteria, Parcubacteria_OD1, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Saccharibacteria_TM7. In non-detected groundwater samples, the bacterial reads were affiliated with five dominant phyla: Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Parcubacteria_OD1, Saccharibacteria_TM7, and Nitrospirae. Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum in both groups, representing more than 50% of the bacterial community. Peregrinibacteria and Firmicutes were observed only in thoron-detected groundwater samples, while Planctomycetes and Chlamydiae were found only in non-detected groundwater samples.

The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis also revealed differences in microbial compositions at the genus level between thoron-detected and non-detected groundwater wells (Fig. 6). This analysis identified 26 genera that were differentially abundant between the two groups. The results showed that taxa were more abundant in non-detected groundwater wells than in thoron-detected wells. Bacterial groups enriched in thoron-detected groundwater wells included Thiovirga sulfuroxydans, Thiovirga, Thioalkalibacteraceae, Hydrogenophaga, Eubacteriaceae, and Acetobacterium. Those enriched in non-detected groundwater wells included Noviherbaspirillum, Thermoleophilia, Blastocatellaceae, Rickettsiella isopodorum, CU922841_o, and HM061876_s.

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) performed on microbial community relative abundance data based on 16 S rRNA gene sequences. Negative (red bars) LDA scores represent bacterial groups in thoron non-detected groundwater samples, while positive (green bars) represent bacterial groups in thoron-detected groundwater samples. The LDA significance threshold was set to ± 2, and the log(10) transformed score is shown to illustrate the effect size. Data were analyzed and prepared using Hutlab Galaxy provided by the Huttenhower Lab.

Discussion

The detection of thoron (220Rn) indicates that the groundwater wells are influenced by source zones or active fault zones, making thoron a valuable indicator for seismic impact assessment19,22,23. In particular, our results demonstrated that 220Rn detection is effective for real-time analysis of seismic events (Fig. 3). The Self-Organizing Map (SOM) statistical analysis further supports this, showing a clear classification between thoron-detected and non-detected wells. Specifically, Groups A and D in the SOM analysis correspond to wells where thoron was detected, except for the MC sample. Conversely, Groups B and C include wells with thoron concentrations of 0 Bq/m³, indicating a clear distinction between wells influenced by seismic events and those unaffected. This highlights the potential of 220Rn as a reliable marker for identifying fault zones and fractures impacted by seismic activities. To support this interpretation, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to examine differences in geochemical processes (Fig. 7; Table 1). The PCA results revealed four principal components (PCs) that together explained 78.2% of the total variance. PC1 explained 50.1% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 8.01. It showed high positive loadings (> 0.7) for with Na, EC, Salinity, TDS, Cl and SO4, indicating potential sea water intrusion in wells KW 4 − 1, KW 4 − 2, and KW 16, which are close to surface water. PC1 also had negative loadings with 222Rn, NO3 and DO in most thoron-detected wells. PC2 explained 17.6% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 2.81. It had high positive loadings (> 0.6) for 87Sr/86Sr, Ca, Sr, K, Mg, and NO3, suggesting agricultural contamination in wells KW 9 − 1 and KW 9 − 2. PC3 accounted for 10.5% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 1.67. It showed very high positive loadings (0.8) for DO and high negative loadings for temperature (0.74) in most thoron-detected wells, possibly indicating mixing with deep upwelling geothermal water. These PCA results suggest that the differences between thoron-detected and non-detected wells are more likely attributed to hydrological changes rather than purely geochemical changes in the aquifer system. Specifically, the hydrological properties, such as temperature, seem to play a significant role in affecting the thoron detection in the groundwater samples.

The detection of thoron concentrations can be influenced by groundwater level and 4He data. The wells of KW 5 − 2, KW 7 − 1, KW 9 − 2, KW 11 − 1, KW 11 − 2, and KW 16 did not show thoron detection, even though sampling was conducted before the aftershocks. Among these, KW 16, sampled on the second day, had a low 222Rn concentration as 960 Bq/m3. Generally, values below 1,000 Bq/m3 are considered low, similar to surface water. This low concentration could be attributed to the decay of 222Rn between the sampling and measurement times due to its very short half-life. The wells KW 5, KW 7, and KW 9 exhibited unusual thoron concentration patterns, with differing results between well types. For instance, KW 5 − 1, a thoron-detected well, contrasts with KW 5 − 2, a bedrock aquifer well where thoron was not detected. This phenomenon was also observed between KW 7 − 1 and KW 7 − 2. These differences can be explained by groundwater level data (Fig. S1), which is often used to identify anomalies related to earthquakes24,25,26,27,28,29. Fig. S1 shows distinct patterns between the two types of wells. In the KW 5 wells, KW 5 − 1 experienced more significant groundwater level changes compared to KW 5 − 2, and was sampled after a slight increase in groundwater level. KW 7 − 2 also showed a gradual increase compared to KW 7 − 1. Such increases might cause thoron detection from the source zone, as turbulent water flow can generate sufficient shear stress around the 220Rn producing mineral grains30,31. Supporting these observations4, He data (Fig. S2 and Table S1) show high values in KW 5 − 1 and KW 7 − 2, indicating natural background activity from radioactivity release. Conversely, the KW 11 wells, which have high radon concentrations but no thoron detection, can be classified as non-responsive to the earthquakes.

To support the observed 220Rn activities, radon (222Rn) can serve as a supplementary indicator. The high correlation between thoron (220Rn) and radon (222Rn) concentrations suggests the useful tracer application. Given that 222Rn detection is generally easier than 220Rn detection, this correlation supports the use of 222Rn as a proxy. This high correlation was also evident in the component map from the SOM results (Fig. 2). 220Rn/222Rn ratio can be applied to differentiate between deep and shallow fracturing related to earthquakes19,32,33. For instance, anomalies where thoron is detected with low radon activity suggest that thoron is transported to the shallow subsurface from a closer source via micro-fractures. This pattern was observed in wells KW 7 − 2, KW 8 − 1, KW 9 − 1, and KW 15. Conversely, relatively high radon concentrations with low thoron concentrations may indicate a deeper, background source, as seen in KW 5 − 1 and KW 14. However, the 220Rn-222Rn pair alone is insufficient to conclusively determine whether a zone is active, as 220Rn is not always detected in all active zones associated with seismic events.

The microbial community compositions provide additional support for identifying active zones affected by earthquakes, especially when 220Rn detection is challenging. In such cases, the detection of 222Rn combined with specific microbial indicators can help identify groundwater systems impacted by seismic activity. For instance, phyla exclusively observed in groundwater samples with detectable 220Rn, such as Peregrinibacteria and Firmicutes, can be significant indicators. Peregrinibacteria is a recently identified phylum found in deep subsurface environment34,35,36. Firmicutes were identified in tsunami deposits following the Great East Japan Earthquake37 and have been recognized as a pre-earthquake indicator in the Pohang earthquake context due to their presence in deep groundwater monitoring wells at EGS sites38. Thus, these phyla are likely sourced from deep groundwater near fault zones. Conversely, phyla observed only in groundwater samples without detectable thoron, such as Planctomycetes and Chlamydiae, are typically found in more common natural environments, including aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems39,40,41. This suggests that these phyla are less likely associated with deep subsurface environments influenced by seismic activity. In the Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis, specific genera associated with 220Rn-detected groundwater samples include Thiovirga sulfuroxydans, Hydrogenophaga, Eubacteriaceae, and Acetobacterium. These genera are sulfur-oxidizing or hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria commonly found in wastewater and are not typically halophilic. Thiovirga sulfuroxydans, for instance, thrives at temperatures of 30–34 °C and shares a monophyletic lineage with phylotypes from geothermal waters42,43, making it a potential indicator of deep water upwelling due to seismic activity. Hydrogenophaga, a hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, is associated with methanogenesis in fracture zones, suggesting groundwater influenced by seismic events44,45. In contrast, genera found only in thoron non-detected groundwater samples, such as Noviherbaspirillum, Thermoleophilia, Blastocatellaceae, and Rickettsiella isopodorum, are typically aerobic and abundant in soil environments46,47. This indicates that sulfur-oxidizing or hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria are more reliable indicators of active zones influenced by seismic events, whereas the genera from non-detected samples are associated with less dynamic, more common environments.

In conclusion, the use of the 220Rn-222Rn pair proves to be a reliable method for real-time seismic activity analysis, with 220Rn detection indicating groundwater zones affected by earthquakes. However, in scenarios where 220Rn cannot be detected in real-time, microbial community composition data serve as a valuable supplementary tool. At the phylum level, Peregrinibacteria and Firmicutes emerge as effective indicators for identifying active seismic zones. At the genus level, hydrogen-oxidizing and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria are also indicative of seismic influence. This integrated approach, combining isotopic measurements and microbial community analysis, offers a robust framework for enhancing groundwater management and pinpointing affected zones during seismic events. This novel coupling method not only improves the accuracy of seismic impact assessments but also supports more informed and efficient groundwater management strategies.

Materials and methods

Site description

The Korean Peninsula is situated within the Eurasian Plate, with the Pohang basin located in the northern part of the Gyeongsang Basin. This area is part of the northern Youngnam massif and extends into the eastern part of the Yangsan fault (Fig. 1). The Gyeongsang Basin is composed of Cretaceous and Tertiary lithostratigraphic units: Middle Cretaceous Hayang Group sediments, Late Cretaceous Yucheon Group rocks, Early Miocene Yeonil Group rocks, Middle Miocene Janggi Group rocks, and Bulguksa Group granitic rocks, which intruded the Cretaceous rocks during the Late Cretaceous to Early Tertiary48,49,50. The Hayang Group consists of clastic sedimentary rocks, including shale, mudstone, and sandstone, interspersed with volcanic rocks. The Yucheon Group is predominantly composed of andesitic rocks and quartz andesites containing plagioclase phenocrysts. The Yeonil and Janggi Groups consist of Early and Middle Miocene sedimentary and volcanic rocks. The Bulguksa Group is made up of biotite granites along with grano-diorite, tonalite, and alkali-feldspar granites. Detailed data on these units can be obtained from the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM). The Yangsan Fault System comprises a series of NNE-trending major strike-slip faults with a continuous trace approximately 200 km long. The Pohang earthquakes, including the mainshock and several aftershocks, are listed in Table S2. Note that only aftershocks from November 21 to November 25, 2017, are included, as sampling was conducted between November 22 and November 24, 2017.

Groundwater wells are situated around the Yangsan Fault System in the Gyeongsang Basin (Fig. 1). Information about these wells is provided in Table S3. National groundwater monitoring wells were generally installed by the Korea Water Resources Corporation, with each point typically having one or two types of wells. A well labeled as KW ## indicates a single well type, specifically a bedrock aquifer well. Wells labeled KW ##-# consist of two types; KW ##-1 denotes an alluvial aquifer well, and KW ##-2 indicates a bedrock aquifer well. The lithostratigraphic unit describes the characteristics of the bedrock aquifer wells (labeled as KW ##-2).

Water sampling and analytical techniques

Water samples were collected from 18 groundwater wells (KW 3, KW 4 − 1, KW 4 − 2, KW 5 − 1, KW 5 − 2, KW 7 − 1, KW 7 − 2, KW 8 − 1, KW 8 − 2, KW 9 − 1, KW 9 − 2, KW 11 − 1, KW 11 − 2, KW 13 − 1, KW 13 − 2, KW 14, KW 15, and KW 16) and one surface water site (MC) over three days (November 22, 2017, to November 24, 2017), which was one week after the mainshock of the Pohang earthquakes. Each sample was collected in 4-liter polyethylene bottles using an MP-1 pump (Grundfos, USA). Geochemical parameters, including temperature, electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), total dissolved solids (TDS), pH, and salinity, were measured on-site using the YSI ProDSS digital sampling system (Xylem, USA).

After sampling, the water was filtered through 0.45-µm membranes on-site and stored in a refrigerator until analysis, except for the water used for thoron and radon measurements. Major ionic analysis was conducted using inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectrometry (ICP–AES; Varian 730–ES, Varian Inc., USA) and ion chromatography (ICS–5000; Thermo Scientific Dionex, USA) at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI). Oxygen (δ18O) and Hydrogen (δ2H) isotope ratios were measured using a VG Isotech Optima isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) and a GV Instrument Isoprime IRMS equipped with the online preparation system Euro PyrOH, respectively, at KBSI. Oxygen isotope ratios were analyzed by the equilibrium procedure between CO2 and the sample, while hydrogen isotope ratios were measured by extracting hydrogen gas from the samples using metallic strips. All 18O/16O and 2H/1H ratios are reported in delta notation relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), where δ (‰) = (R_sample/R_standard – 1) × 1000, with R representing 18O/16O or 2H/1H. For strontium isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) measurements, a Neptune MC–ICP–MS (Thermo Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) with an upgraded large dry interface pump at KBSI was used. Sample intensities were adjusted to within 10% of the standard. Strontium isotopes were measured after drying in Teflon vessels, re-dissolving in 8 M HNO3, and separating strontium from matrix elements using an Eichrom Sr resin. The total procedural blanks were negligible, less than 1 ng of Sr. The 87Sr/86Sr ratios were normalized to 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194, with the mean 87Sr/86Sr ratio of NBS987 (U.S. National Bureau of Standards) being 0.710247 ± 0.000017 (2σ, n = 18). Groundwater samples for 4He analysis were collected using copper tubes with pinch-off clamps at both ends. Gases were extracted from the water under vacuum and cryogenically purified. The concentrations of 4He were analyzed using a sector-field mass spectrometer at the University of Utah, with measurement errors of less than 1% for 4He. Thoron and radon concentrations were measured simultaneously using an RTM1688-2 (SARAD, Germany) radon and thoron monitor. A 450-ml sample of the water was placed in a 500-ml air-bubbling flask connected to the monitor in a closed air loop. Measurements were taken at 15-minute intervals for 4–6 times per sample. The equilibrium value was calibrated by adjusting the time between sampling and analysis. All water samples were analyzed within 2 hours of collection. The unit has a high sensitivity of better than 3 cpm/(kBq/m2), with a measurement error range generally less than 5%.

For microbial analysis, 13 groundwater samples (KW3, KW 4 − 1, KW 4 − 2, KW 5 − 1, KW 5 − 2, KW 8 − 1, KW 8 − 2, KW 9 − 1, KW 9 − 2, KW 11 − 1, KW 11 − 2, KW 14, and KW 15) were filtered through 0.2-µm membranes on-site. DNA was extracted using a Fast DNA Spin Kit (Qbiogen, USA) and amplified with forward and reverse primers to distinguish each sample. Pyrosequencing was conducted using a 454 GS Junior sequencing system (Roche, NJ, USA) at CJ Bioscience (Suwon, Korea). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were used to determine bacterial community structures. Each sequence was analyzed and compared with sequences in the EzTaxon-extended database (CJ Bioscience, eztaxon-e.org) via BLASTN searches and pairwise similarity comparisons. Full sequences were compared with known sequences available in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis was employed to identify taxa contributing to the effect size between microbial communities of thoron-detected groundwater samples (n = 6) and non-detected groundwater samples (n = 7) (LDA > 2.0, P < 0.05).

Continuous monitoring data for groundwater levels were provided by the National Groundwater Monitoring Network (NGMN) of the Korea Water Resources Corporation (http://www.gims.go.kr). They analyze this data every hour on the hour for two types of wells (alluvial aquifer wells and bedrock aquifer wells) or only for bedrock aquifer wells.

Statistical analysis

Self-organizing map (SOM) analysis is a powerful neural network technique used for dimensionality reduction and clustering without prior classification information51. This network consists of two layers: an input layer and an output layer, which are fully interconnected via weight vectors. The learning algorithm procedure is briefly described as follows: (i) initialize the weight vectors with small random values after determining the number of neurons; (ii) find the best-matching unit (BMU) using Euclidean distance; and (iii) update the BMU. After the simulation, the results are visualized using two types of maps: component planes and the U-matrix52. Component planes visualize the relative component values of the weight vectors, providing information about the distribution and correlations among components. The U-matrix shows the relative distances between input data, facilitating clustering analysis. The modeling was performed using the SOM Toolbox 2.0 for MATLAB 5.053. In this study, hydrochemical data (Ca, K, Mg, Na, Cl, SO4, NO3, HCO3, Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, δ18O, δ2H, 222Rn, and 220Rn) was used as input data for correlation and clustering analysis among the water samples.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is used to extract the symmetrical correlation matrix for the analyzed variables and to identify underlying structures in the multivariate dataset54,55. The variables used in this study include EC, Salinity, TDS, DO, Temperature, pH, Ca, K, Mg, Na, Cl, SO4, NO3, Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, and 222Rn. All variables, except pH, were logarithmically transformed and standardized as z-scores to reduce misinterpretation due to differences in data dimensions. Varimax rotation was applied to maximize the relationships between variables and principal components (PCs). PCs with eigenvalues greater than 1 were selected as they explain the variance. The significance of the data was tested using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests. The calculated KMO index was 0.670, indicating adequate sampling. Bartlett’s test yielded a p-value of 0.000, meeting the minimum required condition for analysis.

Data availability

All dataset was illustrated in the manuscript including supporting information file. Time series data for groundwater level, temperature, electrical conductivity was from the National Groundwater Monitoring Network (NGMN) of the Korea Water Resources Corporation (http://www.gims.go.kr). Precipitation data was obtained from the Korea Meteorological Administration, which is publicly available (direct link: https://www.kma.go.kr/w/observation/land/past-obs/obs-by-day.do).

References

Grigoli, F. et al. The November 2017 M w 5.5 Pohang earthquake: a possible case of induced seismicity in South Korea. Science 360, 1003–1006 (2018).

Kim, K. H. et al. Assessing whether the 2017 M w 5.4 Pohang earthquake in South Korea was an induced event. Science 360, 1007–1009 (2018).

Lee, K. K. et al. Managing injection-induced seismic risks. Science 364, 730–732. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax1878 (2019).

Choi, J. H. et al. Surface deformations and rupture processes associated with the 2017 mw 5.4 Pohang, Korea, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 109, 756–769 (2019).

Hong, T. K., Lee, J., Park, S. & Kim, W. Time-advanced occurrence of moderate-size earthquakes in a stable intraplate region after a megathrust earthquake and their seismic properties. Sci. Rep. 8, 13331 (2018).

Song, S. G. & Lee, H. Static slip model of the 2017 M w 5.4 Pohang, South Korea, earthquake constrained by the InSAR data. Seismol. Res. Lett. 90, 140–148 (2019).

Kim, K. H. et al. Deep fault plane revealed by high-precision locations of early aftershocks following the 12 September 2016 ML 5.8 Gyeongju, Korea, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 108, 517–523 (2018).

Woo, J. U. et al. An in-depth seismological analysis revealing a causal link between the 2017 MW 5.5 Pohang earthquake and EGS project. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 124, 13060–13078 (2019).

Huang, P., Lv, W., Huang, R., Luo, Q. & Yang, Y. Earthquake precursors: a review of key factors influencing radon concentration. J. Environ. Radioact. 271, 107310 (2024).

Jeong, C. H. et al. Relationship of radon-222 and chemical composition of groundwater as a precursor of earthquake. J. Eng. Geol. 28, 313–324 (2018).

Planinić, J., Radolić, V. & Vuković, B. Radon as an earthquake precursor. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 530, 568–574 (2004).

Woith, H. Radon earthquake precursor: a short review. Eur. Phys. J. Special Top. 224, 611–627 (2015).

Cook, P. G. et al. Groundwater inflow to a shallow, poorly-mixed wetland estimated from a mass balance of radon. J. Hydrol. 354, 213–226 (2008).

Hoehn, E. & Von Gunten, H. Radon in groundwater: a tool to assess infiltration from surface waters to aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 25, 1795–1803 (1989).

Kim, J. & Lee, K. K. Seasonal effects on hydrochemistry, microbial diversity, and human health risks in radon-contaminated groundwater areas. Environ. Int. 178, 108098 (2023).

Hwa Oh, Y. & Kim, G. A radon-thoron isotope pair as a reliable earthquake precursor. Sci. Rep. 5, 13084 (2015).

Burnett, W. et al. Measuring thoron (220 Rn) in natural waters. Measurements 7, 8 (2007).

Kim, H. et al. Impact of earthquake on the communities of bacteria and archaea in groundwater ecosystems. J. Hydrol. 583, 124563 (2020).

Yang, T. et al. Variations of soil radon and thoron concentrations in a fault zone and prospective earthquakes in SW Taiwan. Radiat. Meas. 40, 496–502 (2005).

Uprety, S., Hong, P. Y., Sadik, N., Dangol, B. & Nguyen, T. H. The effect of the 2015 earthquake on the bacterial community compositions in water in Nepal. Front. Microbiol. 8, 297371 (2017).

Yang, H. & Lou, K. Succession and growth strategy of a spring microbial community from kezhou sinter in China. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 42, 41–45 (2011).

Jaishi, H. P., Singh, S., Tiwari, R. P. & Tiwari, R. C. Radon and thoron anomalies along Mat fault in Mizoram, India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 122, 1507–1513 (2013).

Kumar, G., Kumari, P., Kumar, A., Prasher, S. & Kumar, M. A study of radon and thoron concentration in the soil along the active fault of NW Himalayas in India. Ann. Geophys. 60, S03291–S032912 (2017).

Ben-Zion, Y. & Aki, K. Seismic radiation from an SH line source in a laterally heterogeneous planar fault zone. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 80, 971–994 (1990).

Brodsky, E. E., Roeloffs, E., Woodcock, D., Gall, I. & Manga, M. A mechanism for sustained groundwater pressure changes induced by distant earthquakes. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth 108 (2003).

Manga, M. et al. Changes in permeability caused by transient stresses: field observations, experiments, and mechanisms. Rev. Geophys. 50 (2012).

Roeloffs, E. A. Persistent water level changes in a well near Parkfield, California, due to local and distant earthquakes. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth 103, 869–889 (1998).

Shi, Z., Wang, G., Manga, M. & Wang, C. Y. Mechanism of co-seismic water level change following four great earthquakes–insights from co-seismic responses throughout the Chinese mainland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 430, 66–74 (2015).

Wang, C. Y. & Manga, M. Hydrologic responses to earthquakes and a general metric. Geofluids 10, 206–216 (2010).

Huxol, S., Brennwald, M. S., Henneberger, R. & Kipfer, R. 220Rn/222Rn isotope pair as a natural proxy for soil gas transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 14044–14050 (2013).

Huxol, S., Brennwald, M. S., Hoehn, E. & Kipfer, R. On the fate of 220Rn in soil material in dependence of water content: implications from field and laboratory experiments. Chem. Geol. 298, 116–122 (2012).

Giammanco, S., Sims, K. & Neri, M. Measurements of 220Rn and 222Rn and CO2 emissions in soil and fumarole gases on Mt. Etna volcano (Italy): implications for gas transport and shallow ground fracture. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8 (2007).

Jaishi, H., Singh, S., Tiwari, R. & Tiwari, R. Temporal variation of soil radon and thoron concentrations in Mizoram (India), associated with earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 72, 443–454 (2014).

Anantharaman, K. et al. Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system. Nat. Commun. 7, 13219 (2016).

Brown, C. T. et al. Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 523, 208–211 (2015).

Wrighton, K. Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla (337, Pg 1661, 2012). Science 338, 742–742 (2012).

Makino, A., Xu, J., Nishimura, J. & Isogai, E. Detection of Clostridium perfringens in tsunami deposits after the great east Japan earthquake. Microbiol. Immunol. 63, 179–185 (2019).

Ryu, H. S., Kim, H., Lee, J. Y., Kaown, D. & Lee, K. K. Abnormal groundwater levels and microbial communities in the Pohang enhanced Geothermal System site wells pre-and post-mw 5.5 earthquake in Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 810, 152305 (2022).

Lage, O. M. & Bondoso, J. Bringing Planctomycetes into pure culture. Front. Microbiol. 3, 30415 (2012).

Lage, O. M. & Bondoso, J. Planctomycetes and macroalgae, a striking association. Front. Microbiol. 5, 92516 (2014).

Wagner, M., Nielsen, P. H., Loy, A., Nielsen, J. L. & Daims, H. Linking microbial community structure with function: fluorescence in situ hybridization-microautoradiography and isotope arrays. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17, 83–91 (2006).

Ito, T., Sugita, K., Yumoto, I., Nodasaka, Y. & Okabe, S. Thiovirga sulfuroxydans gen. nov., sp. nov., a chemolithoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a microaerobic waste-water biofilm. Int. J. Syst. Evol. MicroBiol. 55, 1059–1064 (2005).

Yang, T., Lyons, S., Aguilar, C., Cuhel, R. & Teske, A. Microbial communities and chemosynthesis in Yellowstone Lake sublacustrine hydrothermal vent waters. Front. Microbiol. 2, 9604 (2011).

Gregory, S. P., Barnett, M. J., Field, L. P. & Milodowski, A. E. Subsurface microbial hydrogen cycling: natural occurrence and implications for industry. Microorganisms 7, 53 (2019).

Purkamo, L. et al. Dissecting the deep biosphere: retrieving authentic microbial communities from packer-isolated deep crystalline bedrock fracture zones. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 324–337 (2013).

Chaudhary, D. K., Kim, J. Noviherbaspirillum agri sp. nov., isolated from reclaimed grassland soil, and reclassification of Herbaspirillum massiliense (Lagier et al., 2014) as Noviherbaspirillum massiliense comb. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 67, 1508–1515 (2017).

Feng, L. et al. Identifying determinants of bacterial fitness in a model of human gut microbial succession. In: Proc. National Academy of Sciences 117, 2622–2633 (2020).

Chang, K. Late mesozoic stratigraphy, sedimentation and tectonics of southeastern Korea (II): with discussion on petroleum possibility. J. Geol. Soc. Korea 14, 120–135 (1978).

Chang, K. H., Woo, B. G., Lee, J. H., Park, S. O. & Yao, A. Cretaceous and early cenozoic stratigraphy and history of eastern Kyŏngsang Basin, S. Korea. Geol. Soc. J. 26, 471–487 (1990).

Chang, K. H. Cretaceous stratigraphy of Southeast Korea. Geol. Soc. J. 11, 1–23 (1975).

Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 43, 59–69 (1982).

Vesanto, J. SOM-based data visualization methods. Intell. Data Anal. 3, 111–126 (1999).

Vesanto, J. & Alhoniemi, E. Clustering of the self-organizing map. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 11, 586–600 (2000).

Cloutier, V., Lefebvre, R., Therrien, R. & Savard, M. M. Multivariate statistical analysis of geochemical data as indicative of the hydrogeochemical evolution of groundwater in a sedimentary rock aquifer system. J. Hydrol. 353, 294–313 (2008).

Davis, J. C. & Sampson, R. J. Statistics and data analysis in geology. Vol. 646. (Wiley New York, 1986).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (NRF-2021R1I1A1A0104148313) and (No. 2022R1A5A1085103). It was also supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No.2019R1A6A1A03033167). For method, it was partially supported by the Institute for Korea Spent Nuclear Fuel (iKSNF) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (NRF-2021M2E1A1099413).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY. K. made substantial contributions to the conception and original draft writing of this research under the supervision of K.K. L. All authors (JY. K., HJ. K., DI. K., and K.K. L.) participated in data collection, data analysis, partially writing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Kim, H., Kaown, D. et al. Thoron, radon and microbial community as supportive indicators of seismic activity in groundwater. Sci Rep 14, 25955 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77011-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77011-7