Abstract

Active faults along railways in the mountainous regions of western China pose significant challenges to bridge safety. To ensure the safe operation of long-span railway bridges under complex geological conditions, this study investigates the synthesis of artificial ground motions for bridges crossing strike-slip faults and analyzes their nonlinear seismic response. First, we develop a theoretical method for simulating high- and low-frequency seismic motions using a finite fault and an equivalent velocity pulse model. Next, using a specific long-span railway cable-stayed bridge as a case study, we construct a nonlinear finite element model with OpenSees software. Finally, we assess the seismic response of key bridge components considering various crossing angles, seismic amplitudes, fault rupture directivity, and fling-step effects. The results show that the crossing angle significantly influences the seismic response, with longitudinal and transverse responses exhibiting opposite patterns. Additionally, the scaling factor of seismic motion significantly affects bridge response. For bridges crossing strike-slip faults, the longitudinal response exhibits a sudden increase in displacement due to instantaneous velocity pulses, while the transverse response shows notable residual displacement influenced by the fling-step effect. However, the critical section curvatures of bridge towers and piers remain within the elastic range across all crossing angles, indicating that controlling large displacement deformations is crucial for the seismic design of bridges crossing strike-slip faults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid global development of bridge engineering has led to an increase in bridge construction in high-intensity mountainous areas. Consequently, seismic research on bridges near or crossing active faults has gained significant attention from earthquake engineers. Earthquakes have a particularly severe impact on bridge structures spanning surface fracture zones compared to other regions.Notable examples include the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, the 1999 Kocaeli earthquake, the Düzce earthquake in Türkiye, and the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, where over 20 bridges spanning or adjacent to fault lines collapsed, resulting in substantial economic losses and immense challenges for post-earthquake emergency rescue operations1,2,3,4,5.

The Railway from Ya’an to Linzhi, currently under construction, connects the Ya’an Station of the Cheng-ya Railway to Linzhi Station of the Tibet-Linzhi Railway, spanning 995.92 km. This section includes 146.88 km of new bridges, accounting for 14.75% of the total line length and comprising 98 bridges6. The region exhibits high levels of tectonic activity, featuring 17 significant active fault zones along the line and neighboring areas, along with over 100 fault zones that may impact engineering structures7. Considering constraints such as topography, road planning, project cost, construction period, and regional economic development, building bridges on active faults has become an unavoidable challenge in engineering construction8.

Park et al.9 and Ucak et al.10 analyzed the nonlinear response of the Bolu Viaduct under near-fault pulse effects using a high-low frequency superposition method. Their findings indicate that fault-crossing bridges must withstand additional static and dynamic displacement demands. Goel et al.11,12 developed a simplified method for evaluating the seismic response of traditional small to medium-span straight and curved bridges crossing faults. Saiidi et al.13 analyzed the support conditions of a three-span bridge under fault directivity effects through shake table experiments, finding that the span closest to the fault experienced the most severe damage, which decreased with increasing distance. Yi et al.14 focused on the seismic response of simply supported bridges crossing faults using multi-point excitation time history analysis. Hui et al.15,16,17 systematically studied the seismic performance of fault-crossing bridges, considering seismic damage, ground motion input, analysis models, and seismic response. Wang et al.18 assessed the response of an eight-span railway simply supported beam bridge crossing a strike-slip fault under graded seismic action. Jia et al. and Zeng et al.19,20 investigated the sensitivity of long-span suspension bridges to fault crossing angle, fault crossing position, permanent displacement, dynamic pulse motion, seismic components, and traveling wave effects. Their research shows that bridge response significantly increases when the fault crossing angle is 90°. Lin et al.21 found that fault displacement minimally impacts the acceleration response of the main towers of a twin-tower cable-stayed bridge crossing a dip-slip fault, but significantly affects the absolute displacement of the main tower and girder. Yang et al.5 and Jia et al.22 provided comprehensive reviews of the current research status on the seismic design of fault-crossing bridges.

For small to medium-sized fault-crossing bridges, researchers mainly focus on pier damage, bearing deformation, and displacement risk. In contrast, for long-span bridges, attention is centered on parameters such as fault crossing angle, fault location, and permanent ground displacement. This distinction arises because long-span bridges have greater spanning capability and are more susceptible to fault-crossing effects, while small to medium-sized bridges are less affected due to their shorter spans. Additionally, small to medium-sized bridges are generally easier to repair post-earthquake, emphasizing the importance of studying fault-crossing effects on long-span bridges.

Furthermore, there is a significant difference in the natural periods of small to medium-sized bridges compared to long-span bridges. Long-span bridges are typically flexible structures with longer periods, making them more likely to resonate under near-fault earthquakes, which usually have frequencies below 1 Hz. Therefore, studying the effects of fault-crossing on long-span bridges is of great significance.

Currently, the seismic design of bridges in the near-field area of trans-faults primarily relies on recorded natural seismic waves from foreign sources. However, these recordings are limited in number and do not accurately reflect the geological conditions in mountainous areas. Theoretical methods for seismic performance and engineering design of bridges in near-field cross-fault areas are also underdeveloped and require immediate attention. Near-field motion across faults exhibits significant directional effects, slip effects, vertical effects, and uplift effects. Fault-generated near-field velocity pulse ground motion possesses distinct characteristics such as similar velocity pulse waveforms, abundant medium and long cycle components, and prolonged pulse periods. Additionally, the peak velocity to acceleration peak ratio (PGV/PGA) is large, and ground motions may lead to permanent ground displacement. Consequently, seismologists have been studying the artificial synthesis of near-ground motion since the 1960s.

Hartzell23 proposed dividing the fault rupture surface into several sub-faults of a certain size and using each sub-fault as a point source in the empirical Green’s function method. Building on this idea, Boore24 introduced the renowned theory of random point source simulated ground motion. In 1990, Silva et al.25 put forth a finite fault model, laying the foundation for synthesizing fault near-site motions. In 1997, Beresnev and Atkinson26,27,28 developed a stochastic finite fault method that incorporates fault geometry information, combining it with the stochastic point source method to create the Fortran program FINSIM(a name for a FORTRAN program based on finite fault stochastic acceleration time histories) for finite fault simulations. While Beresnev and Atkinson’s stochastic finite fault simulations are ideal for near-field cases, the selection of sub-faults greatly affects the real simulation results, particularly for small and medium-sized earthquakes with relatively small fault sizes, thereby limiting the application scope of this approach. In 2012, Assatourians and Atkinson28 further modified and improved the FORTRAN procedure for the stochastic finite fault method.

Compared to conventional far-field motion excitation, bridge structures experience more complex dynamic responses, greater seismic demand, and more severe damage when subjected to strike-slip fault ground motion. With the commencement of construction projects like the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, which involve super structures, an increasing number of bridges face the risk of crossing potential faults. Thus, urgent research is needed in this area.

This paper focuses on a long-span railway cable-stayed bridge crossing an active fault. A finite element model for the bridge is developed using OpenSees software (Version 3.6.0, https://opensees.berkeley.edu). By implementing the equivalent velocity pulse model proposed by Makris et al.29, a low-frequency program is written in MATLAB (Version 2019R1) to simulate the rupture directivity effect perpendicular to the fault and the rupture directivity effect parallel to the fault direction within the low-frequency time-course component. The FORTRAN program (Version 90) for the finite fault simulation method is used to simulate the high-frequency time-history components. The high-frequency and low-frequency time-history components are combined using MATLAB (Version 2019R1), generating synthetic ground motion time history. The simulated ground motions are inputted into the finite element bridge model established with OpenSees (Version 3.6.0). Displacement, shear force, and bending moment response data from the bridge tower, pier, and main girder are extracted and extensively analyzed to investigate the influence of different fault locations, fault spanning angles, and permanent fault displacement on the seismic response of the structure.

Tp | Pulse period |

Vd | Directivity effect pulse amplitude |

Vf | Fling effect pulse amplitude |

Mw | Earthquake magnitude |

R | Fault distance |

DL | Permanent ground displacement |

NL | Along fault strike |

NW | Number of subfaults along the strike |

\(\Delta {t_i}_{j}\) | Time delay |

\({a_{ij}}(t)\) | Subsource acceleration |

\(\beta\) | Shear wave velocity at the source |

Me | Seismic moment of the subfault |

fe | Corner frequency |

\(E({M_0},f)\) | Source function |

\(P(R,f)\) | Path function |

G(f) | Site function |

I(f) | Ground motion type |

\({R_{\theta \varphi }}\) | Radiation pattern coefficient |

FS | Free surface amplification factor |

PRTITN | Horizontal component coefficient |

\(\rho\) | Density of the medium at the source |

\({M_0}\) | Seismic moment |

A(f) | Site amplification effect |

D(f) | Site attenuation effect |

\({Z_{\text{s}}}\) | Impedance near the source |

\({\rho _s}\) | Density at the source |

\({\beta _s}\) | Shear wave velocity at the source |

\(\bar {Z}(s)\) | Average surface impedance |

\(\bar {\rho }\) | Equivalent density of soil layers |

\(\bar {\beta }\) | Equivalent shear wave velocity of soil layers |

k | High-frequency attenuation parameter (kappa) |

ed | Fault slip direction coefficient |

Hybrid ground motion simulation of strike-slip faults

The scarcity of natural seismic wave records from near-field trans-fault events, coupled with significant disparities in site conditions between recorded seismic waves and actual bridge sites, poses substantial challenges for accurately calculating and analyzing strike-slip fault pulsed ground motions. Consequently, it is essential to develop an artificial simulation method for ground motions associated with strike-slip faults that can be widely applied and further researched. Considering the pronounced differences between high and low-frequency seismic waves in cross-fault ground motion, this study employs a hybrid simulation method to accurately replicate the time history of ground motion for fault-crossing bridges.

Simulation of the low-frequency time- history components

Simulation of the rupture directivity effect

The equivalent velocity pulse model is extensively used in low-frequency component simulations due to the presence of noticeable long-period pulses in near-fault seismic waves. The acceleration, velocity, and displacement of the equivalent pulse model for the directional effect of rupture perpendicular to the fault are represented by Eq. (1). In simulating the rupture directivity effect, the peak velocity in the velocity time history serves as the control parameter. The velocity time histories are determined first, followed by the derivation of acceleration and displacement time histories through integration and differentiation, respectively29.

Where Tp and Vd are the periods and amplitudes of the directional velocity pulses, respectively. Tp can be obtained from the statistical formula of pulse period and magnitude Mw perpendicular to the fault direction, and Vd can be calculated by the statistical formula of pulse peak perpendicular to the fault direction and magnitude Mw and fault distance R.

Simulation of the fling-step effect

The equations for acceleration, velocity, and displacement of a slip-like equivalent impulse model aligned with the fault direction are represented by Eq. (2). In the simulation, the permanent ground displacement DL in the displacement time history is used as the control parameter. Initially, the displacement time history is determined, followed by obtaining the velocity time history and acceleration time history through differentiation.

When t>Tp, add the following:

Where\({T_p}\)and \({V_f}\) is the period and amplitude of the fling-step effect velocity pulse, respectively. DL is the permanent displacement of the ground. \({T_p}\)can be obtained from the statistical formula of the pulse period and magnitude Mw parallel to the direction of the fault.

Simulation of the high-frequency time-history components

In the high-frequency simulation, the stochastic finite tomography simulation method is used to divide the fault into a series of sub-sources, each sub-source is regarded as a point source, the seismic wave propagates from the epicenter to the surroundings at a certain rupture velocity. When the seismic wave reaches the center of the sub-source, the sub-source is excited, the ground motion of all sub-sources at the observation point can be superimposed according to different delays to obtain the final ground motion time course.

-

1.

Stochastic finite tomography: The ground motions\(a({\text{t)}}\) received by the observation points are superimposed by the ground motions of each sub-source \({a_{ij}}(t)\)according to an appropriate time delay30:

$$a({\text{t)=}}\sum\nolimits_{{i=1}}^{{{N_L}}} {\sum\nolimits_{{{\text{j}}=1}}^{{{N_W}}} {{a_{ij}}} } (t+\Delta {t_i}_{j})$$(4)Where\({N_L}\)and\({N_W}\)is the number of sub-faults along strike and trend of faults, respectively; \(\Delta {t_i}_{j}\) is the corresponding time delay from the sub-source in row \(\:i\), column \(\:j\), to the observation, \({a_i}_{j}(t)\) is the sub-source acceleration in row \(\:i\), column \(\:j\),

\({a_i}_{j}(t)\) can be characterized by Eq. (5)31:

$${a_{ij}}(t) = \frac{{C{M_e}{{\left( {2\pi f} \right)}^2}}}{{1 + {{\left( {f/{f_e}} \right)}^2}}}\exp ( - \pi fk)\exp \left( {\frac{{ - \pi f{R_{ij}}}}{{Q\beta }}} \right)\frac{1}{{R_{ij}^b}}$$(5)Where \(\beta\) is the shear wave velocity of the medium at the seismic origin, unit\(km/s\);\({M_e}\) is the seismic moment of the sub-fault in row \(\:i\), column \(\:j\); \({f_e}\) is the corner frequency; \(\exp (\frac{{ - \pi f{R_{ij}}}}{{Q\beta }})\) is a hysteresis elastic attenuation function; \(\frac{1}{{R_{{ij}}^{b}}}\) is a geometry extension.

-

2.

Random point source simulation method:

Firstly, different models and corresponding parameters are selected to calculate the amplitude spectrum of ground motion by Eq. (6), The phase spectrum is randomly generated from Gaussian white noise. The simulated ground motion time history is obtained by performing inverse Fourier transformations on the amplitude spectrum and the phase spectrum24:

$$Y({M_0},R,f) =E({M_0},f) \times P(R,f) \times G(f) \times I(f)$$(6)Where\(E({M_0},f)\) represents the hypocenter, \(P(R,f)\) represents the path, \(G(f)\) represents the site, and \(I(f)\) represents the type of ground motion.

-

1.

Epicenter——Areas created by rupture deep in the earth’s crust, which is denoted by (7) in the stochastic simulation method:

$$E({M_0},f)=\frac{{{R_{\theta \varphi }} \times FS \times PRTITN}}{{4\pi \times \rho \times {\beta ^3}}} \times {M_0} \times S({f_c},f)$$(7)Where \({R_{\theta \varphi }}\) is the radiation pattern coefficient, which is generally considered to be a constant, and is often taken as 0.55. \(FS\) is a free surface magnification factor, which is usually 2.0; \(PRTITN\) is the horizontal component factor, which is usually 0.707; \(\rho\) is the density of the medium at the source, units \(g/c{m^3}\); \(\beta\)is the shear wave velocity of the medium at the source, units \(km/s\); \({M_0}\)is the seismic moment, the relationship between seismic moment and magnitude can be expressed by the following equation31:

$${M_W}=\frac{2}{3}{\log _{{M_0}}} - 10.7$$(8)\(S({f_c},f)\)is the shape function of the source spectrum, which can be expressed as follows:

$$S({f_c},f)=\frac{1}{{1+( {\text{f/}}{{\text{f}}_c}{)^2}}}$$(9)\({f_c}\) is the corner frequency, which can be expressed as32,33,34:

$${f_c} = 4.9 \times {10^6}\beta {\left( {\frac{{\Delta \sigma }}{{{M_0}}}} \right)^{\frac{1}{3}}}$$(10)Where \(\Delta \sigma\) is the stress drop, which is usually 4Mpa; the general value range of shear wave velocity \(\beta\) is 3.6 km/s ~ 3.8 km/s; the density is generally 2.7 g/cm3 or 2.8 g/cm3; the rupture velocity of the source is 0.8 times the shear wave velocity.

-

2.

Propagation path—After an earthquake occurs, the seismic waves generated from the hypocenter propagate to the surrounding areas, and the propagation path is the part of the medium in which seismic waves propagate inside the earth’s crust. The change of seismic waves through the propagation medium is often referred to as the path effect, which consists of two parts: geometric diffusion and hysteresis attenuation:

$$P(R,f)=G(R) \times {A_n}(f)$$(11)Where \(G(R)\)is Geometric diffusion;\({A_n}(f)\) is the hysteresis elastic attenuation.

\(G(R)\) also known as geometric attenuation, it refers to the fact that part of the energy of the seismic wave will be absorbed when it propagates in the medium, and the seismic wave will continue to decay with the increase of distance35:

$$G(R)=\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {\frac{1}{R}{\text{ }}R<70Km} \\ {\frac{1}{{70}}{\text{ }}70Km \leqslant R \leqslant 130Km} \\ {\frac{1}{{70}}\sqrt {\frac{{130}}{R}} {\text{ }}R \geqslant 130Km} \end{array}} \right.$$(12)Hysteresis attenuation represents the change of the frequency components of a seismic wave through the propagation medium.

$${A_n}(f)={e^{\frac{{\pi fR}}{{Q(f)\beta }}}}$$(13)Where f is frequency, units Hz; R is Epicenter distance, units km; \(\beta\) is shear wave velocity, units km/s; Q(f) is a quality factor, dimensionless, which reflects the energy of the propagation medium to the seismic wave.

$$Q(f)={Q_0}{f^n}$$(14)Where Q0 and exponent n are constants and both are dimensionless values.

-

3.

Site——A medium within a certain depth below the earth’s surface. Site impact consists of two parts: amplification effect and attenuation of the site:

$$G(f)=A(f) \times D(f)$$(15)Where \(A(f)\)is the amplification effect of the site, \(D(f)\)is attenuation effect for the site.

$$A(f)=\sqrt {\frac{{{Z_{\text{s}}}}}{{\bar {Z}(f)}}}$$(16)Where \({Z_{\text{s}}}\) is the wave impedance near the hypocenter.

$${Z_s}={\rho _s} \times {\beta _s}$$(17)Where \({\rho _s}\) is density at the hypocenter;\({\beta _s}\) is the shear wave velocity at the source; \(\bar {Z}(f)\) is the average wave impedance of the surface.

$$\bar {Z}(f)=\bar {\rho } \times \bar {\beta }$$(18)Where \(\bar {\rho }\)is the equivalent density of the soil layer, \(\bar {\beta }\) is the equivalent shear wave velocity of the soil layer.

$$D\left( f \right)={[1+{(\frac{f}{{{f_{\hbox{max} }}}})^8}]^{ - 0.5}}$$(19)Where \(\:{f}_{max}\) is the cut-off frequency. \(D\left( f \right)={e^{ - \pi kf}}\)

Where k is the high-frequency attenuation parameters kappa, which is usually 0.04s.

-

4.

Types of ground motion

$$I\left( f \right)={\left( {2\pi fi} \right)^n}$$(20)$${\text{Where}}\;i=\sqrt { - 1} ,\;n=\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {0\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {}&{} \end{array}}&{Displacement} \end{array}} \\ {1\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {}&{} \end{array}}&{} \end{array}}&{}&{Velocity} \end{array}} \\ {2\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {}&{\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {}&{} \end{array}Acceleration} \end{array}} \end{array}} \right.$$(21)

Hybrid ground motion simulation of strike-slip faults

The hybrid simulation method (HSM) integrates both high and low-frequency components of near-field seismic waves, the flow chart of HSM has shown in Fig. 1. The acceleration, velocity, and displacement time histories of the high-frequency component are calculated using preset parameters such as earthquake magnitude (Mw), epicenter distance, and fault distance through Fortran programming to reflect the specific site conditions at the bridge site. The low-frequency component is derived using pulse characteristic parameters and an existing equivalent velocity pulse model, accounting for forward directivity and slip effects. By ensuring equal total durations and load sub-step times for both high and low-frequency components, the displacement time history of cross-fault ground motion is obtained through superposition across the entire time domain.

Nonlinear finite element model of the railway long-span cable-stayed bridge

Project overview

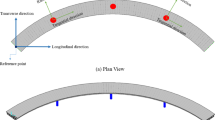

This paper examines a cable-stayed bridge with a span configuration of (51 + 91 + 300 + 91 + 51) meters, forming a semi-floating system. The ratio of the side span to the main span is 0.473, and the total length of the bridge, including the end joints, is 584 m. The main bridge is positioned on a flat slope in a straight alignment. The cross section of the main beam is a single-box double-chamber contour cross-section prestressed concrete box girder. The tower features a diamond-shaped structure with an inverted Y-shape above the deck and a contracted diamond shape below the deck. Figure 2a–c illustrates the main bridge and the cable-stayed bridge bearings.

The semi-floating system of the main bridge includes vertical restraints at the connecting and auxiliary piers, as well as horizontal restraints and longitudinal movement on the upstream side. Vertical and transverse restraints are applied between the pylons and the main beams. The main beam has a single-box double-chamber cross-section, with a total width of 13 m and a beam height of 4.0 m at the center. The width-to-span and height-to-span ratios are 1/23.08 and 1/75, respectively. The tower’s height from the bottom is 118 m (112.5 m for the smaller span), with an inverted Y-shape above the deck and a shrunk diamond shape below. The tower height above the deck is 75 m, and the ratio of the tower’s height at the top of the beam to the main span is 1/4.0. The longitudinal width of the tower expands from 6.5 m at the top to 8 m at the bottom.

The cable-stayed system uses galvanized parallel steel wire cables with a tensile standard strength of 1860 MPa. The cables are arranged in a fan-shaped configuration with a spaced double cable surface system. The bridge comprises 72 pairs of cable-stayed cables, with the tension end located within the tower. Cable spacing varies: 8 m in the main span, 8 m near the tower in the side span, and 4 m in the end span.

The auxiliary and connecting piers are solid piers with rounded ends, supported by bored pile foundations. The pile diameter is φ2.0 m for the small mileage auxiliary pier and connecting pier, and φ1.5 m for the large mileage. The dimensions of the two tower caps are 21.6 m (length) × 21.6 m (width) × 5 m (thickness), with a wedge-shaped base of 2.5 m in height. The group pile foundation consists of 16 bored piles with a diameter of 2.8 m. The length of the cable tower pile is 73 m on the small mileage side and 55 m on the large mileage side.

The ground motion input

Seismic motion parameters

Due to limited geological exploration data, this study assumes the presence of a significant fault in the area, with an approximate fault length of 150 km and a dip angle ranging from 40° to 60°. This fault is characterized as a normal fault. Based on the seismic risk assessment, the maximum potential earthquake magnitude is estimated to be 7.0, with the epicenter located at 20 km. The semi-empirical relationships and standard deviations used to estimate the global source parameters, along with the mean estimates of these parameters, are provided in Table 1. Table 2 lists other relevant source parameters for the site. The results of the exploration of the aforementioned active fault indicate that the control length of the rupture for a magnitude 7.0 earthquake is 120 km. Considering the burial depth of the earth’s crust’s low-velocity layer, the rupture surface width is limited to 30 km.

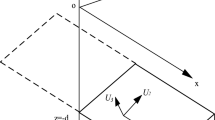

Ground motion component conversion crossing fault angles

When a bridge structure crosses an active fault, the crossing angle can significantly influence its seismic response. The fault rupture angle is unpredictable during an earthquake; thus, this study considers the fault crossing angle as a basic variable. The impact of the fault crossing angle on the seismic response characteristics of the bridge structure in both longitudinal and transverse directions is examined. According to Eq. (22), the directional effect ground motion and slip effect ground motion are converted into longitudinal bridge-oriented ground motion and transverse bridge-oriented ground motion to input the displacement.

Where ed is the fault slip direction coefficient. Because the ground motion on the left and right sides of the strike-slip fault exhibits opposite behaviors, the slip direction coefficient is taken as 1 on the left side of the fault and − 1 on the right side. Using Eq. (22), the longitudinal and transverse components of ground motion at various crossing angles can be obtained.

Based on the seismic source parameters of the long-span railway cable-stayed bridge provided in Tables 1 and 2, and using the basic theory of mixed simulation of the ground motion field across the fault, the ground motion input for the 300-meter span railway cable-stayed bridge with strike-slip and dip-slip faults is obtained through the superposition of high and low frequencies, as shown in Fig. 3a–d.

The seismic motions applied to the supports on both sides of the fault for the transverse fault bridge are illustrated in Fig. 4. Two sets of ground motion time histories, representing the seismic motions in two directions, are applied at the base of four piers and two towers. For the direction perpendicular to the fault (FN), ground motions of the same magnitude and direction are applied on both sides of the fault using a consistent excitation method. For the direction parallel to the fault (FP), ground motions of the same magnitude but with opposite directions are applied on both sides of the fault using a non-consistent excitation method.

Nonlinear finite element model of cable-stayed bridge

Piers and towers, as vulnerable components of cable-stayed bridges during earthquakes, are prone to plastic failure. Therefore, the nonlinear fiber beam-column elements from the OpenSees (Version 3.6.0). element library are used for simulation. The fiber sections, based on the reinforcement details, are divided into core area concrete, protective layer concrete, and steel bars, each assigned a corresponding material model. The Hardening material model from OpenSees (Version 3.6.0) simulates the bilinear ideal elastoplastic behavior.

To accommodate the anisotropic characteristics of materials, the ZeroLengthelement is employed, allowing for easy modification of material properties in each degree of freedom. This element is also flexible and convenient to use.

The main beam, which remains mostly elastic during an earthquake, is simulated using elastic beam elements. These elements’ cross-sectional characteristics, including area, moment of inertia, and elastic modulus, are calculated based on the material properties and dimensions of the structure. Additionally, the simulation considers the influence of secondary loads, such as bridge deck pavement.

The MinMax material in OpenSees is used to model the automatic deactivation of cable elements when stress thresholds are reached. Initial Strain Material is nested within to apply the initial strain of the cables. The cables themselves are simulated using the Truss Element. Table 3 lists the materials and elements used in simulating the primary components, such as piers, pylons, bearings, main beams, and cables. In seismic design, a conservative design method is usually adopted to ensure the safety of the structure. Generally speaking, after considering the pile-soil effect, the pile foundation will dissipate part of the energy of the earthquake, thus providing a certain degree of protection for components such as the pylon and piers of the cable-stayed bridge. In order to ascertain the seismic response of components such as bridge towers, bridge piers, and bearings under the action of strike-slip faults, this study considers from an unfavorable perspective and in order to highlight the research focus, the influence of pile-soil effect is not considered.

A nonlinear numerical model was established based on the OpenSees (Version 3.6.0) finite element platform, as shown in Fig. 5, considering the principles of element type and material property selection. It is important to note the following: (1) The model does not account for pile-soil interaction effects on the seismic response. Consequently, the base of the bridge tower and pier is consolidated in the finite element model. (2) The analysis focuses on the nonlinearity of structural materials while excluding the geometric nonlinearity of cable-stayed bridges from the modeling.

Seismic response analysis of cable-stayed bridges across faults

Seismic response analysis of cable-stayed bridge

The seismic response of bridge pier

To comprehensively analyze the seismic response of key structural components when the main span of a long-span cable-stayed bridge crosses an active fault at various angles, the representative displacement of Pier No. 1 along its height range of -35 m to 0 m in both the longitudinal and transverse directions is illustrated in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. The figures show that the displacement of the pier in both directions remains relatively consistent along the height under different spanning angles, with minimal changes observed. However, the displacement along the bridge direction is significantly smaller within the spanning angle range of 60° to 120°, while it is larger when the spanning angle is near 0° or 180°, reaching a maximum displacement of approximately 1.75 m. In contrast, the transverse displacement follows an opposite trend, with smaller displacements near 0° and 180°, and the largest lateral displacement of over 1.70 m occurring at a spanning angle of 90°. These results indicate that under cross-fault seismic waves, the pier experiences uniform vertical and horizontal translation, with negligible displacement variation along its height.

The corresponding shear force, bending moment, and curvature response of Pier No. 1 along its height range of -35 m to 0 m in the bridge and transverse directions are shown in Fig. 6c to h. The internal force response increases from the top of the pier downward, with the bottom section experiencing significantly greater forces than other sections. Comparing the internal force response under different spanning angles reveals that the maximum internal forces along the bridge direction occur within the spanning angle range of 60° to 120°, with the maximum bending moment close to 2.5 × 10^8 \(kN \cdot m\) and the maximum curvature response reaching 3.0 × 10^-4. Conversely, at spanning angles near 0° or 180°, the internal force response along the bridge is minimal. For the transverse direction, the maximum bending moment and curvature response occur near 0° and 180°, while the minimum values are observed at 90°. The internal force and displacement responses show opposite trends in both longitudinal and transverse directions.

To further analyze the elastoplastic behavior of each pier under cross-fault ground motion, the bending moment-curvature relationship curves (hysteresis curves) for the longitudinal and transverse directions of the bottom sections of Piers No. 1 to 4 are shown in Fig. 7a–h. The hysteretic curves reveal different patterns for each pier. Specifically, the bottom sections of Piers 1 and 2 exhibit relatively full hysteresis loops in both longitudinal and transverse directions, indicating significant energy dissipation and plastic deformation. In contrast, the hysteresis curves of Piers 3 and 4 are slender, showing minimal energy dissipation and suggesting that these piers remain within the elastic range. The disparity in the moment-curvature response between the left and right piers may be attributed to the inconsistency in ground motion input across the fault.

The seismic response of the tower

To further analyze the seismic response of the pylons at different span angles, Fig. 8a–h illustrates the variation of the peak seismic response of the left tower with height in both the longitudinal and transverse directions.

Figure 8a and b show that the longitudinal and transverse displacements of the pylon significantly increase with height, similar to the seismic response of the pier. The longitudinal displacement is smallest at a spanning angle of approximately 90° and largest at angles near 0° or 180°. Conversely, the lateral displacement exhibits the opposite trend, with minimal displacement near 0° and 180° and maximum displacement around 90°.

Regarding internal force response, the longitudinal and transverse shear force, bending moment, and curvature response of the left tower decrease with increasing height. The bottom section of the pylon experiences the highest internal forces. However, abrupt changes in internal force response occur at elevations of -6 m and 35.63 m due to the limiting effect of the beam at these positions and the transverse interaction between the beam and the pylon body. Notably, the peak shear response at the beam connection exceeds that at the pylon base, indicating a critical cross-section requiring attention in seismic design.

To further evaluate the elastoplastic behavior of the bridge pylon’s bottom section, Figs. 9a and b and 10a and b present the longitudinal and transverse moment-curvature curves of the left and right base sections. The longitudinal hysteresis loops of the bottom sections of both towers are relatively full, indicating significant energy dissipation, whereas the transverse hysteresis loops are more irregular due to the differing ground motion input modes. The longitudinal part primarily reflects the fault rupture effect, while the transverse part reflects the fault slip effect. Additionally, Figs. 9 and 10 reveal that the negative longitudinal curvature of the pylon’s bottom section is larger than the positive curvature, lacking symmetry, which is related to the ground motion input and the stress state of the pylon components.

The influence of seismic amplitude adjustment on the structural response

To further investigate the effect of trans-fault ground motion amplitude on the seismic response of long-span cable-stayed bridges, an amplitude adjustment factor (β) is introduced into the input ground motion time history. This adjustment factor controls the waveform parameters of the ground motion time history, with β ranging from 0.5 to 2 in intervals of 0.2. Figures 11 and 12 present the seismic response of the bridge structure across the fault, controlled by the spanning angle and the ground motion amplitude adjustment factor.

Figures 11a and b and 12a and b indicate that both fault angles and amplitude adjustment coefficients significantly impact the peak displacement of the supports (β). The displacement response of the supports increases notably with higher adjustment factors, both longitudinally and transversely. When the fault spanning angle is between 80° and 120°, the longitudinal displacement response of the supports is at its maximum, while the lateral displacement response is at its minimum, showing an inverse relationship. Comparing the displacement responses of bearings No. 1 and No. 2, the No. 2 bearing exhibits greater displacement than No. 1 under the same spanning angle and adjustment factor, indicating that displacement response increases with proximity to the fault. The three-dimensional displacement response surface shows a symmetrical trend at the 90-degree spanning angle.

Figure 13a–f demonstrates that different fault angles and amplitude adjustment coefficients (β) significantly affect the peak seismic response of pier No. 1. With an increasing adjustment factor, the pier’s shear force, bending moment, and curvature also increase. The longitudinal shear force, bending moment, and curvature of the pier initially increase and then decrease with an increasing fault spanning angle, peaking between 80° and 120°, and reaching a minimum at 0° and 180°. Conversely, the transverse shear force, bending moment, and curvature of the pier decrease initially and then increase with the fault spanning angle, with the minimum response between 80° and 120°, and the maximum at 0° and 180°. The three-dimensional response surfaces for shear force, bending moment, and curvature exhibit symmetrical trends at a 90-degree spanning angle, with longitudinal and transverse responses showing opposite variation patterns.

Furthermore, the influence of different fault spanning angles and amplitude adjustment coefficients β on the peak.

Similarly, Fig. 14a–h shows the influence of different fault spanning angles and amplitude adjustment coefficients (β) on the peak seismic response of the tower. The shear force, bending moment, and curvature of the bridge pylon also increase gradually with a higher ground motion amplitude adjustment coefficient. The longitudinal shear force, bending moment, and curvature of the pylon increase initially and then decrease with the fault crossing angle, reaching maximum values between 80° and 120°, and minimum values at 0° and 180°. The transverse responses follow an inverse trend, with minimum values between 80° and 120°, and maximum at 0° and 180°. The three-dimensional surfaces of the internal force and curvature responses of the bridge pylon show symmetrical variation patterns at the 90-degree spanning angle.

Conclusion

This paper investigates the artificial synthesis of ground motion in strike-slip fault zones and the subsequent seismic response of long-span railway cable-stayed bridges. The goal is to provide guidance for seismic design in near-field areas affected by trans-faults. The study develops a method to simulate ground motions across faults, incorporating both high and low frequencies using finite fault and equivalent velocity pulse models. The analysis focuses on the effects of fault spanning angle, support displacement, and amplitude adjustment coefficient on the seismic response of the bridges. The key findings are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A hybrid simulation technique has been developed for strike-slip faults, combining high and low frequencies through finite fault and equivalent velocity pulse models. This method ensures consistent total durations for ground motions at both frequency ranges and uniform load sub-step times. The time history of trans-fault seismic waves is superimposed across the entire time domain. The effectiveness and accuracy of this method in capturing rupture directionality and slip effects have been validated, providing a novel approach for simulating ground motions in fault-crossing bridges.

-

2.

The fault crossing angle significantly affects the seismic response of long-span railway cable-stayed bridges. Longitudinal shear forces and bending moments at the base of the pier peak within the 80° to 100° range, with minimal responses observed at 0° or 180°. Conversely, transverse shear forces and bending moments exhibit an inverse pattern. The hysteresis loops for piers 1 and 2 indicate substantial energy dissipation and plastic deformation, whereas piers 3 and 4 display slender hysteresis curves with minimal energy dissipation and deformation. Discrepancies in bending curvature responses between left and right piers are attributed to inconsistencies.

-

3.

The longitudinal and transverse displacements of the tower increase significantly with height. The smallest longitudinal displacement occurs near a spanning angle of 90°, while the largest is at approximately 0° or 180°. Abrupt changes in internal force responses at elevations 6 m and 35.63 m are due to beam constraints and transverse interactions between the beam and the pylon. The shear response at the beam connection exceeds that at the bottom of the bridge pylon, highlighting this position as critical in seismic design. Longitudinal hysteresis loops are fuller compared to the more chaotic transverse loops, reflecting the influence of different ground motion input modes.

-

4.

The displacement response of bearing No. 2 is greater than that of bearing No. 1 under identical spanning angles and adjustment factors, indicating larger responses closer to the fault. Three-dimensional displacement response surfaces show symmetrical trends at a 90-degree spanning angle. As the amplitude adjustment coefficient increases, shear forces, bending moments, and curvatures for both piers and towers rise. Longitudinal shear force, bending moment, and curvature of the pylon initially increase and then decrease with the fault crossing angle, peaking between 80° and 120° and minimizing at 0° and 180°. Conversely, transverse shear forces, bending moments, and curvatures exhibit an opposite pattern. The three-dimensional surfaces for these responses show symmetrical variations at a 90-degree spanning angle.

Future research should aim to simulate the entire collapse process of bridges under near-fault ground motions to understand the failure sequence of different components. This will be crucial for disaster prevention and mitigation. Suggested future research directions include:

-

1.

Full-Process Simulation: Conduct comprehensive simulations of near-fault bridge behavior to identify the sequence of damage to structural components under seismic loading. This will enhance disaster prevention and mitigation capabilities for bridges in the western regions of China.

-

2.

Post-Earthquake Analysis: Utilize the near-fault ground motion synthesis method proposed in this study to analyze post-earthquake conditions of complex mountainous bridges. Particular attention should be given to the impact of near-fault pulses on landslides, rockfalls, and other natural hazards affecting bridge structures.

-

3.

Vulnerability and Reliability Analysis: Perform vulnerability analysis and reliability studies of long-span bridges under near-fault seismic effects. This will provide critical insights for improving future bridge designs and seismic mitigation measures.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Avar, B. B. & Hudyma, N. W. Earthquake surface rupture: a brief survey on interdisciplinary research and practice from geology to geotechnical engineering. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(12), 5259–5281 (2019).

Bazarchi, E., Saberi, R. & Alinejad, M. Seismic hazard assessment of Tehran, Iran with emphasis on near-fault rupture directivity effects. Earthq. Sci. 31(1), 1–11 (2018).

Tochaei, E. N., Taylor, T. & Ansari, F. Effects of near-field ground motions and soil-structure interaction on dynamic response of a cable-stayed bridge. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 133, 106115 (2020).

Li, S. Q. & Liu, H. B. Comparison of vulnerabilities in typical bridges using macro seismic intensity scales. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01094 (2022).

Yang, S., & Mavroeidis, G. P. Bridges crossing fault rupture zones: A review. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engg. 113, 545–571 (2018).

Zhang, D., Sun, Z. & Fang, Q. Scientific problems and research proposals for Sichuan–Tibet railway tunnel construction. Undergr. Space. 7(3), 419–439 (2022).

Cui, P., & Jia, Y. Mountain hazards in the Tibetan Plateau: research status and prospects. National Sci. Review2(4), 397–399 (2015).

Cui, Peng, et al. "Scientific challenges in disaster risk reduction for the Sichuan–Tibet Railway." Engg. Geo. 309, 106837 (2022).

Park, S. W. et al. Simulation of the seismic performance of the Bolu Viaduct subjected to near-fault ground motions. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 33(13), 1249–1270 (2004).

Ucak, Alper, George P. Mavroeidis, and Panos Tsopelas. "Behavior of a seismically isolated bridge crossing a fault rupture zone." Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 57: 164-178 (2014).

Goel R K, Chopra A K. Nonlinear analysis of ordinary bridges crossing fault-rupture zones. J. Bridge Engg. 14(3), 216–224 (2009).

Goel R, Qu. B. et al. Validation of fault rupture-response spectrum analysis method for curved bridges crossing strike-slip fault rupture zones. J. Bridge Eng. 19(5), 06014002 (2014).

Saidim, S. et al. Shake table studies and analysis of a two-span rc bridge model subjected to a fault rupture. J. Bridge Eng. 19(8), 182–190 ( 2014).

Yi, J., Yang, H. & Li, J. Experimental and numerical study on isolated simply-supported bridges subjected to a fault rupture. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 127, 105819 (2019).

Hui, Y., Wang, K., & Li, C. Study of Seismic Design for Bridges Crossing Fault-Rupture Zones. In CICTP 2014: Safe, Smart, and Sustainable Multimodal Transportation Systems, 1061–1068 (2014).

Hui, Y., Zhou, T., Liu, J., Jia, H., Zhang, S. Seismic response study of multi-span continuous beam bridges near faults considering permanent displacement attenuation effects. Structures 69, 107516 (2020).

Hui, Y., Fan, L., Lv, J., Li, J., & Jia, H. Influence of velocity pulse directivity on seismic response of cross-fault bridges. Structures 69, 107546 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Seismic response of high-speed railway simple-supported girder track-bridge system considering spatial effect at near-fault region. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 158, 107283 (2022).

Jia, Hongyu, et al. Track-bridge deformation relation and interaction of long-span railway suspension bridges subject to strike-slip faulting. Eng. Struct. 300, 117216 (2024).

Zeng, C., Jiang, H., Song, G., Ren, Y. & Xue, Z. Nonlinear seismic responses of a long-span railway suspension bridge crossing strike-slip fault rupture zones. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 177, 108388 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. A new baseline correction method for near-fault strong-motion records based on the target final displacement. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 114, 27–37 (2018).

Jia, H. et al. A review of seismic research on cross-fault bridges. J. Southwest. Jiaotong Univ. 35–43 (2020). (In Chinese).

Hartzell, S. H. Earthquake aftershocks as Green’s functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 5(1), 1–4 (1978).

Boore, D. M. Stochastic Simulation of high-frequency ground motions based on seismological models of the Radiated Spectra. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 73(6A), 1865–1894 (1983).

Silva, W. J. et al. A methodology to estimate design response spectra in the near-source region of large earthquakes using the band-limited-white-noise ground motion model[A].Palm Springs. California. 1, 487–494 (1990).

Beresnev, I. A. & Atkinson, G. M. Modeling finite-fault radiation from the ω n spectrum. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 87 (1), 67–84 (1997).

Beresnev, I. A. & Atkinson, G. M. FINSIM–a FORTRAN program for simulating stochastic acceleration time histories from finite faults. Seismol. Res. Lett. 69(1), 27–32 (1998).

Assatourians, K. & Atkinson, G. EXSIM12: A Stochastic Finite-Fault Computer Program in FORTRAN (2012).

Makris, N. & Chang, S. P. Effect of viscous, viscoplastic and friction damping on the response of seismic isolated structures. Earthquake Eng. Struct. Dynam. 29, 85–107 (2000).

Castro, R. et al. Near‐source attenuation and spatial variability of the spectral decay parameter kappa in central Italy. Seismol. Soc. Am. 93(4), 2299–2310 (2022).

Wells, D. L. & Coppersmith, K. J. New empirical relationships among magnitude, rupture length, rupture width, rupture area, and surface displacement. Bull. Seismol. Somety of Am. 84(4), 974–1002. (1994).

Ji, C. & Archuleta, R. J. Two empirical double-corner‐frequency source spectra and their physical implications. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 111(2), 737–761 (2021).

Hanks, T. C. & McGuire, R. K. Stochastic Point Source Modeling of Ground Motion in the Cascadia Region. Seismol. Res. Lett. 68(1), 74–85 (1997).

Atkinson, G. M. & Mereu, R. F. The shape of ground motion attenuation curves in southeastern Canada. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 82(5), 2014–2031 (1992).

Zhang, C. Lu, J. B., Jia, H. Y., Lai, Z. C., Li, X., & Wang, P. G. Influence of near-fault ground motion characteristics on the seismic response of cable-stayed bridges. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 18, 6375-6403 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52008047), and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2024NSFSC0932). Their supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Jin Zhang, Ke-jian Chen, Yu-feng Gao. Funding acquisition: Jin Zhang. Investigation: Jin Zhang, Xiang Liu, Ya-ting Cao, Heng Guo. Formal analysis: Xiang Liu, Ya-ting Cao, Heng Guo. Writing—original draft: Jin Zhang, Xiang Liu, Ya-ting Cao, Heng Guo. Writing—review & editing: Jin Zhang, Ya-ting Cao.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Liu, X., Cao, Yt. et al. Nonlinear seismic response analysis of long-span railway cable-stayed bridges crossing strike-slip faults. Sci Rep 14, 25479 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77135-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77135-w