Abstract

To improve the accuracy of photogrammetric joint roughness coefficient (JRC) estimation, this study proposes two optimization models based on ground sample distance (GSD), point density, and the root mean square error (RMSE) of checkpoints. First, an algorithm that automatically generates spatial positions for equipment based on the convergence strategy was developed, using principles of Structure from Motion and Multi-View Stereo (SfM-MVS) and the shooting parameter selection algorithm (SPSA). Second, a portable positioning plate containing ground control points and checkpoints was designed based on optical principles, and a moving camera capture strategy guided by SPSA was proposed. Combining SPSA, portable positioning plate, and moving camera capture strategy, a photogrammetric experiment for small-scale rock samples in the field was conducted, collecting 48 datasets with different shooting parameters. Subsequently, a dataset incorporating GSD, point density, RMSE, and three JRC estimation metrics was established, revealing their correlations and sensitivities. Using seven machine learning algorithms, optimization models for photogrammetric JRC accuracy were developed, with Linear Multidimensional Regression and Gaussian Process Regression models improving JRC accuracy by an average of 85.73%. Finally, the applicability and limitations of the newly proposed method were further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock surface roughness is one of the primary factors affecting the shear strength of rock joints1,2. In rock engineering projects such as dams, slopes, underground chambers, tunnels, and mines, high-accuracy characterization of the JRC is crucial for preliminary geological assessment3. With the rapid development of computer vision, optical measurement, and sensor technology, non-contact photogrammetry techniques for obtaining 3D geometric information of rocks have been widely adopted, marking significant advancements in surface acquisition technology4,5,6,7. Therefore, optimizing the accuracy of photogrammetric JRC values is essential for accurately assessing the stability of engineering rock masses.

The SfM-MVS-based photogrammetry method is widely favored and used for obtaining JRC due to its advantages over laser scanning, such as lower cost, portability, and shorter data processing time4,7,8. García-Luna et al.9 used a camera and tripod to capture images of slope rock masses and estimate the JRC. In the same year, García-Luna et al.10 conducted the 3D reconstruction of large-scale slope rock masses using unmanned aerial vehicles in the field. For small-scale rock joint roughness estimation, Paixão et al.8 detailed the application of SfM-based photogrammetry in estimating rock sample surface roughness and investigated the impact of convergence strategy in data acquisition on JRC accuracy. Ge et al.5 proposed a low-cost method for estimating rock joint roughness using a similar data acquisition strategy, comparing the performance of digital camera and smartphone in JRC estimation. They found higher accuracy with digital cameras due to their superior CCD sensors. In the same year, An et al.11 estimated a 3D roughness index \(\theta _{{\hbox{max} }}^{*}/(C+1)\) using a similar convergence strategy and proposed the moving smartphone capture method. This method significantly reduced the operational complexity of photogrammetry, although the estimated roughness accuracy was lower compared to that obtained with fixed devices.

Due to the use of the aforementioned SfM-MVS-based photogrammetry methods, JRC estimation is evolving toward lower costs and reduced operational difficulty. However, for non-professional surveyors, selecting appropriate shooting parameters in laboratory or field environments remains challenging. Additionally, regardless of the equipment or strategy used, the estimated JRC will deviate from the true value. Although some studies have investigated the impact of equipment resolution and shooting parameters on roughness parameter errors9,10,11,12, research on optimizing photogrammetric JRC accuracy remains limited. Machine learning, as a cutting-edge technology capable of handling complex nonlinear relationships under multiple parameters, offers a new perspective for optimizing photogrammetric JRC accuracy.

This study utilized SfM-MVS-based photogrammetry to investigate the impact of different shooting parameters on JRC accuracy under moving camera capture (MCC) strategy. Three parameters reflecting photogrammetric JRC accuracy were proposed: GSD, point density, and the RMSE of checkpoints. Finally, machine learning algorithms were applied to optimize JRC accuracy.

Methodology

The principle of SfM-MVS 3D reconstruction

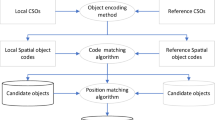

Photogrammetry methods based on SfM-MVS have been widely applied in the field of rock engineering13,14. As shown in Fig. 1, the SfM algorithm extracts feature points (\({P_{mj}}\)) from each image, matches them across different images to determine correspondences, and estimates the camera poses (\({O_m}\)) for each image. Using the camera poses and triangulation of the feature points, the 3D coordinates of the feature points in the scene are calculated15. This information is used to estimate the sparse 3D point cloud of the scene. MVS, built upon SfM, uses multi-view image information to generate depth maps containing depth values for all pixels. These depth maps are then fused into a single consistent depth map, from which a dense point cloud is generated.

Close-range photogrammetry

Specimen preparation and experimental setup

As shown in Fig. 2, a surface-unweathered, moderately undulating sandstone was used as the test subject, with dimensions of 100 × 100 × 50 mm (length × width × height). The rock was placed inside the portable positioning plate (PPP). Following the recommendations of An et al.11, the PPP includes four ground control points (GCPs) spaced 160 mm apart, which function to position and scale the point cloud. Additionally, ASPRS16 and Imaging17 suggest evaluating the reconstruction quality of the 3D point cloud using checkpoints, and recommending their uniform distribution as extensive as possible. To explore the relationship between checkpoint accuracy and the JRC, the PPP also includes twelve checkpoints (CPs). The size of the checkpoints was set to five times the GSD, as recommended by Agisoft Metashap18. GSD is defined based on image pixels as follows:

where h is the pixel size, Z is the distance from the camera to the object (i.e., shooting distance), and f is the focal length. GSD reflects the point cloud density of the target object and must be considered when determining shooting parameters8,19. The PPP is made of aluminum, offering high flatness (error ± 0.05 mm) and image accuracy (error ± 0.01 mm).

Images of the target rock were captured using a digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera, with detailed parameters provided in Table 1. Lighting conditions followed natural illumination. As shown in Fig. 2, a simple field setup was constructed for acquiring rock sample roughness.

Data acquisition based on SPSA and MCC

Based on the principles of SfM-MVS, this study integrates the SPSA proposed by Yang et al. 13 and the moving smartphone capture (MSC) mode proposed by An et al.11 to develop an algorithm that automatically generates spatial positions of the equipment according to convergence strategy.

First, as shown in Table 2, the dimensions of the target rock, GSD, and equipment parameters were input into the SPSA. Following the recommendations of Edmund Optics20, one-third of the GSD was set as the limit spatial resolution, allowing for uncertainty in the spatial accuracy of the 3D points. According to the SPSA calculations, the equipment positions for \(GSD\)= 1 are shown in Fig. 3a, and the shooting distance is sampled at an interval of 200 mm. The size and color of the position points vary with changes in the object spatial resolution error (OSRE)12. It is evident that as the shooting distance increases, the OSRE also increases, indicating that larger OSRE values correspond to larger GSD and point density, resulting in lower accuracy.

Subsequently, following the recommendations of An et al.11, a 15° angle interval was identified as optimal for image overlap at each camera position. Based on this strategy, a moving camera capture (MCC) method is proposed, utilizing a DSLR camera to conduct JRC estimation experiments at different shooting distances. Within a shooting space with a GSD of 1, a total of 24 images were captured from different positions at 15° intervals, as shown in Fig. 3a. This method generated 48 sets of rock images under different GSD conditions.

Figure 3b illustrates the actual equipment positions for the MCC strategy at a specific shooting distance. Due to the randomness of handheld collection positions, the final image overlap rate cannot be standardized. However, this generally meets the data acquisition requirements under the guidance of SfM-MVS principles18.

Data processing and JRC estimation

Rock surface reconstruction was performed using Agisoft Metashape18, a software that adheres to the principles of SfM for sparse reconstruction and MVS for dense reconstruction. The alignment accuracy in the reconstruction settings is set to the highest, and the depth maps quality and point cloud quality are set to ultra-high. The software automatically identified the positions of GCPs and adjusted the point cloud through rotation and scaling based on imported GCP coordinates. Subsequently, the point cloud underwent post-processing in CloudCompare21, where point cloud of the rock surface was extracted.

To validate the accuracy of roughness parameters at different shooting distances, a laser scanner (AutoScan-630 W) was employed to generate a point cloud of the rock surface. The measurement accuracy of the laser scanner is 0.05 mm, with point spacing in the generated point cloud can reach 0.005 mm, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. The JRC estimated from this point cloud produced by the laser scanner serves as the standard JRC value5.

In rock engineering, JRC serves as a critical parameter guiding rock quality classification and assessing rock mass stability2,22. To evaluate the estimation accuracy under different roughness calculation formulas, three JRC estimation metrics based on point cloud coordinates (JRC-1, JRC-2, JRC-3) were considered, as illustrated in Fig. 4b-d.

JRC-1 is determined based on the research by Tse and Cruden23. The JRC value for each profile (\(JR{C_{2D}}\)) is quantified using the root mean square of the first derivative (\({Z_2}\)):

where \({x_i}\), \({z_i}\), \({x_{i+1}}\), and \({z_{i+1}}\) represent the x and z coordinates of points \({i^{th}}\) and \(i+{1^{th}}\), respectively. N represents the number of points in the rock joint profile, and L denotes the length of the profile.

The overall JRC value of the entire rock joint (\(JR{C_{3D}}\)) is determined by averaging the \(JR{C_{2D}}\) values of all profiles5:

where M represents the number of profiles of the rock joint.

The \(JR{C_{3D}}\) of JRC-2 is computed according to Eq. 4, while \(JR{C_{2D}}\) is calculated based on the equation proposed by Yu and Vayssade24:

where the \({Z_2}\) is calculated using Eq. 2. Both JRC-1 and JRC-2 have a profile interval of 0.25 mm.

JRC-3 employs an alternative method to characterize 3D roughness, which aims to calculate roughness angle relationships using triangular polygonal mesh planes, considering only strike and dip angles in the analyzed orientation. JRC-3 is computed using the software developed by Magsipoc et al.25:

where \({\theta ^ * }\) represents the apparent dip angle, \(\theta\) represents the true dip angle, and \(\alpha\) represents the angle between the analysis direction and the azimuth of the normal vector.

Only the portions oriented towards the shear direction contribute to the shear strength. Therefore, the calculation of the normalized potential contact area is as follows:

where \({A_0}\) represents the normalized area in the analysis direction, \(\theta _{{\hbox{max} }}^{ * }\) represents the maximum visual dip angle, and C represents the fitting parameter.

Machine learning algorithms

A dataset was constructed using 48 sets of point clouds captured at different shooting distances. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, GSD, point density, and the root mean square error (RMSE) of checkpoints served as input parameters, while three types of JRC error were designated as output parameters. Both input and output parameters adhered to a normal distribution, with no data comprised of a limited set of specific values.

The prediction of output parameters within this dataset essentially framed a multivariate regression problem26. Consequently, this study compared the prediction results of seven machine learning models using MATLAB. 85% of the data were used as the training set, with the remaining 15% as the test set. To ensure stable convergence of generalization error within the model, the validation set is divided using the K-fold cross-validation method27,28. As depicted in Fig. 5b, five-fold cross-validation was adopted, wherein the training set was divided into five subsets, each of which could function as a validation set. This process was repeated five times, with different validation and training sets utilized for each iteration.

Support vector regression

Support Vector Regression (SVR) performs regression by finding an optimal hyperplane in a high-dimensional space. It is particularly suited for handling high-dimensional data and complex nonlinear relationships, making it useful for predicting continuous output variables29,30. Additionally, SVR exhibits good robustness to noise and performs well on small sample datasets. For nonlinear problems, SVR can utilize a kernel function to map data into a high-dimensional feature space, addressing linearly inseparable issues. These characteristics align with the sample features and the noise of the experimental environment in this study. Considering the limited size of the dataset and the three input parameters, the kernel function in this study was preset to quadratic. The kernel scale, box constraint, and epsilon were automatically selected by the algorithm, while the remaining hyperparameters were set to their default values to avoid unnecessary computational resource expenditure31.

Gaussian process regression

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a non-parametric regression method that models relationships between data based on a gaussian process model32,33. GPR does not require a predefined number of model parameters, allowing it to flexibly adapt to data complexity and avoid overfitting or underfitting. Additionally, GPR has smooth predictive capabilities, making it suitable for situations with sparse data points or noise. The characteristics of GPR are well-suited for investigating the unknown parameter mappings and the qualitatively indescribable noise in this study, such as image overlap rate, shooting angle, and lighting conditions. Considering the limited size of the dataset and the three input parameters, the kernel function in this study was preset to a rational quadratic function, utilizing an isotropic kernel. The kernel scale, signal standard deviation, and sigma were automatically selected by the algorithm, while the remaining hyperparameters were set to their default values34.

Linear multidimensional regression with interactive effect

In multiple linear regression, interaction effects refer to the influence of the interplay between two or more independent variables. If interaction effects are present, it indicates that the relationship between the independent variables is not simply additive but involves a certain degree of interaction35,36. Given the uncertainty in the relationships among the three parameters proposed in this study, a Linear Multidimensional Regression (LMR) model with interaction effects was also considered. This algorithm is suitable for small datasets and situations where the relationships between variables are approximately linear, making it easier to interpret data characteristics.

Ensemble learning

Ensemble Learning (EL) operates by generating multiple classifiers that independently learn and make predictions. These predictions are then combined into a composite prediction, outperforming any single model’s prediction37,38. This study employs the boosting algorithm, which linearly combines base models through an additive model39,40. In each iteration, the weights of the base models with low error rates are increased, while the weights of models with high error rates are decreased. The training data’s weights or probability distributions are adjusted in each round by increasing the weights of examples misclassified by the weak classifier in the previous round and decreasing the weights of correctly classified examples. This adjustment improves the classifier’s performance on previously misclassified data. The minimum leaf size was set to 8, the number of learners to 30, the learning rate to 0.1, and the rest of the hyperparameters were default values.

Neural network regression

Neural Network (NN) regression is a method that utilizes neural networks to address regression problems. Neural networks, which mimic the connection patterns of neurons in the human brain, can capture complex nonlinear relationships and possess robust learning capabilities. NN regression processes input data through a series of neuron layers, ultimately outputting continuous values41,42. Considering the limited size of the dataset and the three input parameters, the settings include one fully connected layer, with the first layer size set to 100, an iteration limit of 1,000, a regularization strength of 0, and the rest of the hyperparameters were default values.

Decision tree regression

Decision Tree (DT) regression predicts outcomes by recursively splitting the dataset, with each node representing a decision point or attribute test and each leaf node representing a prediction result43. DT regression effectively handles multi-feature nonlinear regression problems by dividing the dataset until a fitting subset is achieved, followed by linear regression modeling. The mean or median of the final leaves predicts the output. In this study, the minimum leaf size was set to 4 to achieve more accurate prediction results, while the remaining hyperparameters were maintained at their default values, taking into account the small sample size.

k-nearest neighbors regression

k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression is an instance-based learning algorithm used for solving regression problems. It predicts the target value by finding the k most similar neighbors (i.e., the closest k data points) in the feature space and using their average value44. As a non-parametric algorithm, KNN regression makes no assumptions about data distribution and can handle nonlinear data. Considering the small dataset and input parameters of this study, a least squares regression kernel learner was employed. The number of expansion dimensions, regularization strength, and kernel scale were automatically selected by the algorithm, while the remaining hyperparameters were set to their default values45.

Results

The relationship between GSD and JRC

The accuracy of this study is evaluated using the difference between the JRC values obtained from laser scanning and those obtained from photogrammetry (\(Erro{r_{JRC}}\)):

The \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) results for the three metrics (JRC-1, JRC-2, JRC-3) are depicted in Fig. 6a. It is evident that there are significant computational differences among them. Figure 6b illustrates that the 25-75% range of \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) for JRC-1 and JRC-2 remains within 2–4, while for JRC-3, some errors even fall between 4 and 6. Referring to typical roughness grading profiles based on JRC ranges2, such discrepancies are deemed unacceptable. Therefore, there is an urgent need for accuracy optimization.

Figure 6c-e reveal the relationship between GSD and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\). Due to uncertainties in image overlap rate, lighting conditions, and handheld factors under MCC strategy, \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) exhibits some dispersion with increasing GSD, yet maintains a significant correlation. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R), which evaluates the correlation between two datasets, is employed to analyze the relationship between GSD and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\).

There is a strong correlation between GSD and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) for JRC-1 (R = 0.89) and JRC-2 (R = 0.84), while JRC-3 shows a moderate correlation with an R of 0.69. \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) demonstrates greater dispersion when GSD ranges between 0.4 and 0.8. This variability is attributed to lower point cloud density and larger point density at higher GSD, resulting in unstable area estimates post grid partitioning.

Linear regression equations for GSD and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) are fitted based on their correlation. To quantitatively assess the difference in fit quality among different JRC metrics, R-squared (\({R^2}\)) is utilized as a metric to measure the goodness of fit of the regression models. As depicted in Fig. 6c-e, the regression models for JRC-1 and JRC-2 show good fit, whereas JRC-3 exhibits poorer fit due to higher data dispersion, with an \({R^2}\) of 0.48.

To further compare the significance of regression equations for different JRC metrics on GSD and \(Erro{r_{JRC}},\) this study adopts the typical roughness profile grading based on JRC ranges2, setting the threshold value for \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) at 2. Under this threshold, the corresponding GSD values represent the maximum shooting distance for a given roughness metric that meets the JRC error requirement.

In other words, a larger threshold GSD value indicates a broader range of permissible shooting distances and higher tolerance for errors under the respective device. As shown in Fig. 6f, the discrepancy in tolerance rates between JRC-1 and JRC-3 compared to that of JRC-2 is only 23.86% and 11.36%, respectively. This demonstrates the practicality of using GSD to reflect \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\).

The relationship between point density and JRC

In the study of JRC evaluation, point density to some extent reflects the accuracy of JRC5,8, defined as the reciprocal ratio of selected rock surface points to area.

Figure 7a-c present the fitting results of point density and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) under different roughness estimation methods. Unlike GSD, there is a nonlinear relationship between point density and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\), where \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) increases exponentially with larger point density. The reduced chi-squared (\({\chi ^2}\)) statistic is similarly used to assess goodness of fit, with smaller values indicating better fit. Similar to GSD, JRC-1 shows the best fit with \({R^2}\) and \({\chi ^2}\) values of 0.72 and 0.3, respectively. JRC-3 exhibits the highest data dispersion with an \({R^2}\) of only 0.46, resulting in moderate fit.

Figure 7d illustrates the threshold values of point density under different JRC estimation methods. The JRC-1 estimation method accommodates more test scenarios, yielding JRC calculations at larger intervals that meet \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) threshold requirements. Results for JRC-2 and JRC-3 are identical but differ significantly from JRC-1 by 33.33%. Hence, the JRC accuracy reflected through point density exhibits variability across different JRC estimation methods.

The relationship between RMSE and JRC

This study quantitatively evaluates the deviation between the point cloud coordinates of twelve CPs and their true coordinates using RMSE:

where \({x_{i({\text{point cloud}})}}\), \({y_{i({\text{point cloud}})}}\), \({z_{i({\text{point cloud}})}}\) represent the coordinates of the center point of CPs in the point cloud, while \({x_{i({\text{real}})}}\), \({y_{i({\text{real}})}}\), \({z_{i({\text{real}})}}\) represent the true coordinates of CPs in the PPP. n denotes the number of CPs. \(RMS{E_X}\), \(RMS{E_Y}\), \(RMS{E_Z}\) denote the errors in the X, Y, Z directions for all CPs, and \(RMS{E_R}\) represents the spatial error.

As shown in Fig. 8a-c, a linear relationship exists between \(RMS{E_R}\) and \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\), similar to GSD. However, JRC-2 exhibits the strongest correlation and best fit, with respective values of 0.87 and 0.76. JRC-1 also shows a strong correlation between these data. In contrast, JRC-3 demonstrates poorer fitting with an \({R^2}\) of 0.53. These results indicate that \(RMS{E_R}\) not only reflects the quality of point cloud reconstruction but also serves as a measure of JRC estimation accuracy.

Regarding RMSE, the differences in threshold \(RMS{E_R}\) across different JRC metrics are minimal, as depicted in Fig. 8d. The difference rate between the maximum threshold \(RMS{E_R}\) of JRC-1 and the minimum of JRC-2 is only 6%, demonstrating the universality of \(RMS{E_R}\) across various JRC estimation methods.

Discussion

Machine learning-based JRC accuracy optimization model

Based on the analysis of GSD, point density, and RMSE in Sect. 3, the relationship between \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) and these three factors has been revealed. Figure 9a further illustrates the interrelationships between the three influencing parameters and the three JRC metrics. The correlation coefficient R between JRC-1 and JRC-2 reaches 0.9, while JRC-3 shows correlations of 0.87 and 0.86 with JRC-1 and JRC-2, respectively. These correlations remain strong across different JRC estimation outcomes, indicating robust relationships among the three metrics.

Therefore, after processing with seven machine learning algorithms, the training and testing results of the models are shown in Fig. 9b and c. \(RMSE\), \(MSE\), \(MAE\), and \({R^2}\) serve as metrics for evaluating model performance:

where \({y_i}\) represents the \({i^{th}}\) observed value, \({\hat {y}_i}\) denotes the \({i^{th}}\) predicted value, \(\bar {y}\) is the mean of the observed values, and n is the number of data points. Figure 9b illustrates the comprehensive performance of each model evaluated using the integrated assessment system46. The difference in \({R^2}\) between the training and testing sets, scaled up by a factor of 10, is also depicted.

SVR, GPR, and LMR demonstrate excellent performance in JRC-1, with composite scores of 40, 41, and 44 respectively. Moreover, training and testing \({R^2}\) values exceed 0.8. Although DT and KNN exhibit relatively high composite scores of 35 and 42, with testing \({R^2}\) of 0.94 and 0.9 respectively, and their poor generalization abilities due to significant discrepancies from the training \({R^2}\) lead to inferior model performance. Similar trends are observed in the EL and NN models.

In JRC-2, SVR and LMR perform the best with a composite score of 44. GPR follows with a score of 43, but its poor generalization ability is indicated by an \({R^2}\) error of 0.31. DT shows a negative \({R^2}\) value in the testing set, indicating failure in predicting JRC-2.

Among all models in JRC-3, only the GPR model achieves training and testing \({R^2}\) values exceeding 0.5, with a composite score of 43. The remaining models exhibit poor fitting results and performances. Thus, the GPR model is the only suitable choice for predicting \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) in JRC-3.

In summary, SVR, GPR, and LMR demonstrate high performance in predicting errors for both JRC-1 and JRC-2, with GPR excelling in JRC-3 predictions. This is attributed to the flexibility of SVR and GPR in adapting to data complexity and handling nonlinear problems. Moreover, these models are suitable for scenarios with noise, aligning well with the uncertainties in this study such as image overlap rate, shooting angles, and lighting conditions. However, SVR performs poorly when faced with highly correlated features, as indicated in Fig. 9a where strong correlations between GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\) are evident. On the other hand, LMR, which considers interaction effects, effectively captures the characteristics of the three feature parameters in this dataset, thereby performing best in JRC-1 and JRC-2.

Therefore, by inputting the values of GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\) into the LMR and GPR models, the predicted \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) were obtained. Subsequently, these \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) were substituted into Eq. 9 to estimate values that approximate the standard JRC. This study calculated the discrepancies between the predicted JRC values and the standard values based on Eq. 9, with the results illustrated in Fig. 9d. Under the JRC-1, JRC-2, and JRC-3, 75% of the error results were within 1, and the median error was less than 0.5. The average accuracy of JRC improved by 91.15%, 87.99%, and 78.21%, respectively.

Analysis and results of machine learning data: (a) Correlation analysis of \(GSD\), point density, \(RMS{E_R},\) JRC-1, JRC-2, and JRC-3. (b) Comprehensive evaluation of machine learning models. (c) Performance evaluation of machine learning models. (d) Statistical distribution of optimized \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\). (e) Sensitivity analysis of \(GSD\), point density, \(RMS{E_R}\) to \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\).

Additionally, to further elucidate the sensitivity of \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) to GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\), the cosine amplitude method proposed by Yang and Zhang47 was employed:

where \({x_{an}}\) represents an input variable, \({x_{bn}}\) represents an output variable, and n denotes the sequence number of the data, with a total of 48 data sets calculated.

As illustrated in Fig. 9e, the relative effect strength (\(RES\)) of each parameter was assessed using the cosine amplitude method, with the magnitude of \(RES\) indicating the degree of influence each parameter has on JRC error values. It can be observed that the effects of the three parameters on JRC-1 and JRC-2 are nearly identical. The influences of GSD and \(RMS{E_R}\) on \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) are very similar, with an \(RES\) difference of only 0.01. The \(RES\) for point density is 0.315, representing the smallest influence among the three parameters, although it remains 0.028 lower than the \(RMS{E_R}\). For JRC-3, the influence of the three parameters is comparable to that observed for JRC-1 and JRC-2, with the maximum difference being only 0.05. Therefore, in terms of sensitivity, JRC-1, JRC-2, and JRC-3 exhibit similar sensitivities to GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\).

A comparison of the correlation results presented in Fig. 9a and the sensitivity results shown in Fig. 9e reveals notable findings. The average correlations of GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\) with JRC-1, JRC-2, and JRC-3 are 0.807, 0.713, and 0.817, respectively, as indicated in Fig. 9a. In Fig. 9e, the average \(RES\) values are 0.341, 0.317, and 0.342, respectively. The data indicate that the correlation and sensitivity of these three parameters with \(Erro{r_{JRC}}\) are similar, thereby reinforcing the significance of GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\) in both analyses. Consequently, GSD, point density, and \(RMS{E_R}\) exert a substantial influence on JRC error.

Application scopes and limitations

Small-scale rock sample photogrammetry experiments demonstrate that the newly proposed machine learning-based JRC accuracy optimization models significantly enhance photogrammetric JRC accuracy under varying shooting conditions. The algorithm for shooting parameters selection based on MCC strategy automatically generates devices’ spatial positions under different GSD, offering guidance in photogrammetric data acquisition for researchers lacking computer science expertise. Furthermore, the establishment of machine learning algorithm models aids in predicting JRC errors across three roughness metrics, leading to a substantial enhancement in photogrammetric JRC accuracy based on error outcomes. The proposed models exhibit strong robustness, accommodating uneven image overlap rate, diverse shooting distances, and lighting conditions. Thus, the newly proposed approach demonstrates high adaptability.

However, there are still limitations that need to be addressed in future work. The dataset in this study was obtained using a single camera device, and the generalizability of the results could be strengthened by considering more data acquisition devices. Additionally, the experiment subjects and data processing software were uniform, and further investigation is needed regarding results from different sizes of rock specimens and different 3D reconstruction software, although Paixão et al.11 demonstrated close results across different data processing software in their study. Therefore, when utilizing the machine learning-based accuracy optimization models proposed in this study, it is recommended to use target rock sizes and data processing software similar to those used here. Finally, the simple and efficient method proposed in this study is highly suitable for collecting and estimating JRC data from small-scale rock samples in field settings. However, there is a lack of experimental validation data in scenarios such as slopes and tunnels. Future research should focus on more comprehensive analysis and application in various rock engineering scenarios.

Conclusion

This study introduces a novel method for optimizing the accuracy of photographic measurement of JRC, achieving enhanced accuracy in JRC estimation solely through GSD, point density, and RMSE of checkpoints. The main research outcomes are as follows:

-

(1)

A convergence-based shooting parameter selection algorithm is proposed based on the SPSA. This algorithm adapts to scenarios of rock data collection guided by SfM-MVS principles. It autonomously generates camera positions relative to the target rock based on the convergence strategy, facilitating non-specialists in conducting rock data acquisition.

-

(2)

The moving camera capture strategy and a customized portable positioning plate are proposed, significantly reducing the complexity of data acquisition. The correlations between GSD, point density, RMSE, and three JRC estimation metrics are revealed through 48 field experiments under different shooting parameters. The results indicate that GSD, point density and RMSE have strong correlations with JRC-1 and JRC-2, and moderate correlations with JRC-3. Specifically, GSD and RMSE exhibit linear correlations with JRC metrics, while point density shows a power-law correlation.

-

(3)

By revealing the strong correlations between GSD, point density, RMSE, and JRC errors, two machine learning-based optimization models for photogrammetric JRC measurement under the MCC strategy are established. Utilizing predictions from the LMR and GPR models, the accuracy of the three adjusted JRC metrics is enhanced by an average of 85.73%.

Data availability

The data sets used and during the present study available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Patton, F. D. Multiple modes of shea-r failure, in Rock 1st ISRM Congress. International Society for Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, Lisbon (1966).

Barton, N. R. & Choubey, V. The shear strength of rock joints in theory and practice. Rock Mech. 10, 1–54 (1977).

Barton, N. R., Wang, C. H. & Yong, R. Advances in joint roughness coefficient (JRC) and its engineering applications. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 15(12), 3352–3379 (2023).

Battulwar, R., Zare-Naghadehi, M., Emami, E. & Sattarvand, J. A state-of-the-art review of automated extraction of rock mass discontinuity characteristics using three-dimensional surface models. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 13(4), 920–936 (2021).

Ge, Y. F., Chen, K. L., Liu, G., Zhang, Y. Q. & Tang, H. M. A low-cost approach for the estimation of rock joint roughness using photogrammetry. Eng. Geol. 305, 106726 (2022).

Xia, D. et al. An efficient approach to determine the shear damage zones of rock joints using photogrammetry. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 55(9), 5789–5805 (2022).

Ling, J. X. et al. Data acquisition-interpretation-aggregation for dynamic design of rock tunnel support. Automat. Constr. 143, 104577 (2022).

Paixão, A., Muralha, J., Resende, R. & Fortunato, E. Close-range photogrammetry for 3D rock joint roughness evaluation. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 55(6), 3213–3233 (2022).

García-Luna, R., Senent, S. & Jimenez, R. Using telephoto lens to characterize rock surface roughness in SfM models. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 54(5), 2369–2382 (2021).

García-Luna, R., Senent, S., & Jimenez, R. Characterization of joint roughness using close-range UAV-SfM photogrammetry, in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (2021b).

An, P. J., Fang, K., Zhang, Y., Jiang, Y. F. & Yang, Y. Z. Assessment of the trueness and precision of smartphone photogrammetry for rock joint roughness measurement. Measurement 188, 110598 (2022).

Yang, Q. Z., Li, A., Dai, F., Cui, Z., & Wang, H. T. Improvement of photogrammetric joint roughness coefficient value by integrating automatic shooting parameter selection and composite error model. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. (2024).

Westoby, M. J., Brasington, J., Glasser, N. F., Hambrey, M. J. & Reynolds, J. M. ‘Structure-from-Motion’photogrammetry: A low-cost, effective tool for geoscience applications. Geomorphology 179, 300–314 (2012).

Kong, D., Saroglou, C., Wu, F. Q., Sha, P. & Li, B. Development and application of UAV-SfM photogrammetry for quantitative characterization of rock mass discontinuities. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 141, 104729 (2021).

Hartley, R. I. & Sturm, P. Triangulation. Comput. Vis. Image Und. 68(2), 146–157 (1997).

American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ASPRS). ASPRS positional accuracy standards for digital geospatial data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 81(3), A1–A26 (2015).

Imaging, C. H. Guidelines for calibrated scale bar placement and processing. Version 2, 12 (2015).

Agisoft Metashape. Agisoft Metashape User Manual. https://www.agisoft.com (2022).

Kim, D. H., Poropat, G. V., Gratchev, I. & Balasubramaniam, A. Improvement of photogrammetric JRC data distributions based on parabolic error models. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 80, 19–30 (2015).

Edmund Optics. Imaging optics resource guide. (2023) https://www.edmundoptics.com/knowledge-center/industry-expertise/imaging-optics/imaging-resource-guide/# (2023).

Girardeau-Montaut, D. CloudCompare Vol. 11 (EDF R&D Telecom ParisTech, 2016).

ISRM I. Suggested methods for the quantitative description of discontinuities in rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 15(6), 319–368 (1978).

Tse, R. & Cruden, D. M. Estimating joint roughness coefficients. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 16(5), 303–307 (1979).

Yu, X. B. & Vayssade, B. Joint profiles and their roughness parameters. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 28(4), 333–336 (1991).

Magsipoc, E., Zhao, Q. & Grasselli, G. 2D and 3D roughness characterization. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 53(3), 1495–1519 (2020).

Liu, Y. S. et al. An AI-powered approach to improving tunnel blast performance considering geological conditions. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 144, 105508 (2024).

Picard, R. R. & Cook, R. D. Cross-validation of regression models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 79(387), 575–583 (1984).

Fushiki, T. Estimation of prediction error by using K-fold cross-validation. Stat. Comput. 21, 137–146 (2011).

Brereton, R. G. & Lloyd, G. R. Support vector machines for classification and regression. Analyst 135(2), 230–267 (2010).

Awad, M., Khanna, R., Awad, M., & Khanna, R. Support vector regression. Efficient Learning Machines: Theories, Concepts, and Applications for Engineers and System Designers 67–80 (2015).

Suthaharan, S., & Suthaharan, S. Support vector machine. Machine learning models and algorithms for big data classification: Thinking with examples for effective learning, 207–235 (2016).

Williams, C., & Rasmussen, C. Gaussian processes for regression. Advances in neural information processing systems, 8 (1995).

Schulz, E., Speekenbrink, M. & Krause, A. A tutorial on Gaussian process regression: Modelling, exploring, and exploiting functions. J. Math Psychol. 85, 1–16 (2018).

Williams, C., & Rasmussen, C. Gaussian processes for regression. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 8 (1995).

Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. Interaction effects in multiple regression. 72 (2003).

Siemsen, E., Roth, A. & Oliveira, P. Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ. Res. Methods 13(3), 456–476 (2010).

Dietterich, T. G. Ensemble learning. Handb. Brain Theory Neural Netw. 2(1), 110–125 (2002).

Sagi, O. & Rokach, L. Ensemble learning: A survey. Wires. Data Min. Knowl. 8(4), e1249 (2018).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. Experiments with a new boosting algorithm. icml 96, 148–156 (1996).

Mayr, A., Binder, H., Gefeller, O. & Schmid, M. The evolution of boosting algorithms. Method. Inform. Med. 53(06), 419–427 (2014).

Specht, D. F. A general regression neural network. IEEE T. Neural Netw. 2(6), 568–576 (1991).

Dreiseitl, S. & Ohno-Machado, L. Logistic regression and artificial neural network classification models: A methodology review. J. Biomed. Inform. 35(5–6), 352–359 (2002).

Xu, M., Watanachaturaporn, P., Varshney, P. K. & Arora, M. K. Decision tree regression for soft classification of remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 97(3), 322–336 (2005).

Song, Y. S., Liang, J. Y., Lu, J. & Zhao, X. W. An efficient instance selection algorithm for k nearest neighbor regression. Neurocomputing 251, 26–34 (2017).

Peterson, L. E. K-nearest neighbor. Scholarpedia 4(2), 1883 (2009).

Zorlu, K., Gokceoglu, C., Ocakoglu, F., Nefeslioglu, H. A. & Acikalin, S. Prediction of uniaxial compressive strength of sandstones using petrography-based models. Eng. Geol. 96(3–4), 141–158 (2008).

Yang, Y. & Zhang, Q. A hierarchical analysis for rock engineering using artificial neural networks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 30(4), 207–222 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The research project is financially supported by the National Youth Talent Support Program of Chongqing (No. cstc2022ycjh-bgzxm0079), Key R&D Project in Shaanxi Province (No. 2024GX-YBXM-299), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, CHD (No. 300102212207), the Research Funds of Department of Transport of Shaanxi Province (No. 23-81X), the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Architectural Cold Climate Energy Management, Ministry of Education (No. JLJZHDKF022023004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qinzheng Yang: Methodology, Writing – original draft. Ang Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.Yipeng Liu: Software, Resources.Hongtian Wang: Investigation, Resources.Zhendong Leng: Software, Formal analysis. Fei Deng: Software, Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Q., Li, A., Liu, Y. et al. Machine learning-based optimization of photogrammetric JRC accuracy. Sci Rep 14, 26608 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77054-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77054-w