Abstract

Aims The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) is a valuable biomarker of acute hyperglycemia, significantly correlated with unfavorable prognosis in various conditions. However, its impact on Psoriasis has not been studied. We explored the association between SHR and long-term mortality in psoriasis patients. Methods We conducted a prospective cohort study with 288 psoriasis patients from the 2003–2006 and 2009–2014 NHANES. Participants were divided into three groups based on SHR tertiles: T1 (SHR ≤ 0.870), T2 (SHR 0.870–0.958), and T3 (SHR ≥ 0.958). Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses assessed the correlation between SHR and mortality, while restricted cubic splines explored non-linear correlations. ROC analyses determined the optimal SHR cut-off value for predicting clinical outcomes. Results Out of 288 Psoriasis patients, 38 all-cause deaths occurred during an average follow-up of 112.13 ± 45.154 months. Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that higher SHR values were linked to an increased risk of all-cause mortality (log-rank P = 0.049). A U-shaped relationship was observed between SHR and all-cause mortality (P for non-linear = 0.028). Spearman correlation revealed significant associations between SHR and WC, BMI, neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte counts, SCr, uric acid, DM and MetS (all P < 0.05). After adjusting for confounders, multivariate Cox regression showed that SHR was associated with a 10.937-fold risk of all-cause mortality. ROC curve analysis identified an optimal SHR cut-off value of 1.045 for predicting long-term all-cause mortality in psoriasis patients. Conclusions Elevated SHR value independently correlates with all-cause mortality in Psoriasis patients, displaying a U-shaped relationship with clinical endpoints. An optimal SHR cut-off value of 1.045 has been determined for predicting clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis, affecting over 60 million people worldwide, is a chronic inflammatory condition marked by itchy, scaly, red plaques that can crack and bleed1. It is triggered by factors such as skin injuries, smoking, certain drugs (including interferon and lithium), streptococcal infections, and stress, with a higher risk for those with a family history2. The etiology of Psoriasis remains complex and unclear, involving a sophisticated interplay between various immune cells and cytokines, with the IL-23-mediated activation of the TH17 pathway being particularly significant in the disease’s pathogenesis3,4. Previously considered a benign skin disease, Psoriasis is, in reality, a cluster of systemic conditions linked to obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and adverse cardiovascular events, resulting in a life expectancy up to five years shorter than those without Psoriasis5,6,7,8. The poor long-term prognosis of Psoriasis is likely due to higher inflammatory biomarkers compared to patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, leading to metabolic dysregulation and an increased incidence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and cardiovascular disease (CVD)9,10,11,12. Therefore, developing cost-effective parameters to predict unfavorable long-term outcomes in Psoriasis is crucial, reducing substantial health risks for this population.

Stress hyperglycemia, characterized by a temporary elevation in plasma glucose, is a contributor to various critical illnesses, potentially linked to oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction13,14,15,16,17. However, there are no precise determinants to accurately reflect acute glucose fluctuations, as the widely-used admission blood glucose (ABG) is limited by chronic alterations in plasma glucose levels or acute stressors13,15,16,18. Consequently, the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR), which considers both ABG levels and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), was introduced and has shown prognostic utility for adverse outcomes across various clinical conditions14,19,20,21,22. Despite this, whether the SHR can impact clinical outcomes in individuals with Psoriasis remains unclear.

Therefore, we conducted a large prospective cohort study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to assess the correlation between SHR and long-term all-cause mortality in psoriasis patients, potentially establishing SHR as a risk stratification parameter in managing these patients.

Methods

Study Population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing cross-sectional study conducted every two years to assess the health and nutritional status of the overall population. Under the auspices of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the survey’s data is continuously updated on the website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes. The study collects comprehensive data, including demographic information, physical examinations, laboratory assessments, and health and nutrition questionnaires, using advanced equipment to ensure the reliability and precision of the data.

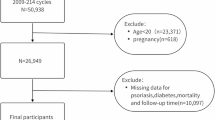

Figure S1 illustrates the recruitment process for a total of 50,939 individuals from the years 2003–2006 and 2009–2014. Exclusions were made for those under the age of 18 (n = 21,251), those with incomplete SHR (fasting plasma glucose (FPG), HbA1c) data (n = 13,984), those lost to follow-up (n = 13), and those without self-reported Psoriasis data or non-Psoriasis data. After the screening process, 288 individuals who met the eligibility criteria for Psoriasis were included in the final analysis.

All surveys underwent thorough review and approval by the NCHS Ethics Review Committee, and all participants provided written informed consent prior participation.

Calculation of SHR and grouping

The FPG was obtained in the morning after 9 h. Based on the previous research23, the SHR is calculated using the following equation by dividing ABG by the estimated average glucose, which eventually equals [(ABG (mmol/L) / [1.59 × HbA1c (%) − 2.59] 24. All subjects were subsequently divided into three groups (T1, T2, and T3) based on tertile thresholds calculated according to SHR, which were determined to be 0.870 and 0.958.

All-cause mortality assessment

In our prognostic analysis, all-cause mortality was regarded as a primary outcome. According to the International Classification of Disorders, Tenth Revision (ICD–10), all-cause mortality encompassed more than 10 diseases ranging from cardiovascular diseases to nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis. Relevant mortality information is accessible at the following website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality.htm.

Variable assessment

The NHANES demographic questionnaire was employed to acquire information from respondents concerning gender, age, ethnicity, and level of education. Race/ethnicity was stratified into Mexican American, non-Hispanic White/Black, and others (Hispanic, Asian and multiracial). Education status was simplified into three categories: less than high school, high school degree, and more than high school. Smoking status is defined as never, former, or current. Alcohol consumption is simply classified into yes or no. Information regarding a history of DM, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and MetS was collected through self-report questionnaires, among which MetS was defined according to the requirements outlined by the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III). Moreover, blood pressure was measured three times by a qualified physician to determine the average value, and WC as well as body mass index (BMI) measurements were obtained through standardized procedures at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) by trained health technicians. Additionally, various laboratory counts such as white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte, as well as levels of total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG), FPG, HbA1c, C-reactive protein (CRP), serum creatinine (SCr), Uric acid, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), total bilirubin and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) assessed in the NHANES laboratory.

Statistical analyses

Data analyzed in our investigation has been conducted using suitable sample weights following the guidelines outlined in the NHANES database. Mean ± standard deviation was utilized for continuous variables, while counts and percentages (%) were applied for the categorical variables. An ANOVA was conducted to compare the continuous variables between SHR tertile groups. Depending on the circumstance, Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. The Spearman correlation test was used to seek linear relations between SHR and other clinical risk factors as well as a multicollinearity analysis was applied. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to analyze independent clinical risk factors associated with all-cause mortality in psoriasis respondents by selecting the potential risk factors listed in Table 2 (Age, Sex, Ethnicity, Waist circumference (WC), BMI, WBC, Neutrophil, Lymphocyte, Monocyte, CRP, FPG, HbA1c, SCr, Uric acid, BUN, AST, DM, MetS, SHR as continuous and SHR tertile). The multivariate analysis employed the forward stepwise regression methodology to compensate for significant clinical variables (P < 0.10) identified in the univariate study and previously known risk factors. The estimated hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were applied in the analysis. The evaluation of time-related mortality was visualized using the Kaplan-Meier technique, and differences were ascertained using log-rank testing. A limited cubic spline regression for HR was conducted to examine the link between SHR and mortality in the non-linear relationship. Additionally, the ideal SHR cut-off value and matching area under the curve (AUC) were determined using the receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis in order to forecast clinical outcomes based on the Youden index. A subgroup analysis investigated the relationship between the SHR and the stratified factors (age, race, education levels, marital status, Poverty Income Ratio (PIR), WC, WBC, Monocyte, BUN, DM, and MetS). An interaction P-value was also introduced to test for subgroups’ heterogeneity.

All statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.25, and figures were created using GraphPad version 9. Ink. Every analysis used a two-sided approach, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

After thoroughly analyzing the raw data from NHANES, we ultimately recruited 288 respondents diagnosed with Psoriasis. Among them, males comprised 47.6% of the total population, with an average age of 49.41 ± 16.217 years. The most prevalent ethnicity was non-Hispanic white, while non-Hispanic black was the least represented.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of the study population, classified by T1, T2, and T3 according to SHR tertiles. Compared to patients with lower SHR values, those with higher SHR values were more likely to have higher BMI and WC, a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white ethnicity, higher education levels, and a higher prevalence of DM. Additionally, individuals with higher SHR values demonstrated higher levels of lymphocytes, FPG, and HbA1c (all P < 0.05). Despite the lack of significant differences across SHR tertile groups, individuals with higher SHR values tended to be older, frequent alcohol drinkers, and have a history of hypertension, heart failure, CHD, MetS, as well as elevated laboratory parameters such as neutrophils, TG, CRP, SCr, uric acid, AST, and total bilirubin.

Predictive factors of all-cause mortality

A total of 38 patients experienced all-cause mortality during the mean follow-up period of 112.13 ± 45.154 months. We conducted univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis to identify underlying risk indicators, considering various factors. In univariate Cox regression analysis, SHR emerged as a significant prognostic indicator with a 2.343-fold increased risk (HR 2.343; 95% CI 1.026–5.353, P = 0.043) alongside confounders. Subsequently, a multivariate Cox regression analysis included some parameters with a P value below 0.1 and previously known risk factors. After adjusting for potential confounders, the T3 group remained associated with a significantly increased 10.937-fold risk of all-cause mortality (HR 10.937; 95% CI 1.314–91.014, P = 0.027) (Table 2). Furthermore, we applied three models and display HR with 95% confidence intervals (CI) categorized by SHR tertiles for all-cause mortality across the all models in Table S1, the fully adjusted model (Model 2) analysis of all-cause mortality shows that categorical SHR values were generally associated with mortality risk, exhibiting a significantly higher risk (HR: 10.937, 95% CI: 1.314–91.014, P < 0.001), while no significant trend observed across tertiles (P for trend > 0.05).

Association of SHR and clinical outcomes for all-cause mortality

Figure 1 displays the Kaplan–Meier curve, demonstrating that individuals in the higher SHR group (T3) faced a significantly increased risk of primary outcomes compared to those with lower SHR levels (log-rank P = 0.049). According to the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis mentioned above, an adjusted smoothed U-shaped restricted cubic spline plot was generated after adjusting for factors such as age, PIR, WC, ethnicity, education levels, marital status, MetS, BUN, WBC, and monocyte percentage. This plot revealed a significant non-linear correlation between SHR and adverse primary outcomes (P for non-linear = 0.028) (Fig. 2).

Multivariable adjusted spline curves for associations of the SHR with all-cause in patients with Psoriasis. Hazard ratios adjusted for age(as a continuous variable), race, PIR(as a continuous variable), WC(as a continuous variable), ethnicity, education levels, marital status, MetS, BUN(as a continuous variable), WBC(as a continuous variable), and monocyte count(as a continuous variable). The solid line and red area represent the estimated values and their corresponding 95% CI. SHR stress hyperglycemia ratio, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval.

Correlation between the SHR and other risk factors

Table S2 presents the results of a Spearman correlation test conducted to examine the relationships between SHR and other clinical risk factors. The findings revealed a positive association between SHR and WC (r = 0.205; p < 0.001), BMI (r = 0.120; p = 0.045), neutrophil count (r = 0.123; p = 0.037), monocyte count (r = 0.012; p = 0.008), SCr (r = 0.145; p = 0.014), and uric acid (r = 0.167; p = 0.005), as well as a negative correlation with lymphocyte count (r = -0.144; p = 0.014). In additon, we conducted multicollinearity analysis in Table S3. Notably, we discovered that the tolerance (TOL) of neutrophil and lymphocyte are far smaller than 1 as well as variance inflation factor (VIF) considerably higher than 10 (neutrophil: TOL 0.049; VIF 20.538; P = 0.694) (lymphocyte: TOL 0.053; VIF 18.857; P = 0.638), which indicated that there existed multicollinearity between neutrophil and lymphocyte.

The optimal cut-off value of SHR for predicting outcomes among Psoriasis

Figure 3 illustrates the ROC analysis of SHR for predicting the potential hazards of poor clinical outcomes in patients with Psoriasis. The optimal SHR cut-off value for predicting Psoriasis was determined to be 1.045, yielding an AUC of 0.615 (95% CI: 0.517–0.547; P = 0.023).

Impact of SHR on subgroups

Figure S2 examines the correlation between SHR and all-cause mortality risk through stratification and interaction analysis for various variables, including sex, education levels, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of DM, heart failure, stroke, CHD, and MetS. We observed that, except for the education levels subgroup (P for interaction = 0.857), marital status subgroup (P for interaction = 0.192), and stroke subgroup (P for interaction = 0.262), SHR interacted significantly in most of the psoriasis subgroups (P for interaction < 0.05) which may be inferred that a higher SHR value had a strong correlation with increased all-cause mortality in males (HR: 4.612, 95% CI 1.032–20.611, P = 0.022), patients frequently consumed alcohol (HR: 3.150, 95% CI 1.037–9.570, P < 0.001). However, despite no significance being observed in smoking status, DM and MetS subgroup (all P > 0.05), elevated SHR value more likely to affect the all-cause mortality in those patients who were current smokers (HR: 2.888, 95% CI 0.204–24.825) and had a history of DM (HR: 2.364, 95% CI 0.506–11.039) as well as MetS (HR: 2.798, 95% CI 0.935–8.373).

Discussion

This prospective cohort investigation is the first to examine the underlying hypothesis that SHR may deteriorate clinical outcomes for individuals with Psoriasis over an extended period. The novel findings of our study can be summarized as follows: Initially, it was confirmed that among respondents with Psoriasis, higher SHR levels were associated with an increased risk of death from all causes. Secondly, after controlling for pertinent confounding factors, SHR showed a non-linear connection with a U-shaped pattern with hazard ratios and was independently linked to the long-term risk of all-cause mortality in patients with Psoriasis. Additionally, a Spearman correlation revealed a strong relationship between SHR and several common risk variables of Psoriasis, such as WC, BMI, neutrophil count, monocyte count, lymphocyte count, SCr, and uric acid. Furthermore, with an AUC of 0.615, ROC curve analysis revealed that the optimal cut-off value for predicting clinical outcomes in the psoriasis group was 1.045. Overall, this study underscores the notion that Psoriasis is more than just a skin condition, highlighting SHR as a significant predictor of poor long-term all-cause mortality among psoriasis patients. These findings can guide rapid screenings and facilitate more intensive medical care for those psoriasis patients at risk.

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease with characteristic cutaneous alterations and systemic manifestations25. Psoriasis can take a serious and life-threatening course due to systemic inflammatory complications and its association with various comorbidities26. According to a large amount of newly published research, individuals with Psoriasis had a higher death risk when compared to the control groups27,28,29,30. Despite significant advances in standardized treatment measures for Psoriasis in recent years and a marked decrease in mortality rates among patients with Psoriasis, mortality rates remain higher than the general population31. Colaco et al. conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study involving 176,858 patients with Psoriasis (2,524 deaths), revealing a mortality rate 1.44 per 1000 population32. This elevated death rate is partially attributed to an increased prevalence of cardiovascular, infectious, and neoplastic disorders, as noted by Yevgeniy R. Semenov et al.8. Additionally, Psoriasis, while primarily a skin and joint disease, is linked to several comorbidities such as CVD, bowel disease, MetS, and DM. These associated conditions significantly accelerate the rate of all-cause mortality, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive medical care that addresses both the dermatological and systemic health risks faced by psoriasis patients33,34,35. In our investigation, over an average follow-up period of 112 months, 13.1% of all-cause mortalities were observed among Psoriasis respondents, totaling 38 cases. Given the significant mortality risks associated with Psoriasis, it is crucial to identify cost-effective predictive factors for mortality to enable effective risk stratification within this cohort.

Stress hyperglycemia, featured by a momentary elevation in blood glucose levels in response to illness-related stress, is a common occurrence among critically ill patients15. A study enrolling a total of 1099 patients diagnosed with ST-elevated myocardial infarction who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention from 2016 to 2021 discovered that stress hyperglycemia was significantly associated with an increased risk of in-hospital death and all-cause mortality36. Furthermore, Tziomalos K et al. reported that patients with stress hyperglycemia had worse functional outcomes compared to both patients with Type 2 DM and those without either stress hyperglycemia or Type 2 DM, suggesting that stress-induced hyperglycemia could serve as a significant prognostic factor, even in the presence of diabetes37. However, due to the influence of chronic glucose status, measurements of ABG or FPG may not fully capture acute hyperglycemic conditions18. Consequently, Roberts et al. introduced SHR as a novel biological biomarker specifically for acute hyperglycemia, demonstrating strong correlations with clinical outcomes across various patient populations17,38. SHR not only reflects the severity of an emergency but also indicates glucose dysregulation. Poor blood glucose regulation can jeopardize patient outcomes by exacerbating endothelial dysfunction, reducing platelet nitric oxide reactivity, aggravating microvascular blockage, and causing additional hyperglycemic-induced vascular injury18. Yang et al.18 evaluated the impact of SHR on outcomes among 5,562 acute coronary syndrome patients, demonstrating that SHR was independently associated with both short-term and long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Furthermore, another study found a U-shaped relationship between SHR and all-cause mortality, CVD, and heart failure rehospitalization in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and DM39. Additionally, according to the findings of Wei Xu et al., SHR is significantly correlated with in-hospital mortality in patients with CAD and may be a useful indicator of in-hospital mortality, especially in individuals with pre-DM and DM23,40. A large cohort study involving 2875 Chinese adults found that both high and low-stress hyperglycemia ratios (SHR) were associated with poor prognosis during hospitalization in non-surgical patients with heart failure and type 2 DM, particularly in those with impaired kidney function upon admission41. Moreover, it has been reported that in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries, elevated SHR is directly linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events, particularly in those diagnosed with DM42. However, the potential application of SHR for predicting mortality risk in psoriasis patients has not been previously studied. In this study, which included 288 patients, SHR was examined as a prognostic factor for the first time in the psoriasis group over a follow-up duration of 112 months. The results revealed a significant correlation between elevated SHR levels and an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Notably, SHR exhibited a non-linear, U-shaped relationship with hazard ratios after adjusting for relevant confounding variables and was independently associated with long-term all-cause mortality risk in psoriasis patients. Additionally, an ROC curve analysis, with an AUC of 0.615, identified 1.045 as the optimal cut-off value for predicting clinical outcomes in the psoriasis group. Patients with higher SHR values showed a significant association with higher mortality rates, particularly among male responders and individuals who regularly consume alcohol, compared to those with lower SHR values. These findings suggest the potential application of SHR in risk assessment among psoriasis patients, highlighting the importance of managing SHR levels for their health benefits.

The association between high SHR and poor outcomes among psoriasis patients is unclear. Previous data indicated that Psoriasis can be potentially life-threatening due to complications such as sepsis and multisystem organ failure43,44. These findings are consistent with our study, which shows that patients with high SHR demonstrate a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including DM, potentially linked to endothelial dysfunction, leading to poorer prognosis in some cases. Secondly, older age, greater WC, and systemic inflammation characterized by monocytes were identified as independent risk factors for all-cause mortality in psoriasis patients and were more prevalent among those with high SHR. Additionally, SHR exhibited a linear correlation with impaired renal function, as indicated by SCr and uric acid levels and inflammation, represented by neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, which may also be associated with poor prognosis. Therefore, further research is urgently needed to validate these findings in a broader psoriasis cohort and to identify the underlying mechanisms by which high SHR leads to poor prognosis in this population.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it is the first to evaluate the role of SHR during a long follow-up span and determine a U-shaped relationship between the SHR and mortality as well as obtain its cut-of value in predicting poor clinical outcomes among Psoriasis patients, which facilitates to estimate the role of SHR and the potential ability to predict poor clinical outcomes. The results enable physicians to regulate the risk factors better, enhance goal-directed medical therapy, follow up on targeted patients more precisely, and enhance the quality of life for Psoriasis patients.

However, it is important to acknowledge a few limitations associated with our study. First and foremost, the current study’s limited sample size may have constrained its results, and larger prospective investigations are required to ensure the validity of these conclusions. Second, we were unable to generalize the results to other populations worldwide since the ethnicity examined in our research was limited to the United States. Additionally, individuals lacking complete data were eliminated to determine the SHR value and select the targeted Psoriasis group, thus leading to selection bias. Moreover, even after considering a wide range of possible confounders, the impact of unmeasured confounders could not be completely avoided. Furthermore, we did not consider any additional non-insulin-based insulin resistance indicators in our original research, which was limited to examining the relationship between SHR and mortality. Last, since only ABG and HbA1c are available, our study cannot dynamically monitor the varying actual stress hyperglycemia while disregarding its long-term state.

Conclusion

This prospective cohort study indicates for the first time that SHR is an independent risk predictor associated with an unfavorable long-term prognosis of all-cause mortality in psoriasis patients. The study identified a cut-off value for predicting poor clinical outcomes and demonstrated a U-shaped correlation between SHR and clinical endpoints. These findings contribute to a more reliable and cost-effective stratification of high-risk psoriasis patients.

Data availability

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset is publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). The data analyzed in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author with a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- MetS:

-

metabolic syndrome

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- ABG:

-

admission blood glucose

- SHR:

-

stress hyperglycemia ratio

- HbA1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- FPG:

-

fasting plasma glucose

- CHD:

-

coronary heart disease

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- NCEP ATP III:

-

National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- MEC:

-

Mobile Examination Center

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglyceride

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- SCr:

-

serum creatinine

- BUN:

-

blood urea nitrogen

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- WC:

-

waist circumference

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- TOL:

-

tolerance

- VIF:

-

variance inflation factor

- PIR:

-

Poverty Income Ratio

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

References

Gelfand, J. M. Psoriasis - More Progress but More Questions. N Engl J Med 390(6), 561–2 (2024).

Armstrong, A. W. Psoriasis provoked or exacerbated by medications: identifying culprit drugs. JAMA Dermatol 150(9), 963 (2014).

Armstrong, A. W. & Read, C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA 323(19), 1945–60 (2020).

Alwan, W. & Nestle, F. O. Pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis: exploiting pathophysiological pathways for precision medicine. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33(5 Suppl 93), S2-6 (2015).

Noe, M. H., Shin, D. B., Wan, M. T. & Gelfand, J. M. Objective Measures of Psoriasis Severity Predict Mortality: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. J Invest Dermatol 138(1), 228–30 (2018).

Gelfand, J. M. et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA 296(14), 1735–41 (2006).

Elmets, C. A. et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol 80(4), 1073–113 (2019).

Semenov, Y. R. et al. Psoriasis and mortality in the United States: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 85(2), 396–403 (2021).

Arnett, D. K. et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 74(10), 1376–414 (2019).

Fernandez-Armenteros, J. M. et al. Psoriasis, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors. A population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 33(1), 128–35 (2019).

USPST et al. Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Promote a Healthy Diet and Physical Activity for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adults With Cardiovascular Risk Factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 324(20), 2069–75 (2020).

Diseases GBD, Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258), 1204–22 (2020).

Capes, S. E., Hunt, D., Malmberg, K. & Gerstein, H. C. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 355(9206), 773–8 (2000).

Marenzi, G. et al. Prognostic Value of the Acute-to-Chronic Glycemic Ratio at Admission in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Prospective Study. Diabetes Care 41(4), 847–53 (2018).

Marik, P. E. & Bellomo, R. Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response! Crit Care 17(2), 305 (2013).

Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373(9677), 1798–807 (2009).

Roberts, G. W. et al. Relative Hyperglycemia, a Marker of Critical Illness: Introducing the Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(12), 4490–7 (2015).

Yang, J. et al. The Impact of the Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio on Short-term and Long-term Poor Prognosis in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insight From a Large Cohort Study in Asia. Diabetes Care 45(4), 947–56 (2022).

Zeng, G. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and long-term prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A multicenter, nationwide study. J Diabetes 15(7), 557–68 (2023).

Sia, C. H. et al. Optimal glucose, HbA1c, glucose-HbA1c ratio and stress-hyperglycaemia ratio cut-off values for predicting 1-year mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic acute myocardial infarction patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20(1), 211 (2021).

Wang, M., Su, W., Cao, N., Chen, H. & Li, H. Prognostic implication of stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 63 (2023).

Abdu, F. A. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and poor long-term prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 11 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: insights from a large cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 217 (2022).

Xu, W. et al. Predictive value of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from a multi-center observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 48 (2022).

Ghoreschi, K., Balato, A., Enerback, C. & Sabat, R. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet 397(10275), 754–66 (2021).

Prinz, J. C. et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and mortality of generalized pustular psoriasis: A literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 37(2), 256–73 (2023).

Stern, R. S. & Huibregtse, A. Very severe psoriasis is associated with increased noncardiovascular mortality but not with increased cardiovascular risk. J Invest Dermatol 131(5), 1159–66 (2011).

Springate, D. A. et al. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of patients with psoriasis: a U.K. population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol 176(3), 650–8 (2017).

Skov, L. et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Br J Dermatol 180(1), 100–7 (2019).

Dhana, A., Yen, H., Yen, H. & Cho, E. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 80(5), 1332–43 (2019).

Chang, R. et al. Risk of autoimmune diseases in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 56, 101783 (2023).

Colaco, K. et al. Trends in mortality and cause-specific mortality among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in Ontario. Canada. J Am Acad Dermatol 84(5), 1302–9 (2021).

Davidovici, B. B. et al. Psoriasis and systemic inflammatory diseases: potential mechanistic links between skin disease and co-morbid conditions. J Invest Dermatol 130(7), 1785–96 (2010).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24(2), e13-8 (2004).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120(16), 1640–5 (2009).

Wei, Q. C. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia with clinical outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 85 (2023).

Tziomalos, K. et al. Stress hyperglycemia and acute ischemic stroke in-hospital outcome. Metabolism 67, 99–105 (2017).

Capes, S. E., Hunt, D., Malmberg, K., Pathak, P. & Gerstein, H. C. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic overview. Stroke 32(10), 2426–32 (2001).

Zhou, Q. et al. The impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality and rehospitalization rate in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 189 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and severity of coronary artery disease under different glucose metabolic states. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 29 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. ‘Stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital prognosis in non-surgical patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 290 (2022).

Gao, S., Huang, S., Lin, X., Xu, L. & Yu, M. Prognostic implications of stress hyperglycemia ratio in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. Ann Med 55(1), 990–9 (2023).

Miyachi, H. et al. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: A cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. J Am Acad Dermatol 86(6), 1266–74 (2022).

Viguier, M. et al. High frequency of cholestasis in generalized pustular psoriasis: Evidence for neutrophilic involvement of the biliary tract. Hepatology 40(2), 452–8 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to all members who contributed to the NHANES study.

Funding

This work was supported by the foundation of “Tianshan Elite” Training Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2023TSYCCX0047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A., G.T., Y.Q.and X.K. designed the study, J.A. collected and cleaned the dataset, and G.T. conducted the follow-up and verification. J.A. and G.T. drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Y.Q.and X.K. approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision read, and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NHANES is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NCHS Research Ethics Review Committee reviewed and approved the NHANES study protocol. All participants signed written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tuersun, G., Alifu, J., Qu, Y. et al. The prognostic impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio for all-cause mortality in patients with Psoriasis. Sci Rep 14, 26113 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77019-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77019-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Relationship between stress hyperglycaemic ratio (SHR) and critical illness: a systematic review

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2025)

-

U-shaped association of the stress hyperglycemia ratio with all-cause mortality and premature death in patients with cardiovascular disease: a cohort study

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)