Abstract

A model for predicting slope stability is developed using Categorical Boosting (CatBoost), which incorporates 6 slope features to characterize the state of slope stability. The model is trained using a symmetric tree as the base model, utilizing ordered boosting to replace gradient estimation, which enhances prediction accuracy. Comparative models including Support Vector Machine (SVM), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), Random Forest (RF), and Logistic Regression (LR) were introduced. Five performance evaluation metrics are utilized to assess the predictive capabilities of the CatBoost model. Based on CatBoost model, the predicted probability of slope instability is calculated, and the early warning model of slope instability is further established. The results suggest that the CatBoost model demonstrates a 6.25% disparity in accuracy between the training and testing sets, achieving a precision of 100% and an Area Under Curve (AUC) value of 0.95. This indicates a high level of predictive accuracy and robust ordering capabilities, effectively mitigating the problem of overfitting. The slope instability warning model offers reasonable classifications for warning levels, providing valuable insights for both research and practical applications in the prediction of slope stability and instability warning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the stability of slopes has been a focal point in the fields of geotechnical and geological engineering. Slopes constitute a fundamental geological environment for various human engineering activities. Numerous slopes are formed through railway, mining, road, and construction projects. Once these slopes become unstable, they can trigger significant geological disasters such as landslides, collapses, and mudflows, leading to substantial loss of life, property damage, and adverse impacts on socio-economic development1,2. By the end of 2020, there were 328,654 geological hazard points in China, with landslides, collapses, mudflows, and unstable slopes accounting for 96.16% of these hazard points3. Consequently, the developing a reliable and effective predictive warning model for slope instability holds significant theoretical and practical importance.

Scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted research of varying depths on the analysis and evaluation of slope stability. Traditional methods for analyzing slope stability include model testing, theoretical analysis, numerical calculation, and statistical analysis4. However, as dynamic open systems, slopes are influenced by numerous factors, many of which are random and variable. This leads to complex nonlinear relationships between these factors and slope stability, thereby imposing certain limitations on traditional analysis methods5. In recent years, with the development of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning methods have been widely applied to slope stability prediction6. These predictions primarily focus on classification and regression, making supervised learning models in machine learning the commonly adopted approach. Supervised learning models can be categorized into single models and ensemble models7.

Common single models include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Neural Networks (NN), and Logistic Regression (LR). The single model is straightforward to implement and does not demand excessive computational resources or time; however, it tends to overlook the inherent characteristics of the data during the calculation process, which may result in inaccurate predictive outcomes. Despite the strong generalization capabilities of SVM in handling high-dimensional data, it faces high computational complexity when dealing with large datasets and lacks sensitivity to data8,9. NN can manage complex nonlinear relationships but require a substantial volume of data samples and have challenges in explaining the computation process10,11. LR offers fast training speed and is well-suited for binary classification tasks, but it struggles with imbalanced data12,13. Decision Trees require minimal data cleaning and operate quickly, but they often result in lower stability and typically provide locally optimal solutions14,15.

Integrated models combine multiple single models to form a stronger predictive model, effectively reducing the prediction bias and variance of individual models, thereby achieving relatively optimal performance. Common ensemble models include eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost). Wu et al. compared XGBoost and RF algorithms to evaluate slope safety and stability, concluding that XGBoost was the best evaluation model16. Zhang and Zhang employed LGBM algorithm to study slope stability prediction, proposing a model that adeptly captures the complex nonlinear relationships between influencing factors and slope stability17. XGBoost provides feature importance evaluation, offering higher interpretability, but it involves complex parameter tuning and high memory consumption. LightGBM uses a histogram-based algorithm, which reduces time complexity and computational cost, but it is prone to overfitting and sensitive to noise and outliers.

In the realm of contemporary slope stability prediction research, traditional predictive methods generally exhibit limitations, including poor universality, extended time requirements, and suboptimal performance of prediction models. Compared to other algorithms, CatBoost offers higher accuracy and shorter training times than XGBoost, and it better addresses the overfitting issues present in LightGBM through enhanced operations. CatBoost demonstrates exceptional performance, robustness, and generalizability. It is user-friendly and more practical. The predictive capabilities of CatBoost have been initially applied in fields such as automation technology18, medical health19, energy and environment20, and transportation21. However, it is seldom employed in the field of geotechnical engineering and slope stability analysis22,23. CatBoost enriches feature dimensions and combats noise points in the training set. Compared to other models, it reduces the need for hyperparameter tuning and lowers the probability of overfitting, making it particularly suitable for applications in geological disaster prediction.

Based on aforementioned studies, it is proposed to use the slope instance data from24 to establish a slope prediction database. A slope stability prediction model will be established using CatBoost, and its performance will be compared with common machine learning models: SVM, LGBM, RF, and LR. The effectiveness of CatBoost model’s predictions will be validated through these comparisons. Subsequently, a slope instability early warning model will be developed based on this foundation, providing corresponding warning levels. This approach aims to offer new solutions for related research and practical applications.

CatBoost

CatBoost is an ensemble learning algorithm that builds on the enhanced Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) method, which was developed by Yandex in 2017 25. The algorithm utilizes a symmetric tree as its fundamental structure, employs a preprocessing method for feature splitting, and incorporates an ordered boosting strategy to mitigate gradient bias and prediction offset issues that are frequently encountered in gradient boosting algorithms. This leads to efficient classification with a high level of robustness.

GBDT

The fundamental procedure of CatBoost entails utilizing the gradient boosting algorithm to compute the loss function in the function space. The process involves iteratively combining weighted weak learners to minimize the loss function and achieve an optimal decision tree structure as shown in Fig. 126. The basic process is as follows27:

When provided with a training dataset \(T = \left\{ {(x_{1},y_{1}),(x_{2},y_{2}), \ldots ,(x_{N},y_{N})} \right\}\), a loss function \(L(y_{i},f(x))\), the slope can be determined. Initializing weak learners, the constant value that minimizes the loss function can be obtained as Eq. (1).

By iterating the training process for \(m = 1,2, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,M\) and calculating residuals for each sample \(i = 1,2, \ldots,N\). The residual \(r_{im}\), which is defined as the negative gradient of the loss function at the proposed model’s value, can be determined as Eq. (2).

Employing the residual \(r_{im}\) as the new ground truth for the sample, thereby making \((x_{i},r_{im})\) the input for the subsequent tree. \(f_{m}(x)\) represents the new tree, while \(R_{jm}(j = 1,2, \ldots ,J_{m})\) representing the corresponding leaf node region. The optimal fit value that minimizes the loss function for the leaf region can be determined using Eq. (3).

The final strong learner is represented as Eq. (4).

where \(I\) is the indicator function. If \(x \in R_{jm}\), \(I = 1\). Otherwise, \(I = 0\).

Symmetric tree

CatBoost employs a symmetric tree as the foundational model, wherein it encodes the index of each leaf node in a binary vector of the same length as the tree depth. This process guarantees uniformity in the division of features at every iteration, thereby preserving full symmetry and equilibrium between the left and right subtrees. This design reduces the complexity of the model, thereby improving the accuracy of slope stability prediction, training speed, and memory utilization. At each iteration, the leaves of the preceding tree are divided using identical conditions. Selecting the feature split that results in the lowest loss is of paramount importance. The balanced tree structure facilitates efficient CPU implementation, diminishes prediction time, and functions as a form of regularization to mitigate overfitting28.

Feature combination partition

CatBoost organizes and stores the 6 features of slope data by grouping them. However, an excessive number of feature combinations may lead to a substantial increase in the final model size. The storage capacity is contingent upon the quantity of values that each feature encompasses. By partitioning the decision tree model to reduce the final model size and taking into account the potential weights of features, the algorithm chooses the optimal partition29. The scoring formula for various partition scenarios30 is provided in Eq. (5).

where \(s_{new}\) is the new Score for the slope feature partition; \(s_{old}\) is the old Score for the feature partition; u is the number of features; U is the maximum value of u; and Z is the model size coefficient. Various partition scenarios are evaluated and compared based on their respective Scores, with the optimal scenario being selected.

Ordered boosting

While conventional gradient boosting algorithms involve fitting a new tree to the gradient of the proposed model, CatBoost introduces enhancements to address the problem of overfitting resulting from biased pointwise gradient estimates. The issue of overfitting, stemming from biased pointwise gradient estimation, has been observed in numerous models, rendering them susceptible to overfitting when applied to small and noisy datasets. To address this challenge and achieve unbiased gradient estimation, CatBoost initially trains a distinct model Mi for each sample xi, utilizing all samples except Mi. Subsequently, it employs the traditional GBDT framework31,32. The model Mi is utilized for estimating gradients of the samples, while the gradient training base learner is leveraged to derive the final model. CatBoost employs an ordered boosting strategy to replace the gradient estimation method used in traditional gradient-boosting algorithms. The algorithm establishes relatively independent models for different slope samples by incorporating prior terms and weight coefficients. It continuously trains base learners using gradient values, thereby reducing bias in gradient estimation and enhancing the model’s generalization capability33.

Establishment of the model

Slope stability database

A database was created by compiling 221 sets of slope instance data gathered from more than 60 locations, as depicted in Table 1. The dataset includes 115 stable slopes and 106 failure slopes. The stability of a slope is affected by various factors, including the slope’s geometry, geological characteristics, and the impact of surface and groundwater. These factors can be broadly categorized into three distinct categories: slope geometry, geotechnical physical parameters, and the presence of water within the geotechnical body. The majority of slope failure forms documented in the database display characteristics of near-circular sliding, which is a prevalent type of slope in engineering projects34. Key factors influencing the stability of these slopes, as demonstrated by various studies35,36,37, encompass slope height (H), slope angle (β), unit weight (γ), cohesion (C), internal friction angle (Φ), and pore pressure ratio (ru). Slope height and slope angle are utilized to characterize the fundamental geometry of a slope. The mechanical properties of rock and soil bodies are represented by unit weight, cohesion, and internal friction angle. Cohesion and internal friction angle are critical parameters that influence slope stability. The strength reduction method is applied through iterative adjustments of cohesion and internal friction angle. The pore pressure ratio is employed to describe the water content in rock and soil, defined as the ratio of pore water pressure to overlying rock pressure. Rainfall results in an increase in the pore water pressure ratio. The database was constructed based on 6 variables and the slope state.

Distribution characteristics

Several feature variables display variations in slopes. It is essential to comprehend the characteristics of slope features in various states for qualitative analysis. Figure 2 displays box plots and normal distribution curves for the 221 instances of the slope, with specific numerical values indicated. The calculation of skewness and kurtosis was performed in Table 2, and the analysis of each feature variable was conducted using a combination of "box plots + normal distribution curves." Skewness and kurtosis are frequently employed statistical measures that depict the asymmetry and peakedness of data distributions, serving as tools for evaluating the properties of probability distributions. In general, if the absolute values of the skewness and kurtosis coefficients are less than 1.96 times the standard error, it can be inferred that the data conforms to a normal distribution38.

The variable H exhibits a skewness of 1.942 and a kurtosis of 3.267, suggesting a departure from normal distribution. The values are predominantly clustered within the range of 40 m to 50 m, with a maximum value of 565 m and a minimum value of 3.66 m. The representation includes slopes of varying heights, such as low, medium–high, high, and ultra-high. In Fig. 2, the normal distribution curves for β and γ exhibit a relatively low kurtosis, with median values close to the mean, suggesting a uniform and symmetric distribution with minimal deviation. The 25th to 75th percentiles for slope angles are represented by values of 25° and 45°, suggesting the existence of steep, moderate, and gentle slopes. C exhibits a skewness of 4.156 and a kurtosis of 22.902, suggesting a departure from normal distribution. The skewness of Φ is characterized by a small and negative value, indicating a left-skewed distribution of most data points with large internal friction angle values. This is further emphasized by the relatively large absolute value of the skewness. The skewness for ru is greater than 0, while the kurtosis is less than 0, suggesting a right-skewed distribution with relatively small pore pressure ratios. An extensive evaluation considering the γ, C, and Φ indicates that the quantity of rocky slopes is limited to 15, constituting less than 10% of the slope dataset. Moreover, the instance data predominantly consists of soil slopes, with cohesive soil slopes accounting for over 95% of the total39.

In summary, the "box plots + normal distribution curves" illustrate the data distribution for each slope stability feature variable. Out of the 6 feature variables, only the variable γ conforms to a normal distribution. To conduct a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between the feature variables, it is necessary to normalize the data.

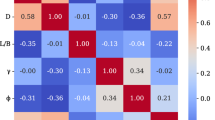

Correlation analysis

Due to the presence of outliers in the slope feature variables and their non-normal distribution, which could potentially affect predictive accuracy in subsequent stages, all variables were subjected to transformation using the Box-Cox method40. Following the transformation, all the data closely approximated a normal distribution, which allowed for further correlation analysis.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is a statistical measure used to assess the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables which was utilized to conduct a correlation analysis. The absolute values of the Pearson correlation coefficient fall within specific ranges to indicate the strength of correlation. A value between 0 and 0.2 suggests an extremely weak or no correlation, while a value between 0.2 and 0.4 indicates a weak correlation. A value between 0.4 and 0.6 suggests a moderate correlation and a value between 0.6 and 0.8 indicates a strong correlation. Finally, a value between 0.8 and 1 indicates an extremely strong correlation41. Figure 3 depicts the distribution and interrelationships of slope feature variables. The diagonal depicts the histograms of individual features, while the upper triangle presents the correlation coefficients between two slope features. The lower triangle illustrates the distribution density and linear fitting curves for the two features. The figure indicates that the absolute values of the correlation coefficients between the variable ru and other features, as well as between variables H and C, are all below 0.2. The data points in the lower triangle are distributed around the fitting curves, suggesting a very weak correlation between these variables. The highest correlation coefficient values are observed between γ and Φ, reaching a value of 0.46. The data points in the lower triangle exhibit a higher concentration around the fitting curve, indicating a moderate correlation between them.

In brief, the correlation coefficients between the features are all below 0.6, suggesting a weak correlation. The features exhibit a complex non-linear relationship, and all 6 slope features can be regarded as parameters for forecasting slope stability, demonstrating the model’s capacity to accommodate such intricate relationship data.

CatBoost slope stability prediction model

A set of 221 data points, comprising 6 variables (H, β, γ, C, Φ, and ru), was chosen as the input for the CatBoost slope stability prediction model. The input data underwent normalization using the min–max standardization method. Due to the limited sample size, the dataset was partitioned into a training set and a test set. After optimizing the traditional 6:2:2 ratio of training, validation, and test sets and comparing results with different ratios, the data was partitioned randomly into training and testing sets at an 8:2 ratio, followed by the implementation of fivefold cross-validation on the training set. The CatBoost algorithm iterated through the 6 slope features, splitting them to construct symmetric decision trees. The potential feature weights were taken into consideration, and the algorithm utilized an ordered boosting method to select the optimal partition. Different models were developed for various slope samples, with a continuous training process for base learners using gradient values. Ultimately, the optimal parameters were identified through grid search in conjunction with cross-validation, resulting in the development of a relatively optimal model that underwent validation using the testing set. To illustrate the predictive abilities of CatBoost, this study compared its performance with SVM, LGBM, RF, and LR models. In this process, the mesh search method integrated with cross-validation (GSCV) was employed to optimize the parameters of five models, thereby determining the optimal parameters for each model.To guarantee the reliability and applicability of the findings, five performance evaluation metrics were employed to evaluate the predictive capability of the model. The detailed process is depicted in Fig. 4.

Slope instability warning model

Previous studies have shown that the application of machine learning in geological disaster early warning research is limited, primarily focusing on earthquakes and ground surface deformation42,43. In contrast, slope instability issues face challenges due to difficulties in data measurement and constraints related to time and space, resulting in a predominance of qualitative analyses44. The CatBoost-based early warning system for slope instability can effectively predict such instabilities and accurately classify warning levels when provided with known data. This offers valuable support for early warnings and preventive measures in geotechnical engineering applications, including foundation pit construction and mining operations.

Upon the establishment of the CatBoost prediction model, probability values for both correct and incorrect predictions were obtained. The frequencies of stable and failure slopes with accurate predictions were tallied. The instability probability was computed for stable slopes with accurate predictions, and distribution intervals and frequencies were determined. This information was utilized in the development of a model for predicting slope instability, which involved the definition of various warning levels. Various levels of warnings were employed to facilitate assessment through manual examination and other techniques for identifying hazardous zones and implementing appropriate preventive measures as shown in Fig. 5.

Results and discussion

Comparative analysis

Model evaluation metrics

Machine learning algorithms necessitate distinct model evaluation standards for various problems. In this study, the prediction of slope stability classification was evaluated using 5 metrics: accuracy, precision, F1-Score, recall, and Area Under Curve (AUC). The confusion matrix, which is a standard format for evaluating precision, is a matrix with n rows and n columns, as depicted in Table 3.

Where TP represents the number of samples stable and predicted as stable; FP represents the number of samples failing but predicted as stable; FN represents the number of samples stable but predicted as failure; and TN represents the number of samples failing and predicted as failure. The most direct evaluation metric for classification problems is accuracy. Precision refers to the ratio of correctly predicted stable samples to the total samples predicted as stable by the model. In general, greater precision signifies a heightened capacity of the model to distinguish failure samples, leading to improved outcomes. The accuracy and accuracy ranges from 0 to 1, and the larger the value, the stronger the classification and prediction ability of the model. F1-Score can be conceptualized as the weighted average of precision and recall, with values ranging from 0 to 1. The model’s performance is better as it approaches a value of 1, and worse as it approaches 0. The recall is defined as the proportion of correctly identified stable samples to all stable samples, and its effectiveness aligns with the F1-Score. AUC denotes the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, typically falling within the range of 0.5 to 1. AUC represents a probability value, and a higher value signifies a model that is closer to perfection and demonstrates superior classification performance. The formulas for each metric and the coordinates of the ROC curve are provided as Eqs. (6)–(10) 16:

Comparative validation

To assess the effectiveness of the CatBoost prediction model, four other models (SVM, LGBM, RF, and LR) were compared with the CatBoost model in relation to accuracy, precision, recall, F1-Score, and AUC on both the training and testing sets.

Figure 6 depicts the precision of each model on both the training and testing sets. CatBoost and RF models both attained a training set accuracy of 99.43%, with LGBM following closely at 98.86%. SVM and LR models demonstrated lower training set accuracy, achieving 81.82% and 73.86%, respectively. While CatBoost and RF models exhibited similar classification abilities on the training set, they demonstrated various classification performances on the testing set. The CatBoost model achieved an accuracy of 93.18% on the testing set, representing a deviation of 6.25% from the training set. The accuracy of the RF model on the testing set was 86.36%, indicating a deviation of 13.07% from the accuracy observed in the training set. The models exhibited high accuracy when trained on the samples, but showed poor performance when tested, a phenomenon also noted in SVM, LGBM, and LR models. The disparities in accuracy between the training and testing sets for these 4 models all exceeded 10%, suggesting inadequate classification performance on the testing set and overfitting. Consequently, the CatBoost model demonstrated superior parameter selection capability in terms of accuracy on both the training and testing sets, in comparison to other models.

Figures 7 and 8 depict three-dimensional geometric shapes illustrating precision, recall, and F1-Score, as well as ROC curves for each model. The results suggest that the CatBoost model demonstrates superior performance across all performance metrics compared to other models, as indicated by specific values highlighted in the figures.

In Fig. 7, the distance of the CatBoost corresponding sphere from the origin is greater than that of the other 4 points. The precision projections of each model on the test set are represented as a square, while the recall projections are depicted as a circle, and F1-Score projections are illustrated as a triangle. CatBoost model exhibits a precision of 100%, surpassing that of the other 4 algorithms, effectively differentiating failure samples. The number of accurately predicted stable slope samples corresponds to the actual number of stable slope samples. The model’s predictive performance is better illustrated by the combination of precision and accuracy. Accuracy denotes the likelihood of accurately hitting the target, whereas precision refers to hitting a particular point within the target. The CatBoost model exhibits a recall rate of 85.71%, signifying the percentage of stable slope samples correctly predicted in the dataset, thereby showcasing the model’s strong classification capability for slope stability within the dataset categories. Among the 5 models, the CatBoost model demonstrates an F1-Score value of 61.02%, surpassing the F1-Score values of the remaining 4 models. F1-Score is affected by both precision and recall, as it represents their harmonic mean. When the values of precision and recall are closely aligned and high, F1-Score tends to be higher. However, when there is a significant difference between the two values, F1-Score tends to be closer to the lower of the two.

ROC curves for each model are depicted in the figure below. AUC values for CatBoost, SVM, LGBM, RF, and LR models are 0.95, 0.69, 0.89, 0.93, and 0.62, respectively. AUC is a widely utilized evaluation metric for binary classification models. A value approaching 1 signifies superior classification performance. CatBoost model demonstrates a higher AUC value compared to the other 4 models, indicating its strong ability to sort slope sample data. In conclusion, the CatBoost model exhibits significantly superior slope stability prediction capabilities compared to other models and possesses effective sample sorting capabilities.

Warning level division

Among the 221 slope instance data, 44 sets of data were utilized as a test set to validate the CatBoost model. The test set achieved an accuracy of 93.18%, with 41 sets predicted correctly and 3 sets predicted incorrectly. The prediction of the CatBoost model is determined by comparing the predicted probability of stability with a threshold of 0.5. If the anticipated likelihood of stability exceeds 0.5, the outcome of the prediction indicates a stable slope; otherwise, it suggests instability. Following statistical analysis of the prediction outcomes, 23 stable slopes were correctly predicted, while 18 slopes were classified as failures.

Figure 9 illustrates the line graph of the probability distribution for accurately predicted slopes and accurately predicted stable slopes. The two lines have little difference in distribution frequency and similar distribution trend in each interval, with the purple line indicating accurately predicted slopes. The frequency of distribution for predicted probabilities less than 0.9 does not surpass 0.25. The green line depicts stable slopes that have been accurately predicted, with a distribution frequency that does not exceed 0.1 for predicted probabilities less than 0.9. CatBoost model demonstrates a high level of precision and stability in predicting slope instability.

The 23 stable slopes that were accurately predicted are categorized into 5 intervals based on their predicted probabilities: 0.5–0.6, 0.6–0.7, 0.7–0.8, 0.8–0.9, and 0.9–1.0. The distribution frequencies corresponding to the values are 0, 0.043, 0, 0.043, and 0.91, respectively. In the study by He et al.45 on the development of a remote monitoring and early warning system for landslide geological disasters, a 4-level early warning system was established. This system includes stable, sub-stable, near-sliding, and imminent sliding warnings. CatBoost model accurately predicted 23 stable slopes, in accordance with their frequency distribution and relevant warning regulations46, the slope instability early warning system is categorized into 3 levels. When the anticipated probability of slope instability falls below 0.1, the slope is considered to be in a stable warning state, indicated by the color blue. When the anticipated likelihood of slope instability falls within the range of 0.1 to 0.3, the slope is considered to be in a condition of sub-stable warning, denoted by the color yellow. When the anticipated likelihood of slope instability falls within the range of 0.3 to 0.5, the slope is considered to be in a state of imminent sliding, denoted by the color red. The precise categorization is presented in Table 4.

The frequency distribution of predicted slope probabilities exceeding 0.9 is 0.91, accompanied by a significant test accuracy of 93.18%. The results suggest that the CatBoost model exhibits robust classification capabilities in predicting the stable state of slopes, albeit with a certain degree of inaccuracy. The warning model is only appropriate for accurately predicting stable slopes. Upon application, the CatBoost slope stability prediction model exhibits a high level of accuracy in providing early warnings for slope instability.

Limitations

The comparative analysis above indicates that the predictive performance of the slope stability model based on CatBoost is significantly superior to other models. The early warning model established on this basis demonstrates certain applicability, but there are still some limitations in this study that can be addressed in future research.

Firstly, this study only considered slope failures dominated by circular sliding failure, and did not consider other types of slope failures. In the process of establishing the database and the final slope instability warning model, no consideration was given to rainfall, earthquakes, and human activities, because the collection of slope parameter data of various types is difficult. Therefore, in future research, it may be possible to consider as many slope types and characteristic variables as possible to further improve the model’s universality. Secondly, this study did not calculate the slope stability coefficient, but simply divided the slope stability into stable and unstable states and established a binary classification prediction model. In the future, the slope stability coefficient can be classified into intervals for better prediction of the slope stability state. Thirdly, the early warning model lacks big data support, and multi-party data training can be collected to improve its robustness.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from the experimental results:

-

1.

The CatBoost stability prediction model that was developed demonstrates effective prediction of slope stability, achieving a test accuracy of 93.18%. Additionally, the precision, recall, F1-Score, and AUC metrics reached 100%, 85.71%, 61.02%, and 0.95, respectively. CatBoost model demonstrates high accuracy, robust classification performance, and the capability to address gradient bias and prediction offset issues when applied to slope stability prediction problems.

-

2.

In comparison to SVM, LGBM, RF, and LR models, the CatBoost model demonstrates an improvement in accuracy ranging from 6.82% to 29.54%, precision from 10.53% to 38.1%, recall from 4.76% to 23.81%, and F1-Score from 1.37% to 9.96%. The findings suggest that the CatBoost model effectively mitigates challenges related to low test accuracy resulting from overfitting, and exhibits a degree of superiority, thereby offering valuable contributions to the field of slope stability prediction research.

-

3.

An instability early warning model is established by obtaining the predicted probability of instability for correctly predicted stable slopes. The warning system is categorized into three levels according to probability values: stable, sub-stable, and near-sliding warnings. This classification offers guidance for early warning and prevention efforts related to slope instability.

-

4.

The accuracy and precision of the slope stability prediction model based on CatBoost are notably high. Furthermore, the early warning model demonstrates a significant accuracy rate with stable distribution. This further indicates that the CatBoost model effectively characterizes the dynamics of slope instability changes. Consequently, it can be practically applied to various slope and embankment projects, including foundation pit support, open-pit excavation, and geotechnical reinforcement. Thus, it provides a scientific reference for geotechnical engineering.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dai, Z. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on the mechanism of ground collapse induced by underground drainage pipe leakage. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-11344-w (2024).

Deng, L. C. et al. Forecasting and early warning of shield tunnelling-induced ground collapse in rock-soil interface mixed ground using multivariate data fusion and Catastrophe Theory. Eng. Geol. 335, 0013–7952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2024.107548 (2024).

China Ministry of Natural Resources, Beijing, China. National Geological Disaster Prevention and Control "14th Five-Year Plan". https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-01/04/content_5734957.htm (2022).

Cao, N. et al. Slope stability analysis based on KPCA-IA-SVM. Foreign Electron. Meas. Technol. 42(06), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.19652/j.cnki.femt.2304812 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Slope stability analysis model based on PSO-RVM. Sci. Technol. Eng. 23(19), 8370–8376. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2023.19.039 (2023).

Wang, S., Zhang, Z. & Wang, C. Prediction of stability coefficient of open-pit mine slope based on artificial intelligence deep learning algorithm. Sci. Rep. 13, 12017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38896-y (2023).

Lu, W. Machine Learning Formula Derivation and Code Implementation Vol. 505 (Posts and Telecommunications Press, 2022).

Wang, G. J. et al. Intelligent prediction of slope stability based on visual exploratory data analysis of 77 in situ cases. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33(01), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-2686.2023.01.003 (2023).

Masurkar, A. et al. Performance analysis of SAR filtering techniques using SVM and Wishart Classifier. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 34, 2352–9385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2024.101189 (2024).

Guo, Z. et al. Stability prediction of basalt residual soil highway slope based on residual thrust method and back propagation artificial neural. Highway 62(01), 19–26. (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. A new DEM calibration method for wet and stick materials based on the BP neural network. Powder Technol. 448, 0032–5910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2024.120228 (2024).

Bhagat, N. K. et al. Application of logistic regression, CART and random forest techniques in prediction of blast-induced slope failure during reconstruction of railway rock-cut slopes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 137, 106230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106230 (2022).

Zhong, H. et al. A study of road closure due to rainfall and flood zone based on logistic regression. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 102, 2212–4209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104291 (2024).

Hu, J., Qi, C. M., Sun, B. & Nie, C. L. Research on slope stability evaluation based on C4.5 decision tree algorithm. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 32(12), 82–86 (2015).

Arifuddin, A. et al. Performance comparison of decision tree and support vector machine algorithms for heart failure prediction. Proced. Comput. Sci. 234, 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.03.048 (2024).

Wu, M. T., Chen, Q. S. & Qi, C. C. Slope safety, stability evaluation and protective measures based on machine learning. Chin. J. Eng. 44(02), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn2095-9389.2021.06.02.008 (2022).

Zhang, K. & Zhang, K. Prediction study on slope stability based on LightGBM algorithm. China Saf. Sci. J. 32(07), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2022.07.1473 (2022).

Joo, C. et al. Machine learning-based heat deflection temperature prediction and effect analysis in polypropylene composites using catboost and shapley additive explanations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 126(PA), 106873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106873 (2023).

Wang, J., Wang, P. C., Guo, Q. & Yuan, B. X. Risk prediction of hyperlipidemia in the elderly based on machine learning. Mod. Prev. Med. 50(18), 3408–3413. https://doi.org/10.20043/j.cnki.MPM.202303660 (2023).

Wu, C. et al. Reconstructing annual XCO2 at a 1 km× 1 km spatial resolution across China from 2012 to 2019 based on a spatial CatBoost method. Environ. Res. 236, 116866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116866 (2023).

Bo, Y., Liu, Q., Huang, X. & Pan, Y. Real-time hard-rock tunnel prediction model for rock mass classification using CatBoost integrated with Sequential Model-Based Optimization. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 124, 104448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104448 (2022).

Noaman, M. F. et al. Geotechnical and microstructural analysis of high-volume fly ash stabilized clayey soil and machine learning application. Case Studi. Constr. Mater. 21, 2214–5095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03628 (2024).

Chou, J. S. et al. Metaheuristic optimization within machine learning-based classification system for early warnings related to geotechnical problems. Autom. Constr. 68, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2016.03.015 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. Slope stability prediction for circular mode failure using gradient boosting machine approach based on an updated database of case histories. Saf. Sci. 118, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.05.046 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. A rock mass strength prediction method integrating wave velocity and operational parameters based on the bayesian optimization Catboost algorithm. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27, 3148–3162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-023-2475-9 (2023).

Zhang, T., Huang, Y., Liao, H. & Liang, Y. A hybrid electric vehicle load classification and forecasting approach based on GBDT algorithm and temporal convolutional network. Appl. Energ. 351, 121768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121768 (2023).

Yang, J., Zhao, C., Yu, H. & Chen, H. Use GBDT to predict the stock market. Procedia Comput. Sci. 174, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.06.071 (2020).

Jin, C. et al. CatBoost-based arc fault identification method for common electrical load. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 60(07), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.19753/j.issn1001-1390.2023.07.028 (2023).

He, J. Z., Feng, X. D. & Liu, T. Q. Sand liquefaction prediction by using CatBoost algorithm combined with optuna framework. J. Univ. Jinan Sci. and Technol. https://doi.org/10.13349/j.cnki.jdxbn.20230913.001 (2023).

Prokhorenkova, L. et al. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. https://doi.org/10.5555/3327757.3327770 (2018).

Chai, J. et al. CatBoost mine pressure appearance prediction based on bayesian algorithm optimization. Ind. Min. Autom. 49(07), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.13272/j.issn.1671-251x.2022110065 (2023).

Zeng, S. Y., Xie, T. & Kong, R. Y. Water depth inversion based on CatBoost and XGBoost combination model. Hydrogr. Surv. Charting 43(03), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-3044.2023.03.013 (2023).

Liu, A. Q., Guo, S. P. & Zhang, Z. X. Design and implementation of text auto-classification system based on LDA model fusion Catboost algorithm. J. Natl. Libr. China 32(05), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.13666/j.cnki.jnlc.2023.0508 (2023).

Hoang, N. D. & Pham, A. D. Hybrid artificial intelligence approach based on metaheuristic and machine learning for slope stability assessment: A multinational data analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 46, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2015.10.020 (2016).

Liang, Y., Wu, B. & Li, J. Analysis of slope stability of multi-slide belt parallel layer rock slopes based on energy balance method. Highway 68(10), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.13666/j.cnki.jnlc.2023.0508 (2023).

Geng, Y.J. et al. Research on gra-topsis evaluation model for slope stability of open pit mines based on variable weight theory. Nonferrous Met. Sci. Eng. 1–10. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/36.1311.tf.20230918.1041.002.html (2023).

Yao, Y. & Wang, X. M. Slope stability analysis model based on PCA-ERBF-SVM. J. Catastr. 37(03), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-811X.2022.03 (2022).

Ji, C. X. et al. Normal distribution test and space-time characteristics of precipitation in Shenyang of Liaoning Province. J. Arid. Meteorol. 36(06), 954–962+989. https://doi.org/10.11755/j.issn.1006-7639(2018)-06-0954 (2018).

Sun, X. D. & Wang, D. Analysis of soil cohesion value. LiaoNing Build. Mater. 03, 39–41. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-0142.2010.03.025 (2010).

Jin, A. B., Zhang, J. H., Sun, H. & Wang, B. X. Intelligent prediction and alert model of slope instability based on SSA-SVM. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 50(11), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.13245/j.hust.221118 (2022).

Kong, F. et al. PSO-based machine learning methods for predicting ground surface displacement induced by shallow underground excavation method. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27(11), 4948–4961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-023-0121-1 (2023).

Song, J. D. et al. In-situ alarm level earthquake early warning experiment based on machine learning prediction model: A case study of the Luding magnitude 6.8 earthquake on September 5, 2022 in Sichuan Province. Chin. J. Geophys. 67(08), 3004–3016. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg.2022Q0789 (2024).

Li, H. Z. et al. Early warning of surface deformation risk during construction of shallow-buried subway stations. J. Shandong Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 53(06), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.6040/j.issn.1672-3961.0.2022.295 (2023).

Huang, L. Research on meteorological early warning model of landslide disaster in Wenchuan earthquake area based on machine learning. J. Geod. Geoinf. Sci. 49(02), 267. https://doi.org/10.11947/j.AGCS.2020.20190061 (2020).

He, M. C., Ren, S. L. & Tao, Z. G. Remote monitoring and forecasting system of newton force for landslide geological hazards and its engineering applications. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 40(11), 2161–2172. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2020.1189 (2021).

China Meteorological Administration. Measures for Issuing and disseminating Early Warning Signals of Meteorological Disasters. https://www.cma.gov.cn/zfxxgk/gknr/flfgbz/gz/202005/t20200528_1694399.html (2007).

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Team Project of Hebei GEO University (KJCXTD-2021-08) and the Central Government guided local Science and Technology development Fund Project (Basic research of Free exploration type) (246Z5405G), which is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. wrote the main manuscript text; Y.Y. and A.Z. put forward the whole idea of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Yuan, Y. & Zhou, A. Predictive slope stability early warning model based on CatBoost. Sci Rep 14, 25727 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77058-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77058-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Constructing a machine learning model for predicting early postoperative recurrence of pancreatic head cancer based on a novel inflammatory factor composite index

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Predicting CaO activity in multiple slag system using improved whale optimization algorithm and categorical boosting

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Machine learning-based identification of key factors and spatial heterogeneity analysis of urban flooding: a case study of the central urban area of Ordos

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Random forest-based prediction of shallow slope stability considering spatiotemporal variations in unsaturated soil moisture

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Research on subway settlement prediction based on the WTD-PSR combination and GSM-SVR model

Scientific Reports (2025)